Abstract

Background:

To examine the efficacy of sequential sertraline and cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) treatment relative to CBT with pill placebo over 18 weeks in children and adolescents with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD).

Methods:

Forty-seven children and adolescents with OCD (Range=7-17 years) were randomized to 18-weeks of treatment in one of three arms: 1) sertraline at standard dosing + CBT (RegSert+CBT); 2) sertraline titrated slowly but achieving at least 8 weeks on the maximally tolerated daily dose + CBT (SloSert+CBT); or 3) pill placebo + CBT (PBO+CBT). Assessments were conducted at screening, baseline, weeks 1-9, 13, and 17, and post- treatment. Raters and clinicians were blinded to sertraline (but not CBT) randomization status. Primary outcomes included the Children’s Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale, and response and remission status. Secondary outcomes included the Child Obsessive Compulsive Impact Scale–Parent/Child, Children’s Depression Rating Scale-Revised, Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children, and Clinical-Global Impressions-Severity.

Results:

All groups exhibited large within-group effects across outcomes. There was no group by time interaction across all outcomes suggesting that group changes over time were comparable.

Conclusions:

Among youth with OCD, there was no evidence that sequentially provided sertraline with CBT differed from those receiving placebo with CBT.

Keywords: Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder, Children, Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy, Treatment, Sertraline

Pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) affects ~1% of children and adolescents and is associated with marked functional impairment (Piacentini, Bergman, Keller, & McCracken, 2003) and a high probability of secondary diagnoses (Geller et al., 2003). Most affected individuals experience symptom onset during childhood with symptoms running a protracted course in the absence of appropriate intervention (Pauls, Alsobrook, Goodman, Rasmussen, & Leckman, 1995). Two treatments have demonstrated efficacy: cognitive- behavioral therapy (CBT) and serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SRI) medications. Current practice parameters recommend that clinicians begin with CBT alone for mild to moderate OCD presentations and use combined CBT-SRI treatment in moderate to severe presentations (AACAP, 2012). Yet, studies directly examining the efficacy of combining CBT and SRI medications have yielded unequivocal results. Among pediatric OCD samples, only one study has prospectively examined the efficacy of combined therapy relative to CBT alone finding that combined treatment was superior to CBT and sertraline alone (Cohen's d=1.40 vs. 0.97 and 0.67; (POTS, 2004). However, a site effect was present with CBT alone associated with a robust effect at one site (d=1.60) and a modest effect at the other (d=0.51), while sertraline yielded effects of moderate and large sizes at different sites (d=0.53 and 0.80).

More information on the relative benefits of combined CBT and SRI therapy versus CBT alone has been reported in adults with OCD. Several studies have found positive results in support of combined treatment. Marks and colleagues (Marks et al., 1988; Marks, Stern, Mawson, Cobb, & McDonald, 1980) found an additive effect of combined clomipramine and CBT relative to placebo and CBT. Hohagen et al. (Hohagen et al., 1998) compared CBT+fluvoxamine to CBT+placebo in 58 adults. More patients were classified as responders to CBT+fluvoxamine treatment versus CBT+placebo. Others have not found additional benefit with combined treatment. van Balkom et al. (van Balkom et al., 1998) randomized 117 adult patients to one of five conditions: 1) cognitive therapy for 16 weeks; 2) CBT for 16 weeks; 3) fluvoxamine for 16 weeks plus cognitive therapy for weeks 9-16; 4) fluvoxamine for 16 weeks plus CBT for weeks 9-16; or 5) eight-week wait-list control. Active treatments did not differ and there was no benefit to the sequential combination of fluvoxamine with either therapy versus other conditions. Foa et al. (Foa et al., 2005) examined the comparative efficacy of intensive CBT for four weeks followed by eight weekly maintenance sessions, clomipramine alone, their combination, or placebo for 12 weeks in 122 adults with OCD. All treatments were efficacious, with a distinct advantage for CBT alone or in combination with clomipramine, which did not differ. Cottraux et al. (Cottraux et al., 1990) randomized 60 patients to one of three conditions lasting 24 weeks each: weekly CBT+fluvoxamine, weekly CBT+placebo, and fluvoxamine. No significant group differences were present at post-treatment.

Implications of the extant combination trials are that CBT and SRIs are effective acute treatments for pediatric and adult OCD when administered alone and in conjunction. It remains unclear, however, if a combined approach has incremental benefits over CBT monotherapy. This holds relevance because although safe, pharmacological interventions involving serotonergic medications may be accompanied by side effects (Murphy, Segarra, Storch, & Goodman, 2008) and may not be an acceptable intervention to some parents. On balance, the majority of the studies reviewed above conducted combined treatment simultaneously. An adequate trial of an SRI is 10-12 weeks with some data suggesting that optimal response cannot be determined until after 18-20 weeks of treatment (Walsh & McDougle, 2004). Thus, trials that combine treatments simultaneously may not provide the best test of combined pharmacological and psychosocial approaches. Intuitively, the effects of combined treatment would be optimized using sequential rather than simultaneous study designs, with an adequate medication trial initiated first. Use of this methodology prior to initiating CBT may facilitate exposure to feared situations vis-à-vis reductions in baseline levels of anxiety or treatment complicating factors (e.g., depression). Yet, the majority of studies have initiated psychosocial and pharmacological treatment regimens simultaneously usually for 12 weeks, preventing the optimal dose from being reached by the end of the trial. Further, since dissemination of CBT for OCD is fairly limited, the sequential addition of CBT to patients who have been treated with SRI medications may parallel the real world and provide insight into treatment options for those who do not respond to initial efforts.

To date, several sequential trials in adults with OCD and one in children with OCD have been conducted. Franklin et al. (Franklin et al., 2011) (2011) randomized 124 youth with OCD who remained symptomatic following an adequate SRI trial to CBT+continued SRI, a brief version of CBT+continued SRI, or continued SRI therapy alone. The CBT+SRI arm was superior to the other groups on all outcomes. As noted, van Balkom et al. (van Balkom et al., 1998) indicated no benefit to the sequential combination of fluvoxamine with either therapy versus other conditions. Tenneij et al. (Tenneij, van Megen, Denys, & Westenberg, 2005) examined the addition of CBT to venlafaxine (300mg/day) or paroxetine (60mg/day) responders (N=96). Medication responders were randomly assigned to either receive the addition of CBT (18 45-minute sessions) or continue drug treatment for an additional six-months. Those who received CBT augmentation showed a greater improvement in symptoms and remission rates than those who continued on medication treatment alone.

In the present study, we had a unique opportunity to examine the efficacy of sequential sertraline and CBT treatment relative to CBT alone. The study design involved children and adolescents with OCD being randomized to 18-weeks of sertraline or placebo with CBT being initiated four weeks after pharmacotherapy onset: 1) sertraline at standard dosing + CBT (RegSert+CBT); 2) sertraline titrated slowly but achieving at least 8 weeks on the maximally tolerated daily dose + CBT (SloSert+CBT); or 3) pill placebo + CBT (PBO+CBT). We were interested in determining if symptom reduction and response/remission rates differed as a function of both group and medication status (i.e., sertraline arms collapsed versus PBO+CBT). Secondary analyses examined group differences in child-reported anxiety and depressive symptoms and parent- and child-rated impairment.

Method

Participants

Forty-seven youth ages 7-17 years with a principal diagnosis of OCD were recruited between February 2009 and January 2011 across two study sites with expertise in pediatric OCD treatment.Ω Inclusion criteria consisted of: 1) Current DSM-IV-TR diagnosis of OCD established via expert clinician assessment and the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children (KSADS-PL; (Kaufman et al., 1997); 2) Children’s Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (CY-BOCS) ≥ 18 (Scahill et al., 1997); 3) English speaking and able to read. Exclusion criteria included: 1) Prior adequate trial of (AACAP, 2012) or allergy to sertraline. 2) History of rheumatic fever, serious autoimmune disorder, or generally poor physical health. 3) Inability to swallow study medication. 4) Presence of active suicidality or suicide attempt in the past 12 months. 5) Pregnancy or having unprotected sex [in females]. 6) Concomitant psychotropic medications other than medication for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder or PRN sedative/hypnotics for insomnia. 7) Presence of comorbid psychosis, bipolar disorder, autism, anorexia, or substance abuse/dependence.

Procedures

Appropriate institutional review board permissions from both sites were obtained. After obtaining written parent consent and child assent, participants completed study measures, were administered a physical examination by a board certified child psychiatrist, and had lab values assayed (e.g., CBC, metabolic panel, urine toxicology, and pregnancy test [for post-pubescent females]). Thereafter, eligible participants were randomized by a computer-generated randomization program in a double-blinded fashion (for sertraline/placebo but not CBT) to one of the three study arms: 1) RegSert+CBT; 2) SloSert+CBT; or 3) PBO+CBT. Assessments were conducted by trained raters at screening, baseline, weeks 1-9, 13, and 17, and post-treatment, with the post-treatment assessment within one-week of the final treatment visit. Independent evaluators were clinicians trained by the first, second, and last author in the administration of clinician-rated measures through instructional meetings, in vivo observation, and direct supervision.

Pharmacotherapy

Patients were randomly assigned to receive sertraline regular or slow dose titration or placebo in a 1:1:1 fashion for 18 weeks. The titration schedule for those randomized to the RegSert arm used a flexible upward titration from 25 mg/day to 200 mg/day over 9 weeks unless higher doses were not tolerated, after which the dosage was adjusted as a function of tolerability. If tolerated, maximum dose could be achieved in 5 weeks. The titration schedule for those in the SloSert arm utilized a slower titration schedule relative to the RegSert arm. Unless unable to tolerate higher doses, children remained on 25mg/day for the first two weeks, 50mg/day from weeks 3-4, 75mg/day for weeks 5-6, 100mg/day for week 7, 150mg/day for week 8, and 200mg/day for week 9 until the end of the study. Thus, subjects in SloSert did not reach the therapeutic dose defined as a balance of efficacy and tolerability of up to 150mg/day until week 8 relative to week 4 for RegSert. However, those assigned to SloSert still had at least 10 weeks on maximally tolerated daily dose when they reached the final study visit. Across all study arms, dosage increases were delayed or dosages reduced for clinically significant adverse effects, e.g., those producing distress and dysfunction for which the clinician and the patient or parent believed dosage reduction was indicated. Medication was administered in one daily dose, typically following breakfast. Pharmacotherapy was provided by an experienced board certified child and adolescent psychiatrist at each site over 18 weekly sessions. These sessions lasted 30 minutes each, were supportive in nature, and excluded any active CBT elements (e.g., exposure and response prevention [E/RP], cognitive therapy). Medication compliance was monitored at each visit through a medication diary and pill counts.

Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy

Starting after four weeks of sertraline/placebo, all participants received 14 weekly CBT sessions lasting approximately 60 minutes each. Treatment was based on the protocol used in POTS (POTS, 2004) which includes psychoeducation, cognitive training, and E/RP. Sessions 1-4 were devoted to psychoeducation, cognitive therapy, hierarchy development, and an initial ‘easy’ exposure; sessions 5-14, focused on E/RP exercises in a graduated manner. Treatment plans were individually tailored to address patient-specific symptoms, as well as other needs (e.g., family accommodation, developmental level). Between session homework was assigned (~60 minutes daily) consisting of exposures to stimuli similar to those addressed in session. Parts of the final two sessions were used for relapse prevention planning. Therapy was provided by experienced clinical psychology postdoctoral fellows with expertise in CBT for pediatric OCD who were supervised by the 1st or 4th authors between each session. Treatment integrity was ensured through the use of session content checklists that corresponded to the treatment manual, weekly supervision, and evaluation of 10% of randomly selected videotaped therapy sessions by the first author.

Measures

K-SADS-PL

The K-SADS-PL (Kaufman et al., 1997) is a clinician-administered, semi-structured diagnostic interview for DSM-IV childhood disorders which was administered to parents and children separately to determine primary and comorbid diagnoses.

Children’s Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (CY-BOCS)

The CY-BOCS is a psychometrically sound (Scahill et al., 1997; Storch et al., 2004) clinician-rated, semi-structured interview assessing the severity of obsessive-compulsive symptoms. The CY-BOCS rates the severity of obsessions and compulsions across five items each (time occupied by symptoms, interference, distress, resistance, and degree of control over symptoms) and provides a total severity score.

Clinical Global Impression-Severity (CGI-Severity)

The CGI-Severity (National Institute of Mental, 1985) is a 7-point clinician rating of severity of psychopathology (0=no illness, 6=extremely severe) that demonstrates treatment sensitivity (Storch, Lewin, De Nadai, & Murphy, 2010).

Children’s Depression Rating Scale-Revised (CDRS-R)

The CDRS-R (Poznanski & Mokros, 1996) is a semi-structured interview with the child and caregiver that assesses the presence and severity of depressive symptoms across 17 symptom areas.

Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children (MASC)

The MASC (March, Parker, Sullivan, Stallings, & Conners, 1997) is a psychometrically-sound self-report questionnaire that assesses anxiety symptoms.

Child Obsessive Compulsive Impact Scale-Child and Parent Versions (COIS-C/P)

The COIS-C/P (Piacentini et al., 2003) are 56-item self- or parent-report measures which assess OCD-related impairment in school, social, and home/family domains.

Analytic Plan

The primary outcomes included the CY-BOCS total score, and response (defined by a 30% CY-BOCS reduction) and remission rates (defined by CY-BOCS total scores below 10). Prior to examining outcomes, we evaluated whether the groups were comparable in terms of their demographic characteristics to evaluate whether randomization was successful. As well, there were no site effects on baseline clinical or sociodemographic characteristics, nor any site effects for study outcomes. Thus, analyses are presented for the total sample. To examine changes in outcomes as a function of intervention group, random effects models using SAS Proc Mixed were used (Littell, Milliken, Stroup, Wolfinger, & Schabenberger, 2006). This method provides the same basic information as does a repeated measures analysis of variance, but is more flexible in terms of allowing for unbalanced research designs, as well as for the inclusion of all persons in the analysis, not just those who contributed complete longitudinal information (Singer & Willett, 2003). Specifically, for persons who were missing information from an assessment timepoint, a maximum likelihood estimate based estimate was used for the missing information, which is less conservative than using the last observation carried forward (Hamer & Simpson, 2009). In these analyses, the key term is the group X time interaction, which evaluates the extent to which the groups exhibit comparable changes over the treatment period. Although the study sample size was modest, the density of observations results in a statistical power of .80 to detect a group X time interaction of f=0.57 for the three group comparison with the sample size of 47, which would be deemed a clinically meaningful group difference. Stated differently, effect sizes of a smaller magnitude would not be of interest given the increased complexity and side effect risk associated with multimodal intervention.

Results

Demographic Characteristics

The final doses for the RegSert+CBT and SloSert+CBT were 164.3mg/day and 95.6mg/day, respectively. Sample demographic characteristics are shown in Table 1. There were no baseline group differences in age (F(2, 44)=.54, p=.59), gender (×2(2)=1.21, p=.55), and CY-BOCS scores (F(2, 44)=1.51, p=.23).

Table 1.

Demographic and baseline clinical characteristics of the sample

| RegSert+CBT (n=14) |

SloSert+CBT (n=17) |

PBO+CBT (n=16) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender N (% Female) | 50.0 | 35.3 | 31.2 |

| Age, M (SD) | 11.57 (3.06) | 11.47 (3.68) | 12.63 (3.63) |

| CY-BOCS Total | 23.64 (4.48) | 26.65 (5.68) | 25.06 (4.01) |

| CY-BOCS Obsessions | 11.43 (3.03) | 12.88 (2.55) | 12.31 (2.24) |

| CY-BOCS Compulsions | 12.21 (2.36) | 13.76 (3.46) | 12.75 (1.95) |

| Psychiatric comorbidity, N (%) | |||

| Internalizing | 7 (50%) | 7 (41.2%) | 10 (62.5%) |

| Externalizing | 3 (21.4%) | 1(5.9%) | 6 (37.5%) |

| Tic Disorder | 3 (21.4%) | 2 (11.8%) | 6 (37.5%) |

Note. CY-BOCS=Children’s Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale

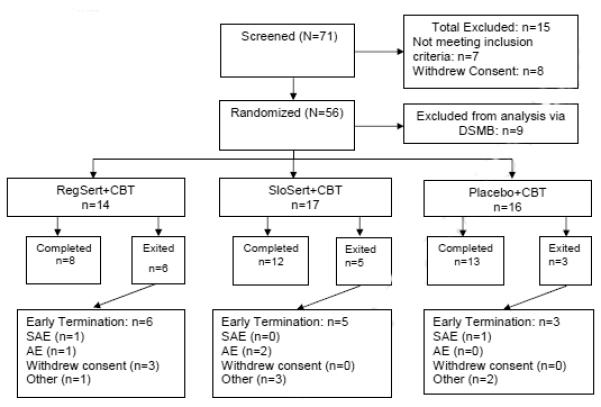

Overall, attrition was 29.8% (14/47), which was related, in part, due to early termination of 4 subjects related to a packaging error by the investigational pharmacy, which resulted in a study suspension for active participants.Ω In the RegSert+CBT arm, 6/14 (42.9%) youth dropped out before completing all study procedures (1 before CBT started, 1 each following CBT sessions 1 and 2, 2 after CBT session 13, and 1 after session 4 due to study suspension). In the SloSert+CBT arm, 5/17 (29.4%) youth dropped out before completing all study procedures (2 before CBT started, 1 after CBT session 1, and 2 after sessions 3 and 9 due to study suspension). In the PBO+CBT arm, 3/16 (18.8%) youth dropped out before completing all study procedures (1 each after CBT sessions 1 and 8, and 1 after session 6 due to study suspension). Thus, 6/14 subjects withdrew from the study prior to receiving their 2nd CBT session while another 4/14 subjects withdrew due to the study suspension. See Figure 1 for the study flow-chart.

Figure 1.

Study Flow Chart.

Longitudinal Changes by Treatment Group

Continuous Outcomes

Table 2 provides baseline and post-treatment descriptive statistics as a function of group status. Table 3 displays results of the random effects models describing changes over time. As a guide to this table, the “intercept” reflects the value of the outcome at the point of study randomization to groups, “time” represents change per assessment over the treatment period, “group” indicates whether there were group differences at the randomization point, and “group × time” indicates whether the groups changed at differential rates over treatment. Several comparisons for treatment group are shown in Table 3. The first row represents the three-level treatment group variable. The following rows pair one group and compare changes with the other two. Beginning with the three-level group, outcomes declined significantly over treatment. Within-group effect sizes were large for the RegSert+CBT, SloSert+CBT, and PBO+CBT arms (d=1.01, 1.42, and 1.80), and when considering those who received sertraline versus placebo (d=1.25 and 1.80). However, in each case the group × time interaction was not statistically significant suggesting the changes over time were comparable across groups.

Table 2.

Means and Standard Deviations for Outcome Measures at Baseline and Post-Assessments

| Measure | Timepoint | Regular Sertraline + CBT M (SD) |

Slow Sertraline + CBT M (SD) |

Placebo + CBT M (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CY-BOCS Total | Baseline Post- treatment |

23.64 (4.48) 15.43 (9.72) |

26.65 (5.68) 17.18 (7.60) |

25.06 (4.01) 15.56 (6.62) |

| CY-BOCS Obsessions | Baseline Post- treatment |

11.43 (3.03) 7.00 (4.59) |

12.88 (2.55) 8.35 (4.05) |

12.31 (2.24) 7.81 (3.31) |

| CY-BOCS Compulsions |

Baseline Post- treatment |

12.21 (2.36) 8.43 (5.32) |

13.76 (3.46) 8.82 (3.72) |

12.75 (1.95) 7.75 (3.80) |

| CGI-Severity | Baseline Post- treatment |

4.36 (.49) 3.36 (1.34) |

4.82 (.64) 3.65 (1.12) |

4.63 (.72) 3.37 (0.89) |

| MASC | Baseline Post- treatment |

51.93 (22.05) 31.50 (22.71) |

45.35 (19.11) 33.33 (23.09) |

45.87 (19.47) 28.00 (18.30) |

| COIS-C | Baseline Post- treatment |

14.31 (11.62) 6.17 (8.57) |

17.20 (12.97) 8.47 (14.09) |

16.27 (13.03) 9.60 (9.44) |

| COIS-P | Baseline Post- treatment |

19.92 (13.27) 17.27 (15.79) |

24.60 (18.86) 14.64 (15.34) |

17.40 (15.17) 12.67 (14.23) |

| CDRS-R | Baseline Post- treatment |

33.43 (8.76) 25.83 (8.73) |

33.06 (10.10) 24.93 (8.09) |

33.19 (11.60) 27.93 (11.07) |

Note. CY-BOCS=Children’s Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale; CGI-Severity=Clinical Global Impressions-Severity; MASC=Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children; COIS-C/P=Children’s Obsessive-Compulsive Impact Scale-Child/Parent Versions; CDRS-R=Children’s Depression Rating Scale-Revised

Table 3.

Results of Random Effects Models as a Function of Outcome and Group Membership

| Parameter Est. (SE) |

CY-BOCS Total |

CY-BOCS Obsessions |

CY-BOCS Compulsions |

CGI- Severity |

MASC Total |

COIS-C Total |

COIS-P Total |

CDRS-R Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Three-level group | ||||||||

| Intercept | 23.92 (1.07)*** | 11.57 (.56)*** | 12.33 (.57)*** | 4.61 (.16)*** | 49.29 (4.67)*** | 16.05 (2.74)*** | 24.30 (3.27)*** | 29.72 (2.11)*** |

| Time | −.09 (.02)*** | −.05 (.01)*** | −.05 (.01)*** | −.01 (.00)*** | −.16 (.02)*** | −.13 (.04)** | −.16 (.04)*** | −.04 (.02)* |

| Group | 1.59 (.82) | .81 (.43) | .77 (.44) | .09 (.12) | .00 (.56) | 2.27 (2.08) | −.95 (2.48) | 1.43 (1.61) |

| Group X Time | .00 (.01) | .00 (.00) | .00 (.00) | .00 (.00) | .00 (.02) | .00 (.03) | .01 (.02) | −.01 (.01) |

| RegSert+CBT vs. | ||||||||

| others | ||||||||

| Intercept | 22.93 (1.15)*** | 11.03 (.60)*** | 11.92 (.62)*** | 4.47 (.18)*** | 50.80 (5.21)*** | 15.34 (3.04)*** | 24.06 (3.64)*** | 29.55 (2.35)*** |

| Time | −.08 (.02)*** | −.04 (.01)*** | −.04 (.01)*** | −.01 (.00)*** | −.20 (.03)*** | −.13 (.05)* | −.15 (.04)** | −.04 (.02) |

| Group | 3.74 (1.37)** | 1.95 (.72)** | 1.74 (.74)* | .33 (.21) | −2.16 (6.22) | 4.39 (3.63) | −1.10 (4.35) | 2.36 (2.81) |

| Group X Time | −.01 (.02) | .00 (.01) | .00 (.01) | .00 (.00) | .06 (.03) | .01 (.06) | −.01 (.05) | −.01 (.03) |

| SloSert+CBT vs. | ||||||||

| others | ||||||||

| Intercept | 27.09 (1.09)*** | 13.23 (.57)*** | 13.79 (.58)*** | 4.93 (.16)*** | 46.87 (4.68)*** | 19.51 (2.80)*** | 23.74 (3.34)*** | 31.42 (2.16)*** |

| Time | −.10 (.02)*** | −.05 (.01)*** | −.05 (.01)*** | −.01 (.00)*** | −.12 (.05)* | −.13 (.04)** | −.18 (.03)*** | −.05 (.02)** |

| Group | −2.39 (1.36) | −1.31 (.71) | −1.02 (.73) | −.36 (.20) | 4.27 (5.85) | −1.71 (3.50) | −.65 (4.15) | −.33 (2.69) |

| Group X Time | .02 (.02) | .01 (.01) | .01 (.01) | .00 (.00) | −.10 (.06) | .00 (.05) | .04 (.04) | .00 (.03) |

| PBO+CBT vs. | ||||||||

| others | ||||||||

| Intercept | 26.26 (1.15)*** | 12.73 (.60)*** | 13.52 (.61)*** | 4.66 (.17)*** | 50.63 (4.87)*** | 19.97 (2.87)*** | 22.26 (3.38)*** | 32.43 (2.21)*** |

| Time | −.08 (.02)*** | −.04 (.01)*** | −.05 (.01)*** | −.01 (.00)*** | −.19 (.02)*** | −.12 (.04)** | −.14 (.04)*** | −.06 (.02)** |

| Group | −1.03 (1.42) | −.48 (.74) | −.58 (.75) | .06 (.21) | −2.02 (5.99) | −2.35 (3.54) | 1.63 (4.18) | −1.85 (2.72) |

| Group X Time | −.01 (.02)a | −.01 (.01) | .00 (.01) | .00 (.00) | .05 (.03) | −.01 (.05) | −.03 (.04) | .01 (.02) |

Note. CY-BOCS=Children’s Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale; CGI-Severity=Clinical Global Impressions-Severity; MASC=Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children; COIS-C/P=Children’s Obsessive-Compulsive Impact Scale-Child/Parent Versions; CDRS-R=Children’s Depression Rating Scale-Revised.

Cohen’s d for the comparison of subjects who received sertraline versus placebo equaled d=.11

The results for the pairwise comparisons largely mirrored the results with the three-level treatment group factor. That is, when one group was compared to the two others, results were comparable to when all three groups were compared to one another. Effect sizes between the RegSert+CBT group versus the SloSert+CBT and the PBO+CBT arms were small (d=0.20 and 0.02), as was the effect between SloSert+CBT and PBO+CBT (d=0.23). Overall, results indicated significant improvement across primary and secondary outcomes, but that changes were comparable across groups.

Categorical Outcomes

Overall, 61.7% (29/47) of youth were treatment responders. There were no group differences in rates of treatment response (57.1% for RegSert+CBT; 64.7% for SloSert+CBT; 62.5% for PBO+CBT; X2=0.19, p=.91). Only 27.7% (13/47) of the overall sample had a CY-BOCS total score <10 following treatment. Although remission was more common in the RegSert+CBT group, this did not statistically differ from other groups (42.9% for RegSert+CBT; 23.5% for SloSert+CBT; 18.8% for PBO+CBT; X2=2.39, p=.30).

Safety and Tolerability

Regular monitoring of adverse events was conducted by an independent data and safety monitoring board (DSMB). The consort chart (Figure 1) shows screening, randomization and study completion status for study arms. There were two serious adverse events (AEs), one in the RegSert+CBT and Placebo+CBT groups each. The former consisted of a hospitalization for behavioral exacerbation initially thought to be possibly related to study medication, but it was subsequently disclosed that the subject had exhibited similar behavior prior to the study and in final analysis the AE was not deemed related. The latter consisted of a hospitalization due to pneumonia that was deemed unrelated to study medication. Both serious AEs resulted in termination prior to CBT initiation. Table 4 reports adverse events occurring in at least 5% of patients. There were no statistically significant differences using Fisher’s Exact Test for any of the AEs, but consistent with the expected side effect profile of SSRIs, youth exposed to sertraline had over twice the rate of decreased appetite and diarrhea compared to those exposed to placebo, and over twice the rate of exacerbated behavior problems. However, there were no differences in recorded AEs for emergent suicidal ideation between those receiving sertraline versus placebo.

Table 4.

Adverse Events in Youth Treated with Sertraline+CBT relative to Placebo+CBT

| Adverse Event | Sertraline+CBT N=31 N(%) |

Placebo+CBT N=16 N(%) |

|---|---|---|

| Decreased Appetite | 9(29) | 1(6) |

| Diarrhea | 10(32) | 2(13) |

| Common Cold | 4(13) | 2(13) |

| Exacerbated Behavior Problem | 6(19) | 1(6) |

| Fatigue | 4(13) | 2(13) |

| Fever | 5(16) | 1(6) |

| Headache | 16(52) | 8(50) |

| Insomnia | 11(35) | 3(19) |

| Irritability | 3(10) | 4(25) |

| Jittery | 5(16) | 0(0) |

| Muscle Pain | 6(19) | 2(13) |

| Nausea | 3(10) | 2(13) |

| Skin Picking | 5(16) | 0(0) |

| Sore Throat | 7(23) | 3(19) |

| Stomachache | 6(19) | 5(31) |

| Suicidal Ideation | 2(6) | 3(19) |

| Tics | 3(10) | 2(13) |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 5(16) | 5(31) |

| Vomiting | 3(10) | 2(13) |

Discussion

Prior clinical trials in pediatric and adult OCD have frequently utilized designs that relied on the simultaneous combination of pharmacological and psychosocial treatments that may not provide an optimal test of medication benefits given the latency until optimal effects may be achieved. The present study examined sequential sertraline and CBT treatment relative to pill placebo and CBT alone in reducing obsessive-compulsive symptoms among youth with OCD. Currently, it remains unclear as to whether combined treatment yields improved outcomes relative to CBT monotherapy. The POTS trial (POTS, 2004),on average, found that combined treatment was superior to CBT and sertraline alone in children with moderately severe OCD. However, when broken down by site, the effect size at one site for CBT alone was comparable to the effect size for combined treatment (d=1.60 and 1.40). In the present study, there was consistently no evidence that the sequential combination of sertraline with CBT in pediatric OCD was more effective than CBT alone. Lack of group differences may be reflective of the strong efficacy of exposure-based CBT that allows for little further improvement, measurement issues with primary outcomes (i.e., nonlinearity of the CY-BOCS in which lower scores are rare; (Foa et al., 2005) and use of a sample with moderate to severe symptoms. Clinically, sequential sertraline may prove most beneficial when anxiety or other problems (e.g., depression) are preventing CBT engagement, when symptoms are markedly severe and/or in the presence of past failed CBT monotherapy. In other words, in a group not specifically selected for extreme symptom severity, multimodal therapy may not provide an additional advantage over CBT monotherapy. Although the use of a placebo arm allowed us to conclusively test whether combined treatment is superior to CBT monotherapy, placebo is not an inactive intervention, as it harnesses treatment expectancy and included, like in the sertraline arms, frequent interactions with experienced treating physicians.

When benchmarking findings of the present investigation relative to others, study findings are comparable. Within group effect sizes found for the CBT arm were robust and comparable to others (Franklin et al., 2011; POTS, 2004). Although similar to POTS (POTS, 2004), the relatively low remission rates may be attributable to several factors including the difficulty of achieving clinical remission in pediatric OCD, the relatively high drop-out rates early in treatment and due to study suspension, and/or that the primary aim of the larger project was to examine behavioral side effects in relation to sertraline treatment. Stated differently, study dosing strategies may have differed from applied clinical practice in which upward titration of medication would be used in the instance of partial response after an adequate sertraline trial.

Although not statistically significant, it is important to note that remission rates in the RegSert+CBT arm were approximately twice that of other conditions, perhaps suggesting increased likelihood of achieving remission with more aggressive multimodal treatment versus monotherapy. Psychosocial treatment studies for pediatric OCD have often yielded somewhat higher remission rates than those involving multimodal treatment. We speculate that those families willing to participate in a multimodal intervention may have a child with additional clinical complexities that may result in slightly attenuated – but still impressive – response and remission rates.

Analysis of secondary outcomes showed reductions in non-OCD anxiety, depressive symptoms, and OCD-related impairment across groups, which did not differ. These data suggest the value of CBT alone or with sertraline in reducing other functional outcomes. While identifying reductions in obsessive-compulsive symptom severity is a central focus in studies like the present, addressing co-occurring problems that the child may experience is critical for improving quality of life and functioning.

Several study limitations merit consideration. First, although multiple assessment timepoints enhanced statistical power, the sample size was modest. With that said, sample size was unlikely the source of the non-significant interactions between group and time. The group differences at the last time point for the major outcomes were all below a standardized mean difference of .25 and would require hundreds of participants in order to render these differences statistically significant. Moreover, the sample size precludes evaluation of treatment mediators and moderators. Indeed, baseline obsessive-compulsive severity might moderate outcome such that combined treatment yielded incremental effects among the more severe patients. Second, study attrition (14/47) was relatively high, especially in the RegSert+CBT arm. Partially this was due to a pharmacy-related medication error that resulted in the premature termination of 4 subjects due to a temporary study suspension. Six subjects dropped out prior to their 2nd CBT session and two dropped out at session 13. Thus, the attrition rate observed is a reflection of multiple factors versus a reflection of CBT difficulty. Third, the sample was primarily Caucasian, which limits generalizability. Fourth, beyond within-site supervision and regular between-site conference calls, no formal assessment of rater integrity was conducted. Finally, no follow-up beyond the post-treatment evaluation was conducted.

In sum, our data suggest that CBT monotherapy yields comparable effects to combined treatment in youth with moderately severe OCD symptoms. Importantly, these data highlight the importance of disseminating CBT to community mental health providers outside of specialized university centers. Currently, SRI medications, either alone or with psychotherapy (often not CBT), are frequently used as the initial intervention in youth with OCD despite more modest efficacy (but greater dissemination) relative to CBT and the potential for side effects. Although improving, relatively few mental health professionals are adequately trained in exposure-based CBT (Marques et al., 2010). In its absence, clinicians and families encounter a dilemma regarding the relative benefits (i.e., efficacy, relative ease of implementation) and risks (i.e., safety, partial response) of SRI use, especially in less severe cases. The use of innovative approaches to improve treatment access (e.g., telemedicine, stepped-care approaches) and outcome (e.g., d-cycloserine) may represent possible solutions to this service-delivery gap. In addition, attention to outcome moderators is needed to individualize treatment approaches to patient characteristics. Existing studies, including the present, have yet to answer the questions of which patient characteristics necessitate more aggressive treatment strategies. This domain is highlighted as critical to advancing the literature beyond first-generation outcome studies that give us estimates of average patient response.

Supplementary Material

Highlights

It is unclear if combined antidepressant and cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) is superior to CBT alone for pediatric OCD.

• This study examined the efficacy of sequential sertraline and CBT relative to CBT with pill placebo in pediatric OCD.

• Multimodal therapy did not show an advantage over CBT monotherapy in youth with OCD.

• Multimodal treatment may be most beneficial when clinical features inhibit CBT engagement or OCD symptoms are severe.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Author Note

This work was supported by grants to the first (L40-MH081950-02), second and last authors from the National Institutes of Health (R01MH078594-01). Pfizer provided sertraline and matching placebo at no cost. The authors would like to acknowledge the contributions of Drs. Ayesha Lall (Private practice), P. Jane Mutch (University of South Florida), Amaya Ramos (Private practice), and Mark Yang (deceased), and Ms. Dana Mason (University of Florida).

Footnote

Ω During the conduct of the study, a pharmacy-related medication error occurred, which affected 9 of 56 initially randomized study participants and resulted in a temporary study suspension. After full root-cause analysis was completed and the study was reopened, the DSMB advised to conduct analyses including the 47 unaffected subjects (the treatment of 4 of these subjects was terminated early due to the study suspension).

References

- AACAP Practice Parameters for the Assessment and Treatment of Pediatric Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- Cottraux J, Mollard E, Bouvard M, Marks I, Sluys M, Nury AM, et al. A controlled study of fluvoxamine and exposure in obsessive-compulsive disorder. International Clinical Psychopharmacology, 1990;5(1):17–30. doi: 10.1097/00004850-199001000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Liebowitz MR, Kozak MJ, Davies S, Campeas R, Franklin ME, et al. Randomized, placebo-controlled trial of exposure and ritual prevention, clomipramine, and their combination in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. American Journal Psychiatry. 2005;162:151–161. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.1.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin ME, Sapyta J, Freeman JB, Khanna M, Compton S, Almirall D, et al. Cognitive behavior therapy augmentation of pharmacotherapy in pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder: the Pediatric OCD Treatment Study II (POTS II) randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2011;306(11):1224–1232. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geller DA, Biederman J, Stewart SE, Mullin B, Farrell C, Wagner KD, et al. Impact of comorbidity on treatment response to paroxetine in pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder: is the use of exclusion criteria empirically supported in randomized clinical trials? Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology. 2003;13(1):S19–S29. doi: 10.1089/104454603322126313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamer RM, Simpson PM. Last observation carried forward versus mixed models in the analysis of psychiatric clinical trials. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2009;166:639–641. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09040458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hohagen F, Winkelmann G, Rasche-Ruchle H, Hand I, Konig A, Munchau N, et al. Combination of behaviour therapy with fluvoxamine in comparison with behaviour therapy and placebo. Results of a multicentre study. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1998;(35):71–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, Rao U, Flynn C, Moreci P, et al. Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children-Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL): initial reliability and validity data. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36(7):980–988. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199707000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littell RC, Milliken GA, Stroup WW, Wolfinger RD, Schabenberger O. SAS for Mixed Models. 2nd SAS Press; Cary, NC: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- March JS, Parker JD, Sullivan K, Stallings P, Conners CK. The Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children (MASC): factor structure, reliability, and validity. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36(4):554–565. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199704000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks IM, Lelliott P, Basoglu M, Noshirvani H, Monteiro W, Cohen D, et al. Clomipramine, self-exposure and therapist-aided exposure for obsessive-compulsive rituals. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1988;152:522–534. doi: 10.1192/bjp.152.4.522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks IM, Stern RS, Mawson D, Cobb J, McDonald R. Clomipramine and exposure for obsessive-compulsive rituals: i. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1980;136:1–25. doi: 10.1192/bjp.136.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marques L, LeBlanc NJ, Weingarden HM, Timpano KR, Jenike M, Wilhelm S. Barriers to treatment and service utilization in an internet sample of individuals with obsessive-compulsive symptoms. Depression and Anxiety. 2010;27:470–475. doi: 10.1002/da.20694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy TK, Segarra A, Storch EA, Goodman WK. SSRI adverse events: how to monitor and manage. International Review of Psychiatry. 2008;20(2):203–208. doi: 10.1080/09540260801889211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Mental, H. CGI (Clinical Global Impression) Scale -- NIMH. Psychopharmacology Bulletin. 1985;21:839–844. [Google Scholar]

- Pauls DL, Alsobrook JP, Goodman W, Rasmussen S, Leckman JF. A family study of obsessive-compulsive disorder. American Journal Psychiatry. 1995;152:76–84. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.1.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piacentini J, Bergman RL, Keller M, McCracken J. Functional impairment in children and adolescents with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology. 2003;13(1):S61–S69. doi: 10.1089/104454603322126359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- POTS Cognitive-behavior therapy, sertraline, and their combination for children and adolescents with obsessive-compulsive disorder: the Pediatric OCD Treatment Study (POTS) randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;292(16):1969–1976. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.16.1969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poznanski EO, Mokros HB. Children's Depression Rating Scale-Revised. Western Psychological Services; Los Angeles: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Scahill L, Riddle MA, McSwiggin-Hardin M, Ort SI, King RA, Goodman WK, et al. Children's Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale: reliability and validity. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36(6):844–852. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199706000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer JD, Willett JB. Applied longitudinal data analysis: Modeling change and event occurrence. Oxford University Press; New York, NY: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Storch EA, Lewin AB, De Nadai AS, Murphy TK. Defining treatment response and remission in obsessive-compulsive disorder: a signal detection analysis of the Children's Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2010;49(7):708–717. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storch EA, Murphy TK, Geffken GR, Soto O, Sajid M, Allen P, et al. Psychometric evaluation of the Children's Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale. Psychiatry Research. 2004;129(1):91–98. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2004.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tenneij NH, van Megen HJ, Denys DA, Westenberg HG. Behavior therapy augments response of patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder responding to drug treatment. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2005;66(9):1169–1175. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n0913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Balkom AJ, de Haan E, van Oppen P, Spinhoven P, Hoogduin KA, van Dyck R. Cognitive and behavioral therapies alone versus in combination with fluvoxamine in the treatment of obsessive compulsive disorder. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1998;186(8):492–499. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199808000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh KH, McDougle CJ. Pharmacological augmentation strategies for treatment- resistant obsessive-compulsive disorder. Expert Opinions in Pharmacotherapy. 2004;5(10):2059–2067. doi: 10.1517/14656566.5.10.2059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.