Abstract

Neuronal synchronization supports different physiological states such as cognitive functions and sleep, and it is mirrored by identifiable EEG patterns ranging from gamma to delta oscillations. However, excessive neuronal synchronization is often the hallmark of epileptic activity in both generalized and partial epileptic disorders. Here, I will review the synchronizing mechanisms involved in generating epileptiform activity in the limbic system, which is closely involved in the pathophysiogenesis of temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE). TLE is often associated to a typical pattern of brain damage known as mesial temporal sclerosis, and it is one of the most refractory adult form of partial epilepsy. This epileptic disorder can be reproduced in animals by topical or systemic injection of pilocarpine or kainic acid, or by repetitive electrical stimulation; these procedures induce an initial status epilepticus and cause 1–4 weeks later a chronic condition of recurrent limbic seizures. Remarkably, a similar, seizure-free, latent period can be identified in TLE patients who suffered an initial insult in childhood and develop partial seizures in adolescence or early adulthood. Specifically, I will focus here on the neuronal mechanisms underlying three abnormal types of neuronal synchronization seen in both TLE patients and animal models mimicking this disorder: (i) interictal spikes; (ii) high frequency oscillations (80–500 Hz); and (iii) ictal (i.e., seizure) discharges. In addition, I will discuss the relationship between interictal spikes and ictal activity as well as recent evidence suggesting that specific seizure onsets in the pilocarpine model of TLE are characterized by distinctive patterns of spiking (also termed preictal) and high frequency oscillations.

Keywords: Entorhinal cortex, extracellular Ca2+ concentration, extracellular K+ concentration, GABA, high frequency oscillations, hippocampus, ictal discharges, interictal spikes, seizure onset, temporal lobe epilepsy

1. INTRODUCTION

Neuronal synchronization (i.e., the integrated activity of many neurons in one or more brain structures) is known to support different physiological states extending from cognitive functions to sleep, and it is mirrored by identifiable EEG patterns that range from the gamma rhythm to delta waves [1]. However, excessive neuronal synchronization is also the hallmark of epileptic discharges in both generalized and partial epileptic syndromes. The aim of this paper is to review the synchronizing mechanisms involved in the generation of epileptiform activity in the limbic system, which represents a set of brain structures that are closely involved in the pathophysiogenesis of temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE). The limbic system includes the hippocampus and parahippocampal areas such as the entorhinal cortex or the amygdala, all of which have well-developed anatomical and physiological mechanisms promoting neuronal synchronization [2, 3].

TLE is often associated to a typical pattern of brain damage known as mesial temporal sclerosis [2], and it is one of the most refractory form of partial epilepsy in adults [4–6]. Electrographic, behavioral, and histopathological findings similar to those seen in TLE patients can be reproduced in laboratory animals by topical or systemic injection of convulsants such as pilocarpine or kainic acid, or by repetitive electrical stimulation [7–9]. These procedures induce an initial status epilepticus and cause 1–4 weeks later a chronic condition of recurrent limbic seizures that are also poorly controlled by antiepileptic drugs [10]. Remarkably, a similar, seizure-free, latent period can be identified in TLE patients who suffered an initial insult in childhood (e.g., birth trauma, complex febrile convulsions, brain injury or meningitis) and develop partial seizures in adolescence or early adulthood [11, 12]. Hence, both in humans and in animal models, TLE is characterized by a seizure-free, latent period during which temporal lobe function is progressively altered until the appearance of the first seizure that marks the beginning of the chronic epileptic condition.

Specifically, I will focus here on three types of abnormal neuronal synchronization that are seen in TLE patients and in animal models mimicking this disorder both in vitro and in vivo: (i) interictal spikes; (ii) high frequency oscillations (HFOs, 80–500, at times 600 Hz); and (iii) ictal (i.e., seizure) discharges. In addition, I will discuss the relationship between interictal spikes and ictal activity and, in particular, recent evidence that suggests that specific seizure onsets in the rodent pilocarpine model of TLE are preceded by distinctive spiking patterns (also termed preictal) along with increased rates of specific types of HFOs. Given the large amount of studies covered here, only some original papers will be cited; however, I will provide the reader with some recent comprehensive reviews.

2. INTERICTAL SPIKES

Interictal spikes can be identified in the EEG of epileptic patients between seizures both in scalp and intracranial electrode recordings (Fig. 1A). They usually consist of a large-amplitude, rapid component (lasting 50–100 ms) usually followed by a slow wave (200–500 ms in duration). However, EEG recordings with cortical surface grids or with intracerebral electrodes have shown a large amount of variability in interictal discharge shape; even in the same patient, these events can include typical spikes, sharp waves, or bursts of fast spikes [13, 14]. Interictal spikes are not accompanied by any detectable clinical symptom but have been used to localize the epileptogenic zone in several partial epileptic disorders including TLE.

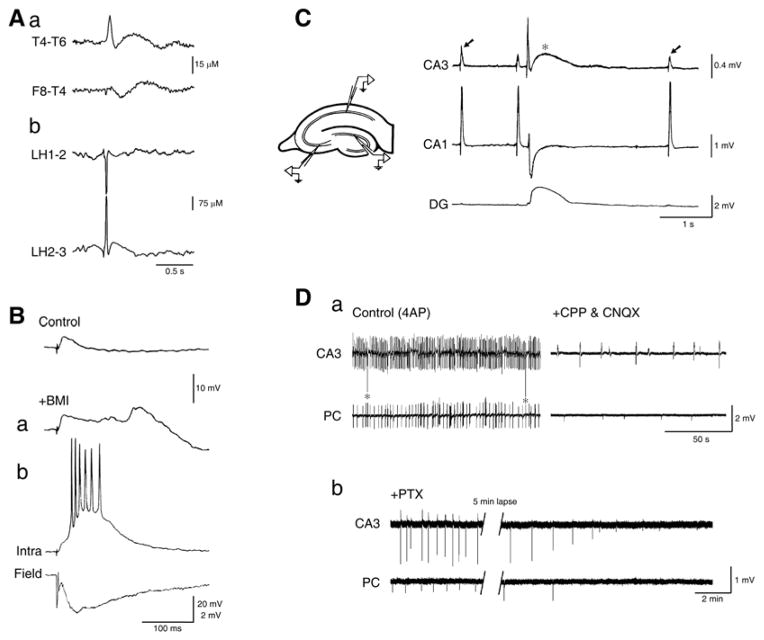

Fig. 1.

A: Electrographic features of interictal spikes recorded from a TLE patient with skull (a) and depth (b) electrodes; EEG recordings kindly provided by Drs. P. Perucca, F. Dubeau and J. Gotman at the Montreal Neurological Institute & Hospital. B: Changes of the responses generated by a neocortical neuron recorded intracellularly with a K-acetate-filled microelectrode in a human brain slice following single shock stimuli (triangle) under control conditions (Control) and during application of medium containing the GABAA receptor antagonist bicuculline methiodide (+BMI); trace in a was obtained shortly after the beginning of BMI application, and it shows the emergence of a late depolarizing potential that coincides with the time occupied under control conditions by a hyperpolarizing IPSP; traces shown in b, which were obtained after several minutes of BMI application, illustrate the interictal-like response recorded with a field electrode (Field), and the simultaneous intracellular paroxysmal depolarizing shift (Intra). C: Simultaneous field potential recordings obtained from an isolated hippocampal slice during application of 4-aminopyridine (4AP) show a pattern of “fast”, CA3-driven interictal spikes (arrows) that are not present in the dentate gyrus (DG) along with a “slow” interictal discharge (asterisk) that is recorded from all hippocampal regions. D: Simultaneous field potential recordings obtained from the CA3 subfield and the perirhinal cortex (PC) in a brain slice during application of 4AP (Control), after addition of glutamatergic receptor antagonists (CPP & CNQX), and after further addition of the GABAA receptor antagonist picrotoxin (PTX). Note that spontaneous field events continue to occur synchronously in the presence of glutamatergic receptor antagonists while the fast, CA3-driven interictal activity is abolished; note also that the glutamatergic-independent activity recorded from the CA3 subfield and the perirhinal cortex is abolished by picrotoxin.

Pioneering intracellular studies performed in acute in vivo models during the 1960s have demonstrated that interictal spikes recorded from cortical neurons located in epileptic foci induced by application of convulsants (such as penicillin) are mirrored by paroxysmal depolarizing shifts of the membrane potential leading to sustained action potential firing followed by a robust hyperpolarization [15–17]. These findings have been later confirmed by several experiments performed in hippocampal slices maintained in vitro during bath application of drugs that interfere with GABAA receptor signaling; these studies have demonstrated that in vitro interictal events are (i) initiated by enhancement of synaptic excitation due to weakening of inhibitory postsynaptic potentials (IPSPs), and (ii) rest on recurrent excitation and regenerative Ca2+ currents leading to the synchronous firing of a large number of principal cells [18–20]. These interictal spikes - which have been identified in several cortical areas including the hippocampus, the entorhinal cortex, and the neocortex (Fig. 1B) - depend on the activation of ionotropic glutamate receptors of the AMPA and NMDA subtypes, and are sustained by non-synaptic interactions such as intercellular gap junctions and ephaptic interactions [3].

Interictal activity, however, is also induced by applying solutions with specific ionic compositions that enhance neuronal excitability (e.g., high K+, low Cl−, or low Mg2+) or containing drugs that boost both glutamatergic and GABAergic synaptic transmission such as K+ channel blockers (e.g., tetraethylammonium or 4-aminopyridine, 4AP) [21]. In particular, 4AP can disclose two types of interictal spikes within the hippocampal formation [21]. The first type is characterized by frequently occurring interictal events that are driven by the CA3 network and are abolished by AMPA receptor antagonists (arrows in Fig. 1C). The second type consists of “slow” interictal spikes (asterisk in Fig. 1C) that continue to occur and to propagate during application of ionotropic glutamatergic receptor blockers but are abolished by GABAA receptor antagonists as well as by the μ-opioid receptor agonist [D-ala2, N-Me-Phe4,Gly5-ol]-enkephalin (DAGO), a pharmacological procedure that blocks the pre-synaptic release of GABA from interneurons [22] (Fig. 1D). These glutamatergic independent spikes have been identified in several structures (e.g., neocortex, amygdala, entorhinal, perirhinal, insular and piriform cortices) maintained in vitro both in the slice and in the isolated guinea pig brain preparation [21].

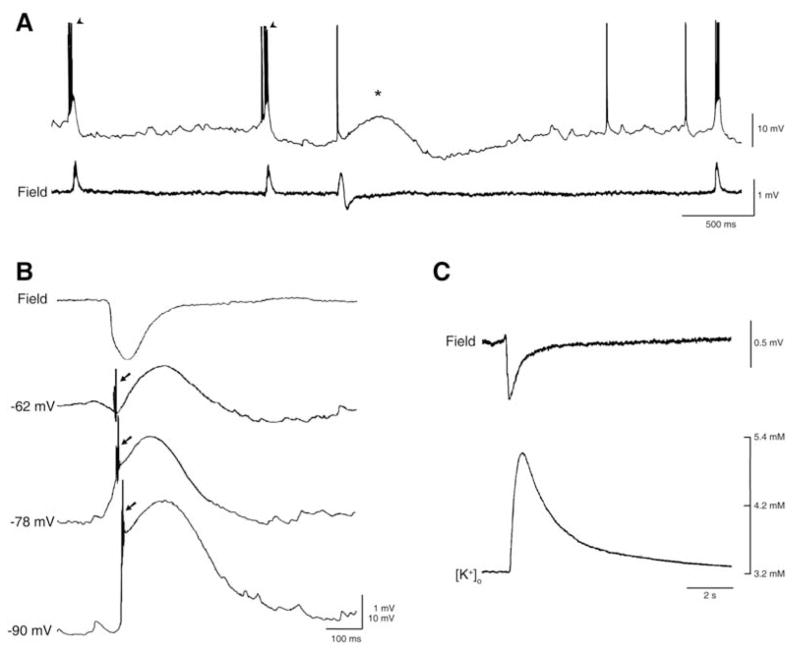

Intracellular recordings obtained from CA3 hippocampal pyramidal cells have revealed that CA3-driven interictal discharges induced by 4AP, like those recorded during application of GABAA receptor antagonists, are characterized by paroxysmal depolarizing shifts of the membrane potential that trigger action potential bursts (Fig. 2A, arrowheads). In contrast, the “slow” interictal spikes are associated to a long-lasting depolarization that can be preceded by a fast hyperpolarizing component depending upon the resting membrane potential of the recorded cell (Fig. 2A, asterisk). A similar intracellular event is recorded from principal neurons of the hippocampus, entorhinal cortex, and amygdala during concomitant application 4AP and ionotropic glutamatergic transmission blocker (Fig. 2B). It should be emphasized that these long-lasting depolarizations often trigger “spikes” of variable amplitude, presumably arising from axon terminals (arrows in Fig. 2B). We have proposed that axon terminal hyperexcitability - which has been documented in both in vivo [23, 24] and in vitro [25] models of epilepsy - depends on local, transient elevations in extracellular [K+] that accompany 4AP-induced, “slow” interictal discharges [26]. As illustrated in (Fig. 2C), these interictal spikes are accompanied by sizeable increases in extracellular [K+] even during blockade of ionotropic glutamatergic transmission [21].

Fig. 2.

A: Intracellular (K-acetate-filled microelectrode, Intra) and field potential (Field) recordings obtained from the CA3 subfield during 4AP application. Note that the intracellular counterpart of the “fast” interictal discharges recorded from a CA3 pyramidal cell consists of depolarizations that trigger bursts of fast action potentials while the counterpart of the “slow” interictal spike is characterized by a slow depolarization with a single fast action potential. B: Field and intracellular characteristics of the slow interictal discharge recorded from the CA3 subfield during application of 4AP and glutamatergic antagonists; note that depolarizing the resting membrane potential with steady current injection (−62 mV trace) discloses an initial hyperpolarizing component during which ectopic action potentials occur (arrow) as well as that similar ectopic “spikes” occur at more polarized membrane potentials (− 78 and −90 mV, arrows in both traces). Neurons recorded intracellularly in A and B were regularly firing, presumptive pyramidal cells. C: Simultaneous field potential and extracellular [K+] recordings of the glutamatergic independent interictal spike generated by entorhinal cortex neuronal networks during concomitant application of 4AP and glutamatergic antagonists; note that the extracellular [K+] increases up to approx. 5.0 mM from a resting concentration of 3.2 mM shortly after the negative peak of the field potential.

The diversity in interictal spiking identified in the in vitro 4AP model along with the heterogeneity of those recorded from TLE patients suggest that interictal events may be contributed by distinct and diverse neurobiological mechanisms. This hypothesis is supported by recent data obtained with single unit recordings from patients with medically intractable focal epilepsy [27]; interictal discharges in this study were characterized by heterogeneity in single unit activity both inside and outside the seizure onset zone, suggesting that they did not simply reflect a monolithic, hypersynchronous discharge as identified in acute animal experiments. In addition, such diversity supports the view that interictal discharges may play divergent functional roles with respect to ictogenesis (see section 5) and epileptogenesis. For instance, we have found in the pilocarpine model of TLE that interictal spikes have different shape, duration and rate of frequency when recorded during the latent period as compared with those occurring during the chronic epileptic phase [28]. In addition, Chauvière et al. [29] have recently described in the CA1 area two types of interictal spikes following pilocarpine or kainic acid-induced status epilepticus: the first (type 1) consisting of a spike followed by a wave, the second (type 2) characterized by a spike without wave; these authors found that type 1 events progressively decreased while the amount of type 2 increased during the latent period reaching their minimum/maximum values just before the occurrence of the first seizure. Therefore, interictal spikes undergo dynamic changes during the latent period and thus they may represent biomarkers of epileptogenesis.

3. HIGH FREQUENCY OSCILLATIONS

High frequency oscillations (HFOs, 80–500 Hz) constitute a rather novel category of neurophysiological activity that is fascinating neuroscientists, and particularly clinical and fundamental epileptologists. Oscillations at frequency higher than what is normally considered as standard in EEG recordings (i.e., < 70 Hz), were initially reported in physiological studies in which both gamma oscillatory events (up to 80 Hz) and ripples (80 to 200 Hz) were detected during visual perception, consummatory behaviors, slow-wave sleep, and memory consolidation [3, 21, 30–35]. The subsequent finding that HFOs occur in the EEG of epileptic patients [36] and animal models mimicking this condition has stimulated the interest for these oscillatory phenomena as possible biomarkers of epileptogenic neuronal networks [3, 21, 32–34].

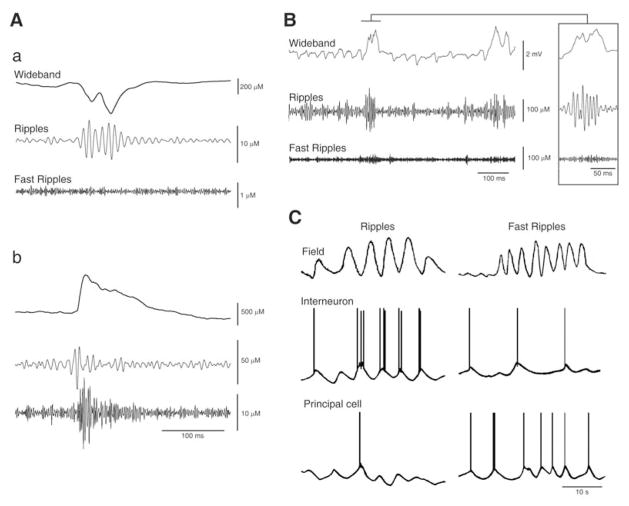

HFOs - which are not visible in standard intracranial EEG recordings and can only be extracted by amplifying the appropriately filtered signal - occur in epileptic patients in coincidence with interictal spikes but also in their absence [37, 38]. These pathological HFOs are usually categorized as ripples (80–200 Hz) and fast ripples (250–500 Hz). Several studies suggest that pathological HFOs reflect the activity of dysfunctional neural networks sustaining epileptogenesis, and they are now considered better markers than interictal spikes to identify seizure onset zones, independently of the underlying pathology [36]. Higher ratios of fast ripples to ripples are seen in TLE patients with smaller hippocampal volumes in magnetic resonance imaging along with histological lower neuron densities in dentate and Ammon’s horn regions [39, 40]. As illustrated in (Fig. 3A and 3B), ripple and fast ripple activity has been reported in depth electrode EEG recordings obtained from chronic epileptic rodents in coincidence with spikes occurring interictally as well as ictally [41–45].

Fig. 3.

A: EEG recordings obtained with a depth electrode placed in the entorhinal cortex of two pilocarpine-treated epileptic rats show HFOs in the ripple (a) and fast ripple (b) band occurring in coincidence with interictal spikes. B: EEG recording from the CA3 subfield of a pilocarpine-treated epileptic rat approx. 6 s after seizure onset shows the occurrence of a ripple (also illustrated at high time resolution in the inset). In both A and B panels the raw EEG signal (Wideband trace) was bandpass filtered in the 80–200 Hz (Ripples trace) and in the 250–500 Hz (Fast Ripples trace) frequency range. C: Model figure summarizing the hypothetical intracellular activity of a principal cell and of an interneuron during a ripple and a fast ripple. Note that the principal cell generates hyperpolarizing (presumably GABAergic) potentials during the ripple while it fires action potentials during the fast ripple; in contrast, the inhibitory interneuron fires in phase during the ripple but it does so randomly during the fast ripple.

Experimental studies have highlighted several mechanisms that may contribute to physiological and pathological HFOs; these include excitatory currents and recurrent inhibitory connectivity in combination with fast time scales of IPSPs, out-of-phase firing in neuronal clusters, and interneuronal coupling through gap junctions [3, 34]. The roles played by these mechanisms in pathologic HFOs are still under study but evidence obtained to date suggests that pathologic HFOs in the ripple band - like those recorded under physiological conditions [30, 31, 46, 47] (but see ref. 48 for a different interpretation) - may represent population IPSPs generated by principal neurons entrained by synchronously active interneuron networks (Fig. 3C). In contrast, fast ripples (250–500 Hz) may mirror the synchronous firing of abnormally active principal cells, and be independent of inhibitory neurotransmission (Fig 3C ever, both claims await firm experimental confirmation since, as already stated, some of this evidence was extrapolated from data obtained under physiological conditions or drawn from in vitro brain slices treated with convulsant drugs. Finally, in the very few studies in which in vivo single cell recordings were made in models of epilepsy [41–43], the relative contribution of interneurons versus principal cells to HFOs was not evaluated.

4. ICTOGENESIS

Ictogenesis (i.e., the process leading to seizure generation) comprises several cellular mechanisms that make neuronal networks generate prolonged periods of abnormal, hypersynchronous activity thus disrupting normal brain function. As shown in (Fig. 4A and 4B), the electrographic counterpart of a seizure (or ictal discharge) consists of a prolonged series of fast EEG transients that can vary in amplitude, and are easily distinguished from the background activity as well as from the interictal spikes; it should be emphasized that, electrographically, ictal discharges recorded from epileptic patients as well as from in vivo or in vitro animal models are remarkably similar. Intracellular recordings have demonstrated that ictal discharges are characterized by sustained depolarizations capped by action potential firing (Fig. 4C) and several studies have shown that ictal activity is dependent on glutamatergic neurotransmission (in particular the component that is mediated by the NMDA receptor) [52–54] along with persistent Na+ currents that are presumably fundamental to maintain the sustained action potential firing [3]. The latter mechanism is of importance since many of the most widely used antiepileptic drugs, including phenytoin, carbamazepine, lamotrigine and, perhaps, topiramate inhibit voltage-gated Na+ channels [55].

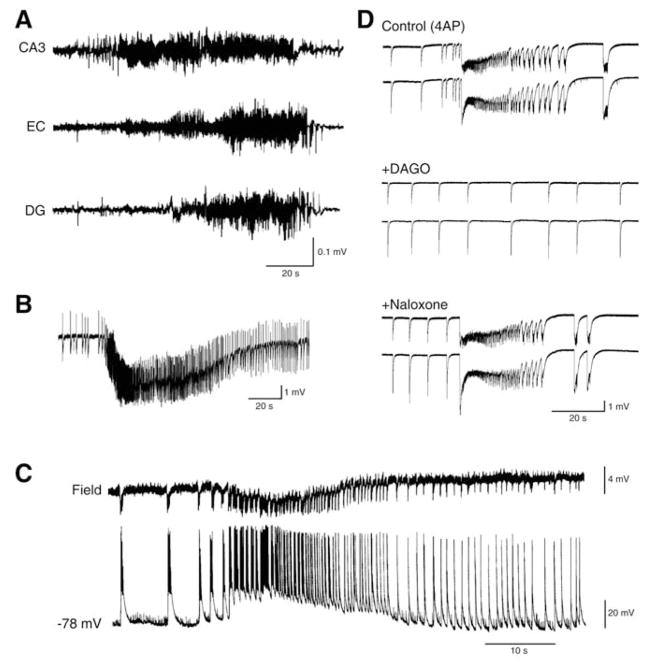

Fig. 4.

A: Seizure recorded with depth EEG electrodes placed in CA3, entorhinal cortex (EC) and dentate gyrus (DG) from a pilocarpine-treated epileptic rat. B: Electrographic seizure-like discharge recorded from the entorhinal cortex in a rat brain slice superfused with 4AP-containing medium. C: Simultaneous field (Field) and intracellular (−68 mV) recordings from the entorhinal cortex of a rat brain slice super-fused with Mg2+-free medium. The intracellular microelectrode was filled with KCl. D: Epileptiform activity recorded from two field recording electrodes placed in the rat cingulate cortex is modulated by μ-opioid receptors; note that the ictal activity induced by 4AP (Control) no longer persists after bath application of the μ-opioid agonist DAGO; this effect is reversed by the opioid antagonist naloxone.

Paradoxically, however, GABAA receptor-mediated mechanisms, and thus inhibitory networks, are also required for ictogenesis. As illustrated in (Fig. 4D), the ictal activity induced by 4AP in several limbic and extralimbic structures no longer persists after bath application of the μ-opioid agonist DAGO, an effect that is reversed by the μ-opioid antagonist naloxone. Similar anti-ictogenic effects have been reported to occur during application of GABAA receptor antagonists in several in vitro models of epileptiform synchronization [21]. As summarized in the review by Jefferys et al. [3], excessive inhibitory currents at the onset of and/or during seizure activity may overload the ability of the adult neuronal Cl− transporter KCC2 to maintain a low intracellular Cl− concentration thus disclosing depolarizing, and potentially excitatory, GABAA receptor-mediated conductances. This situation may be reinforced by HCO3−-mediated currents along with increases in extracellular [K+] which are caused by the activity of transporters responsible for reuptake of GABA and Cl− extrusion. Interestingly, it has been reported that GABAA receptor-mediated activity can be the sole synaptic mechanism contributing to the generation of in vitro seizure-like events under specific pharmacological manipulations [56]. The contribution of GABAA receptor-mediated signaling in ictogenesis is further discussed in section 5. Here, it should be emphasized that electrographic ictal-like discharges were rarely observed in the original intracellular studies performed in the 1960s in in vivo models in which acute foci were induced by application of the weak GABAA receptor antagonist penicillin [15, 16].

Non-synaptic mechanisms may also play central roles in ictogenesis. In line with this view, hippocampal brain slices maintained in vitro can generate prolonged discharges of population spikes during application of medium containing low or zero [Ca2+], i.e., an experimental procedure known to abolish synaptic transmission [57, 58]. It has been proposed that these seizure-like events depend on field (ephaptic) effects and gap junctions as well as on the accumulation of extracellular [K+] that occurs during the sustained discharge of Na+ action potentials; such increase in extracellular [K+] and its consequent spatial redistribution may also be responsible for the propagation of the ictal discharges within the hippocampal slice in this in vitro model of epileptiform synchronization. Non-synaptic mechanisms are presumably operative during normal synaptic transmission. However, and even more relevant for their role in epileptic discharge generation, it has been shown both in vitro and in vivo that extracellular [Ca2+] decreases during seizure activity to levels that should interfere with synaptic transmission [59–61].

5. INTERICTAL-ICTAL INTERACTIONS

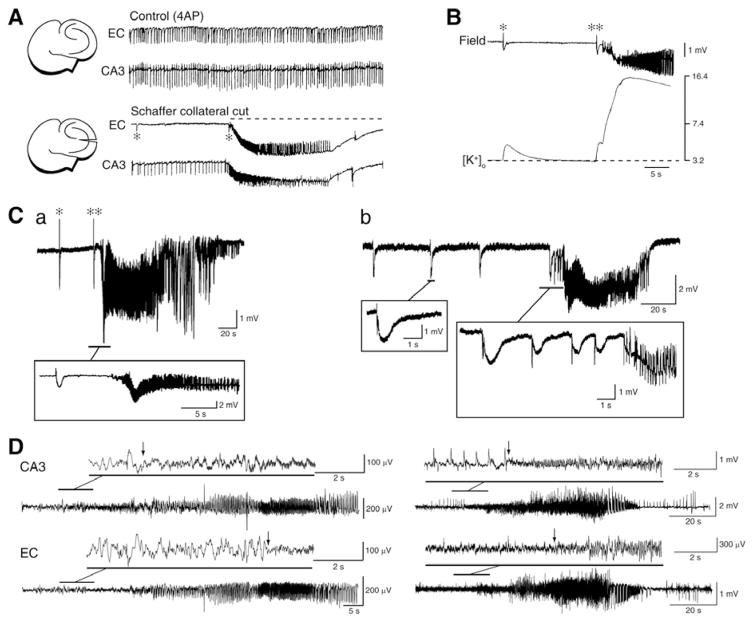

Experimental studies have shown that interictal and ictal discharges, in spite of their remarkable difference in duration, share similar intracellular (e.g., membrane depolarizations with intense action potential firing) and pharmacological characteristics (e.g., participation of ionotropic glutametergic and GABAergic conductances) (see sections 3 and 4). However, the rate of occurrence of interictal discharges in TLE patients does not change before seizure onset [62–64]. In addition, evidence obtained in both in vivo [65] and in vitro animal models (see for review ref. 21) indicate that interictal spiking may interfere with as well as facilitate ictogenesis. For instance, it has been shown that cutting the Schaffer collaterals in brain slices comprising interconnected hippocampus and entorhinal cortex networks during 4AP application, abolishes the propagation of CA3-driven interictal discharges to the entorhinal cortex and discloses slow interictal spikes and seizure-like events in this structure (asterisk and continuous line in (Fig. 5A), respectively) [21, 66, 67]. At the same time, however, ictal discharge is often preceded (and thus presumably initiated) by a slow interictal spike generated locally (double asterisks in Fig. 5B and 5Ca, see below). These findings, and in particular the ability of CA3-driven interictal activity to control ictogenesis in parahippocal areas, have been confirmed in rat brain slices in which structures such as perirhinal or insular cortices or the amygdala remained interconnected with the hippocampus proper [21]. The ability of hippocampal outputs to control ictogenesis may also be relevant in TLE, a disorder that is associated to CA3 and CA1 subfield damage [2]; according to this view a decrease in hippocampal output activity secondary to cell damage, should facilitate the generation of ictal discharges in parahippocampal structures [21, 66, 67].

Fig. 5.

A: Changes induced by Schaffer collateral cut on the epileptiform activity recorded from the CA3 and entorhinal cortex from a combined mouse brain slice. Under control conditions fast CA3-driven interictal activity is present in both areas; however, cutting the Schaffer collateral prevents CA3-driven interictal activity to propagate to the entorhinal cortex and uncovers ictal discharge (dotted line) along with slow interictal events (asterisks) in this area. B: Field and extracellular [K+] recordings during a slow interictal discharge and during the onset of a seizure-like discharge in the rat entorhinal cortex during 4AP application; note that the slow interictal spike (asterisk) is associated with an increase in extracellular [K+] that is smaller than what occurring in coincidence with the initial spike leading to ictal activity (double asterisk). Note also the much larger elevation in extracellular [K+] associated with the overt ictal discharge. C: Ictal discharges recorded from the entorhinal cortex in two brain slices that were superfused with 4AP containing medium. Note in a the occurrence of “slow” interictal discharges as well as that ictal onset is characterized by low-voltage oscillations at 10 Hz that follow by approx. 6 s a slow interictal event. In contrast, the onset of the ictal event shown in b is characterized by a pattern of acceleration of the “slow” interictal events. D: EEG recordings obtained from the hippocampus (CA3) and the entorhinal cortex (EC) of two pilocarpine-treated epileptic rats show onset patterns similar to those seen in vitro in C. These patterns consist of a spike followed by low-amplitude, high-frequency activity (asterisk in a) or of a series of spikes at approx. 1.5 Hz (asterisks in b) that are also followed by high frequency activity. Note that in both cases the high frequency activity (which signals the onset of the electrographic seizure) was observed first in the CA3 area.

A main player in controlling in vitro ictogenesis may relate to the ability of CA3-driven interictal spikes to hinder the transient elevations in extracellular [K+] that occur during the slow interictal events, and may be instrumental for ictal discharge onset (Fig. 5B). Therefore, CA3-driven interictal events should insure that GABA release during the slow interictal discharge is down-regulated thus controlling the associated elevations in extracellular [K+]. This hypothesis is further supported by experiments in which parahippocampal structures such as EC, amydala or insular cortex are stimulated at frequencies similar to those of CA3-driven interictal spikes (i.e., at 0.5–1.0 Hz) [21, 67]. Clinical studies have indeed shown that low frequency stimulation - delivered through transcranial magnetic or deep-brain electrical procedures - can reduce seizures in epileptic patients not responding to conventional antiepileptic therapy [68–71].

A relationship between interictal and ictal activity becomes, however, clear when addressing the dynamic changes in spiking seen at seizure onset. This type of activity is also identified as “preictal” in the literature; however this term may be erroneous since auras are seen in epileptic patients during this stage of the electrographic seizure and thus these spikes may reflect the beginning of the seizure rather than a preceding pattern. Indeed, over the last decade, clinical studies have categorized seizures occurring in TLE patients according to their onset pattern as (i) low-voltage fast-onset (LVF) seizures that are initiated by an isolated spike and (ii) hypersynchronous-onset (HYP) seizures that are heralded by repeated spiking [72–75]. Moreover, it has been proposed that HYP seizures may occur in TLE patients presenting with pronounced and restricted hippocampal atrophy, while LVF seizures are observed when more diffuse neuronal loss is present [74]. These two seizure onset types, which are also recorded in animal models both in vitro (Fig. 5C) [76–78] and in vivo (Fig. 5D) [42, 45], suggest that the spiking dynamics occurring at the onset of a seizure may mirror different pathophysiological mechanisms. In line with this view, we have discovered in pilocarpine-treated epileptic rats that ripples and fast ripples have different patterns of occurrence before as well as during LVF or HYP seizures suggesting that they may play specific roles in their initiation and maintenance [45]. Specifically, by recording the EEG from several limbic areas we have found that progression from interictal to ictal activity in LVF seizures is characterized in seizure onset zones by higher ripple rates compared to fast ripples and by a significant increase over time of ripples. On the contrary, interictal to ictal discharge transition in HYP seizures is typified by higher fast ripple compared to ripple rates and by an increase of fast ripple rates over time in both seizure onset zones and in regions of secondary spread.

6. CONCLUSIONS, NEW DEVELOPMENTS AND PERSPECTIVES

I have reviewed here the neuronal processes leading to epileptiform synchronization under acute pharmacological manipulations as well as in brains made chronically epileptic by experimental procedures such as the pilocarpine-induced status epilepticus. These data clearly underscore the importance of both synaptic and non-synaptic mechanisms as synchronizing players but some aspects remain intriguing and thus may deserve further attention. The first aspect relates to the identification of GABAA receptor signaling as an active contributor to neuronal network oscillations, interictal spiking and seizures. This mechanism, which at least in part rests on the ability of GABAA receptor activation to induce depolarizing conductances along with concomitant increases in extracellular [K+], is quite relevant for designing proper antiepileptic drugs, and it could represent an explanation for the poor efficacy of GABAergic anticonvulsants among infants. The second aspect concerns the contribution of synaptic mechanisms to neuronal synchronization during seizure discharges since, as discussed in section 4, it is well established that epileptiform activity is accompanied by decreases in extracellular [Ca2+] that are incompatible with efficient transmitter release. Indeed, more than thirty years ago, Pumain et al. [79] reported cospiquous decreases in extracellular [Ca2+] even during a single epileptic interictal spike. Yet, several in vitro studies (e.g., ref. 80) have shown that the same seizure-like discharges that are accompanied by decreased extracellular [Ca2+], are abolished by specific neurotransmitter receptor antagonists thus suggesting that they are contributed by synaptic conductances.

We have also reviewed recent studies suggesting that two main seizure onset types (i.e., LVF and HYP) occur in TLE patients as well as in the pilocarpine rat model. These findings suggest that progression to seizure discharge may reflect different cellular and pharmacological processes. Accordingly, the patterns of interictal (preictal) spiking seen during LVF and HYP onset seizures in epileptic animals were associated to increased rates of ripples and fast ripples that are presumably caused by the predominant activation of interneuron and principal cell networks, respectively. If confirmed in epileptic patients, this evidence could be relevant for identifying more efficacious, antiepileptic drug strategies aimed at interfering specifically with GABAergic (for LVF) and glutamatergic (for HYP) mechanisms. In addition, the specific increases in ripple and fast ripple rates seen during the preictal in LVF and HYP seizures, respectively, could be useful for developing seizure prediction tools. I must finally mention that this paper did not address the contribution of glial cells to epileptiform synchronization. Recent studies have indeed shown that astrocytes perform complex tasks that go well beyond well-known function of neurotransmitter uptake/recycling and extracellular K+ buffering [81–83]. In addition, dysfunction of glutamate transporters and of the astrocytic glutamate-converting enzyme, glutamine synthetase occur in the epileptic tissue suggesting that astrocyte dysfunction can lead to hyperexcitability, neurotoxicity and seizure generation in TLE patients [81–83].

Acknowledgments

The original work reviewed here was supported by the CIHR (Operating Grants 8109 and 74609), CURE and the Savoy Foundation. I thank Drs. M. D’Antuono, J. Gotman, R. Köhling, M. Lévesque, J. Louvel, G. Panuccio, P. Perreault and R. Pumain as well as Ms. P. Salami and R. Herrington for participating to the original experiments illustrated in this review.

ABBREVIATIONS

- 4AP

4-aminopyridine

- DAGO

[D-ala2, N-Me-Phe4,Gly5-ol]-enkephalin

- HFOs

High frequency oscillations

- HYP

Hypersynchronous-onset

- IPSPs

Inhibitory postsynaptic potentials

- LVF

Low-voltage fast-onset

- TLE

Temporal lobe epilepsy

Footnotes

Send Orders for Reprints to reprints@benthamscience.net

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The author(s) confirm that this article content has no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Niedermeyer E, Lopes Da Silva FH. Electroencephalography: Basic Principles, Clinical Applications, and Related Fields. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gloor P. The temporal lobe and limbic system. New York: Oxford University Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jefferys JGR, Jiruska P, de Curtis M, Avoli M. Limbic Network Synchronization and Temporal Lobe Epilepsy. In: Noebels JL, Avoli M, Rogawski MA, Olsen RW, Delgado-Escueta AV, editors. Jasper’s Basic Mechanisms of the Epilepsies [Internet] 4. Bethesda (MD): National Center for Biotechnology Information (US); 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Engel J, Jr, McDermott MP, Wiebe S, Langfitt JT, Stern JM, Dewar S, Sperling MR, Gardiner I, Erba G, Fried I, Jacobs M, Vinters HV, Mintzer S, Kieburtz K Early Randomized Surgical Epilepsy Trial (ERSET) Study Group. Early surgical therapy for drug-resistant temporal lobe epilepsy: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2012;307:922–930. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Semah F, Picot MC, Adam C, Broglin D, Arzimanoglou A, Bazin B, Cavalcanti D, Baulac M. Is the underlying cause of epilepsy a major prognostic factor for recurrence? Neurology. 1998;51:1256–1262. doi: 10.1212/wnl.51.5.1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wiebe S, Blume WT, Girvin JP, Eliasziw M. A randomized, controlled trial of surgery for temporal-lobe epilepsy. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:311–318. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200108023450501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ben-Ari Y. Limbic seizure and brain damage produced by kainic acid: mechanisms and relevance to human temporal lobe epilepsy. Neuroscience. 1985;14:375–403. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(85)90299-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Curia G, Longo D, Biagini G, Jones RS, Avoli M. The pilocarpine model of temporal lobe epilepsy. J Neurosci Methods. 2008;172:143–157. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2008.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gorter JA, van Vliet EA, Aronica E, Lopes da Silva FH. Progression of spontaneous seizures after status epilepticus is associated with mossy fibre sprouting and extensive bilateral loss of hilar parvalbumin and somatostatin-immunoreactive neurons. Eur J Neurosci. 2001;13:657–669. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2001.01428.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Löscher W, Köhling R. Functional, metabolic, and synaptic changes after seizures as potential targets for antiepileptic therapy. Epilepsy Behav. 2010;19:105–113. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2010.06.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.French JA, Williamson PD, Thadani VM, Darcey TM, Mattson RH, Spencer SS, Spencer DD. Characteristics of medial temporal lobe epilepsy: I. Results of history and physical examination. Ann Neurol. 1993;34:774–780. doi: 10.1002/ana.410340604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Salanova V, Markand ON, Worth R. Clinical characteristics and predictive factors in 98 patients with complex partial seizures treated with temporal resection. Arch Neurol. 1994;51:1008–1013. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1994.00540220054014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Curtis M, Avanzini G. Interictal spikes in focal epileptogenesis. Prog Neurobiol. 2001;63:541–567. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(00)00026-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Curtis M, Jefferys JGR, Avoli M. Interictal Epileptiform Discharges in Partial Epilepsy: Complex Neurobiological Mechanisms Based on Experimental and Clinical Evidence. In: Noebels JL, Avoli M, Rogawski MA, Olsen RW, Delgado-Escueta AV, editors. Jasper’s Basic Mechanisms of the Epilepsies [Internet] 4. Bethesda (MD): National Center for Biotechnology Information (US); 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matsumoto H, Ajmone-Marsan C. Cortical cellular phenomena in experimental epilepsy: interictal manifeststions. Exp Neurol. 1964;80:286–304. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(64)90025-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Prince D. Inhibition in ‘Epileptic’ neurons. Exp Neurol. 1968;21:307–321. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(68)90043-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ayala GF, Dichter M, Gumnit RJ, Matsumoto H, Spencer WA. Genesis of epileptic interictal spikes. New knowledge of cortical feedback systems suggests a neurophysiological explanation of brief paroxysms. Brain Res. 1973;52:1–17. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(73)90647-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dingledine R, Gjerstad L. Reduced inhibition during epileptiform activity in the in vitro hippocampal slice. J Physiol. 1980;305:297–313. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1980.sp013364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schwartzkroin PA, Prince DA. Changes in excitatory and inhibitory synaptic potentials leading to epileptogenic activity. Brain Res. 1980;183:61–76. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(80)90119-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Traub RD, Wong RK. Cellular mechanism of neuronal synchronization in epilepsy. Science. 1982;216:745–747. doi: 10.1126/science.7079735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Avoli M, de Curtis M. GABAergic synchronization in the limbic system and its role in the generation of epileptiform activity. Prog Neurobiol. 2011;95:104–132. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2011.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Madison DV, Nicoll RA. Enkephalin hyperpolarizes interneurons in the rat hippocampus. J Physiol. 1988;398:123–130. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1988.sp017033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gutnick MJ, Prince DA. Thalamocortical relay neurons: antidromic invasion of spikes from a cortical epileptogenic focus. Science. 1972;176:424–426. doi: 10.1126/science.176.4033.424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schwartzkroin PA, Mutani R, Prince DA. Orthodromic and antidromic effects of a cortical epileptiform focus on ventrolateral nucleus of the cat. J Neurophysiol. 1975;38:795–811. doi: 10.1152/jn.1975.38.4.795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stasheff SF, Hines M, Wilson WA. Axon terminal hyperexcitability associated with epileptogenisis in vitro. I. Origin of ectopic spikes. J Neurophysiol. 1993;70:961–975. doi: 10.1152/jn.1993.70.3.961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Avoli M, Methot M, Kawasaki H. GABA-dependent generation of ectopic action potentials in the rat hippocampus. Eur J Neurosci. 1998;10:2714–2722. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1998.00275.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Keller CJ, Truccolo W, Gale JT, Eskandar E, Thesen T, Carlson C, Devinsky O, Kuzniecky R, Doyle WK, Madsen JR, Schomer DL, Mehta AD, Brown EN, Hochberg LR, Ulbert I, Halgren E, Cash SS. Heterogeneous neuronal firing patterns during interictal epileptiform discharges in the human cortex. Brain. 2010;133:1668–1681. doi: 10.1093/brain/awq112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bortel A, Lévesque M, Biagini G, Gotman J, Avoli M. Convulsive status epilepticus duration as determinant for epileptogenesis and interictal discharge generation in the rat limbic system. Neurobiol Dis. 2010;40:478–489. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2010.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chauvière L, Doublet T, Ghestem A, Siyoucef SS, Wendling F, Huys R, Jirsa V, Bartolomei F, Bernard C. Changes in interictal spike features precede the onset of temporal lobe epilepsy. Ann Neurol. 2012;71:805–814. doi: 10.1002/ana.23549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Buzsáki G, Horváth Z, Urioste R, Hetke J, Wise K. High-frequency network oscillation in the hippocampus. Science. 1992;256:1025–1027. doi: 10.1126/science.1589772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ylinen A, Bragin A, Nádasdy Z, Jandó G, Szabó I, Sik A, Buzsáki G. Sharp wave-associated high-frequency oscillation (200 Hz) in the intact hippocampus: network and intracellular mechanisms. J Neurosci. 1995;15:30–46. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-01-00030.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Buzsáki G, Lopes da Silva F. High frequency oscillations in the intact brain. Prog Neurobiol. 2012;98:241–249. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2012.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Engel J, Jr, Lopes da Silva F. High-frequency oscillations - where we are and where we need to go. Prog Neurobiol. 2012;98:316–318. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2012.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jefferys JG, Menendez de la Prida L, Wendling F, Bragin A, Avoli M, Timofeev I, Lopes da Silva FH. Mechanisms of physiological and epileptic HFO generation. Prog Neurobiol. 2012;98:250–264. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2012.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bragin A, Engel J, Jr, Wilson CL, Fried I, Buzsáki G. High-frequency oscillations in human brain. Hippocampus. 1999;9:137–142. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1063(1999)9:2<137::AID-HIPO5>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jacobs J, Le Van P, Chander R, Hall J, Dubeau F, Gotman J. Interictal high-frequency oscillations (80–500 Hz) are an indicator of seizure onset areas independent of spikes in the human epileptic brain. Epilepsia. 2008;49:1893–1907. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2008.01656.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jacobs J, Staba R, Asano E, Otsubo H, Wu JY, Zijlmans M, Mohamed I, Kahane P, Dubeau F, Navarro V, Gotman J. High-frequency oscillations (HFOs) in clinical epilepsy. Prog Neurobiol. 2012;298:302–315. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2012.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Urrestarazu E, Chander R, Dubeau F, Gotman J. Interictal high-frequency oscillations (100–500 Hz) in the intracerebral EEG of epileptic patients. Brain. 2007;130:2354–2366. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ogren JA, Wilson CL, Bragin A, Lin JJ, Salamon N, Dutton RA, Luders E, Fileds TA, Fried I, Toga AW, Thompson PM, Engel J, Staba RJ. Three-dimensional surface maps link local atrophy and fast ripples in human epileptic hippocampus. Ann Neurol. 2009;66:783–791. doi: 10.1002/ana.21703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Staba R, Frighetto L, Behnke EJ, Mathern GW, Fields T, Bragin A, Ogren J, Fried I, Wilson CL, Engel J., Jr Increased fast ripple to ripple ratios correlate with reduced hippocampal volumes and neuron loss in temporal lobe epilepsy patients. Epilepsia. 2007;48:2130–2138. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2007.01225.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bragin A, Mody I, Wilson CL, Engel J., Jr Local generation of fast ripples in epileptic brain. J Neurosci. 2002;22:2012–2021. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-05-02012.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bragin A, Azizyan A, Almajano J, Wilson CL, Engel J., Jr Analysis of chronic seizure onsets after intrahippocampal kainic acid injection in freely moving rats. Epilepsia. 2005;46:1592–1598. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2005.00268.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bragin A, Benassi SK, Kheiri F, Engel J., Jr Further evidence that pathologic high-frequency oscillations are bursts of population spikes derived from recordings of identified cells in dentate gyrus. Epilepsia. 2011;52:45–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2010.02896.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lévesque M, Bortel A, Gotman J, Avoli M. High-frequency (80–500 Hz) oscillations and epileptogenesis in temporal lobe epilepsy. Neurobiol Dis. 2011;42:231–241. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2011.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lévesque M, Salami P, Gotman J, Avoli M. Two seizure onset types reveal specific patterns of high frequency oscillations in a model of temporal lobe epilepsy. J Neurosci. 32:13264–13272. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5086-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Le Van Quyen M, Bragin A, Staba R, Crepon B, Wilson CL, Engel J., Jr Cell type-specific firing during ripple oscillations in the hippocampal formation of humans. J Neurosci. 2008;28:6104–6110. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0437-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lapray D, Lasztoczi B, Lagler M, Viney TJ, Katona L, Valenti O, Hartwich K, Borhegyi Z, Somogyi P, Klausberger T. Behavior-dependent specialization of identified hippocampal interneurons. Nat Neurosci. 2012;15:1265–1271. doi: 10.1038/nn.3176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Maier N, Tejero-Cantero A, Dorrn AL, Winterer J, Beed PS, Morris G, Kempter R, Poulet JF, Leibold C, Schmitz D. Coherent phasic excitation during hippocampal ripples. Neuron. 2011;72:137–152. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dzhala VI, Staley KJ. Mechanisms of fast ripples in the hippocampus. J Neurosci. 2004;24:8896–8906. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3112-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Foffani G, Uzcategui YG, Gal B, de la Prida LM. Reduced spike-timing reliability correlates with the emercience of fast ripples in the rat epileptic hippocampus. Neuron. 2007;55:930–941. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.07.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ibarz JM, Foffani G, Cid E, Inostroza M, Menendez de la Prida L. Emergent dynamics of fast ripples in the epileptic hippocampus. J Neurosci. 2010;30:16249–16261. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3357-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Traynelis SF, Dingledine R. Potassium-induced spontaneous electrographic seizures in the rat hippocampal slice. J Neurophysiol. 1988;59:259–276. doi: 10.1152/jn.1988.59.1.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Köhr G, Heinemann U. Effects of NMDA antagonists on picrotoxin-, low Mg2+- and low Ca2+-induced epileptogenesis and on evoked changes in extracellular Na+ and Ca2+ concentrations in rat hippocampal slices. Epilepsy Res. 1989;4:187–200. doi: 10.1016/0920-1211(89)90003-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Löscher W, Hönack D. Anticonvulsant and behavioral effects of two novel competitive N-methyl-d-aspartic acid receptor antagonists, CGP 37849 and CGP 39551, in the kindling model of epilepsy. Comparison with MK-801 and carbamazepine. J Pharmcol Exp Ther. 1991;256:432–440. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mantegazza M, Curia G, Biagini G, Ragsdale DS, Avoli M. Voltage-gated sodium channels as therapeutic targets in epilepsy and other neurological disorders. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9:413–424. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70059-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Uusisaari M, Smirnov S, Voipio J, Kaila K. Spontaneous epileptiform activity mediated by GABA (A) receptors and gap junctions in the rat hippocampal slice following long-term exposure to GABA (B) antagonists. Neuropharmacology. 2002;43:563–572. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(02)00156-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jefferys JGR, Haas HL. Synchronized bursting of CA1 pyramidal cells in the absence of synaptic transmission. Nature. 1982;300:448–450. doi: 10.1038/300448a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Konnerth A, Heinemann U, Yaari Y. Non-synaptic epileptogenesis in the mammalian hippocampus in vitro. I. Development of seizure-like activity in low extracellular calcium. J Neurophysiol. 1986;56:409–423. doi: 10.1152/jn.1986.56.2.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pumain R, Menini C, Heinemann U, Louvel J, Silva-Barrat C. Chemical synaptic transmission is not necessary for epileptic seizures to persist in the baboon Papio papio. Exp Neurol. 1985;89:250–258. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(85)90280-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Heinemann U, Konnerth A, Pumain R, Wadman WJ. Extracellular calcium and potassium changes in chronic epileptic brain tissue. Adv Neurol. 1986;44:641–661. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Timofeev I, Steriade M. Neocortical seizures: initiation, development and cessation. Neuroscience. 2004;123:299–336. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2003.08.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lange HH, Lieb JP, Engel J, Jr, Crandall PH. Temporo-spatial patterns of pre-ictal spike activity in human temporal lobe epilepsy. EEG Clin Neurophysiol. 1983;56:543–555. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(83)90022-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gotman J. Relationships between interictal spiking and seizures: human and experimental evidence. Can J Neurol Sci. 1991;18:573–576. doi: 10.1017/s031716710003273x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gotman J, Marciani M. Electroencephalographic spiking activity, drug levels, and seizure occurrence in epileptic patients. Ann Neurol. 1985;17:597–603. doi: 10.1002/ana.410170612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Engel J, Ackermann R. Interictal EEG spikes correlate with decreased, rather than increased, epileptogenicity in amygdaloid kindled rats. Brain Res. 1980;190:543–548. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(80)90296-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Barbarosie M, Avoli M. CA3-driven hippocampal-entorhinal loop controls rather than sustains in vitro limbic seizures. J Neurosci. 1997;17:9308–9314. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-23-09308.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Avoli M, de Curtis M, Köhling R. Does interictal synchronization influence ictogenesis? Neuropharmacology. 2013;69:37–44. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2012.06.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tergau F, Naumann U, Paulus W, Steinhoff B. Low-frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation improves intractable epilepsy. Lancet. 1999;353:2209–2215. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)01301-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Theodore WH, Fisher RS. Brain stimulation for epilepsy. Lancet Neurol. 2004;3:111–118. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(03)00664-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Vonck K, Boon P, Achten E, De Reuck J, Caemaert J. Long-term amygdalo-hippocampal stimulation for refractory temporal lobe epilepsy. Ann Neurol. 2002;52:556–565. doi: 10.1002/ana.10323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yamamoto J, Ikeda A, Kinoshita M, Matsumoto R, Satow T, Takeshita K, Matsuhashi M, Mikuni N, Miyamoto S, Hashimoto N, Shibasaki H. Low-frequency electric cortical stimulation decreases interictal and ictal activity in human epilepsy. Seizure. 2006;15:520–527. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2006.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bartolomei F, Khalil M, Wendling F, Sontheimer A, Regis J, Ranjeva JP, Guye M, Chauvel P. Entorhinal cortex involvement in human mesial temporal lobe epilepsy: an electrophysiologic and volumetric study. Epilepsia. 2005;46:677–687. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2005.43804.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kahane P, Bartolomei F. Temporal lobe epilepsy and hippocampal sclerosis: lessons from depth EEG recordings. Epilepsia. 2010;51(Suppl 1):59–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2009.02448.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ogren JA, Bragin A, Wilson CL, Hoftman GD, Lin JJ, Dutton RA, Fields TA, Toga AW, Thompson PM, Engel J, Jr, Staba RJ. Three-dimensional hippocampal atrophy maps distinguish two common temporal lobe seizure-onset patterns. Epilepsia. 2009;50:1361–1370. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2008.01881.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Velasco AL, Wilson CL, Babb TL, Engel J., Jr Functional and anatomic correlates of two frequently observed temporal lobe seizure-onset patterns. Neural Plast. 2000;7:49–63. doi: 10.1155/NP.2000.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Avoli M, Panuccio G, Herrington R, D’Antuono M, de Guzman P, Lévesque M. Two different interictal spike patterns anticipate ictal activity in vitro. Neurobiol Dis. 2013;52:168–176. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2012.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Derchansky M, Jahromi SS, Mamani M, Shin DS, Sik A, Carlen PL. Transition to seizures in the isolated immature mouse hippocampus: a switch from dominant phasic inhibition to dominant phasic excitation. J Physiol. 2008;586:477–494. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.143065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zhang ZJ, Koifman J, Shin DS, Ye H, Florez CM, Zhang L, Valiante TA, Carlen PL. Transition to seizure: ictal discharge is preceded by exhausted presynaptic GABA release in the hippocampal CA3 region. J Neurosci. 2012;32:2499–2512. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4247-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Pumain R, Kurcewicz I, Louvel J. Fast extracellular calcium transients: involvement in epileptic processes. Science. 1983;222:177–179. doi: 10.1126/science.6623068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Avoli M, Louvel J, Kurcewicz I, Pumain R, Barbarosie M. Extracellular free potassium and calcium during synchronous activity induced by 4-aminopyridine in the juvenile rat hippocampus. J Physiol. 1996;493:707–717. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Haydon PG, Carmignoto G. Astrocyte control of synaptic transmission and neurovascular coupling. Physiol Rev. 2006;86:1009–1031. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00049.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Steinhäuser C, Seifert G, Bedner P. Astrocyte dysfunction in temporal lobe epilepsy: K+ channels and gap junction coupling. Glia. 2012;60:1192–1202. doi: 10.1002/glia.22313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Crunelli V, Carmignoto G. New vistas on astroglia in convulsive and non-convulsive epilepsy highlight novel astrocytic targets for treatment. J Physiol. 2013;591:775–785. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2012.243378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]