Abstract

The cochleovestibular (CV) nerve, which connects the inner ear to the brain, is the nerve that enables the senses of hearing and balance. The aim of this study was to document the morphological development of the mouse CV nerve with respect to the two embryonic cells types that produce it, specifically, the otic vesicle-derived progenitors that give rise to neurons, and the neural crest cell (NCC) progenitors that give rise to glia. Otic tissues of mouse embryos carrying NCC lineage reporter transgenes were whole mount immunostained to identify neurons and NCC. Serial optical sections were collected by confocal microscopy and were compiled to render the three dimensional (3D) structure of the developing CV nerve. Spatial organization of the NCC and developing neurons suggest that neuronal and glial populations of the CV nerve develop in tandem from early stages of nerve formation. NCC form a sheath surrounding the CV ganglia and central axons. NCC are also closely associated with neurites projecting peripherally during formation of the vestibular and cochlear nerves. Physical ablation of NCC in chick embryos demonstrates that survival or regeneration of even a few individual NCC from ectopic positions in the hindbrain results in central projection of axons precisely following ectopic pathways made by regenerating NCC.

Keywords: Ear, otic, neural crest, neuron, craniofacial, axon, cochlea, vestibular

Introduction

During embryogenesis the vertebrate inner ear begins as a simple flat otic placode that invaginates to become a spherical epithelial sac known as the otic vesicle (reviewed in (Bok et al., 2007; Chen and Streit, 2013; Groves and Fekete, 2012; Ladher et al., 2010; Schlosser, 2010)). This vesicle grows and remodels to form a complex structure of interlinked compartments known as the membranous labyrinth (Kopecky et al., 2012; Streeter, 1906). In mammals these compartments consist of a spiraling cochlea, which is the auditory organ, a saccule, utricle and three semicircular canals, which together form the vestibular system. These structures contains patches of mechano-sensory receptors that detect sound or gravity and motion, each of which is connected to the brain via the cochleovestibular (CV) nerve (reviewed in (Appler and Goodrich, 2011; Fekete and Campero, 2007; Yang et al., 2011)). The CV nerve originates initially during embryogenesis as a simple unified entity that progressively develops into an elaborate branching structure (Kopecky et al., 2012; Streeter, 1906). In mammals, the mature CV nerve is subdivided into distinct nerve trunks; a superior and inferior vestibular nerve, which together innervate the vestibular system, and a cochlear nerve, which innervates the auditory organ.

All peripheral nerves are composed of neurons supported by glial cells, and both cell types are important for nerve function (reviewed in (Hanani, 2005)). Peripheral nerve glia include Schwann cells, which support neuronal axons and neurites, and satellite cells, which surround and myelinate ganglionic neuronal cell bodies. As one of the cranial peripheral nerves, the CV nerve is likewise composed of both neurons and glia (Rosenbluth, 1962). These two cell types arise developmentally from distinct sources, the glial cells being derived from neural crest cell (NCC) progenitors (D'Amico-Martel and Noden, 1983; Harrison, 1924; Yntema, 1943b), while the neurons originate almost exclusively from the otic placode (Breuskin et al., 2010; D'Amico-Martel and Noden, 1983; van Campenhout, 1935), with the exception of rare neurons of the vestibular ganglia. The exclusive placodal derivation of CV neurons makes the nerve somewhat unique among cranial sensory nerves, most of which contain neurons derived from two sources, the sensory placodes and NCC (D'Amico-Martel and Noden, 1983). While experiments in amphibian, avian, and mammalian systems have each indicated CV neurons derive almost exclusively from placode progenitors, a recent study of transgenic lineage reporter mice has posed a contradictory scenario wherein NCC or a related population of migratory neuroepithelial cells give rise to a significant fraction of CV neurons and also to cells of the otic epithelium (Freyer et al., 2011).

The neuronal cells of the CV nerve develop by delaminating from the otic vesicle, proliferating and aggregating to form the CV ganglion (Altman and Bayer, 1982; Carney and Silver, 1983). As development proceeds CV neurons project central axons to the hindbrain and project peripheral neurites to sensory targets developing within the otic epithelium (reviewed in (Fritzsch, 2003). The glial cells of the CV nerve derive from NCC that emigrate from the hindbrain at the level of rhombomere 4 (R4) (D'Amico-Martel and Noden, 1983). Based on dye labeling analysis, CV neurons extend peripheral neurites to the developing vestibular sensory epithelium as early as embryonic day 11.5 (E11.5) and central axons to the hindbrain as early as E12.5 (Fritzsch, 2003; Matei et al., 2005). Maturation of CV neurons, as measured by final cell division, indicates vestibular and cochlear neurons mature at embryonic day E11.5 and E13.5, respectively (Matei et al., 2005; Ruben, 1967), earlier than the associated Schwann cell progenitors, which continue dividing up to the time of birth (Ruben, 1967).

A growing body of evidence suggests that interactions between glial and neuronal progenitors may be important for development of the CV nerve. In mouse, disturbance of ERBB2, a receptor that mediates neuron-glia interactions via the ligand Neuregulin 1 (reviewed in (Corfas et al., 2004)) compromises development of the CV nerve. Complete loss of ErbB2 severely disrupts formation of cranial nerves (Lee et al., 1995) but is lethal at E10.5 owing to cardiac defect. ErbB2 mutants rescued to later stages exhibit abnormalities in development of the CV nerve, including altered migration of neuronal cell bodies, abnormal targeting of peripheral neurites and reduced neuron number (Morris et al., 2006). Whereas the phenotype of ErbB2 mutants indicates that migration and targeting of CV neurons depends upon signaling interactions with NCC glial progenitors, the relatively normal development of CV nerves in embryos lacking Sox10, a transcription factor important for development of peripheral glial NCC, suggests otherwise (Breuskin et al., 2010). The reason for the differing effect of ErbB2 mutation versus Sox10 mutation is not yet clear, but, because Sox10 mutation results in loss of NCC glial progenitors after E10.5, the normal growth and guidance of CV neurons in those mutants may indicate that critical interactions occur earlier.

That interactions between NCC glial progenitors and neurons are important for development of cranial nerves is supported also by chick and zebrafish studies in which NCC are eliminated or signaling interactions between NCC and neurons is blocked. Molecularly blocking Semaphorin/Neuropilin signaling in chick disrupts NCC migratory pathways and impairs the inward movement of epibranchial placodal neurons (Osborne et al., 2005). In some studies ablation of NCC migration by physical or molecular methods in chick results in reduced numbers of neuroblasts migrating from epibranchial ganglia and abnormal projection of central axons (Begbie and Graham, 2001; Freter et al., 2013; Yntema, 1944), although other studies reported NCC removal did not disrupt formation of ganglia (Begbie et al., 1999). In zebrafish also elimination of specific sub-populations of cranial NCC disrupts formation of the epibranchial nerves (Culbertson et al., 2011).

Visualization of early developmental association between neuronal and glial progenitors of the facial ganglion in mouse and chick indicates that NCC form a corridor surrounding placodal neuroblasts (Freter et al., 2013). In mouse, genetic ablation of NCC causes some abnormalities in growth of peripheral projections of the facial nerve, but delamination of neuroblasts and formation of the ganglion is not impaired (Coppola et al., 2010).

Despite the many important insights regarding cranial sensory nerve development that have been made, owing to the dynamic remodeling and morphological complexity of the embryonic inner ear, many details of CV nerve formation remain obscure. To understand development of neuronal and glial progenitors in the embryonic CV nerve, we examined immunostained inner ears of mouse transgenic NCC lineage reporter embryos and chick embryos by confocal microscopy, compiling multiple optical sections into virtual 3D renderings of developing CV nerves. By this method we gain insight into the coordinated development of otic vesicle-derived neurons and NCC-derived glial cells of the CV nerve.

Materials and methods

Mice

Mouse strains utilized in this study included the following:

“Z/EG”, official name, Tg(CAG-Bgeo/GFP)21Lbe/J, Jax stock # 003920;

“R26R”, official name, FVB.129S4(B6)-Gt(ROSA)26Sortm1Sor/J, Jax stock # 009427,

“Wnt1Cre”, official name, Tg(Wnt1-cre)11Rth Tg(Wnt1-GAL4)11Rth/J, Jax stock #003829,

“6.5Pax3Cre”, novel stable transgenic Cre driver line in FVB/NJ background. Transgene contains 6.5kb NotI-HindIII fragment of genomic regulatory DNA 5’ of mouse Pax3 start site.

Images to emphasize embryo morphology

In order to enhance visualization of morphology of embryos stained for β-galactosidase activity, color images of β-galactosidase stained embryos were overlain onto greyscale images of same embryos stained for DAPI to label all cell nuclei. Imaging of whole embryos stained with DAPI or other nuclear fluorescent dye reveals details of embryo morphology not visible with white light, as previously described (Sandell et al., 2012). Overlay of color images of β-galactosidase stain embryos with greyscale image of embryo morphology yields improved visualization of β-galactosidase signal relative to embryonic structures.

Chick NCC ablation

Fertile chicken eggs (Gallus gallus domesticus) were preliminarily incubated at 37°C to allow embryos to develop to HH stage 8 to 9+ (6-9 somites). Eggs were then windowed and R4 NCC were ablated by microsurgical removal of the neural tube from R3 through R5. Operated embryos were re-sealed and allowed to continue development for an additional 24 or 48 hours.

Whole mount immunostain

For E10.5 mouse and chick, specimens were immunostained as whole embryo. For E11.5 mouse inner ear, embryo head specimens were bisected sagittally prior to immunostain to permit penetration of antibody and wash solutions. For E12.5 specimens, inner ears were isolated by dissection. Embryo specimens were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (formaldehyde) phosphate buffered saline (PBS), overnight at 4 °C, then washed in PBS and transferred (through a graded series) into 100% methanol. Tissues and embryos to be immunostained were permeabilized in Dent's bleach (MeOH:DMSO:30%H2O2, 4:1:1) for 2 h at room temperature, then washed with 100% methanol and transferred (through a graded series) into PBS. Blocking and antibody hybridization was performed in a buffer of 0.1M Tris pH7.5/0.15M NaCl. Non-specific antibody binding was blocked by two hour incubation with gentle rocking in buffer with 0.5% Perkin Elmer Block Reagent (FP1020), or alternatively 3% Bovine Serum Albumen. Primary antibody hybridization was performed in same blocking buffer overnight at 4 °C. Following primary antibody hybridization specimens were washed 5 × 1 h in PBS at room temperature. Secondary antibody hybridization was performed in blocking buffer overnight at 4 °C. Secondary antibody was removed by 3 X 20 min washes in PBS at room temperature. Specimens were stained with DAPI dilactate, 10 μg/ml in PBS, 10 min or longer at room temperature. Specimens were then transferred (through a graded series) into 100% methanol.

Antibodies

ISL1 antibody, 1/50, (39.4D5, Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank);

βIII neuronal tubulin antibody (TUJ1), 1/500, (MMS-435P or PRB-435P, Covance);

GFP antibody, 1/500, (A6455 Invitrogen/Molecular Probes);

HNK-1, 1/5, (supernatant from cultured HNK-1 cells, American Type Culture Collection);

Alexa Fluor 488, 1/300, (A21206 or A21042, Invitrogen/Molecular Probes);

Alexa Fluor 546, 1/300, (A11030, A10040, 10040, Invitrogen/Molecular Probes)

Whole mount confocal imaging of immunostained embryos and ear tissues

Tissue or embryos specimens that had been immunostained and dehydrated as described above were prepared for clearing by equilibrating through a second wash of 100% methanol to ensure complete dehydration. Specimens were then cleared with BABB (Benzyl Alcohol:Benzyl Benzoate, 1:2). Glass imaging wells were prepared by coating a Teflon O-ring with vacuum grease and affixing the ring to a glass depression slide. BABB cleared specimens were placed into prepared wells with the aid of UV light under a fluorescent stereo microscope to visualize the DAPI signal. Once specimens were place, the well was filled with BABB and a coverslip was adhered to the top of the O-ring with vacuum grease. Confocal images were captured on an upright Zeiss LSM510 Pascal equipped with a 405 nm laser. For each specimen, a z-stack of images was collected.

3D image rendering

Confocal z-stacks were rendered with the 3D image processing software IMARIS (Bitplane AG). For optically cropped images, individual image planes were manually cropped to omit non-ear tissues and to retain only the area of interest. The z-stack of cropped images was then rendered to reveal the 3D structure of the developing otic vesicle and CV nerve. For visualization of ganglion shape fluorescence signal was rendered as solid surfaces to generate shadows to enhance visualization of ganglion morphology.

Results

Imaging NCC in ear development

In order to assess the distribution of NCC during morphogenesis of the CV nerve we examined embryos in which NCC were marked by Cre recombinase activation of lacZ or GFP using the R26R (Soriano, 1999) or Z/EG (Novak et al., 2000) reporter strains. Wnt1 regulatory sequences drive expression in dorsal neural tube cells (Echelard et al., 1994), and the Wnt1Cre transgene , in combination with the R26R reporter irreversibly marks all NCC and derivatives by expression of lacZ (Chai et al., 2000). Consistent with many previous studies characterizing Wnt1Cre;R26R embryos, using this combination of Cre driver and reporter we observe extensive β-galactosidase activity in NCC and derivatives throughout the pharyngeal arches (Fig. 1 A). Similarly, the Wnt1Cre can be combined with the Z/EG reporter, which allows NCC to be visualized in conjunction with different cell types and molecular markers by double immunostaining for GFP and other molecules such as βIII neuronal tubulin, which labels neuronal axons and neurites (Fig. 1C). The Wnt1Cre driver works well to visualize all NCC, however, because NCC contribute so extensively to craniofacial development, with this pan-NCC Cre driver it can be difficult to visualize morphogenesis of specific tissues and structures in the head and face.

Figure 1. Mouse Cre driver;reporter combinations used to visualize NCC in CV nerve development.

(A and C) Embryos carrying Wnt1Cre;R26R (A) or Wnt1Cre;Z/EG (C) have all NCC and derivatives marked by expression of lacZ or GFP, respectively. Single arrowhead indicates second pharyngeal arch with all NCC labeled by Wnt1Cre-mediated recombination. (B and D) Within the cranial region, embryos carrying 6.5Pax3Cre;R26R (B) or 6.5Pax3Cre;Z/EG (D) preferentially label NCC emanating from R4 with β-galactosidase activity or GFP, respectively. The R4 NCC labeling is mosaic. Double arrowhead indicates second pharyngeal arch with mosaic labeling of R4 NCC. Hypaxial muscle progenitors are also labeled by this Cre driver (not shown). (A and B) Staining for β-galactosidase activity reveals NCC and derivatives labeled by Cre mediated recombination. Color image of β-galactosidase signal is overlain onto grayscale image of fluorescent DAPI signal to emphasize embryo morphology. (C-D) Double immunostain for GFP (green)and neuronal βIII tubulin (red) reveals NCC and neurons. DAPI labeling of all cell nuclei reveals pharyngeal arch morphology. Yellow box in (A) indicates approximate region of images shown in panels (C) and (D). Scale bar in (C) and (D) = 150μm.

In order to examine the contribution of NCC within the context of CV nerve formation we generated a transgenic Cre driver mouse line that, within the cranial region, preferentially marks NCC and derivatives relevant for development of the ear (Fig 1B). The new transgene, herein 6.5Pax3Cre, contains a ~6.5 kb region of genomic DNA 5’ of the Pax3 start. The region has been previously shown to contain within it two distinct enhancer elements, one driving expression in a subset of NCC (Milewski et al., 2004), and one driving expression in hypaxial muscle progenitors (Brown et al., 2005). Similar to the previously described transgenes, our new 6.5Pax3Cre transgene marks a subset of NCC and hypaxial muscle progenitors. Relevant for this study, the 6.5Pax3Cre transgene preferentially marks NCC emigrating from the R4 region that migrate into the second pharyngeal arch, but labels only rare cranial NCC cells from anterior or posterior axial positions in the head. Staining 6.5Pax3Cre;R26R embryos for β-galactosidase activity reveals mosaic labeling of NCC in the stream that fills the second pharyngeal arch (Fig. 1B). The pattern of mosaic NCC labeling within the second arch stream, and the absence of anterior and posterior cranial NCC, allows visualization of NCC contributing to development of the ear and CV nerve independently of other cranial NCC derivatives (Fig. 1D).

Second arch NCC stream envelops embryonic CV ganglion

In order to assess the spatial relationship between NCC and otic vesicle-derived neuroblasts of the developing CV ganglion, we examined whole mount Wnt1Cre:Z/EG embryos immunostained for GFP (identifying NCC) and ISL1 (Islet 1 transcription factor expressed in neurons, identifying neuronal cell bodies of the CV ganglion (Begbie et al., 2002; Ikeya et al., 1997)). We imaged immunostained embryos by confocal microscopy, collecting complete z-stacks of images through the region of interest. The z-stack images were examined as individual slices or were compiled and rendered to convey the 3D morphology of the developing CV ganglion.

We imaged embryos at E10.5 in the region of the otic vesicle, including the hindbrain at R4 and the proximal portion of the first and second pharyngeal arches (Fig. 2A). ISL1 staining of this region at E10.5 reveals the facial nerve ganglion and CV ganglion are nested directly anterior to the otic vesicle (Fig. 2B and C). The path of the R4 NCC stream appears to emerge from the neural tube, travels directly around the nested ganglia, and continues into the second pharyngeal arch (Fig 2B and C). In the region of the nested ganglia the spatial organization of the R4 NCC stream is tightly correlated with the ganglia with no significant NCC presence more than one or two cell diameters distant from the ganglia (Fig. 2B and C). Although nested, the facial ganglion and the CV ganglion are distinct (Fig 2C). Examination of an individual optical slices reveals that, for the CV ganglion, NCC are observed primarily on the exterior surface of the aggregated neuronal cell bodies (Fig. 2D). Rare NCC are present intercalated between neuronal cell bodies of the CV ganglion adjacent to areas of the otic vesicle that express low level of ISL1, indicative of regions of delaminating neuroblasts (Fig. 2D).

Figure 2. NCC stream co-localizes with nested facial and CV ganglia in E10.5 mouse embryos.

(A) Whole embryo stained with DAPI and imaged on fluorescent stereo microscope. Yellow box corresponds to region of imaged in (2B and 3A). (B) Wnt1Cre;Z/EG embryo double immunostained with GFP for NCC and ISL1 for neuronal cell bodies. DAPI stain indicates all cell nuclei. Nested facial and CV ganglia are visible anterior to the otic vesicle. Stream of NCC and derivatives emanates from R4, surrounds the nested ganglia, and fills the second pharyngeal arch. (C) NCC stream emanating from R4 envelopes nested facial and CV ganglion neurons as a sleeve. (D) Rare NCC are visible within the aggregated neuronal cell bodies of the CV ganglion, primarily near regions of the otic vesicle with low level ISL1 signal indicative of delaminating neuroblasts. Dotted lines in (C-D) indicate epithelium of otic vesicle. Arrowhead, region of otic vesicle of delaminating neuroblasts indicated by low level ISL1 signal; dotted lines, otic vesicle epithelium; CVG, cochleovestibular ganglion; FG, facial ganglion; HB, hindbrain; ovl, otic vesicle lumen; PA2, pharyngeal arch 2.

In order to gain understanding of the morphology of the developing CV ganglion, we utilized 3D image processing software Imaris to crop individual image slices to optically isolate the CV ganglion, the facial ganglion, and the otic vesicle, and to render fluorescence signal as a solid surface with shadows. Compilation of such images aids in visualizing the 3D organization of the ear and associated structures. Optical isolation and surface rendering of the CV ganglion, facial ganglion and otic vesicle of an E10.5 Wnt1Cre;Z/EG embryo immunostained for GFP (NCC) and ISL1 (neurons) allows the visualization of the two ganglia relative to the second arch NCC stream and the otic vesicle (Fig. 3 A,B). The CV ganglion appears as a saddle-shaped structure that “straddles” the anterior portion of the otic vesicle, with the facial ganglion nested within the anterior portion of the saddle. Two small processes project from the ventral edge of the CV ganglion extending medially and laterally over the anterior ventral region of the otic vesicle (Fig. 3 B-D’).

Figure 3. Early CV ganglion resembles a saddle straddling ventral otic vesicle.

Solid surface rendering of ganglion fluorescence signal and optical cropping of region of interest allows visualization of CV ganglion morphology of E10.5 embryo. ISL1 fluorescence (neuronal cell bodies) is rendered as solid surface to allow visualization of E10.5 mouse CV ganglion. (A) Otic region as indicated by yellow box in (Fig. 2A). Solid surface rendering of ISL1 signal indicates nested facial and CV ganglion straddle ventral otic vesicle at proximal region of second pharyngeal arch. Uncropped GFP immunostain of Wnt1Cre;Z/EG signal reveals NCC and derivatives filling the first and second pharyngeal arches. DAPI signal is cropped to define position of otic vesicle epithelium. (B) Lateral view of surface-rendered ganglion surfaces reveal two prongs extending across ventral otic vesicle. (C-C’) Ventral view of rendered ganglia cell bodies reveals nested organization of facial and CV ganglia and ventral prongs of CV ganglion that extend medially and laterally. (D-D’) Dorsal view of surface rendered ganglia reveals prongs of CV ganglion. Scale bars = 100μm with respect to individual image planes, CVG, CV ganglion; FG, facial ganglion; HB, hindbrain; lp, lateral projection; mp, medial projection; OV, otic vesicle; PA1, pharyngeal arch 1; PA2, pharyngeal arch 2.

Peripheral neurite extension of the CV ganglion

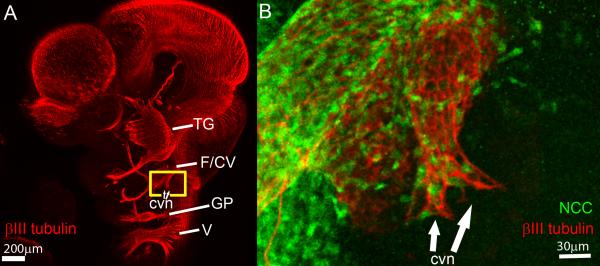

In order to understand the relationship between NCC and the centrally projecting axons and peripherally projecting neurites of the developing CV neurons, we performed whole mount immunostaining of Wnt1Cre;Z/EG and 6.5Pax3Cre;Z/EG embryos, staining for GFP (NCC) and βIII neuronal tubulin (neuronal projections). At E10.5, immunostaining for βIII neuronal tubulin reveals that peripheral projections of the CV nerve can be detected and the early fibers are organized as a lattice with longitudinal fibers and crossing fibers (Fig. 4 A-B). Immunostaining for GFP in Wnt1Cre:Z/EG embryos, in which all NCC express GFP, reveals that NCC are integrated throughout the entire CV nerve and are intercalated between the lattice-like neuronal projections (Fig. 4B). NCC are positioned within the junctions of the developing neuronal lattice and appear at the terminal extent of the projecting neurite branches with neuronal filopodia extending a short way beyond the most peripheral NCC cells.

Figure 4. CV Axons and neurites form a lattice with NCC intercalated in interstitial spaces at early stages of CV nerve development.

(A) Whole mount E10.5 mouse head stained with βIII neuronal tubulin to visualize central axons and peripheral neurites of cranial nerves. Yellow box indicates region imaged in panel B. (B) CV nerve of Wnt1Cre;Z/EG embryo immunostained for βIII neuronal tubulin (neurons) and GFP (NCC) indicates peripheral vestibular neurites are organized as a lattice with NCC intercalated between the spaces of the lattice and at distal-most extent of neurite projections . cvn, terminal peripheral neurites of CV nerve; F/CV, facial nerve/CV nerve; GP, glossopharyngeal nerve, TG, trigeminal nerve; V, vagal nerve.

By optically isolating the otic vesicle and developing CV nerve at sequential stages of embryogenesis it is possible to understand the 3D morphogenesis of the developing CV nerve (Fig 5. A-D). Immunostaining a Wnt1Cre:Z/EG embryo for GFP and βIII neuronal tubulin reveals that at E10.5 the peripheral neurites of the developing CV nerve project as two short branches, the future inferior vestibular nerve extending medially, and the future superior vestibular nerve extending laterally over the ventral anterior portion of the otic vesicle (Fig. 5A; supplementary material Movie 1). The two branches of peripheral neurite projections parallel the two projections of ganglion cell bodies observed with ISL1 staining (Fig. 3A-D’). Between the peripheral projecting fibers of the future inferior vestibular nerve and superior vestibular nerve, the future cochlear nerve is visible as a thicker blunt mass with few or no fine neurites projections at this stage (Fig. 5A).

Figure 5. Progression of CV nerve neurite outgrowth integrated with migratory NCC.

(A-D) Lateral view of CV nerve and otic vesicle morphology visualized in isolation by optical cropping of individual image planes in confocal image stacks. Whole embryos or isolated inner ears were immunostained for GFP to identify NCC, and with βIII tubulin to identify central axons and peripheral neurites. DAPI staining reveals all cell nuclei within optically cropped otic vesicle. (A) whole CV nerve and otic vesicle of E10.5 Wnt1CRE;Z/EG, (B) whole CV nerve and otic vesicle of E11.5 6.5Pax3Cre;ZEG, (C) whole CV nerve and developing inner ear of E12.5 6.5Pax3Cre;Z/EG, (D) developing cochlea and fan of neurites from early spiral nerve of E12.5 6.5Pax3Cre;Z/EG with accompanying population of NCC at region of extending peripheral neurites. (E) Schematic representation of E12.5 CV nerve and otic vesicle as in panel (C) to aid in visualization of 3D organization. (F) β-galactosidase staining of inner ear of neonatal 6.5Pax3Cre;R26R pup reveals NCC evenly distributed throughout the CV nerve. Scale bars = 100μm with respect to individual image planes. aa, anterior ampulla; aco, apical cochlea; ax, axonal projection to hindbrain; bco, basal cochlea; cn, cochlear nerve; cvg, cochleovestibular ganglion; dov, dorsal otic vesicle; hb, direction of hindbrain; ivn, inferior vestibular nerve; la, lateral ampulla; pa, posterior ampulla; pro, projecting cochlear neurites; sac, saccule; sg, spiral ganglion; svn, superior vestibular nerve; ut, utricle; vg, vestibular ganglia; vov, ventral otic vesicle.

Optical isolation of similarly labeled E11.5 6.5Pax3Cre:Z/EG embryos, in which there is mosaic expression of GFP in R4 NCC, reveals that the future inferior vestibular nerve elongates posteriorly medial to the otic vesicle between E10.5 and E11.5, while the future superior vestibular nerve extends dorso-laterally over the anterior otic vesicle, the superior and inferior vestibular nerves appearing to embrace the otic vesicle at the narrow region between the presumptive semi-circular canals and the future cochlea (Fig. 5 B). At this stage the future spiral ganglion has thickened, extending ventrally and slightly anterior with a few fine neurite projections as the first evidence of cochlear nerve fibers. Although the 6.5Pax3Cre:Z/EG marks only a mosaic subset of R4 NCC, GFP labeled NCC are observed in all regions of the developing CV nerve.

Optical isolation of otic tissues from 6.5Pax3Cre:Z/EG embryos at E12.5 reveals further morphogenesis of the CV nerve. At this stage the extending peripheral neurites of the early cochlear nerve are organized as a fan shape that projects ventrally, between the medially situated inferior vestibular nerve and laterally extending superior vestibular nerve (Fig. 5C and E, supplementary material Movie 2). Mosaic labeling of R4 NCC in the 6.5Pax3Cre:Z/EG embryos reveals NCC are present in all regions of the developing CV nerve and are densely associated with the terminal edge of the extending neurites of the developing cochlear nerve (Fig. 5 C-D). Fine neurite filopodia are visible beyond a dense wave front of NCC.

In order to visualize the distribution of NCC in the CV nerve at later stages of development we examined the inner ear of 6.5Pax3Cre;R26R at postnatal day 0 (P0) (Fig. 5F). In these samples β-galactosidase activity reveals that NCC are distributed throughout the extent of CV nerve, including all portions of the spiral ganglion and cochlear nerve, the inferior vestibular nerve, and the superior vestibular nerve. No staining is observed within the otic epithelium with this transgenic lineage reporter combination.

The temporal sequence of images presented here (Fig. 4B, Fig. 5A-F) reveal the morphogenesis of CV nerve neurons and associated NCC-derived glia in relation to the remodeling of the otic epithelium. We observe that peripheral neurite extension begins as early as E10.5. At that stage the fibers of the future inferior vestibular nerve, which will innervate the posterior crista ampulla, extend medially, while the future superior vestibular nerve, which will innervate the anterior and lateral cristae ampullae and the utricle, extends laterally. Each branch of fibers is associated with intercalated NCC. As development progresses, the inferior vestibular nerve fibers elongate posteriorly along the medial aspect of the otic vesicle as the superior vestibular nerve fibers extend dorso-laterally over the anterior aspect of the otic vesicle. As development progresses and the otic vesicle is remodeled into the membranous labyrinth, the two branches of nerve fibers encircle the otic vesicle at the junction between the presumptive vestibular structures and the future cochlea. The cochlear nerve, emerging between the vestibular nerve branches, begins to project peripheral neurites between E11.5 and E12.5, concomitant with the morphogenesis of the cochlea. Migratory NCC accompany projecting peripheral neurites at all stages and associate with all parts of the developed CV nerve.

NCC guide formation of the CV nerve

The visible association between NCC and CV neurons, and the demonstrated role of NCC in central axon guidance of the facial nerve, prompted us to examine directly whether formation of the CV nerve is likewise dependent on the presence of migratory NCC. To that end we examined chick embryos in which otic NCC were eliminated by physical ablation. Chick embryos in which the presumptive R4 region of the hindbrain was removed at HH stage 8 to 9+ (26-30 hours, 6-9 somites) were allowed to grow for 24 or 48 hours following ablation. The embryos were immunostained to identify NCC, (using HNK-1 antibody) and neurons (anti-βIII neuronal tubulin antibody) to assess the development of the CV nerve.

Confocal images of whole mount immunostained embryos reveal that the CV nerve of a developing chick embryo is similar to its analogous structure in mouse, being positioned anterior-ventral to the otic vesicle, but appearing somewhat more tightly unified with facial nerve than its mammalian counterpart (Fig. 6A-C). In HH17 stage chick embryos, the central axons of the combined CV nerve and facial nerve appears as a robust trunk extending from the combined ganglia medially to the hindbrain (Fig. 6B and C), consistent with previous analysis demonstrating central axon projection of the VIIIth nerve beginning at day 2.5 (Fritzsch et al., 1993). At the anterior otic vesicle the peripheral projection of the facial nerve bifurcates and extends ventrally from the CV nerve, which can be detected as short neurites contacting to the surface of the otic vesicle (Fig. 6B and C).

Figure 6. Elimination of NCC disrupts outgrowth of central axons.

Test of chick CV nerve development following ablation of R4 NCC. Neurons and NCC visualized by immunostain for βIII neuronal tubulin and HNK-1. (A-F) Normal HH stage 17 embryo with NCC intact not ablated. (A) Whole embryo visualized by DAPI labeling of all nuclei. Box indicates region imaged in other panels. (B) Otic region of normal non-ablated HH17 embryo stained for βIII tubulin and HNK-1 showing facial/CV nerves and otic vesicle. (C) Schematic representation of region imaged in panel (B) to aid in visualization of 3D organization. The CV nerve runs lateral-medial and slightly anterior-dorsal, connecting the laterally positioned otic vesicle with the medially positioned hindbrain at R4. (D-L) Similar views of CV nerve and otic vesicle as shown in (C) but optically cropped to eliminate facial nerve. (D-F) Non-ablated CV nerve of HH stage 17 control embryo. Trunk of central axons connects medial-anterior-dorsal to hindbrain co-localizing with NCC stream. (G-I) Otic region of embryo in which R4 NCC were ablated at HH stage 8 to 9+ followed by 24 h of incubation and growth to HH17. (G) NCC stream emanating from R4 is absent (hollow arrowhead). (H) Neuronal cells are present anterior to the otic vesicle as a rudimentary ganglion (gn), but lack central axons connecting to hindbrain (hollow arrowhead). (J-L) Following ablation of R4 NCC at HH stage 8 to 9+ and subsequent culture for 48hours to HH20 NCC regenerated from ectopic positions have migrated to otic region. In such embryos CV nerve forms central axons exactly matching pathway of regenerated ectopic NCC. (J) Rare NCC have migrated to the CV nerve from contralateral side (white asterisks), or from posterior region of the hindbrain (tailed arrows). (K) Central axons form (white asterisks and tailed arrows). (K) The central axons are co-localized with precisely along the migration pathways of regenerated ectopic NCC. Scale bars, 50 μm; hollow arrowhead, empty region normally occupied by migratory NCC from R4 and central axons from CV nerve; white asterisks, pathway of NCC regenerated from contralateral side; tailed arrows, pathway of NCC regenerated from region posterior to ablated section of hindbrain; A, anterior; ca, central axons; fn, facial nerve; gn, ganglion with no projections; hb, hindbrain; M, medial; OV otic vesicle; V, ventral.

Examining image planes through the CV nerve in non-ablated control embryos at HH17 reveals a sheath of NCC enveloping the CV neurons similar to that observed in mouse, consistent with recent similar studies (Freter et al., 2013). In non-ablated control embryos NCC surround the CV nerve forming a corridor from the anterior otic vesicle to the hindbrain (Fig 6D-F). In contrast, in embryos where R4 NCC had been removed at HH stage 8 to 9+ followed by 24 hours of growth to HH17 results in absence of the NCC corridor between the CV ganglion and the hindbrain (Fig. 6 G,I). When NCC are eliminated in this manner CV neurons are observed as an isolated ganglion without central extensions to the hindbrain (Fig. 6H and I).

Owing to developmental plasticity of NCC, ablation of R4 at HH stage 8 to 9+ and subsequent growth for 48 hours often resulted in regeneration of NCC from anterior or posterior axial levels (Fig. 6J-L). Where such regeneration occurred CV nerve axons formed exactly and exclusively along the regenerated NCC migration pathways (Fig. 6J-L). Even when the regenerated NCC were very few in number, central CV nerve axon projections form, localized precisely within the path traversed by the regenerated NCC. In these cases the CV nerve axon destination corresponded to ectopic anterior or posterior positions, or from the contralateral side of the neural tube, from which the regenerated NCC arose. The ectopic axon pathways corresponding to the regenerated NCC pathway provides further evidence that development of the CV nerve is dependent on interactions with migratory NCC from the hindbrain.

Discussion

Development of CV neurons and associated NCC

This report describes our analysis of the 3D morphological development of the CV nerve with respect to neuronal progenitors and glial progenitors, derived, respectively, from the otic vesicle and NCC. In terms of morphology, our observations of mammalian CV nerve formation are largely consistent with previous descriptions of developing CV nerve shape (Kopecky et al., 2012; Streeter, 1906; Yang et al., 2011), with added insights revealed by the use of molecular markers and lineage trace reporters. Notably, we find that neuronal progenitors and glial progenitors interact extensively at all stages of nerve development.

We detect central axon and peripheral neurite extensions slightly earlier than has been reported by dye labeling studies, observing peripheral neurites across the ventral-anterior otic vesicle as early as E10.5. The initial peripheral neurites extend as two branches of fibers, the future inferior vestibular nerve projecting medially, and the future superior vestibular nerve projecting laterally. The future cochlear nerve begins to extend peripheral neurites at E11.5, a day later than the vestibular nerves. As development progresses the peripheral neurites of the cochlear nerve form a fan that spreads open concomitant with the extension of the cochlea.

Using the Wnt1-Cre and 6.5Pax3Cre drivers to lineage label NCC we observe that the NCC stream originating from R4 covers the nested facial and CV ganglia as a close-fitting sleeve and extends into the second pharyngeal arch. Association of NCC with the developing CV ganglion has been described previously by 2D section analysis (Breuskin et al., 2010; Davies, 2007), but the 3D rendering of multiple 2D image planes presented here allows the sleeve-like association of the R4 NCC stream to be appreciated much more clearly.

The association of NCC as a sheath surrounding the combined facial and CV ganglia is consistent with results of a similar recent study of chick and mice demonstrating that migratory NCC form corridors within which cranial sensory neurons migrate (Freter et al., 2013). In that study the NCC corridors surrounding the neuron progenitors of the combined facial and CV ganglia were demonstrated to be important for facilitating migration of the neuroblasts and for accurate growth of central axons to the hindbrain. Our observations reported here indicate that, in addition to forming a sleeve surrounding CV neuronal cell bodies and central axons, NCC interact intimately with peripheral projections of developing neurons. We also observe the early central and peripheral projections are organized a lattice with NCC intercalated between the rungs of the lattice and at the terminal edges of extending neurites. As the CV nerve grows and develops, NCC continue their intimate localization with all parts of the nerve, migrating as a wave front in association with extending peripheral neurites.

The early and extensive association of NCC with CV neurons indicates that CV nerve development should be considered as a coordinated event between neuronal and glial progenitors. That development of cranial nerves requires coordination between neuronal progenitors and NCC is supported by observations of nerve abnormalities resulting from disruptions of NCC migration or disruptions of signaling between NCC and neurons. Specifically, loss of Neuropilin-Semaphorin signaling results in abnormal migration of cranial NCC, and causes corresponding abnormal migration and positioning of cranial sensory neurons and nerve fibers (Schwarz et al., 2008). Similarly, disrupting signaling between neuronal and glial progenitors also interferes with development of cranial nerves including the CV nerve. ERBB2, a receptor that mediates neuron-glia interactions via the ligand Neuregulin 1 (reviewed in (Corfas et al., 2004)) is required for proper development of the CV nerve. Loss of ErbB2 results in altered migration of CV neuronal cell bodies, abnormal targeting of CV peripheral neurites and reduced number of CV neurons (Morris et al., 2006). While these phenotypes indicate that NCC-derived glial progenitors influence guidance of peripheral neurites, there are clearly other tissues and signaling interactions that are also critical for formation of inner ear neuron migration and growth and targeting of central axons and peripheral neurites. For example, signaling by neurotrophins, which are expressed in the sensory epithelia are also important for survival and guidance of cochlear and vestibular peripheral neurites (Tessarollo et al., 2004).

The close association of NCC with CV neuroblasts is relevant for interpreting previous studies of CV nerve formation and axon guidance. Much of our knowledge of CV nerve axon guidance is built on in vitro culture of chick CV ganglia (Ard et al., 1985; Bianchi and Cohan, 1991; Hemond and Morest, 1992). Based on the close association of NCC with the developing ganglia observed here, it is clear that in vitro explants of isolated CV ganglia would contain numerous associated NCC.

In addition to interactions between NCC and neurons in development of the CV nerve, the proximity of the R4 NCC stream to the otic vesicle may be important for axial patterning of the inner ear. Inner ear patterning has been elucidated in large part by amphibian or chick experiments involving rotational transplants of otic placode, otic vesicle or hindbrain (Bok et al., 2005; Harrison, 1936; Wu et al., 1998). Rotational transplants of chick otic cup tissue at stages HH 10-12 (11 somites – 16 somites) indicate that the anterior-posterior axis of the developing otic tissue is dictated by the host environment at that stage, and that the host influence is not mediated by the neural tube (Bok et al., 2005). Because the R4 NCC stream would be present at this stage, having emerged from the neural tube from HH stage 9 through 11 (7 somites – 13 somites)(Tosney, 1982), the presence of host NCC could account for the anterior-posterior patterning influence on the transplanted tissue. A possible role for R4 NCC in patterning the inner ear is also supported by genetic evidence. Hoxa2 is known to be important for anterior posterior patterning for both the hindbrain and second arch NCC (Gendron-Maguire et al., 1993; Rijli et al., 1993). Mutation of HOXA2 in humans can impact development of the inner ear (Alasti et al., 2008), but, again, the effect is unlikely to be mediated by the hindbrain (Bok et al., 2005). Because mutation of Hoxa2 causes significant mis-patterning of R4 NCC it is possible that abnormal anterior-posterior specification of the NCC could be responsible for human HOXA2 inner ear defects.

Analysis of Wnt1-Cre and 6.5Pax3Cre drivers in combination with R26R and Z/EG reporters does not indicate any significant NCC contribution to the neuronal population of the CV nerve nor to the otic epithelium, a result consistent with many previous studies (Breuskin et al., 2010; D'Amico-Martel and Noden, 1983; van Campenhout, 1935) but dissimilar from a recent report of transgenic mouse lineage trace analysis (Freyer et al., 2011).

Early central axon and peripheral neurite extension integrated with NCC

For CV nerve development, the timing of projection of central axons to the hindbrain and peripheral neurites to the sensory targets in the otic epithelium has been previously examined by neuronal dye tracing. With that method central axons are detected as early as embryonic day 12.5 (E12.5) and peripheral neurites at E11.5 (Fritzsch, 2003; Matei et al., 2005). Radiolabeling of terminal mitoses has also been used to investigate the temporal profile of CV nerve development. Terminal mitoses staging indicates that CV Schwann cells reach maturity much later during embryogenesis than the corresponding neuronal cells with which they associate (Altman and Bayer, 1982; Ruben, 1967).

The results of the present study, based on immunostaining for βIII neuronal tubulin, demonstrate that central axon projection and peripheral neurite extension can be detected beginning as early as E10.5, somewhat earlier than reported based on dye labeling analysis. Moreover, immunostaining NCC lineage reporters in conjunction with immunolabeling of neuronal projections indicates that, although the neuronal and glial cell populations may reach their terminal mitosis at different development stages, they are coordinately involved in the initial morphological development of the nerve. Additionally, the resolution of the confocal 3D reconstruction images reveals the early central axonal trunk and peripheral neurite branches of the E10.5 CV nerve are organized as a lattice structure with NCC arranged between the interconnecting rungs of the neurite lattice. NCC are also positioned at junctions near terminal extending filopodia. The position of NCC at junctions of neurite filopodia is reminiscent of historical observations of Schwann cells at junctions of branching peripheral neurites in developing frog embryos (Harrison, 1924). These observations that NCC are present throughout the lattice of early CV nerve reinforces the idea that neuronal and glial components of CV nerve architecture are established concomitantly at early stages of nerve development.

From the images presented here it is unclear whether NCC precede or follow the peripheral neurite projections. The recent analysis of epibranchial placode neuron development by Freter, et. al. may provide some clue regarding this issue (Freter et al., 2013). In that study of facial ganglion development, formation of the ganglion and growth of central axons was demonstrated to depend upon reciprocal interactions between NCC and epibranchial placode neurons. Additionally, in vitro cultured placodal neurons were shown to extend processes better on a substrate of NCC than on a substrate of mesoderm. While the analysis did not distinguish between central axons and peripheral neurites, the result suggests that NCC facilitate formation of axon and neurite projections by providing a favorable substrate for outgrowth.

Peripheral neurite extension of cochlear nerve accompanied by a wave of NCC

One of the most striking observations from this analysis is that the early peripheral neurites of the cochlear nerve project fan-like with NCC represented robustly at the wave front of terminal neurite extensions. The shape of the early cochlear nerve as a fan opening with the growth of the cochlea is consistent with the known maturation pattern of spiral ganglion neurons, wherein neurons at the base of the cochlea mature to their final cell division before those at the apex (Koundakjian et al., 2007; Matei et al., 2005; Ruben, 1967). Importantly, the presence of migratory NCC in association with spiral ganglion neurons suggests that NCC may play a role in guidance or growth of the peripheral neuronal projections in a manner similar to their role in facilitating growth and targeting of central axons (Begbie and Graham, 2001; Freter et al., 2013).

The issue of whether NCC guide peripheral nerve outgrowth has been examined previously with mixed results. Yntema demonstrated that NCC are required for migration of peripheral motor nerve fibers into the fore- and hind-limb of Amblystoma (Yntema, 1943a). He also observed that ablation of cranial NCC caused changes in the course of the trigeminal and facial nerves in chick (Yntema, 1944). Consistent with the notion that NCC and peripheral nerve outgrowth are linked Noakes et. al. observed that Schwann cells migrate ahead of neuronal peripheral neurites in the forelimb in chick (Noakes and Bennett, 1987), and that ablation of NCC blocked extension of motor neurons into the limb (Noakes et al., 1988).

Analysis of mice with mutations of ErbB2 or ErbB3, in which migration and survival of Schwann cell progenitors are impaired, provides further evidence that Schwann cells progenitors play and important role in growth and formation of cranial sensory and motor nerves (Erickson et al., 1997; Lee et al., 1995). For the cochlear nerve, loss of ErbB2 results in abnormal migration of spiral ganglion neurons and aberrant projections of afferent peripheral neurites (Morris et al., 2006). Central axon projections are targeted correctly. Thus, migration of NCC glial progenitors may not be important for central axon guidance. Alternatively, the normal central axon guidance may be integrated with early NCC migration not disrupted by loss of ErbB2, which impairs Schwann cell survival at later stages.

Contradicting the model that NCC play a role in axon guidance of peripheral nerves, genetic evidence from mice indicates that NCC are dispensable for the process. Genetic ablation of NCC using Wnt1Cre to activate a Diphtheria toxin allele results in disorganized growth of nerves including the facial nerve, but the corda tympani and greater superficial petrosal components of the facial nerve form relatively normally (Coppola et al., 2010). The prevailing view that Schwann cell progenitors do not guide peripheral neurite outgrowth (Woodhoo and Sommer, 2008), is based in part on observations ofPax3splotch mutant mice, which lack Schwann cells in nerves of the sacral region but have correctly targeted hindlimb motor nerves (Grim et al., 1992). The disparate evidence regarding the role of NCC-derived glia in guiding peripheral neurite outgrowth may reflect variation in guidance mechanisms between specific nerves types, difference in axial levels, or may reflect variation between organisms. Alternatively, differences may result from variation in method of NCC perturbation with respect to the number of surviving or regenerating NCC.

Elimination of NCC disrupts outgrowth and targeting of central axons and peripheral neurites of the CV nerve

Owing to the close association of NCC with the developing CV neuronal cells in mice we assessed the effect of NCC ablation on axon outgrowth of the CV nerve in chick. Severe disruption of central axon and peripheral neurite outgrowth occurred following ablation of R4 NCC. The results recapitulate those reported for the facial nerve (Begbie and Graham, 2001; Freter et al., 2013), and demonstrate that axon growth for the CV nerve is likewise integrated with the stream of migratory NCC from R4.

Owing to the plasticity of NCC, physical ablation often resulted in migration of NCC regenerated from ectopic positions. In such cases, growth of axons was guided precisely along the pathways or corridors defined by the regenerating ectopic NCC. Similar results have been observed for neurons of the geniculate ganglion following genetic ablation of R4 NCC in mice (Chen et al., 2011). Importantly, we observe that CV nerve axons project and are guided to ectopic positions of the central nervous system when very few, or even isolated individual NCC are present. In all cases, CV axonal and neurite processes follow with perfect concordance the pathways of migratory NCC. The observation that isolated regenerating NCC are sufficient to guide central axon growth suggests that experimental paradigms wherein even a few isolated NCC are present may not definitively test the role of NCC derived glia in axon/neurite outgrowth and guidance.

Conclusions

The otic vesicle-derived neurons and NCC-derived glial populations of the CV nerve develop in tandem from early stages of CV nerve morphogenesis. NCC emerging from R4 are arranged as a sleeve that surrounds the nested CV and facial ganglia and the axons projecting centrally from them. Early peripheral neurite projections are organized as a lattice structure with NCC glial progenitors intercalated throughout. As CV nerve morphogenesis progresses, NCC continue to be robustly associated with peripherally projecting neurites of the vestibular and cochlear nerves. Perturbation of R4 NCC impairs formation of CV central axon projections, with central axons forming precisely along aberrant migration pathways of ectopically regenerating NCC. Together these results support a model wherein the CV nerve, as well as other cranial sensory nerves, develops by integrated interactions between placodally-derived neuronal progenitors and NCC-derived glial progenitors.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

Grant Support: Research in the Sandell laboratory is supported by the University of Louisville and by P20 RR017702 to Dr. Robert M. Greene, Birth Defects Center, University of Louisville, Louisville, KY. Research in the Trainor laboratory is supported by the Stowers Institute for Medical Research and the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (R01 DE 016082). The Microscopy Suite at the Cardiovascular Innovation Institute in Louisville, KY is supported by GM103507.

Abbreviations

- 3D

3-dimensional

- CV

cochleovestibular

- E

embryonic day

- GFP

Green Fluorescent Protein

- NCC

neural crest cells

- P

postnatal day

- R

rhombomere

References

- Alasti F, Sadeghi A, Sanati MH, Farhadi M, Stollar E, Somers T, Van Camp G. A Mutation in HOXA2 Is Responsible for Autosomal-Recessive Microtia in an Iranian Family. The American Journal of Human Genetics. 2008;82:982–991. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altman J, Bayer S. Development of the cranial nerve ganglia and related nuclei in the rat. Springer-Verlag; Berlin: 1982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appler JM, Goodrich LV. Connecting the ear to the brain: Molecular mechanisms of auditory circuit assembly. Progress in Neurobiology. 2011;93:488–508. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2011.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ard MD, Morest DK, Hauger SH. Trophic interactions between the cochleovestibular ganglion of the chick embryo and its synaptic targets in culture. Neuroscience. 1985;16:151–170. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(85)90053-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begbie J, Ballivet M, Graham A. Early Steps in the Production of Sensory Neurons by the Neurogenic Placodes. Molecular and Cellular Neuroscience. 2002;21:502–511. doi: 10.1006/mcne.2002.1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begbie J, Brunet JF, Rubenstein JL, Graham A. Induction of the epibranchial placodes. Development. 1999;126:895–902. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.5.895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begbie J, Graham A. Integration between the epibranchial placodes and the hindbrain. Science. 2001;294:595–598. doi: 10.1126/science.1062028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi LM, Cohan CS. Developmental regulation of a neurite-promoting factor influencing statoacoustic neurons. Developmental Brain Research. 1991;64:167–174. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(91)90221-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bok J, Bronner-Fraser M, Wu DK. Role of the hindbrain in dorsoventral but not anteroposterior axial specification of the inner ear. Development. 2005;132:2115–2124. doi: 10.1242/dev.01796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bok J, Chang W, Wu DK. Patterning and morphogenesis of the vertebrate inner ear. International journal of developmental biology. 2007;51:521. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.072381jb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breuskin I, Bodson M, Thelen N, Thiry M, Borgs L, Nguyen L, Stolt C, Wegner M, Lefebvre PP, Malgrange B. Glial but not neuronal development in the cochleo-vestibular ganglion requires Sox10. Journal of neurochemistry. 2010;114:1827–1839. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06897.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown CB, Engleka KA, Wenning J, Min Lu M, Epstein JA. Identification of a hypaxial somite enhancer element regulating Pax3 expression in migrating myoblasts and characterization of hypaxial muscle Cre transgenic mice. Genesis. 2005;41:202–209. doi: 10.1002/gene.20116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carney PR, Silver J. Studies on cell migration and axon guidance in the developing distal auditory system of the mouse. The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1983;215:359–369. doi: 10.1002/cne.902150402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chai Y, Jiang X, Ito Y, Bringas P, Jr., Han J, Rowitch DH, Soriano P, McMahon AP, Sucov HM. Fate of the mammalian cranial neural crest during tooth and mandibular morphogenesis. Development. 2000;127:1671–1679. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.8.1671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Streit A. Induction of the inner ear: Stepwise specification of otic fate from multipotent progenitors. Hearing Research. 2013;297:3–12. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2012.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Takano-Maruyama M, Gaufo GO. Plasticity of neural crest–placode interaction in the developing visceral nervous system. Developmental dynamics. 2011;240:1880–1888. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coppola E, Rallu M, Richard J, Dufour S, Riethmacher D, Guillemot F, Goridis C, Brunet J-F. Epibranchial ganglia orchestrate the development of the cranial neurogenic crest. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2010;107:2066–2071. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910213107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corfas G, Velardez MO, Ko C-P, Ratner N, Peles E. Mechanisms and Roles of Axon-Schwann Cell Interactions. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2004;24:9250–9260. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3649-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Culbertson MD, Lewis ZR, Nechiporuk AV. Chondrogenic and Gliogenic Subpopulations of Neural Crest Play Distinct Roles during the Assembly of Epibranchial Ganglia. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e24443. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Amico-Martel A, Noden D. Contributions of placodal and neural crest cells to avian cranial peripheral ganglia. Am. J. Anat. 1983;166:445–468. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001660406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies D. Temporal and spatial regulation of α6 integrin expression during the development of the cochlear-vestibular ganglion. The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 2007;502:673–682. doi: 10.1002/cne.21302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Echelard Y, Vassileva G, McMahon AP. Cis-acting regulatory sequences governing Wnt-1 expression in the developing mouse CNS. Development. 1994;120:2213–2224. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.8.2213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erickson SL, O'Shea KS, Ghaboosi N, Loverro L, Frantz G, Bauer M, Lu LH, Moore MW. ErbB3 is required for normal cerebellar and cardiac development: a comparison with ErbB2-and heregulin-deficient mice. Development. 1997;124:4999–5011. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.24.4999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fekete DM, Campero AM. Axon guidance in the inner ear. International journal of developmental biology. 2007;51:549–556. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.072341df. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freter S, Fleenor SJ, Freter R, Liu KJ, Begbie J. Cranial neural crest cells form corridors prefiguring sensory neuroblast migration. Development. 2013;140:3595–3600. doi: 10.1242/dev.091033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freyer L, Aggarwal V, Morrow BE. Dual embryonic origin of the mammalian otic vesicle forming the inner ear. Development. 2011;138:5403–5414. doi: 10.1242/dev.069849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritzsch B. Development of inner ear afferent connections: forming primary neurons and connecting them to the developing sensory epithelia. Brain research bulletin. 2003;60:423–433. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(03)00048-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritzsch B, Christensen MA, Nichols DH. Fiber pathways and positional changes in efferent perikarya of 2.5-to 7-day chick embryos as revealed with dil and dextran amiens. Journal of neurobiology. 1993;24:1481–1499. doi: 10.1002/neu.480241104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gendron-Maguire M, Mallo M, Zhang M, Gridley T. Hoxa-2 mutant mice exhibit homeotic transformation of skeletal elements derived from cranial neural crest. Cell. 1993;75:1317–1331. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90619-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grim M, Halata Z, Franz T. Schwann cells are not required for guidance of motor nerves in the hindlimb in Splotch mutant mouse embryos. Anat Embryol. 1992;186:311–318. doi: 10.1007/BF00185979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groves AK, Fekete DM. Shaping sound in space: the regulation of inner ear patterning. Development. 2012;139:245–257. doi: 10.1242/dev.067074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanani M. Satellite glial cells in sensory ganglia: from form to function. Brain Research Reviews. 2005;48:457–476. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2004.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison RG. Neuroblast versus sheath cell in the development of peripheral nerves. The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1924;37:123–205. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison RG. Relations of Symmetry in the Developing Ear of Amblystoma Punctatum. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1936;22:238–247. doi: 10.1073/pnas.22.4.238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemond SG, Morest DK. Tropic effects of otic epithelium on cochleo-vestibular ganglion fiber growth in vitro. The Anatomical record. 1992;232:273–284. doi: 10.1002/ar.1092320212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeya M, Lee SMK, Johnson JE, McMahon AP, Takada S. Wnt signalling required for expansion of neural crest and CNS progenitors. Nature. 1997;389:966–970. doi: 10.1038/40146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopecky B, Johnson S, Schmitz H, Santi P, Fritzsch B. Scanning thin-sheet laser imaging microscopy elucidates details on mouse ear development. Developmental dynamics. 2012 doi: 10.1002/dvdy.23736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koundakjian EJ, Appler JL, Goodrich LV. Auditory Neurons Make Stereotyped Wiring Decisions before Maturation of Their Targets. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2007;27:14078–14088. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3765-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladher RK, O'Neill P, Begbie J. From shared lineage to distinct functions: the development of the inner ear and epibranchial placodes. Development. 2010;137:1777–1785. doi: 10.1242/dev.040055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K-F, Simon H, Chen H, Bates B, Hung M-C, Hauser C. Requirement for neuregulin receptor erbB2 in neural and cardiac development. Nature. 1995;378:394–398. doi: 10.1038/378394a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matei V, Pauley S, Kaing S, Rowitch D, Beisel KW, Morris K, Feng F, Jones K, Lee J, Fritzsch B. Smaller inner ear sensory epithelia in Neurog1 null mice are related to earlier hair cell cycle exit. Developmental dynamics. 2005;234:633–650. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milewski RC, Chi NC, Li J, Brown C, Lu MM, Epstein JA. Identification of minimal enhancer elements sufficient for Pax3 expression in neural crest and implication of Tead2 as a regulator of Pax3. Development. 2004;131:829–837. doi: 10.1242/dev.00975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris JK, Maklad A, Hansen LA, Feng F, Sorensen C, Lee K-F, Macklin WB, Fritzsch B. A disorganized innervation of the inner ear persists in the absence of ErbB2. Brain research. 2006;1091:186–199. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.02.090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noakes PG, Bennett MR. Growth of axons into developing muscles of the chick forelimb is preceded by cells that stain with Schwann cell antibodies. The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1987;259:330–347. doi: 10.1002/cne.902590303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noakes PG, Bennett MR, Stratford J. Migration of schwann cells and axons into developing chick forelimb muscles following removal of either the neural tube or the neural crest. The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1988;277:214–233. doi: 10.1002/cne.902770205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novak A, Guo C, Yang W, Nagy A, Lobe CG. Z/EG, a double reporter mouse line that expresses enhanced green fluorescent protein upon cre-mediated excision. Genesis. 2000;28:147–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborne NJ, Begbie J, Chilton JK, Schmidt H, Eickholt BJ. Semaphorin/neuropilin signaling influences the positioning of migratory neural crest cells within the hindbrain region of the chick. Developmental dynamics. 2005;232:939–949. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rijli FM, Mark M, Lakkaraju S, Dierich A, Dolle P, Chambon P. A homeotic transformation is generated in the rostral branchial region of the head by disruption of Hoxa-2, which acts as a selector gene. Cell. 1993;75:1333–1349. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90620-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbluth J. The fine structure of acoustic ganglia in the rat. The Journal of cell biology. 1962;12:329–359. doi: 10.1083/jcb.12.2.329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruben RJ. Development of the inner ear of the mouse: a radioautographic study of terminal mitoses. Acta Oto-Laryngologica. 1967;220(Suppl):221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandell LL, Kurosaka H, Trainor PA. Whole mount nuclear fluorescent imaging: Convenient documentation of embryo morphology. Genesis. 2012;50:844–850. doi: 10.1002/dvg.22344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlosser G. Chapter Four - Making Senses: Development of Vertebrate Cranial Placodes. In: Kwang J, editor. International Review of Cell and Molecular Biology. San Diego. Academic Press; 2010. pp. 129–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz Q, Vieira JM, Howard B, Eickholt BJ, Ruhrberg C. Neuropilin 1 and 2 control cranial gangliogenesis and axon guidance through neural crest cells. Development. 2008;135:1605–1613. doi: 10.1242/dev.015412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soriano P. Generalized lacZ expression with the ROSA26 Cre reporter strain. Nat Genet. 1999;21:70–71. doi: 10.1038/5007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streeter GL. On the development of the membranous labyrinth and the acoustic and facial nerves in the human embryo. American Journal of Anatomy. 1906;6:139–165. [Google Scholar]

- Tessarollo L, Coppola V, Fritzsch B. NT-3 Replacement with Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor Redirects Vestibular Nerve Fibers to the Cochlea. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2004;24:2575–2584. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5514-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tosney K. The segregation and early migration of cranial neural crest cells in the avian embryo. Developmental biology. 1982;89:13–24. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(82)90289-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Campenhout E. Experimental researches on the origin of the acoustic ganglion in amphibian embryos. Journal of Experimental Zoology. 1935;72:175–193. [Google Scholar]

- Woodhoo A, Sommer L. Development of the Schwann cell lineage: From the neural crest to the myelinated nerve. Glia. 2008;56:1481–1490. doi: 10.1002/glia.20723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu DK, Nunes FD, Choo D. Axial specification for sensory organs versus non-sensory structures of the chicken inner ear. Development. 1998;125:11–20. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.1.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang T, Kersigo J, Jahan I, Pan N, Fritzsch B. The molecular basis of making spiral ganglion neurons and connecting them to hair cells of the organ of Corti. Hearing Research. 2011;278:21–33. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2011.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yntema CL. Deficient efferent innervation of the extremities following removal of neural crest in Amblystoma. Journal of Experimental Zoology. 1943a;94:319–349. [Google Scholar]

- Yntema CL. An experimental study on the origin of the sensory neurones and sheath cells of the IXth and Xth cranial nerves in Amblystoma punctatum. Journal of Experimental Zoology. 1943b;92:93–119. [Google Scholar]

- Yntema CL. Experiments on the origin of the sensory ganglia of the facial nerve in the chick. The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1944;81:147–167. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.