Abstract

Objectives. Because only a fraction of patients with acute viral hepatitis A, B, and C are reported through national surveillance to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, we estimated the true numbers.

Methods. We applied a simple probabilistic model to estimate the fraction of patients with acute hepatitis A, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C who would have been symptomatic, would have sought health care tests, and would have been reported to health officials in 2011.

Results. For hepatitis A, the frequencies of symptoms (85%), care seeking (88%), and reporting (69%) yielded an estimate of 2730 infections (2.0 infections per reported case). For hepatitis B, the frequencies of symptoms (39%), care seeking (88%), and reporting (45%) indicated 18 730 infections (6.5 infections per reported case). For hepatitis C, the frequency of symptoms among injection drug users (13%) and those infected otherwise (48%), proportion seeking care (88%), and percentage reported (53%) indicated 17 100 infections (12.3 infections per reported case).

Conclusions. These adjustment factors will allow state and local health authorities to estimate acute hepatitis infections locally and plan prevention activities accordingly.

Infection with hepatitis A, B, and C (HAV, HBV, and HCV, respectively) remains a substantial health problem in the United States.1–3 Chronic HBV4 and HCV5 infections currently affect more than 4 million US residents and now account for more deaths than does HIV/AIDS.6 New HAV and HBV infections have been prevented by the adoption of universal infant vaccination in the United States, but acute infections continue to occur and cause substantial morbidity and mortality.7 Monitoring case patients with acute HAV, HBV, and HCV is important for several reasons. Identifying individuals with acute infections serves to describe modes of transmission and to detect and control outbreaks. Furthermore, prevention interventions of various types—for example, vaccinating susceptible persons, getting injection drug users into treatment programs, treating persons who are chronically infected to prevent secondary transmission, and preventing complications—require ongoing surveillance and analysis of individuals with acute infections of these 3 viruses.

Only a fraction of individuals with acute infections of these 3 viruses are reported eventually to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in the United States. Barriers to ascertaining and reporting hepatitis infections are many, often reflecting the ability of and resources allotted to the local and state health jurisdictions monitoring them. Natural barriers include the following: most individuals with acute infections of any of the 3 viruses are asymptomatic, only some of those with symptoms seek medical care and testing, and even of those diagnosed, some fraction is not reported or enumerated. Complete reporting of, at a minimum, symptomatic case patients is essential because only by identifying them can interventions be implemented to limit disease in the community. Outbreaks are most often detected from the identification of symptomatic case patients.

Currently, the CDC estimates incident HAV, HBV, and HCV infections using reports of case patients to develop adjustments through 3 simple probabilistic multiplier models; however, the methods used to develop the estimating factors (multipliers) are outdated and have never been well described or publicly available. Thus, our goal was to update estimates of the number of individuals with acute infections using 2011 reports of case patients.

METHODS

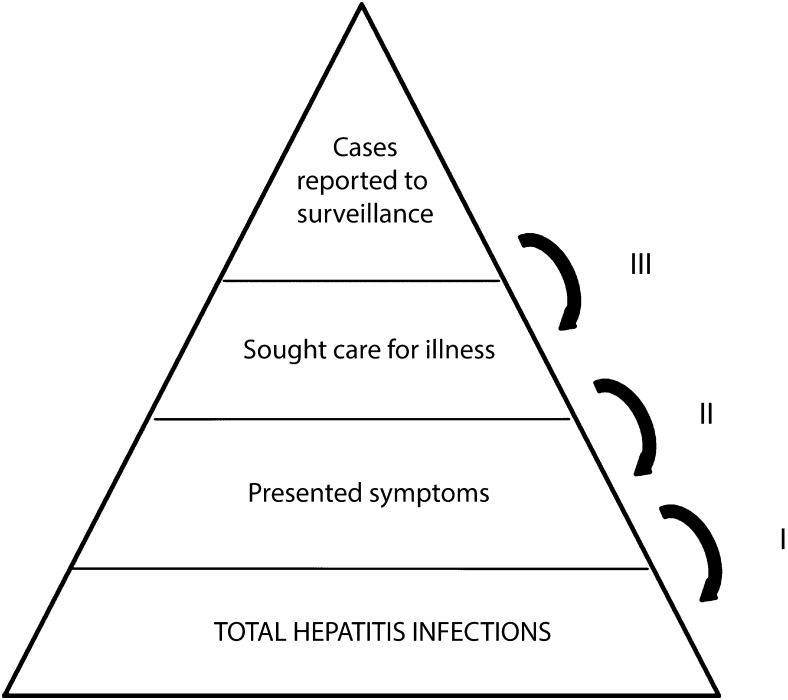

We adapted a model used previously to estimate the number of those infected with pandemic influenza in 2009. That model is relevant because hepatitis and influenza virus infections have similar surveillance challenges, including the following: many infected individuals are asymptomatic, not all ill persons seek care, specimens sometimes yield false results, and not all true case patients are reported to health departments.8 Our model used a simple multiplier approach requiring 3 parameters: (1) the proportion of infected persons developing symptoms, (2) the proportion of those who sought care, and (3) the proportion of those diagnosed who were reported to hepatitis surveillance (Figure 1). We obtained these parameter proportions from a literature search. We included the proportion from each of the studies in a random effects model, resulting in a pooled proportion.9 Then, we multiplied the inverse of the pooled proportions by the number of case patients reported to the National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System (NNDSS)7 to derive the final estimates.

FIGURE 1—

Steps used to estimate new infections of viral hepatitis among adults: United States, 2011.

Study Selection and Data Extraction

We searched PubMed for studies of acute HAV, HBV, or HCV using combinations of the following medical subject headings terms: “hepatitis virus,” “disease outbreaks,” “human hepatitis A virus,” “hepatitis B,” “acute hepatitis C,” and “United States.” We then abstracted the number of individuals with acute infections identified and the proportion exhibiting signs or symptoms.

In addition, we searched among outbreak investigations for which adequate records allowed the calculation of symptomatic case patients among acutely infected persons. We obtained these from records of the health care transmission of hepatitis since 1989 and published online.10

Inclusion Criteria

We included studies of US adult populations that were published in English from 1980 through October 2012. We included only studies that used serology to define new infections. Some studies used signs and symptoms as their case definition, and we did not include those reports.

None of the studies described the frequency with which persons with viral hepatitis symptoms sought care. Instead, we used data from the 2010 National Health Interview Survey.11 Briefly, the National Health Interview Survey uses a probability sampling of US households. The questions we analyzed were asked of adults aged 18 years or older: “Is there a place that you usually go to when you are sick or need advice about your health?” and “Have you ever had hepatitis?” We calculated the prevalence of responding yes to both questions: a person with hepatitis infection reporting a routine source of care.

Source of Reported Case Patients

In the United States, symptomatic case patients with acute hepatitis infections are reported to the NNDSS. State and territorial health departments send reports voluntarily every week. Case patient definitions for acute HAV, HBV, and HCV are established in collaboration with the Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists and require a combination of clinical and laboratory criteria. Definitions are available online.12

We used data reported to the NNDSS in 2011 to identify the number of case patients reported for the multiplier approach.7 For HCV only, we estimated the number of reported individuals who may have been infected by injection drug use13 because 78% of case patients with acute HCV reported to NNDSS have missing or no information on mode of transmission.7

RESULTS

Our literature search identified 226 studies published since 1980. Of these, 39 met our inclusion criteria (Table 1). Of the outbreak investigations, most were captured in the literature review; only 1 that had measured the frequency with which infected persons presented signs or symptoms had not been published in a peer-reviewed journal.51 There were 6 studies of HAV, 15 of HBV, and 13 of HCV that described the proportion of infections with signs or symptoms of hepatitis. Even fewer studies measured underreporting of symptomatic infections to surveillance; we found 2 for HAV and 3 each for HBV and HCV.

TABLE 1—

Model Parameters and Sources of Data Used to Adjust Number of Case Participants Reported to Surveillance for Estimating Incident Viral Hepatitis Infections: United States, 2011

| Parameter/Setting | Year | Location and Reference | No./Total (%) | Pooled Estimate, % |

| Hepatitis A | ||||

| Frequency of symptoms | 84.8 | |||

| Restaurant staff | 2003 | Pennsylvania14 | 13/13 (100) | |

| Health department | 2005 | Connecticut15 | 108/127 (85) | |

| Health department | 2005 | Alaska15 | 27/37 (73) | |

| Sentinel Counties Study of Viral Hepatitis | 2005 | US counties15 | 53/140 (38) | |

| Military field training | 1982 | US military base, Germany16 | 28/29 (97) | |

| State legislators | 1981 | Tennessee17 | 7/8 (88) | |

| Country club members | 1978 | Minnesota18 | 97/102 (95) | |

| Residents of a trailer park | 1982 | Bartow County, GA19 | 31/35 (89) | |

| Military prison | 1982 | Kansas16 | 35/46 (76) | |

| Sought care: noninstitutionalized, household population | 2012 | United States20 | (88) | 88.0 |

| Underreporting to health department | 68.7 | |||

| Health department | 1987 | Pierce County, WA21 | 14/15 (93) | |

| Managed care organization | 2008 | Massachusetts22 | 1/4 (25) | |

| Hepatitis B | ||||

| Frequency of symptoms | 39.5 | |||

| Weight loss clinic | 1986 | California23 | 27/60 (45) | |

| Pain clinic outbreak | 2004 | Oklahoma24 | 13/31 (42) | |

| Injection drug users | 2003 | Natrona County, WY25 | 27/45 (60) | |

| State correctional facility | 2000 | Undisclosed26 | 2/6 (33) | |

| Inpatient surgeries | 1992 | Undisclosed27 | 6/19 (32) | |

| 2 dialysis centers | 1996 | Allegheny County, PA28 | 0/6 (0) | |

| Private physician office | 2005 | New York, NY29 | 4/38 (11) | |

| Assisted living facility | 2010 | Illinois30 | 7/8 (88) | |

| Orthopedic surgeon office | 2010 | Virginia31 | 1/2 (50) | |

| Injection drug users | 2002 | Seattle, WA32 | 14/63 (22) | |

| Injection drug users | 2004 | Montana33 | 11/21 (52) | |

| Nursing home | 2004 | Mississippi34 | 2/15 (13) | |

| Nursing home | 2003 | North Carolina34 | 1/11 (9) | |

| Hematology oncology clinic | 2009 | New Jersey35 | 16/19 (84) | |

| Outpatient gastroenterology facility | 2005 | New York, NY36 | 2/6 (33) | |

| Nursing home | 2012 | North Carolina37 | 3/6 (50) | |

| Nursing home | 2012 | North Carolina38 | 0/6 (0) | |

| Psychiatric long-term care | 2012 | Cook County Illinois38 | 5/8 (63) | |

| Ambulatory psychiatric residents | 2008 | California39 | 6/9 (67) | |

| Sought care: noninstitutionalized, household population | 2012 | United States20 | (88) | 88.0 |

| Underreporting | 44.5 | |||

| Active surveillance of population | 1987 | Pierce County, WA21 | 19/27 (70) | |

| Managed care organization | 2008 | Massachusetts40 | 4/8 (50) | |

| Injection drug users | 2002 | Seattle32 | 2/14 (14) | |

| Hepatitis C | ||||

| Frequency of symptoms, injection drug users | 12.8 | |||

| Injection drug users | 2011 | Massachusetts41 | 4/28 (14) | |

| Injection drug users | 2002 | Seattle32 | 4/53 (8) | |

| Injection drug users | 2004–2007 | New York State42 | 4/20 (20) | |

| Frequency of symptoms, non–injection drug users | 47.6 | |||

| Pain clinic outbreak | 2004 | Oklahoma24 | 40/71 (56) | |

| Pain clinic outbreak | 1999–2002 | Oklahoma43 | 27/47 (57) | |

| Hematology and oncology clinics | 2001 | Nebraska44 | 16/99 (16) | |

| Cardiology and radiology clinics | 2006 | Maryland45 | 15/16 (94) | |

| Medical facilities, blood donors | 2007 | Multiple US sites46 | 24/67 (36) | |

| Dialysis clinic | 2006 | Virginia47 | 3/7 (43) | |

| Research agency patients | 2011 | National Institutes of Health, MD48 | 20/25 (80) | |

| HIV-infected men | Unknown | New York, NY49 | 3/11 (28) | |

| Outpatient gastroenterology facility | 2005 | New York, NY36 | 3/6 (50) | |

| Outpatient dialysis facility | 2012 | Georgia19 | 0/4 (0) | |

| Sought care: noninstitutionalized, household population | 2012 | United States20 | (88) | 88.0 |

| Underreporting | 53.0 | |||

| Active surveillance of a population | 1987 | Pierce County, WA21 | 16/38 (42) | |

| 6 health departments | 2008 | CO, CT, MN, OR, New York City, New York State50 | 102/120 (85) | |

| Injection drug users | 2002 | Seattle, WA32 | 0/4 (0) | |

In 2010, there were an estimated 262 000 persons with viral hepatitis who also reported a usual (regular) source of medical care. The prevalence of these events together was 3.2% (95% confidence interval [CI] = 2.9%, 3.5%) among all respondents. Among persons reporting a hepatitis infection, 88.0% (95% CI = 84.5%, 91.6%) said they had a usual source of care. The inverse of this proportion (1.14) is presented (sought care) in Table 2.

TABLE 2—

Multipliers Used to Estimate the Number of New Infections With Hepatitis A, B, and C: United States, 2011

| Hepatitis Type | Multiplier |

Actual Case Patients Reported 2011 | Estimated Number of Infectionsa | Final Multipliers (Infection–Case Ratio) | ||

| Symptomatic | Sought Care | Reported to Surveillance | ||||

| A | 1.18 | 1.14 | 1.46 | 1398 | 2730 | 1.95 |

| B | 2.54 | 1.14 | 2.25 | 2890 | 18 730 | 6.48 |

| C | 12.30 | |||||

| Injection drug use | 7.81 | 1.14 | 1.89 | 937 | 15 770 | |

| Other risk factor | 2.10 | 1.14 | 1.89 | 293 | 1330 | |

Rounded to the nearest 10.

There were 1398 case patients with HAV, 2890 with acute HBV, and 1230 with acute HCV reported to NNDSS during 2011 (Table 2). Of the case patients with acute HCV reported, we assigned 937 (76%) as having injected drug use as a risk factor; we assigned the remaining 293 to a source of infection other than injection drug use (e.g., receipt of unscreened blood, infection in health care settings).

The inverse values of the pooled estimates and resulting multipliers from the studies are presented in Table 2. For 2011 we estimated 2730 HAV infections, or 1.95 new infections for each case patient reported to the CDC. For HBV, we estimated 18 730 infections, or 6.48 infections per reported case patient. For HCV, we estimated 17 100 infections, or 12.30 infections per case patient with an acute infection.

DISCUSSION

We found that there were an estimated 38 560 new patients with acute HAV, HBV, or HCV infections during 2011. That is, for every reported individual with HAV, there were an estimated 2.0 new infections; for every reported individual with acute HBV, there were actually about 6.5 new infections; and for every reported individual with acute HCV, about 12.3 new infections. These estimates of numbers of acute infections are essential for health departments to evaluate the success of prevention activities, including vaccination for HAV and HBV, infection control practices in health care settings, and education and needle exchange and drug treatment programs for injecting drug users.

There may be other methods to estimate the number of all acute infections. For example, estimates of acute HCV infections could be derived from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey by testing all specimens, about 5000 per year, for HCV RNA52; however, the extensive resources needed to conduct such testing are not available, and the small numbers generated would still lead to very wide statistical CIs on the estimate. Furthermore, these numbers probably would not be useful for state and local health departments.

These updated adjustment factors are somewhat lower than are those the CDC used in the past.7 However, previous methods used to estimate infections, as published in annual national surveillance reports, had not been updated or recalculated for many years and depended heavily on knowledge of the epidemiology on the basis of small cohorts of transfusion recipients in the 1990s.53 We included recent literature and outbreaks, so our multipliers are more likely to indicate the current number of new infections.

Case reports sent electronically to CDC are useful for examining gross trends in acute HAV, HBV, and HCV infections; all of these have been declining markedly in the past 10 years.10 Specifically, HAV declined 87%, HBV declined 63%, and HCV declined 25% since 2001.7 HAV and HBV are thought to result from increasing vaccination coverage of the population, especially the youngest age groups. However, the steep decline in the number of case patients with acute HCV over the past 2 decades is more difficult to explain but may be related to changes in behavior among injecting drug users, screening the blood supply since 1992, and changes in standard precautions—many of these in reaction to the HIV/AIDS epidemic in the United States.54

In 2010, the Institute of Medicine recommended removing the criterion for symptoms from the case definitions for acute HBV and HCV.55 However, laboratory indicators for acute infection are available only for HAV and HBV (immunoglobulin M antibodies), not for HCV, and many individuals with acute infections of all 3 viral hepatitides are determined from overt symptoms, such as jaundice. To be tested, an infected person must seek care; asymptomatic persons might not seek care. Thus, removing symptoms from the case definitions would not allow back-calculation as performed in our analysis.

These estimates are limited mainly in that we had to impute the estimates for 2 criteria—proportion of symptomatic persons seeking care and then reported to local and state health departments—from indirect and sparse data. Similarly, the distribution of injecting drug users among case patients with acute HCV is from a small study (n = 21). We could not determine whether the frequency of responding to the 2 questions in the National Health Interview Survey represented an over- or underestimate of the frequency with which persons with hepatitis actually sought care because no published studies measured that event. There have been few studies directed to assessing the underreporting of persons diagnosed with acute viral hepatitis. We did not measure variability or uncertainty in the model parameters, but we expect to quantify these as a next step. Thus, these estimates should be viewed as the best that can be generated at this time to support surveillance, planning, and prevention activities until better data sets or more sophisticated models can be developed.

Many acute infections of HAV, HBV, and HCV continue to occur. The estimates and methods we have described can be used at the national, state, and local levels to estimate burden and control and prevent new hepatitis infections. Continued monitoring of individuals with symptomatic infections and periodic estimation of all infections are essential to understanding the magnitude of the problem and evaluating the impact of prevention.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Peng Jun Lu at the Immunization Services Division, National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for his analysis of National Health Interview Survey data to provide the proportion of persons who said they had hepatitis and a place to go for care.

Human Participant Protection

No protocol approval was needed for this study because data used were publicly available. No human participants were involved.

References

- 1.Klevens RM, Miller JT, Iqbal K et al. The evolving epidemiology of hepatitis A in the United States: incidence and molecular epidemiology from population-based surveillance, 2005–2007. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(20):1811–1818. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Multiple outbreaks of hepatitis B virus infection related to assisted monitoring of blood glucose among residents of assisted living facilities—Virginia, 2009–2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61(19):339–343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Investigation of viral hepatitis infections possibly associated with health-care delivery—New York City, 2008–2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61(19):333–338. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wasley A, Kruszon-Moran D, Kuhnert W et al. The prevalence of hepatitis B virus infection in the United States in the era of vaccination. J Infect Dis. 2010;202:192–201. doi: 10.1086/653622. 2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Armstrong GL, Wasley A, Simard EP, McQuillan GM, Kuhnert WL, Alter MJ. The prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection in the United States, 1999 through 2002. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144(10):705–714. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-10-200605160-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ly KN, Xing J, Klevens RM, Jiles RB, Ward JW, Holmberg SD. The increasing burden of mortality from viral hepatitis in the United States between 1999 and 2007. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156(4):271–278. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-156-4-201202210-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Viral hepatitis surveillance—United States. 2011 Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/statistics/index.htm. Accessed November 13, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reed C, Angulo FJ, Swerdlow DL et al. Estimates of the prevalence of pandemic (H1N1) 2009, United States, April–July 2009. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15(12):2004–2007. doi: 10.3201/eid1512.091413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosner BA. Fundamentals of Biostatistics. 5th ed. Pacific Grove, CA: Duxbury; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Viral hepatitis outbreaks. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/outbreaks/index.htm. Accessed November 11, 2013.

- 11.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Health Interview Survey. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis.htm. Accessed February 5, 2013.

- 12.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/osels/ph_surveillance/nndss/casedef/case_definitions.htm. Accessed February 5, 2013.

- 13.McGovern BH, Birch CE, Bowen MJ et al. Improving the diagnosis of acute hepatitis C virus infection with expanded viral load criteria. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49(7):1051–1060. doi: 10.1086/605561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wheeler C, Vogt TM, Armstrong GL et al. An outbreak of hepatitis A associated with green onions. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(9):890–897. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Positive test results for acute hepatitis A virus infection among persons with no recent history of acute hepatitis—United States, 2002–2004. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2005;54(18):453–456. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lednar WM, Lemon S, Kirkpatrick J, Redfield R, Fields M, Kelley P. Frequency of illness associated with epidemic hepatitis A virus infections in adults. Am J Epidemiol. 1985;122(2):226–233. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gustafson TL, Hutcheson RH, Jr, Fricker RS, Schaffner W. An outbreak of foodborne hepatitis A: the value of serologic testing and matched case-control analysis. Am J Public Health. 1983;73(10):1199–1201. doi: 10.2105/ajph.73.10.1199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Osterholm MT, Kantor RJ, Bradley DW et al. Immunoglobulin M-specific serologic testing in an outbreak of foodborne viral hepatitis, type A. Am J Epidemiol. 1980;112(1):8–16. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bloch AB, Stramer SL, Smith JD et al. Recovery of hepatitis A virus from a water supply responsible for a common source outbreak of hepatitis A. Am J Public Health. 1990;80(4):428–430. doi: 10.2105/ajph.80.4.428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2010 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) survey description. Available at: ftp://ftp.cdc.gov/pub/Health_Statistics/NCHS/Dataset_Documentation/NHIS/2010/srvydesc.pdf. Accessed February 5, 2013.

- 21.Alter MJ, Mares A, Hadler SC, Maynard JE. The effect of underreporting on the apparent incidence and epidemiology of acute viral hepatitis. Am J Epidemiol. 1987;125(1):133–139. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Automated detection and reporting of notifiable diseases using electronic medical records versus passive surveillance—Massachusetts, June 2006–July 2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008;57(14):373–376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Hepatitis B associated with jet gun injection—California. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1986;35(23):373–376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Comstock RD, Mallonee S, Fox JL et al. A large nosocomial outbreak of hepatitis C and hepatitis B among patients receiving pain remediation treatments. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2004;25(7):576–583. doi: 10.1086/502442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vogt TM, Perz JF, Van Houten CK, Jr et al. An outbreak of hepatitis B virus infection among methamphetamine injectors: the role of sharing injection drug equipment. Addiction. 2006;101(5):726–730. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01407.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Hepatitis B outbreak in a state correctional facility, 2000. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2001;50(25):529–532. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harpaz R, Von Seidlein L, Averhoff FM et al. Transmission of hepatitis B virus to multiple patients from a surgeon without evidence of inadequate infection control. N Engl J Med. 1996;334(9):549–554. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199602293340901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hutin YJ, Goldstein ST, Varma JK et al. An outbreak of hospital-acquired hepatitis B virus infection among patients receiving chronic hemodialysis. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1999;20(11):731–735. doi: 10.1086/501573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Samandari T, Malakmadze N, Balter S et al. A large outbreak of hepatitis B virus infections associated with frequent injections at a physician’s office. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2005;26(9):745–750. doi: 10.1086/502612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Counard CA, Perz JF, Linchangco PC et al. Acute hepatitis B outbreaks related to fingerstick blood glucose monitoring in two assisted living facilities. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(2):306–311. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02669.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Enfield KB, Sharapov U, Hall K Transmission of hepatitis B virus to patients from an orthopedic surgeon. Paper presented at: 20th Annual Scientific Meeting of the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America; March 20, 2010; Atlanta, GA.

- 32.Hagan H, Snyder N, Hough E et al. Case-reporting of acute hepatitis B and C among injection drug users. J Urban Health. 2002;79(4):579–585. doi: 10.1093/jurban/79.4.579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Garfein RS, Bower WA, Loney CM et al. Factors associated with fulminant liver failure during an outbreak among injection drug users with acute hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2004;40(4):865–873. doi: 10.1002/hep.20383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Transmission of hepatitis B virus among persons undergoing blood glucose monitoring in long-term-care facilities—Mississippi, North Carolina, and Los Angeles County, California, 2003–2004. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2005;54(9):220–223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Greeley RD, Semple S, Thompson ND et al. Hepatitis B outbreak associated with a hematology–oncology office practice in New Jersey, 2009. Am J Infect Control. 2011;39(8):663–670. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2010.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gutelius B, Perz JF, Parker MM et al. Multiple clusters of hepatitis virus infections associated with anesthesia for outpatient endoscopy procedures. Gastroenterology. 2010;139(1):163–170. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.03.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Williams RE, Sena AC, Moorman AC et al. Hepatitis B vaccination of susceptible elderly residents of long term care facilities during a hepatitis B outbreak. Vaccine. 2012;30(21):3147–3150. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.02.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jasuja S, Thompson ND, Peters PJ et al. Investigation of hepatitis B virus and human immunodeficiency virus transmission among severely mentally ill residents at a long-term care facility. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(8) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043252. e43252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wise ME, Marquez P, Sharapov U et al. Outbreak of acute hepatitis B virus infections associated with podiatric care at a psychiatric long-term care facility. Am J Infect Control. 2012;40(1):16–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2011.04.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Klompas M, Haney G, Church D, Lazarus R, Hou X, Platt R. Automated identification of acute hepatitis B using electronic medical record data to facilitate public health surveillance. PLoS ONE. 2008;3(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002626. e2626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Notes from the field: risk factors for hepatitis C virus infections among young adults—Massachusetts, 2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(42):1457–1458. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Use of enhanced surveillance for hepatitis C virus infection to detect a cluster among young intravenous drug users—New York, 2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008;57(19):517–521. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fazili J, Mallonee S, Tierney WM et al. Outcome of a hepatitis C outbreak among patients in a pain management clinic. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55(6):1738–1743. doi: 10.1007/s10620-010-1228-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Macedo de Oliveira A, White KL, Leschinsky DP et al. An outbreak of hepatitis C virus infections among outpatients at a hematology/oncology clinic. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142(11):898–902. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-142-11-200506070-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Patel PR, Larson AK, Castel AD et al. Hepatitis C virus infections from a contaminated radiopharmaceutical used in myocardial perfusion studies. JAMA. 2006;296(16):2005–2011. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.16.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang CC, Krantz E, Klarquist J et al. Acute hepatitis C in a contemporary US cohort: modes of acquisition and factors influencing viral clearance. J Infect Dis. 2007;196(10):1474–1482. doi: 10.1086/522608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Thompson ND, Novak RT, Datta D et al. Hepatitis C virus transmission in hemodialysis units: importance of infection control practices and aseptic technique. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2009;30(9):900–903. doi: 10.1086/605472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Loomba R, Rivera MM, McBurney R et al. The natural history of acute hepatitis C: clinical presentation, laboratory findings and treatment outcomes. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33(5):559–565. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04549.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fierer DS, Uriel AJ, Carriero DC et al. Liver fibrosis during an outbreak of acute hepatitis C virus infection in HIV-infected men: a prospective cohort study. J Infect Dis. 2008;198(5):683–686. doi: 10.1086/590430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Evaluation of acute hepatitis C infection surveillance—United States, 2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59(43):1407–1410. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mbaeyi C. Outbreak of hepatitis C virus infections in an outpatient dialysis facility—Georgia, 2011. Paper presented at: 61st Annual Epidemic Intelligence Service Conference; April 16–20, 2012; Atlanta, GA.

- 52.Page-Shafer K, Pappalardo BL, Tobler LH et al. Testing strategy to identify cases of acute hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection and to project HCV incidence rates. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46(2):499–506. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01229-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Alter MJ.Epidemiology of hepatitis C Hepatology 1997263 suppl 1)62S–65S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Klevens RM, Hu DJ, Jiles R, Holmberg SD. Evolving epidemiology of hepatitis C virus in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55(suppl 1):S3–S9. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Institute of Medicine. Hepatitis and Liver Cancer: A National Strategy for Prevention and Control of Hepatitis B and C. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]