Abstract

Background

Despite recognized benefits, many children with cystic fibrosis (CF) do not consistently participate in physical activities. There is little empirical literature regarding the feelings and attitudes of children with CF toward exercise programs, parental roles in exercise, or factors influencing exercise experiences during research participation.

Objectives

To describe the exercise experiences of children with CF and their parents during participation in a six-month program of self-regulated, home-based exercise.

Methods

This qualitative descriptive study nested within a randomized controlled trial of a self-regulated, home-based exercise program used serial semi-structured interviews conducted individually at two and six months with 11 purposively selected children with CF and their parent(s).

Results

Six boys and five girls, ages 10–16, and parents (nine mothers, four fathers) participated in a total of 44 interviews. Five major thematic categories describing child and parent perceptions and experience of the bicycle exercise program were identified in the transcripts: (a) motivators; (b) barriers; (c) effort/work; (d) exercise routine; (e) sustaining exercise. Research participation, parent-family participation, health benefits, and the child’s personality traits were primary motivators. Competing activities, priorities and responsibilities were the major barriers to implementing the exercise program as prescribed. Motivation waned and the novelty wore off for several (approximately half) parent-child dyads, who planned to decrease or stop the exercise program after the study ended.

Discussion

We identified motivators and barriers to a self-regulated, home-based exercise program for children with CF that can be addressed in planning future exercise interventions to maximize the health benefits for children with CF and the feasibility and acceptability to the children and their families.

Keywords: Exercise, children, cystic fibrosis, chronic disease, qualitative research

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is the most common profoundly life-shortening autosomal recessive disorder among Caucasians, occurring in 1 of every 2,500 live White births, and affecting approximately 80,000 individuals worldwide (Cohen-Cymberknoh, Shoseyov, & Kerem, 2011). Today with early diagnosis, comprehensive care provided through specialized CF treatment centers, and improvements in drug, nutritional, and physio-therapies, the median predicted age of survival has increased to 38 years (Cystic Fibrosis Foundation, 2010). Children diagnosed with CF are advised to follow a daily regimen that includes techniques designed to enhance secretion clearance, reduce airway inflammation, and prevent recurrent infections (Cohen-Cymberknoh et al., 2011; Mogayzel et al., 2013). Within the past two decades, exercise has been added to the complement of recommended treatments for CF (Dwyer, Elkins, & Bye, 2011; Higgins et al., 2013). Exercise can be both physiologically and psychologically advantageous with specific benefits that relate to lung health, including enhanced sputum clearance (Cholewa & Paolone, 2012), reduced breathlessness (Moorcroft, Dodd, Morris, & Webb, 2004), preserved and possibly improved lung function (Paranjape et al., 2012), and possibly even lower mortality (van de Weert-van Leuuwen et al., 2012).

Despite the well-recognized benefits of exercise, many children with CF do not consistently participate in physical activities and are not as active as their healthy peers (Nixon, Orenstein, & Kelsey, 2001). Potential reasons include the time burden required to carry out prescribed therapy, disease progression which compromises lung function, and lack of parental involvement as motivators and role models (Moola, Faulkner, & Schneiderman, 2012; Rand & Prasad, 2012). Participation in a structured program of exercise has been shown to improve lung function and self-reported exercise habits in children with CF (Gruber, Orenstein, &Braumann, 2011; Orenstein et al., 2004; Paranjape et al., 2012), with the greatest improvement seen in those least fit. Sharing this information has been suggested as a means to motivate improved exercise adherence (Rand & Prasad, 2012).

Although exercise outcomes of training interventions (Orenstein et al., 2004; Paranjape et al., 2012; Schneiderman-Walker et al., 2000; Selvadurai et al., 2002) and children’s attitudes about physical activity have been studied (Gruber et al., 2011; Moola et al., 2012; Smith, Modi, Quittner, & Wood, 2010; Swisher & Erickson, 2008), there has been limited exploration of how introduction of an exercise recommendation may impact other aspects of the CF regimen. Exercise regimens tested in a research protocol that enroll children typically require parental supervision and monitoring. CF patients’ feelings and attitudes about research participation, parental roles, and factors influencing the experience, including facilitators, barriers, and developmental issues, remain largely unexplored.

Additions to the treatment regimen must be carefully considered and balanced in terms of burden and benefit. To help with the management of the daily burden of CF treatment routines and promote adherence with exercise as part of standard therapy, the experience needs to be better understood. This paper describes the exercise experiences of children with CF and their parents during participation in a randomized, controlled trial that examined the effects of a six-month program of self-regulated, home-based exercise in addition to standard care provided by the CF Center.

Methods

Design

A qualitative descriptive study was nested within the primary experimental framework using a concurrent mixed methods approach (Creswell & Plano Clark, 2007) to explore the experiences of the children and parents with the exercise regimen. The study was approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board. All participants provided informed consent (parents) or assent (children).

The self-regulated exercise program consisted of an at-home bicycle exercise regimen performed three times a week for six months on an electronically braked exercise bike supplied by the study. Exercise intensity was self-regulated using the Children’s OMNI Scale (Higgins et al., 2013; Robertson et al., 2000). Two exercise routines were performed on the bicycle in an alternating sequence during each session. One intensity was lower, corresponding to activities undertaken during free play, and the second higher, corresponding to metabolic rates to enhance aerobic fitness. Children were called weekly for the first six months of the study. Children were then instructed to maintain their self-regulated exercise activity for the remaining six months of the study without reinforcement (weekly phone calls). The attention control group received weekly telephone calls for six months with no mention of exercise. After six months, they received the exercise bike and participated in the same self-regulated exercise program. Participants received monetary compensation for attending five test sessions required by the study. Total compensation was $100 per child and $150 per parent.

Sample

Child-parent pairs were purposively selected to participate in interviews for variation in group assignment, age, gender, and severity of illness as measured by the pulmonary function testing parameter forced expired volume in one second (FEV1), peak oxygen consumption (VO2) measured on a maximum exercise test, and health related quality of life. The possibility of selection for participation in interviews was included in the consent for the primary study. Those selected were notified by the project coordinator for the primary study (LWH) and asked to reconfirm their consent. Sampling continued until no new themes or patterns were detected in the parent and child narratives. Recurrent patterning became evident in the data by the seventh dyad, saturation was achieved by the eleventh dyad, and enrollment of additional parent-child dyads ceased.

Data Collection

Individual child and parent interviews, conducted at two months into the exercise program and again at six months, were arranged in conjunction with scheduled clinic visits. The interviews were conducted by a single researcher (LAH) beginning with a grand tour question (“Tell me about your experience with the exercise program?” [parents] or “Tell me about your exercise routine?” [children]), using a flexible approach (Deatrick & Ledlie, 2000), and an open-ended semistructured interview guide (Table 1). Probes were added during the ongoing data analysis and, in some cases, individualized to follow-up on previous themes or problems identified in the first interview set for a parent-child dyad. About halfway through data collection, we discovered that the “novelty (of the exercise bike) wore off” for some dyads. During subsequent interviews, we asked participants’ opinions about continuing the bicycle exercise program after the study ended. Interviews took place in the pediatric pulmonary clinic. Interviews, ranging from 7 to 30 minutes in length, were audio recorded and professionally transcribed.

Table 1.

Interview Guide

| Interviewee | Question |

|---|---|

| Parent | Tell me about your experience with the self-regulated exercise program? |

| What was your child’s exercise routine before starting the program? (only ask at two-month time point) Describe your child’s exercise routine now? | |

| What do you like/dislike about the self-regulated exercise program? | |

| What would you say is the most difficult part about the self-regulated exercise program? | |

| What things help your child to exercise or get started with exercise? | |

| In what ways have you been involved with your child’s exercise program? | |

| How has the exercise program affected the daily management of your child’s CF? | |

| How often do you think your child will exercise with the bike after the study ends? | |

| Child | Tell me about your exercise routine before starting the new program? (only ask at two-month time point). Tell me about your exercise routine now? |

| Tell me more about what the self-regulated exercise program is like for you? (or) What do you think about the new (self-regulated) exercise program? | |

| How does your body feel when you first start exercising? in the middle? at the end of exercising? | |

| What do you like about the self-regulated exercise program? | |

| What would you say is the hardest part of this exercise program? | |

| What helps you to exercise or get started? | |

| In what ways has your mom/dad been involved in the exercise program? | |

| How has the self-regulated exercise program changed your daily care routine for your CF? | |

| How often do you think you will exercise with the bike after the study ends? |

Data Analysis

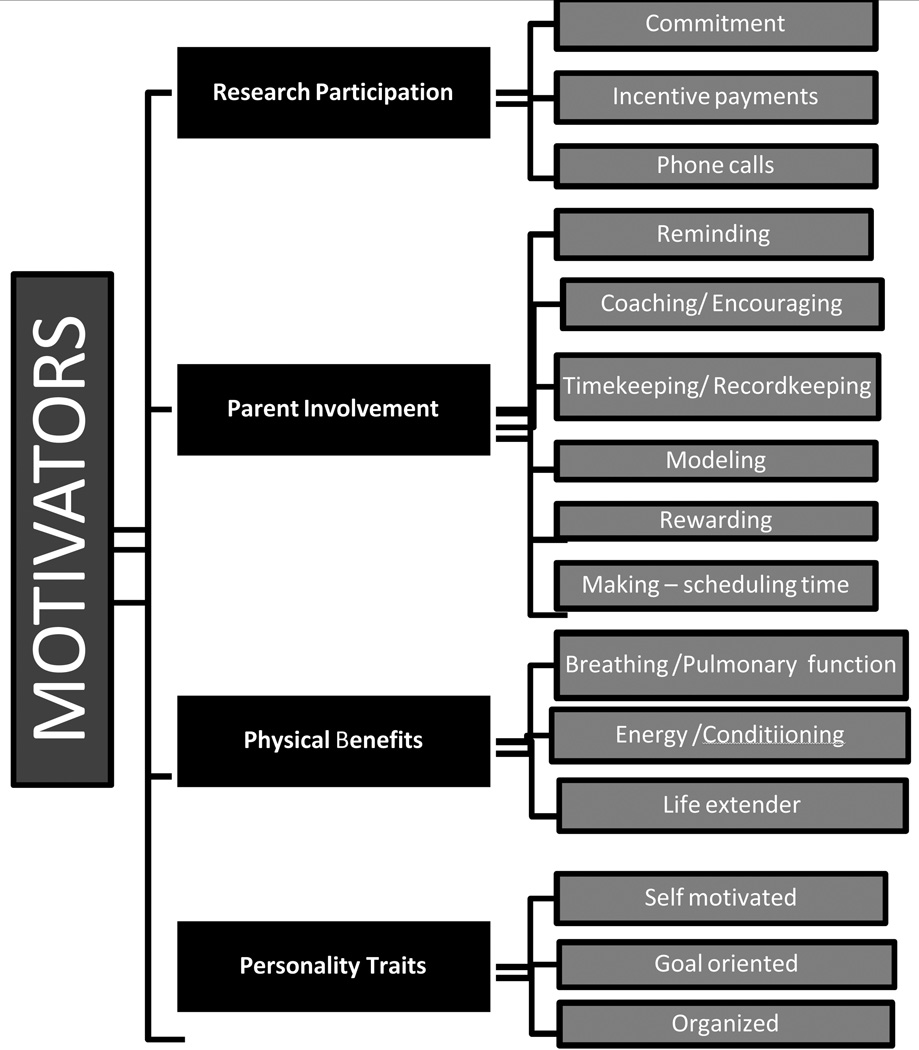

Initial coding involved line by line review and labeling of phrases or sentences in the interview text describing the child or parent experience and/or perceptions of the exercise program (Graneheim & Lundman, 2004). A preliminary code list and definitions were developed by an investigator experienced in qualitative analysis (MBH) and reviewed and edited with the interviewer (LAH) and other members of the team. Codes were grouped into categories and subcategories. Categories and category definitions were constructed using low level inference; that is, close to the participants’ words (Sandelowski, 2000). The categories, subcategories, and definitions were revised by the investigator team for most accurate representation, parsimony, and fit after review of four exemplar transcripts. Specifically, “motivators” and “barriers” were elevated to categories which provided a more conceptually coherent organization of the data and analysis. Figure 1 illustrates the ‘motivators’ thematic category derivation with subcategories and the dimensional codes that comprised each subcategory. Matrices were constructed to delineate main categories and subcategories by case, type of participant (parent or child), and time point (first or second interview) to examine thematic strength and depth across time and participants. Additional matrix iterations included child characteristics, specifically age and gender, to explore potential patterns of response (Miles & Huberman, 1994).

Figure 1.

Illustration of the “motivators” thematic category derivation with subcategories and the dimensional codes comprising each subcategory.

Trustworthiness

To assure credibility and consistency, audio was recorded and practice interviews were critiqued, and this procedure was continued throughout the study, interviewing parents and children separately. Maximum variation sampling also strengthens credibility of the study. Although member checks were not conducted in this low-inference content analysis, agreement among coresearchers was achieved in the analysis and categorization of data (Graneheim & Lundman, 2004). Additionally, matrices and the stem-leaf plot (Figure 1) confirm that categories and subcategories were fully represented across cases and participants. An audit trail of all analytic and methodological decisions was also maintained. The use of multiple data sources (parents and children) and multiple interviews across a four-month time period (prolonged engagement) strengthens dependability.

Results

Eleven child-parent pairs participated in the study. Six children were from the experimental group, and five from the attention-control group (five girls, six boys; ages 10–16 years, M = 12.6 years). Parent interview participants were nine mothers and four fathers, ages 29–51 years (parental partners changed in two cases in which mothers accompanied the child to the second research appointment). All participants were Caucasian. None of the children or parents approached refused to participate in interviews. All 11 child-parent pairs were interviewed twice (two months and six months after receiving the exercise bike). A total of 44 interviews were conducted between January 2008, and November 2009.

Five major categories describing child and parent perceptions and experience of the bicycle exercise program were identified in the transcripts: (a) motivators; (b) barriers; (c) effort/work; (d) exercise routine; (e) sustaining bicycle exercise. Table 2 illustrates the number of participants (parent and child) represented in the coding of the exemplar themes and subthemes. Matrix analysis revealed no particular patterns or differences with regard to age or gender among the main categories identified. Reportable problem areas, dangers, or complaints with the exercise intervention were not detected.

Table 2.

Strength and Source of Selected Categories, Subcategories, and Codes

| Child | Parent | CATEGORY/Subcategory /Code |

|---|---|---|

| MOTIVATORS | ||

| ••••• | •••••••••• | Research Participation |

| Physical Benefits | ||

| ••••••• | ••••• | General Health |

| •••••• | •••••••• | Pulmonary function/ Breathing |

| •••••••••• | ••• | Energy |

| •• | Life Extender | |

| Personality Traits | ||

| •• | •••••• | Self-motivated |

| •• | Organized | |

| •• | • | Goal-oriented |

| ••••••• | ••••••••• | Parent Involvement |

| BARRIERS | ||

| •••••• | •••••••• | Time and Competing Tasks/ Activities |

| •••• | ••••••••• | Seasonal Activity |

| •••••• | • | Work/Tired |

| EFFORT/WORK | ||

| •• | • | Chore |

| ••••• | • | Difficult |

| ••••••••••• | •••• | Effort/work |

| •• | Push | |

| EXERCISE ROUTINEa | ||

| •••• | ••••• | Fitting into routine |

| •••••••••• | ••••••••• | Exercise as part of CF routine |

| ••••••••••• | •••••••••• | Exercise routine |

| ••••••• | •••••• | Sports |

| SUSTAINABILITY OF BIKE EXERCISEb | ||

| •••• | •• | Plans to sustain bike exercise program |

| ••• | •••• | Anticipates reduced use/adherence to bike exercise |

Note: Only one • is allocated per source regardless of number of times the code may appear in interviews.

An interview question specifically asked about the child’s typical exercise routine.

One child shifted from planning to sustain (time 1) to anticipating reduced adherence (time 2); only one child-parent dyad differed with the child planning to sustain and the parent anticipating reduced use/adherence to the program.

Motivators

Strategies that encouraged or inspired children to perform the bicycle exercise and adhere to the prescribed exercise program as “motivators” were categorized. See Figure 1.

Research participation

Parents and children described their research commitment and participation as a motivator. “‥it helps me get him to do it just because we are in the study. It is hard for me to make him exercise just because I don’t, I guess” [parent]:

…but I’m excited that she is taking part in it and I’m trying to really, you know, teach her that (she) should be excited for the same reason, that she is really trying to help the doctors with better ways to treat the disease and everything. [parent]

A mother and her 10-year-old daughter both framed research participation as “giving back” “helping the team (MDs, etc),” and “helping other kids with CF.” Their ongoing participation in and adherence to the exercise program was framed as a family value for “finishing what you started” and “your commitments.”

Some children cited the payment for participation as their incentive to complete the exercise program. The exercise bicycle which children kept during and after study participation was also perceived as a reward and motivator for the exercise program. Children and parents both identified the phone calls from research staff as a motivating force and related not carrying out the exercises as often when calls stopped (after six months).

Parent-family involvement

In general, parent and sibling (family) involvement with or influence on the bicycle exercise program was a positive motivator. Most parents and children saw acquiring the bike, which other family members occasionally used, as a benefit or bonus of study participation. “I like that you got your own exercise bike and that you can work at home too and for the whole family to use it” [child]:

When it (bike) first came in it was like we were kind of fighting (over) who would get on the bike first kind of deal. And then it was mainly. [child] He is the one who uses it the most. But I’ll try to sneak on every once in a while. [mother]

Parents acted as motivators and facilitators of the exercise program by reminding, coaching/encouraging, timekeeping, modeling the exercise, record keeping, rewarding, and by “making the time” in the family schedule for the child to exercise:

I tell him to go out and do it….I do the timing, the timer, and tell him you know, “go up to four or down to four and up to seven” (referring to numbers on the OMNI Scale). [mother]

The following child’s interview quotation confirmed the essential role his mother played as a motivator and coach/teacher for the exercise program. “I don’t know if my mom wasn’t there and I had to do it myself, that would be kind of hard but she taught me how to do it.” [child]

Other parents described motivation difficulties and motivating children who resisted exercising on the bike:

Yeah, I’ll be honest, until very lately, it has been hard to get him to have to do it. A bribe. You know, you bribe him. Whether it be “after you do this, you can have this to eat” or “you can do your video game after this.” [parent]

Thus, motivators also included tangible rewards during or after exercise sessions such as watching TV while exercising or playing video games. “He liked it because he was able to watch TV while he did it.” [parent]

Some parents became exercise partners with their children by sharing the bike for their own fitness routines. In one case, a parent added a second exercise bike to accompany the child. “‥about half way into the study, we got another bike and the other bike is for yours truly and we sort of have these competitions that we go through.” [father]

Health benefits

Several children and parents drew motivation to perform the bicycle exercise from physical benefits such as “feeling better” after the exercise, reduction in required antibiotic therapy, and pulmonary function test improvements. Although unusual for children with CF who are generally underweight, one dyad valued weight reduction as a benefit of the exercise program. Several children perceived benefits from the exercise program to their breathing, “You feel like you can breathe better sometimes.” [child] “He doesn’t like to exercise. But he knows that his PFTs [pulmonary function tests] are better when he exercises.” [parent] A 10-year-old boy described his experience and perception of improved exercise tolerance after six weeks on the bike exercise program, “Like whenever I run a lot. I don’t like keep coughing and stuff. It makes me—like I can breathe better whenever I run.” [child].

The general health and conditioning benefits of exercise were internal motivators or rewards expressed by several families. For example, a 16-year-old boy and his parents perceived the bicycle exercise as good conditioning for wrestling. To “keep moving” was highly valued, especially by parents. Specifically, exercise was viewed as a life extender. A parent spoke openly about CF as a life limiting disease and the child's recognition of that reality:

You know, she knows there is no cure and sometimes she will get down on that. She knows eventually it will take her life, but now, the studies she participates in—I think it makes her more positive that there are things she can do to increase that life span. [mother]

The features of the bicycle and OMNI Scale were viewed positively by some children:

I like how it gives you your heart rate so you see how fast I’m going. I like to see how far I can go and try to reach my goal and trying to beat what I did the last time. [child]

Personality traits

Parents and children also described personality characteristics of the child that promoted or influenced adherence to planned exercise sessions, e.g., self-motivated, “goal-oriented,” “organized,” “and thank God she is like the police. She is like FedEx or something.” [mother] “He is not one to sit on the couch with a book or something. He is not one to sit around and do nothing.” [mother] Conversely, one mother explained how the exercise program counterbalanced a sedentary personal/family characteristic, “we are not really exercise people so it is good that he is doing it and getting exercise.”

Barriers

Our participants cited several barriers to maintaining the prescribed bicycle exercise program. Competing activities, priorities, and responsibilities were the most common barriers that participants prevented participation in the exercise program. “Busy schedules” were a primary barrier to exercise for these children who described daily schedules that include daily treatments (up to three times a day) for CF, schoolwork, vacation travel, shared custody, and activities:

…of course our lives have been completely chaotic since right before school started, but I know she is not doing it the way she is supposed to be doing it lately. She is kind of slacking off a little bit. Part of it is because she has not been feeling that well lately, and partly it is just because of time constraints. [father]

There was actually a whole week where she wasn’t able to do it because they were going with their dad for like five days at a time every couple of weeks there for a couple of months and um and then the days otherwise, you know it was just a matter of having, you know, the running around and not enough time and I had some family issues going on so it kind of fell on the back burner as not, you know, priority. [mother]

I’ll question her as to whether or not she has been doing it. You know, I try to pay as much attention as I can. Sometimes I’m not home in the evenings. I’ll be out running errands. Our youngest has cheerleading. My son has scouts and also has Confirmation classes going on right now. So it is pretty much running at least four nights a week. And usually try to ask her a couple of times here and there, have you done it, are you doing it? Just try to prod her along when I can remember. Which unfortunately is not (laughing)…It is not as high on the priority list as you know doing the vest and blood sugars and everything like that and everything else with her so, it kind of falls behind sometimes. [father]

Seasonal activity fluctuations were evident in children and parents’ descriptions of activity and exercise before and during participation in the experimental exercise program. The stationary bicycle was seen as beneficial during the winter months but less so in the summer. “But like in the wintertime she wouldn’t do a lot. In the summer time she would bike and swim.” [mother] Most children were reportedly more active in the summer, playing outside, swimming, biking, engaging in organized sports activities (basketball, football, and baseball), and vacation travel with their families. While the freer schedule in summer provided additional time for some children to maintain the exercise bike schedule, others found “fitting it in” more difficult in the summer:

I think she doesn’t like using the bike because it is indoors and it has been summer so it has been pretty easy for her to be outside doing her exercise…and I think the only thing about the bike is that it is indoors; but once fall hits, she is not going to have a problem with it. [parent]

I think it is easier for him in the wintertime than the summer because in the summer he is outside mowing lawns, running the rotor tiller, all kinds of stuff. He likes being outside so. [mother]

The exercise program was accepted by parents and children to the extent that it did not interfere with participation in valued activities such as sports, outdoor activities, school, or church events. Parents supported missing the scheduled bike exercise in favor of their child “not missing out” on these normal, valued activities. This concern for “not missing out” was framed in the context of the time already spent by their children in CF treatments each day and balanced by the perceived benefits of the competing or substitute activity.

For example, one mother noted that her son sometimes missed the bike exercise time to sing in the choir but that was allowable to her because she viewed singing as a form of exercise for the lungs:

Usually a volleyball game or he really likes to sing and sometimes he is with a group of young folks that gets together to sing. So it was either volleyball or singing. I told him again, you are not really missing out on exercising your lungs, because if you are singing, it is a different exercise. So, yeah it was usually one of those two things… [mother]

Effort and Work

Although the bicycle was described as “fun” by several children, most acknowledged or described the bicycle exercise as a difficult effort or hard work. The experience of performing the bike exercise was described by children with CF in terms ranging from “easy” (at the beginning of the session) to “hard work” or “tiring” (at the higher levels of difficulty):

At first you feel like you kind of don’t want to do it because you haven’t really gotten to exercise all day. So you are like trying to be awake at the same time. Trying to be strong. Once you get into the second lap—like before 7 (on the OMNI scale) you start feeling it—you feel better. Yep (laughter) you start feeling the heat of it. [child]

For some children, the exercise experience was energizing; but it also left children feeling tired:

…You don’t feel like ahhh all the time like all tired and exhausted and everything but sometimes you do after riding it and doing everything else and then you feel exhausted but it is not exhaustion from feeling bad about it. It’s like a good thing, like an accomplishment. [child]

Perceptions of energy and work were interrelated with motivators and barriers. For example, a 12-year-old girl described feeling “more energetic,” “healthier,” and empowered (“you feel like you want to do anything you want”) after the exercise. [child] She associated the “warming up” pace at the beginning of the exercise session with “waking up. The children’s descriptions of how they felt during and after the exercise ranged on a continuum of energy depletion (tiring) to energizing.

Exercise Routine

Integration of the exercise program into the CF routine was evident in the participants’ descriptions of adding the bike to the daily CF treatment routine, usually in the evening following vest treatment. This integration did not change the CF treatment routine, which the parents and children clearly prioritized over exercise. “Sometimes he would do the vest before the bike. He has (emphasis added) to do the vest.” [parent] Although school days were busy with after-school activities and the demands of routine CF therapies, the structure of the school day and evening seemed to provide a reminder or space to fit the exercise bike into the daily CF treatment routine. Integration of the exercise program into the CF routine was linked to the barrier or difficulty imposed by busy family schedules:

Interviewer: What is the most difficult part?

Mother: Ahhh (thinking) well, I would just say getting our schedules. He doesn’t do it by himself, so I’m sitting there. So sometimes we don’t do it until later in the night or whatever. [mother]

Sustaining the Exercise Program

While the experience was generally described by children as positive, their enthusiasm waned over the six-month intervention period. We identified a pattern for some participants in which the “novelty (of the bike) wore off,” leading to rebellion or conflict. Then the novelty wore off and it got a little more of a struggle to get him on the bike to do it." [parent] “…I think that of course, she is just little and at first she was very excited about it. Now it is becoming a chore to do” [parent]:

It was fun at first to have to do it and to have to, you know, figure out how fast, you know, to pace himself and all of that. Then, a couple of months into it, you know, it wasn’t so fun. He didn’t want to have to ride the bike. He didn’t want to have to do it. It was a fight to get him on it. [parent]:

Interviewer: And like how many times a week do you think you are exercising now?

Child: Like once…or twice a week.

Interviewer: Ok. Ok. When you do exercise, how do you feel?

Child: Good.

Interviewer: Good? On the bike or other exercise?

Child: Outside activities are good - but on the bike ahhhh, I don’t want to. Like (it makes me) mad. [child]

She did really impressive at first, ahhh, the last month and a half or so it has been kind of lax. She is doing it less frequently, when she does do it I don’t think she does it for quite as long. It is definitely less often… [children] get burned out after a while. [father]

For some children, the exercise bike seemed to be a new symbol or reminder of CF. One parent described their child’s shift from initial enthusiasm to “hating” the bike exercise: “we have heard more in the last six months 'I hate having CF' while he is riding the bike, and 'why do I have to do it?'”

Limitations

This study is limited by the artificial (clinic) setting of the interviews wherein participants may have been influenced by bias toward a socially desirable or expeditious response. The bicycle exercise program in the home was not actually observed. This limitation was addressed by conducting individual, serial interviews (at two months and six months) separately with each parent and child to obtain multiple perspectives and engagement with participants over time. Transferability of study findings may be limited by the sampling pool which was drawn from a single regional CF treatment and research center located in the Mid-Atlantic region of the U.S. Participants were primarily middle class, Caucasian, and may have been more interested in exercise than the general population of patients with CF, given their voluntary participation in the exercise study. Participation in the primary study may limit transferability, given that participants were enrolled in a study that offered incentives (e.g., payment and a bicycle), and included weekly phone calls. However, maximum variability was achieved in the sample on gender and age of school-aged children. Family configurations included single parents, shared custody, and families in which there are multiple children with CF.

Discussion

A qualitative descriptive study was conducted, nested within a clinical trial to ascertain the patient and family experience of an exercise program designed for CF patients. The qualitative approach revealed important information about motivation to implement and sustain an exercise regimen and parent-child experiences while participating in research activities. The findings enhance understanding of attitudes regarding the value of physical activity and exercise in this setting. In prior studies, some children with CF were reported to perceive themselves to be no different from their peers, capable of “doing anything” related to physical activity (Orenstein et al., 2004), while others expressed concerns that their participation in physical activity was limited by barriers, including physical discomfort, boredom (Swisher & Erickson, 2008), time required for other treatments (Moola et al., 2012), and varying health status (Prasad & Cerny, 2002). The findings regarding barriers to exercise participation are similar to those identified regarding the need to perform secretion clearance techniques, e.g., “not enough time”, “do not enjoy”, “do not believe it helps”, “no motivation”, suggesting resistance to performing routine daily treatment-related actions is not unique to exercise participation (Flores et al., 2013).

In the study, parents and children noted health benefits, both actual and potential, as a motivator to participate in the exercise program. The findings support that children and teenagers with CF generally have positive attitudes toward physical activity exemplified by their participation in sports, and other exercise-related activities within and outside of the study protocol. Many children with CF seem to understand the importance of exercise for health reasons (Dunton et al., 2012; Rand & Prasad, 2012; Swisher & Erickson, 2008). Positive beliefs regarding exercise participation and other aspects of the CF regimen were shared equally by both genders. Similar to a prior study which explored relationships between illness perceptions, treatment beliefs, and reported adherence in adolescents with CG, there were no detected gender differences in reports of barriers, motivators or plans to sustain the exercise program (Buck et al., 2009)

From a study of children with CF (Smith et al. 2010), ages 7–17 years, recruited from a CF Center in New York, reported depressive symptoms in approximately 20% (29% for children; 35% for mothers; 23% for fathers). Although speculative, measure depressive symptoms in those involved in our study were not measured, and there was no indication of depressive symptoms in the participants. Parents were described as motivators and facilitators and attracted to the study by its potential health benefits. Children were described as “self-motivated,” “goal-oriented,” and actively involved in competing activities. In both studies, participants were recruited by a letter sent from the CF Center describing study goals. It is possible that those attracted to a study focused on exercise might differ from those attracted to a study with differing goals, a factor that needs to be considered when evaluating representativeness of findings (Brody, Turner, Annett, Scherer, & Dalen, 2012).

These findings suggest that parents placed a high value on exercise. Parents verbalized their opinion that, by improving aerobic fitness, exercise can help to extend longevity, and that children, including those with the most extreme disease severity, could benefit from participating in physical activity. The parents shared positive beliefs with the children about the benefits of exercise, and felt that having a chronic disease was not a barrier to their child’s participation in organized sports or recreational activities. Like the parents of children with different chronic illnesses (Fereday et al., 2009), our participants revealed that facilitating the exercise did require vigilant planning and management, and considerable parental support.

The study adds to the literature on acceptability and sustainability of psychobehavioral interventions in chronic illness, particularly exercise interventions (Adeniyi & Young, 2012). Although the data showed acceptability of the behavioral intervention, enthusiasm and motivation waned in the final months of the program for several child-parent dyads. Similar attitudes were described among children with cancer participating in a community-based exercise program (Takken et al., 2009). Sustaining healthy behaviors or lifestyle/behavioral change is an ongoing challenge for exercise and behavioral health interventions. Children with CF and their parents have additional burdens of balancing a complex daily treatment regimen with normal activities of family life. These children clearly were engaged in many social and recreational activities including a variety of sports, music and scouting. In a qualitative study of the strategies for and difficulties of adhering to chest physiotherapy for CF, parents motivated children with visualization and distraction strategies (Cohen-Cymberknoh et al., 2011). Williams’ participants reported that the chest physiotherapy was “boring,” a sentiment shared by several of the participants when discussing the bicycle exercise program during the second (six-month) interview.

Children who participated in this study described their body’s response (e.g., speed, heart rate), and progress toward goals (e.g., OMNI scale, distance) as motivators. Television seemed to work as a distraction in our study, as children and their parents frequently reported “watching TV” during the exercise session as a motivator or positive reward. Participants also used competition and family support as motivators. More research is needed to individualize and capitalize on the use of visualization, distraction, and gaming in promoting adherence to exercise interventions among children with chronic health disorders (Rand & Prasad, 2012).

Although clinical trials yield beneficial information, they can cause adverse effects. The exercise intervention tested in the primary study required daily participation, an expectation that added time to the complex CF regimen. This was viewed as a concern because the CF secretion clearance regimen can require up to three hours a day. Therefore, probes designed to elicit any change in the regimen in the interviews were included—and there were no modifications identified. Children carried out their prescribed regimen and, if time conflicts developed, omitted bicycle exercise. We are unaware of any other studies that investigated tradeoffs made by children with CF as a result of added research study expectations. It was encouraging to discover that no adverse effects occurred that related to the management of their chronic illness.

An additional concern was that study participation might alter family dynamics as parents were asked to encourage and monitor adherence to the exercise regimen. The study revealed varying responses. In some situations, the parents joined in the exercise, using the bike provided for the study or another bicycle. The interviews identified situations in which parents acted as facilitators by reminding, coaching/encouraging, recordkeeping, rewarding, and by “making the time” in the family schedule for the child to exercise. For some the experience, while initially described as positive, became less so over time. Novelty of the bike lessened and parents’ efforts to encourage adherence led to conflict. Parents and children described this consequence in a manner consistent with “usual” parent-child conflicts. The study was unable to discern any negative impact on family dynamics. However, the study did not directly measure this outcome.

Parents and children in the study revealed a variety of motivators to participate in the exercise program in addition to the health benefits of exercise. For some, the motivation to participate was altruistic, i.e., a desire to support the medical care team or related to family values about volunteering (Broome & Richards, 2003). Several dyads noted they participated in several prior trials because they felt their efforts might advance knowledge of the disease or its cure. Others cited more pragmatic motivators, e.g., incentive payments or the ability to have and keep the bicycle. These parent-child dyads were open about the impact of research participation and their commitment to continue the regimen, or not continue it, after the end of the study.

With the well-documented correlation between exercise tolerance, and both survival and health-related quality of life, exercise represents a critical treatment focus for CF patients. Nurses contribute to standard exercise rehabilitation programs, through education, psychosocial support, and communication. Nurses can apply these study results to query and support children and parents in planning exercise programs as a part of the CF treatment regimen. Any negative impact on the parent-child dyad or maintenance of the CF regimen as a result of study participation was unidentified. This finding should lessen concern regarding participation in studies that require parental supervision and monitoring of child actions in following the study protocol. However, motivators were identified for study participation that related to potential health benefits and study incentives. These findings support the need to measure rationale for study participation as a means of understanding motivators and long term benefit of behavioral lifestyle interventions.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Dr. Janet Stewart, Professor and Dean Faculty of the Health Sciences Kibogora Polytechnic, Rwanda, and National Institute of Nursing Research, R01NR9285 (Orenstein).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Contributor Information

Mary Beth Happ, The Ohio State University College of Nursing and University of Pittsburgh School of Nursing.

Leslie A. Hoffman, Nursing and Clinical.

Linda W. Higgins, University of Pittsburgh School of Nursing, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Department of Pediatrics, and Donald D. Wolff Jr. Center for Quality, Safety, and Innovation at UPMC.

Dana DiVirgilio, University of Pittsburgh School of Nursing.

David M. Orenstein, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Department of Pediatrics, Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh of UPMC, and University of Pittsburgh School of Education, Department of Health and Physical Activity.

References

- Adeniyi FB, Young T. Weight loss interventions for chronic asthma. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2012;7:CD009339. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009339.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody JL, Turner CW, Annett RD, Scherer DG, Dalen J. Predicting adolescent asthma research participation decisions from a structural equations model of protocol factors. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2012;51:252–258. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broome ME, Richards DJ. The influence of relationships on children's and adolescents' participation in research. Nursing Research. 2003;52:191–197. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200305000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucks RS, Hawkins K, Skinner TC, Horn S, Seddon P, Horne R. Adherence to treatment in adolescents with cystic fibrosis: The role of illness perceptions and treatment beliefs. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2009;34:893–902. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsn135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cholewa JM, Paolone VJ. Influence of exercise on airway epithelia in cystic fibrosis: A review. Medicine in Science in Sports and Exercise. 2012;44:1219–1226. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31824bd436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen-Cymberknoh M, Shoseyov D, Kerem E. Managing cystic fibrosis: Strategies that increase life expectancy and improve quality of life. American Journal of Respiratory & Critical Care Medicine. 2011;183:1463–1471. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201009-1478CI. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creswell JW, Plano Clark VL. Designing and conducting mixed methods research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publishing; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Cystic Fibrosis Foundation. Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Patient Registry: Annual Data Report 2010. 2010 Retrieved from www.cff.org/UploadedFiles/LivingWithCF/CareCenterNetwork/PatientRegistry/2010-Patient-Registry-Report.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Deatrick JA, Ledlie SW. Qualitative research interviews with children and their families. Journal of Child and Family Nursing. 2000;3:152–158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunton GF, Berrigan D, Ballard-Barbash R, Perna F, Graubard BI, Atienza AA. Differences in the intensity and duration of adolescents' sports and exercise across physical and social environments. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport. 2012;83:376–382. doi: 10.1080/02701367.2012.10599871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dwyer TJ, Elkins MR, Bye PT. The role of exercise in maintaining health in cystic fibrosis. Current Opinion in Pulminary Medicine. 2011;17:455–460. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0b013e32834b6af4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fereday J, MacDougall C, Spizzo M, Darbyshire P, Schiller W. “There's nothing I can't do—I just put my mind to anything and I can do it”: A qualitative analysis of how children with chronic disease and their parents account for and manage physical activity. BMC Pediatrics. 2009;9:1. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-9-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flores JS, Teixeira FA, Rovedder PM, Ziegler B, Dalcin TR. Adherence to airway clearance therapies by adult cystic fibrosis patients. Respiratory Care. 2013;58:279–285. doi: 10.4187/respcare.01389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: Concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Education Today. 2004;24:105–112. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruber W, Orenstein DM, Braumann KM. Do responses to exercise training in cystic fibrosis depend on initial fitness level? European Respiratory Journal. 2011;38:1336–1342. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00192510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins LW, Robertson RJ, Kelsey SF, Olson MB, Hoffman LA, Rebovich PJ, Orenstein DM. Exercise intensity self-regulation using the OMNI scale in children with cystic fibrosis. Pediatric Pulmonology. 2013;48:497–505. doi: 10.1002/ppul.22639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles M, Huberman A. Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook. (2nd ed.) Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publishing; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Mogayzel PJ, Naureckas ET, Robinson KA, Mueller G, Hadjiliadis D, Hoag JB, Marshall B. Cystic fibrosis pulmonary guidelines: Chronic medications for maintenance of lung health. American Journal of Respiratory & Critical Care Medicine. 2013;187:680–689. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201207-1160oe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moola FJ, Faulkner GE, Schneiderman JE. No time to play: Perceptions toward physical activity in youth with cystic fibrosis. Adapted Physical Activity Quarterly. 2012;29:44–62. doi: 10.1123/apaq.29.1.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moorcroft AJ, Dodd ME, Morris J, Webb AK. Individualised unsupervised exercise training in adults with cystic fibrosis: A 1 year randomised controlled trial. Thorax. 2004;59:1074–1080. doi: 10.1136/thx.2003.015313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nixon PA, Orenstein DM, Kelsey SF. Habitual physical activity in children and adolescents with cystic fibrosis. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 2001;33:30–35. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200101000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orenstein DM, Hovell MF, Mulvihill M, Keating KK, Hofstetter CR, Kelsey S, Nixon PA. Strength vs aerobic training in children with cystic fibrosis: A randomized controlled trial. Chest. 2004;126:1204–1214. doi: 10.1378/chest.126.4.1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paranjape SM, Barnes LA, Carson KA, von Berg K, Loosen H, Mogayzel PJ. Exercise improves lung function and habitual activity in children with cystic fibrosis. Journal of Cystic Fibrosis. 2012;11:18–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2011.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prasad SA, Cerny FJ. Factors that influence adherence to exercise and their effectiveness: application to cystic fibrosis. Pediatric Pulmonology. 2002;34:66–72. doi: 10.1002/ppul.10126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rand S, Prasad A. Exercise as part of a cystic fibrosis therapeutic routine. Expert Review of Respiratory Medicine. 2012;6:341–352. doi: 10.1586/ers.12.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson RJ, Goss FL, Boer NF, Peoples JA, Foreman AJ, Dabayebeh IM, Thompkins T. Children's OMNI scale of perceived exertion: Mixed gender and race validation. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 2000;32:452–458. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200002000-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski M. Whatever happened to qualitative description? Research in Nursing & Health. 2000;23:334–340. doi: 10.1002/1098-240x(200008)23:4<334::aid-nur9>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneiderman-Walker J, Pollock SL, Corey M, Wilkes DD, Canny GJ, Pedder L, Reisman JJ. A randomized controlled trial of a 3-year home exercise program in cystic fibrosis. Journal of Pediatrics. 2000;136:304–310. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2000.103408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selvadurai HC, Blimkie CJ, Meyers N, Mellis CM, Cooper PJ, Van Asperen PP. Randomized controlled study of in-hospital exercise training programs in children with cystic fibrosis. Pediatric Pulmonology. 2002;33:194–200. doi: 10.1002/ppul.10015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith BA, Modi AC, Quittner AL, Wood BL. Depressive symptoms in children with cystic fibrosis and parents and its effect on adherence to airway clearance. Pediatric Pulmonology. 2010;45:756–763. doi: 10.1002/ppul.21238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swisher AK, Erickson M. Perceptions of physical activity in a group of adolescents with cystic fibrosis. Cardiopulmonary Physical Therapy Journal. 2008;19:107–113. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takken T, van der Torre P, Zwerink M, Hulzebos EH, Bierings M, Helders PJ, van der Net J. Development, feasibility and efficacy of a community-based exercise training program in pediatric cancer survivors. Psycho-Oncology. 2009;18:440–448. doi: 10.1002/pon.1484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turchetta A, Salerno T, Lucidi V, Libera F, Cutrera R, Bush A. Usefulness of a program of hospital-supervised physical training in patients with cystic fibrosis. Pediatric Pulmonology. 2004;38:115–118. doi: 10.1002/ppul.20073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van de Weert-van Leuuwen PB, Slieker MG, Hulzebos HJ, Kruitwagen CL, van der Ent CK, Arets HG. Chronic infection and inflammation affect exercise capacity in cystic fibrosis. European Respiratory Journal. 2012;39:893–898. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00086211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]