Abstract

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection of hepatocytes leads to transcriptional induction of the chemokine CXCL10, which is considered an interferon (IFN)-stimulated gene. However, we have recently shown that IFNs are not required for CXCL10 induction in hepatocytes during acute HCV infection. Since the CXCL10 promoter contains binding sites for several proinflammatory transcription factors, we investigated the contribution of these factors to CXCL10 transcriptional induction during HCV infection in vitro. Wild-type and mutant CXCL10 promoter-luciferase reporter constructs were used to identify critical sites of transcriptional regulation. The proximal IFN-stimulated response element (ISRE) and NF-κB binding sites positively regulated CXCL10 transcription during HCV infection as well as following exposure to poly(I·C) (a Toll-like receptor 3 [TLR3] stimulus) and 5′ poly(U) HCV RNA (a retinoic acid-inducible gene I [RIG-I] stimulus) from two viral genotypes. Conversely, binding sites for AP-1 and CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein β (C/EBP-β) negatively regulated CXCL10 induction in response to TLR3 and RIG-I stimuli, while only C/EBP-β negatively regulated CXCL10 during HCV infection. We also demonstrated that interferon-regulatory factor 3 (IRF3) is transiently recruited to the proximal ISRE during HCV infection and localizes to the nucleus in HCV-infected primary human hepatocytes. Furthermore, IRF3 activated the CXCL10 promoter independently of type I or type III IFN signaling. The data indicate that sensing of HCV infection by RIG-I and TLR3 leads to direct recruitment of NF-κB and IRF3 to the CXCL10 promoter. Our study expands upon current knowledge regarding the mechanisms of CXCL10 induction in hepatocytes and lays the foundation for additional mechanistic studies that further elucidate the combinatorial and synergistic aspects of immune signaling pathways.

INTRODUCTION

Recognition of viral components by pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) during hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection leads to the induction of various proinflammatory and antiviral genes, including interferons (IFNs), cytokines, and chemokines (1–5). The profile of induced genes depends upon the transcription factors that are active within the nucleus (1, 6–8). However, there is considerable redundancy within the PRR signaling network that leads to transcription factor activation (1, 8–10). For example, signaling from either Toll-like receptor 3 (TLR3) or retinoic acid-inducible gene I (RIG-I) following exposure to double-stranded viral RNAs activates an overlapping set of transcription factors that includes nuclear factor (NF)-κB and interferon-regulatory factors (IRFs) (11). Both of these PRRs also activate mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase signaling pathways, which in turn regulate activator protein 1 (AP-1) and CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein β (C/EBP-β) activity (12–16). Putative binding sites for all of these transcription factors have been annotated in the promoter for the proinflammatory chemokine CXCL10 (17), which recruits natural killer (NK) cells, CD4+ T cells, and CD8+ T cells to the HCV-infected liver (18, 19) and is associated with the failure of IFN-based antiviral therapy (20–22).

NF-κB is considered a central positive regulator of the inflammatory response, and its role in the induction of genes such as those for tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), interleukin-8 (IL-8), and IL-1β has been well characterized (23, 24). Prior to activation, NF-κB heterodimers are held in a dormant state within the cytoplasm by the IκB family of repressor proteins (24, 25). Virus-induced PRR signaling leads to phosphorylation and ubiquitin-mediated proteasomal degradation of these repressor proteins, allowing activated NF-κB to translocate into the nucleus and bind to the promoters of proinflammatory genes, such as CXCL10 (26).

Recently, Li et al. showed that HCV infection of TLR3-expressing hepatoma cells can induce NF-κB binding to the CXCL10 promoter (4). While this study indicates that NF-κB is a critical regulator of CXCL10 induction during early HCV infection, the other proinflammatory transcription factor binding sites annotated in the CXCL10 promoter (noted above) could provide additional levels of transcriptional regulation. One likely contributor is the dimeric transcription factor AP-1, which consists of members of the Fos, Jun, ATF, and JDP families of proteins (27, 28). AP-1 is involved in the regulation of a wide variety of genes, and its regulatory function can vary, depending on which subunits comprise the dimer and the surrounding cellular environment (28–30). Dynamic functionality is also observed with the transcription factor C/EBP-β, which can form a homodimer or a heterodimer with other C/EBP proteins to induce a wide variety of gene products, including proinflammatory cytokines (31–34). Both AP-1 and C/EBP-β have also been shown to activate transcription of CXCL8 (i.e., IL-8) (35, 36). This chemokine possesses many structural and functional similarities to CXCL10, and its levels are also elevated in patients with chronic hepatitis C (37–40). Thus, AP-1 and C/EBP-β may contribute to the proinflammatory induction of CXCL10 during HCV infection in a manner similar to that for NF-κB.

IRFs are also recruited to chemokine promoters during virus infection. For example, IRF1 and IRF3 bind the CXCL8 promoter during respiratory syncytial virus and HCV infection, respectively (23, 41). Similarly, the CXCL10 promoter is bound by IRF1 during rhinovirus infection and by IRF1, IRF3, and IRF7 during influenza A virus infection (42, 43). Activation of IRF3 and IRF7 can also lead to the induction of antiviral type I IFNs (alpha IFN [IFN-α] and IFN-β) and type III IFNs (IL-28A, IL-28B, and IL-29) in hepatocytes (1–6). These secreted cytokines can act in a paracrine manner to amplify chemokine and cytokine responses in adjacent liver cells through activation of Janus kinases (JAKs)/signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) signaling and the formation of the IFN-stimulated gene factor 3 (ISGF3) complex (1, 6–8). The type II IFN (IFN-γ) produced by NK cells, CD8+ Tc cells, and CD4+ TH1 cells can also induce STAT signaling (1, 8, 9). As the CXCL10 promoter contains both putative ISREs and putative STAT-binding sites, it responds to all 3 types of IFN and is considered an ISG (11, 17). However, neutralization of type I and type III IFNs was previously shown to have no effect on CXCL10 production in primary human hepatocytes and hepatoma cells expressing functional TLR3 and RIG-I during early HCV infection (44). It has yet to be determined if IRFs play a role in CXCL10 induction independently of the action of type I and type III IFNs.

In order to better understand how CXCL10 is regulated in hepatocytes during HCV infection, the current study characterized the contribution of proinflammatory and antiviral transcription factors in CXCL10 induction. Our data demonstrate that NF-κB and IRF3 are crucial positive regulators of CXCL10 induction both during acute HCV infection and following treatment with TLR3- and RIG-I-specific pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs). In contrast, AP-1 and C/EBP-β appear to be minor negative regulators of CXCL10 induction during PAMP treatment and have a limited impact during acute HCV infection. Our data also show that IRF3 localizes to the nucleus during HCV infection of primary human hepatocytes (PHHs) and is recruited to the CXCL10 promoter during HCV infection of immortalized hepatoma cells. Neither type I nor type III IFNs are required for IRF3-mediated induction of CXCL10 promoter activity. These results indicate that multiple factors control CXCL10 induction in hepatocytes during HCV infection and that these factors induce CXCL10 transcription independently of IFN signaling.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells.

PH5CH8 immortalized hepatocytes (45) and Huh7 hepatoma cells stably transduced with a FLAG-TLR3-encoding lentiviral vector (TLR3-positive [TLR3+]/RIG-I-positive [RIG-I+] Huh7 cells) (46) were maintained in culture as described previously (23). PHHs were obtained from Stephen Strom (University of Pittsburgh) through the NIH-funded Liver Tissue and Cell Distribution System (LTCDS) and maintained in Williams E medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) containing cell maintenance supplement reagents from Invitrogen.

Viruses.

HCV JFH-1 (genotype 2a) stock preparation and titration were performed as described previously (47, 48). Viral stocks were passaged at least twice prior to use in experimental methods. Cell cultures were infected at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.6, 1.0, or 5.0, as previously described (23). Infected hepatocyte cultures were incubated for 12, 18, 24, 26, or 48 h.

Sendai virus (SeV; Cantrell strain; Charles River Laboratories Wilmington, MA) was diluted in serum-free Dulbecco modified Eagle medium, and 100 hemagglutination units (HAU) was added to cells for 1 h to allow virus adsorption. An equivalent amount of normal medium was then added. Infected hepatocyte cultures were incubated for 24 h.

PAMPs.

For specific activation of RIG-I, cells were transfected with 0.2 μg of 5′ pU HCV PAMP RNA from HCV JFH-1 (genotype 2a) or HCV Con1A (genotype 1) using the MATra-A magnetofection reagent (PromoKine, Heidelberg, Germany). SeV infection, as described above, also served as a control for RIG-I activation. Specific activation of TLR3 was achieved by adding 5 μg/ml poly(I·C) (Amersham; now GE Healthcare Life Sciences [Pittsburgh, PA]) to the cell culture medium. With all poly(I·C) and 5′ pU HCV PAMP treatments, cells were incubated for 24 h.

Plasmids.

Firefly luciferase reporter pGL4 plasmids expressing the wild-type, ΔκB1, ΔκB2, ΔAP-1, ΔC/EPB-1, or ΔISRE CXCL10 promoter were provided by David Proud (University of Calgary) (4, 17). A CMV-BL plasmid carrying the constitutively active mutant IRF3 (IRF3-5D) (27, 28) was provided by John Hiscott (McGill University). The empty vector, plasmid pcDNA3.1, was obtained from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA).

Luciferase assays.

For PRR-specific activation, 50 ng of each CXCL10-firefly luciferase reporter plasmid was transfected into cells using MATra-A. After 24 h, exogenous poly(I·C) or transfected 5′ pU HCV PAMP was added to designated wells as described above. Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and 100 ng/ml IFN-γ in combination with 40 ng/ml TNF-α were also added as negative and positive controls, respectively. Luciferase activity was read after an additional 24 h using the BriteLite reagent (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA).

For HCV JFH-1-based activation, CXCL10 plasmids were transfected into cells using the X-treme Gene 9 transfection reagent (Roche, Indianapolis, IN). Cells were then infected at 48 h posttransfection with HCV JFH-1 (MOI, 1.0) or treated with IFN-γ and TNF-α or PBS as described above. Luciferase activity was read after an additional 24 h using the BriteLite reagent. Cell viability in each well during infection was assessed by the use of the CellTiter-Fluor assay (Promega) and used to normalize the luciferase readings.

To evaluate direct activation via IRF3, 50 ng of the plasmid carrying IRF3-5D or pcDNA3.1 was cotransfected with 50 ng of the wild-type or ΔISRE CXCL10 reporter plasmid into cells using MATra-A. B18R protein (2 μg/ml; eBioscience, San Diego, CA) or IL-28B/IL-29-neutralizing antibody (4 μg/ml; MAB15981; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) was then immediately added to the culture medium to neutralize type I IFNs or type III IFNs, respectively (PBS was added to the control samples). After 24 h, luciferase activity was read using the BriteLite reagent and was normalized for cell viability as described above.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation.

Cells were mock infected, infected with SeV for 6 h, or infected with HCV JFH-1 for 12 or 18 h (MOI, 0.6). Chromatin was harvested following formaldehyde fixation and sheared by sonication using an ultrasonic homogenizer probe (4710 series; Cole-Parmer Instrument Co.). Immunoprecipitation was performed on 15 μg of each chromatin preparation using a ChIP Express chromatin immunoprecipitation kit (Active Motif, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Reaction mixtures were incubated overnight using polyclonal rabbit anti-IRF3 serum (Active Motif) or normal rabbit serum (Jackson ImmunoResearch) at equivalent concentrations. Chromatin fragments were PCR amplified using Phusion Hot Start II high-fidelity DNA polymerase (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and primers directed against the ISRE region of the CXCL10 promoter (forward primer 5′-TGGATTGCAACCTTTGTTTTT-3′ and reverse primer 5′-GTCCCATGTTGCAGACTCG-3′; melting temperature, 64°C). Input DNA samples and a reaction mixture with no template were included as positive and negative controls, respectively. PCR products were resolved on a 1% TBE (Tris-borate-EDTA) agarose gel and visualized using a GelDoc system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Bands were quantified using ImageJ software (version 1.46; http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/).

Real-time RT-PCR.

For analysis of endogenous mRNA levels, total RNA was isolated from cells using an RNeasy RNA extraction kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) and cDNA synthesis was performed using 0.5 mg of total RNA (Transcriptor first-strand cDNA synthesis kit; Roche, Basel, Switzerland). Fluorescence real-time PCR analysis was performed using an ABI 7500 instrument (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) and TaqMan 6-carboxyfluorescein-labeled gene expression assays for CXCL10 and ISG15 (IP10-Hs00171042_m1 and ISG15-Hs01921425_s1; Applied Biosystems). The relative amounts of mRNA were normalized to the 18S rRNA levels in each PCR mixture using a eukaryotic 18S rRNA endogenous control (a VIC/MGB probe; catalog number 4319413E; Applied Biosystems). The ΔΔCT threshold cycle (CT) method was used for calculating relative mRNA levels and fold induction.

For virus quantification, total RNA was isolated from whole-cell lysates as described above. The intracellular and extracellular copy numbers of HCV RNA were determined by real-time reverse transcription-PCT (RT-PCR) with the probe, primers, and parameters described previously (49).

CXCL10 ELISAs.

The amount of CXCL10 protein produced by PHHs was measured using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits purchased from RayBiotech (Norcross, GA).

Immunofluorescence.

PHHs grown on Lab-Tek II borosilicate four-well chamber coverslips (Nunc) were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized in 0.3% Triton X-100, and incubated in PBS containing 3% bovine serum albumin (BSA) and 10% normal goat serum (Vector Laboratories). Cells were then labeled with anti-ISG15 (catalog number 2743; Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA) and anti-IRF3 (catalog number ab50772; Abcam, Cambridge, MA) primary antibodies diluted in PBS with 1% BSA, followed by incubation with Alexa Fluor 488-, 568-, or 647-conjugated secondary antibodies (Invitrogen) in PBS with 1% BSA. Nuclei were counterstained with Hoechst 33342 (Invitrogen) at 1:5,000 in PBS. Each step was followed by three washes with PBS.

Confocal laser scanning microscopy analysis was performed with an Axio Observer.Z1 microscope equipped with a Zeiss LSM 5 Live DuoScan system under a ×63 objective oil immersion lens (numerical aperture [NA], 1.4; Carl Zeiss). Two-dimensional projection images were created from z-stacks acquired using ZEN 2009 software (Carl Zeiss). Dual- or triple-color images were acquired by consecutive scanning with only one laser line active per scan to avoid cross excitation.

Statistical methods.

Luciferase reporter data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation, and for each presented experiment, results are representative of those from two independent replicates consisting of three sample replicates each. Chromatin immunoprecipitation data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation of results from three independent experimental replicates. Experiments utilizing primary human hepatocytes were repeated using cells from at least two donors. Statistical analysis of luciferase reporter data were predominantly conducted in Prism software (GraphPad Software, Inc.) using a standard Student's t tests for determining significance.

RESULTS

Positive and negative regulation of the CXCL10 promoter.

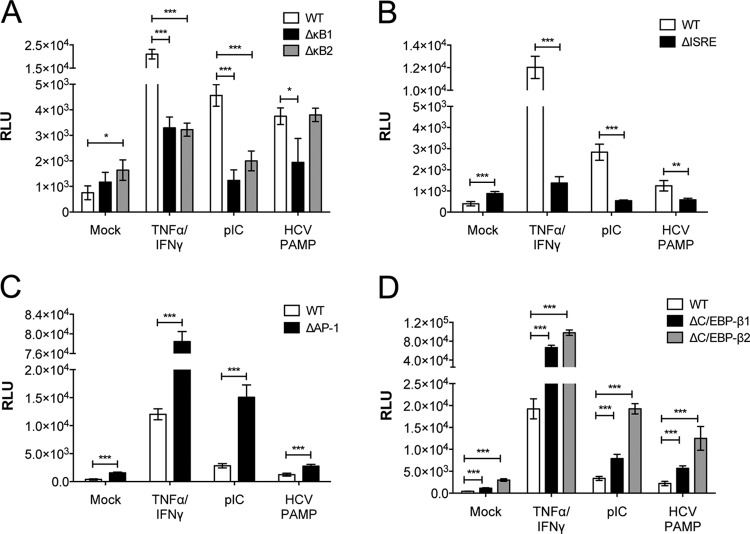

We recently showed that both TLR3 signaling and RIG-I signaling are required for CXCL10 induction in hepatocytes during early HCV infection but that the initial induction did not require type I or type III IFNs (44). Therefore, in this study we sought to identify the transcription factors activated downstream of TLR3 and RIG-I that contribute to HCV-mediated CXCL10 induction. The CXCL10 promoter contains binding sites for multiple transcription factors involved in proinflammatory and antiviral innate immune responses (Fig. 1) (17). In order to evaluate the importance of these factors for TLR3 and RIG-I signaling to CXCL10 induction, luciferase reporter gene constructs driven by either wild-type or mutated CXCL10 promoters were transfected into PH5CH8 immortalized hepatocytes, which express both PRRs (45). The mutated CXCL10 promoters contain point mutations in the proximal ISRE (ΔISRE) as well as in the proximal binding sites for NF-κB (ΔκB1, ΔκB2), AP-1 (ΔAP-1), and C/EPB-β (ΔC/EPB-β1, ΔC/EPB-β2) (17). After 24 h, 1 μg/ml poly(I·C) was added to the culture medium or 0.2 μg 5′ pU HCV PAMP from HCV JFH-1 (genotype 2a) or HCV Con1A (genotype 1) was transfected into cells to activate TLR3 and RIG-I, respectively. Combination treatment with 100 ng/ml IFN-γ and 40 ng/ml TNF-α served as a positive control. The luciferase signal was then measured after an additional 24 h.

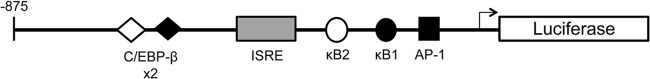

FIG 1.

Schematic of the CXCL10 promoter-luciferase reporter constructs. Putative binding sites for NF-κB, AP-1, C/EBP-β, and the ISRE are labeled.

As expected, the wild-type promoter strongly responded to the IFN-γ–TNF-α treatment as well as both PRR stimuli (Fig. 2). Mutating the more proximal NF-κB site (ΔκB1) significantly reduced these responses (P < 0.05), with the induction from the HCV PAMP and poly(I·C) returning to baseline levels (Fig. 2A). The ΔκB2 mutation also resulted in a significant decrease in the CXCL10 response to IFN-γ–TNF-α and poly(I·C) (P < 0.01). However, no decrease in signal was observed in response to the HCV PAMP, suggesting that NF-κB binding to these sites is stimulus specific. CXCL10 transcription was also significantly decreased in response to all three treatments after mutation of the proximal ISRE (ΔISRE; P < 0.01; Fig. 2B). In contrast, treatment with either PAMP led to an increase in the luciferase signal over that for the wild type for the ΔAP-1, ΔC/EPB-β1, and ΔC/EPB-β2 constructs (P < 0.01; Fig. 2C and D), indicating that AP-1 and C/EBP-β act as negative regulators of CXCL10 induction following TLR3 and RIG-I activation. Treatment with the HCV Con1A PAMP induced a response similar to that of the HCV JFH-1 PAMP, with decreased luciferase activity being obtained for the ΔκB1 and the ΔISRE constructs (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Decreased luciferase activity was also observed for the ΔκB2 construct in response to Con1A treatment (Fig. S1A in the supplemental material).

FIG 2.

NF-κB and the proximal ISRE positively regulate the CXCL10 promoter in response to TLR3 and RIG-I PAMPs. Deletion of the NF-κB (κB1, κB2) (A) or proximal ISRE (B) binding sites eliminates activation of the CXCL10 promoter following 24 h of treatment with either exogenously added poly(I·C) (pIC; 5 μg/ml) or 0.5 μg transfected 5′ pU HCV PAMP (P < 0.05). Deletion of the AP-1 (C) or C/EBP-β (C/EBP-β1, C/EBP-β2) (D) binding site results in increased activity of the CXCL10 promoter in response to these stimuli (P < 0.01). Combination treatment with 100 ng/ml IFN-γ and 40 ng/ml TNF-α for 24 h served as a positive control for induction. Results are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation and are representative of two independent experimental repeats of three sample replicates each. RLU, relative light units. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

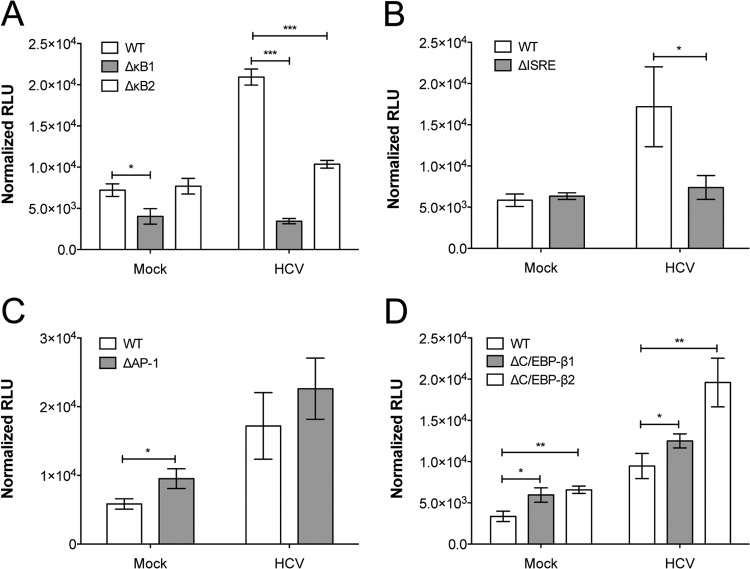

We next evaluated the response of these constructs during HCV infection in TLR3+/RIG-I+ Huh7 hepatoma cells, which also express both RIG-I and TLR3 but are readily susceptible to virus infection in vitro (44). TLR3+/RIG-I+ Huh7 cells were transfected as described above and infected 48 h later with HCV JFH-1 (MOI, 1.0). Luciferase values were read at 24 h postinfection and normalized according to cell viability, which was comparable between mock- and HCV-infected cells (data not shown). Similar to the PAMP treatments, the wild-type CXCL10 promoter responded strongly to HCV infection (Fig. 3). This is consistent with previous observations of CXCL10 mRNA and protein induction during virus infection (37, 39). The ΔκB1, ΔκB2, and ΔISRE promoter responses were also similar to those observed with the PAMPs, showing significant decreases in signal in comparison to that achieved with the wild-type promoter (P < 0.05; Fig. 3A and B). However, the ΔAP-1 promoter response was not significantly different from the wild-type response (P > 0.1; Fig. 3C), contrary to the results from treatments with PAMPs. The increase in CXCL10 induction observed with the ΔC/EPB-β1 construct was also less than that observed during PAMP stimulation, although it remained significantly higher than that observed with the wild-type construct (P < 0.05; Fig. 3D). In contrast, HCV infection and PAMP treatment caused similarly significant fold change increases in CXCL10 induction from the ΔC/EPB-β2 construct (P < 0.01; Fig. 3D).

FIG 3.

NF-κB and the proximal ISRE positively regulate the CXCL10 promoter in response to HCV infection. Deletion of the NF-κB (κB1, κB2) (A) or proximal ISRE (B) binding sites significantly decreased activation of the CXCL10 promoter following 24 h of HCV infection (P < 0.05; MOI, 1.0). (C) Deletion of the AP-1 binding site had no significant effect on the CXCL10 promoter response during HCV infection (P > 0.1). (D) Deletion of the C/EBP-β binding sites (C/EBP-β1, C/EBP-β2) increased the CXCL10 promoter response during HCV infection (P < 0.05). Results are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation and are representative of two independent experimental replicates of three sample replicates each. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01.

IRF3 localizes to the nucleus in HCV-infected PHHs.

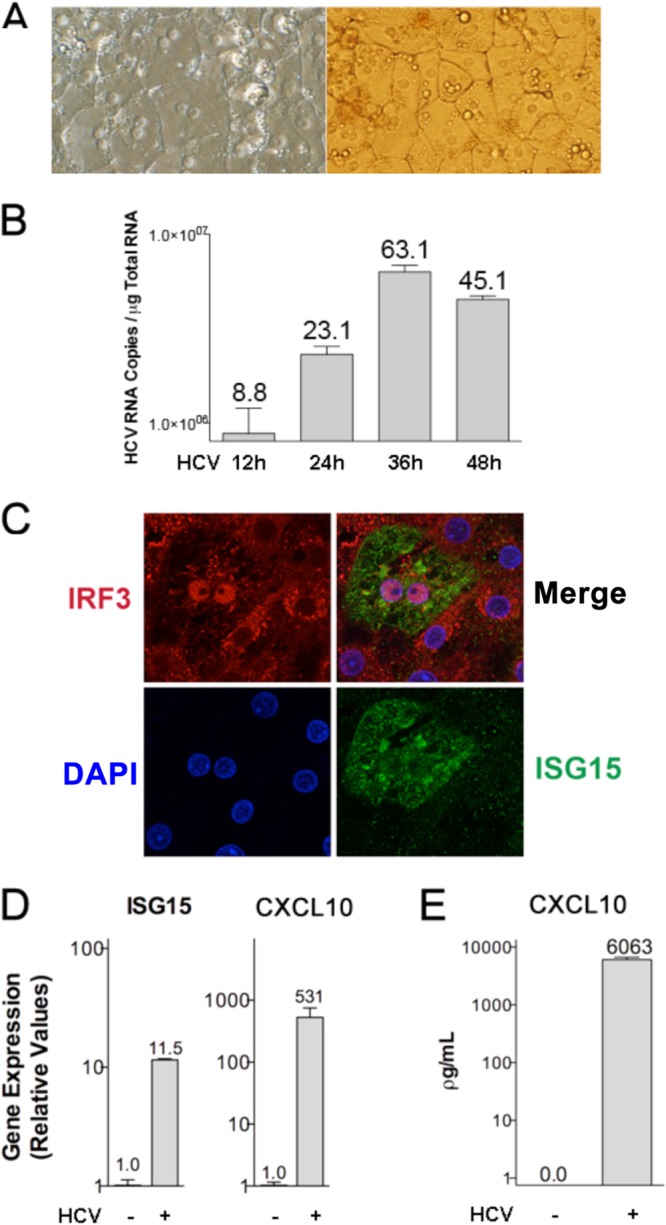

Although type I and type III IFNs induce formation of the ISGF3G complex that binds ISREs (1, 50), we previously observed no contribution of these cytokines to CXCL10 induction in immortalized cell lines, as described above (44). We hypothesized that one or more IRFs may be directly binding to the CXCL10 promoter. IRF3 was selected as a likely candidate on the basis of previous evidence of its binding to the CXCL8 promoter following HCV infection and RIG-I signaling (23). Accordingly, we examined IRF3 activation as well as induction of CXCL10 and the antiviral response in primary human hepatocytes (PHHs) following HCV infection (Fig. 4). PHH cultures (Fig. 4A) were infected with HCV for 12, 24, 36, and 48 h, and a time-dependent increase in intracellular viral RNA was observed from 12 to 36 h (MOI, 5.0; Fig. 4B). Since the level of intracellular viral RNA did not increase after 36 h, we surmised that the antiviral response had been activated. To test this hypothesis, we stained for nuclear IRF3 as well as for the ISG15 protein, which is rapidly upregulated following virus infection (51). Nuclear IRF3 was observed by immunofluorescence in PHHs exposed to HCV (Fig. 4C) but not in mock-infected cells (data not shown). In addition, cells with nuclear IRF3 also had upregulated ISG15 protein levels, demonstrating activation of the antiviral response. Upregulation of ISG15 was confirmed by real-time RT-PCR (Fig. 4D). Furthermore, PHH cultures also showed upregulation of CXCL10 mRNA (Fig. 4D) and protein (Fig. 4E) following HCV infection. These data indicate that HCV infection of PHHs leads to both the activation of IRF3 and the induction of CXCL10.

FIG 4.

HCV infection of PHHs activates IRF3 and the antiviral response. (A) Light microscope images of PHHs; (B) intracellular HCV RNA levels after infection with HCV (MOI, 5.0) for 12, 24, 36, and 48 h; (C) immunofluorescence analysis of IRF3 (red) and ISG15 (green) after infection with HCV (MOI, 5.0) for 24 h; (D) ISG15 and CXCL10 mRNA levels 36 h after infection with HCV (MOI, 5.0); (E) CXCL10 protein levels 36 h after infection with HCV (MOI, 5.0). Results are representative of staining performed with PHHs from two different donors.

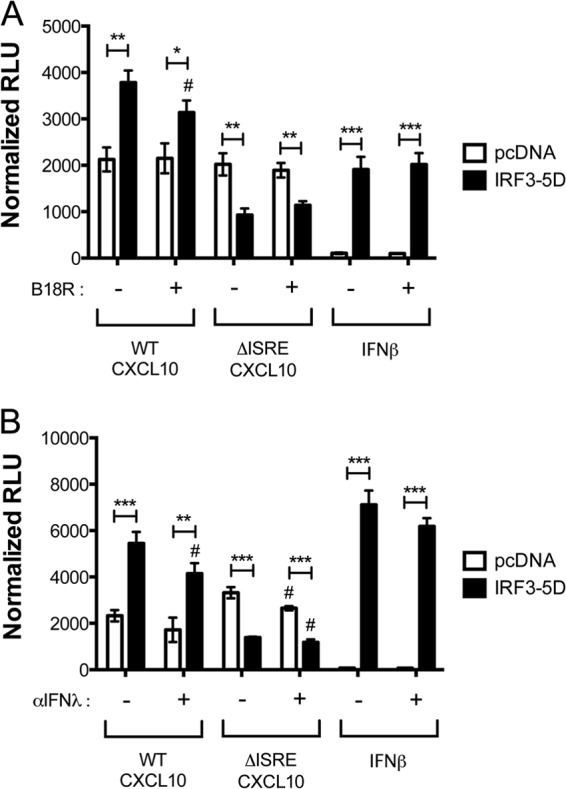

IRF3-5D activates CXCL10 transcription during interferon neutralization.

In order to more directly assess the involvement of IRF3 in the activation of the CXCL10 promoter, a constitutively active mutant form of IRF3 (IRF3-5D) or an empty vector (pcDNA3.1) was cotransfected with the wild-type CXCL10 promoter construct into PH5CH8 immortalized hepatocytes. IRF3-5D was also cotransfected with an IFN-β–luciferase reporter construct as a positive control. Luciferase activity was then read in the presence and absence of a soluble type I IFN receptor (the vaccinia virus protein B18R [52]; Fig. 5A) or a pan-type III IFN-neutralizing antibody (anti-IFN-λ; Fig. 5B) to observe the effects of blocking interferon signaling. The neutralization efficacy of these reagents was demonstrated previously (44). Interferon-neutralized samples were normalized for cell viability as described above. In both systems, IRF3-5D induced transcription of the wild-type CXCL10 and the IFN-β promoter constructs. While the addition of either neutralizing agent significantly reduced CXCL10 induction compared to that achieved under nonneutralizing conditions (P < 0.05), expression during neutralization was still significantly higher than that at the baseline (P < 0.05). Importantly, induction was completely absent without the ISRE (ΔISRE CXCL10 construct), indicating that IRF3 regulates CXCL10 transcription via the ISRE in an IFN-independent manner.

FIG 5.

Constitutively active IRF3 (IRF3-5D) drives CXCL10 transcription independently of type I and type III IFNs. Neutralization of type I IFNs via B18R (A) or type III IFNs via anti-IFN-λ (B) did not impact IRF3-5D-induced wild-type (WT) CXCL10 promoter activity 24 h after cotransfection in PH5CH8 immortalized hepatocytes. IRF3-5D was not able to induce expression of the ΔISRE CXCL10 mutant promoter above background levels induced by a control vector (pcDNA3.1 [pcDNA]). IFN-β promoter responses to IRF3-5D were included as a positive control. Results are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation and are representative of two independent experimental infections of three sample replicates each. #, conditions where addition of B18R or anti-IFN-λ led to a significant change in signal compared to that for nonneutralized samples (P < 0.05); *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

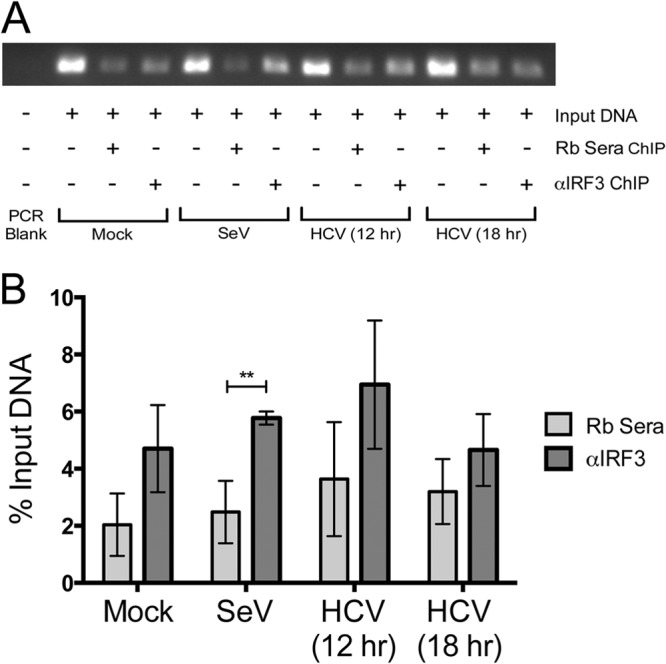

IRF3 binds to the CXCL10 promoter during HCV infection.

To confirm that IRF3 binding to the CXCL10 promoter physically occurs during HCV infection, we performed chromatin immunoprecipitation for IRF3 on TLR3+/RIG-I+ Huh7 cells that were infected with HCV JFH-1 for 12 or 18 h (MOI, 0.6). TLR3+/RIG-I+ Huh7 cells infected with SeV (6 h; 100 HAU), a known RIG-I agonist, were included as a positive experimental control for IRF3 binding (Fig. 6A, SeV). Uninfected cells were included as a negative control (Fig. 6A, Mock). The CXCL10 promoter was detected as bound to IRF3 in cells infected with HCV for 12 h [Fig. 6A, HCV (12 h)]. The level of IRF3 binding was similar to that for the SeV control. This signal was reduced in cells infected with HCV for 18 h [Fig. 6A, HCV (18 h)]. This trend was also observed in two additional experimental replicates, although the averaged data did not achieve statistical significance (P = 0.1; Fig. 6B). Thus, these data suggest that IRF3 is rapidly recruited to the CXCL10 promoter during both Sendai virus and HCV infection of hepatocytes. Furthermore, IRF3 recruitment seems to be transient during HCV infection.

FIG 6.

IRF3 is recruited to the CXCL10 promoter during HCV infection. (A) Representative gel image of PCR products resulting from chromatin immunoprecipitation of TLR3+/RIG-I+ Huh7 cells infected with HCV (12 and 18 h; MOI, 0.6) or SeV (6 h; 100 HAU) using polyclonal anti-IRF3 serum. Normal rabbit serum (Rb Sera) was used as a negative control. Isolated chromatin fragments were PCR amplified using primers specific for the proximal ISRE of the CXCL10 promoter and resolved on an agarose gel. Input DNA was used as a positive control during PCR. Increased IRF3 binding to the CXCL10 promoter was detected during SeV infection and after 12 h of HCV infection. IRF3 binding returned to baseline levels 18 h after HCV infection. (B) Quantification of CXCL10 ISRE PCR band intensities expressed as a percentage of input DNA. Data were averaged from the results of three independent chromatin immunoprecipitation preparations. **, P < 0.01.

DISCUSSION

Binding sites for a wide variety of transcription factors have been annotated within the CXCL10 promoter, including NF-κB, AP-1, C/EBP-β, and IRFs (17). In the current study, we demonstrated for the first time that AP-1 and C/EBP-β are negative or neutral regulators of CXCL10 induction. The observed negative or neutral regulation occurred in a PAMP-dependent manner, which is summarized in Table 1. We also confirmed previous reports that NF-κB is a critical positive regulator of CXCL10 during HCV infection and PRR activation. While both annotated NF-κB binding sites were required for CXCL10 transcription in response to the HCV Con1A (genotype 1) PAMP, only κB1 was required for transcription following treatment with the HCV JFH-1 (genotype 2) PAMP. This subtle distinction may reflect genotype-specific differences in RIG-I binding and activation as a result of sequence variations between these two PAMPs (53).

TABLE 1.

PAMP-dependent effects of transcription factor binding to the CXCL10 promoter

| Transcription factor | Effect on CXCL10 promotera |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| HCV PAMP | Poly(I·C) | HCV infection | |

| NF-κB | +++ | +++ | +++ |

| IRF3 | +++ | +++ | +++ |

| AP-1 | −− | −− | NE |

| C/EBP-β | −− | −− | − |

The proposed effect of each transcription factor on CXCL10 promoter activation in response to transfected HCV PAMP, exogenously added poly(I·C), or HCV infection (MOI, 1.0; 24 h). The listed effects are extrapolated on the basis of the results presented for mutated CXCL10 promoters in Fig. 2 and 3. NE, no effect; +, induction; −, repression. +++, strong positive regulation; −−, moderate negative regulation; −, minor negative regulation.

The ISRE most proximal to the CXCL10 transcriptional start site was an additional site of strong positive regulation, and our chromatin immunoprecipitation assays suggest that IRF3 binds this site during acute HCV infection of human hepatoma cells. These data are supported by previous reports of IRF3 binding to the CXCL10 promoter in A549 alveolar carcinoma cells following influenza A virus infection (54). In the present study, IRF3 activation and nuclear translocation were also observed during HCV infection of PHHs. Furthermore, IRF3-driven CXCL10 transcription in immortalized hepatoma cells was independent of signaling by type I or type III IFNs. Taken together, these data indicate that CXCL10 induction during both early HCV infection and PRR-specific stimulation is predominantly mediated by NF-κB and IRF3, with minor negative modulation by AP-1 and C/EBP-β occurring (Table 1).

Although AP-1 and C/EBP-β are typically considered positive regulators of gene expression, instances of negative regulation have also been documented. C/EBP-β has been shown to negatively regulate transcription of the tumor suppressor microRNA miR-145 in breast cancer cells (55). There is also evidence that C/EBP-β inhibits collagen synthesis in fibroblasts in response to type II IFN and extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 (ERK1/2) MAP kinase signaling (56). Similarly, Fos/Jun AP-1 heterodimers have been shown to negatively regulate transcription of the steroidogenic enzyme CYP17 following ERK1/2 activation (57), while IL-4 is negatively regulated by the JunD AP-1 homodimer (30). Given the vast array of subunits that can comprise AP-1, other less well studied heterodimers may also negatively regulate the induction of target genes. Different heterodimers could also be activated in response to different stimuli. This could potentially explain the differential effect of AP-1 on CXCL10 induction during treatment with PRR-specific PAMPs (negative regulation) in comparison to that during early HCV infection (no significant regulatory effect).

Induction of CXCL10 in hepatocytes may also be influenced by transcription factors not surveyed in our study. For example, type II IFN (i.e., IFN-γ) signaling leads to the formation of STAT1 homodimers that bind to gamma interferon activation site (GAS) elements in ISGs (8). Type II IFN is the canonical inducer of CXCL10 produced by proinflammatory immune effector cells, and GAS elements have recently been identified within the CXCL10 promoter (58, 59). However, production of type II IFNs has been documented only in professional immune cells, and we previously showed that this cytokine did not contribute to CXCL10 induction in HCV-infected PHH cultures that were depleted of immune effector and nonparenchymal cells (9, 44). This suggests that type II IFN does not contribute to CXCL10 induction in the hepatocyte monocultures utilized here, although it likely contributes to CXCL10 induction during the later stages of acute and then chronic HCV infection of the whole liver in vivo.

In addition, other IRFs besides IRF3 may bind the proximal ISRE in the CXCL10 promoter, and previous studies have shown that IRF1 and IRF7 bind directly to this site in lung epithelial cells following influenza A virus infection (43). However, it remains unknown whether these IRFs bind chemokine promoters in hepatocytes following HCV infection. The ISRE-binding ISGF3 complex may also compete with IRF3 for binding to the proximal CXCL10 ISRE during late acute and chronic hepatitis C when type I and type III IFNs are abundant in the liver (50). Alternatively, ISGF3 and other IRFs may bind ISREs annotated further upstream within the CXCL10 promoter and work synergistically with IRF3 to promote CXCL10 induction (17). However, ISGF3 is unlikely to play a central role in our experimental system, since type I and type III IFNs were neutralized during instances of significant CXCL10 induction by IRF3-5D (Fig. 3).

Nontraditional signaling pathways may also be responsible for activation of transcription factors that drive CXCL10 induction. Ho and colleagues reported IFN-independent activation of STAT1 and STAT3 proteins during infection with dengue virus, another member of the Flaviviridae (60). STAT1 can also be activated via p38 MAP kinase following TLR7 stimulation in plasmacytoid dendritic cells (61). As STAT1 can bind to both ISREs and GAS elements, it is possible that this alternative pathway also contributes to CXCL10 induction during early HCV infection, although this has not yet been shown experimentally. It also remains to be demonstrated whether IFN-independent STAT activation can be induced following TLR3 and RIG-I signaling in hepatocytes.

In summary, our results indicate that NF-κB and IRF3 are crucial regulators of the CXCL10 response during early HCV infection in hepatocytes and that this response can be partially downregulated by AP-1 and C/EBP-β. Other transcription factors, including other IRFs and STAT proteins, may also modulate this response. Antagonism of any of these factors by viral proteins during early HCV infection (62) could interfere with CXCL10 induction and alter the character of the initial innate immune response to one that favors perpetual inflammation and viral persistence. For example, the HCV NS5a protein alone can induce NF-κB-mediated activation of genes that can contribute to the development of interferon resistance, fibrosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma (63). HCV has also been shown to prevent nuclear translocation of activated IRF7 during later stages of infection (64), and the core protein specifically is known to inhibit IRF3 dimerization and activation of IFN-β transcription (65). Further elucidation of the complex and combinational mechanisms behind transcriptional control of CXCL10 may help to identify novel targets for host-oriented therapies for controlling the persistent and damaging liver inflammation that is characteristic of chronic hepatitis C.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH U19AI066328, AI069285) and a pathobiology predoctoral training grant from the University of Washington (NIH 2T32AI007509).

We thank Hugo Rosen and Young Hahn for helpful discussions and Dennis Sorta for technical assistance.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 20 November 2013

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JVI.02007-13.

REFERENCES

- 1.Takeuchi O, Akira S. 2010. Pattern recognition receptors and inflammation. Cell 140:805–820. 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eksioglu EA, Zhu H, Bayouth L, Bess J, Liu H-Y, Nelson DR, Liu C. 2011. Characterization of HCV interactions with Toll-like receptors and RIG-I in liver cells. PLoS One 6:e21186. 10.1371/journal.pone.0021186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dolganiuc A, Oak S, Kodys K, Golenbock DT, Finberg RW, Kurt-Jones E, Szabo G. 2004. Hepatitis C core and nonstructural 3 proteins trigger Toll-like receptor 2-mediated pathways and inflammatory activation. Gastroenterology 127:1513–1524. 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.08.067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li K, Li NL, Wei D, Pfeffer SR, Fan M, Pfeffer LM. 2012. Activation of chemokine and inflammatory cytokine response in hepatitis C virus-infected hepatocytes depends on Toll-like receptor 3 sensing of hepatitis C virus double-stranded RNA intermediates. Hepatology 55:666–675. 10.1002/hep.24763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saito T, Owen DM, Jiang F, Marcotrigiano J, Gale M. 2008. Innate immunity induced by composition-dependent RIG-I recognition of hepatitis C virus RNA. Nature 454:523–527. 10.1038/nature07106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ank N, West H, Paludan SR. 2006. IFN-lambda: novel antiviral cytokines. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 26:373–379. 10.1089/jir.2006.26.373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kawai T, Akira S. 2008. Toll-like receptor and RIG-1-like receptor signaling. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1143:1–20. 10.1196/annals.1443.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aaronson DS, Horvath CM. 2002. A road map for those who don't know JAK-STAT. Science 296:1653–1655. 10.1126/science.1071545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schroder K, Hertzog PJ, Ravasi T, Hume DA. 2004. Interferon-gamma: an overview of signals, mechanisms and functions. J. Leukoc. Biol. 75:163–189. 10.1189/jlb.0603252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Banerjee A, Gerondakis S. 2007. Coordinating TLR-activated signaling pathways in cells of the immune system. Immunol. Cell Biol. 85:420–424. 10.1038/sj.icb.7100098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yu M, Levine SJ. 2011. Toll-like receptor 3, RIG-I-like receptors and the NLRP3 inflammasome: key modulators of innate immune responses to double-stranded RNA viruses. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 22:63–72. 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2011.02.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jiang Z, Zamanian-Daryoush M, Nie H, Silva AM, Williams BRG, Li X. 2003. Poly(I-C)-induced Toll-like receptor 3 (TLR3)-mediated activation of NFkappa B and MAP kinase is through an interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase (IRAK)-independent pathway employing the signaling components TLR3-TRAF6-TAK1-TAB2-PKR. J. Biol. Chem. 278:16713–16719. 10.1074/jbc.M300562200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mikkelsen SS, Jensen SB, Chiliveru S, Melchjorsen J, Julkunen I, Gaestel M, Arthur JSC, Flavell RA, Ghosh S, Paludan SR. 2009. RIG-I-mediated activation of p38 MAPK is essential for viral induction of interferon and activation of dendritic cells: dependence on TRAF2 and TAK1. J. Biol. Chem. 284:10774–10782. 10.1074/jbc.M807272200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Whitmarsh AJ, Davis RJ. 1996. Transcription factor AP-1 regulation by mitogen-activated protein kinase signal transduction pathways. J. Mol. Med. 74:589–607. 10.1007/s001090050063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang S-H, Sharrocks AD, Whitmarsh AJ. 2013. MAP kinase signalling cascades and transcriptional regulation. Gene 513:1–13. 10.1016/j.gene.2012.10.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kalvakolanu DV, Roy SK. 2005. CCAAT/enhancer binding proteins and interferon signaling pathways. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 25:757–769. 10.1089/jir.2005.25.757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Spurrell JCL, Wiehler S, Zaheer RS, Sanders SP, Proud D. 2005. Human airway epithelial cells produce IP-10 (CXCL10) in vitro and in vivo upon rhinovirus infection. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 289:L85–L95. 10.1152/ajplung.00397.2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zeremski M, Petrovic LM, Chiriboga L, Brown QB, Yee HT, Kinkhabwala M, Jacobson IM, Dimova R, Markatou M, Talal AH. 2008. Intrahepatic levels of CXCR3-associated chemokines correlate with liver inflammation and fibrosis in chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology 48:1440–1450. 10.1002/hep.22500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Larrubia J-R, Calvino M, Benito S, Sanz-de-Villalobos E, Perna C, Pérez-Hornedo J, González-Mateos F, García-Garzón S, Bienvenido A, Parra T. 2007. The role of CCR5/CXCR3 expressing CD8+ cells in liver damage and viral control during persistent hepatitis C virus infection. J. Hepatol. 47:632–641. 10.1016/j.jhep.2007.04.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Darling JM, Aerssens J, Fanning G, McHutchison JG, Goldstein DB, Thompson AJ, Shianna KV, Afdhal NH, Hudson ML, Howell CD, Talloen W, Bollekens J, De Wit M, Scholliers A, Fried MW. 2011. Quantitation of pretreatment serum interferon-γ-inducible protein-10 improves the predictive value of an IL28B gene polymorphism for hepatitis C treatment response. Hepatology 53:14–22. 10.1002/hep.24056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lagging M, Askarieh G, Negro F, Bibert S, Söderholm J, Westin J, Lindh M, Romero A, Missale G, Ferrari C, Neumann AU, Pawlotsky J-M, Haagmans BL, Zeuzem S, Bochud P-Y, Hellstrand K, DITTO-HCV Study Group 2011. Response prediction in chronic hepatitis C by assessment of IP-10 and IL28B-related single nucleotide polymorphisms. PLoS One 6:e17232. 10.1371/journal.pone.0017232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Askarieh G, Alsiö A, Pugnale P, Negro F, Ferrari C, Neumann AU, Pawlotsky J-M, Schalm SW, Zeuzem S, Norkrans G, Westin J, Söderholm J, Hellstrand K, Lagging M, DITTO-HCV and NORDynamIC Study Groups 2010. Systemic and intrahepatic interferon-gamma-inducible protein 10 kDa predicts the first-phase decline in hepatitis C virus RNA and overall viral response to therapy in chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology 51:1523–1530. 10.1002/hep.23509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wagoner J, Austin M, Green J, Imaizumi T, Casola A, Brasier A, Khabar KSA, Wakita T, Gale M, Polyak SJ. 2007. Regulation of CXCL-8 (interleukin-8) induction by double-stranded RNA signaling pathways during hepatitis C virus infection. J. Virol. 81:309–318. 10.1128/JVI.01411-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bonizzi G, Karin M. 2004. The two NF-kappaB activation pathways and their role in innate and adaptive immunity. Trends Immunol. 25:280–288. 10.1016/j.it.2004.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baeuerle PA, Baltimore D. 1988. I kappa B: a specific inhibitor of the NF-kappa B transcription factor. Science 242:540–546. 10.1126/science.3140380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kanarek N, Ben-Neriah Y. 2012. Regulation of NF-κB by ubiquitination and degradation of the IκBs. Immunol. Rev. 246:77–94. 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2012.01098.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lin R, Heylbroeck C, Pitha PM, Hiscott J. 1998. Virus-dependent phosphorylation of the IRF-3 transcription factor regulates nuclear translocation, transactivation potential, and proteasome-mediated degradation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18:2986–2996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hess J, Angel P, Schorpp-Kistner M. 2004. AP-1 subunits: quarrel and harmony among siblings. J. Cell Sci. 117:5965–5973. 10.1242/jcs.01589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hartenstein B, Teurich S, Hess J, Schenkel J, Schorpp-Kistner M, Angel P. 2002. Th2 cell-specific cytokine expression and allergen-induced airway inflammation depend on JunB. EMBO J. 21:6321–6329. 10.1093/emboj/cdf648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meixner A, Karreth F, Kenner L, Wagner EF. 2004. JunD regulates lymphocyte proliferation and T helper cell cytokine expression. EMBO J. 23:1325–1335. 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Williams SC, Cantwell CA, Johnson PF. 1991. A family of C/EBP-related proteins capable of forming covalently linked leucine zipper dimers in vitro. Genes Dev. 5:1553–1567. 10.1101/gad.5.9.1553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Poli V. 1998. The role of C/EBP isoforms in the control of inflammatory and native immunity functions. J. Biol. Chem. 273:29279–29282. 10.1074/jbc.273.45.29279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lu Y-C, Kim I, Lye E, Shen F, Suzuki N, Suzuki S, Gerondakis S, Akira S, Gaffen SL, Yeh W-C, Ohashi PS. 2009. Differential role for c-Rel and C/EBPbeta/delta in TLR-mediated induction of proinflammatory cytokines. J. Immunol. 182:7212–7221. 10.4049/jimmunol.0802971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang Z, Bryan JL, DeLassus E, Chang L-W, Liao W, Sandell LJ. 2010. CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein {beta} and NF-{kappa}B mediate high level expression of chemokine genes CCL3 and CCL4 by human chondrocytes in response to IL-1{beta}. J. Biol. Chem. 285:33092–33103. 10.1074/jbc.M110.130377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.John AE, Zhu YM, Brightling CE, Pang L, Knox AJ. 2009. Human airway smooth muscle cells from asthmatic individuals have CXCL8 hypersecretion due to increased NF-kappa B p65, C/EBP beta, and RNA polymerase II binding to the CXCL8 promoter. J. Immunol. 183:4682–4692. 10.4049/jimmunol.0803832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Haim K, Weitzenfeld P, Meshel T, Ben-Baruch A. 2011. Epidermal growth factor and estrogen act by independent pathways to additively promote the release of the angiogenic chemokine CXCL8 by breast tumor cells. Neoplasia 13:230–243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thomas E, Gonzalez VD, Li Q, Modi AA, Chen W, Noureddin M, Rotman Y, Liang TJ. 2012. HCV infection induces a unique hepatic innate immune response associated with robust production of type III interferons. Gastroenterology 142:978–988. 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.12.055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zimmermann HW, Seidler S, Gassler N, Nattermann J, Luedde T, Trautwein C, Tacke F. 2011. Interleukin-8 is activated in patients with chronic liver diseases and associated with hepatic macrophage accumulation in human liver fibrosis. PLoS One 6:e21381. 10.1371/journal.pone.0021381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Helbig KJ, Ruszkiewicz A, Lanford RE, Berzsenyi MD, Harley HA, McColl SR, Beard MR. 2009. Differential expression of the CXCR3 ligands in chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection and their modulation by HCV in vitro. J. Virol. 83:836–846. 10.1128/JVI.01388-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Akbar H, Idrees M, Butt S, Awan Z, Sabar MF, Rehaman IU, Hussain A, Saleem S. 2011. High baseline interleukine-8 level is an independent risk factor for the achievement of sustained virological response in chronic HCV patients. Infect. Genet. Evol. 11:1301–1305. 10.1016/j.meegid.2011.04.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Casola A, Garofalo RP, Jamaluddin M, Vlahopoulos S, Brasier AR. 2000. Requirement of a novel upstream response element in respiratory syncytial virus-induced IL-8 gene expression. J. Immunol. 164:5944–5951 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Koetzler R, Zaheer RS, Wiehler S, Holden NS, Giembycz MA, Proud D. 2009. Nitric oxide inhibits human rhinovirus-induced transcriptional activation of CXCL10 in airway epithelial cells. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 123:201–208.e9. 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.09.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Veckman V, Osterlund P, Fagerlund R, Melén K, Matikainen S, Julkunen I. 2006. TNF-alpha and IFN-alpha enhance influenza-A-virus-induced chemokine gene expression in human A549 lung epithelial cells. Virology 345:96–104. 10.1016/j.virol.2005.09.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brownell J, Wagoner J, Lovelace ES, Thirstrup D, Mohar I, Smith W, Giugliano S, Li K, Crispe IN, Rosen HR, Polyak SJ. 2013. Independent, parallel pathways to CXCL10 induction in HCV-infected hepatocytes. J. Hepatol. 59:701–708. 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.06.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li K, Chen Z, Kato N, Gale M, Lemon SM. 2005. Distinct poly(I-C) and virus-activated signaling pathways leading to interferon-beta production in hepatocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 280:16739–16747. 10.1074/jbc.M414139200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang N, Liang Y, Devaraj S, Wang J, Lemon SM, Li K. 2009. Toll-like receptor 3 mediates establishment of an antiviral state against hepatitis C virus in hepatoma cells. J. Virol. 83:9824–9834. 10.1128/JVI.01125-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhong J, Gastaminza P, Cheng G, Kapadia S, Kato T, Burton DR, Wieland SF, Uprichard SL, Wakita T, Chisari FV. 2005. Robust hepatitis C virus infection in vitro. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102:9294–9299. 10.1073/pnas.0503596102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wakita T, Pietschmann T, Kato T, Date T, Miyamoto M, Zhao Z, Murthy K, Habermann A, Kräusslich H-G, Mizokami M, Bartenschlager R, Liang TJ. 2005. Production of infectious hepatitis C virus in tissue culture from a cloned viral genome. Nat. Med. 11:791–796. 10.1038/nm1268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li Q, Brass AL, Ng A, Hu Z, Xavier RJ, Liang TJ, Elledge SJ. 2009. A genome-wide genetic screen for host factors required for hepatitis C virus propagation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106:16410–16415. 10.1073/pnas.0907439106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhou Z, Hamming OJ, Ank N, Paludan SR, Nielsen AL, Hartmann R. 2007. Type III interferon (IFN) induces a type I IFN-like response in a restricted subset of cells through signaling pathways involving both the Jak-STAT pathway and the mitogen-activated protein kinases. J. Virol. 81:7749–7758. 10.1128/JVI.02438-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Arnaud N, Dabo S, Akazawa D, Fukasawa M, Shinkai-Ouchi F, Hugon J, Wakita T, Meurs EF. 2011. Hepatitis C virus reveals a novel early control in acute immune response. PLoS Pathog. 7:e1002289. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Alcamí A, Symons JA, Smith GL. 2000. The vaccinia virus soluble alpha/beta interferon (IFN) receptor binds to the cell surface and protects cells from the antiviral effects of IFN. J. Virol. 74:11230–11239. 10.1128/JVI.74.23.11230-11239.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schnell G, Loo Y-M, Marcotrigiano J, Gale M. 2012. Uridine composition of the poly-U/UC tract of HCV RNA defines non-self recognition by RIG-I. PLoS Pathog. 8:e1002839. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002839 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lu X, Masic A, Liu Q, Zhou Y. 2011. Regulation of influenza A virus induced CXCL-10 gene expression requires PI3K/Akt pathway and IRF3 transcription factor. Mol. Immunol. 48:1417–1423. 10.1016/j.molimm.2011.03.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sachdeva M, Liu Q, Cao J, Lu Z, Mo Y-Y. 2012. Negative regulation of miR-145 by C/EBP-β through the Akt pathway in cancer cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 40:6683–6692. 10.1093/nar/gks324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ghosh AK, Bhattacharyya S, Mori Y, Varga J. 2006. Inhibition of collagen gene expression by interferon-gamma: novel role of the CCAAT/enhancer binding protein beta (C/EBPbeta). J. Cell. Physiol. 207:251–260. 10.1002/jcp.20559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sirianni R, Nogueira E, Bassett MH, Carr BR, Suzuki T, Pezzi V, ò S, Rainey WE. 2010. The AP-1 family member FOS blocks transcriptional activity of the nuclear receptor steroidogenic factor 1. J. Cell Sci. 123:3956–3965. 10.1242/jcs.055806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Saha B, Jyothi Prasanna S, Chandrasekar B, Nandi D. 2010. Gene modulation and immunoregulatory roles of interferon gamma. Cytokine 50:1–14. 10.1016/j.cyto.2009.11.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Luster AD, Ravetch JV. 1987. Biochemical characterization of a gamma interferon-inducible cytokine (IP-10). J. Exp. Med. 166:1084–1097. 10.1084/jem.166.4.1084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ho L-J, Hung L-F, Weng C-Y, Wu W-L, Chou P, Lin Y-L, Chang D-M, Tai T-Y, Lai J-H. 2005. Dengue virus type 2 antagonizes IFN-alpha but not IFN-gamma antiviral effect via down-regulating Tyk2-STAT signaling in the human dendritic cell. J. Immunol. 174:8163–8172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Di Domizio J, Blum A, Gallagher-Gambarelli M, Molens J-P, Chaperot L, Plumas J. 2009. TLR7 stimulation in human plasmacytoid dendritic cells leads to the induction of early IFN-inducible genes in the absence of type I IFN. Blood 114:1794–1802. 10.1182/blood-2009-04-216770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Heim MH. 2013. Innate immunity and HCV. J. Hepatol. 58:564–574. 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Girard S, Vossman E, Misek DE, Podevin P, Hanash S, Bréchot C, Beretta L. 2004. Hepatitis C virus NS5A-regulated gene expression and signaling revealed via microarray and comparative promoter analyses. Hepatology 40:708–718. 10.1002/hep.20371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Raychoudhuri A, Shrivastava S, Steele R, Dash S, Kanda T, Ray R, Ray RB. 2010. Hepatitis C virus infection impairs IRF-7 translocation and alpha interferon synthesis in immortalized human hepatocytes. J. Virol. 84:10991–10998. 10.1128/JVI.00900-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Inoue K, Tsukiyama-Kohara K, Matsuda C, Yoneyama M, Fujita T, Kuge S, Yoshiba M, Kohara M. 2012. Impairment of interferon regulatory factor-3 activation by hepatitis C virus core protein basic amino acid region 1. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 428:494–499. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.10.079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.