Abstract

Postprandial lipemia is characterized by a transient increase in circulating triglyceride-rich lipoproteins such as very low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) and has been shown to activate monocytes in vivo. Lipolysis of VLDL releases remnant particles, phospholipids, monoglycerides, diglycerides, and fatty acids in close proximity to endothelial cells and monocytes. We hypothesized that postprandial VLDL lipolysis products could activate and recruit monocytes by increasing monocyte expression of proinflammatory cytokines and adhesion molecules, and that such activation is related to the development of lipid droplets. Freshly isolated human monocytes were treated with VLDL lipolysis products (2.28 mmol/l triglycerides + 2 U/ml lipoprotein lipase), and monocyte adhesion to a primed endothelial monolayer was observed using a parallel plate flow chamber coupled with a CCD camera. Treated monocytes showed more rolling and adhesion than controls, and an increase in transmigration between endothelial cells. The increased adhesive events were related to elevated expression of key integrin complexes including Mac-1 [αm-integrin (CD11b)/β2-integrin (CD18)], CR4 [αx-integrin (CD11c)/CD18] and VLA-4 [α4-integrin (CD49d)/β1-integrin (CD29)] on treated monocytes. Treatment of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) and THP-1 monocytes with VLDL lipolysis products increased expression of TNFα, IL-1β, and IL-8 over controls, with concurrent activation of NFkB and AP-1. NFκB and AP-1-induced cytokine and integrin expression was dependent on ERK and Akt phosphorylation. Additionally, fatty acids from VLDL lipolysis products induced ERK2-dependent lipid droplet formation in monocytes, suggesting a link to inflammatory signaling pathways. These results provide novel mechanisms for postprandial monocyte activation by VLDL lipolysis products, suggesting new pathways and biomarkers for chronic, intermittent vascular injury.

Keywords: adhesion molecules, fatty acids, inflammation, lipoprotein lipase

a key step in the development of atherosclerosis is the activation and recruitment of circulating monocytes to sites of endothelial damage (10, 28, 30). Monocytes in the blood can be activated under physiological and pathophysiological conditions, such as hypertriglyceridemia (2, 39), contributing to their endothelial recruitment. However, little is known about the specific mechanisms by which monocytes become activated and adhere to endothelium in the postprandial state, nor how the accumulation of lipid droplets relates to such activation (6, 11). A previous study in our lab showed that postprandial hypertriglyceridemia increases the expression of TNFα and IL-1β by circulating monocytes (16). Our goal in this study was to determine whether monocytes can become activated independently of the endothelium by lipolyzed triglyceride-rich lipoproteins such as very low-density lipoproteins (VLDL), and how the resultant lipid droplet formation in monocytes contributes to such activation.

Our studies and others have suggested a link between the consumption of a high-fat meal and monocyte activation (4, 5, 9, 33, 35). A typical Western diet is high in saturated fat, and frequently triggers an increase in circulating triglycerides in normal individuals, primarily packaged as chylomicrons (exogenous pathway) and VLDL (endogenous pathway). These triglyceride (TG)-rich lipoproteins (TGRL) are potentially atherogenic (29, 31, 42), and in vitro studies have shown that monocytes can be activated by TGRL (34). In the circulation, TGRL bind to lipoprotein lipase (LpL) anchored to the surface of endothelial cells. Lipolysis of TGRL by LpL releases free fatty acids, phospholipids, monoglycerides, diglycerides, and remnant particles at the blood-endothelial cell interface. Our studies and others have shown that high physiological concentrations of TGRL lipolysis products activate endothelial cells (8, 32). Further, our studies have shown that VLDL lipolysis products cause the formation of lipid droplets in postprandial human monocytes and THP-1 cells (6).

In this work we tested the hypothesis that TGRL lipolysis products activate and recruit monocytes to endothelium. We propose a novel mechanism of monocyte activation and adhesion induced by VLDL lipolysis products, particularly by free fatty acids. Specifically, VLDL lipolysis products promoted adhesion of freshly isolated human monocytes and THP-1 monocytes to human aortic endothelial cell monolayers by increasing the expression of key alpha/beta integrin heterodimers. Concurrently, VLDL lipolysis products increased peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) and THP-1 monocyte gene expression of proinflammatory cytokines, mediated primarily by Akt and MAP kinases with subsequent nuclear translocation of NFκB and AP-1. Moreover, ERK2 appears to be required for VLDL lipolysis product-induced lipid droplet formation. This study supports the concept that repetitive activation of monocytes by TGRL lipolysis products, as would occur after the repetitive consumption of high-fat meals, increases vascular inflammation and could promote or accelerate atherogenesis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents.

Antibodies to p65, Akt, phospho-Akt, p38, phospho-p38, ERK1/2, phospho-ERK1/2, JNK/SAPK, and phosphor-JNK/SAPK were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology. Inhibitor of kBα (IkBα), phospho-IkBα, cJun, and activated transcription factor-3 (ATF3) antibodies were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Antibodies to p105 and αm-integrin (CD11b) were obtained from Abcam, a beta-actin antibody was obtained from Sigma, and a second CD11b antibody and a secondary anti-rabbit Alexa-488-conjugated antibody were obtained from BD Biosciences. MG-132, LY294002, MEK1/2, Ste-MEK113, SB202190, and SP600125, inhibitors for NFκB, Akt, ERK1/2, ERK2, p38, and JNK, respectively, were obtained from EMD Millipore and used at 25 μM. TNFα protein was obtained from Roche Applied Sciences.

Very low-density lipoprotein isolation.

Male and female healthy human volunteers, ages 12–55, were recruited from the University of California, Davis campus. Informed written consent was given by the donors, or by their parent/guardian if they were minors, and blood was obtained after consumption of a moderately high-fat meal as described previously (16), according to a protocol approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of California, Davis. Plasma was isolated from whole blood and VLDL was isolated using density gradient ultracentrifugation according to standard protocols. For all experiments, lipolysis of VLDL [2.28 mmol/l (200 mg/dl) starting TG] was induced by the addition of bovine lipoprotein lipase (LpL, 2 U/ml, Sigma-Aldrich) for 30 min at 37°C.

Cell culture and isolation.

For experiments using fresh primary monocytes, fasting blood was collected from consented human donors. Isolated buffy coats were used in some experiments, or layered onto Lymphosep medium (MP Biomedicals) for PBMC isolation. Monocytes were further isolated from PBMCs by negative depletion using a Dynabeads Untouched Human Monocyte Isolation kit (Life Technologies). Isolated monocytes were treated at a cell density of 1 × 106 cells/ml for 3 h with gentle agitation at 37°C. Human aortic endothelial cells (HAEC) were obtained from Cascade Biologics and maintained in EGM-2 complete medium (Lonza); 95% confluent monolayers were pretreated with 0.3 nM TNFα for 4 h prior to adhesion experiments. THP-1 monocytes were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) and maintained in suspension between 5 × 104 and 8 × 105 cells/ml in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 2 mM l-glutamine and containing 10 mM HEPES, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 4.5 g/l glucose, 1.5 g/l bicarbonate, 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), and 0.05 mM 2-mercaptoethanol. THP-1 monocyte treatments were conducted at a cell density of 1 × 106 cells/ml for 3 h. Monocytes and endothelial cells were incubated in 5% CO2 and 95% air at 37°C during growth and treatment. For some experiments inhibitors obtained from EMD Chemicals were used at the following concentrations: MG-132 (10 μM), LY294002 (10 μM), MEK1/2 (10 μM), Ste-MEK113 (25 or 50 μM), SB202190 (10 μM), and SP600125 (10 μM). For THP-1 cell imaging, some treated THP-1 cells were allowed to adhere to 0.01% poly-l-lysine-coated coverslips and fixed in 1% paraformaldehyde for 30 min at room temperature. Adherent cells were stained with Oil Red O (Sigma-Aldrich). Briefly, cells were washed with deionized water, incubated in 60% isopropanol for 5 min, and covered in Oil Red O for 5 min at room temperature. Oil Red O stain was removed with 3 deionized water rinses and cells were imaged using an Olympus BX41 bright-field microscope with a 60X, NA 0.80 objective, coupled with an Olympus Qcolor3 digital CCD camera.

Monocyte adhesion assay.

Microfluidic flow channels were used as described previously (37). Briefly, prepared flow chambers were sterilized and vacuum sealed on top of pretreated HAEC monolayers. Treated monocytes were added to an open reservoir on the inlet side of the chamber and “pulled” across the HAEC monolayer by the syringe pump with a constant shear flow rate of 2 dyn/cm2. Digital image sequences of rolling, adherent, and transmigrating monocytes were obtained. Rolling monocytes were identified as those that moved more than one cell diameter in 30 s. Conversely, monocytes were characterized as arrested if they did not move more than one cell diameter in 30 s. Transmigration was defined based on the disappearance of the light reflective capability of monocytes as they transmigrated between endothelial cells. For each experiment, each monocyte treatment was run in duplicate flow chambers, with five 1-min sequences captured per chamber. All adhesive events were counted and reported as average events per minute.

Quantitative real-time PCR for cytokines and integrins.

THP-1 monocytes (1 × 106 cells/ml) were treated as indicated for 3 h. Cells were pelleted and total RNA isolated using TRIzol reagent according to the manufacturer's suggested protocol (Invitrogen). RNA was quantified using a Nanodrop-1000 system (Wilmington, DE), and 2 μg was used to make cDNA with a Superscript II RNase H-reverse transcriptase kit according to the manufacturer's guidelines (Life Technologies). Quantification of mRNA from gene transcripts was performed using the GeneAmp 7900 HT sequence detection system (Life Technologies).

CD11b protein expression by immunofluorescence and flow cytometry.

Treated and washed THP-1 monocytes were adhered to poly-l-lysine-coated coverslips and fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde for 30 min. Cells were then stained with a rabbit monoclonal CD11b antibody (BD Biosciences), followed by a secondary antibody conjugated to Alexa-488. Coverslips were inverted onto glass slides containing a drop of Prolong Gold +DAPI (Life Technologies) and stored overnight in the dark. Images were acquired the next day using an Olympus BX61 microscope with a 40X/1.3 oil immersion objective, coupled with a Pixera Penguin 600 CL cooled camera. Images were acquired using the same exposure time, based on optimal DAPI fluorescence. A minimum of 5 randomly selected images were captured from each of 3 coverslips per treatment from 3 independent experiments. For CD11b measurement by flow cytometry, treated and washed THP-1 monocytes were fixed in 1% paraformaldehyde for 15 min at 37°C. Cells were then washed and blocked with 1% Superblock (Thermo Scientific) in PBS for 30 min and labeled with Alexa488-CD11b for 1 h at 4°C. The percentage of monocytes positive for CD11b surface protein expression was quantified using a Beckman Coulter FC500 flow cytometer. Positive gates were set to 4–5% using unstained monocytes, which was assumed to derive primarily from autofluorescence. The monocyte population was defined by forward (FSC) and side scatter (SSC) characteristics, and a minimum of 10,000 events was counted per treatment in the monocyte gate.

Western blot.

Treated THP-1 monocytes were collected, washed 2 times, and lysed. For some experiments, cytoplasmic and nuclear protein was isolated from monocytes treated with VLDL lipolysis products for 2 h using a NE-PER kit from Pierce. In other experiments, total cellular protein was isolated using a modified RIPA buffer as described previously (20) after 0, 15, 30, 60, or 120 min of treatment. Ten micrograms of protein was separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose. Band intensities were quantified using ImageJ software, and densities were normalized to the total nonphosphorylated protein.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA).

Expression of cytokines such as TNFα and IL-1β and inflammatory mediators such as COX-2 is usually under tight control by NFκB activation and transcription. Concurrently, transcriptional control of IL-8 is tightly regulated by members of the AP-1 superfamily of transcription factors. To determine if both transcription factors are activated by VLDL lipolysis products, nuclear protein was extracted from treated THP-1 monocytes using a nuclear protein isolation kit from Pierce. Three micrograms of nuclear protein was mixed with biotinylated oligonucleotides specific for the active sites of NFκB and AP-1, electrophoresed into a native 6% polyacrylamide gel, and transferred to a nylon membrane according to the manufacturer's instructions (LightShift Chemiluminescent EMSA kit, Pierce). The probe control consisted of only the probe (no nuclear protein), while the cold probe control contained 200-fold molar excess nonbiotinylated probe in addition to the biotinylated probe and nuclear protein to serve as a competition control.

Free fatty acid isolation and characterization.

Postprandial VLDL (2.5 mg TG) was subjected to lipolysis by LpL (2 U/ml) for 30 min at 37°C. The free fatty acid (FFA) fraction was isolated from the total lipolysis products as described previously (40). Briefly, total lipids were extracted using 60 mg Oasis HLB solid-phase extraction cartridges, and the FFA fraction was further separated by elution from aminopropyl solid-phase extraction columns with diethyl ether-acetic acid (98:2 vol/vol). Total FFA were quantified using a clinical kit from Wako Chemicals.

Statistics.

All statistical analyses were performed by one-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons (Tukey) using Prism software. All data are presented as means + standard error of the means (SE). Statistical significance was reported for P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Monocyte adhesive interactions with human aortic endothelial cells are increased by VLDL lipolysis products.

The adhesive capacity of VLDL lipolysis product-treated freshly isolated monocytes to HAECs was examined. HAECs were pretreated with 0.3 ng/ml TNFα to induce the expression of complementary ligands to those expressed on monocytes. Monocytes isolated from fasting human donors were treated with media, LpL, VLDL (2.28 mmol/l TG), or VLDL lipolysis products (2.28 mmol/l TG + 2 U/ml LpL) for 3 h and immediately added to microfluidic flow chambers containing primed HAEC monolayers. The treatment time of 3 h was chosen based on previous in vivo experiments that showed that monocyte TNFα and IL-1β increased maximally 3 h after consumption of a moderately high-fat meal (16). The concentration of VLDL chosen for the lipolysis reaction was 2.28 mmol/l TG, as previous studies have shown that this fits into the lower range of maximal fatty acid release when incubated with LpL (19), where nonesterified fatty acid concentrations roughly paralleled the VLDL triglyceride levels. After ensuring that the monocytes had entered the flow chamber and equilibrated for several minutes, 1-min flow segments were recorded and adherent, rolling, and transmigrating monocytes were counted. Figure 1A shows one frame of a 1-min flow segment taken after 10 s had elapsed, and Fig. 1B shows a frame taken during the same sequence after 45 s had elapsed. These images serve as an example of the adhesive events that were counted, including rolling (r1–r2), arrested (a1–a4), or transmigrating (t1–t3) monocytes. Figure 1C represents the number of monocytes that participated in adhesive events per minute, taken as an average of five separate experiments. Treatment of monocytes with media, LpL, and VLDL resulted in roughly the same number of rolling events per minute (0.8, 1.1, and 1.4, respectively), while VLDL lipolysis product treatment induced 6.2 rolling events per minute. Furthermore, VLDL lipolysis products increased the adhesion of monocytes to endothelial cells (5.0 events per minute) when compared with media, LpL, VLDL, or even monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1) (not shown) (0.5, 0.9, 1.1, and 2.0 events per minute, respectively). Transmigration events were infrequent in these experiments, as the average total flow time for each flow chamber was only 10 min. However, monocytes treated with VLDL lipolysis products transmigrated an average of 0.9 times per minute, compared with 0.3, 0.6, and 0.5 times per minute for media, LpL, and VLDL, respectively. Using a static adhesion assay, we verified that THP-1 monocytes pretreated with VLDL lipolysis products also adhere to HAECs (Fig. 1D).

Fig. 1.

Monocyte adhesive interactions with human aortic endothelial cells are increased by very low-density lipoproteins (VLDL) lipolysis products. Human aortic endothelial cells (HAECs) were treated with TNFα while freshly isolated monocytes (A–C) or THP-1 monocytes (D) were treated with media, lipoprotein lipase (LpL), VLDL, or VLDL + LpL. Monocytes were either injected into a flow chamber for image capture (A and B) and adhesive event quantification (C), or incubated with HAECs under static conditions and adherence quantified (D). A: image of the flow chamber 10 s into the image acquisition sequence with VLDL + LpL-treated monocytes. B: the same frame 45 s after the beginning of image acquisition. Examples of rolling (r1–r2), adherent (a1–a4), and transmigrating (t1–t3) monocytes are labeled. C: counted monocytes that are rolling, adherent, or transmigrating, expressed as the average number of cells per min + SE, from 5 different experiments. D: static adhesion events counted using THP-1 monocytes with indicated treatments. *P < 0.05 from the media control.

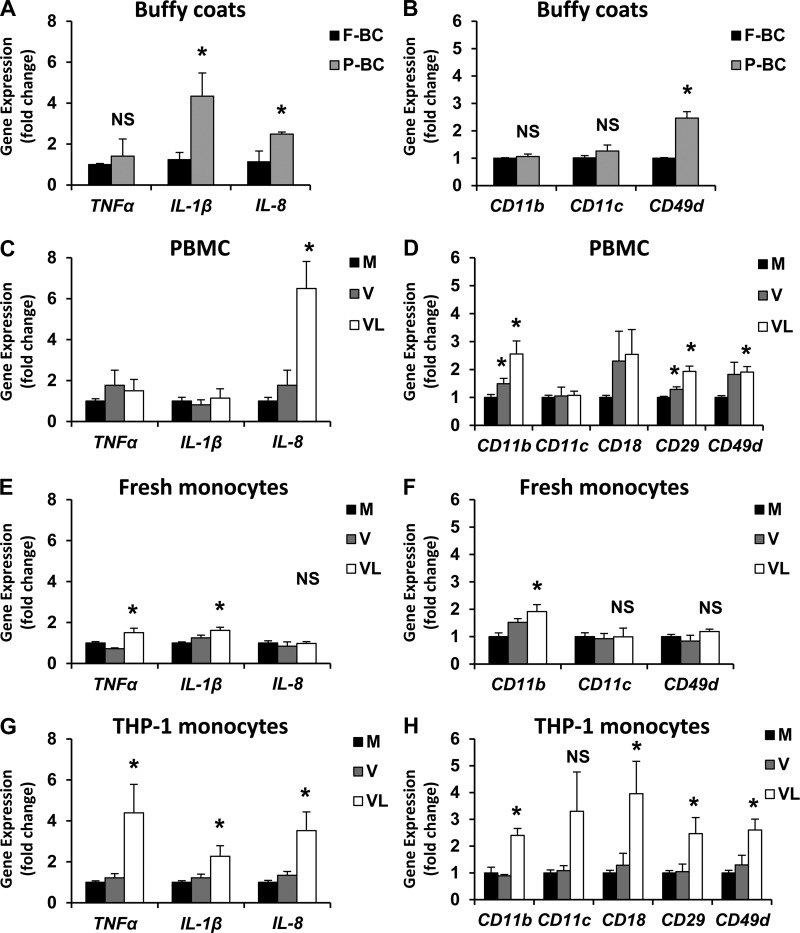

Cytokine and integrin gene and protein expression increase from buffy coats, PBMCs, freshly isolated monocytes, and THP-1 monocytes exposed to VLDL lipolysis products. Postprandial hypertriglyceridemia has been linked to vascular inflammation and atherosclerosis (14). We have shown that elevated blood triglycerides temporally coincide with circulating monocyte activation (16). Moreover, hypertriglyceridemic patients have been reported to have elevated concentrations of soluble adhesion molecules in blood (12), high levels of which are thought to contribute to atherogenesis. Beta-integrins form heterodimers with alpha integrins on the monocyte plasma membrane in the following combinations: Mac-1, or αmβ2 (CD11b, CD18); CR4, or αxβ2 (CD11c, CD18); and VLA-4, or α4β1 (CD49d, CD29). We provide further evidence of postprandial activation of white blood cells in Fig. 2, A and B. Whole buffy coats isolated from fasting donors and again from the same donors after the consumption of a moderately high-fat meal showed increased Il1β, Il8, and Cd49d gene expression in the postprandial state. Using quantitative real-time RT-PCR, mRNA expression of Tnfα, Il1β, Il8, Cd11b, Cd11c, Cd18, Cd29, and Cd49d integrins were measured after treatment with VLDL lipolysis products in PBMCs (Fig. 2, C and D), freshly isolated monocytes (Fig. 2, E and F), and THP-1 monocytes (Fig. 2, G and H). There was a general increase in cytokine and integrin expression by VLDL lipolysis product exposure in these cell populations, most notably from THP-1 monocytes. In addition to gene expression, protein levels of some integrins and cytokines were also measured to confirm translation of mRNA (Fig. 3). Immunofluorescent images and flow cytometry suggest that surface expression of CD11b protein increases with VLDL lipolysis product treatment (Fig. 3, A and B, respectively). It is important to note that the increase in CD11b expression may not be uniformly represented by all cells, as some appear to stain more brightly than others after VLDL + LpL treatment (Fig. 3A). Moreover, secreted TNFα and IL-1β protein also increased in response to VLDL lipolysis products, as measured by ELISA (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 2.

Several monocytic populations show increased gene expression of cytokines and integrins in response to VLDL lipolysis products. A and B: buffy coats were isolated from normal human subjects after an overnight fast (“F”) and after consumption of a moderately high-fat meal (“P”). Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) (C and D), freshly isolated monocytes (E and F), or THP-1 monocytes (G and H) were treated for 3 h with media (M), VLDL (V), or VLDL + LpL (VL) for 3 h. Gene expression levels of inflammatory cytokines (A, C, E, G) and integrins (B, D, F, H) were quantified and normalized to beta-actin and expressed as a fold change from fasting levels (A and B) or media control (C–H) + SE (n = 3–5). *P < 0.05 from the fasting or media control. NS, not significant.

Fig. 3.

Integrin and cytokine protein is also increased by VLDL lipolysis products. Surface CD11b levels were observed from THP-1 monocytes treated with media (M), LpL (L), VLDL (V), or VLDL + LpL (VL) using immunofluorescence and flow cytometry (A and B). A: representative immunofluorescent images of treated THP-1 monocytes stained for CD11b (green) and nuclear DAPI (blue), presented in triplicate (40X). B: relative quantification of CD11b-positive monocytes using flow cytometry (n = 3). Gates were set using unstained cells assuming a background autofluorescence of 4–5%. C: secreted TNFα and IL-1β from treated monocytes was measured by ELISA, and expressed as pg protein/ml + SE (n = 3). *P < 0.05 from the media control.

NFκB and AP-1 nuclear translocation and DNA-binding are increased by VLDL lipolysis products.

To determine if VLDL lipolysis products induced nuclear translocation of NFkB and AP-1 subunits, nuclear protein was isolated for Western blots. VLDL lipolysis products increased levels of the p65 and p50 subunits of NFkB in the nuclear protein fraction. Furthermore, VLDL lipolysis products also increased nuclear levels of cJun and ATF3, subunits of AP-1 (Fig. 4A). The relative density of each band is shown below each lane, normalized to the media control band density.

Fig. 4.

VLDL lipolysis products stimulate NFκB and AP-1 nuclear translocation and activation. THP-1 monocytes were treated with media (M), LpL (L), VLDL (V), or VLDL + LpL (VL) for 2 h, then nuclear protein was isolated. A: 10 μg total nuclear protein was used for Western blots. Band densities relative to the media control (arbitrary units) are shown below each lane (n = 3). B and C: electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSAs) for NFκB and AP-1. Arrows illustrate probe shifts (n = 3).

To determine if DNA binding of NFκB and AP-1 was also increased, EMSAs were performed. DNA binding to NFkB in isolated nuclear protein is shown in Fig. 4B. There was no increased binding activity of NFkB after treatment with media, LpL, or VLDL. Treatment with VLDL lipolysis products resulted in an upward shift in the DNA probe due to slower migration through the gel (arrow), indicating increased DNA binding activity. Lipopolysaccharide (LPS, 0.5 μg/ml) was used as a positive control, and displayed DNA binding activity similar to the lipolysis product treatment. Reactions containing no protein or excess nonbiotinylated probe were used as negative controls, and showed no shift. Similarly, AP-1 DNA binding activity was also evaluated by EMSA (Fig. 4C). Monocyte treatment with VLDL lipolysis products and the LPS positive control increased AP-1 transcriptional activity (arrow). VLDL by itself also increased AP-1 binding activity. There were no shifts observed for the probe-only control, the competition control, the media, or LpL reactions. Therefore, we conclude that NFkB and AP-1 transcriptional activation results from monocyte treatment with VLDL lipolysis products.

MAP kinases, Akt, and IkBα become phosphorylated after VLDL lipolysis product treatment.

To probe the pathways involved in NFκB and AP-1 activation, Western blots were performed to determine the phosphorylation state of several MAP kinases, Akt, and IκBα at various time points after treatment. THP-1 monocytes were treated for 0, 15, 30, 60, or 120 min with LpL, VLDL, or VLDL + LpL, and total intracellular protein was isolated. Monocytes treated with VLDL lipolysis products demonstrated increased phosphorylation of Akt, IκBα, and MAP kinases ERK1/ERK2, p38, and JNK/SAPK (Fig. 5). Specifically, Akt became phosphorylated (Ser 473) after 15 min of VLDL + LpL treatment and remained elevated after 2 h, with a peak band intensity at 30 min. Phosphorylated IκBα (Ser 32) also increased after 15 min of lipolysis product treatment but was not detected at any later time points or in any control treatments. ERK1/2 phosphorylation (Thr 202/Thr 204) of monocytes treated with VLDL + LpL increased by twofold over the LpL and VLDL controls at 30 min and remained elevated throughout the 2 h time point. Similarly, p38 phosphorylation (Thr 180/Tyr 182) after VLDL lipolysis product treatment increased by eightfold over control levels after 30 min, but was reduced to levels just greater than controls by 1 h posttreatment. JNK/SAPK phosphorylation (Thr 183/Tyr 185) increased after 15 min of VLDL lipolysis product treatment and remained elevated through the final 2 h time point. Densitometry analysis, normalized to total nonphosphorylated protein levels, displays the magnitude of phosphorylation achieved for each kinase examined over time. In summary, treatment of monocytes with VLDL lipolysis products results in the rapid phosphorylation of ERK1/2, p38, SAPK/JNK, Akt, and IκBα.

Fig. 5.

Akt, IκBα, ERK1/2, p38, and JNK1/2 become phosphorylated by VLDL lipolysis products. THP-1 monocytes were treated with LpL, VLDL, or VLDL + LpL for 0, 15, 30, 60, or 120 min. A: 10 µg total protein was used for Western blots for each treatment at each time point. B–F: desitometry is represented as mean band intensity of the indicated phosphorylated protein (p-) normalized first to the unmodified protein ± SE, then normalized to the media control (time 0), n = 3. *P < 0.05 from the media control.

NFkB, Akt, and ERK1/2 activation are required for VLDL lipolysis product-induced integrin expression.

To determine which signaling pathways are required for increased monocyte integrin expression in response to VLDL lipolysis products, inhibitors to NFκB, Akt, ERK1/2, p38, and JNK were incubated with THP-1 monocytes prior to treatment with VLDL lipolysis products, and gene expression of integrins was assessed. MG-132 reduces the ubiquitination and subsequent degradation of proteins such as IκBα, allowing it to retain inhibitory control of NFκB. This inhibitor prevents NFκB activation, with negligible effects on AP-1 signaling events. LY 294002 inhibits phosphatidylinositol-3 (PI3) kinase activation, for immediate downstream inhibition of Akt activation with no effects on MAP kinases. The MEK1/2 inhibitor targets both ERK1 and ERK2. SB202190 is a potent inhibitor of p38, without affecting the ERK and JNK pathways. SP600125 specifically inhibits JNK-induced phosphorylation of cJun. As shown in Fig. 6, inhibiting Akt, ERK1/2, and NFkB significantly attenuated expression of all integrins. However, integrin attenuation by p38 and JNK inhibition was minimal, suggesting that AP-1 activation may not be necessary for integrin expression.

Fig. 6.

VLDL lipolysis products increase Akt-, ERK1/2-, and NFkB-mediated expression of CD11b, CD11c, CD18, CD29, and CD49d integrins from THP-1 monocytes. THP-1 monocytes were pretreated with inhibitors to NFκB (MG), Akt (LY), ERK1/2 (MEK), p38 (SB), or JNK (SP) for 1 h, then treated for 3 h with VLDL lipolysis products (VL). Gene expression levels of integrins Cd11b (A), Cd11c (B), Cd29 (C), and Cd49d (D) were normalized to beta-actin and expressed as a percentage of the media control + SEM (n = 5). *P < 0.05 from the media control, #P < 0.05 from the VL treatment. NS, not significant.

Akt and ERK1/2 activation are required for VLDL lipolysis product-induced cytokine expression.

To determine which pathways are involved in the inflammatory response from THP-1 monocytes, inhibitors to NFκB, Akt, ERK1/2, p38, and JNK were incubated with THP-1 monocytes prior to treatment with VLDL lipolysis products, and gene expression of cytokines was assessed. Figure 7 shows that inhibition of Akt and ERK1/2 significantly reduced the expression of all cytokines, while inhibition of NFkB, p38 and JNK had little effect. NFkB inhibition did attenuate Tnfα expression, but had no effect on Il1β or Il8 expression.

Fig. 7.

Akt and ERK1/2 activation are required for VLDL lipolysis product-induced cytokine expression. THP-1 monocytes were pretreated with inhibitors to NFκB (MG), Akt (LY), ERK1/2 (MEK), p38 (SB), or JNK (SP) for 1 h, then treated for 3 h with VLDL lipolysis products (VL). Gene expression levels of cytokines Tnfα (A), Ill1β (B), and Il8 (C) were normalized to beta-actin and expressed as a percentage of the media control + SE (n = 5). *P < 0.05 from the media control, #P < 0.05 from the VL treatment. NS, not significant.

VLDL lipolysis product-induced ERK2 activation is required for lipid droplet accumulation in monocytes.

We have previously reported that monocytes exposed to fatty acids from VLDL lipolysis products accumulate cytosolic lipid droplets (6). To determine if this response to fatty acids is connected with the inflammatory response presented herein, we examined lipid droplet accumulation within THP-1 monocytes that were pretreated with inhibitors to NFκB, Akt, ERK1/2, p38, and JNK, and an inhibitor specific for ERK2 (Ste-MEK113). Treated monocytes were fixed to poly-l-lysine-coated coverslips, and lipid droplets were stained with Oil Red O. Images were captured using light microscopy at 60X magnification. Inhibition of NFκB, Akt, ERK1/2, p38, and JNK did not alter the accumulation of lipid droplets (data not shown). However, when ERK2 specifically was inhibited using Ste-MEK113, lipid droplet accumulation decreased in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 8, E and F). Cell viability was slightly decreased by monocytes treated with VLDL lipolysis products and Ste-MEK113 (not shown), suggesting that ERK2-mediated lipid droplet formation is an essential survival response to fatty acids. More lipid droplets (stained red) accumulate inside monocytes after VLDL + LpL treatment (Fig. 8D) compared with media, Ste-MEK113 alone, or VLDL alone (Fig. 8, A–C).

Fig. 8.

VLDL lipolysis product-induced lipid droplet accumulation within THP-1 monocytes is ERK2-dependent. THP-1 monocytes were treated for 3 h with media, LpL, VLDL (V), VLDL + LpL (VL), or isolated free fatty acids (FFA). For some treatments, THP-1 monocytes were pretreated with an ERK2 inhibitor (Ste-MEK113, 25 or 50 μM as indicated), a neutralizing CD11b antibody, and NFkB inhibitor (MG), or an ERK1/2 inhibitor (MEK) for 1 h. A–F: images of Oil Red O-stained cells were captured using an Olympus BX41 phase-contrast microscope (60X, NA 0.80) with an Olympus Qcolor3 digital CCD camera. Images shown are representative of 3 independent experiments. G–I: relative gene expression analysis was performed to quantify Tnfα, Il1β, and Il8, normalized to beta-actin and presented as a fold change from the media control. J: static adhesion of treated THP-1 monocytes after pretreatment with inhibitors was quantified and presented as adherent cells per frame + SEM (n = 3). K: CD11b surface expression was quantified using flow cytometry and presented as a percentage of cells positive for CD11b (n = 3). *P < 0.05 from the media control, #P < 0.05 from the VL treatment.

Since we have previously shown that lipid droplet accumulation within monocytes is mediated by fatty acids (6), and have also characterized the lipolytically released FFA from postprandial VLDL in our study subjects (40), we determined the effect of free fatty acids released from VLDL lipolysis products on monocyte cytokine and integrin expression. THP-1 monocytes were treated for 3 h with 150 μM FFA extracted from a VLDL + LpL preparation as described by Wang et al. (40), previously shown to consist primarily of palmitic acid (37.8%), stearic acid (7.5%), oleic acid (21.4%), and linoleic acid (15.2%). Treatment with FFA induced greater expression levels of Tnfα, Il1β, Il8, and CD11b than treatment with VLDL lipolysis products (Fig. 8, G–I). Finally, to confirm that changes in inflammatory and integrin gene expression translate into the functional attenuation of monocyte adhesion when certain pathways are inhibited, we performed static adhesion assays. THP-1 monocytes were pretreated with either a neutralizing antibody to CD11b, MG-132 to disrupt NFkB signaling, or the MEK1/2 inhibitor and then treated with VLDL lipolysis products (Fig. 8J). Figure 8K shows that competitive inhibition of CD11b and NFkB attenuate VLDL lipolysis product-induced monocyte adhesion, while ERK1/2 inhibition did not significantly alter adhesion.

DISCUSSION

Postprandial hypertriglyceridemia has been linked to vascular inflammation and atherosclerosis (14). We have shown that elevated blood triglycerides temporally coincide with circulating monocyte activation (16), and that VLDL lipolysis products cause monocytes to form lipid droplets associated with a proinflammatory state (6). In this work we have described a mechanistic association between monocyte activation and exposure to postprandial VLDL lipolysis products. While it is well established that TGRL can activate macrophages (2, 27, 34), no studies have examined the effects of TGRL lipolysis products on naive monocytes. We have shown herein that monocyte expression of cytokines and integrins increases in response to postprandial VLDL lipolysis products. These responses are mediated by Akt and ERK1/2 signaling through NFκB and AP-1, with potential contributions from p38 and JNK1/2, and ERK2 is involved in the accumulation of lipid droplets by FFA released from VLDL with lipolysis. Furthermore, monocyte activation by VLDL lipolysis products translates to increased adhesion to endothelial cells, which is an early event in atherosclerosis development.

Monocyte treatment with VLDL lipolysis products increased monocyte rolling, adhesion, and transmigration between endothelial cells. In support of our findings, Ting et al. (37) reported increased endothelial cell and monocyte interactions when HAECs had been pretreated with TGRL. Such treatment enhanced endothelial cell inflammatory signaling through Akt, ERK, and p38 with cotreatment with TNFα. Furthermore, Saxena et al. (32) showed increased monocyte adherence to VLDL lipolysis product-treated porcine aortic endothelial cells and suggested that fatty acids released from lipolysis enhanced adhesion. Our study reveals for the first time that monocytes treated with VLDL lipolysis products adhere to endothelium with a much higher frequency than untreated monocytes or monocytes treated with a prototypic monocyte agonist, MCP-1 (not shown).

We have shown that PBMC and THP-1 monocyte treatment with VLDL lipolysis products increased the expression of Tnfα, Il1β, and Il8 significantly more than treatment with VLDL alone. Notably, VLDL by itself had no effect on monocyte cytokine expression, which is in disagreement with previous studies by Stollenwerk et al. (34). However, monocyte-derived macrophages and longer treatment times were utilized in their experiments, which could explain the divergent findings. Our study showed that inhibiting the activation of NFκB attenuated Tnfα expression in response to VLDL lipolysis products but not Il1β or Il8 expression. Previous evidence suggests that AP-1 can induce IL-1b expression independently of NFkB, but NFkB is essential for TNFα expression (38). Furthermore, IL-8 expression has been shown to be under the control of signaling mediators upstream from AP-1 response elements, such as Akt and ERK1/2, further supported by our results. It is also possible that early response cytokines, such as TNF and IL-1, could then stimulate IL-8 expression, as shown by Thornton et al. (36).

Firm adhesion of monocytes to endothelial cells is mediated by the activation of β1 and β2 integrins (15). β2-Integrins are not constitutively avid for their endothelial receptors but must become activated by chemotactic agents. β2-Integrins such as CD18 are uniformly expressed in a low-affinity state and upon stimulation are rapidly redistributed into clusters for efficient tethering during shear flow (24). VLDL lipolysis product treatment of PBMCs and THP-1 monocytes resulted in increased expression of Cd11b, Cd11c, Cd18, Cd29, and Cd49d integrins, as measured by quantitative real-time PCR. Expression of integrins has been shown to be regulated by the NFκB pathway (1), which also was activated by VLDL lipolysis products. Recently, it has been shown that ERK1/2, NFκB, and Akt are all involved in β1-integrin expression from human breast cancer cells (41). Our results are in agreement, as we have shown that pharmacological inhibition of NFκB and ERK1/2 attenuated VLDL lipolysis product-induced expression of Cd11b, Cd11c, Cd29, and Cd49d.

In addition to increased cytokine and integrin expression, VLDL lipolysis product-treated monocytes showed increased NFkB and AP-1 nuclear translocation and transcriptional activity. NFκB activation is a hallmark of the classic inflammatory signaling cascade that has been reported following VLDL treatment (7, 37), and often works synergistically with AP-1 (13). In addition, AP-1 activation typically leads the cell down a survival/proliferation pathway, which is a previously reported effect of VLDL treatment (7). The apparent constitutive ATF3 activation seen herein has been reported previously in macrophages (18) and has recently been reported as a key response element to TGRL lipolysis products in arterial endothelial cells (3), which combined with the AP-1 activation by both VLDL and VLDL lipolysis products suggests that VLDL induces a stress response. This confirms previous results from Stollenwerk et al. (34), that VLDL activates AP-1 through ERK1/2 activation.

The FFAs generated during the lipolysis reaction could be responsible for the observed proinflammatory effect. Our VLDL lipolysis products recently have been characterized, and palmitic acid is the most abundantly released nonesterified fatty acid by bovine LpL (40). Long-chain saturated fatty acids, such as palmitic acid, have been shown to induce TNFα, IL-1β, and IL-8 secretion and mRNA expression from macrophages by activation of NFκB through Akt and AP-1 through p38 and JNK (17, 21, 23). Therefore, the proinflammatory effects seen after treatment with the FFA fraction most likely reflect saturated fatty acid treatment, although recent data suggest that other fatty acid classes may be involved (25, 33). Furthermore, it is now well established that endogenous saturated fatty acids contribute to TLR4 activation (22), and VLDL treatment increases TLR4 expression from endothelial cells (26). The TLR4-induced signaling pathway has been well characterized to include activation of MAP kinases, Akt, and NFκB.

We have previously reported that fatty acids induce lipid droplet formation within monocytes, and that this process is linked to a proinflammatory cellular status (6). In this work we have shown that lipid droplet formation is dependent on ERK2 activation. ERK2 inhibition dramatically attenuated lipid droplet accumulation after VLDL lipolysis product treatment at the expense of cell viability, which suggests that lipid droplet formation is essential for survival against lipotoxicity. Recently Gower et al. (9) have confirmed the positive correlation between circulating postprandial triglycerides and lipid droplet-laden monocytes, and further reported that these monocytes expressed higher levels of CD11c. Our work lends support to this notion that postprandial triglycerides and fatty acids can activate monocytes by specific proinflammatory pathways.

In summary, we have shown for the first time that monocytes exposed to lipolysis products from postprandial VLDL demonstrate increased cytokine and integrin expression, characteristic of monocyte inflammation and activation. The expression of proinflammatory cytokines and integrins induced by lipolysis products was the result of NFκB and AP-1 activation by both Akt- and ERK2-dependent pathways. Furthermore, VLDL lipolysis products increased monocyte rolling, arrest, and diapedesis between endothelial cells, indicating that the proinflammatory effects of VLDL lipolysis products contribute to a functional, and potentially pathogenic, end point. Finally, the ERK2-dependent accumulation of lipid droplets in monocytes suggests that the cytokine and integrin responses could represent a survival pathway against lipotoxicity. This work indicates that the repetitive spike in triglyceride-rich lipoproteins with increased release of lipolysis products seen in some individuals following the consumption of a moderately high-fat meal could trigger inflammatory events such as monocyte activation, with the potential for enhanced vascular inflammation and accelerated atherosclerosis development.

GRANTS

This work was supported by the Nora Eccles Treadwell Foundation, the Training Program in Biomolecular Technology (T32-GM08799) at the Univ. of California Davis, the National Science Foundation's Center for Biophotonics Science and Technology (CBST) at the Univ. of California Davis, and National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grant RO1-HL-055667.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: L.J.d.H. conception and design of research; L.J.d.H., R.A., and J.E.N. performed experiments; L.J.d.H. and J.E.N. analyzed data; L.J.d.H. and J.C.R. interpreted results of experiments; L.J.d.H. prepared figures; L.J.d.H. drafted manuscript; L.J.d.H., R.A., and J.C.R. edited and revised manuscript; L.J.d.H., R.A., J.E.N., and J.C.R. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge Yen Trang Vo and Danielle Baute for help in recruiting human subjects for VLDL isolation, and Limin Wang for assistance in free fatty acid isolation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ali S, Mann DA. Signal transduction via the NF-kappaB pathway: a targeted treatment modality for infection, inflammation and repair. Cell Biochem Funct 22: 67–79, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alipour A, van Oostrom AJ, Izraeljan A, Verseyden C, Collins JM, Frayn KN, Plokker TW, Elte JW, Castro Cabezas M. Leukocyte activation by triglyceride-rich lipoproteins. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 28: 792–797, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aung HH, Lame MW, Gohil K, An CI, Wilson DW, Rutledge JC. Induction of ATF3 gene network by triglyceride-rich lipoprotein lipolysis products increases vascular apoptosis and inflammation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 33: 2088–2096, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bermudez B, Lopez S, Varela LM, Ortega A, Pacheco YM, Moreda W, Moreno-Luna R, Abia R, Muriana FJ. Triglyceride-rich lipoprotein regulates APOB48 receptor gene expression in human THP-1 monocytes and macrophages. J Nutr 142: 227–232, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bouwens M, Grootte Bromhaar M, Jansen J, Müller M, Afman LA. Postprandial dietary lipid-specific effects on human peripheral blood mononuclear cell gene expression profiles. Am J Clin Nutr 91: 208–217, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.den Hartigh LJ, Connolly-Rohrbach JE, Fore S, Huser TR, Rutledge JC. Fatty acids from very low-density lipoprotein lipolysis products induce lipid droplet accumulation in human monocytes. J Immunol 184: 3927–3936, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dichtl W, Nilsson L, Goncalves I, Ares MP, Banfi C, Calara F, Hamsten A, Eriksson P, Nilsson J. Very low-density lipoprotein activates nuclear factor-kappaB in endothelial cells. Circ Res 84: 1085–1094, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eiselein L, Wilson DW, Lamé MW, Rutledge JC. Lipolysis products from triglyceride-rich lipoproteins increase endothelial permeability, perturb zonula occludens-1 and F-actin, and induce apoptosis. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 292: H2745–H2753, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gower RM, Wu H, Foster GA, Devaraj S, Jialal I, Ballantyne CM, Knowlton AA, Simon SI. CD11c/CD18 expression is upregulated on blood monocytes during hypertriglyceridemia and enhances adhesion to vascular cell adhesion molecule-1. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 31: 160–166, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Greaves DR, Channon KM. Inflammation and immune responses in atherosclerosis. Trends Immunol 23: 535–541, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guijas C, Pérez-Chacón G, Astudillo AM, Rubio JM, Gil-de-Gómez L, Balboa MA, Balsinde J. Simultaneous activation of p38 and JNK by arachidonic acid stimulates the cytosolic phospholipase A2-dependent synthesis of lipid droplets in human monocytes. J Lipid Res 53: 2343–2354, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hackman A, Abe Y, Insull W, Pownall H, Smith L, Dunn K, Gotto AM, Ballantyne CM. Levels of soluble cell adhesion molecules in patients with dyslipidemia. Circulation 93: 1334–1338, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hess J, Angel P, Schorpp-Kistner M. AP-1 subunits: quarrel and harmony among siblings. J Cell Sci 117: 5965–5973, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Higgins LJ, Rutledge JC. Inflammation associated with the postprandial lipolysis of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins by lipoprotein lipase. Curr Atheroscler Rep 11: 199–205, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hynes RO. Integrins: versatility, modulation, and signaling in cell adhesion. Cell 69: 11–25, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hyson DA, Paglieroni TG, Wun T, Rutledge JC. Postprandial lipemia is associated with platelet and monocyte activation and increased monocyte cytokine expression in normolipemic men. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost 8: 147–155, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Håversen L, Danielsson KN, Fogelstrand L, Wiklund O. Induction of proinflammatory cytokines by long-chain saturated fatty acids in human macrophages. Atherosclerosis 202: 382–393, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khuu CH, Barrozo RM, Hai T, Weinstein SL. Activating transcription factor 3 (ATF3) represses the expression of CCL4 in murine macrophages. Mol Immunol 44: 1598–1605, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krauss RM, Levy RI, Fredrickson DS. Selective measurement of two lipase activities in postheparin plasma from normal subjects and patients with hyperlipoproteinemia. J Clin Invest 54: 1107–1124, 1974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lagoumintzis G, Xaplanteri P, Dimitracopoulos G, Paliogianni F. TNF-alpha induction by Pseudomonas aeruginosa lipopolysaccharide or slime-glycolipoprotein in human monocytes is regulated at the level of Mitogen-activated Protein Kinase activity: a distinct role of Toll-like receptor 2 and 4. Scand J Immunol 67: 193–203, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Laine PS, Schwartz EA, Wang Y, Zhang WY, Karnik SK, Musi N, Reaven PD. Palmitic acid induces IP-10 expression in human macrophages via NF-kappaB activation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 358: 150–155, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee JY, Sohn KH, Rhee SH, Hwang D. Saturated fatty acids, but not unsaturated fatty acids, induce the expression of cyclooxygenase-2 mediated through Toll-like receptor 4. J Biol Chem 276: 16683–16689, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee JY, Ye J, Gao Z, Youn HS, Lee WH, Zhao L, Sizemore N, Hwang DH. Reciprocal modulation of Toll-like receptor-4 signaling pathways involving MyD88 and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/AKT by saturated and polyunsaturated fatty acids. J Biol Chem 278: 37041–37051, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lum AF, Green CE, Lee GR, Staunton DE, Simon SI. Dynamic regulation of LFA-1 activation and neutrophil arrest on intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1) in shear flow. J Biol Chem 277: 20660–20670, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Matesanz N, Jewhurst V, Trimble ER, McGinty A, Owens D, Tomkin GH, Powell LA. Linoleic acid increases monocyte chemotaxis and adhesion to human aortic endothelial cells through protein kinase C- and cyclooxygenase-2-dependent mechanisms. J Nutr Biochem 23: 685–690, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Norata GD, Pirillo A, Callegari E, Hamsten A, Catapano AL, Eriksson P. Gene expression and intracellular pathways involved in endothelial dysfunction induced by VLDL and oxidised VLDL. Cardiovasc Res 59: 169–180, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Noti JD. Expression of the myeloid-specific leukocyte integrin gene CD11d during macrophage foam cell differentiation and exposure to lipoproteins. Int J Mol Med 10: 721–727, 2002 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Osterud B, Bjorklid E. Role of monocytes in atherogenesis. Physiol Rev 83: 1069–1112, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rapp JH, Lespine A, Hamilton RL, Colyvas N, Chaumeton AH, Tweedie-Hardman J, Kotite L, Kunitake ST, Havel RJ, Kane JP. Triglyceride-rich lipoproteins isolated by selected-affinity anti-apolipoprotein B immunosorption from human atherosclerotic plaque. Arterioscler Thromb 14: 1767–1774, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ross R. Atherosclerosis is an inflammatory disease. Am Heart J 138: S419–420, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rutledge JC, Ng KF, Aung HH, Wilson DW. Role of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins in diabetic nephropathy. Nat Rev Nephrol 6: 361–370, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Saxena U, Kulkarni NM, Ferguson E, Newton RS. Lipoprotein lipase-mediated lipolysis of very low density lipoproteins increases monocyte adhesion to aortic endothelial cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 189: 1653–1658, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schirmer SH, Werner CM, Binder SB, Faas ME, Custodis F, Böhm M, Laufs U. Effects of omega-3 fatty acids on postprandial triglycerides and monocyte activation. Atherosclerosis 225: 166–172, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stollenwerk MM, Lindholm MW, Pörn-Ares MI, Larsson A, Nilsson J, Ares MP. Very low-density lipoprotein induces interleukin-1beta expression in macrophages. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 335: 603–608, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Strohacker K, Breslin WL, Carpenter KC, Davidson TR, Agha NH, McFarlin BK. Moderate-intensity, premeal cycling blunts postprandial increases in monocyte cell surface CD18 and CD11a and endothelial microparticles following a high-fat meal in young adults. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab 37: 530–539, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thornton AJ, Ham J, Kunkel SL. Kupffer cell-derived cytokines induce the synthesis of a leukocyte chemotactic peptide, interleukin-8, in human hepatoma and primary hepatocyte cultures. Hepatology 14: 1112–1122, 1991 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ting HJ, Stice JP, Schaff UY, Hui DY, Rutledge JC, Knowlton AA, Passerini AG, Simon SI. Triglyceride-rich lipoproteins prime aortic endothelium for an enhanced inflammatory response to tumor necrosis factor-alpha. Circ Res 100: 381–390, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Trede NS, Tsytsykova AV, Chatila T, Goldfeld AE, Geha RS. Transcriptional activation of the human TNF-alpha promoter by superantigen in human monocytic cells: role of NF-kappa B. J Immunol 155: 902–908, 1995 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.van Oostrom AJ, Rabelink TJ, Verseyden C, Sijmonsma TP, Plokker HW, De Jaegere PP, Cabezas MC. Activation of leukocytes by postprandial lipemia in healthy volunteers. Atherosclerosis 177: 175–182, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang L, Gill R, Pedersen TL, Higgins LJ, Newman JW, Rutledge JC. Triglyceride-rich lipoprotein lipolysis releases neutral and oxidized FFAs that induce endothelial cell inflammation. J Lipid Res 50: 204–213, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wei YY, Chen YJ, Hsiao YC, Huang YC, Lai TH, Tang CH. Osteoblasts-derived TGF-beta1 enhance motility and integrin upregulation through Akt, ERK, and NF-kappaB-dependent pathway in human breast cancer cells. Mol Carcinog 47: 526–537, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zilversmit DB. A proposal linking atherogenesis to the interaction of endothelial lipoprotein lipase with triglyceride-rich lipoproteins. Circ Res 33: 633–638, 1973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]