ABSTRACT

Enteroviruses, which represent a large genus within the family Picornaviridae, undergo important conformational modifications during infection of the host cell. Once internalized by receptor-mediated endocytosis, receptor binding and/or the acidic endosomal environment triggers the native virion to expand and convert into the subviral (altered) A-particle. The A-particle is lacking the internal capsid protein VP4 and exposes N-terminal amphipathic sequences of VP1, allowing for its direct interaction with a lipid bilayer. The genomic single-stranded (+)RNA then exits through a hole close to a 2-fold axis of icosahedral symmetry and passes through a pore in the endosomal membrane into the cytosol, leaving behind the empty shell. We demonstrate that in vitro acidification of a prototype of the minor receptor group of common cold viruses, human rhinovirus A2 (HRV-A2), also results in egress of the poly(A) tail of the RNA from the A-particle, along with adjacent nucleotides totaling ∼700 bases. However, even after hours of incubation at pH 5.2, 5′-proximal sequences remain inside the capsid. In contrast, the entire RNA genome is released within minutes of exposure to the acidic endosomal environment in vivo. This finding suggests that the exposed 3′-poly(A) tail facilitates the positioning of the RNA exit site onto the putative channel in the lipid bilayer, thereby preventing the egress of viral RNA into the endosomal lumen, where it may be degraded.

IMPORTANCE For host cell infection, a virus transfers its genome from within the protective capsid into the cytosol; this requires modifications of the viral shell. In common cold viruses, exit of the RNA genome is prepared by the acidic environment in endosomes converting the native virion into the subviral A-particle. We demonstrate that acidification in vitro results in RNA exit starting from the 3′-terminal poly(A). However, the process halts as soon as about 700 bases have left the viral shell. Conversely, inside the cell, RNA egress completes in about 2 min. This suggests the existence of cellular uncoating facilitators.

INTRODUCTION

Human rhinoviruses (HRVs) are the major cause of usually mild but recurrent infections of the respiratory tract affecting everybody on the planet (1). The cause of the resulting discomfort is not cell lysis, but rather inflammation paired with a massive production of mucus triggered by the induction of cytokines and reactive oxygen species. Although rarely serious, the disease results in decreased labor productiveness and lost working hours (2); therefore, HRVs are of enormous economic importance (3).

In weaning infants and the elderly, infections can become life-threatening, particularly when affecting the lungs and in combination with asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or cystic fibrosis (4). To date, efforts toward development of effective and well-tolerated drugs have not been successful. The currently available compounds have side effects that are only acceptable when the condition of the patient necessitates last-resort intervention (5, 6). Vaccination has been considered impracticable because of the existence of more than 160 different genotypes with poor immunological cross-reactivity (7); nevertheless, more recent research has identified antigenic epitopes shared among a number of HRVs that might be a starting point for the production of immunogens suitable for vaccination (8–10).

HRVs include three species: HRV-A, -B, and -C (11). They are phylogenetically closely related to the four human enterovirus species, which comprise more serious pathogens such as poliovirus and enterovirus 71 (EV71) among many others, all belonging to the genus Enterovirus, family Picornaviridae, of single-stranded (+)RNA viruses (12). They possess an icosahedral protein shell of ∼30 nm in diameter that is composed of 60 copies each of the capsid proteins VP1 through VP4. The genome is about 7,200 nucleotides in length. At the 5′ end, instead of a cap structure, the genomic RNA carries a 21-amino-acid peptide referred to as VPg. A genome-encoded poly(A) tract (13) between 20 and 150 nucleotides in length (14) is present at its 3′ end.

In addition to the classification above, HRV-A and -B are divided into a minor and a major receptor group; the former group includes 12 HRV-A types which bind low-density lipoprotein receptors and related membrane proteins, whereas the latter group binds intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1) and comprises more than 89 representatives of HRV-A and HRV-B (15). A particular feature of the icosahedral protein shell is the canyon, a deep cleft encircling the star-shaped dome at the 5-fold axis of symmetry. Whereas the minor group receptors attach to the dome of the protein shell, ICAM-1 binds inside the canyon. The HRV-C receptor(s) is unknown.

Upon binding its respective receptor, the virus is taken up into the cell, where it undergoes major structural modifications. Protein domains, in particular those of VP1 and VP2, become displaced, resulting in expansion of the capsid by ca. 4% (16). Antiparallel helices of two adjacent copies of VP2 (residues 90 to 98) at the 2-fold axes veer away from each other, resulting in the opening of pores. These movements are possible because of a hydrophobic pocket below the canyon of the protein shell; in native virus this void is occupied by a fatty acid that is released during uncoating, thus providing the necessary space for amino acid residues to move, as reported previously (16). Cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) three-dimensional (3D) image reconstructions of the related poliovirus during uncoating triggered by heating to 56°C demonstrated that the genomic RNA most probably exits from one of these pores (17). The sizes of the pores are sufficient only for passage of the nucleic acid as a single strand, suggesting that the genome must unwind prior to exiting the particle. This view is further supported by the finding that an intercalating dye prebound to the viral genome is stripped off during in vivo uncoating (18).

The conversion of poliovirus (19) and HRV-A2 (20) into A-particles results in additional density appearing close to the tips of the three-bladed propeller at the 3-fold axes. This density is thought to stem from about 30 N-terminal residues of VP1; indeed, Fab fragments raised against a peptide derived from this segment were found to attach to this site (21). The amphipathic VP1 segment exposed in the A-particle might “crawl up” the canyon wall along the shoulder to the star-shaped dome; in the presence of cellular membranes, it presumably interacts with the lipid bilayer (19, 22, 23). The exit sites of the N-terminal VP1 sequences identified in poliovirus were shown to correspond to small channels in the expanded empty capsids of EV71 (24, 25) and HRV-A2. This observation suggests that the externalized segments retract upon completion of RNA exit (16).

By triggering HRV-A2 uncoating by heating to 56°C, as previously done in poliovirus studies on RNA release (17, 26), we recently demonstrated that RNA trapped inside the capsid takes on the shape of a thick rod pointing in the direction of a 2-fold axis and a 3-fold axis, at roughly opposite sides of the shell, suggesting a role in the “tail-first” (i.e., 3′-end first) release process (27). Particles with these internal structures were much more frequently observed when double-stranded regions in the RNA had been cross-linked with psoralen. This suggests that the RNA adopts this peculiar conformation when uncoating is halted and regions behind the exiting segment cannot be unwound. In our cryo-EM images of in vitro acidified HRV-A2, such density was not observed. This disparity implies that the “condensation” of the RNA might be related to the (unphysiological) cross-linking and/or heating. Therefore, the role of this structure, if any, in in vivo uncoating is still enigmatic.

To assess whether RNA egress occurs with the same directionality under a setting more closely resembling the situation in the living cell, we repeated and extended our previous experiments using acidification, as naturally occurs in endosomes in vivo, instead of incubation at 56°C, to trigger the conversion of native virus into subviral particles.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents.

All chemicals, oligonucleotides, and enzymes were obtained from Sigma unless otherwise noted.

Cells and virus.

HeLa-Ohio cells were obtained from Flow Laboratories; they are now available from the European Collection of Cell Cultures (Salisbury, United Kingdom). HRV-A2 was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC VR-482) and maintained in the laboratory. The following primers were used: 5′-end-reverse, 5′-dAAGGGTTAAGGTTAGCCACATTCAG-3′; 5′-end-forward, 5′-dGACCAATAGCCGGTAATCAG-3′, primer1-reverse, 5′-dAGCTTTAACTTCCCTGCCTG-3′; primer1-forward, 5′-dACCCTCTCAACCAGATACATC-3′; M-oligo-reverse, 5′-dAAGGTGTCAGTGTTATTTATTGGTACTAGGCTG-3′; M-oligo-forward, 5′-dGCCCCATGTGTGCAGAGTTTTC-3′; primer2-reverse, 5′-dAATTGCTGTCTGAATACTCC-3′; primer2-forward, 5′-dATGATGGGTATGATGAACAAG-3′; primer3-reverse, 5′-dTCTTTGTGTATATAATTAAGCTG-3′; primer3-forward, 5′-dTGTGGATAGTGTAAAAGAAC-3′; and primer4-reverse, 5′-dACATCAACCACTTGTCTTCTC-3′; primer4-forward, 5′-dGCACAAATCATTCCCTTCTAAC-3′; primer5-reverse, 5′-dAACACTAGGCTGCAATTTG-3′; primer5-forward, 5′-dACGGCTAGAATGCTTAAATAC-3′; 3′-end3-reverse, 5′-dCCACTCATGCAAAAGCAAATC-3′; 3′-end3-forward, 5′-dCCTTCCCTGAAGATAAATATTTGAATCC-3′; 3′-end5-reverse, 5′-dCTCTGGATCACATCCAACTGCTGATCCAG-3′; 3′-end5-forward, 5′-dGAGTTGACTTACCTATGGTCACC-3′; primer6-reverse, 5′-dTTTTTTTTTTTTTATAAAACTAATA-3′; and primer6-forward, 5′-dGAGTTGACTTACCTATGGTCACC-3′.

FCS.

Fluorescence correlation spectroscopy (FCS) was carried out in a Confocor 1 instrument (Zeiss) as in previous work (27). The fluorescence autocorrelation function was determined for DyLight488-labeled oligonucleotides complementary to HRV-A2 genome sequences at the 3′ end [25-mer oligo(dT)] and the 5′ end (positions 443 to 468) in 75 mM KCl–3 mM MgCl2–50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.3) after the addition of native virus (control) and acidified and reneutralized virus, respectively. Between 10 and 30 independent measurements were taken, with a data acquisition time of 10 s each. Optimal molar ratios between oligonucleotide and free RNA (and the subviral particle with partially exposed RNA) were as determined previously (27). HRV-A2 (at 1 μM) was mixed with the respective labeled oligonucleotide (at 50 nM). One volume of this mixture was acidified by adding 1.5 vol of 50 mM sodium acetate (NaOAc; pH 5.2) and incubated at 34°C, and samples (10 μl) were withdrawn at the times indicated in the figures and reneutralized on ice by the addition of 10 μl of 100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.3). All samples were supplemented with 2 U of RNasin (Promega)/μl. FCS was then carried out at ambient temperature. Translational diffusion times and the percentages of the second and third components were calculated with the FCS Access software (version 1.0.12) using one- and two-component fit models as described previously (27).

Capillary electrophoresis.

An automated HP3D capillary electrophoresis system (Hewlett Packard, Waldbronn, Germany) equipped with an uncoated fused-silica capillary was used throughout (27). Detector signals were recorded in fast spectral scanning mode to allow for monitoring at more than one wavelength. A positive polarity mode (negative pole placed at the capillary outlet) at 25 kV was used for all experiments. HRV-A2 was acidified by incubation in 50 mM NaOAc (pH 5.2) at 34°C for 15 min. To detect viral RNA outside the virion (but still connected to it), 1 μl (1 μg) anti-dsRNA monoclonal antibody (MAb) J2 (English and Scientific Consulting kit) per sample (6 μg of HRV-A2 in 19 μl) was added, followed by incubation for 20 min at room temperature. For the detection of accessible poly(A) tails, samples were incubated with poly(U) (25-mer) at a final concentration of 0.5 μM for 10 min at room temperature prior to the addition of MAb J2. All samples were run in 100 mM borate buffer (pH 8.3) containing 10 mM Thesit (polyethylene glycol 400 dodecyl ether [28]).

Extraction of RNA from the agarose gel and reverse transcription-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR).

Native HRV-A2 and subviral particles resulting from acidification were incubated with micrococcal nuclease (MNase) at 37°C for 20 min and run on a 0.7% agarose gel in TAE buffer (20 mM Tris–10 mM acetic acid–5 mM EDTA [pH 8.0]), followed by staining with GelGreen (Biotium). Bands corresponding to intermediate subviral particles (whose accessible RNA had been digested) and native HRV-A2, respectively, were excised, and RNA within the particles was extracted by using a Zymoclean gel RNA recovery kit (Zymo Research). RT was carried out with Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (Promega), followed by PCR for 30 cycles using GoTaq HotStart polymerase (Promega) and the primer sets indicated in the figures and used previously (27). qPCR was performed by using a KAPA SYBR Fast quantitative PCR kit (Peqlab) in an Eppendorf master cycler. All samples were run in duplicate.

Uncoating in vivo.

HeLa-Ohio cells grown in suspension were infected with HRV-A2 at a multiplicity of infection of 1,000. In control experiments, cells were preincubated at 34°C for 30 min with niclosamide at 2 μM, and the drug was maintained at the same concentration throughout the experiment. Virus was allowed to attach to cells in suspension at 4°C for 4 h with gentle shaking. Unbound virus was removed by washing two times with cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), the cells were resuspended in 1 ml of infection medium for suspension culture, and bound virus was allowed to be internalized synchronously at 34°C for the times indicated in the figures. The infected cells were harvested via centrifugation, washed with PBS, resuspended in 500 μl of PBS containing 10 mM Thesit, and broken with a Dounce homogenizer with a tight-fitting pestle. The cell debris was removed by low-speed centrifugation, and viral uncoating intermediates were immunoprecipitated using MAb 2G2 (29) bound to magnetic protein A-beads (Dynabeads-Protein A; Life Technologies). Accessible RNA was digested with 10 U of MNase/sample at room temperature for 10 min.

Cellular fractionation.

Subcellular fractions (see Fig. 5, left lanes) were prepared essentially as described in references 30 and 31. Briefly, HeLa-Ohio cells grown in suspension culture (5 × 108) were collected, washed with PBS, resuspended in 3 volumes of hypotonic buffer (1.5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM KCl, 0.2 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 0.5 M dithiothreitol, 10 mM HEPES [pH 7.9]), and allowed to swell on ice for 10 min. Cells were broken in a Dounce homogenizer with 15 strokes using a loose-fitting pestle. Cell lysis was monitored under the microscope. Debris, nuclei, mitochondria, and aggregates were removed at 15,000 × g for 15 min. A 0.11 volume of 0.3 M HEPES (pH 7.9), 1.4 M KCl, 30 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), and the proteinase inhibitors pepstatin A and leupeptin hemisulfate salt (at final concentrations of 2 and 0.6 μM, respectively) was added, and an aliquot (designated “cyto”) was kept. The remainder was ultracentrifuged at 100,000 × g for 60 min at 4°C; the supernatant was designated S100. The pellet (P100) was resuspended in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4) containing proteinase inhibitors as described above.

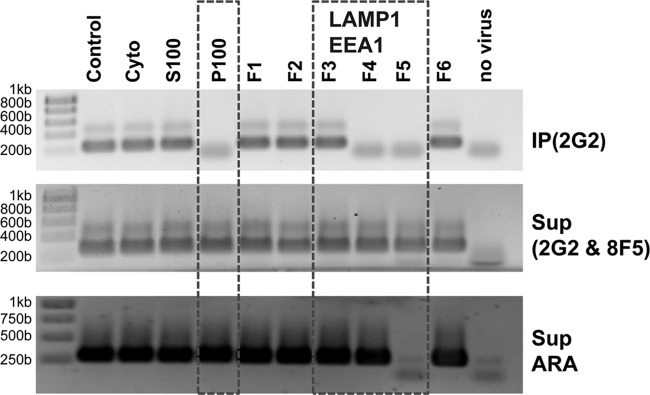

FIG 5.

HeLa microsomal fraction promotes RNA uncoating. HRV-A2 was acidified in the presence of subcellular fractions (left) or of microsomal fractions obtained from a sucrose density step gradient (right). For the upper panel, subviral particles were immunoprecipitated with MAb 2G2, and RNA was extracted from the immunoprecipitates and analyzed for the presence of 5′-proximal sequences via RT-PCR using primer pair M, followed by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis and GelGreen staining. To exclude loss of the RNA via digestion by contaminating RNases, the supernatant was again immunoprecipitated, but now with MAb 8F5 (66) to remove any remaining native virus. RNA was then extracted from the supernatant and analyzed as described above. As a control, an irrelevant RNA (ARA; Arabidopsis mRNA containing ubiquitin-encoding sequences) was added to all samples prior to immunoprecipitation and RNA extraction and was detected with a ubiquitin-specific primer set. Fractions framed were positive for LAMP1 and EEA1, as determined via Western blotting (data not shown). Lower bands are from the primers. To exclude contamination of the reaction mixture with viral RNA, RT-PCR was carried out without the addition of viral material (negative control). The results from one of five independent experiments are shown.

Preparation of microsomal fractions (Fig. 5, right lanes) was essentially as described previously (32). HeLa-Ohio cells (108) grown in suspension culture were collected at 1,200 rpm for 15 min in a Heraeus Megafuge 1.0, resuspended in 40 ml of PBS, incubated for 10 min at room temperature in PBS containing 0.02% EDTA, and then pelleted again. The resuspended pellet was washed twice with 150 mM NaCl–1 mM Ca(OAc)2–50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4) and once with 20 mM Tris-HCl–10 mM EDTA (pH 7.4), and the cells were pelleted, resuspended in 5 ml of Tris-EDTA buffer, and incubated for 15 min at 4°C. The swollen cells were then broken in a Dounce homogenizer with 18 strokes using a tight-fitting pestle. Cell homogenization was monitored under the microscope. Larger debris, nuclei, and aggregates were removed by centrifugation in a table-top Eppendorf centrifuge at 900 × g for 5 min. The supernatants were transferred into SW40 centrifuge tubes and mixed with 75% (wt/wt) sucrose in 2 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.0) to give a 50% final sucrose concentration. A step gradient was created by overlaying this dense solution with 2.7 ml of 35% (wt/wt) sucrose, 2.7 ml of 30% (wt/wt) sucrose, and 2 ml of 25% (wt/wt) sucrose in the same buffer. Finally, 1 ml of plain buffer was applied, and the tube was centrifuged in a SW40 rotor at 26,000 rpm for 17 h at 0°C. Three turbid bands were identified visually and collected from the top down in a total of 6 fractions (F1–F6). These were diluted approximately 1:3 with 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.0), and membranes were pelleted for 1 h at 0°C at 70,000 × g using a TLS100 rotor (Beckman). The pellet was resuspended in 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.0) containing 0.2 mM PMSF, 2 μM pepstatin A, and 0.6 μM leupeptin. The volumes were adjusted to contain roughly the same protein concentration as determined with a NanoDrop instrument from Peqlab (fractions 1 and 2 were very low in protein and used undiluted).

Western blotting and immunodetection of marker proteins.

To localize early endosomes and lysosomes, aliquots were analyzed by Western blotting with suitable antibodies. About 20 μg of total protein of each fraction was separated on a 12% reducing polyacrylamide-sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) gel and transferred onto a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane using a Fast Semi-Dry blotter (Thermo Scientific). Membranes were blocked with 3% (wt/vol) bovine serum albumin in PBS and processed for immunodetection with mouse anti-EEA1 (BD Transduction Laboratories) and mouse anti-LAMP1 (Developmental Studies Hybridoma), respectively. As a secondary antibody, goat anti-mouse-horseradish peroxidase (Jackson Laboratories) was used. EEA1 and LAMP1 were visualized via chemiluminescence (SuperSignal; Invitrogen).

In vitro RNA uncoating in the presence of cellular fractions.

Virus was mixed with the microsomal fractions at a final protein concentration of ∼1 mg/ml in the presence of RNasin (4 U/μl; Promega). In the control sample the microsomal fraction was replaced with 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7). In addition, aliquots of the fractions were preincubated in 10 mM Thesit for 15 min at room temperature for lysis of vesicles prior to mixing with virus. Samples were incubated at room temperature for 10 min, 1.5 volume of 50 mM NaOAc (pH 5.2) was added, and incubation continued at 34°C for 15 min. Samples were reneutralized by the addition of the same volume of 100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.3). Where detergent was not yet present, a 0.11 volume of 100 mM Thesit in 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7) was added, and the uncoating intermediates were collected via immunoprecipitation.

Immunoprecipitation.

As a control for nonspecific RNase digestion, all samples were supplemented with 2 μg/μl of Arabidopsis mRNA (kindly provided by A. Barta, Medical University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria). Immunoprecipitation was carried out with MAb 2G2 and protein A-magnetic beads as described above. To exclude contamination with viral nucleic acids, buffer alone was processed identically as a negative control. (Sub)viral particles in the immunoprecipitates were disintegrated with 200 μl of 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7) containing 1% (wt/vol) SDS at 70°C for 5 min. Released viral RNA was then precipitated from the supernatant with ethanol in the presence of 1 μg of glycogen/μl as a carrier and used for RT-PCR employing the M-oligo primer set (see above). In parallel, the integrity of the added control RNA was assessed by RT-PCR using primers specific for Arabidopsis ubiquitin (also generously provided by A. Barta). In control incubations with niclosamide, MAb 2G2 was replaced with rabbit polyclonal antiserum against HRV-A2.

RESULTS

Incubation of HRV-A2 at pH 5.2 results in exposure of 3′-terminal sequences of the genomic RNA, but 5′-proximal sequences remain protected inside the viral shell.

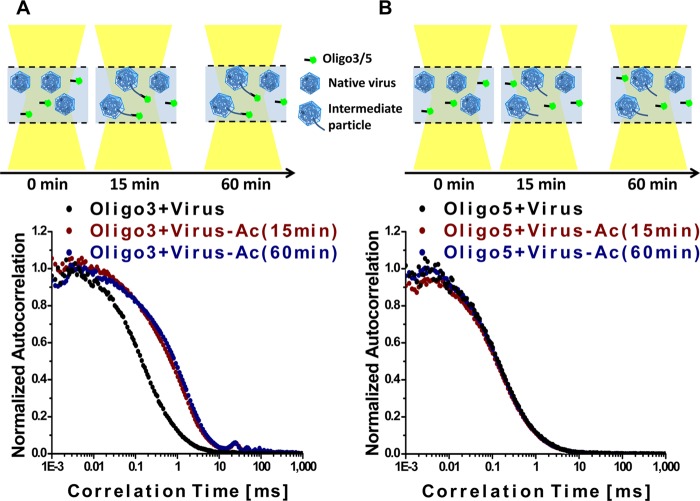

HRV-A2 was incubated in NaOAc buffer (pH 5.2) (33–37) at 34°C, the optimal replication temperature of HRV, for 15 and 60 min and then reneutralized on ice. RNA sequences derived from the 3′ and 5′ ends, having eventually become accessible, were then separately determined with fluorescence correlation spectroscopy (FCS) as previously described for virus heated to 56°C (27). The FCS setup used measures the diffusion of a fluorescent oligonucleotide; when such a probe hybridizes to cognate sequences present in free and/or incompletely released RNA (still connected to the virion), its diffusion is slowed (reviewed in reference 38; see Table 1 for the respective diffusion coefficients. The autocorrelation curves in Fig. 1A show that incubation at 34°C and pH 5.2, followed by reneutralization, led to exposure of poly(A) sequences present at the 3′ end at 15 min but not at 0 min (control). Extension of the incubation at acidic pH to 60 min left the autocorrelation curve unchanged, indicating that the number of subviral particles carrying accessible 3′-terminal sequences capable of hybridizing to the oligo(dT) remained the same and that no free RNA was appearing. At neither time point were 5′-proximal sequences accessible to the cognate 5′-specific oligonucleotide (Fig. 1B). This can be deduced from the lack of a shift in the autocorrelation curve in Fig. 1B, indicating that free 5′-oligonucleotide was the only fluorescent component present. The respective components detected with this setup are indicated in the diagrams. The current results are strikingly different from those obtained when uncoating was triggered via heating; in the latter case, the entire RNA was released within about 20 min (27). These data imply that sequences close to the 5′ end of the viral genome remained inaccessible inside the capsid for at least up to 60 min of incubation at pH 5.2 at 34°C, and thus no empty capsids were found (see below).

TABLE 1.

Diffusion coefficients of labeled 5′-oligonucleotide and oligo(dT) upon binding to free viral RNA and to RNA connected to the virion, respectivelya

| Oligonucleotide alone or in combination with virus | Mean ± SD |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3′Oligo(dT) |

5′-Oligonucleotide |

|||

| D [(10−12)m2/s] | % | D [(10−12)m2/s] | % | |

| Oligo | 75.7 ± 1.8 | 76.9 ± 1.7 | ||

| Oligo + virus (0 min) | 25.4 ± 2.4 | 18.7 ± 2.5 | 21.1 ± 2.5 | 13.1 ± 1.4 |

| Oligo + virus-Ac (15 min) | 9.2 ± 0.3 | 88.2 ± 1.8 | 27.3 ± 2.4 | 19.2 ± 2.8 |

| Oligo + virus-Ac (60 min) | 9.9 ± 0.6 | 77.4 ± 2.1 | 16.9 ± 1.6 | 9.4 ± 1.3 |

The diffusion coefficient (D) of the free oligonucleotide or the corresponding second component after incubation with virus and acidification for different time periods, as well as the corresponding fractions of these components, are presented. Standard deviations were calculated from three independent experiments in which each measurement was taken between 10 and 30 times. Diffusion coefficients were derived according to the equation below by fitting the obtained autocorrelation curves, g(t), to the model.

FIG 1.

Sequences at the 3′ end of the viral RNA, including the poly(A) tail, become accessible upon acidification of native HRV-A2 at 34°C. Normalized autocorrelation curves of A) DyLight 488-labeled oligo(dT) incubated with native virus (black) and with virus incubated at pH 5.2 for 15 min (red) and for 60 min (blue). (B) Same as in panel A, but in the presence of an oligonucleotide complementary to a sequence close to the 5′ end (positions 443 to 468). The diagrams show the components present in the incubation mixtures and their interactions. Note the absence of free RNA and of sequences recognized by the 5′-specific oligonucleotide at all time points.

RNA exposed on acidification is recognized by dsRNA-specific antibodies only after hybridization with poly(U).

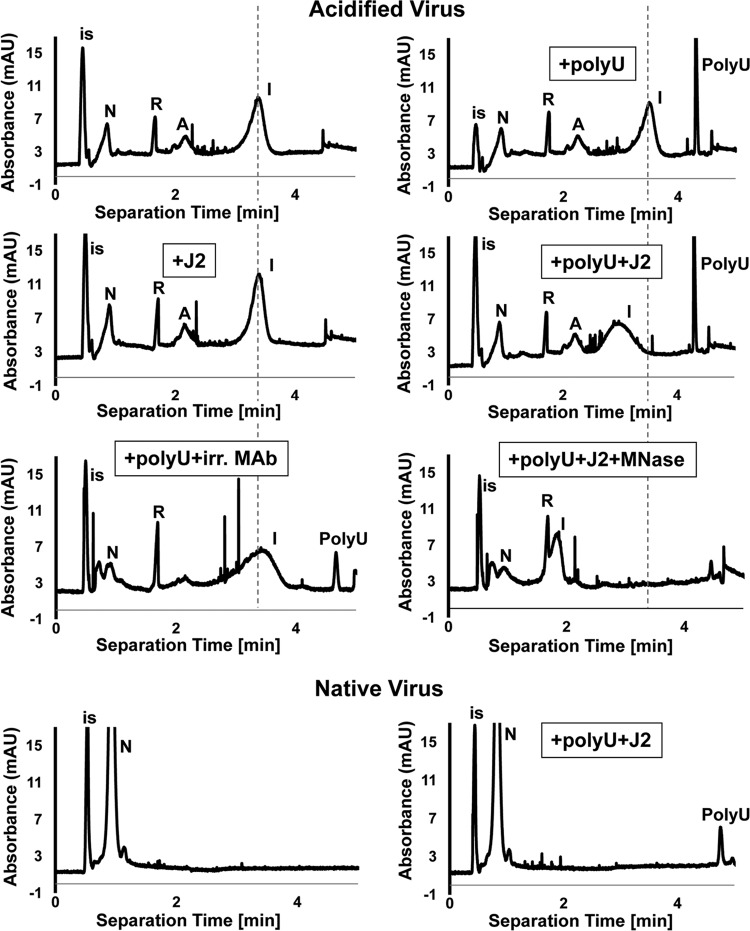

In previous work we had detected externalized RNA by using the double-stranded RNA (dsRNA)-specific monoclonal antibody (MAb) J2 (39); when HRV-A2 was subjected to psoralen cross-linking followed by heating, addition of this antibody led to a clear shift in migration of the generated subviral particles in capillary electrophoresis. This was taken to indicate that MAb J2 bound to partially released RNA that had refolded into double-stranded regions (27). On repeating such experiments, but using acidification instead of heating for triggering the formation of subviral particles (as in Fig. 1), no change in the position of the broad peak of these “intermediate particles” (i.e., A-particles with partially extruded RNA, denoted “I”) was observed in the presence of MAb J2 (compare Fig. 2, upper left panels). Rather, the particles continued to migrate identically to the previously characterized intermediate particles (27, 40) and differently from native virus (N). We thus reasoned that the exposed RNA segments might not fold into double strands long enough to be recognized by MAb J2. Furthermore, although poly(A) can form double strands at acidic pH, it fails to do so at neutral pH (41), and uridine-rich sequences suitable for base pairing with the poly(A) appear to be absent from the externalized sequences.

FIG 2.

RNA sequences externalized on incubation of HRV-A2 at pH 5.2 are not recognized by dsRNA-specific MAb J2, as shown by capillary electrophoresis. Acidified or native virus, as indicated, were incubated with the specified components and analyzed by capillary electrophoresis. The subviral particle exposing RNA (“intermediate particle” [I]) migrates as a broad peak at a position different from that of the A-particle (see also reference 27). Upon removal of the exposed RNA sequences with MNase, the particle comigrates with the A-particle. Note that the addition of poly(U) together with MAb J2, but neither one alone, modified the migration of intermediate particles. Note that the replacement of MAb J2 with an irrelevant antibody (anti-γ-tubulin) at the same concentration had no effect on the migration of viral or subviral particles. Finally, note that native virus did not change its migration upon the addition of poly(U) together with MAb J2, demonstrating the absence of accessible poly(A) sequences. Internal standard (is), dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). Broken vertical lines indicate the position of the “intermediate particles.” Electropherograms were calibrated to the migration of DMSO and, where present, of RNasin (R). N, native virus; A, A-particle.

Poly(A)/poly(U) hybrids are recognized by MAb J2 (39); we thus added poly(U) prior to incubation with the antibody. As seen in Fig. 2 (compare upper right panels) and in accordance with the literature (42), the added poly(U) apparently hybridized to the externalized and obviously accessible poly(A) and gave rise to double strands that were now recognized by MAb J2. This resulted in a shift and broadening of the intermediate particle peak. Together with the above FCS results, these results strongly suggest that exposure of HRV-A2 to acidic buffer leads to exit of the poly(A) tail and presumably of upstream sequences with a low tendency to form double-stranded regions recognizable by MAb J2. Thus, incubation of HRV-A2 at pH 5.2 initializes uncoating, but the RNA does not exit completely even after overnight incubation (data not shown); its continued egress requires cellular factors (see below). No shift in migration of the intermediate particles was seen when incubated with poly(U) and an irrelevant antibody or when the virus-poly(U)-J2 complex was treated with MNase.

Upon acidification in vitro, about 700 bases upstream of the 3′ end become exposed.

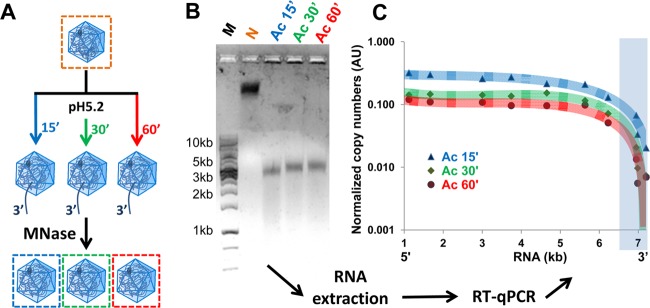

To determine the extent of acid-triggered RNA release more precisely, we modified the RT-PCR protocol previously used for the determination of sequences protected from MNase in psoralen UV-cross-linked and heated HRV-A2 (27). Virus was incubated for 0, 15, 30, and 60 min in pH 5.2 buffer at 34°C. The samples were reneutralized and cooled to 4°C as described above, accessible RNA was digested with MNase (Fig. 3A), and the resulting subviral particles were separated from the degradation products via agarose gel electrophoresis (Fig. 3B). Bands were excised, the RNA was extracted, and sequences that remained protected inside the capsid were quantified with RT-qPCR by using a graded set of roughly evenly spaced oligonucleotide primer pairs (Fig. 3C). Figure 3B shows that native, MNase-treated HRV-A2 gave rise to a band close to the top of the agarose gel, whereas acidified, MNase-treated virus migrated further down. There was no obvious difference in the migration when incubation at pH 5.2 was for 15, 30, or 60 min. Apparently, despite the A-particle being expanded by 4% compared to the native virion (20), the RNA core is easily accessible for ions because of the various channels in the subviral particle shell (20), thus imparting on it a strong overall negative charge resulting in accelerated migration. Alternatively, loss of the charge-neutralizing polyamines (43) may explain this unexpected migration behavior. We assumed a copy number of 1 for all sequence stretches flanked with a primer pair in native virus. Nevertheless, as the band of HRV-A2 stained much more strongly with GelGreen (and Coomassie brilliant blue [data not shown]) than those of the subviral particles, we refrained from normalizing the data because of the obvious loss of material presumably due to aggregation impeding entry of part of the A-particles into the gel. Indeed, where acidified virus was applied, the gel pockets showed much stronger staining than in case of native virus (see Fig. 3B). For this reason, the data in Fig. 3C is reported as relative, rather than absolute copy numbers of capsid-internal sequences along the genome as a function of incubation time at acidic pH. It is evident that 3′-proximal nucleotides quickly egressed on acidification and consequently rapidly disappeared upon subsequent MNase treatment. However, even at 60 min, sequences from the 5′ end extending to a region around position 6500 were still protected. In conclusion, roughly 700 3′-proximal bases exit immediately, but further egress of the RNA molecule occurs extremely slowly, if at all.

FIG 3.

At pH 5.2, HRV-A2 releases an RNA segment, including about 700 residues at the 3′ end. (A) Diagram illustrating the procedure. Virus was incubated in acidic buffer at 34°C for the times indicated, the buffer was reneutralized, and the accessible RNA was digested. (B) Native HRV-A2 (control) and the subviral particles resulting from this treatment were separated on a 0.7% agarose gel. RNA within the particles was visualized with GelGreen. DNA markers were run in the leftmost lane. (C) RNA was extracted from the bands in panel B, and the presence of sequences was assessed with RT-qPCR using primer pairs hybridizing to the indicated positions in the viral genome. The number of copies is given as an arbitrary number. The approximate trend of the time-dependent loss of RNA sequences (from 3′ to 5′) is indicated by a trend plot.

In vivo, the entire viral genome is released within about 2 min.

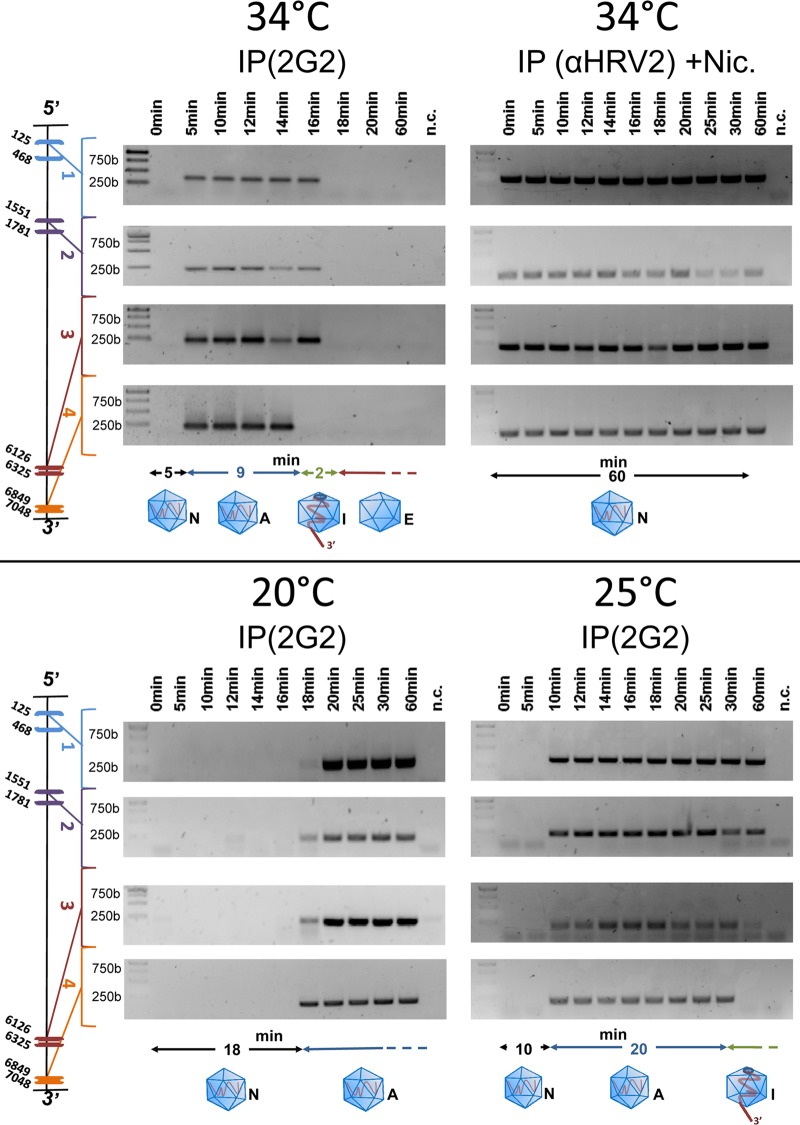

It was previously determined, using MAb 2G2 that specifically recognizes A- and B-particles but not native virus (44), that HRV-A2 converts into subviral particles in HeLa cells in less than 15 min (45). This includes entry and transport to late endosomes where pH 5.6, the threshold for structural modification (46) is attained. At 10 min, viral RNA accessible to a FISH probe can already be detected in the perinuclear area of the infected cells (47). We thus wanted to know how quickly the entire RNA is released from the virion in vivo. HeLa cells were allowed to internalize at 34°C, and entry/uncoating was halted via transferring the samples to ice at the time points given in Fig. 4. Cells were homogenized, and subviral particles were immunoprecipitated with MAb 2G2 to exclude background from residual native virus that is not recognized by this antibody. RNA outside the virion was digested, and specific RT-PCR was carried out on the sequences that had remained protected from the nuclease inside the capsid. As a control, niclosamide was added to the cells prior to viral challenge (Fig. 4, upper right panel). This drug neutralizes the intra-endosomal pH, preventing conversion of native virus into A-particles (48). As indicated in Fig. 4 (upper left panel), 3′-end proximal sequences were detected at time points between 5 and 14 min postinfection, but were absent from the subviral particles on infection times equal to or longer than 16 min. On the other hand, 5′-proximal sequences remained detectable for up to 16 min postinfection but then also disappeared. Thus, unlike the partial egress observed after acidification in vitro, RNA egress in vivo went to completion. Taking into account that RNA exit has just started as soon as 3′-terminal sequences are no longer detected inside the viral shell and is complete when no 5′-terminal sequences remain, the entire process takes about 2 min at 34°C. Note that no RNA was detected at 0 min because native virus is not recognized by 2G2 and thus not immunoprecipitated. Nevertheless, its presence can be inferred from the control experiment in which polyclonal antiserum against HRV-A2 was used; these antibodies do not discriminate between native virus and subviral particles (upper right panel). In the latter experiment, 3′ and 5′ proximal sequences remained detectable for up to 60 min, the time of observation. As expected, the virus thus remained intact in the presence of the drug.

FIG 4.

In vivo release of viral RNA is rapid. HeLa cells (106) grown in suspension culture were suspended in 1 ml of infection medium, and HRV-A2 (multiplicity of infection of 1,000) was allowed to attach at 4°C for 4 h. The cells were then washed with PBS, resuspended in fresh infection medium, and incubated for the indicated times. Next, the cells were lysed, intermediate particles were collected via immunoprecipitation with 2G2, externalized RNA was digested with MNase, and protected sequences were identified with RT-PCR using the primer pairs complementary to the viral genome at the positions indicated at the left. In the upper right panel (control), uncoating was inhibited via addition of niclosamide (Nic), present during the whole experiment, and immunoprecipitation was performed with polyclonal rabbit antiserum directed against HRV-A2 (αHRV-A2). Experiments were carried out at the temperatures indicated under otherwise identical conditions. The status of the virion and of its RNA is shown as a diagram below the gels; black line, time of conversion into A-particle; blue line, time until the 3′ end becomes accessible from the A-particle; green line, time until complete RNA release. N, native; A, A-particle; I, intermediate particle (with partially released RNA); E, empty capsid.

Compared to the incomplete in vitro uncoating above, in vivo uncoating at 34°C was completed in roughly 2 min. It appears to be initiated upon arrival of the virions in an endosomal compartment with a pH of ≤5.6. Since trafficking from early to late endosomes (and further to lysosomes) is strongly temperature dependent, we also explored uncoating at 20 and 25°C. As also seen in Fig. 4 (lower panels), viral RNA sequences were detected much later at 25°C and even more so at 20°C. This temperature effect presumably results from prolonged trafficking times that lead to delayed conversion of the virion into A-particles and consequently of recognition by 2G2. Whereas viral RNA can be detected upon infection at 34°C within roughly 5 min, it is seen only after 10 and 18 min at 25 and 20°C, respectively. Does uncoating still work at these lower temperatures? At 34°C, the 3′ end becomes accessible to MNase between about 14 and 16 min, as seen from its absence at the latter time point. At 25°C it did so between 30 and 60 min. Finally, at 20°C it did not seem to become externalized to an appreciable degree for up to 60 min when the experiment was terminated. Furthermore, at least for up to 60 min, 5′-proximal sequences remained protected at these lower temperatures, whereas uncoating was complete in roughly 2 min at 34°C. Collectively, these experiments suggest that uncoating is easily initiated [i.e., the 3′ poly(A) is still released at 25°C, although at a diminished speed], but the remainder of the genome is only extruded at higher temperatures and only in vivo.

Upon in vitro acidification in the presence of a microsomal fraction, RNA exit goes to completion.

The large difference between in vitro and in vivo RNA release upon acidification suggests that cellular factors are required for the complete and rapid exit of the viral genome. Since RNA transfer from within the capsid to the cytosol occurs inside endosomes, such a factor might be expected to accumulate in a microsomal fraction. Microsomes isolated from homogenized cells include inside-in and, at a lower proportion, inside-out vesicles; the latter reform on closure of membrane sheets (49). Thus, such facilitators are expected to be accessible in cellular extracts. HeLa cells were homogenized and membranes were collected by high-speed centrifugation. These samples were then fractionated by sucrose density step gradient centrifugation. Both crude subcellular fractions and microsome-enriched fractions were analyzed for their capacity to promote viral uncoating at low pH. The presence of the endosomal and lysosomal markers, early endosomal antigen 1 (EEA1) and lysosome associated membrane protein 1 (LAMP1), respectively, was also assessed. Virus was incubated with the respective membrane fractions, acidified, and the extent of RNA release was estimated after immunoprecipitation with MAb 2G2. To control for nonspecific degradation, irrelevant Arabidopsis mRNA, including sequences encoding ubiquitin, was added to all samples. RNA extracted from the immunoprecipitates and RNA in the supernatants was tested for the presence of 5′-proximal sequences by RT-PCR as described above. As seen in Fig. 5, except when acidified in the presence of the resuspended membrane pellet (V+P100; for the preparation of the membrane fractions, see Materials and Methods) and membrane fractions 4 and 5 (F4 and F5) from the sucrose density step gradient, the 5′-proximal sequences of the viral RNA remained detectable inside the virion, indicating a lack of complete uncoating. In the remaining samples, no RNA was detected, implying complete release and/or degradation. Except in the sample incubated in the presence of membrane fraction 5, nonspecific degradation could be definitely excluded, because the control RNA was intact (Fig. 5, lower panel). In all supernatants of the immunoprecipitates, viral RNA with intact 5′ sequences was found (middle panel). It was most probably derived from remaining intact virus (compare this to the in vitro experiment discussed in Fig. 2). Therefore, fraction 4 appears to contain a factor which promotes exit of the entire viral RNA genome on acidification.

DISCUSSION

The recent determination of the 3D structures of three enterovirus empty capsids to near atomic resolution (16, 25, 50) revealed important details of the conformational rearrangement occurring on transition of the native virion into the subviral intermediate of RNA uncoating. The native virion expands, loses VP4, and externalizes N-terminal segments of VP1. As shown in the present study, it also externalizes the poly(A) tail, together with several hundred upstream nucleotides. This stretch corresponds to roughly 10% of the total RNA, a number similar to an earlier estimate of ca. 7%, based on the UV absorbance ratios at 200 and 260 nm of the peaks of native virus and RNase-treated intermediate-particles in capillary electrophoresis (51).

Most likely, similar to poliovirus (17), the RNA exits through one of the channels close to the 2-fold axes in a timely, coordinated fashion to allow for its efficient transfer into the cytosol for replication. Egress of the RNA is believed to occur after the A-particle dissociates from the receptor (52); concomitantly, the particle might be handed over to the endosomal membrane, where the amphipathic N-terminal segments of VP1, and presumably VP4 set free during the process, insert into the membrane for its destabilization and pore formation (37, 53–55). Our observation that the poly(A) stretch already exits upon acidification adds a new dimension to the uncoating process; the 3′ end of the RNA might be actively participating in the correct positioning of the viral particle onto the inner endosomal membrane, thereby initiating and directing its transfer. Although the ratio between physical particles and infectious particles was estimated to be on the order of 24 up to 6,500 (56–58), it seems counterintuitive that the viral genome would exit randomly with 29 chances in 30 (there are 30 symmetry-related holes in the subviral particle) to end up in the lumen of the (late) endosome where it might be degraded.

It did not come as a great surprise that the 3′ poly(A) exits first (27), since not being involved in the formation of double strands might facilitate sampling the inner face of the capsid for the presence of holes. Alternatively, because of its peculiar features, it might become positioned, already during assembly, close to a 2-fold axis where a pore is to open on conversion of the native virion into the subviral A-particle. No Enterovirus counterpart to the maturation protein present as a single copy in the capsid of MS2 phage (59) has been found. Such proteins had been overlooked previously because of the icosahedral averaging intrinsic to X-ray crystallography and most often used in cryo-EM 3D-image reconstruction to increase the resolution. It is possible that asymmetry is introduced in enteroviruses by the presence of noncapsid proteins associated in spurious amounts with the shell, such as those involved in replication that were detected in highly purified foot-and-mouth disease virus, another picornavirus (60). Small amounts of VP0 have also been noticed in purified enteroviruses, and it has not been clarified whether they stem exclusively from natural empty capsids, the “natural top component” (35), or from individual virions containing a small proportion of VP0 that might establish asymmetry. It is conceivable that the presence of a few VP0 molecules could break the icosahedral symmetry, thus favoring RNA exit at a specific (presumably membrane-juxtaposed) location.

The difference between in vitro and in vivo uncoating is particularly striking. At least in the case of minor group HRVs, it cannot be explained by a “catalytic” function of the receptor; binding of a very-low density lipoprotein receptor mimetic, a head-to-tail concatemer of ligand-binding repeat V3 that exhibits high affinity for HRV-A2 (61) stabilizes the virus rather than aiding in its conversion to A-particles (62). This is dissimilar to major group viruses which are uncoated by an excess of soluble ICAM-1 alone (63). Furthermore, the presence of lipid membranes alone seems to assist RNA exit only marginally (36). The uncoating activity we found in the microsomal membrane fraction of HeLa cells is preserved after extensive dialysis but abrogated by detergents (data not shown). This might suggest that the process is energy independent but relies on intact membranes. Coxsackievirus B3 uncoating activity has been observed in membrane extracts previously (32, 64). Its receptor DAF does not have uncoating activity, but its second receptor CAR does have uncoating activity, which might explain this finding (65). Ongoing studies in our laboratory are aimed at characterizing the “HRV-A2 uncoating facilitator” identified in HeLa cell membrane fractions.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was made possible through Ph.D. program “Structure and Interaction of Macromolecules” funding (S.H.) and grant P20915-B13, both awarded by the Austrian Science Fund.

We thank Irene Gösler for virus preparation.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 26 March 2014

REFERENCES

- 1.Jacobs SE, Lamson DM, St George K, Walsh TJ. 2013. Human rhinoviruses. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 26:135–162. 10.1128/CMR.00077-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kennedy JL, Turner RB, Braciale T, Heymann PW, Borish L. 2012. Pathogenesis of rhinovirus infection. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2:287–293. 10.1016/j.coviro.2012.03.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Waterer G, Wunderink R. 2009. Respiratory infections: a current and future threat. Respirology 14:651–655. 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2009.01554.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gern JE. 2010. The ABCs of rhinoviruses, wheezing, and asthma. J. Virol. 84:7418–7426. 10.1128/JVI.02290-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rollinger JM, Schmidtke M. 2011. The human rhinovirus: human-pathological impact, mechanisms of antirhinoviral agents, and strategies for their discovery. Med. Res. Rev. 31:42–92. 10.1002/med.20176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Palma AM, Vliegen I, De Clercq E, Neyts J. 2008. Selective inhibitors of picornavirus replication. Med. Res. Rev. 28:823–884. 10.1002/med.20125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cooney MK, Fox JP, Kenny GE. 1982. Antigenic groupings of 90 rhinovirus serotypes. Infect. Immun. 37:642–647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Katpally U, Fu TM, Freed DC, Casimiro DR, Smith TJ. 2009. Antibodies to the buried N terminus of rhinovirus VP4 exhibit cross-serotypic neutralization. J. Virol. 83:7040–7048. 10.1128/JVI.00557-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Edlmayr J, Niespodziana K, Popow-Kraupp T, Krzyzanek V, Focke-Tejkl M, Blaas D, Grote M, Valenta R. 2011. Antibodies induced with recombinant VP1 from human rhinovirus exhibit cross-neutralization. Eur. Respir. J. 37:44–52. 10.1183/09031936.00149109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Glanville N, McLean GR, Guy B, Lecouturier V, Berry C, Girerd Y, Gregoire C, Walton RP, Pearson RM, Kebadze T, Burdin N, Bartlett NW, Almond JW, Johnston SL. 2013. Cross-serotype immunity induced by immunization with a conserved rhinovirus capsid protein. PLoS Pathog. 9:e1003669. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Palmenberg AC, Spiro D, Kuzmickas R, Wang S, Djikeng A, Rathe JA, Fraser-Liggett CM, Liggett SB. 2009. Sequencing and analyses of all known human rhinovirus genomes reveal structure and evolution. Science 324:55–59. 10.1126/science.1165557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ehrenfeld E, Domingo E, Roos RP. 2012. The picornaviruses. John Wiley & Sons, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tuthill TJ, Groppelli E, Hogle JM, Rowlands DJ. 2010. Picornaviruses. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 343:43–89. 10.1007/82_2010_37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ahlquist P, Kaesberg P. 1979. Determination of the length distribution of poly(A) at the 3′ terminus of the virion RNAs of EMC virus, poliovirus, rhinovirus, RAV-61, and CPMV and of mouse globin mRNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 7:1195–1204. 10.1093/nar/7.5.1195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Uncapher CR, Dewitt CM, Colonno RJ. 1991. The major and minor group receptor families contain all but one human rhinovirus serotype. Virology 180:814–817. 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90098-V [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garriga D, Pickl-Herk A, Luque D, Wruss J, Caston JR, Blaas D, Verdaguer N. 2012. Insights into minor group rhinovirus uncoating: the X-ray structure of the HRV2 empty capsid. PLoS Pathog. 8:e1002473. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bostina M, Levy H, Filman DJ, Hogle JM. 2011. Poliovirus RNA is released from the capsid near a twofold symmetry axis. J. Virol. 85:776–783. 10.1128/JVI.00531-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brandenburg B, Lee LY, Lakadamyali M, Rust MJ, Zhuang X, Hogle JM. 2007. Imaging poliovirus entry in live cells. PLoS Biol. 5:e183. 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bubeck D, Filman DJ, Cheng N, Steven AC, Hogle JM, Belnap DM. 2005. The structure of the poliovirus 135S cell entry intermediate at 10-Å resolution reveals the location of an externalized polypeptide that binds to membranes. J. Virol. 79:7745–7755. 10.1128/JVI.79.12.7745-7755.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pickl-Herk A, Luque D, Vives-Adrian L, Querol-Audi J, Garriga D, Trus BL, Verdaguer N, Blaas D, Caston JR. 2013. Uncoating of common cold virus is preceded by RNA switching as determined by X-ray and cryo-EM analyses of the subviral A-particle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 50:20063–20068. 10.1073/pnas.1312128110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lin J, Cheng N, Chow M, Filman DJ, Steven AC, Hogle JM, Belnap DM. 2011. An externalized polypeptide partitions between two distinct sites on genome-released poliovirus particles. J. Virol. 85:9974–9983. 10.1128/JVI.05013-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bostina M, Bubeck D, Schwartz C, Nicastro D, Filman DJ, Hogle JM. 2007. Single particle cryoelectron tomography characterization of the structure and structural variability of poliovirus-receptor-membrane complex at 30 Å resolution. J. Struct. Biol. 160:200–210. 10.1016/j.jsb.2007.08.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fricks CE, Hogle JM. 1990. Cell-induced conformational change in poliovirus: externalization of the amino terminus of VP1 is responsible for liposome binding. J. Virol. 64:1934–1945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shingler KL, Yoder JL, Carnegie MS, Ashley RE, Makhov AM, Conway JF, Hafenstein S. 2013. The enterovirus 71 A-particle forms a gateway to allow genome release: a cryo-EM study of picornavirus uncoating. PLoS Pathog. 9:e1003240. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang X, Peng W, Ren J, Hu Z, Xu J, Lou Z, Li X, Yin W, Shen X, Porta C, Walter TS, Evans G, Axford D, Owen R, Rowlands DJ, Wang J, Stuart DI, Fry EE, Rao Z. 2012. A sensor-adaptor mechanism for enterovirus uncoating from structures of EV71. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 19:424–429. 10.1038/nsmb.2255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Levy HC, Bostina M, Filman DJ, Hogle JM. 2010. Catching a virus in the act of RNA release: a novel poliovirus uncoating intermediate characterized by cryo-electron microscopy. J. Virol. 84:4426–4441. 10.1128/JVI.02393-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harutyunyan S, Kumar M, Sedivy A, Subirats X, Kowalski H, Kohler G, Blaas D. 2013. Viral uncoating is directional: exit of the genomic RNA in a common cold virus starts with the poly(A) tail at the 3′ end. PLoS Pathog. 9:e1003270. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kremser L, Petsch M, Blaas D, Kenndler E. 2006. Influence of detergent additives on mobility of native and subviral rhinovirus particles in capillary electrophoresis. Electrophoresis 27:1112–1121. 10.1002/elps.200500737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kremser L, Petsch M, Blaas D, Kenndler E. 2006. Capillary electrophoresis of affinity complexes between subviral 80S particles of human rhinovirus and monoclonal antibody 2G2. Electrophoresis 27:2630–2637. 10.1002/elps.200600066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Graham JM. 1972. Isolation and characterization of membranes from normal and transformed tissue-culture cells. Biochem. J. 130:1113–1124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Abmayr SM, Yao T, Parmely T, Workman JL. 2006. Preparation of nuclear and cytoplasmic extracts from mammalian cells. Curr. Protoc. Mol. Biol. Chapter 12:Unit 12.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Roesing TG, Toselli PA, Crowell RL. 1975. Elution and uncoating of coxsackievirus B3 by isolated HeLa cell plasma membranes. J. Virol. 15:654–667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Korant BD, Lonberg Holm K, Noble J, Stasny JT. 1972. Naturally occurring and artificially produced components of three rhinoviruses. Virology 48:71–86. 10.1016/0042-6822(72)90115-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lonberg Holm K, Noble Harvey J. 1973. Comparison of in vitro and cell-mediated alteration of a human rhinovirus and its inhibition by sodium dodecyl sulfate. J. Virol. 12:819–826 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lonberg-Holm K, Yin FH. 1973. Antigenic determinants of infective and inactivated human rhinovirus type 2. J. Virol. 12:114–123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bilek G, Matscheko NM, Pickl-Herk A, Weiss VU, Subirats X, Kenndler E, Blaas D. 2011. Liposomal nanocontainers as models for viral infection: monitoring viral genomic RNA transfer through lipid membranes. J. Virol. 85:8368–8375. 10.1128/JVI.00329-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weiss VU, Bilek G, Pickl-Herk A, Subirats X, Niespodziana K, Valenta R, Blaas D, Kenndler E. 2010. Liposomal leakage induced by virus-derived peptides, viral proteins, and entire virions: rapid analysis by chip electrophoresis. Anal. Chem. 82:8146–8152. 10.1021/ac101435v [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ries J, Schwille P. 2012. Fluorescence correlation spectroscopy. Bioessays 34:361–368. 10.1002/bies.201100111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bonin M, Oberstrass J, Lukacs N, Ewert K, Oesterschulze E, Kassing R, Nellen W. 2000. Determination of preferential binding sites for anti-dsRNA antibodies on double-stranded RNA by scanning force microscopy. RNA 6:563–570. 10.1017/S1355838200992318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Weiss VU, Subirats X, Pickl-Herk A, Bilek G, Winkler W, Kumar M, Allmaier G, Blaas D, Kenndler E. 2012. Characterization of rhinovirus subviral A particles via capillary electrophoresis, electron microscopy and gas-phase electrophoretic mobility molecular analysis: part I. Electrophoresis 33:1833–1841. 10.1002/elps.201100647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ke C, Loksztejn A, Jiang Y, Kim M, Humeniuk M, Rabbi M, Marszalek PE. 2009. Detecting solvent-driven transitions of poly(A) to double-stranded conformations by atomic force microscopy. Biophys. J. 96:2918–2925. 10.1016/j.bpj.2008.12.3939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schonborn J, Oberstrass J, Breyel E, Tittgen J, Schumacher J, Lukacs N. 1991. Monoclonal antibodies to double-stranded RNA as probes of RNA structure in crude nucleic acid extracts. Nucleic Acids Res. 19:2993–3000. 10.1093/nar/19.11.2993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fout GS, Medappa KC, Mapoles JE, Rueckert RR. 1984. Radiochemical determination of polyamines in poliovirus and human rhinovirus 14. J. Biol. Chem. 259:3639–3643 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hewat EA, Blaas D. 2006. Nonneutralizing human rhinovirus serotype 2-specific monoclonal antibody 2G2 attaches to the region that undergoes the most dramatic changes upon release of the viral RNA. J. Virol. 80:12398–12401. 10.1128/JVI.01399-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Neubauer C, Frasel L, Kuechler E, Blaas D. 1987. Mechanism of entry of human rhinovirus 2 into HeLa cells. Virology 158:255–258. 10.1016/0042-6822(87)90264-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gruenberger M, Pevear D, Diana GD, Kuechler E, Blaas D. 1991. Stabilization of human rhinovirus serotype-2 against pH-induced conformational change by antiviral compounds. J. Gen. Virol. 72:431–433. 10.1099/0022-1317-72-2-431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brabec-Zaruba M, Pfanzagl B, Blaas D, Fuchs R. 2009. Site of human rhinovirus RNA uncoating revealed by fluorescent in situ hybridization. J. Virol. 83:3770–3777. 10.1128/JVI.00265-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jurgeit A, McDowell R, Moese S, Meldrum E, Schwendener R, Greber UF. 2012. Niclosamide is a proton carrier and targets acidic endosomes with broad antiviral effects. PLoS Pathog. 8:e1002976. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hinton RH, Mullock BM. 1996. Isolation of subcellular fractions, p 31–69 In Rickwook JM. (ed), Subcellular fractionation: a practical approach, vol 1 Oxford University Press, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ren J, Wang X, Hu Z, Gao Q, Sun Y, Li X, Porta C, Walter TS, Gilbert RJ, Zhao Y, Axford D, Williams M, McAuley K, Rowlands DJ, Yin W, Wang J, Stuart DI, Rao Z, Fry EE. 2013. Picornavirus uncoating intermediate captured in atomic detail. Nat. Commun. 4:1929. 10.1038/ncomms2889 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Subirats X, Weiss VU, Gosler I, Puls C, Limbeck A, Allmaier G, Kenndler E. 2013. Characterization of rhinovirus subviral A particles via capillary electrophoresis, electron microscopy and gas phase electrophoretic mobility molecular analysis: part II. Electrophoresis 34:1600–1609. 10.1002/elps.201200686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Brabec M, Baravalle G, Blaas D, Fuchs R. 2003. Conformational changes, plasma membrane penetration, and infection by human rhinovirus type 2: role of receptors and low pH. J. Virol. 77:5370–5377. 10.1128/JVI.77.9.5370-5377.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Davis MP, Bottley G, Beales LP, Killington RA, Rowlands DJ, Tuthill TJ. 2008. Recombinant VP4 of human rhinovirus induces permeability in model membranes. J. Virol. 82:4169–4174. 10.1128/JVI.01070-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Konecsni T, Berka U, Pickl-Herk A, Bilek G, Khan AG, Gajdzig L, Fuchs R, Blaas D. 2009. Low pH-triggered beta-propeller switch of the low-density lipoprotein receptor assists rhinovirus infection. J. Virol. 83:10922–10930. 10.1128/JVI.01312-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kumar M, Blaas D. 2013. Human rhinovirus subviral a particle binds to lipid membranes over a twofold axis of icosahedral symmetry. J. Virol. 87:11309–11312. 10.1128/JVI.02055-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Abraham G, Colonno RJ. 1984. Many rhinovirus serotypes share the same cellular receptor. J. Virol. 51:340–345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Butterworth BE, Grunert RR, Korant BD, Lonberg-Holm K, Yin FH. 1976. Replication of rhinoviruses. Arch. Virol. 51:169–189. 10.1007/BF01318022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sachs LA, Schnurr D, Yagi S, Lachowicz-Scroggins ME, Widdicombe JH. 2011. Quantitative real-time PCR for rhinovirus, and its use in determining the relationship between TCID50 and the number of viral particles. J. Virol. Methods 171:212–218. 10.1016/j.jviromet.2010.10.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dent KC, Thompson R, Barker AM, Hiscox JA, Barr JN, Stockley PG, Ranson NA. 2013. The asymmetric structure of an icosahedral virus bound to its receptor suggests a mechanism for genome release. Structure 21:1225–1234. 10.1016/j.str.2013.05.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Newman JF, Brown F. 1997. Foot-and-mouth disease virus and poliovirus particles contain proteins of the replication complex. J. Virol. 71:7657–7662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wruss J, Runzler D, Steiger C, Chiba P, Kohler G, Blaas D. 2007. Attachment of VLDL receptors to an icosahedral virus along the 5-fold symmetry axis: multiple binding modes evidenced by fluorescence correlation spectroscopy. Biochemistry 46:6331–6339. 10.1021/bi700262w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nicodemou A, Petsch M, Konecsni T, Kremser L, Kenndler E, Casasnovas JM, Blaas D. 2005. Rhinovirus-stabilizing activity of artificial VLDL-receptor variants defines a new mechanism for virus neutralization by soluble receptors. FEBS Lett. 579:5507–5511. 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.09.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Greve JM, Forte CP, Marlor CW, Meyer AM, Hooverlitty H, Wunderlich D, McClelland A. 1991. Mechanisms of receptor-mediated rhinovirus neutralization defined by two soluble forms of ICAM-1. J. Virol. 65:6015–6023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.McGeady ML, Crowell RL. 1979. Stabilization of ‘A' particles of coxsackievirus B3 by a HeLa cell plasma membrane extract. J. Virol. 32:790–795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Milstone AM, Petrella J, Sanchez MD, Mahmud M, Whitbeck JC, Bergelson JM. 2005. Interaction with coxsackievirus and adenovirus receptor, but not with decay-accelerating factor (DAF), induces A-particle formation in a DAF-binding coxsackievirus B3 isolate. J. Virol. 79:655–660. 10.1128/JVI.79.1.655-660.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Skern T, Neubauer C, Frasel L, Grundler P, Sommergruber W, Zorn M, Kuechler E, Blaas D. 1987. A neutralizing epitope on human rhinovirus type 2 includes amino acid residues between 153 and 164 of virus capsid protein VP2. J. Gen. Virol. 68:315–323. 10.1099/0022-1317-68-2-315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]