Abstract

Nanoengineered metallic materials have been shown to have a number of exclusive physicochemical properties not available at neither larger (micro- and macroscopic) nor smaller (molecular) scales. Recently, these materials in particular have drawn significant attention due to their capability to enhance fluorescent signals of nearby fluorescent species through a phenomenon known as metal enhanced fluorescence (MEF). MEF originates from the localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR), a collective oscillation of conduction-band electrons that can modify both the extinction coefficient and quantum yield of adjacent fluorescent molecules/species. [1] The extinction coefficient is a function of the electromagnetic field intensity experienced by the fluorescent molecules, and under an enhanced electromagnetic field, fluorescent molecules absorb photons and promote electrons into excited states at accelerated rates. LSPR of metallic nanostructures can also modify the quantum yield of fluorescent species by increasing their radioactive decay rate. The combined enhancement of extinction coefficient and quantum yield can result in significantly strengthened fluorescence from fluorescent species.

Keywords: metal enhanced fluorescence, quantum dot (QD), nanoporous gold (NPG)

Most MEF materials developed thus far are targeted for enhancing fluorescence from organic fluorophores, [2–6] and few have been developed for inorganic fluorescent species such as quantum dots (QDs). [7–12] QDs are distinguished by size-tuneable spectra, large Stokes shifts, high quantum yields and great photostability. [13, 14] These properties make QDs a desirable candidate for applications in biomolecular sensing [15–17] and cellular imaging. [18, 19] Although MEF can improve the detection sensitivity and imaging quality, wide implementation in bioassays is obstructed by technological limitations. In particular, fabrication of metallic nanostructures for MEF is often not scalable due to the requirement of sophisticated equipment and highly specialized personnel. [10, 20] Furthermore, conventional MEF materials, such as nanoantennas, [5, 20] nanorods [8] and nanoparticles [1, 6, 21–24] induce large fluorescence enhancements only at nanoscopic “hot spots”. [22] Since the sparse hot spots constitute only a small fraction of the surface area, the majority of molecules reside outside the active region and do not experience MEF. This results in a low overall enhancement that is impractical for ensemble fluorescence assays, such as microarrays and immunoassays, in which signals are measured across the entire substrate area.

In this report, we demonstrate that a three-dimensional free-standing nanoporous gold (NPG) film can greatly enhance QD fluorescence. NPG was fabricated by a one-step etching process, eliminating the need for a sophisticated nanolithography facility. Strong near-field excitation induced by NPG enabled ~100-fold enhancement of QD fluorescence, the highest demonstrated value to our knowledge. Strong MEF was observed across the entire NPG substrate comprising dense and uniform nanoporous structures. The broad active region of MEF makes NPG perfectly appropriate for ensemble fluorescence assays. In addition, MEF by NPG significantly improved fluorescence imaging of QDs at the single dot level. Different QDs were found to have different optimum pore sizes for maximum enhancement; the QD525 was best enhanced by 38 nm NPG whereas QD605 by 51 nm NPG. Importantly, the pore size of NPG can be tailored to a specific QD species by simply adjusting etching time.

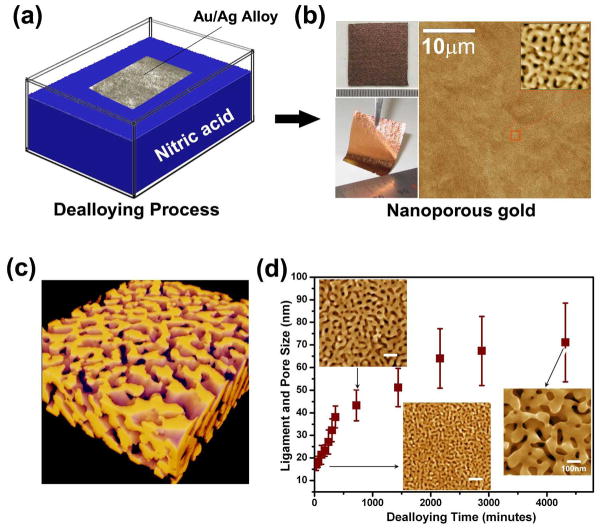

We fabricated NPG films with various pore sizes ranging from 17 nm to 71 nm in average diameter. The NPG films were prepared by selectively etching Ag from 700 nm thick Ag65Au35 (at. %) sheets using saturated nitric acid at room temperature (Figure 1a and b). [25, 26] As nitric acid etches silver atoms away from the alloy, a bicontinuous nanoporous structure with interconnected nanometer-sized pores and gold ligaments is formed by self-assembly of residual gold atoms (Figure 1c). The as-prepared NPG films were carefully rinsed with distilled water. The pore sizes, defined by the equivalent diameters of nanopore channels or gold ligaments, can be tailored from several nanometers to hundred nanometers by controlling the etching time and temperature. [26] The dependence of the pore size on the etching time is illustrated in Figure 1d. Unlike lithography-based nanomaterials, which may suffer from non-uniform UV and temperature exposure, NPG exhibits a uniform nanoporous structure with identical ligaments and nanopores across the entire substrate (Figure 1c). Such high uniformity and broad coverage of nanopores contribute to robust fluorescence detection for ensemble measurements as well as single QD imaging. [27]

Figure 1.

Fabrication and microstructure of dealloyed nanoporous gold. (a) Schematic of the fabrication process of NPG substrates (b) Photographs and microstructure of as-prepared NPG films. (c) 3D electron tomographic image of a representative NPG film. (d) Tunable ligament and pore sizes as a function of etching time. The insets are the top-view SEM micrographs of NPG films with different pore sizes.

We demonstrated the fluorescence enhancing properties of NPG on two QD species, QD605 (peak emission at 605 nm) and QD525 (peak emission at 525 nm). Both QD species are conjugated with streptavidin and have been widely used in biomolecular sensing and diagnostics. [28] Here, the protein coating additionally serves as a spacer to prevent metal induced quenching by NPG. [7] The distance between QDs and NPG, given by streptavidin, is ~5 nm which falls into the optimal spacer distance (~5–10 nm) for best fluorescence enhancements without obvious quench effect.[1, 29] We used TEM to examine the deposition of QDs on the porous surface of NPG after incubation with a 2 nM QD solution (Figure 2). Individual QDs were homogeneously deposited over the porous structure without detectable aggregation. The semiconductor core of QD605 exhibits an oval shape with a size of 5 nm × 12 nm while QD525 exhibits a round shape with a diameter of 5 nm.

Figure 2.

TEM images of quantum dots assembled in the nanopore channels of NPG: (a) QD605; and (b) QD525. 2nM QD aqueous solution is used in the experiment.

Fluorescence enhancement was first evaluated at the single QD level. Figure 3a and d show fluorescence images of QDs on NPG taken by a basic far-field fluorescence microscope equipped with a CCD camera. Real-time imaging of the QDs reveals the blinking characteristics of single QD fluorescence (Figure 3b and e). The fluorescence intensity of individual QDs was determined by the difference in signal level between the “on” and “off” states. It is worth noting that all the single QD signals observed in this study have a constant fluorescence intensity at the “on” and “off” states. This simply rules out the possibility that the individual bright fluorescence spots come from two or three different QDs. Figure 3c and f are box plots of fluorescence intensity of individual QDs on NPG substrates with different pore sizes. The result suggests that there is an optimum NPG pore size for each of the QDs. The best enhancement for QD605 was seen from the NPG substrate with a 51 nm pore size while QD525 was best enhanced by a pore size of 38 nm. The phenomenon was also confirmed by the fluorescence intensity histogram of QD605 and QD525 on NPG (see Figure S1 in Supporting Information). Similar to previous studies on single molecule fluorescence enhancements, [20, 30] a large variation in fluorescence intensity of individual QDs was observed with respect to a specific pore size (Figure 3c and f), which was attributed to the random circumstance of individual QDs on the NPG substrate with irregular shapes of nanopores. Because polarized excitation light is used in the fluorescence imaging in this study, only QDs with dipoles well aligned with the polarization of excitation light are best excited while QDs with dipoles vertical to the excitation light polarization cannot be excited regardless of fluorescence enhancement effects. Additionally, the random nanoscopic structure of the NPG film can also induce intensity variation of the LSPR and lead to diverse orientation and distance of QDs to the NPG surface, further contributing to the variation in fluorescence intensity of individual QDs.

Figure 3.

Measurements of fluorescence enhancement of single QDs as a function of pore sizes of NPG. (a) Fluorescence image of QD605 on NPG. (b) A 10ms trace of single QD605 fluorescence. The sudden intensity change (on-off) as a result of fluorescent blinking is characteristic of single QD fluorescence. (c) Box plot of single QD605 fluorescence intensity on NPG of various pore sizes. The fluorescence intensity of each QD is determined as the difference between “on” and “off” states. (d) Fluorescence image of QD525 on NPG. (e) A 10ms trace of single QD525 fluorescence. (f) Box plot of single QD525 fluorescence intensity on NPG of various pore sizes. 20pM QD aqueous solution is used in the experiment.

We then conducted QD imaging on flat gold substrate without nanopores as a control. A much weaker fluorescent signal was detected because of a very weak fluorescence enhancement for QD525 and an obvious quench effect for QD605 by the non-porous substrate. This weak signal necessitated an increased exposure time of beyond 10’s milliseconds to image QDs but the resulting poor temporal resolution confounded observation of the blinking phenomenon for verifying the single dot events. This result demonstrates that the nanoporous structure of NPG plays a vital role for MEF that facilitates robust and quality imaging of single QDs.

In order to more quantitatively evaluate QD fluorescence enhancement by NPG, we deposited a relatively high concentration of QDs (2 nM) on NPG substrates and measured the ensemble fluorescence spectra. We verified through SEM energy disperse spectroscopy (EDS) that a similar number of QDs were deposited on the NPG substrates regardless of pore sizes (see Figure S2 in Supporting Information) and these QDs were uniformly distributed on NPG films (see Figure S3 in Supporting Information). A micro-Raman spectrometer (Renishaw InVia RM 1000) with an excitation laser wavelength of 514.5 nm was used for fluorescence spectra measurements, and the laser power was set at a low value of 0.3 mW with a laser spot of ~5 μm in diameter. As shown in Figure 4a and b, the fluorescence intensities of QDs on NPG were consistently higher than those on the flat gold substrate and glass slide. Ensemble fluorescence intensity is determined by the height of the 605 nm emission peak for QD605 and the 525 nm emission peak for QD525 in individual spectra. The fluorescence enhancement factor Ef(d), as a function of NPG pore size d, was calculated by dividing ensemble QD fluorescence intensity on the NPG with pore size d, FNPG(d), by ensemble QD fluorescence intensity on glass slide, Fglass:

Figure 4.

Fluorescence spectra of QD605 (a) and QD525 (b) on glass slide, flat gold and the NPG films. (c) and (d) show the QD605 and QD525 fluorescence enhancements by the NPG substrates, respectively, as a function of the pore sizes. The enhancement factors were determined as the ratio of the peak intensity of QDs on the NPG and the glass slide. (e) and (f) show the emission peak position of QD605 and QD525, respectively, on the NPG, non-porous gold substrate and glass slide. 2nM QD aqueous solution is used in the experiment.

Once again, we confirmed that the QD fluorescence enhancement factor is critically dependent on the NPG pore size d. The highest fluorescence enhancements of QD605 and QD525 were achieved from the 51 nm and 38 nm NPG substrates, respectively (Figure 4c and d), which is consistent with single QD imaging results (Figure 3). The maximum fluorescence enhancement factor of QD525 on the 38 nm NPG substrate is as high as ~100 fold, which, to our knowledge, is the highest reported so far. For QD605, the maximum fluorescence enhancement factor of ~50 fold was observed with the 50 nm NPG substrate.

Both results of single QD fluorescence imaging and ensemble fluorescence spectroscopy suggest that (1) there exists an optimum pore size at which the QD is best enhanced and that (2) the optimum NPG pore size is dependent on the QD species. The mechanism underlying these observations is unclear but is likely attributable to multiple factors. It is known that the spectrum of LSPR induced by NPG strongly depends on its pore size. When water is used as the dielectric medium, the peak excitation of NPG can shift from 500 nm to 650 nm as the pore size increases whereas the LSPR intensity decreases as the nanopore size increases. [31] This red-shifted excitation of NPG may be related to the shift of the optimum pore size from 38 nm for QD525 to 51 nm for QD605. To achieve the best MEF enhancement, the emission wavelength of QD525 and QD605 should be close to the LSPR peaks of NPG in order to enable optimal coupling. Also, compared with isolated gold nanoparticles, bicontinuous NPG, which is an ideally coupled system of localized and propagating surface plasmon polarizations (SPPs), can induce strongly enhanced local fields from the nearby ligaments and scatter efficiently without any loss of energy. The highly enhanced scattering fields can be absorbed by QDs, leading to highly amplified fluorescence. [10] Besides the double coupling effects, the QD extinction coefficient and hydrodynamic radius can also have a significant impact on overall fluorescence. In particular, since NPG has a 3D porous structure, a high level of enhancement also requires an appropriate geometric match between the QDs and nanopore channels. On the one hand, a stronger electromagnetic field is concentrated in smaller pores of the NPG, [25] hence contributing to a higher extinction coefficient of the QD within the pores. On the other hand, NPG with larger pores has a higher probability of accommodating QDs in the pores. The combination of the two mutually counteracting effects can also lead to an optimum pore size at which the QD fluorescence is best enhanced. Likewise, since the physical size of QD525 (~13 nm) is smaller than that of QD605 (~13 nm × 20 nm), it is reasonable that the optimum pore size for QD525 was smaller than the QD605 counterpart.

In this study we investigated the fluorescence enhancement of QDs by NPG using both single particle imaging and ensemble fluorescence spectroscopic approaches. Compared to non-porous gold substrates, NPG dramatically improves the signal intensity of single QDs. With ensemble fluorescence measurements, we observed 100-fold and 50-fold enhancements of fluorescence emitted from QD525 and QD605, respectively. Such high levels of enhancement are enabled by both the local surface plasmon resonance and propagating surface plasmon phenomena intrinsic to NPG substrates. In addition, we also observed a strong dependence of fluorescence enhancement on the characteristic pore size of NPG. QD525 and QD605 are best enhanced by the 38 nm and 51 nm NPG substrates, respectively. Furthermore, NPG permits comprehensive coupling between QDs and nanopore channels over a broad substrate area, offering a simple and robust material for both single particle and ensemble fluorescence applications.

Experimental section

Sample preparation

700 nm thick NPG films with various pore sizes were prepared by selective dissolution of silver from Ag65Au35 (at. %) alloy leaves using 71% nitric acid at room temperature for different time. [25, 26] After carefully washing with distilled water (18.2MΩcm), the as-prepared NPG films with an area of 2 mm × 2 mm were immersed in the QD solution for 1 hour, and then used for measurement after washing with distilled water. Materials and equipments: CdSe/ZnS core-shell nanocrystals, QD605 (peak emission at 605 nm) and QD525 (peak emission at 525 nm) that were conjugated with streptavidin were purchased from Invitrogen™. Microstructure characterization and QD quantification were performed by using a scanning electron microscope (SEM, JEOL JIB-4600F) and a transmission electron microscope (TEM, JEOL JEM-2100F). Zeiss LSM 510 Meta confocal microscope was used for single QD imaging, and a micro-Raman spectrometer (Renishaw InVia RM 1000) with incident wavelength of 514.5nm was used for ensemble QD fluorescence measurement.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Science Foundation (0967375, 1159771), National Institutes of Health (R01CA155305, R21CA173390, U54CA151838); “Global COE for Materials Research and Education”; “World Premier International Research Center (WPI) Initiative” by the MEXT; and, JST-CREST “Phase Interface Science for Highly Efficient Energy Utilization”, JST, Japan.

Footnotes

Supporting Information is available online from Wiley InterScience or from the author.

Contributor Information

Dr. Ling Zhang, WPI Advanced Institute for Materials Research, Tohoku University, Sendai 980-8577, Japan. Department of Mechanical Engineering, The Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD 21218, USA.

Dr. Yunke Song, Department of Biomedical Engineering, The Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD 21218, USA.

Dr. Takeshi Fujita, WPI Advanced Institute for Materials Research, Tohoku University, Sendai 980-8577, Japan

Ye Zhang, Department of Biomedical Engineering, The Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD 21218, USA.

Prof. Mingwei Chen, Email: mwchen@wpi-aimr.tohoku.ac.jp, WPI Advanced Institute for Materials Research, Tohoku University, Sendai 980-8577, Japan. Department of Mechanical Engineering, The Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD 21218, USA. CREST, Japan Science and Technology Agency (JST), Saitama 332-0012, Japan; State Key Laboratory of Metal Matrix Composites, School of Materials Science and Engineering, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Shanghai 200030, PR China

Prof. Tza-Huei Wang, Email: thwang@jhu.edu, Department of Mechanical Engineering, The Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD 21218, USA. Department of Biomedical Engineering, The Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD 21218, USA. Center of Cancer Nanotechnology Excellence, The Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD 21218, USA

References

- 1.Ming T, Chen H, Jiang R, Li Q, Wang J. J Phys Chem Lett. 2011;3:191. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Medintz IL, Tetsuo Uyeda H, Goldman ER, Mattoussi H. Nat Mater. 2005;4:435. doi: 10.1038/nmat1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mackowski S, Wo1rmke S, Maier AJ, Brotosudarmo THP, Harutyunyan H, Hartschuh A, Govorov AO, Scheer H, Bra1uchle C. Nano Lett. 2008;8:558. doi: 10.1021/nl072854o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kühn S, Håkanson U, Rogobete L, Sandoghdar V. Phy Rev Lett. 2006;97:017402. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.97.017402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Muskens OL, Giannini V, Sanchez-Gil JA, Gomez Rivas J. Nano Lett. 2007;7:2871. doi: 10.1021/nl0715847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang J, Fu Y, Chowdhury MH, Lakowicz JR. Nano Lett. 2007;7:2101. doi: 10.1021/nl071084d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zin MT, Leong K, Wong NY, Ma H, Sarikay M, Jen AKY. Nanotechnology. 2009;20:015305. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/20/1/015305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Akimov AV, Mukherjee A, Yu CL, Chang DE, Zibrov AS, Hemmer PR, Park H, Lukin MD. Nature. 2007;450:402. doi: 10.1038/nature06230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.LeBlanc SJ, McClanahan MR, Jones M, Moyer PJ. Nano Lett. 2013;13:1662. doi: 10.1021/nl400117h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Song JH, Atay T, Shi S, Urabe H, Nurmikko AV. Nano Lett. 2005;5:1557. doi: 10.1021/nl050813r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hwang E, Igor IS, Christopher CD. Nano Lett. 2010;10:813. doi: 10.1021/nl9031692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fu Y, Zhang J, Lakowicz JR. Chem Comm. 2009:313. doi: 10.1039/b816736b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alivisatos AP. Science. 1996;271:933. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chan WCW, Nie S. Science. 1998;281:2016. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5385.2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang CY, Yeh HC, Kuroki MT, Wang TH. Nat Mater. 2005;4:826. doi: 10.1038/nmat1508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ho YP, Kung MC, Yang S, Wang TH. Nano Lett. 2005;5:1693. doi: 10.1021/nl050888v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang Y, Wang TH. Theranostics. 2012;2(7):631. doi: 10.7150/thno.4308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Michalet X, Pinaud FF, Bentolila LA, Tsay JM, Doose S, Li JJ, Sundaresan G, Wu AM, Gambhir SS, Weiss S. Science. 2005;307:538. doi: 10.1126/science.1104274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gao X, Cui Y, Levenson RM, Chung LW, Nie S. Nat Biotechnol. 2004;22:969. doi: 10.1038/nbt994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kinkhabwala A, Yu Z, Fan S, Avlasevich Y, Müllen K, Moerner WE. Nat Photonics. 2009;3:654. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kuhn S, Hakanson U, Rogobete L, Sandoghdar V. Phys Rev Lett. 2006;97:017402. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.97.017402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bek A, Jansen R, Ringler M, Mayilo S, Klar TA, Feldmann J. Nano Lett. 2008;8:485. doi: 10.1021/nl072602n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lessard-Viger M, Rioux M, Rainville L, Boudreau D. Nano Lett. 2009;9:3066. doi: 10.1021/nl901553u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang J, Malicka J, Gryczynski I, Lakowicz JR. J Phys Chem B. 2005;109:7643. doi: 10.1021/jp0490103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lang XY, Guan PF, Zhang L, Fujita T, Chen MW. Appl Phys Lett. 2010;96:073701. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Qian LH, Yan XQ, Fujita T, Inoue A, Chen MW. Appl Phys Lett. 2007;90:153120. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Song YK, Zhang L, Chen MW, Wang T-H. IEEE-NANO; 2012; 12th IEEE conference. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alivisatos AP, Gu W, Larabell C. Annu Rev Biomed Eng. 2005;7:55. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.7.060804.100432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kulakovich O, Strekal N, Yaroshevich A, Maskevich S, Gaponenko S, Nabiev I, Woggon U, Artemyev M. Nano Lett. 2002;2:1449. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Acuna GP, Möller FM, Holzmeister P, Beater S, Lalkens B, Tinnefeld P. Science. 2012;338:506. doi: 10.1126/science.1228638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lang XY, Qian LH, Guan PF, Zi J, Chen MW. Appl Phys Lett. 2011;98:093701. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.