Abstract

Objective:

Obtaining new details for rotational motion of left ventricular (LV) segments using velocity encoding cardiac MR and correlating the regional motion patterns to LV insertion sites.

Methods:

Cardiac MR examinations were performed on 14 healthy volunteers aged between 19 and 26 years. Peak rotational velocities and circumferential velocity curves were obtained for 16 ventricular segments.

Results:

Reduced peak clockwise velocities of anteroseptal segments (i.e. Segments 2 and 8) and peak counterclockwise velocities of inferoseptal segments (i.e. Segments 3 and 9) were the most prominent findings. The observations can be attributed to the LV insertion sites into the right ventricle, limiting the clockwise rotation of anteroseptal LV segments and the counterclockwise rotation of inferoseptal segments as viewed from the apex. Relatively lower clockwise velocities of Segment 5 and counterclockwise velocities of Segment 6 were also noted, suggesting a cardiac fixation point between these two segments, which is in close proximity to the lateral LV wall.

Conclusion:

Apart from showing different rotational patterns of LV base, mid ventricle and apex, the study showed significant differences in the rotational velocities of individual LV segments. Correlating regional wall motion with known orientation of myocardial aggregates has also provided new insights into the mechanisms of LV rotational motions during a cardiac cycle.

Advances in knowledge:

LV insertion into the right ventricle limits the clockwise rotation of anteroseptal LV segments and the counterclockwise rotation of inferoseptal segments adjacent to the ventricular insertion sites. The pattern should be differentiated from wall motion abnormalities in cardiac pathology.

Assessment of regional rotation patterns of the left ventricular (LV) wall improves the understanding of the systolic and diastolic ventricular function [1]. Cardiac echocardiography with speckle tracking performed in healthy individuals demonstrated large regional differences in the rotation of individual LV segments. For example, significant rotational differences of inferoseptal segments compared with anterolateral segments were reported at the LV base and papillary level [1]. Small regional differences were also recorded at the apical level [1]. Recent developments in cardiac imaging techniques have helped in assessing rotational patterns of LV segments in patients with cardiac pathology. Thus, patients with an atrial septal defect and pulmonary hypertension demonstrated higher average counterclockwise peak rotation of basal LV segments, lower peak rotations of posterior, inferior and posteroseptal walls at the LV base and delayed average interval time of rotational motion [2]. In patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, a reduced cardiac rotation of the posterior region and a reduced radial displacement of the inferior septal zone were recorded [3]. In dog models, occlusion of left anterior descending or left circumflex arteries had a pronounced effect on apex rotation [4]. Under controlled pre-ischaemic conditions, a linear relationship between the apex rotation and the segment length was recorded during ejection and a different steeper relationship during the isovolumic relaxation. In regionally ischaemic segments, this relationship became non-linear for both ejection and isovolumic relaxation [4]. Because the affected myocardial segments may vary depending on the occluded coronary vessel, knowledge about the normal pattern of rotational motion of individual segments becomes increasingly important.

The cause of regional differences in rotational pattern of ventricular segments is likely to be multifactorial and determined by regional ventricular anatomy and dynamics. For example, in a study assessing regional rotational patterns of individual LV segments using speckle tracking echocardiography, Gustafsson et al [1] reported that the diastolic untwist matches the phases of both the E-wave and the A-wave and seems to be related to the intraventricular pressure differences. We hypothesise that the insertion sites of the left ventricle and the cardiac fixation points tethering the heart to the mediastinum in close proximity with the left ventricle may particularly influence the rotational pattern of adjacent LV segments. In the present study, we aimed to correlate the potential differences in rotational velocities of individual LV segments with ventricular insertion sites or major heart vessels located in close proximity with the left ventricle. Considering recent interest in myocardial multilayer measurements, which provide more layer-specific information about the functional state of myocardium at different levels [5–10], separate measurements of rotational myocardial velocities for the inner (endocardial), middle (transmural) and outer (epicardial) layers of the LV wall were performed for 16 ventricular segments.

METHODS AND MATERIALS

Subjects and imaging

Cardiac MR examinations with myocardial velocity encoding were performed on 14 volunteers aged between 19 and 26 years. All subjects were healthy males with no history of smoking or cardiovascular disease. Their baseline characteristics included a heart rate of 57±7 beats per minute [mean ± standard deviation (SD)], systolic blood pressure of 119±8 mmHg, diastolic blood pressure of 75±4 mmHg, LV ejection fraction of 68±6, body mass index of 23.8±2.0 kg m−2.

The cardiac MR scans were performed using a 1.5-T Siemens Sonata clinical scanner (Siemens, Erlangen, Germany). Pilot images, followed by horizontal and vertical long axis cine images were acquired using an steady-state free precession pulse sequence. Cine images for navigator-gated high temporal resolution phase-contrast velocity mapping were acquired using a black blood segmented k-space spoilt gradient echo sequence [11,12] with a temporal resolution of 13.8 ms (repetition time=13.8 ms, echo time=5.0 ms, flip angle=15°, bandwidth=650 Hz per pixel, field of view=400×300 mm, matrix=256×96) [13–16]. Three short axis images were acquired for the LV base, mid ventricle and apex. The basal slice was positioned parallel to the base of the heart and the distal slice to the LV outflow tract. Basal, mid-ventricular and apical slices were positioned 15–20 mm apart, depending on the heart size. With cardiac and respiratory gating, each short axis acquisition took approximately 3–5 min, with an average of 60–70 phases per cardiac cycle. Velocity encoding was performed by including a phase image with no velocity encoding followed by images with a bipolar gradient in the read, phase or slice direction after each radiofrequency pulse to the otherwise identical sequence [velocity encoded gradient echo imaging (venc) in-plane=20 cm s−1, venc through-plane=30 cm s−1]. Post processing was performed in the standard fashion of subtracting the phase from the image with no velocity encoding, followed by conversion of the phase data into velocity maps. The duration of the cardiac cycle was determined by the R–R interval on the electrocardiogram, with end systole defined as the smallest LV cavity [13–16].

Tissue phase mapping (TPM) analysis was performed using customised software (MATLAB®, v. 6.5; MathWorks®, Natick, MA). The endocardial and epicardial borders were manually contoured for the base, mid ventricle and apex for each phase of the cardiac cycle. For the TPM analysis, the left ventricle was divided into 16 segments (6 basal, 6 middle and 4 apical) according to the American Heart Association model [17]. In-plane velocities were transformed into an internal polar coordinate system positioned at the centre of the mass of the left ventricle. Global ventricular velocity time courses for rotational motion of all LV segments were calculated by averaging over the entire segmentation mask, as well as the corresponding peak rotational velocities and time to peak.

Statistical analysis

MATLAB files containing TPM data were converted and generated into Excel™ (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA) files for statistical analysis. Subsequently, all data were analysed using SPSS® v. 16.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) and MedCalc statistical software, v. 12.5.0 (MedCalc Software, Ostend, Belgium). Rotational velocities were expressed as continuous variables and tested for normal distribution. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to test for differences among mean rotational velocities of individual LV segments at the LV base, mid ventricle and LV apex. Before the ANOVA test, Levene's test for equality of variances was performed to ensure that the variables obtained for the compared segments were homogeneous (a standard function of MedCalc software). If the ANOVA test was positive (p<0.05), a Student–Newman–Keuls test was performed to identify sample means that were significantly different from each other. The segments of interest were additionally compared using a post-hoc t-test for independent samples. p-<0.05 was considered to be significant.

RESULTS

Segmental velocities at the left ventricular base

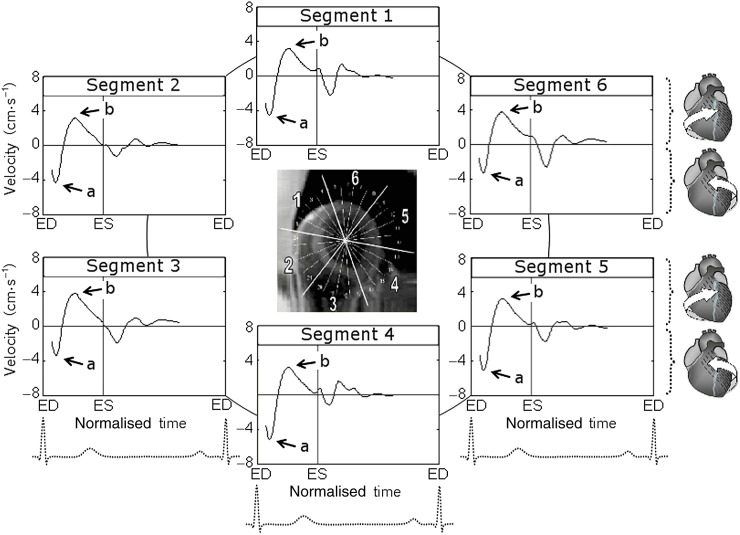

The variation of circumferential velocities during a cardiac cycle for basal LV segments is shown in Figure 1, and a graphical representation of peak clockwise and counterclockwise velocities is shown in Figure 2. Positive values correspond to clockwise rotation of the left ventricle as viewed from the apex, whereas negative values reflect counterclockwise motion. At the commencement of systole, all basal LV segments demonstrated a brief counterclockwise rotation, swiftly reaching peak counterclockwise velocities (Figure 1, wave a). Subsequently, these segments reversed their rotational motion and by mid systole reached peak clockwise velocities (Figure 1, wave b), rotating in a clockwise direction. The velocity of this clockwise rotation gradually decreased during the second half of the systole and after repolarisation. Smaller waves of recoil motion reflecting ventricular untwisting were noted during diastole.

Figure 1.

Circumferential velocity graphs for basal left ventricular (LV) segments during a cardiac cycle. The graphs represent average myocardial velocities for all volunteers. Positive values correspond to clockwise rotation of the left ventricle as viewed from the apex, whereas negative values reflect counterclockwise motion. The arrows show peak counterclockwise (a) and peak clockwise (b) velocities. Segments: 1, basal anterior segment; 2, basal anteroseptal segment; 3, basal inferoseptal segment; 4, basal inferior segment; 5, basal inferolateral segment; and 6, basal anterolateral segment. ED, end diastole; ES, end systole.

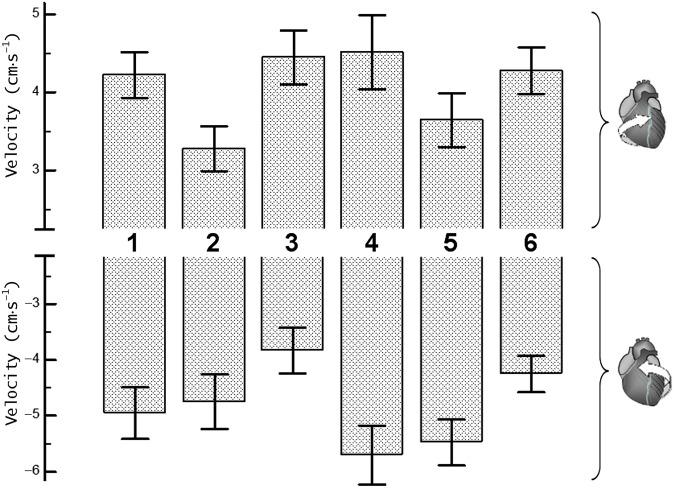

Figure 2.

Peak clockwise and peak counterclockwise velocities for basal left ventricular (LV) segments. The upper panel shows peak clockwise velocities and the lower panel shows peak counterclockwise velocities. Segments: 1, basal anterior segment; 2, basal anteroseptal segment; 3, basal inferoseptal segment; 4, basal inferior segment; 5, basal inferolateral segment; and 6, basal anterolateral segment.

The clockwise rotational velocities of basal LV segments (Segments 1–6, respectively) were 4.0±0.3 [SD ± standard error of the mean (SEM)], 3.2±0.3, 4.6±0.4, 4.5±0.4, 3.7±0.3 and 4.2±0.3 cm s−1 for the inner (endocardial); 4.2±0.3, 3.3±0.3, 4.5±0.3, 4.5±0.3, 3.6±0.3 and 4.3±0.3 cm s−1 for the middle (transmural); and 4.5±0.3, 3.5±0.3, 4.6±0.3, 4.6±0.5, 3.9±0.4 and 4.5±0.3 cm s−1 for the outer (epicardial) layers. The difference between means reached a 5% significance level for the endocardial layer (p=0.034) and a 10% significance level for the transmural layer (p=0.082) (Table 1). Post-hoc Student–Newman–Keuls test showed significant differences of peak clockwise velocities recorded in Segment 2 compared with those recorded in Segments 3 and 4 (p<0.05). These lower clockwise velocities of the basal anteroseptal segment (i.e. Segment 2) were also confirmed by a post-hoc comparison t-test for independent samples, which showed a p-value of 0.007 for endocardial layer, 0.015 for transmural layer and 0.018 for epicardial layer. In addition, the relatively lower clockwise velocity of the basal inferolateral segment (i.e. Segment 5) reached a 10% significance level for endocardial layer (p=0.100) on direct comparison using a t-test for independent samples.

Table 1.

Peak clockwise and counterclockwise velocities for individual left ventricular (LV) segments at the LV base (cm s−1)a

| Velocity | Segment 1 | Segment 2 | Segment 3 | Segment 4 | Segment 5 | Segment 6 | p-value |

| Clockwise velocity | |||||||

| Epicardial | 4.5±0.3 | 3.5±0.3 | 4.6±0.3 | 4.6±0.5 | 3.9±0.4 | 4.5±0.3 | 0.204 |

| Transmural | 4.2±0.3 | 3.3±0.3 | 4.5±0.3 | 4.5±0.5 | 3.6±0.3 | 4.3±0.3 | 0.082 |

| Endocardial | 4.0±0.3 | 3.2±0.3 | 4.6±0.4 | 4.5±0.4 | 3.7±0.3 | 4.2±0.3 | 0.034 |

| Counterclockwise velocity (cm s−1) | |||||||

| Epicardial | −5.5±0.5 | −5.1±0.5 | −3.9±0.3 | −5.8±0.6 | −5.5±0.4 | −4.5±0.3 | 0.056 |

| Transmural | −5.0±0.5 | −4.7±0.5 | −3.8±0.4 | −5.7±0.5 | −5.5±0.4 | −4.3±0.3 | 0.033 |

| Endocardial | −4.5±0.4 | −4.4±0.5 | −3.9±0.4 | −5.6±0.4 | −5.6±0.4 | −4.1±0.3 | 0.019 |

One-way analysis of variance was used to test for differences among means (values are mean ± standard error of mean).

The counterclockwise rotational velocities of basal LV segments (Segments 1–6, respectively) were −4.5±0.4 (SD±SEM), −4.4±0.5, −3.9±0.4, −5.6±0.4, −5.6±0.4, −4.1±0.3 cm s−1 for inner (endocardial); −5.0±0.5, −4.7±0.5, −3.8±0.4, −5.7±0.5, −5.5±0.4, −4.3±0.3 cm s−1 for middle (transmural); and −5.5±0.5, −5.1±0.5, −3.9±0.3, −5.8±0.6, −5.5±0.4, −4.5±0.3 cm s−1 for outer (epicardial) layers. The difference between means reached a 5% significance level for endocardial (p=0.019) and transmural (p=0.033) layers and a 10% significance level for epicardial layer (p=0.056) (Table 1). Post-hoc Student–Newman–Keuls test showed significant differences between peak counterclockwise velocities recorded in Segments 3 and 4 (p<0.05). The lower counterclockwise velocities of the basal inferoseptal segment (i.e. Segment 3) were also confirmed by a post-hoc comparison t-test for independent samples (p<0.05 for all layers). In addition, the lower counterclockwise velocities of basal anterolateral segment (i.e. Segment 6) reached a 5% significance level for endocardial and transmural layers (p<0.05) and a 10% significance level for epicardial layer (p<0.10) when directly compared with counterclockwise velocities of adjacent Segments 5 and 4 using a t-test for independent samples.

Segmental velocities at mid ventricle

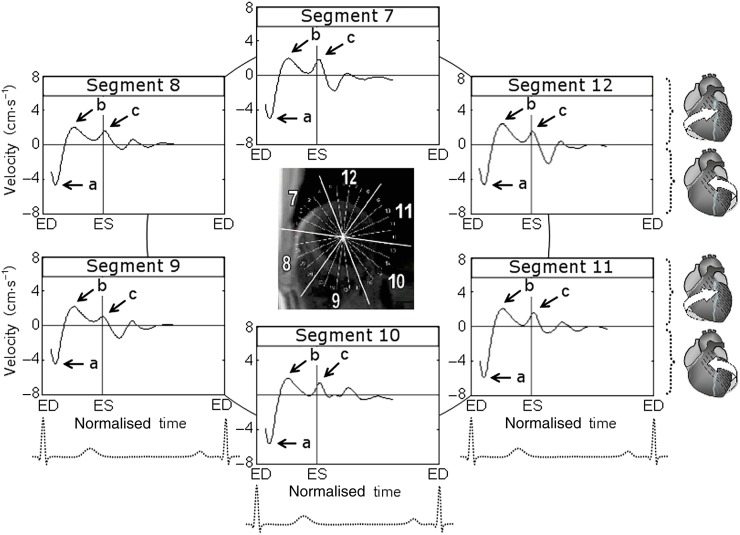

The rotational velocity graphs for mid-ventricular segments during a cardiac cycle are shown in Figure 3, whereas the graphical representation of peak clockwise and counterclockwise velocities is shown in Figure 4. Positive values correspond to the clockwise rotation of the left ventricle as viewed from the apex, whereas negative values reflect counterclockwise motion. At the commencement of systole, all mid-ventricular segments demonstrated a brief counterclockwise rotation, swiftly reaching peak counterclockwise velocities in synchrony with basal and apical segments (Figure 3, wave a). Subsequently, mid-ventricular segments reversed their rotational motion and by mid systole reached peak clockwise velocities (Figure 3, wave b), rotating in a clockwise direction in synchrony with basal LV segments. However, the amplitude of this wave was lower than that recorded at the LV base. A second wave of clockwise rotation was noted after repolarisation (Figure 3, wave c), reflecting ventricular untwisting. This wave was in synchrony with a similar wave recorded at the LV apex (Figure 5, wave b), although it had a lower amplitude at mid ventricle.

Figure 3.

Circumferential velocity graphs for mid-left ventricular (LV) segments during a cardiac cycle. The graphs represent the average myocardial velocities for all volunteers. Positive values correspond to clockwise rotation of the left ventricle as viewed from the apex, whereas negative values reflect counterclockwise motion. The arrows (a) and (b) show peak counterclockwise and peak clockwise velocities, respectively. The arrow (c) points towards a smaller wave of clockwise velocity after repolarisation during ventricular untwisting. Segments: 7, mid-anterior segment; 8, mid-anteroseptal segment; 9, mid-inferoseptal segment; 10, mid-inferior segment; 11, mid-inferolateral segment; and 12, mid-anterolateral segment. ED, end diastole; ES, end systole.

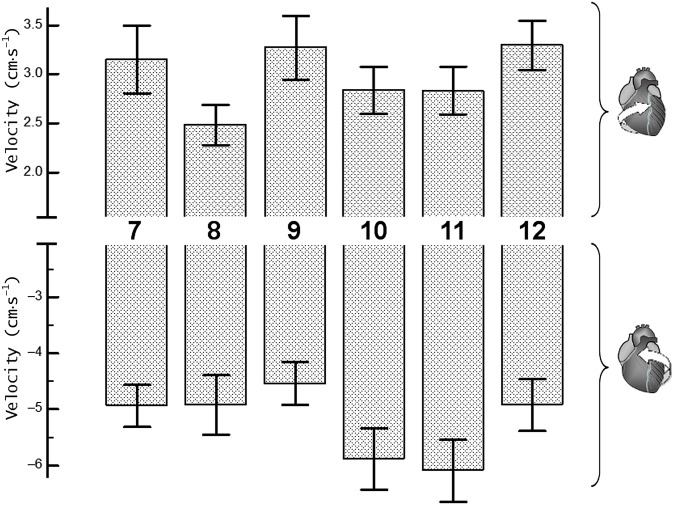

Figure 4.

Peak clockwise and peak counterclockwise velocities for left ventricular (LV) segments at mid-ventricular level. The upper panel shows peak clockwise velocities and the lower panel shows peak counterclockwise velocities. Segments: 7, mid-anterior segment; 8, mid-anteroseptal segment; 9, mid inferoseptal segment; 10, mid-inferior segment; 11, mid-inferolateral segment; and 12, mid-anterolateral segment.

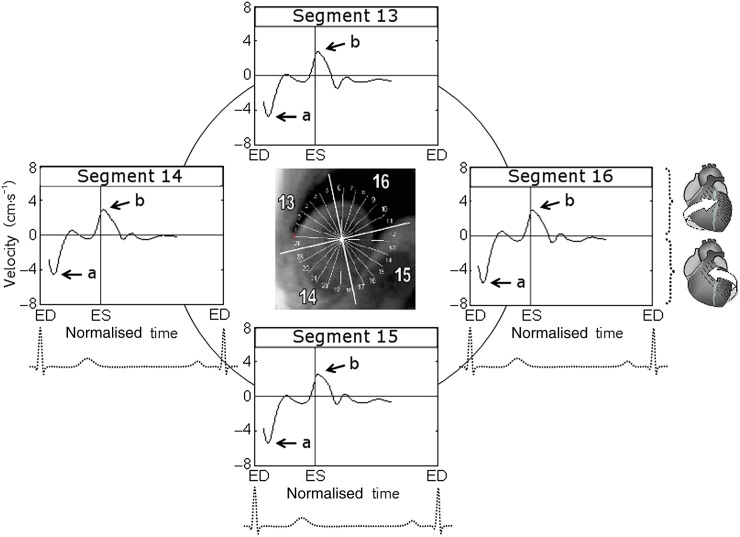

Figure 5.

Circumferential velocity graphs for apical left ventricular (LV) segments during a cardiac cycle. The graphs represent the average myocardial velocities for all volunteers. Positive values correspond to clockwise rotation of the left ventricle as viewed from the apex, whereas negative values reflect counterclockwise motion. The arrows show peak counterclockwise (a) and peak clockwise (b) velocities. Segments: 13, apical anterior segment; 14, apical septal segment; 15, apical inferior segment; and 16, apical lateral segment. ED, end diastole; ES, end systole.

The peak clockwise velocities of mid-LV segments (Segments 7–12, respectively) were 2.9±0.3 (SD±SEM), 2.4±0.2, 3.5±0.4, 3.0±0.2, 2.9±0.2, 3.2±0.2 cm s−1 for inner (endocardial); 3.2±0.3, 2.5±0.2, 3.3±0.3, 2.8±0.2, 2.8±0.2, 3.3±0.3 cm s−1 for middle (transmural); and 3.6±0.4, 2.8±0.3, 3.5±0.4, 2.9±0.3, 3.1±0.3, 3.7±0.3 cm s−1 for outer (epicardial) layers. Similar to the LV base findings, lower clockwise velocities were recorded for anteroseptal segment (i.e. Segment 8), although the difference between means estimated by one-way ANOVA did not reach statistical significance at mid ventricle (Table 2). Comparison t-tests for independent samples performed between clockwise velocities of individual LV segments, however, showed significant differences between Segments 8 and 12 (p<0.05 for all three layers), Segments 8 and 9 (p=0.012 for endocardial layer and 0.051 for transmural layer) and Segments 8 and 7 (p=0.075 for endocardial layer).

Table 2.

Peak clockwise and counterclockwise velocities for individual left ventricular segments at mid-ventricular levela

| Velocity | Segment 7 | Segment 8 | Segment 9 | Segment 10 | Segment 11 | Segment 12 | p-value |

| Clockwise velocity | |||||||

| Epicardial | 3.6±0.4 | 2.8±0.3 | 3.5±0.4 | 2.9±0.3 | 3.1±0.3 | 3.7±0.3 | 0.222 |

| Transmural | 3.2±0.3 | 2.5±0.2 | 3.3±0.3 | 2.8±0.2 | 2.8±0.2 | 3.3±0.3 | 0.250 |

| Endocardial | 2.9±0.3 | 2.4±0.2 | 3.5±0.4 | 3.0±0.2 | 2.9±0.2 | 3.2±0.2 | 0.125 |

| Counterclockwise velocity (cm s−1) | |||||||

| Epicardial | −5.3±0.4 | −5.2±0.6 | −4.5±0.4 | −6.3±0.6 | −6.4±0.6 | −5.0±0.5 | 0.089 |

| Transmural | −4.9±0.4 | −4.9±0.5 | −4.5±0.4 | −5.9±0.5 | −6.1±0.6 | −4.9±0.5 | 0.152 |

| Endocardial | −4.6±0.3 | −4.7±0.4 | −4.6±0.3 | −5.6±0.6 | −5.7±0.5 | −4.9±0.5 | 0.238 |

One-way analysis of variance was used to test for differences among means (values are mean ± standard error of mean).

The peak counterclockwise velocities of mid-LV segments (Segments 7–12, respectively) were −4.6±0.3 (SD±SEM), −4.7±0.4, −4.6±0.3, −5.6±0.6, −5.7±0.5, −4.9±0.5 cm s−1 for inner (endocardial); −4.9±0.4, −4.9±0.5, −4.5±0.4, −5.9±0.5, −6.1±0.6, −4.9±0.5 cm s−1 for middle (transmural); and −5.3±0.4, −5.2±0.6, −4.5±0.4, −6.3±0.6, −6.4±0.6, −5.0±0.5 cm s−1 for outer (epicardial) layers. Lower counterclockwise velocities were again noted for the inferoseptal segment (i.e. Segment 9), although one-way ANOVA showed a 10% significance level for epicardial layer only (p=0.089, Table 2). Comparison t-tests for independent samples, however, showed significant differences between Segments 9 and 11 (p=0.015 for epicardial, p=0.030 for transmural and p=0.079 for endocardial layers) and between Segments 9 and 10 (p=0.016 for epicardial and p=0.053 for transmural layers).

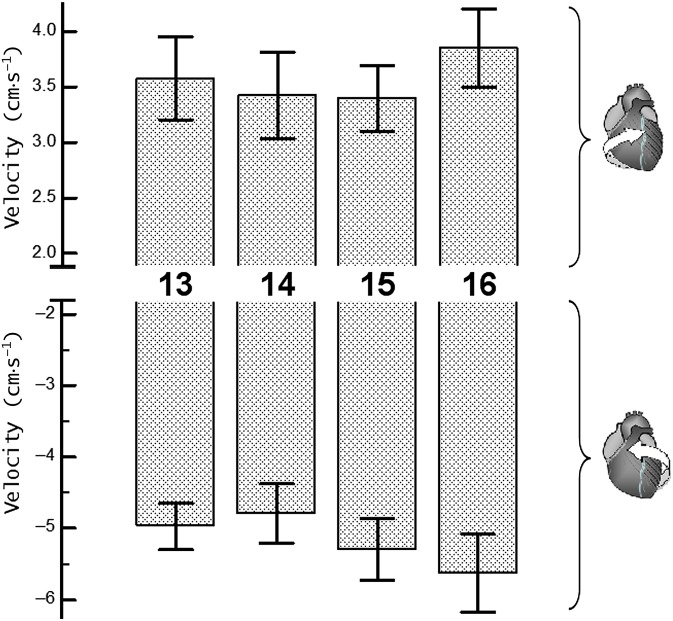

Segmental velocities at the left ventricular apex

The variation of circumferential velocities during a cardiac cycle for apical LV segments is shown in Figure 5, and the graphical representation of peak clockwise and counterclockwise velocities is shown in Figure 6. At the commencement of systole, all apical LV segments rotated in a counterclockwise direction, swiftly reaching peak counterclockwise velocities (Figure 5, wave a); after this the velocity of counterclockwise rotation gradually decreased. After repolarisation, the apical segments reversed their rotational motion, demonstrating a prominent recoil wave of clockwise rotation consistent with the ventricular untwisting (Figure 5, wave b). The peak clockwise velocities for apical LV segments (Segments 13–16, respectively) were 3.5±0.3 (SD±SEM), 3.4±0.4, 3.5±0.4, 4.1±0.4 cm s−1 for inner (endocardial); 3.6±0.4, 3.4±0.4, 3.4±0.3, 3.8±0.4 cm s−1 for middle (transmural); and 3.7±0.4, 3.5±0.3, 3.5±0.3, 3.7±0.4 cm s−1 for outer (epicardial) layers. Of note, these peak clockwise velocities for apical LV segments were represented by a recoil wave of ventricular untwisting after repolarisation (Figure 5, wave b), while the peak clockwise velocities for basal LV segments were represented by a wave of clockwise rotation during ventricular twisting (Figure 1, wave b).

Figure 6.

Peak clockwise and peak counterclockwise velocities for apical left ventricular (LV) segments. The upper panel shows peak clockwise velocities and the lower panel shows peak counterclockwise velocities. Segments: 13, apical anterior segment; 14, apical septal segment; 15, apical inferior segment; 16, apical lateral segment.

The peak counterclockwise velocities for apical LV segments (Segments 13–16, respectively) were −4.8±0.4 (SD±SEM), −4.4±0.4, −4.9±0.5, −5.3±0.6 cm s−1 for inner (endocardial); −5.0±0.3, −4.8±0.4, −5.3±0.4, −5.6±0.5 cm s−1 for middle (transmural); and −5.2±0.3, −5.3±0.5, −5.7±0.4, −5.9±0.5 cm s−1 for outer (epicardial) layers (Table 3). The slightly higher clockwise and counterclockwise velocities of the apical lateral segment (i.e. Segment 16) did not reach statistical significance on one-way ANOVA or comparison t-tests performed between individual LV segments.

Table 3.

Peak clockwise and counterclockwise velocities for individual left ventricular (LV) segments at the LV apexa

| Velocity | Segment 13 | Segment 14 | Segment 15 | Segment 16 | p-value |

| Clockwise velocity | |||||

| Epicardial | 3.7±0.4 | 3.5±0.3 | 3.5±0.3 | 3.7±0.4 | 0.949 |

| Transmural | 3.6±0.4 | 3.4±0.4 | 3.4±0.3 | 3.8±0.4 | 0.796 |

| Endocardial | 3.5±0.3 | 3.4±0.4 | 3.5±0.4 | 4.1±0.4 | 0.535 |

| Counterclockwise velocity (cm s−1) | |||||

| Epicardial | −5.2±0.3 | −5.3±0.5 | −5.7±0.4 | −5.9±0.5 | 0.567 |

| Transmural | −5.0±0.3 | −4.8±0.4 | −5.3±0.4 | −5.6±0.5 | 0.544 |

| Endocardial | −4.8±0.4 | −4.4±0.4 | −4.9±0.5 | −5.3±0.6 | 0.593 |

One-way analysis of variance was used to test for differences among means (values are mean ± standard error of mean).

DISCUSSION

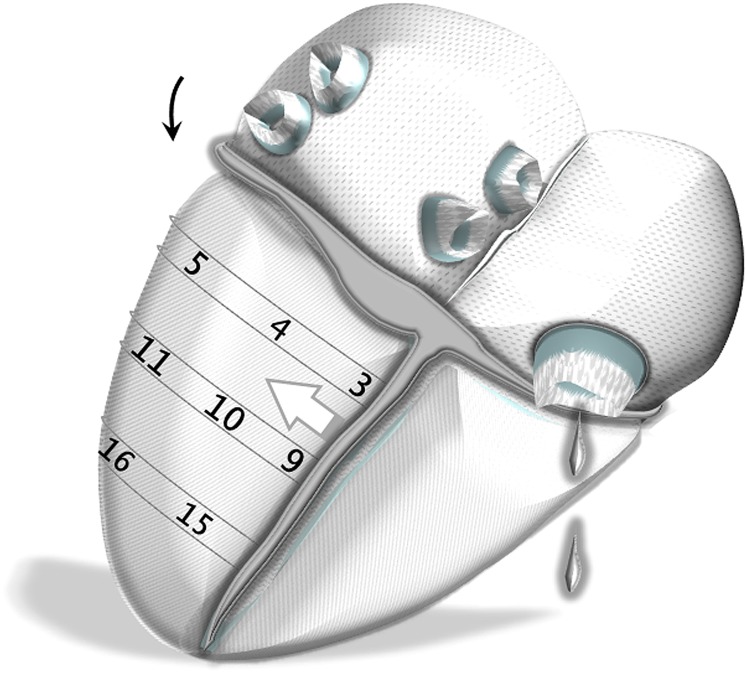

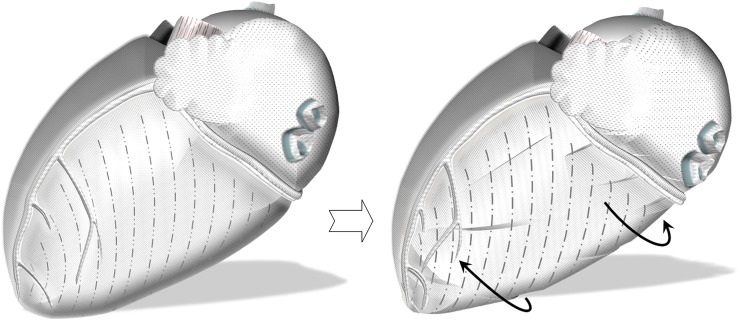

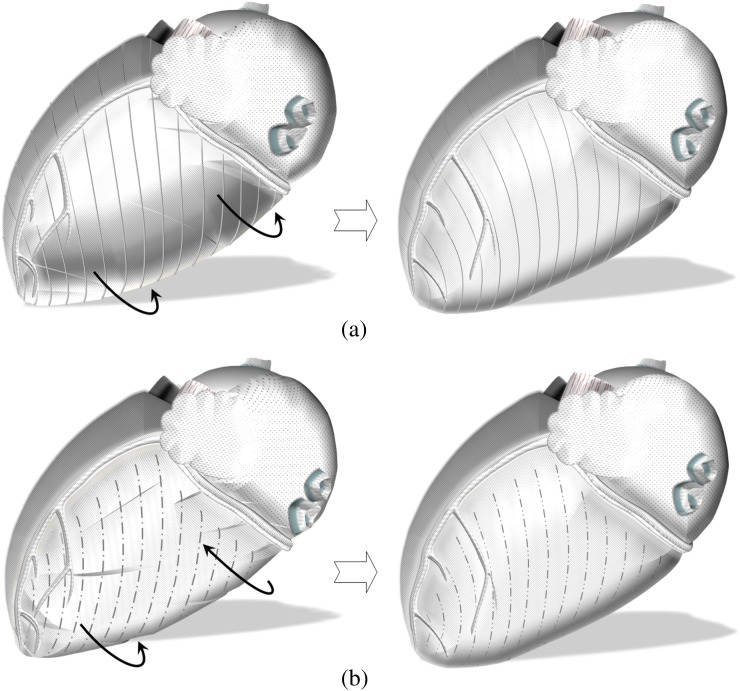

In this study, we have described in detail the particularities of rotational motion of LV segments during a cardiac cycle. Apart from showing different rotational patterns of LV base, mid ventricle and apex, the study also demonstrated significant differences between rotational velocities of individual LV segments within the same axial slice. Although the cause of regional differences in rotational pattern of ventricular segments is likely to be multifactorial, we tried to relate many of our findings to the ventricular insertion sites and anatomical orientation of cardiomyocytes within the ventricular wall. For example, on the anterior cardiac surface, the LV insertion into the right ventricle is likely to affect the clockwise rotation of anteroseptal segments, limiting the velocity of the motion away from the insertion site (Figure 7). This can explain the lower peak clockwise velocities of anteroseptal segments recorded at the LV base (Segment 2) and mid ventricle (Segment 8). On the posterior cardiac surface, the LV insertion into the right ventricle is likely to affect the counterclockwise rotation of inferoseptal segments similarly by limiting the velocity of the motion away from the insertion site (Figure 8). This can explain the lower peak counterclockwise velocities of inferoseptal segments (i.e. Segments 3 and 9).

Figure 7.

Schematic representation of left ventricular (LV) segments on the left lateral heart surface. Anteriorly, the LV insertion into the right ventricle is likely to affect the clockwise rotation of anteroseptal segments (white arrow). This can explain the lower peak clockwise velocities of Segments 2 and 8. Segments: 1, basal anterior segment; 2, basal anteroseptal segment; 5, basal inferolateral segment; 6, basal anterolateral segment; 7, mid-anterior segment; 8, mid-anteroseptal segment; 11, mid-inferolateral segment; 12, mid-anterolateral segment; 13, apical anterior segment; and 16, apical lateral segment.

Figure 8.

Schematic representation of LV segments on the posterior heart surface. Posteriorly, the left ventricular (LV) insertion into the right ventricle is likely to affect the counterclockwise rotation of inferoseptal segments (white arrow). This can explain the lower peak counterclockwise velocities of Segments 3 and 9. In addition, the relatively lower clockwise velocity of Segment 5 in association with lower counterclockwise velocity of Segment 6 is rather suggestive of a cardiac fixation point between these two segments (curved black arrow), limiting the velocity of the motion away from this point. Potential causes might be supporting structures connecting the basal part of the left ventricle to the annulus (i.e. basal or tertiary cords), which are found in significant numbers in this region beneath the posterior leaflet of the mitral valve. Segments: 3, basal inferoseptal segment; 4, basal inferior segment; 5, basal inferolateral segment; 9, mid-inferoseptal segment; 10, mid-inferior segment; 11, mid-inferolateral segment; 15, apical inferior segment; and 16, apical lateral segment.

In addition, the relatively lower clockwise velocity of Segment 5 in association with lower counterclockwise velocity of Segment 6 (differences reaching a 5% and 10% significance level on independent samples t-tests) is rather suggestive of a cardiac fixation site between these two segments (Figure 8). Such a fixation point in close proximity to the left lateral ventricular wall would explain the lower peak clockwise velocity of Segment 5 (limited velocity of motion away from the insertion point) and lower counterclockwise velocity of Segment 6 (also limited velocity of motion away from the insertion point). Potential causes to be considered include the supporting structures connecting the basal part of the left ventricle to the annulus, the so-called “basal cords”, which are known to be important structures and are left intact, for instance, during mitral valve replacements for this reason [18–22]. The tertiary cords, in particular, arise directly from the LV wall or from the trabeculae carnae and insert exclusively into the posterior mitral leaflet [18]. These short fibrous connections, which are only found in significant numbers beneath the posterior leaflet of the mitral valve, may form such a “fixation” site, slightly limiting the rotational motion of adjacent ventricular wall away from this point. However, further studies would be required to confirm this hypothesis. An alternative explanation might be related to the muscular connections between the two papillary muscle groups or between the sides of the papillary muscles and the LV myocardium in proximity to the lateral LV wall. However, a potential limitation of regional LV rotation caused by a papillary muscle is expected to be more pronounced at the mid ventricle rather than at the LV base (closer to the insertion point of the structure causing the limitation), which contradicts our findings.

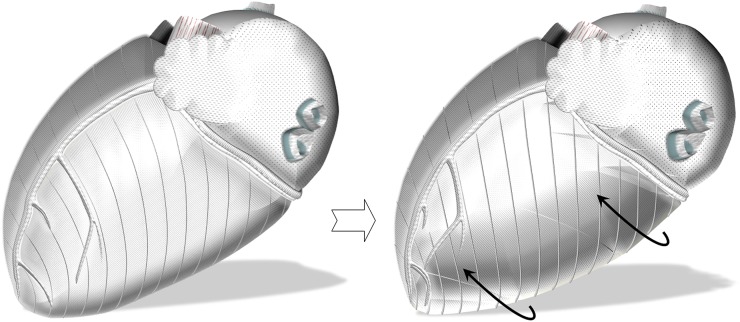

The LV base insertion at the fibrous annulus also plays a major role in LV twisting. In a previous study, we related the rotational LV motion to the anatomical orientation of cardiomyocytes within the left ventricle [13]. The outer-surface aggregates extend across a larger surface, having a greater radius of curvature and greater moment of torque. As such, they are likely to dominate the direction of circumferential motion [13,23]. A significant portion of the outer-surface aggregates extend across the anterior interventricular sulcus, extending to the right ventricle, great vessels and fibrous structures (Figure 9). These aggregates have been described during manual dissections and recently using diffusion tensor MRI [24,25]. Having the longest extension at the anterior heart surface, they are likely to determine the dominant direction of initial ventricular rotation, causing the entire left ventricle to rotate in a counterclockwise direction at the beginning of systole [13]. Because the LV base is fixed in the fibrous annulus (by fibrous ligaments, great vessels etc.), the apex continues its counterclockwise rotation during the entire systole, resulting in twisting (Figure 9). Considering that LV base insertion at the fibrous annulus is accomplished by fibrous and elastic structures, some rotational motion for a limited range is still possible, which can explain the brief counterclockwise rotation of the LV base recorded at the commencement of systole in synchrony with the rest of the ventricle. However, as the range of rotational motion close to the LV base insertion line is limited, the initial counterclockwise rotation of the LV base swiftly comes to an end, facilitating LV twisting (Figure 9). Of note, our axial slice of the LV base was chosen at some distance from the actual LV base insertion line to exclude the interference of LV outflow tract with myocardial wall velocity measurements. Surely, contraction of other cardiomyocytes and myocardial layers further augments LV twisting and also contributes to the clockwise rotation of the LV base. For example, contraction of the outer-surface aggregates with their extension limited to the LV wall is expected to cause a rotational motion of the ventricular apex and base against each other, i.e. a clockwise rotation of the LV base and a further augmentation of counterclockwise motion of the LV apex (Figure 10). Because these aggregates are shorter, net motion only becomes apparent after the initial counterclockwise rotation of the entire left ventricle [13], which is dominated by the longer aggregates extending to the right ventricle, great vessels and fibrous structures.

Figure 9.

Schematic representation of the outer-surface myocardial aggregates extending to the right ventricle, great vessels and fibrous structures. Having the longest extension onto the anterior heart surface, a greater radius of curvature and greater moment of torque, they are likely to determine the dominant direction of initial ventricular rotation [13,23], causing the entire left ventricle to rotate in a counterclockwise direction as viewed from the apex (curved black arrows). As the range of rotational motion close to the left ventricular (LV) base insertion line is limited, the initial countercklockwise rotation of the LV base in synchrony with the rest of the ventricle swiftly comes to an end, facilitating LV twisting.

Figure 10.

Schematic representation of the outer-surface myocardial aggregates with their extension limited to the left ventricular (LV) wall. Having a spiral orientation, they are expected to cause a rotational motion of the LV apex and base against each other (i.e. a clockwise rotation of the LV base and a counterclockwise rotation of the apex as shown by the curved black arrows), resulting in ventricular twisting. Because these aggregates are shorter, net motion only becomes apparent after the initial counterclockwise rotation of the entire left ventricle [13], which is dominated by the longer aggregates described in Figure 9.

Correlation of rotational motions of the left ventricle with the anatomical orientation of cardiomyocytes can also explain the rotational patterns of basal and apical segments noted after repolarisation (T wave on electrocardiograph). Repolarisation leads to cessation of active myocardial contraction and cardiomyocyte relaxation [26]. Hence, subsequent counter-rotational movement would be expected. However, a sudden change in the direction of movement immediately after repolarisation occurred only at the apex, while the circumferential velocity curves of basal LV segments showed gradual deceleration of their clockwise rotation. This phenomenon can be explained by considering the relaxation properties of the myocyte aggregates. The relaxation of the outer-surface aggregates extending outside the left ventricle is expected to result in a clockwise rotation of the entire left ventricle, which is opposed to systolic motion (Figure 11). Relaxation of the outer-surface aggregates that are limited to the LV wall is expected to result in a clockwise rotation of the LV apex and a counter-clockwise rotation of the LV base (ventricular untwisting). The net result for the apical segments is a clockwise rotation of the ventricular apex (relaxation of myocyte aggregates limited to LV wall) superimposed on a clockwise rotation of the entire left ventricle (relaxation of myocyte aggregates extending to the anterior heart surface and fibrous annulus). Considering that LV apex is a smaller free end engaged in a twisting motion with a larger LV base, the overall result is a sudden clockwise rotation of apical segments. In our study, this was seen as a prominent wave of clockwise rotation on circumferential velocity curves of apical segments (Figure 5, wave b), promptly following repolarisation. The net result for basal segments after repolarisation was a counterclockwise rotation of the LV base (relaxation of myocyte aggregates limited to LV wall) superimposed on a clockwise rotation of the entire left ventricle (relaxation of myocyte aggregates extending to the anterior heart surface and fibrous annulus) (Figure 11). Because the motions counteracted each other, no abrupt changes were noted on circumferential velocity graphs of basal segments, which demonstrated continuing deceleration of their clockwise rotation immediately after repolarisation and a subsequent smaller wave of recoil counterclockwise motion in diastole (Figure 1).

Figure 11.

Counterrotational motions after repolarisation. The relaxation of the outer-surface aggregates extending outside the left ventricle is expected to result in a clockwise rotation of the entire left ventricle, which is opposite to the systolic motion (a, curved black arrows). Relaxation of the outer-surface aggregates that are limited to the left ventricular (LV) wall is expected to result in a clockwise rotation of the apex and a counterclockwise rotation of the base (b, curved black arrows). The net result for the apical segments was a sudden change in rotational motion, which reflected in a prominent wave of clockwise rotation on velocity graphs (Figure 5, wave b). On the LV base, however, the motions counteracted each other—the velocity graphs showing gradual deceleration of the clockwise rotation immediately after repolarisation and a subsequent smaller wave of recoil counterclockwise motion in diastole (Figure 1).

Study limitations and perspectives

All patients included in this study were young healthy males. The end systole was calculated and normalised for the entire group based on the smallest LV cavity and not on the timing of the closure and opening of the cardiac valves, which was not recorded. The end systole is provided for general orientation and even when slightly displaced would not affect data interpretation.

The proposed concepts provide an explanation of rotational motion of the left ventricle based on the predominant orientation of outer layer myocardial aggregates that have the longest extension and are expected to dominate the direction of movement. Contraction of other myocardial aggregates can also facilitate or counteract these rotational motions depending on their orientation. In addition, there is a certain variation of the helix angle (between the fibre orientation and a short axial line) and the transverse angle (between the fibre orientation and a long axial line) for different LV layers and myocardial aggregates [27], further affecting the dynamics of motion. Recent advances in diffusion tensor MRI have opened up new perspectives in this area, and developments of statistical atlases of the human cardiac fibre architecture are currently underway [25,27]. This may provide an excellent foreground for new studies correlating rotational LV motions with precise orientation of myocardial aggregates at the ventricular wall.

CONCLUSIONS

Apart from showing different rotational patterns of LV base, mid-ventricle and apex, the study demonstrated significant differences between rotational velocities of individual LV segments. Reduced peak clockwise velocities of anteroseptal segments and counterclockwise velocities of inferoseptal segments can be attributed to the LV insertion sites into the right ventricle. Relatively lower clockwise velocities of Segment 5 and counterclockwise velocities of Segment 6 are rather suggestive of a cardiac fixation point between these two segments in close proximity with the lateral LV wall. Correlating segmental rotational patterns with known orientation of myocardial aggregates has also provided new insights into the mechanisms of LV rotational motions during a cardiac cycle.

FUNDING

This research was funded by the British Heart Foundation and Oxford Partnership Comprehensive Biomedical Research Centre.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gustafsson U, Lindqvist P, Morner S, Waldenstrom A. Assessment of regional rotation patterns improves the understanding of the systolic and diastolic left ventricular function: an echocardiographic speckle-tracking study in healthy individuals. Eur J Echocardiogr 2009;10:56–61 10.1093/ejechocard/jen141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Song J, Li C, Tong C, Yang H, Yang X, Zhang J, et al. Evaluation of left ventricular rotation and twist using speckle tracking imaging in patients with atrial septal defect. J Huazhong Univ Sci Technolog Med Sci. 2008;28:190–3 10.1007/s11596-008-0219-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maier SE, Fischer SE, McKinnon GC, Hess OM, Krayenbuehl HP, Boesiger P. Evaluation of left ventricular segmental wall motion in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with myocardial tagging. Circulation 1992;86:1919–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kroeker CA, Tyberg JV, Beyar R. Effects of ischemia on left ventricular apex rotation. An experimental study in anesthetized dogs. Circulation 1995;92:3539–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davidsen ES, Moen CA, Matre K. Radial deformation by tissue Doppler imaging in multiple myocardial layers. Scand Cardiovasc J 2010;44:82–91 10.1080/14017430903177708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rosner A, How OJ, Aarsaether E, Stenberg TA, Andreasen T, Kondratiev TV, et al. High resolution speckle tracking dobutamine stress echocardiography reveals heterogeneous responses in different myocardial layers: implication for viability assessments. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2010;23:439–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Matre K, Moen CA, Fannelop T, Dahle GO, Grong K. Multilayer radial systolic strain can identify subendocardial ischemia: an experimental tissue Doppler imaging study of the porcine left ventricular wall. Eur J Echocardiogr 2007;8:420–30 10.1016/j.euje.2007.03.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moen CA, Salminen PR, Grong K, Matre K. Left ventricular strain, rotation, and torsion as markers of acute myocardial ischemia. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2011;300:H2142–54 10.1152/ajpheart.01012.2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Becker M, Ocklenburg C, Altiok E, Futing A, Balzer J, Krombach G, et al. Impact of infarct transmurality on layer-specific impairment of myocardial function: a myocardial deformation imaging study. Eur Heart J 2009;30:1467–76 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bachner-Hinenzon N, Ertracht O, Leitman M, Vered Z, Shimoni S, Beeri R, et al. Layer-specific strain analysis by speckle tracking echocardiography reveals differences in left ventricular function between rats and humans. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2010;299:H664–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jung B, Föll D, Böttler P, Petersen S, Hennig J, Markl M. Detailed analysis of myocardial motion in volunteers and patients using high-temporal-resolution MR tissue phase mapping. J Magn Reson Imaging 2006;24:1033–9 10.1002/jmri.20703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jung B, Markl M, Foll D, Hennig J. Investigating myocardial motion by MRI using tissue phase mapping. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2006;29(Suppl. 1):S150–7 10.1016/j.ejcts.2006.02.066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Codreanu I, Robson MD, Golding SJ, Jung BA, Clarke K, Holloway CJ. Longitudinally and circumferentially directed movements of the left ventricle studied by cardiovascular magnetic resonance phase contrast velocity mapping. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 2010;12:48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Codreanu I, Robson MD, Rider OJ, Pegg TJ, Jung BA, Dasanu CA, et al. Chasing the reflected wave back into the heart: a new hypothesis while the jury is still out. Vasc Health Risk Manag 2011;7:365–73 10.2147/VHRM.S20845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Codreanu I, Pegg TJ, Selvanayagam JB, Robson MD, Rider OJ, Dasanu CA, et al. Details of left ventricular remodeling and the mechanism of paradoxical ventricular septal motion after coronary artery bypass graft surgery. J Invasive Cardiol 2011;23:276–82 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Codreanu I, Pegg TJ, Selvanayagam JB, Robson MD, Rider OJ, Dasanu CA, et al. Normal values of regional and global myocardial wall motion in young and elderly individuals using navigator gated tissue phase mapping. Age (Dordr) Apr 2013. Epub ahead of print 10.1007/s11357-013-9535-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Cerqueira MD, Weissman NJ, Dilsizian V, Jacobs AK, Kaul S, Laskey WK, et al. Standardized myocardial segmentation and nomenclature for tomographic imaging of the heart: a statement for healthcare professionals from the Cardiac Imaging Committee of the Council on Clinical Cardiology of the American Heart Association. Circulation 2002;105:539–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Silbiger JJ, Bazaz R. Contemporary insights into the functional anatomy of the mitral valve. Am Heart J 2009;158:887–95 10.1016/j.ahj.2009.10.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Obadia JF, Casali C, Chassignolle JF, Janier M. Mitral subvalvular apparatus: different functions of primary and secondary chordae. Circulation 1997;96:3124–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rodriguez F, Langer F, Harrington KB, Tibayan FA, Zasio MK, Cheng A, et al. Importance of mitral valve second-order chordae for left ventricular geometry, wall thickening mechanics, and global systolic function. Circulation 2004;110(11 Suppl. 1):II115–22 10.1161/01.CIR.0000138580.57971.b4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Timek TA, Lai DT, Dagum P, Tibayan F, Daughters GT, Liang D, et al. Ablation of mitral annular and leaflet muscle: effects on annular and leaflet dynamics. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2003;285:H1668–74 10.1152/ajpheart.00179.2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Natsuaki M, Itoh T, Tomita S, Furukawa K, Yoshikai M, Suda H, et al. Importance of preserving the mitral subvalvular apparatus in mitral valve replacement. Ann Thorac Surg 1996;61:585–90 10.1016/0003-4975(95)01058-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Taber LA, Yang M, Podszus WW. Mechanics of ventricular torsion. J Biomech 1996;29:745–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Greenbaum RA, Ho SY, Gibson DG, Becker AE, Anderson RH. Left ventricular fibre architecture in man. Br Heart J 1981;45:248–63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rohmer D, Sitek A, Gullberg GT. Reconstruction and visualization of fiber and laminar structure in the normal human heart from ex vivo diffusion tensor magnetic resonance imaging (DTMRI) data. Invest Radiol 2007;42:777–89 10.1097/RLI.0b013e3181238330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Klabunde RE. Cardiovascular physiology concepts. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005. Chapter 4 65 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lombaert H, Peyrat JM, Croisille P, Rapacchi S, Fanton L, Cheriet F, et al. Human atlas of the cardiac fiber architecture: study on a healthy population. IEEE Trans Med Imaging 2012;31:1436–47 10.1109/TMI.2012.2192743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]