Abstract

Background

We evaluated the importance of measuring early vaginal levels of eight BV-associated bacteria, at two points in pregnancy, and the risk of spontaneous preterm delivery (SPTD) among pregnant women and the subgroup of pregnant women with a history of preterm delivery (PTD).

Methods

This prospective cohort study enrolled women at five urban obstetric practices at Temple University Hospital in Philadelphia PA. Women with singleton pregnancies less than 16 weeks gestation self-collected vaginal swabs at two points in pregnancy, prior to 16 weeks gestation and between 20-24 weeks gestation, to measure the presence and level of eight BV-associated bacteria. Women were followed-up for gestational age at delivery via medical records.

Results

Among women reporting a prior PTD, women with higher levels of Leptotrichia/Sneathia species, BVAB1 and Mobiluncus spp., prior to 16 weeks gestation, were significantly more likely to experience a SPTD. In addition, pregnant women with a prior PTD and increasing levels of Leptotrichia/Sneathia species (aOR: 9.1, 95% CI: 1.9-42.9), BVAB1 (aOR: 16.4, 95% CI: 4.3-62.7) or Megasphaera phylotype 1 (aOR: 6.2, 95% CI: 1.9-20.6), through 24 weeks gestation, were significantly more likely to experience a SPTD. Among the overall group of pregnant women, the levels of BV-associated bacteria were not related to SPTD.

Conclusion

Among the group of women reporting a prior PTD, increasing levels of BVAB1, Leptotrichia/Sneathia species, and Megasphaera phylotype 1, through mid-pregnancy were related to an increased risk of SPTD.

Keywords: BVAB1, Leptotrichia/Sneathia species, Megasphaera phylotype 1, preterm delivery

Preterm delivery (PTD), defined as a birth prior to 37 completed weeks gestation, affects more than 11.5% of all births and contributes to more than one-third of all infant deaths.1,2 Early markers to identify pregnant women at high risk for PTD and therapeutic efforts to reduce the risk of PTD have been limited.3 Prior PTD is the biggest predictor of subsequent PTD less than 37 weeks and the population attributable risk, the hypothetical reduction in the incidence of SPTD if prior PTD was eliminated, is 20% among Black women and 15% among non-Black women. 4,5 Bacterial vaginosis (BV) affects millions of women, is frequently chronic, and BV has been linked to numerous adverse pregnancy outcomes, including PTD. 6-9 Despite the consistently strong link between BV and PTD, many women with BV deliver at term, thus the identification of the specific BV associated bacteria linked to PTD and the examination of high risk subgroups of pregnant women at increased risk of PTD due to BV is needed.

In BV, there is a shift of vaginal microbiota from the normal abundance of Lactobacillus spp., primarily Lactobacillus crispatus and Lactobacillus iners, to the overgrowth of various gram negative and/or anaerobic bacteria, such as Gardnerella vaginalis, Atopobium spp., Megasphaera phylotype 1 spp., Mobiluncus spp., Ureaplasma urealyticum, Provetella, Peptostreptococcus, and Mycoplasma hominus. 10-11 This variability in lower genital tract microbiota among women with BV creates the potential for different impacts on risk of PTD.

Recent PCR-based strategies have been developed to identify and quantify hard to culture bacteria involved in complex microbial diseases by characterizing ribosomal RNA genes (rDNA).12,13 Using these PCR methods, both cultivated and uncultivated bacteria have been identified with the goal of determining their association with PTD. Recent studies have found that among women with symptoms of preterm labor, low levels of Lactobacillus, high concentrations of Gardnerella vaginalis, or a combination of high concentrations of Atopobium vaginae and Gardnerella vaginalis predict SPTD.14-17 The identification of other BV-associated bacteria concentrations earlier in pregnancy prior to signs of PTL, and among high risk subgroups such as women with a prior PTD, could dramatically improve the development of early prenatal screening methods with the ultimate goal of eliminating these bacteria to reduce PTD risk.

In this case-cohort assessment, drawn from a prospective pregnancy cohort study among urban women, we examined the independent role of vaginal Atopobium spp., Mobiluncus, Leptotrichia/Sneathia species, Megasphaera phylotype 1-like species, Gardnerella vaginalis and Bacterial Vaginosis-Associated Bacterium (BVAB) 1, 2 and 3 collected at two points in early pregnancy and the risk of SPTD.

Methods

ProjectBABIES enrolled pregnant women seen for their first prenatal care session at five urban obstetric practices at Temple University Hospital in Philadelphia PA from July 2008 through September 2011. Eligible women resided in the city of Philadelphia, reported a pregnancy less than 16 weeks gestation, and were English or Spanish speaking. Gestational age at enrollment was determined by self-reported last menstrual period and later confirmed by second trimester ultrasound with ultrasound evaluation considered the gold standard. Over 90% of women had an ultrasound and more than 85% of self-reported last menstrual period dates were within 2 weeks of the ultrasound reported last menstrual period date. Women were subsequently excluded from the study for the following reasons: multiple gestations, molar pregnancy, ectopic pregnancy, or the report of an elective abortion.

At enrollment, each woman self-collected two dry, foam vaginal swabs. Self-collected swabs have been shown to provide accurate and reliable results and excellent provider-agreement to measure BV and to quantify BV-associated bacteria. 18,19 The swab used to measure the BV-associated bacteria level was stored in a -80°C freezer and shipped, in batches, to the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center. Samples were subjected to DNA extraction with MoBio Ultra-clean soil DNA extraction method, following manufacturer directions. 12 Successful DNA extraction and the absence of PCR inhibitors were documented using a human 18S rRNA gene quantitative PCR assay, and an internal amplification control assay. 20 Eight real time quantitative PCR (qPCR) assays were run which targeted eight different BV-associated bacterial taxa: Leptotrichia/Sneathia species, Megasphaera phylotype 1-like species, Gardnerella vaginalis, Mobiluncus spp., Atopobium spp. and Bacterial Vaginosis-Associated Bacterium (BVAB) 1, BVAB2 and BVAB3. 12 This technique has been shown to be reproducible in other studies. These assays employ a TaqMan format in which species specific primers and probes are used to detect the amount of bacterial DNA from each taxonomic group. Known amounts of cloned bacterial 16S rDNA were added as standards in each qPCR in order to generate a standard curve and thus assess the amount of bacterial DNA in each vaginal sample. These assays all have a detection threshold of 1-10 16S rDNA molecules per reaction, and specificity such that the addition of one million copies of non-target vaginal bacterial 16S rDNA from 50 different vaginal bacterial species results in no detectable amplification. No-template PCR controls and sham digest DNA extraction controls were also run to monitor for bacterial contamination. The final BV-associated microbiota results were expressed as copies of microorganism DNA per swab.

At enrollment, the second self-collected swab was spread on a glass slide and transported, in batches, to the clinical microbiology lab at the University of Pennsylvania for gram staining and BV diagnosis using the Nugent criteria. 10 All slides were examined and interpreted by a single individual during the course of the study and reliability was previously confirmed. 18 Samples were graded to determine Nugent-score BV (score of 7-10), intermediate microflora (score of 4-6) or normal vaginal microflora (score of 0-3).

Enrolled women also completed a brief in-person baseline questionnaire to collect demographic information (i.e. age, marital status), prior obstetrical history (i.e. prior PTD, parity), and substance use (i.e. self-reported cocaine and cotinine use). Medical records were reviewed to confirm gestational age at enrollment, the inclusion and exclusion criteria, and gestational age at delivery. Estimates of gestational age at delivery were based on the ultrasound scan for the majority of the study participants (75%) who delivered at Temple University Hospital. For the remaining participants, birth certificate records were used to determine the date of delivery. This delivery date and the gestational age at enrollment from the ultrasound were used to calculate the gestational age at delivery. An ancillary validity study found excellent medical record reproducibility for pregnancy outcome information comparing two medical record abstractors. Preterm labor (PTL), preterm premature rupture of membranes (pPROM), first trimester cervical length, progesterone use, provider diagnosed BV, and BV treatment during the pregnancy were also abstracted from the labor and delivery or prenatal care medical record. This study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines established by Temple University Institutional Review Board and all women provided informed consent for all aspects of the study.

At the follow-up period, conducted between 20-24 weeks gestation, two additional swabs were self-collected and used to measure Nugent-defined BV and the same eight BV-associated bacterial taxa (Leptotrichia/Sneathia species, Megasphaera phylotype 1-like species, Gardnerella vaginalis, Mobiluncus spp., Atopobium spp. and Bacterial Vaginosis-Associated Bacterium (BVAB) 1, BVAB2 and BVAB3) during mid-pregnancy. We were able to re-contact and collect the follow-up swabs for 75% of the women enrolled at baseline.

Preterm delivery cases were classified via medical recorded review and classified as women delivering between 21.0 weeks and 36.6 completed week's gestation. Women delivering at 37 completed week's gestation or later were considered term control deliveries. PTD cases were further categorized as spontaneous preterm delivery (SPTD), defined as a non-medically indicated birth between 21.0 and 36.6 weeks gestation, or medically induced PTD due to maternal or fetal complications. Only the cases of SPTD were used for this assessment.

Statistical methods

We conducted a case-cohort analysis and examined the qPCR and Gram stain results for a 30% random sample of the entire pregnancy cohort and all of the SPTD cases, both inside and outside of the random cohort, as described by Prentice et al. 21 Given this design, all biologic samples and self-reported data were prospectively collected but the analyses compared the randomly generated term controls to all the SPTD cases. Enrolling women early in pregnancy in a prospective fashion ensured temporality and analyzing the results in a case-cohort fashion was valid, extremely cost effective, and allowed the calculation of relative risk of SPTD.

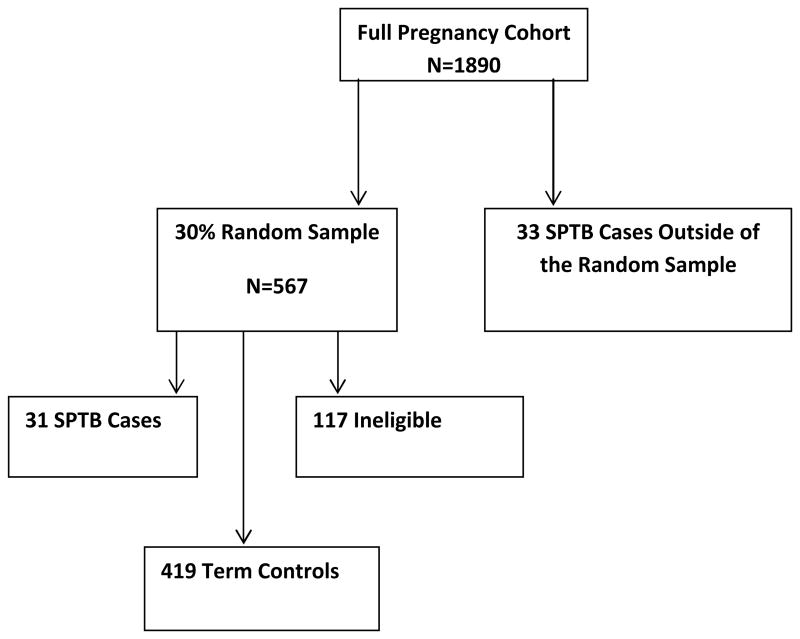

1890 eligible women were enrolled into the full pregnancy cohort, and using the case-cohort process, a randomly generated 30% sample set was identified to create the sub-cohort (N=567). 21, 22 After excluding subjects who were missing baseline qPCR values, subjects found to be ineligible after swab collection based on ultrasound gestational age confirmation, and women missing the follow-up swab, 31 SPTD cases and 419 term controls were included in the randomly selected sub-cohort (see Figure 1). An additional 33 SPTD cases were identified outside of the sub-cohort and, as outlined by Prentice et al, these cases were included in the final longitudinal dataset (N=483). We compared all the SPTD cases (N=64) to the randomly selected term controls (n=419).In theses analyses, weights were applied to reflect the sub-cohort membership and controls were weighted inversely proportional to the sampling fraction, which was 30%. All cases had a weight of 1 at the time of delivery and the 31 SPTD cases included in the randomly selected sub-cohort were initially considered controls until the gestational age that they became a case, at that gestational age, the weight changed to 1. 23

Figure 1.

Schematic of the randomly selected sub-cohort.

Initial assessment included a comparison of demographic information, reproductive factors, behavioral factors, BV and BV-associated bacteria concentrations between the SPTD cases and the term control group (Table 1 and Table 2). Student's t-tests were used to assess differences in mean estimates for continuous variables, and Chi-square or Fishers Exact tests were used to assess significant differences among categorical variables. For mean comparisons, the qPCR values were transformed to log base 10. The mean log base 10 concentration of each of the eight BV-associated bacteria were compared for the SPTD cases and term controls. For the continuous concentrations of each BV-associated bacteria, a negative or below the detectable threshold level was noted for values of 125, 250 or 500 gene copies per swab. For a more rigorous and conservative examination of mean differences, a value of 250 gene copies per swab was assigned as the non-detectable value instead of 0, qPCR values were further dichotomized according to detectable levels or not. Table 2 presents comparisons of continuous log mean concentrations, as well as percent positive values, using two sample t-tests. Spearman rank correlation coefficients were used to assess the bi-correlations between the BV-associated bacteria concentrations.

Table 1. Full sub-cohort.

Baseline Demographic/Reproductive History by Pregnancy Outcome

| SPTD Cases (n=64) |

Term Births (n=419) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic Information | |||

| Age (mean) | 23.5±6.0 | 22.6±5.1 | 0.18 |

| Pre-pregnancy BMI (mean) | 25.1±5.3 | 27.4±7.2 | 0.003 |

| African American | 44(68.8%) | 260(62.1%) | 0.33 |

| Hispanic | 7(10.9%) | 38(9.1%) | 0.82 |

| High School Graduate | 33(51.6%) | 242(57.8%) | 0.42 |

| Single | 55(85.9%) | 366(87.4%) | 0.69 |

| Current OB Information | |||

| Nulliparous | 27(42.2%) | 193(46.1%) | 0.59 |

| Nulligravid | 17(26.6%) | 144(34.4%) | 0.26 |

| Vaginal Bleeding | 9(14.1%) | 58(13.8%) | 0.99 |

| BV treatment any time in the pregnancy | 3(4.7%) | 13(3.1%) | 0.99 |

| PTL | 29(45.3%) | 11(2.6%) | <0.0001 |

| pPROM | 25(39.1%) | 1(0.2%) | <0.0001 |

| Gestational age in weeks (mean) | |||

| At enrollment | 9.4±3.9 | 10.4±3.6 | 0.06 |

| At delivery | 33.8±3.5 | 39.5±1.2 | <0.0001 |

| Prior OB Information | |||

| PTD | 15(23.4%) | 33(7.9%) | <0.0001 |

| Behavioral Information | |||

| Current Smoking | 14(21.9%) | 77(18.4%) | 0.49 |

| Current Cocaine Use | 1(1.6%) | 3(0.7%) | 0.44 |

| Current Stress | 5.8±3.4 | 5.2±3.4 | 0.18 |

| Douching in last month | 4(6.3%) | 19(4.5%) | 0.76 |

| Treated infections,current pregnancy | |||

| Bacterial Vaginosis | 3(4.7%) | 13(3.1%) | 0.99 |

| Chlamydia | 3(4.7%) | 14(3.3%) | 0.99 |

| Gonorrhea | 0(0.0%) | 2(0.5%) | 0.99 |

Table 2. Full sub-cohort.

Baseline BV, BV-associated Bacteria and Mean Concentration of Bacteria by Pregnancy Outcome

| SPTD Cases (n=64) |

Term Births (n=419) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nugent score at baseline | |||

| Bacterial vaginosis | 42(65.6%) | 306(73.0%) | 0.39 |

| Intermediate flora | 14(21.9%) | 65(15.5%) | |

| Normal flora | 4(6.3%) | 34(8.1%) | |

| BV-associated bacteria (percent positive) at baseline | |||

| Leptotrichia/Sneathia species | 44(68.8%) | 289(69.0%) | 0.99 |

| BVAB1 | 34(53.1%) | 216(51.6%) | 0.89 |

| BVAB2 | 37(57.8%) | 260(62.1%) | 0.58 |

| BVAB3 | 25(39.1%) | 182(43.4%) | 0.59 |

| Megasphaera phylotype 1 | 44(68.8%) | 292(69.7%) | 0.89 |

| Atopobium spp. | 50(78.1%) | 346(82.6%) | 0.39 |

| Gardnerella vaginalis | 59(92.2%) | 394(94.0%) | 0.58 |

| Mobiluncus spp. | 38(59.4%) | 250(59.7%) | 0.99 |

| BV-associated bacteria at baseline (log mean concentration) | |||

| Leptotrichia/Sneathia species | 5.1±2.3 | 5.2±2.3 | 0.70 |

| BVAB1 | 4.9±3.1 | 4.8±3.0 | 0.82 |

| BVAB2 | 4.6±2.1 | 4.6±2.0 | 0.96 |

| BVAB3 | 3.3±1.5 | 3.6±1.6 | 0.19 |

| Megasphaera phylotype 1 | 5.8±2.7 | 5.7±2.6 | 0.69 |

| Atopobium spp. | 5.7±2.3 | 5.7±2.2 | 0.95 |

| Gardnerella vaginalis | 6.8±2.2 | 7.0±2.0 | 0.61 |

| Mobiluncus spp. | 3.6±1.5 | 3.6±1.3 | 0.91 |

PHREG for repeated measures was used to examine the role of increasing levels of BV-associated bacteria from prior to 16 weeks through 24 weeks gestation and risk of SPTD. Each model included: the baseline (t1) log level (collected prior to 16 weeks gestation), the change in each bacteria level from baseline (t1) to follow-up period (t2), and pre-pregnancy BMI. Given the significant role of low pre-pregnancy BMI found in this and other studies, this covariate was added to the model. 5 The change in bacteria level was identified using a created variable which compared the baseline (t1) level and the follow-up (t2) level, the change variable was set to 0 if the t1 and t2 values remained the same or if the t2 level decreased compared to the t1 level. If the change from t1 to t2 was an increase, the change was set to 1 (yes). All analyses were also stratified by prior PTD (yes/no).

SAS version 9.3 was used for all analyses. A 2-sided p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

The sample included primarily low income, unmarried, young, African American women with limited education. No demographic factors differed between the two groups. (Table1). The SPTD group reported a significantly lower pre-pregnancy BMI compared to the term control group (25.1 vs. 27.4, p=0.003) and as expected, the SPTD group was more likely to experience preterm labor (PTL) and preterm premature rupture of membrane (pPROM) during the pregnancy as documented in the medical record (45.3% vs. 2.61%, p<0.0001 and 39.1% vs. 0.2%, p<0.0001; respectively) (Table 1). The proportion of women reporting a prior PTD was also significantly higher in the SPTD group (23.4% vs. 7.9 %, p<0.001). The SPTD group provided the baseline vaginal sample at a slightly earlier gestation age compared to the term control group (9.4 + 3.9 vs. 10.4 + 3.6 weeks; p<0.06). Self-reported cocaine use, cigarette use and stress during the pregnancy were similar between the two groups (Table 1). The diagnosis and treatment of lower genital tract infections, including symptomatic BV, during the current pregnancy were also similar between the SPTD and term control groups, these results were similar when stratified by prior PTD. The prevalence of progesterone therapy and cervical length shorter than 25 mm was similar between the two groups (data not shown).

In this urban population of young, primarily African American pregnant women, the prevalence of Nugent-defined BV early in pregnancy was over 65%; however, Nugent-defined BV was not related to the risk of SPTD (p=0.39)(Table 2). The prevalence of each of the BV-associated bacteria was high in both groups and the most prevalent bacteria prior to 16 weeks gestation was Atopobium spp. and Gardnerella vaginalis. In the overall group of pregnant women, the levels of BV-associated bacteria were not related to STPB. Among the group of pregnant women reporting a prior PTD, the presence of Leptotrichia/Sneathia species, BVAB1 or Mobiluncus spp, prior to 16 weeks gestation, was predictive of a SPTD (86.7% vs. 48.5%, p=0.02, 80.0% vs. 45.5%, p=0.03, and 86.7% vs. 51.5%, p=0.03 respectively)(Table 2a). In addition, the mean level of Leptotrichia/Sneathia species, BVAB1, BVAB2, Atopobium spp. and Gardnerella vaginalis, at baseline, was significantly higher among the women experiencing a SPTD who reported a prior PTD compared to the term group (Table 2a). We did not find an interaction between the presence of any of the BV-associated bacteria at baseline and the risk of SPTB. Among women without a history of PTD, there were no significant differences in the proportion of women positive for any of the BV-associated bacteria at baseline, the mean level of the BV-associated bacteria at baseline, or the Nugent-BV scores comparing the two groups (data not shown).

Table 2a. Women with prior PTD.

Baseline BV, BV-associated bacteria and Mean Concentration of Bacteria by Pregnancy Outcome

| SPTD Cases (n=15) |

Term Births (n=33) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nugent score at baseline | |||

| Bacterial vaginosis | 9(60.0%) | 19(57.6%) | 0.74 |

| Intermediate flora | 4(26.7%) | 7(21.2%) | |

| Normal flora | 1(6.7%) | 6(18.2%) | |

| BV-associated bacteria (percent positive) at basline | |||

| Leptotrichia/Sneathia species | 13(86.7%) | 16(48.5%) | 0.02 |

| BVAB1 | 12(80.0%) | 15(45.5%) | 0.03 |

| BVAB2 | 11(73.3%) | 15(45.5%) | 0.12 |

| BVAB3 | 7(46.7%) | 9(27.3%) | 0.21 |

| Megasphaera phylotype 1 | 12(80.0%) | 19(57.6%) | 0.19 |

| Atopobium spp. | 14(93.3%) | 23(69.7%) | 0.14 |

| Gardnerella vaginalis | 15(100.0%) | 28(84.9%) | 0.17 |

| Mobiluncus spp. | 13(86.7%) | 17(51.5%) | 0.03 |

| BV-associated bacteria at baseline (log mean concentration) | |||

| Leptotrichia/Sneathia species | 5.8±1.9 | 4.2±2.3 | 0.03 |

| BVAB1 | 6.4±2.8 | 4.4±2.8 | 0.03 |

| BVAB2 | 5.2±1.9 | 3.8±2.0 | 0.03 |

| BVAB3 | 3.4±1.5 | 3.3±1.6 | 0.74 |

| Megasphaera phylotype 1 | 6.1±2.4 | 4.7±2.5 | 0.08 |

| Atopobium spp. | 6.3±1.9 | 4.6±2.3 | 0.02 |

| Gardnerella vaginalis | 7.4±1.7 | 6.0±2.4 | 0.05 |

| Mobiluncus spp. | 4.1±1.6 | 3.3±1.3 | 0.05 |

Results from the PHREG models which adjusted for pre-pregnancy BMI and the baseline BV-associated bacteria levels further indicated that increasing levels of Leptotrichia/Sneathia species, BVAB1 or Megasphaera phylotype 1 through mid-pregnancy increased the risk of SPTD among the sub-group of women with a prior PTD. As shown in Table 3, women reporting a prior PTD found to have increasing levels of Leptotrichia/Sneathia species through mid-pregnancy were nine times more likely to experience a SPTD (aHR: 9.19, 95% CI: 1.93-42.95) and women reporting a prior PTD with increasing levels of BVAB1 through mid-pregnancy were sixteen times more likely to experience a SPTD (aHR: 16.41, 95%CI: 4.33-62.67)(Table 3). In addition, increasing levels of Megasphaera phylotype 1 through mid-pregnancy significantly increased the risk of a SPTD (aHR: 6.28, 95% CI: 1.87-20.58) among the sub-group of women with a prior PTD. We found regardless of the level of Leptotrichia/Sneathia species, BVAB1 or Megasphaera phylotype 1 at baseline, an increase in these bacteria through mid-pregnancy significantly increased the risk of SPTB. Among the subset of women without a prior PTD, increasing levels of Leptotrichia/Sneathia species through mid-pregnancy slightly increased the risk of SPTD (aHR: 1.94, 94%CI: 1.00-3.59) although this relationship was marginal (Table 3).

Table 3.

Hazard Ratios for Increase in BV-associated Microbiota* and Risk of PTD

| Full sub-cohort | aHazard Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|

| Leptotrichia/Sneathia species | 1.8 | 1.0-3.0 |

| BVAB1 | 1.8 | 1.0– 3.1 |

| BVAB2 | 1.3 | 0.7-2.3 |

| BVAB3 | 1.6 | 0.7-3.1 |

| Megasphaera phylotype 1 | 1.4 | 0.8-2.3 |

| Atopobium spp. | 1.1 | 0.6 - 1.8 |

| Gardnerella vaginalis | 1.47 | 0.9-2.4 |

| Mobiluncus spp. | 1.6 | 0.9-2.7 |

| Subgroup of women with a Prior PTD | ||

| Leptotrichia/Sneathia species | 9.2 | 1.9-42.9 |

| BVAB1 | 16.4 | 4.3-62.7 |

| BVAB2 | 0.7 | 0.2-2.2 |

| BVAB3 | 2.3 | 0.3-11.8 |

| Megasphaera phylotype 1 | 6.3 | 1.9-20.6 |

| Atopobium spp. | 1.4 | 0.4– 4.2 |

| Gardnerella vaginalis | 2.2 | 0.7-6.4 |

| Mobiluncus spp. | 2.5 | 0.6-8.6 |

| Subgroup of women with no prior PTD | ||

| Leptotrichia/Sneathia species | 1.9 | 1.0- 3.6 |

| BVAB1 | 1.6 | 0.8- 2.9 |

| BVAB2 | 1.4 | 0.7-2.6 |

| BVAB3 | 1.7 | 0.7-3.6 |

| Megasphaera phylotype 1 | 1.3 | 0.7- 2.3 |

| Atopobium spp. | 1.1 | 0.6-2.1 |

| Gardnerella vaginalis | 1.5 | 0.8-2.7 |

| Mobiluncus spp. | 1.7 | 0.9- 3.1 |

Hazard ratios are associated with dichotomous indicator variable representing an increase in microbiota from T1 from T2; each was adjusted for baseline (T1) microbiota level measured on a continuum and BMI.

Comments

There are very few first trimester predictors of SPTD and limited, identified modifiable risk factors. As reported here and by others, one of the strongest consistent predictors of SPTD is a prior history of PTD 24, 25 We found that among women reporting a prior PTD, women experiencing a SPTD in the current pregnancy were nine times more likely to have increasing levels of Leptotrichia/Sneathia, and six times more likely to have increasing levels of Megasphaera phylotype 1 through mid-pregnancy. The role of BVAB1 was even greater with a 16 fold increased risk of STPB among women with a prior PTD who experienced increasing levels of BVAB1 through 24 weeks gestation. This is one of the first studies to examine numerous BV-associated bacteria early in pregnancy and the first large study to indicate a role of early and increasing levels of Leptotrichia/Sneathia, BVAB1or Megasphaera phylotype 1 and STPB risk among a subset of high risk pregnant women.

These BV-associated bacteria have been shown to promote an inflammatory response, through heightened cytokine and chemokine production in the lower genital tract, and this heightened inflammation may influence gestational length. 26,27 It is clear that lower genital tract bacteria can ascend to the upper genital tract and invade the choriodecidual space, amnion and chorion promoting further inflammation through cytokine and chemokine release. 26 Among studies of PTD development, heightened prostaglandins stimulate uterine contractions and metalloproteases attack the chorioamniotic membranes leading to premature rupture of the membranes and softening of the collagen in the cervix. Increased prostaglandin and endotoxins may cause uterine inflammation promoting mucinases and sialidase production allowing the ascension of lower genital tract microorganisms, including BV-associated bacteria, to the upper genital tract. 15, 28 Cauci et al found that high sialidase levels at 28-36 weeks gestation were linked to an increase in PTD among women with BV and Han et al reported that women positive for Leptotrichia/Sneathia in amniotic fluid had increased Interleukin-6 levels indicating the role of bacteria in upper genital track inflammation. 29,30 Our findings add evidence to the role of BV-associated bacteria, early in pregnancy and throughout mid-pregnancy, increasing the risk of STPD through excessive lower and upper track inflammation.

These results also suggest that a select group of pregnant women may be hyper-responsive to high levels of BV-associated bacteria during pregnancy due to their genetic susceptibility and/or their prior and current pregnancy history. We previously reported that among young, urban pregnant women presenting with PTL, high levels of Megasphaera phylotype 1 increased the risk of SPTB15. Others have reported that the combination of high levels of Gardnerella vaginalis and Atopobium spp among women presenting with symptoms of PTL were related to an increased risk of SPTD. 14 In addition, Macones et al. and others found a positive interaction between the rare allele of the tumor necrosis factor alpha gene (TNF2-carrier), symptomatic Nugent-defined BV and an increased risk of SPTB. 31-33

In this study, we found over 65% of women were positive for Nugent-defined BV, which is similar to the high rate of BV among urban populations of pregnant women. 29,34 Given the high prevalence of BV among urban women, many women may have pre-pregnancy microflora consistent with Nugent-defined BV or high pre-pregnancy levels of BV-associated bacteria. The chronic nature of Nugent-defined BV has been reported by others and high levels of Leptotrichia/Sneathia species, BVAB1 or Megasphaera phylotype 1 during reproductive life, through the inter-pregnancy interval and across several pregnancies is possible. This chronicity may explain our findings that high levels of Leptotrichia/Sneathia species, BVAB1 or Megasphaera phylotype 1, among the subset of women with a history of PTD, increased the risk of STPD. We do recognize that chronically high levels of BV-associated bacteria may also be related to prior PTD risk, thus restricting our assessment to the group of women with a history of PTD may introduce collider bias 35 This collider bias would primarily occur if persistently high levels of BV-associated bacteria were also related to prior PTD risk although other unmeasured confounders cannot be ruled out. We did attempt to determine the proportion of women reporting a prior PTD who also reported a previous BV diagnosis or prior BV treatment. We found an equal proportion of self-reported prior BV among women with and without a prior PTD (28% and 27%, respectively). In the future, understanding persistent SPTD risk across multiple pregnancies among women with chronically high levels of BV-associated bacteria will assess the role of collider bias and determine the importance of chronically high levels of BV-associated bacteria across multiple pregnancies.

Several limitations need to be recognized when interpreting these results. First, we only assessed a select, fairly prevalent group of BV-associated bacteria. In particular, we did not examine the role of high concentrations of Ureaplasma urealyticum, Prevotella, Peptostreptococcus species or low concentrations of Lactobacillus crispatus or Lactobacillus iners early in pregnancy and risk of SPTD. The future examination of Lactobacillus crispatus and Lactobacillus iners will be particularly interesting given the protective influence of Lactobacillus in BV development and the lack of effective BV treatment options to promote long-term reconstitution of high levels of Lactobacillus. 36 Second, we had a very high prevalence of BV among this pregnancy cohort which may restrict the generalizability of the study results. In addition, others have reported differences in the composition of BV-associated vaginal microbiota by racial/ethnic groups. This study included primarily African American, urban women which should be recognized when interpreting these findings.27,37 Third, we did not measure the proposed consequences of high levels of BV-associated bacteria in the lower genital tract by examining lower genital tract chemokine, cytokine or sialidase levels. Fourth, given the small number of women with consistently high levels through mid-pregnancy we were unable to evaluate the role of consistently high levels and STPB risk. Finally, the analysis restricted to women with a prior history of PTD resulted in a limited number of cases of SPTD, thus caution is warranted when interpreting these findings.

Given the adverse neonatal, economic and public health impact of high rates of infant morbidity and mortality due to SPTD, this study attempts to identify a group of women, early in pregnancy, at the highest risk of SPTD based on early pregnancy concentrations of selected BV-associated bacteria. We found that among the subgroup of women reporting a prior PTD, high level of Leptotrichia/Sneathia species, BVAB1 or Mobiluncus spp prior to 16 weeks gestation and increasing levels of Leptotrichia Sneathia species, BVAB1 or Megasphaera-like phylotype 1 through mid-pregnancy were related to an increased risk of STPB. Continued examination of the role of consistently high levels of these bacteria throughout pregnancy, and the role of other BV-associated bacteria among high risk subgroups are warranted to inform interventions to reduce SPTD among the highest risk group of pregnant women.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge and thank Jill Wadlin at the University of Pennsylvania for laboratory technical assistance, the nurses and nurse managers at Temple University hospital, Jennifer Sears and the Philadelphia Department of Public Health.

Funding: This work was supported by funding from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R01HD038856)

Footnotes

Disclosure: None of the authors report any conflict of interest

References

- 1.Goldenberg Rl, Culhane JF, Iams JD, Romero R. Epidemiology and causes of preterm Birth. Lancet. 2008;371:75–84. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60074-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hamilton BE, Martin JA, Ventura SJ. Births: Preliminary Data for 2012. National Vital Statistics Reports. 2013;62(3) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goldenberg RI, Simcox R, Sin WT, Seed PT, Briley A, Shennan AH. Prophylactic Antibiotics for the Prevention of Preterm Birth In Women At Risk: A Meta-Analysis. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2007;47(5):368–77f. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-828X.2007.00759.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Iams JD, Goldenberg RL, Mercer BM, Moawad A, Thom E, et al. The Preterm Prediction Study: Recurrence risk of spontaneous preterm birth. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1998;178:1035–40. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(98)70544-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goldenberg RL, Iams JD, Mercer BM, Meis PJ, Moawad A, et al. The Preterm Prediction Study: The value of New vs. Standard Risk Factors in Predicting Early and All Spontaneous Preterm Births. American Journal of Public Health. 1998;88:233–238. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.2.233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hillier SL, Nugent RP, Eschenbach DA, Krohn MA, Gibbs RS, Martin DH, et al. Association Between Bacterial Vaginosis And Preterm Delivery Of A Low-Birth-Weight Infant. New England Journal of Medicine. 1995;333:1737–1742. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199512283332604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hay PE, Lamont RF, Taylor-Robinson D, Morgan DJ, Ison C, Pearson J. Abnormal Bacterial Colonization Of The Genital Tract And Subsequent Preterm Delivery And Late Miscarriage. British Medical Journal. 1994;308(6924):295–98. doi: 10.1136/bmj.308.6924.295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meis PJ, Goldenberg RL, Mercer B, et al. The Preterm Prediction Study: Significance Of Vaginal Infections. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1995;173:1231–1235. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(95)91360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leitich H, Bodner BA, Brunbauer M, et al. Bacterial Vaginosis as a Risk Factor for Preterm Delivery: A Meta-Analysis. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2003;189:139–147. doi: 10.1067/mob.2003.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nugent RP, Krohn MA, Hillier SL. Reliability Of Diagnosing Bacterial Vaginosis Is Improved By A Standardized Method Of Gram Stain Interpretation. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 1991;29:297–301. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.2.297-301.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beigi RH, Wiesenfeld HC, Hillier SL, Straw T, Krohn MA. Factors Associated With Absence Of H2O2-Producing Lactobacillus Among Women With Bacterial Vaginosis. Journal of Infectious Disease. 2005;11(6):924–9. doi: 10.1086/428288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fredricks DN, Fiedler TL, Marrazzo JM. Molecular Identification of Bacteria Associated with Bacterial Vaginosis. New England Journal of Medicine. 2005;353(18):1899–1911. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cartwright CP, Lembke BD, Ramachandran K, Body BA, Nye MB, Rivers CA, Schwebke JR. Development and Validation of a Semiquantitative, Multitarget PCR Assay for Diagnosis of Bacterial Vaginosis. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2012;50(7):2321–2329. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00506-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Menard JP, mazouni C, Salem-Cherif I, Fenollar F, Raoult D, Boubli L, Gamerre M, Bretelle F. High Vaginal Concentrations of Atopobium vaginae and Gardnerella vaginalis in women undergoing preterm labor. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2010;115(1):134–140. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181c391d7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nelson DB, Hanlon A, Hassan S, Britto J, Geifman-Holtzman O, Haggery C, Fredricks DN. Preterm labor and bacterial vaginosis-associated bacteria among urban women. Journal of Perinatal Medical Association. 2009;37:130–134. doi: 10.1515/JPM.2009.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.DiGiulio DB, Romero R, Kusanovic JP, Gomez R, Kim CJ, et al. Prevalence and diversity of microbes in the amniotic fluid, the fetal inflammatory response, and pregnancy outcome in women with preterm pre-labor rupture of membranes. American Journal of Reproductive Immunology. 2010;64:38–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2010.00830.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wilks M, Wiggins R, Shiley A, Hennessy E, Warwick S, Porter H, Corfield A, Millar M. Identification of H(2)O(2) production of vaginal lactobacilli from pregnant women at high risk of preterm birth and relation with outcome. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2004;42(2):713–7. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.2.713-717.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nelson DB, Bellamy S, Gray TS, Nachamkin I. Self-Collected vs. Provider-Collected Vaginal Swabs for the Diagnosis of Bacterial Vaginosis: An Assessment of Validity and Reliability. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2003;56:862–866. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(03)00073-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Menard JP, Fenollar F, Raoult D, Boubli L, Bretelle F. Self-collected vaginal swabs for the quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction assay of Atopobium vaginae and Gardnerella vaginalis and the diagnosis of bacterial Vaginosis. European Journal of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Disease. 2012;31:513–518. doi: 10.1007/s10096-011-1341-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fredricks DN, Fiedler TL, Thomas KK, Oakley BB, Marrazzo JM. Targeted PCR for Detection of Vaginal Bacteria Associated with Bacterial Vaginosis. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2007;45(10):3270–3276. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01272-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Prentice RL. A Case Cohort Design for Epidemiologic Cohort Studies and Disease Prevention Trials. Biometrika. 1986;73(1):1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barlow WE, Ichikawa L, Rosner D, Izumi S. Analysis of Case-Cohort Designs. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 1999;52(12):1165–1172. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(99)00102-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barlow WE, Ichikawa L, Rosner D, Izumi S. Robust Variance Estimantion for the Case-Cohort Design. Biometrics. 1994;50(4):1064–1072. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goldenberg RL, Mayberry SK, Copper RL, DuBard MB, Hauth JC. Pregnancy outcome following a second-trimester loss. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1993;81:444–446. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mercer BM, Goldenberg RL, Moawad AH, et al. The Preterm Prediction Study: effect of gestational age and cause of preterm birth on subsequent obstetric outcome. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1999;181:1216–1221. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(99)70111-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goldenberg RL, Hauth JC, Andrews WW. Intrauterine Infection and Preterm Delivery. New England Journal of Medicine. 2000;342(20):1500–1507. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200005183422007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hedges SR, Barrientes F, Desmond RA, Schwebke JR. Local And Systemic Cytokine Levels In Relation To Changes In Vaginal Flora. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2006;193(4):556–62. doi: 10.1086/499824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gravett MG, Hummel D, Eschenbach DA, Holmes KK. Preterm Labor Associated with Subclinical Amniotic Fluid Infection and With Bacterial Vaginosis. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1986;67:29–237. doi: 10.1097/00006250-198602000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cauci S, Culhane JF. High sialidase levels increase preterm birth risk among women who are Bacterial Vaginosis positive in early gestation. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2011;204(2):142.e1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.08.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Han YW, Shen T, Chung P, Buhimschi IA, Buhimschi CS. Uncultivated bacteria as etiologic agents of intra-amniotic inflammation leading to preterm birth. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2009;47(1):38–47. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01206-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Macones G. A polymorphism in the promoter region of TNF and bacterial vaginosis: preliminary evidence of gene-environment interaction in the etiology of spontaneous preterm birth. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2004;190(6):1504–1508. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Romero, et al. Bacterial vaginosis, the inflammatory response and the risk of preterm birth: a role for genetic epidemiology in the prevention of preterm birth. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2004;190(6):1509–1519. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jones, et al. Interplay of cytokine polymorphisms and bacterial vaginosis in the etiology of preterm delivery. Journal of Reproductive Immunology. 2010;87(1):82–89. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2010.06.158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gomez LM, Sammel MD, Appleby DH, Elovitz MA, Baldwin DA, Jeffcoat MK, Macones GA, Parry S. Evidence of a gene-environment interaction that predisposes to spontaneous preterm birth: a role for asymptomatic bacterial vaginosis and DNA variants in genes that control the inflammatory response. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2010;202:386.e1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.01.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wilcox AJ, Weinberg CR, Basso O. On the pitfalls of adjusting for gestational age at birth. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2011;174(9):1062–1068. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Leitich H, Bodner-Adler B, Brunbauer M, Kaider A, Egarter C, Husslein P. Bacterial vaginosis as a risk factor for preterm delivery: a meta-analysis. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2007;21:375–90. doi: 10.1067/mob.2003.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Harper LM, Parry S, Stamilio DM, Odibo AO, Cahill AG, Strauss JF, 3rd, Macones GA. The interaction effect of Bacterial Vaginosis and Periodontal Disease on the risk of preterm birth. American Journal of Perinatalogy. 2012;29(5):347–52. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1295644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]