Abstract

Objective

Building on prior efficacy trials (i.e., university based, graduate students as therapists), the primary purpose of this study was to determine whether favorable 12-month outcomes obtained in a randomized effectiveness trial (i.e., implemented by practitioners in a community mental health center) of multisystemic therapy (MST) with juveniles who had sexually offended (JSO) were sustained through a second year of follow-up.

Method

JSO (n = 124 male youth) and their families were randomly assigned to MST, which was family based and delivered by community-based practitioners, or to treatment as usual (TAU), which was primarily group-based cognitive-behavioral interventions delivered by professionals within the juvenile justice system. Youth averaged 14.7 (SD = 1.7) years of age at referral, were primarily African American (54%), and 30% were Hispanic. All youth had been diverted or adjudicated for a sexual offense. Analyses examined whether MST effects reported previously at 1-year follow-up for problem sexual behaviors, delinquency, substance use, and out-of-home placement were sustained through a second year of follow-up. In addition, arrest records were examined from baseline through 2-year follow-up.

Results

During the second year of follow-up, MST treatment effects were sustained for three of four measures of youth problem sexual behavior, self-reported delinquency, and out-of-home placements. The base rate for sexual offense rearrests was too low to conduct statistical analyses, and a between-groups difference did not emerge for other criminal arrests.

Conclusions

For the most part, the 2-year follow-up findings from this effectiveness study are consistent with favorable MST long-term results with JSO in efficacy research. In contrast with many MST trials, however, decreases in rearrests were not observed.

Keywords: Juvenile sex offender, randomized controlled trial, treatment, follow-up

This 2-year follow-up examined the sustainability of 1-year treatment effects that were observed in an effectiveness trial of multisystemic therapy (MST; Henggeler, Schoenwald, Borduin, Rowland, & Cunningham, 2009) with juveniles who sexually offend (JSO). The effectiveness trial (Letourneau et al., 2009) demonstrated favorable MST treatment effects at 1-year post-referral for sexual behavior problems, delinquency, and costly out-of-home placements. These findings were consistent with two prior efficacy studies of MST, which reported strong long-term reductions in JSO recidivism and incarceration rates (Borduin, Henggeler, Blaske, & Stein, 1990; Borduin, Schaeffer, & Heiblum, 2009)

Such findings have important implications for practice and policy. The results suggest that JSO, who account for a substantial proportion of sexual harm, particularly against younger children (Finkelhor, Ormrod, & Chaffin, 2009), can be treated effectively in the community with family-based services. Moreover, the findings indicate the potential of significant cost savings, as about 26% of treatment services for JSO are provided in costly residential or secure settings (McGrath, Cumming, Burhard, Zeoli, & Ellerby, 2010).

In further consideration of these practice and policy implications, the primary purpose of this study was to evaluate whether MST treatment effects reported by Letourneau and colleagues at 1-year post-referral were sustained during a second year of follow-up. In addition, this study also examined rearrest rates from time of referral through the 2-year follow-up. We hypothesized that, relative to youth who received treatment as usual for JSO (i.e., primarily cognitive-behavioral group treatment), youth in the MST condition would sustain their treatment gains through the second year of follow-up and evidence significantly fewer rearrests.

Method

Design and Procedures

Study design and procedures are described more fully in earlier publications (Henggeler et al., 2009; Letourneau et al., 2009). Briefly, a 2 (treatment type: MST vs. treatment as usual [TAU]) × 5 (time: baseline, 6, 12, 18, and 24 months post baseline) factorial design with random assignment of youth to treatment conditions was used. Blocked randomization was used to guard against unequal distribution of participants with child versus peer victims. The present report focuses on the second year of follow-up (i.e., 18 and 24 months post baseline). Arrest outcomes were calculated from baseline through the 2-year follow-up. Research assessments collected at the five time points included demographic information, youth and caregiver reports on youth sexual risk behaviors, and youth reports on delinquency and substance use. During brief monthly telephone assessments, all caregivers reported on youth placements and caregivers of youth in active MST treatment also completed an MST therapist adherence questionnaire. Caregivers were compensated with $30 for up to five assessments and $10 for up to 10 brief phone interviews. Three university institutional review boards approved study procedures and a federal confidentiality certificate provided additional protection for participants. Data collection was not blind to condition except for the baseline assessment, which preceded randomization.

Participants

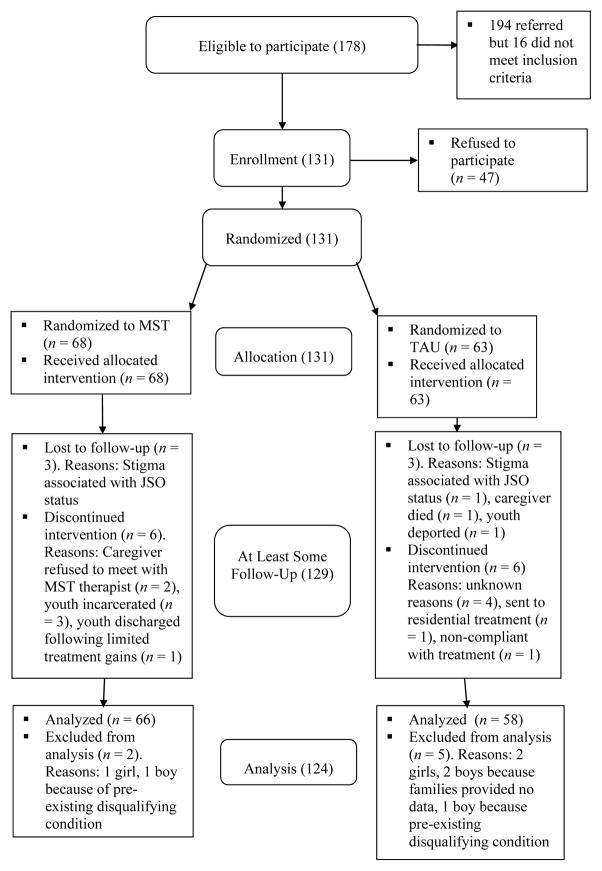

Figure 1 depicts the flow of participants from referral through the end of follow-up. All participants were referred from the district State’s Attorney after having been charged with a sexual offense (i.e., the index offense). To be eligible for this study, youth must have been (a) ordered to outpatient sex offender treatment following either diversion (i.e., where the prosecutor has discretion to drop charges if youth complies with specific requirements) or adjudication (i.e., where the youth has been formally adjudicated delinquent of an offense) for the index offense, (b) residing with a caregiver and not in temporary care, (c) 11 to 17 years of age, and (d) absent of current psychotic symptoms or serious developmental delay. Participants had to be fluent in English or Spanish. To improve generalizability of results, youth were not excluded on the basis of other mental health or behavioral problems. Of 178 eligible youth, 131 were recruited (i.e., 74% recruitment rate, see Figure 1) and 124 contributed data to the current study. Of the seven youth not contributing data to the present study, two withdrew without providing any study data, two were removed after pre-existing disqualifying conditions were identified, and three were girls whose data were removed to improve generalizability of findings to the broader literature, which tends to focus on sex offenses committed by boys. Assessment completion rates at baseline and 18 and 24 months post baseline were 100%, 93%, and 92%, respectively.

Figure 1.

Sampling and flow of participants.

Youth were 14.7 (SD = 1.7) years of age at recruitment. Most youth were African-American (54%) or White (44%); and 30% indicated Hispanic ethnicity. The most common index offense charges included aggravated criminal sexual assault (32%), criminal sexual assault (15%), aggravated criminal sexual abuse (15%), and criminal sexual abuse (24%). More than one-third (38%) of the sample had prior nonsexual offenses. See Letourneau et al. (2009) for additional offense and caregiver characteristics.

Intervention Conditions

Across conditions, adjudicated youth (n = 69 or 56%) were required to attend outpatient sex offender treatment and subjected to other probation conditions (e.g., meetings with probation officers, community service). Diverted youth (n = 55 or 44%) were required to attend outpatient sex offender treatment but had few other requirements.

MST

MST is a family- and community-based treatment for adolescents presenting serious behavioral and clinical problems and at imminent risk of out-of-home placement. MST is well-specified (Henggeler et al., 2009) and well-supported, with 10 published randomized trials with delinquent youth and their families (Henggeler, Sheidow, & Lee, 2007). MST clinicians develop and direct interventions toward ameliorating individual, family, peer, school, and community factors that are linked directly and/or indirectly with the youth’s presenting problems; with caregivers viewed as the keys to achieving sustainable outcomes. Therapists draw upon evidence-based intervention strategies such as pragmatic family therapy approaches and cognitive behavioral therapy interventions to address relevant factors. The central emphasis of MST is usually to develop parenting competencies and to overcome any barriers (e.g., caregiver skill deficits, substance abuse, lack of social support) to achieving those competencies.

Standard MST intervention and quality assurance procedures (e.g., Henggeler, Schoenwald et al., 2009) were followed in this study. Four therapists with caseloads of 4–6 families and an on-site MST supervisor comprised the MST team. Therapists delivered interventions primarily in families’ homes and elsewhere as needed (e.g., schools), and families had 24-hour/7 day-a-week access to their therapist or another team member. Individualized assessments were conducted with youth, family members, and other important members of youths’ social ecologies (e.g., probation officers) to develop treatment goals and identify the factors considered most relevant to initiation and/or maintenance of the problem sexual behavior. Individualized treatment plans were developed and well-validated treatment strategies were employed to address the factors associated with sexually abusive and other antisocial behaviors. Caregiver participation was a critical component of all treatment plans and improved parenting was shown to mediate favorable outcomes with these youth (Henggeler, Letourneau et al., 2009).

The standard MST intervention was enhanced to account for clinical issues more common or pertinent to JSO and their families. As specified in a supplemental therapist training manual (Borduin, Letourneau, Henggeler, Saldana, & Swenson, 2005), additional protocols addressed youth and caregiver denial about the offense, safety planning to minimize risk of reoffending, and promotion of age-appropriate and normative peer social relationships. With respect to denial, therapists were trained to determine whether caregiver denial interfered with treatment goals and, if so, to identify and address reasons for the denial (e.g., fear of additional social consequences). With respect to safety, therapists were trained to conduct a functional analysis of the index offense and target the behavioral drivers and other factors leading up to the offense for change. For example, if easy access to younger children was a driver of the youth’s offending behavior, the therapist would work with caregivers to eliminate such access or ensure adequate supervision. With respect to age-appropriate and normative social experiences with peers, therapists were trained to include strategies for identifying prosocial peers among a youth’s acquaintances and to assist parents to facilitate prosocial interactions (e.g., by providing pizza for a home movie night). Therapists also worked with caregivers and youth to identify and access desirable after-school and community activities.

As reported previously (Letourneau et al., 2009), fidelity to the MST model did not achieve levels reported for previous studies and families remained in treatment for an average of 7 months (SD = 3 months), which is longer than typical for MST targeting general delinquency but not for MST targeting JSO (Borduin et al., 1990; Borduin et al., 2009).

Treatment as usual

The TAU condition was implemented primarily by the juvenile sexual offender unit of the juvenile probation department. Here, cognitive-behavioral therapy with relapse prevention was delivered to groups of 8 to 10 youth during weekly 60-minute treatment sessions. Treatment targeted deviant sexual interests, victim empathy, cognitive distortions, and relapse prevention. Youth with co-morbid problems (e.g., substance abuse) were referred to external agencies for treatment and treatment could be augmented with family or individual youth sessions. No instrument was available to assess therapist fidelity to the TAU intervention; however, caregiver-reported client satisfaction ratings were high, as previously reported, supporting the viability of this model. In addition, five families made arrangements for private treatment, and data from these youth were retained in the statistical analyses. Youth remained in TAU for an average of 12.48 months (SD = 9.92 months).

Therapist Characteristics

Therapist characteristics are described in detail elsewhere (Letourneau et al., 2009). Briefly, MST was provided by five clinicians (three with master’s degrees, one who completed his doctorate during the project and one with a bachelor’s degree) employed by a private community-based provider agency and supervised by a doctoral-level clinician. All members of the MST team completed a standard 5-day MST training curriculum and a 1.5-day supplemental training specific to working with youth with sexual behavior problems and their families. As per standard MST quality assurance procedures (Schoenwald, 2008), weekly supervision sessions were held on site and separate weekly consultation sessions were held via conference calls with MST expert consultants (the first and fourth authors).

The TAU treatment groups were led by seven treatment probation officers (four with master’s and three with bachelor’s degrees). The master’s-level treatment probation officers also held clinical licenses, and all treatment probation officers completed a certification course for treating JSO. The treatment probation officers received group supervision approximately twice per month from a master’s-level supervisor, who was licensed and experienced. All treatment probation officers earned a minimum of 20 annual continuing education units.

Outcome Measures

As noted previously, this report focuses on the sustainability of favorable MST outcomes reported at the 1-year follow-up as well as rearrest from baseline through a 2-year follow-up. To attenuate the risk that justice-involved youth might minimize their reports of inappropriate or illegal behavior, key outcomes were evaluated via multiple sources. Thus, problem sexual behaviors were assessed by youth self-report, parent report, and juvenile justice and criminal records, while general delinquent behavior was assessed by youth self-report and archival records. Other important but less central outcomes (i.e., youth substance use and out-of-home placements) were evaluated via a single source, reflecting the need to balance study resource capacity and participant time against the ideal of fully multi-modal, multi-respondent assessment protocols. There is no reason to suspect that participant baseline responses varied by condition, given that all youth were mandated to treatment and involved in the same juvenile justice system.

Problem sexual behavior

Youth problem sexual behaviors were assessed with the youth-report and caregiver-report versions of the Adolescent Clinical Sexual Behavior Inventory (ACSBI; Friedrich, Lysne, Sim, & Shamos, 2004), a 45-item instrument that measures inappropriate or concerning sexual behaviors. Items are measured on a 3-point scale from not true (0) to very true (2). The response time for the ACSBI was originally “past 12 months” and this was altered to “past 3 months” for consistency with other measures (see below). The ACSBI has been validated with samples of sexually abused and non-abused youth (coefficient alphas ranging from .65 to .81; Friedrich et al., 2004). Initial factor analysis suggested five subscales, including Sexual Knowledge/Interest (e.g., shows off their skin or body parts), Concerns About Appearance (e.g., is unhappy with their looks), Fear (e.g., has no friends of the opposite sex), Sexual Risk/Misuse (e.g., you are worried about your sexual behavior), and Divergent Sexual Interests (e.g., peeps into windows or tries to see others in the bathroom). Only the latter two of these subscales were considered most relevant to this study, given their relative focus on inappropriate sexual behaviors. The youth- and caregiver-report versions of the Divergent Sexual Interest subscale include nine and five items, respectively. The youth- and caregiver-report versions of the Sexual Risk/Misuse subscale include 8 and 10 items, respectively. For the three assessment points examined in the present paper (i.e., baseline, 18, and 24 months), small to moderate correlations were observed between the youth- and caregiver report versions of the Divergent Sexual Interest subscale (r-values ranged from .08 to .38) and the Sexual Risk/Misuse subscale (r-values ranged from .21 to .38). At baseline, 18, and 24 months, the coefficient alphas were .69, .78, and .58 (caregiver-report) and .35, .64, and .46 (youth-report) for the Divergent Sexual Interest subscale. The alphas were .81, .68, and .83 (caregiver-report) and .36, .71, and .70 (youth-report) for the Sexual Risk/Misuse subscale.

Delinquency

Youth criminal behavior was measured by the Self-Report Delinquency scale (SRD; Elliott, Huizinga, & Ageton, 1985) and arrest records. The SRD is a well-validated measure (Thornberry & Krohn, 2000) that assesses self-reported criminal and delinquent acts during the past 90 days. The 35-item general delinquency subscale was used in the present study and the coefficient alphas at baseline, 18, and 24 months were .86, .57, and .72, respectively. In addition, new arrests were identified from juvenile and adult records from city, state, and federal criminal justice sources. Statutory offenses, traffic violations, probation violations, and sex offender registry violations were excluded from analyses.

Substance use

Frequency of youth substance use across the past 90 days was assessed with 16 items from the Personal Experience Inventory (PEI; Winters & Henley, 1989), a reliable and well-validated instrument (Stinchfield & Winters, 1997). Each item assessed a different substance (e.g., marijuana, cocaine, heroin, alcohol). In the present study, only one youth reported use of any substance other than marijuana or alcohol. Thus, only the marijuana and alcohol use items were considered, and they were tested as separate outcomes in the analysis.

Out-of-home placements

During each month of participation, caregivers indicated whether the youth’s physical placement and/or guardianship had changed since the previous month. If so, the nature of the change was recorded. For the current study, youth were considered to have experienced an out-of home placement if they were placed in any type of incarceration setting (e.g., prison; n = 20), treatment setting (e.g., residential treatment center; n = 5), or supervised living facility (e.g., foster care; n = 8) in year 2.

Statistical Analyses

Because of the high proportion of “zero” responses, scores on all outcome measures were dichotomized. For the ACSBI, SRD, PEI, and out-of-home placement outcomes, data from the 18- and 24-month assessments were combined to reflect any endorsement of the outcome during the 2-year follow up. These data were then analyzed using hierarchical logistic regression. For the ACSBI, SRD, and PEI, the baseline score was entered in step 1 and a dichotomous indicator for intervention condition (1 = MST, 0 = TAU) was entered in step 2 to examine whether there was a treatment effect on the outcome during year 2 after accounting for baseline status. Baseline data were not available for out-of-home placements. Thus, the model examining this outcome only included the indicator for intervention condition. In light of the unidirectional hypotheses (i.e., determining whether favorable outcomes at 1 year were sustained at 2 years), one-tailed tests of significance were used for these models. Regarding arrests, data were aggregated to reflect any arrest from study recruitment through the 2-year follow-up and analyzed using logistic regression. A baseline indicator was entered in step 1 representing any lifetime arrest prior to recruitment (other than the index sexual offense). The treatment indicator was entered in step 2 to examine whether there was a treatment effect, and a two-tailed test of significance was used for the arrest model, as these data had not been examined previously.

Results

Descriptive statistics for the outcomes prior to and following dichotomization are presented in Tables 1 and 2. Results from the regression models are presented in Table 3. Results from analyses (not shown) that included data from the three female participants were not substantively different from those reported below. Previously reported (Letourneau et al., 2009) independent samples t-tests and chi-square analyses identified no statistically significant between-groups differences on type of index offense, presence of prior offenses, or demographic variables at baseline, supporting the effectiveness of the randomization process.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for the Youth and Caregiver-Report Outcomes

| Baseline | Year 2 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Raw | Binary | Raw | Binary | |||||||

| Outcome | Source | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| ACSBI Divergent | Caregiver | MST | 2.06 | 2.71 | 0.78 | 0.41 | 1.66 | 2.63 | 0.45 | 0.50 |

| Sexual Interests | TAU | 1.95 | 2.20 | 0.69 | 0.47 | 2.25 | 3.52 | 0.55 | 0.50 | |

| Youth | MST | 0.35 | 0.67 | 0.26 | 0.44 | 0.45 | 1.18 | 0.19 | 0.40 | |

| TAU | 0.28 | 0.67 | 0.21 | 0.41 | 0.58 | 1.03 | 0.34 | 0.48 | ||

| ACSBI Sexual | Caregiver | MST | 0.89 | 2.29 | 0.32 | 0.47 | 0.63 | 1.60 | 0.21 | 0.41 |

| Risk/Misuse | TAU | 0.74 | 1.82 | 0.21 | 0.41 | 0.64 | 2.47 | 0.17 | 0.38 | |

| Youth | MST | 1.23 | 1.46 | 0.57 | 0.50 | 1.32 | 2.09 | 0.39 | 0.49 | |

| TAU | 1.09 | 1.30 | 0.55 | 0.50 | 2.06 | 2.94 | 0.53 | 0.50 | ||

| SRD Delinquency | Youth | MST | 5.92 | 11.25 | 0.74 | 0.44 | 6.29 | 18.47 | 0.45 | 0.50 |

| TAU | 6.66 | 26.25 | 0.52 | 0.50 | 6.74 | 12.59 | 0.60 | 0.49 | ||

| PEI Marijuana | Youth | MST | 1.64 | 7.51 | 0.23 | 0.42 | 2.95 | 12.05 | 0.29 | 0.46 |

| TAU | 2.43 | 12.21 | 0.17 | 0.38 | 8.45 | 22.55 | 0.27 | 0.45 | ||

| PEI Alcohol | Youth | MST | 0.73 | 2.94 | 0.21 | 0.41 | 2.27 | 11.41 | 0.30 | 0.46 |

| TAU | 0.22 | 0.77 | 0.12 | 0.33 | 3.82 | 13.66 | 0.30 | 0.46 | ||

| Placementa | Caregiver | MST | -- | -- | -- | -- | 309.46 | 89.64 | 0.14 | 0.35 |

| TAU | -- | -- | -- | -- | 323.18 | 80.82 | 0.28 | 0.45 | ||

Note. N = 124; ACSBI = Adolescent Clinical Sexual Behavior Inventory; SRD = Self-Report Delinquency scale, PEI = Personal Experiences Inventory; MST = multisystemic therapy; TAU = treatment as usual.

Data reflect days in out-of-home placement settings.

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics for the Arrest Outcome at Baseline and from Baseline through Year 2

| Baselinea | Baseline-Year 2 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Raw | Binary | Raw | Binary | |||||

| Outcome | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD |

| Arrests | ||||||||

| MST | 0.85 | 1.66 | 0.35 | 0.48 | 2.36 | 3.56 | 0.52 | 0.50 |

| TAU | 0.66 | 1.38 | 0.28 | 0.45 | 2.59 | 4.41 | 0.50 | 0.50 |

Note. N = 124.

Data represent lifetime arrests prior to recruitment (other than the index sexual offense).

Table 3.

Final Logistic Regression Models

| Outcome | Source | B | SE | W | OR | CI (95%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACSBI Divergent | Caregiver | Baseline status | 1.55 | 0.48 | 10.36*** | 4.71 | [1.83,12.09] |

| Sexual Interests | Condition | −0.68 | 0.41 | 2.79* | 0.51 | [0.23,1.13] | |

| Youth | Baseline status | 0.86 | 0.47 | 3.28* | 2.35 | [0.93,5.94] | |

| Condition | −0.86 | 0.44 | 3.83* | 0.42 | [0.18,1.00] | ||

| ACSBI Sexual | Caregiver | Baseline status | 0.86 | 0.49 | 3.08* | 2.36 | [0.91,6.16] |

| Risk/Misuse | Condition | 0.30 | 0.48 | 0.39 | 1.35 | [0.53,3.46] | |

| Youth | Baseline status | 0.53 | 0.38 | 1.90 | 1.69 | [0.80,3.57] | |

| Condition | −0.65 | 0.38 | 2.96* | 0.52 | [0.25,1.09] | ||

| SRD Delinquency | Youth | Baseline status | 0.84 | 0.42 | 4.07* | 2.31 | [1.02,5.23] |

| Condition | −0.90 | 0.40 | 4.94* | 0.41 | [0.19,0.90] | ||

| PEI Marijuana | Youth | Baseline status | 1.39 | 0.47 | 8.56*** | 4.00 | [1.58,10.16] |

| Condition | −0.00 | 0.43 | 0.00 | 1.00 | [0.43,2.31] | ||

| PEI Alcohol | Youth | Baseline status | 1.05 | 0.51 | 4.29* | 2.85 | [1.06,7.70] |

| Condition | −0.11 | 0.41 | 0.07 | 0.90 | [0.40,2.01] | ||

| Placement | Caregiver | Condition | −0.85 | 0.47 | 3.34* | 0.43 | [0.17,1.06] |

| New Arrests | Records | Baseline status | 1.47 | 0.43 | 11.76*** | 4.37 | [1.88,10.14] |

| Condition | −0.04 | 0.38 | 0.01 | 0.96 | [0.45,2.02] |

Note. N = 124; W = Wald statistic; OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval; ACSBI = Adolescent Clinical Sexual Behavior Inventory; SRD = Self-Report Delinquency scale, PEI = Personal Experiences Inventory; for the condition variable, TAU = 0 and MST = 1.

p < .05.

p < .001.

Problem Sexual Behaviors

During the second year of follow-up, youth and caregivers in the MST condition continued to report fewer problem sexual behaviors than did counterparts in the TAU condition on three of four measures. Specifically, after accounting for baseline status, youth and caregivers in the MST condition were significantly less likely than their counterparts in the TAU condition to report any Divergent Sexual Interest, and youth in the MST condition were significantly less likely to report any Sexual Risk/Misuse.

Delinquency

On the SRD, youth in the MST condition were significantly less likely than youth in the TAU condition to report any criminal behavior in year 2, after accounting for baseline status. Regarding rearrests, from baseline to the 2-year follow-up, there were just four sexual offenses, which are too few to support separate analysis of this important outcome. On the other hand, approximately half of the sample experienced at least one arrest for a nonsexual offense during the 2-year follow-up. There was no between-groups difference on this outcome.

Substance Use

The reduction in substance use that favored youth in the MST condition during the first year of follow-up was no longer sustained during the second year.

Out-of-Home Placements

The between-groups difference in youth who received an out-of-home placement during the first year of follow-up was sustained during the second year. Specifically, caregivers in the MST condition were significantly less likely than caregivers in the TAU condition to report placement of their youth in year 2.

Discussion

With one exception, the results support the capacity of MST to sustain favorable clinical changes among JSO through a 2-year follow-up. Specifically, treatment effects regarding decreased problem sexual behavior, self-reported delinquency, and out-of-home placements were sustained. Importantly, these results were obtained by practitioners working within a community-based provider agency. Thus, the favorable results for JSO obtained in MST efficacy trials were extended, in part, to clinical practice in real world community treatment settings. Such findings support efforts to transport MST interventions for JSO.

In contrast with expectations, MST effects on rearrest were not observed. This result conflicts with the findings of many MST randomized trials with serious juvenile offenders (Henggeler, 2011). In other effectiveness studies that found attenuated effects on recidivism (i.e., Henggeler, Melton, Brondino, Scherer, & Hanley, 1997; Sundell et al., 2008), therapist fidelity to MST treatment principles (i.e., treatment adherence) has been both low and inversely correlated with rearrest. As reported in an evaluation of 1-year outcomes (Letourneau et al., 2009), average MST therapist fidelity scores for this trial were about .7 SD below those of typical MST practitioners working in community settings. In addition, fidelity scores were inversely correlated with arrests during years 1 and 2 (r = −.18), although not significantly (p = .15). Although the MST intervention was adapted to better account for working with JSO and their families, a standard MST fidelity rating was used, which might not have adequately captured the full range of therapist behaviors and which could account for the lower than expected ratings. Lower fidelity to standard MST, even in the presence of good fidelity to the adapted model, might also have accounted for failure to attain differences in arrests for nonsexual offenses. That is, therapists might have been more strongly focused on preventing future sexual offenses and focused less than usual on prevention of general delinquency. Future effectiveness research should incorporate measures of fidelity specific to adaptations.

Several study limitations are relevant. In comparison to other MST trials, youth in this study were less delinquent (i.e., 62% of the sample had no prior nonsexual offenses) and endorsement of problem behaviors and substance use was low. Relatedly, the measure of substance use was limited to just two items and obtained only via youth self-report. Likewise, out-of-home placements were obtained only via parent report and those results would be strengthened if replicated based on official data. Moreover, the ACSBI youth-reported Divergent Sexual Interests subscale was characterized by low internal reliability, particularly at baseline when youth report might have been most guarded given the recency of juvenile justice consequences. However, similar treatment effects were observed on the youth- and caregiver-report versions of this scale, providing some evidence of concurrent validity. Nevertheless, findings on this scale should be interpreted with caution. Another limitation is that the ACSBI does not capture the full range of problematic or illegal youth sexual behaviors. External validity might be limited due to the exclusion of a small portion (5%) of eligible youth who were sent to restrictive placements and selection of participants from a single urban area. In addition, with the low base rate of sexual recidivism observed here and by other researchers (see Fortune & Lambie, 2006), a longer follow-up is needed that extends through young adulthood when recidivism risk peaks (Loeber & Farrington, 2000). Study strengths include use of a randomized design, measurement of key outcomes from multiple perspectives, and reasonable recruitment rates and high participant retention rates. The investigators’ methods for recruitment and retention, refined across dozens of RCTs, included (1) meeting participants at times (e.g., evenings, weekends) and places (e.g., homes, other community locations) convenient to their schedules; (2) following up with participants as many times as needed to schedule sessions (vs. imposing arbitrary contact limits) and with sensitivity to their life circumstances (e.g., not when preoccupied by other stressors); (3) training research assistants to avoid taking scheduling difficulties (e.g., missed appointments, unreturned or intentionally dropped calls) personally and to remain professional and positive whenever interacting with participants; and (4) providing reasonable compensation to participants for their time.

In conclusion, youth treated with MST remained at significantly lower risk of out-of-home placement through the second year of follow-up relative to their TAU counterparts. Further, in contrast to youth in the TAU condition, those who received MST continued to achieve significantly greater improvement regarding problem sexual behavior and self-reported delinquency. These results suggest that an intensive, family- and community-based intervention can protect youth who have sexually offended from disruptive and costly placements and achieve significantly greater clinical improvement relative to typical treatment services.

Acknowledgments

This article was supported by National Institute of Mental Health Grant R01MH65414. Scott W. Henggeler is a board member and stockholder of MST Services LCC, the Medical University of South Carolina-licensed organization that provides training in MST. Charles M. Borduin is a board member of MST Associates, LLC, the organization that provides training in MST for youth with problem sexual behaviors.

We sincerely thank the many families that participated in this project as well as the clinical and research teams. We are especially grateful for the collaboration with the Cook County State’s Attorneys Office, the Circuit Court of Cook County and Juvenile Probation and Court Services.

Contributor Information

Elizabeth J. Letourneau, Johns Hopkins University

Scott W. Henggeler, Medical University of South Carolina

Michael R. McCart, Medical University of South Carolina

Charles M. Borduin, University of Missouri

Paul A. Schewe, University of Illinois-Chicago

Kevin S. Armstrong, Medical University of South Carolina

References

- Borduin CM, Henggeler SW, Blaske DM, Stein R. Multisystemic treatment of adolescent sexual offenders. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology. 1990;34:105–113. [Google Scholar]

- Borduin CM, Letourneau EJ, Henggeler SW, Saldana L, Swenson CC. Treatment manual for Multisystemic Therapy with juvenile sexual offenders and their families. Charleston, SC: Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Medical University of South Carolina; 2005. Unpublished manual. [Google Scholar]

- Borduin CM, Schaeffer CM, Heiblum N. A randomized clinical trial of multisystemic therapy with juvenile sexual offenders: Effects on youth social ecology and criminal activity. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77:26–37. doi: 10.1037/a0013035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott DS, Huizinga D, Ageton SS. Explaining delinquency and drug use. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, Ormrod R, Chaffin M. Juveniles who commit sex offenses against minors. Juvenile Justice Bulletin 2009 Dec; [Google Scholar]

- Friedrich WN, Lysne M, Sim L, Shamos S. Assessing sexual behavior in high-risk adolescents with the Adolescent Clinical Sexual Behavior Inventory (ACSBI) Child Maltreatment. 2004;9:239–250. doi: 10.1177/1077559504266907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortune C, Lambie I. Sexually abusive youth: A review of recidivism studies and methodological issues for future research. Clinical Psychology Review. 2006;26:1078–1095. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henggeler SW, Letourneau EJ, Chapman JE, Borduin CM, Schewe PA, McCart MR. Mediators of change for multisystemic therapy with juvenile sexual offenders. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77:451–462. doi: 10.1037/a0013971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henggeler SW. Efficacy studies to large-scale transport: The development and validation of MST programs. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2011;7:351–381. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032210-104615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henggeler SW, Melton GB, Brondino MJ, Scherer DG, Hanley JH. Multisystemic therapy with violent and chronic juvenile offenders and their families: The role of treatment fidelity in successful dissemination. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1997;65:821–833. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.5.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henggeler SW, Sheidow AJ, Lee T. Multisystemic treatment (MST) of serious clinical problems in youths and their families. In: Springer DW, Roberts AR, editors. Handbook of forensic mental health with victims and offenders: Assessment, treatment, and research. New York: Springer Publishing; 2007. pp. 315–345. [Google Scholar]

- Henggeler SW, Schoenwald SK, Borduin CM, Rowland MD, Cunningham PB. Multisystemic treatment of antisocial behavior in children and adolescents. 2. New York: Guilford Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Letourneau EJ, Henggeler SW, Borduin CM, Schewe PA, McCart MR, Chapman JE, Saldana L. Multisystemic therapy for juvenile sexual offenders: 1-year results from a randomized effectiveness trial. Journal of Family Psychology. 2009;23:89–102. doi: 10.1037/a0014352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loeber R, Farrington DP. Strategies and yields of longitudinal studies on antisocial behavior. In: Stoff DM, Brieling J, Maser JD, editors. Handbook of antisocial behavior. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 2000. pp. 125–139. [Google Scholar]

- McGrath R, Cumming G, Burchard B, Zeoli S, Ellerby L. Current Practices and Emerging Trends in Sexual Abuser Management: The Safer Society 2009 North American Survey. Brandon, Vermont: Safer Society Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Schoenwald S. Toward evidence-based implementation of evidence-based treatments: MST as an example. Journal of Child and Adolescent Substance Abuse. 2008;17:69–91. [Google Scholar]

- Stinchfield R, Winters KC. Measuring change in adolescent drug misuse with the Personal Experience Inventory (PEI) Substance Use and Misuse. 1997;32:63–76. doi: 10.3109/10826089709027297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundell K, Hansson K, Lofholm CA, Olsson T, Gustle LH, Kadesjo C. The transportability of MST to Sweden: Short-term results from a randomized trial of conduct disordered youth. Journal of Family Psychology. 2008;22:550–560. doi: 10.1037/a0012790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornberry TP, Krohn MD. The self-report method for measuring delinquency and crime. Criminal Justice. 2000;4:33–83. [Google Scholar]

- Winters KC, Henley G. The Personal Experiences Inventory. Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services; 1989. [Google Scholar]