Abstract

Purpose

The objective of this study was to evaluate the early results of a custom non-fluted diaphyseal press-fit stem for use with the global modular replacement system (GMRS) tumour prosthesis and the early complications associated with this implant.

Methods

A total of 53 patients (54 implants) were identified from a prospective database where a custom non-fluted diaphyseal press-fit stem was used as part of the reconstruction of the limb. All patients had a minimum of 22 months of follow-up.

Results

The rates of stem revision for any reason were calculated. The median follow-up was 36 months (range 22–85 months). Aseptic loosening was not observed in any patient.

Conclusions

At early term follow-up, an uncemented non-fluted stem used with the GMRS tumour endoprosthesis provides a stable bone-prosthesis interface with no evidence of aseptic loosening.

Keywords: Megaprosthesis, Aseptic loosening, Stem revision

Introduction

Current treatment for malignant extremity bone sarcomas such as Ewing’s sarcoma or osteosarcoma includes a combination of chemotherapy and limb salvage surgery [1, 2]. Currently, limb salvage surgery is accepted as the gold standard in orthopaedic oncology and, following tumour resection, frequently involves limb reconstruction with an endoprosthesis [3, 4]. Due to modern advances in chemotherapy, many patients with these and other malignant bone sarcomas will go on to have a relatively normal lifespan [1, 2]. Consequently the durability and longevity of these endoprosthetic implants is of great importance [5].

The optimal method of fixation of the tumour endoprosthesis to the patient’s native bone remains controversial [6]. Historically, cemented prostheses were used due to their excellent early biomechanical interface with the host bone and immediate stability allowing for early weight-bearing [7]. Unacceptable rates of aseptic loosening seen with cemented prostheses have pushed many surgeons to look for uncemented prostheses that offer biological fixation and the possibility of better long-term results [8–10]. One commonly used endoprosthesis, the Stryker global modular replacement system (GMRS), has a solid, forged stem with a plasma-sprayed hydroxyapatite-coated surface for press-fit uncemented implantation.

While ingrowth of such endoprostheses occurs in the majority of patients, the initial rotational stability of uncemented stems used for tumour reconstruction remains an area of concern. Compared to an older type of uncemented tumour endoprosthesis, the Kotz modular femoral tibial resection system (KMFTR), which was manufactured with a side plate to allow for improved rotational stability, the GMRS system was manufactured with derotational flutes in the stem [10]. These derotational flutes supposedly add initial rotational stability to the reconstruction; however, their utility has been questioned. It is not known if these derotational flutes are truly necessary to provide adequate initial rotational stability or whether the interface between the bone and the hydroxyapatite-coated surface of the press-fit stem is sufficient. Despite the derotational side plate manufactured on the Kotz prosthesis, many surgeons found the rotational stability of this prosthesis adequate without addition of cross screws. Furthermore, the derotational flutes pose several significant problems during insertion as tracts must be drilled in the endosteal cortex to accommodate the derotational flutes, and these tracts serve as significant points of stress concentration, which can lead to bone fracture during stem insertion. In addition, as these tracts must be pre-drilled prior to stem insertion, changes to the rotational position of the implant in the bone cannot be made during insertion.

Due to our concerns that the derotational flutes were unnecessary, we previously reported on a series of custom uncemented GMRS stems without derotational flutes, as well as the very similar Stryker Restoration stems, inserted in a cadaver model and showed adequate initial biomechanical stability [11]. Based on these results, we have been using these two uncemented stems that both lack derotational flutes for oncological reconstruction. Initially, with the use of custom adapters, the GMRS system was used in concert with the Stryker Restoration stem, a well-recognised revision style ingrowth stem. More recently, we have used the custom GMRS press-fit stem that lacks derotational flutes. The goal of this study was to report on the early results of these non-fluted diaphyseal press-fit uncemented tumour prosthesis stems for oncological reconstruction.

Materials and methods

Following Research Ethics Board approval, we reviewed the records of patients treated at our institution with resection of a primary malignant bone tumour of the proximal femur, distal femur or proximal tibia followed by reconstruction with either a Stryker Restoration stem and custom GMRS adapter or our custom GMRS stem between April 2005 and May 2012. Patients were identified from our prospectively collected tumour database and data were gathered after review of patients’ medical records.

Patients were categorised into two cohorts. Cohort 1 consisted of patients where a Restoration stem and custom GMRS adapter were used. Cohort 2 consisted of patients where a custom non-fluted GMRS stem was used. All implants were made and manufactured by the Stryker Corporation. All patients had a minimum of 22 months of follow-up. Demographic and treatment details were collected.

Evaluation of the bone to prosthesis interface was made by physical and radiographic evaluation. On follow-up, patients were questioned about pain and/or instability in the operated extremity and routine physical examination manoeuvres evaluating gait, range of motion and strength were performed and documented. Bi-planar radiographs were used to assess the bone to prosthesis interface. Radiographic variables of ingrowth including bone bridging, spot welding, resorption, subsidence, neocortex formation and pedestal formation were all used to determine whether the prosthesis had ingrown [12–14]. Resorption was categorised using the longest dimension in either the medial/lateral or proximal/distal planes as mild (less than five millimetres), moderate (five to ten millimetres) or severe (over ten millimetres). Radiographically detectable stem subsidence was measured by comparing the immediate post-operative radiograph to subsequent imaging studies. Subsidence was categorised as mild (under five millimetres), moderate (five to ten millimetres) and severe (over ten millimetres). In addition to the radiographic interpretation provided by the treating surgeon and the musculoskeletal radiologist at each follow-up, two experienced readers independently evaluated each stem radiographically to document the aforementioned radiographic variables used to determine bone ingrowth.

Complications related to stem implantation and survival were collected, including prosthetic fracture, periprosthetic fracture, infection, aseptic loosening and delayed wound healing/wound breakdown. The rates of stem revision for any reason were calculated. Time to failure was defined as the interval between the date of endoprosthetic reconstruction and the date of onset of the reason for failure (rather than the date of device removal). After early post-operative follow-up, all patients were seen every three months for the first two years and then every six months for the next three years, and yearly thereafter. All data were analysed using SPPS version 19 software.

Results

A total of 53 patients (54 implants) were identified from our database that met inclusion criteria. Forty-nine uncemented non-fluted stems were implanted following resection of tumour and six implants were placed for revision of a failed endoprosthesis. Cohort 1 consisted of 33 patients who had a Restoration stem implanted using a custom GMRS adapter. Cohort 2 consisted of 20 patients who had a custom non-fluted diaphyseal press-fit uncemented stem as part of their endoprosthesis reconstruction.

The median follow-up was 36 months (range 22–85 months). The mean stem size was 15 mm (range 12–20 mm). Thirteen stems were inserted into the middle third of the tibia as part of a knee endoprosthesis (Fig. 1). Six stems were inserted into the middle third of the femur as part of a hip endoprosthesis (Fig. 2). Thirty-five stems were inserted into the middle third of the femur as part of a knee endoprosthesis (Fig. 3 and Table 1). In the Restoration stem with GMRS adapter group (cohort 1), there were two intra-operative fractures that required cerclage wiring of the bone prosthesis junction, while two adapters broke post-operatively requiring surgical revision with adapter exchange. There were no insertion fractures or mechanical failures in the custom GMRS group (cohort 2). In total, five stems had to be revised or removed for infection and three stems for tumour progression.

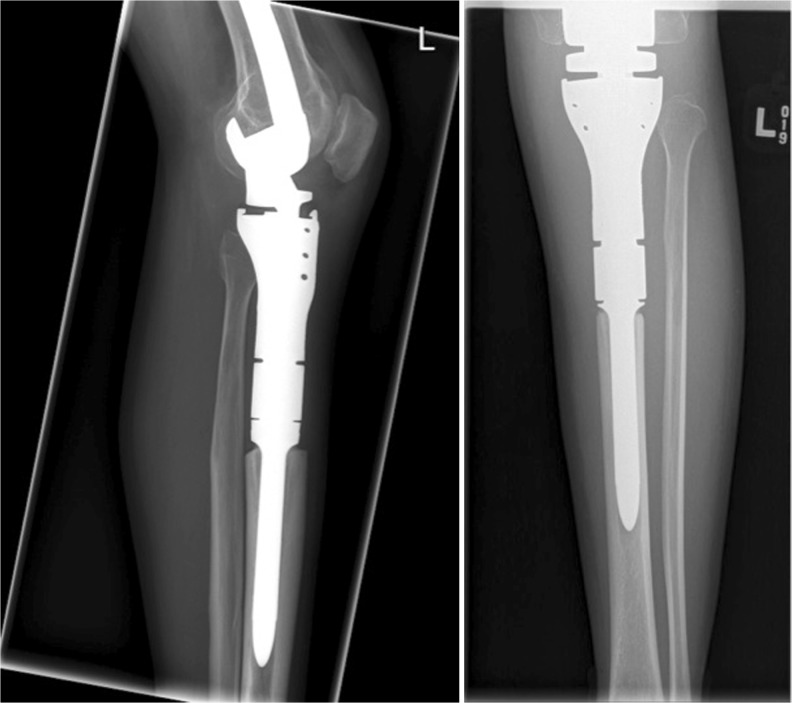

Fig. 1.

Radiographs of the non-fluted stem inserted after proximal tibial resection as part of knee reconstruction

Fig. 2.

Radiographs of the proximal femoral resection and reconstruction using the custom non-fluted stem inserted as part of hip reconstruction

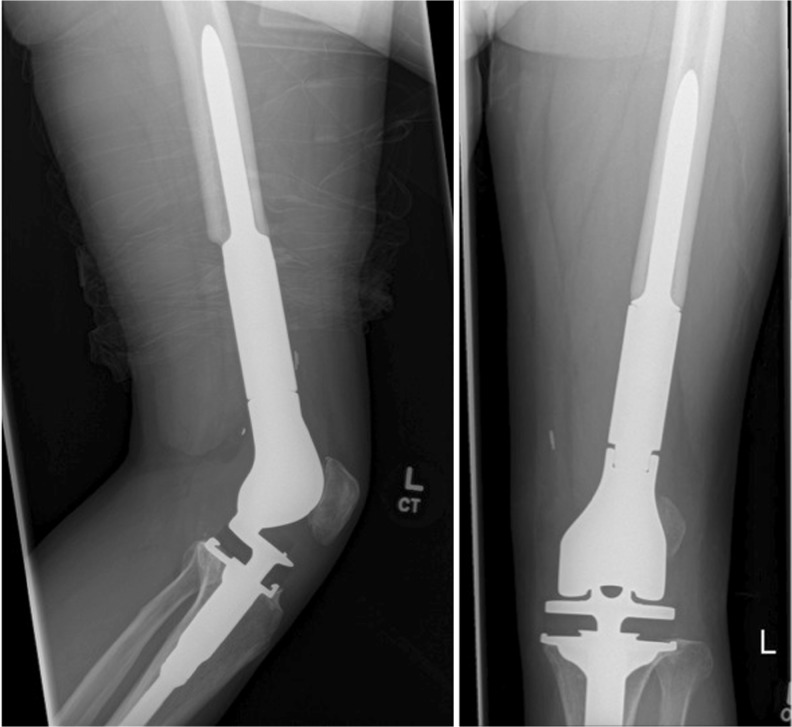

Fig. 3.

Radiographs of the custom non-fluted stem inserted after distal femoral resection as part of knee reconstruction

Table 1.

Site of reconstruction of patients with the custom non-fluted stem

| Site of reconstruction | No. of implants |

|---|---|

| Proximal tibia | 13 |

| Proximal femur | 6 |

| Distal femur | 35 |

Aseptic loosening was not observed in any patient in either cohort. Using the radiographic variables of bone bridging, spot welding, subsidence, resorption, neocortex formation and pedestal formation, bone ingrowth was identified in all stems except the five stems revised for infection and three revised for tumour progression. Resorption was identified in a total of three of the 54 stems. Two stems showed mild resorption in Gruen zones 6 and 7. One stem showed moderate resorption in the medial distal femur at the stem tip, zone 5; however, this was in a patient with intra-operative fracture that required cerclage wiring. Each of these three stems with resorption showed areas of significant bone ingrowth with spot welding along the entirety of the stem. Mild stem subsidence (under five millimetres) was noted in one patient at early follow-up (six months). This subsidence did not change on long-term follow-up once radiographic signs of bone ingrowth were apparent. No patient had radiographically identifiable pedestal or neocortex formation.

Discussion

Due to improvements in chemotherapeutics, patients with malignant bone tumours are living longer and consequently the longevity of the endoprostheses used for reconstruction of their limb is vitally important [1–3]. While debate exists regarding the optimal method of fixation of the endoprosthesis to the host bone, many surgeons now prefer using uncemented stems as they allow for biological fixation at the host-stem junction that can respond and change depending on the needs of the patient [5, 8, 9]. The GMRS is a commonly used endoprosthetic system whose uncemented stem is manufactured with derotational flutes, which are unique to this implant among the various manufacturers of tumour endoprostheses. The purpose of these derotational flutes is intended to immediately provide rotational stem stability after implantation while bone is growing onto the hydroxyapatite coating for long-term stability.

Two specific problems exist regarding the derotational flutes of the GMRS endoprosthesis stem: (1) they require drilling of specific channels into the endosteal cortical bone to allow for insertion, and these channels serve as points of stress concentration which can ultimately lead to fracture during stem insertion; (2) drilling of these channels does not allow the surgeon to alter the rotation of the endoprosthesis within the bone. Due to these concerns, we have instead used uncemented non-fluted stems with the GMRS endoprosthesis. Initially, a custom adapter allowed linkage of the Stryker Restoration stem to the GMRS endoprosthesis. More recently, we have employed a custom GMRS non-fluted uncemented prosthesis. The results of this study show that the initial concerns regarding the possible lack of inherent rotational stability of a non-fluted prosthesis and the need for anti-rotational flutes are unwarranted.

Our group previously reported on the biomechanical performance of two uncemented non-fluted stems inserted in a cadaver model, one custom made for the GMRS prostheses and another very similar stem known as the Restoration [11]. In this study, the uncemented non-fluted Restoration stems were inserted into a series of cadaver femora and all constructions were mechanically tested in axial compression, lateral bending, torsional stiffness and torque to failure. The applied torsion to failure of the non-fluted Restoration stem suggested it would be fully able to withstand the early post-operative torsional forces without failure. Comparison of the Restoration stems to the non-fluted GMRS stems suggested the non-fluted GMRS stems had similar, if not better biomechanical performance. This study suggests that the initial biomechanical stability of the non-fluted GMRS implant is adequate.

The most common method of endoprosthesis failure in this series was infection. Infection continues to be a substantial problem affecting endoprosthetic reconstruction after resection of malignant bone tumours. Factors related to the length/extent of surgery, chemotherapy-induced immunosuppression and amount of soft tissue available for coverage are directly related to a patient’s risk for infectious complications. Henderson et al. reviewed the modes of failure for tumour endoprostheses in a retrospective multi-institution study [15]. They found that in 2,174 patients the most common mechanism of failure in their series was infection, occurring in 34.1 % of cases. Aseptic loosening accounted for 19.1 % of all failures in their study, which historically has been the most common method of failure. This change in the common mechanisms of failure may reflect the historical bias towards cemented tumour endoprostheses. The current trend towards the use of press-fit stems may lead to lower rates of aseptic loosening in the future, such as we reported with the Kotz system previously [10, 16].

The major limitation to our study is the short duration of patient follow-up. While the average length of patient follow-up in our series is 40.6 months, 90.5 % (48 of 53) of these patients have a minimum of two years of follow-up. However, we believe that even one year of follow-up will be sufficient for patients with uncemented tumour endoprosthesis stems. Due to the biomechanical issues related to limb reconstruction for oncological indications, the endoprosthesis is often subjected to significant forces at the bone-prosthesis junction because of the long lever arm of the prosthesis. Consequently, any failure of ongrowth to the stem at the bone-endoprosthesis junction would be likely to cause aseptic loosening very early in the post-operative period. Therefore, due to the large size of the endoprostheses and the high loads placed on the stem-bone junction, we hypothesise that aseptic loosening or failure of formation of the biological stem-bone interface would be readily apparent even at this early term of follow-up.

In conclusion, we present the early results of a custom non-fluted diaphyseal press-fit uncemented tumour prosthesis stem and demonstrate no aseptic loosening. The combination of in vitro biomechanical prosthesis evaluation previously reported for this series of patients in which the non-fluted prosthesis was successfully used clinically indicates that initial concerns regarding the rotational stability of this uncemented non-fluted prosthetic stem were unwarranted. Derotational flutes are unnecessary for initial rotational control, are associated with insertion problems including bone fracture or implant rotation and lack of these flutes is not associated with aseptic loosening in our series of patients at early term follow-up.

References

- 1.Sampo M, Koivikko M, Taskinen M, Kallio P, Kivioja A, Tarkkanen M, Böhling T. Incidence, epidemiology and treatment results of osteosarcoma in Finland—a nationwide population-based study. Acta Oncol. 2011;50(8):1206–1214. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2011.615339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sampo MM, Tarkkanen M, Kivioja AH, Taskinen MH, Sankila R, Böhling TO. Osteosarcoma in Finland from 1971 through 1990: a nationwide study of epidemiology and outcome. Acta Orthop. 2008;79(6):861–866. doi: 10.1080/17453670810016966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.D’Adamo DR. Appraising the current role of chemotherapy for the treatment of sarcoma. Semin Oncol. 2011;38(Suppl 3):S19–S29. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2011.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Asavamongkolkul A, Eckardt JJ, Eilber FR, Dorey FJ, Ward WG, Kelly CM, Wirganowicz PZ, Kabo JM. Endoprosthetic reconstruction for malignant upper extremity tumors. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1999;360:207–220. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199903000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morgan HD, Cizik AM, Leopold SS, Hawkins DS, Conrad EU., 3rd Survival of tumor megaprostheses replacements about the knee. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;450:39–45. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000229330.14029.0d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Palumbo BT, Henderson ER, Groundland JS, Cheong D, Pala E, Letson GD, Ruggieri P. Advances in segmental endoprosthetic reconstruction for extremity tumors: a review of contemporary designs and techniques. Cancer Control. 2011;18(3):160–170. doi: 10.1177/107327481101800303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sharma S, Turcotte RE, Isler MH, Wong C. Experience with cemented large segment endoprostheses for tumors. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007;459:54–59. doi: 10.1097/BLO.0b013e3180514c8e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Unwin PS, Cannon SR, Grimer RJ, Kemp HB, Sneath RS, Walker PS. Aseptic loosening in cemented custom-made prosthetic replacements for bone tumours of the lower limb. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1996;78(1):5–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wirganowicz PZ, Eckardt JJ, Dorey FJ, Eilber FR, Kabo JM. Etiology and results of tumor endoprosthesis revision surgery in 64 patients. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1999;358:64–74. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199901000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Griffin AM, Parsons JA, Davis AM, Bell RS, Wunder JS. Uncemented tumor endoprostheses at the knee: root causes of failure. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005;438:71–79. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000180050.27961.8a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferguson PC, Zdero R, Schemitsch EH, Deheshi BM, Bell RS, Wunder JS. A biomechanical evaluation of press-fit stem constructs for tumor endoprosthetic reconstruction of the distal femur. J Arthroplasty. 2011;26(8):1373–1379. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2010.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Engh CA, Massin P, Suthers KE. Roentgenographic assessment of the biologic fixation of porous-surfaced femoral components. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1990;257:107–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morrey BF, Adams RA, Kessler M. A conservative femoral replacement for total hip arthroplasty. A prospective study. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2000;82(7):952–958. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.82B7.10420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gruen TA, McNeice GM, Amstutz HC. “Modes of failure” of cemented stem-type femoral components: a radiographic analysis of loosening. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1979;141:17–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Henderson ER, Groundland JS, Pala E, Dennis JA, Wooten R, Cheong D, Windhager R, Kotz RI, Mercuri M, Funovics PT, Hornicek FJ, Temple HT, Ruggieri P, Letson GD. Failure mode classification for tumor endoprostheses: retrospective review of five institutions and a literature review. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93(5):418–429. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.J.00834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wunder JS, Leitch K, Griffin AM, Davis AM, Bell RS. Comparison of two methods of reconstruction for primary malignant tumors at the knee: a sequential cohort study. J Surg Oncol. 2001;77(2):89–99. doi: 10.1002/jso.1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]