Abstract

Objective

We examined patterns and predictors of initiation of treatment for incident diabetes in an ambulatory care setting in the US.

Methods

Data were extracted from electronic health records (EHR) for active patients ≥35 years in a multispecialty, multiclinic ambulatory care organization with 1,000 providers. New onset type 2 diabetes and subsequent treatment were identified using lab, diagnosis, medication prescription, and service use data. Time from the first evidence of diabetes until initial treatment, either medication or education/counseling, was examined using a Kaplan-Meier hazards curve. Potential predictors of initial treatment were examined using multinomial logistic models accounting for physician random effects.

Results

Of 2,258 patients with incident diabetes, 55% received either medication or education/counseling (20% received both) during the first year. Of the treated patients, 68% received a treatment within the first four weeks, and 13% after initial 16 weeks. Strong positive predictors (p<0.01) of combined treatment were younger age, higher fasting glucose at diagnosis, obesity, and visits with an endocrinologist.

Conclusions

Among insured patients who have a primary care provider in a multispecialty health care system, incident diabetes is treated only half the time. Improved algorithms for identifying incident diabetes from the EHR and team approach for monitoring may help treatment initiation.

INTRODUCTION

Guidelines for type 2 diabetes recommend early initiation of therapy, with lifestyle counseling and medication offered concomitantly [1,2]. Studies have shown the importance of early identification and treatment of diabetes for preventing long-term complications [3]. Even in the pre-diabetic stage, initiation of lifestyle changes and medications are beneficial [4–8]. Existing studies suggest an epidemic of under-diagnosis and under-treatment of diabetes and its complications in the US [9–12].

Little is known about how incident diabetes is treated in ambulatory care practices. It is unknown, for example, how long it takes to receive treatment after the identification of diabetes, and patient and practice factors contributing to the timing of treatment initiation. Addressing such questions requires observation of real-world practices serving patients with varying demographics and clinical conditions, and longitudinally linked data on patient clinical history, utilization pattern and provider practice style [13,14].

We examined initial treatment of incident diabetes, utilizing data from electronic health records (EHRs), reflecting clinical practice in typical ambulatory care setting. We first describe timing and initial treatment choices for patients who are newly identified as having diabetes. We then evaluate demographic and clinical risk factors and service use pattern that are associated with initial treatment of diabetes.

METHODS

Study Setting and Data Source

The study used demographic and clinical data, including anthropometric measures, physician diagnoses, laboratory results and prescription medications, extracted from EpicCare® (Epic Systems, Verona WI) EHRs for the patients at a large multi-specialty, mixed-payer, outpatient, group practice with approximately 1,000 physicians in northern California. The EHR system has been in use since 2000 across all the clinics and providers included in the study. The demographic characteristics of the patients are similar to that of residents in the surrounding service area [15].

The study population included active patients of the health care system (i.e., those who visited primary care or endocrinology departments) who were age 35 years or older, never had type 1 diabetes and were not pregnant during the surveillance period: 1/1/2007 – 6/30/2010 (n=254,259). We then identified patients with type 2 diabetes. Evidence for type 2 diabetes included (1) two physician diagnosis of diabetes (ICD-9 codes 250.xx) in the EHR Problem List or (2) two abnormal laboratory values (fasting glucose, random glucose, oral glucose tolerance or HbA1c tests) according to the 2005 American Diabetes Association (ADA) guideline [16]. Among patients with type 2 diabetes (n=20,341), we excluded patients who had evidence of diabetes or diabetes treatment before the study entry. To ascertain “new” diabetes status, we further excluded patients who had been in the health care system less than one year before the first evidence of diabetes.

Among patients identified as having incident diabetes (n=3,237), we excluded patients with active cancer (554 patients) or serious kidney or liver disease (239 patients), based on clinical encounter diagnosis. Of the remaining 2,429 patients, we then excluded 171 patients who did not make contacts with a primary care physician during follow up period (i.e., from the initial evidence to 6/30/2011) to ensure that the study sample consisted of active primary care patients and thus did not receive care exclusively outside the health care system during the follow-up, leaving 2,258 patients included in the study. All analytical data sets were HIPAA de-identified and no patients were contacted for the study.

Treatment Options

Treatment options for diabetes include medication prescription or education/counseling. Education/counseling was defined to include attendance in classes focused on diabetes-related lifestyle management, physician-led shared medical appointments on diabetes, or individual counseling with dietitians or nutritionists (see http://www.pamf.org/diabetes/ for examples of classes). Participation in education/counseling sessions (whether it is reimbursed by payers, self-paid or free of charge) was documented in the EHR. All treatments occurred on or after confirmatory evidence of diabetes. We assessed guideline-adherent treatment options classified into: (1) both education/counseling and medication prescription, (2) medication prescription only, and (3) education/counseling only.

Covariates in Multivariate Models of Predictors of Treatment

For clinical risk factors for treatment, we examined baseline values of fasting glucose, HbA1c, obesity (BMI≥30 kg/m2), overweight (BMI≥25 kg/m2 and <30 kg/m2), systolic blood pressure, triglyceride, and low density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol. For all the clinical values, we used the value measured and recorded on the date nearest (within the window of 365 days prior to 30 days post) to the first evidence of diabetes. Patient demographic characteristics included were age, sex, insurance type, race/ethnicity, and limited English proficiency (i.e., primary language not English). We also included three indicators of service use during the first year following initial diagnosis of diabetes: (1) any visit to an endocrinology department, (2) a visit to other specialty or urgent care, and (3) no physician office visit.

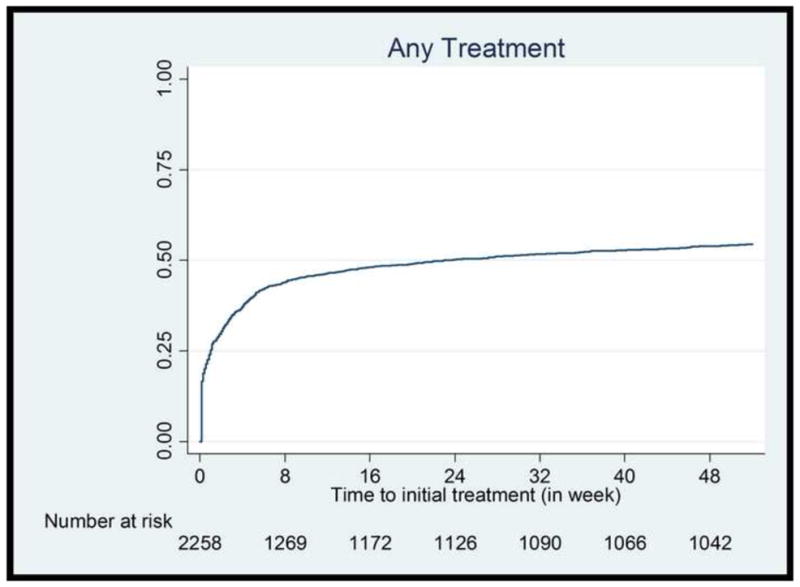

Statistical Analysis

To describe time to initial treatment, we computed a Kaplan-Meier cumulative treatment curve. The starting point was the date of first evidence of incident type 2 diabetes and the end point was the date of initial treatment or, if not treated, at the 12 months of follow-up.

We examined summary statistics and bivariate relationships of patient and physician characteristics with treatment options. Fisher’s exact test and X2 test were used for the bivariate comparisons, as appropriate.

For multivariate models, we used multinomial logistic model with four exclusive categories: both medication prescription and education/counseling, medication only, education/counseling only, and no treatment (base category). Physician (primary care provider of each patient) random effects model was used to take into account non-systematic variation within and across physicians. The results presented are exponentiated coefficients (eb) or relative risk ratios (RRR). All statistical analyses were conducted using Stata 11.2 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas).

RESULTS

Demographic, Clinical and Service Use Characteristics

The average age of 2,258 patients with incident diabetes was 56.9 years; less than half (43%) were female (Table 1). The majority were non-Hispanic white (53%) followed by Asian (35%). About 9% had limited English proficiency. PPO (61%) was most common insurance type.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics and initial treatment.

| Numbers represent mean [SD] or frequency (%) | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Variable (unit)[range] | All Patients with Incident Diabetes (N=2,258) |

| Patient demographic and clinical characteristics | |

| Age [35, 88 (top-coded)] | 56.9 [13.9] |

| Female | 974 (43.1) |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| Non-Hispanic white | 1,188 (52.6) |

| Asian | 779 (34.5) |

| African American or Black | 47 (2.1) |

| Hispanic or Latino | 244 (10.8) |

| Limited English proficiency | 197 (8.7) |

| Insurance type | |

| PPO | 1,383 (61.3) |

| HMO | 807 (35.7) |

| Other insurance | 20 (0.9) |

| Clinical risk factors at baselinea | |

| Fasting glucose [58–771mg/dL or 3.2–42.8mmol/l] | 149.1mg/dL or 8.3mmol/L [60.5 mg/dL] |

| Glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1C) [5.0–16.5% or 5.4–23.6mmol/L] | 7.3% or 9.0 mmol/L [1.8%] |

| Obese | 898 (39.8) |

| Overweight | 670 (29.7) |

| High systolic blood pressure (>=140mmHg) | 527 [23.3] |

| High triglyceride (>=150mg/dL or >=1.7mmol/L) | 959 [42.5] |

| High LDL cholesterol (>=130mg/dL or >=3.4mmol/L) | 558 [24.7] |

| Service use during first follow up year | |

| Any primary care visit | 1,615 (71.5) |

| Any endocrinology visit | 58 (2.6) |

| Other specialty or urgent care visit only | 57 (2.5) |

| No clinic visit | 580 (25.7) |

|

| |

| Treatment in the first 12 months of diabetes incidence | |

| Both medication and education/counseling | 447 (19.8) |

| Medication only | 451 (20.0) |

| Education/counseling only | 346 (15.3) |

| No treatment | 1014 (44.9) |

Fasting glucose: N=2,009 (89.0%); HbA1c: N=1,714 (75.9%); for other clinical indicators (overweight, obese, high systolic blood pressure, high triglyceride and high LDL cholesterol), missing baseline measurement was coded as 0.

On average, fasting glucose value (the closest to diabetes onset) was 149mg/dL (or 8.3 mmol/L) and HbA1c was 7.3% (or 9.0mmol/L). Note that some patients did not have a positive lab value, either fasting glucose or HbA1c near baseline, because they were identified as having incident diabetes based solely on 2 or more physician diagnoses. Among the patients whose pre-baseline fasting glucose value was less than 126mg/dL (or 7.0mmol/L) or HbA1c value was less than 6.5% (or 7.8mmol/L)(n=1,003), however, a majority of them (n=608) did have a positive lab value, had anti-diabetic medication prescription, or received education/counseling during the post-12 months study period. The remainder probably had a sign of diabetes or lab values taken elsewhere on which physician diagnoses and treatment were based on. Such information may have been recorded in the EHR text fields or as a scanned document attachment, but we could not retrieve the textual data for this study due to potential identification issues. More than two thirds of patients were obese (40%) or overweight (30%).

Most patients (74%) made a visit to the clinic to see a physician during the first year after diagnosis. The remainder (26%) did not visit the clinic in the first year after diagnosis, but did visit the clinic in subsequent years. Most patients (72%) made a visit to a primary care physician, only 2.7% made a visit to an endocrinologist, and 2.5% made other specialty care (e.g., ophthalmology, immunology, rheumatology) or urgent care visits only.

Time to Initial Treatment of Type 2 Diabetes

About half (55%, n=1,244) of patients were treated with either medication or education/counseling during the first year follow-up period. When treated, the treatment tended to occur relatively quickly (Fig. 1). Among those who were treated during the first year, 570 (46%) initiated the treatment in the first week, 840 (68%) initiated the treatment within the first month of diabetes incidence. Conversely, if not treated in the first few weeks, most remained untreated throughout the follow-up period. Only 158 patients (13% of treated or 7% of overall patients) received a treatment after initial 16 weeks.

Fig. 1.

Time to initial treatment (in weeks, up to 52 weeks) – Kaplan-Meier cumulative hazard estimates.

Treatment Choices During the First Year of Diabetes Incidence

About half of the patients were treated in the first year of diabetes incidence. A fifth (20%) received medication only, 15% received education/counseling, and 20% both (Table 1). When a patient received both medication and education/counseling (n=447), the treatments were likely to be concurrent (84%). Among those who received medication prescription (n=898), the first choice of medication was Metformin for the vast majority (87%).

Comparison of Treated and Not Treated Patients

There were several significant differences in bivariate analysis between the patients who were treated and untreated in the first year of follow-up (Table 2). Patients who were treated, compared to non-treated, were more likely to be young or obese, have higher levels of fasting blood glucose, triglyceride and LDL cholesterol, and were more likely to have a primary care or endocrinology visit during the first follow-up year (all at P<0.001). The treated were less likely to be female or overweight, to have limited English proficiency and to have made other specialty or urgent care visits only (all at P<0.01).

Table 2.

Comparison of patients with and without a treatment during one year follow-up.

| Variable (unit) | Treatmenta N=1,244 (55%) |

No treatment N=1,014 (45%) |

P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 53.9 [12.2] | 60.6 [15.0] | <0.001 |

| Female | 492 (39.6) | 482 (47.5) | <0.001 |

| Race/ethnicity | 0.062 | ||

| Non-Hispanic white | 661 (53.1) | 527 (52.0) | |

| Asian | 408 (32.8) | 371 (36.6) | |

| Black | 24 (1.9) | 23 (2.3) | |

| Latino | 151 (12.1) | 93 (9.2) | |

| Limited English proficiency | 86 (6.9) | 111 (11.0) | 0.001 |

| Insurance type | 0.159 | ||

| PPO | 743 (59.7) | 640 (63.1) | |

| HMO | 466 (37.5) | 341 (33.6) | |

| Other insurance | 10 (0.8) | 10 (1.0) | |

| Clinical risk factors at baselineb | |||

| Fasting glucose | 166.0 [74.2] mg/dL or 9.2mmol/L | 128.9 [26.6] mg/dL or 7.2mmol/L | <0.001 |

| Glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1C) | 7.9 [2.0]% or 10.0 mmol/L | 6.4 [0.6]% or 7.6 mmol/L | <0.001 |

| Obese | 560 (45.0) | 338 (33.3) | <0.001 |

| Overweight | 333 (26.8) | 337 (33.2) | 0.001 |

| High systolic blood pressure (>=140mmHg) | 283 (22.8) | 244 (24.1) | 0.484 |

| High triglyceride (>=150mg/dL or 1.7mmol/L) | 592 (47.6) | 367 (36.2) | <0.001 |

| High LDL cholesterol (>=130mg/dL or 3.4mmol/L) | 322 (25.9) | 236 (23.3) | 0.083 |

| Service use during first follow up year | |||

| Any primary care visit | 931 (74.8) | 684 (67.5) | <0.001 |

| Any endocrinology visit | 46 (3.7) | 12 (1.2) | <0.001 |

| Specialty or urgent care visit only | 18 (1.5) | 39 (3.9) | <0.001 |

| No clinic visit, 1st follow up year | 291 (23.4) | 289 (28.5) | 0.006 |

For the bivariate comparisons, Fisher’s exact tests were used for dichotomous variables and Chi-squared tests were used for continuous variables.

Any medication prescription or attendance to an education/counseling session.

Fasting glucose: N=2,009 (89.0%); HbA1c: N=1,714 (75.9%); for other clinical indicators (overweight, obese, high systolic blood pressure, high triglyceride and high LDL cholesterol), missing baseline measurement was coded as 0.

Predictors of Treatment for Incident Diabetes

Multivariate analyses results show that the likelihood of getting any treatment decreases with advanced age (Table 3). The relative risk ratio (RRR) of patients age 55–64 as compared to age 35–44 to receive both medication and education/counseling was 0.54 (95%CI=0.35–0.84), and the RRR of patients age 75 or older was only 0.13 (95%CI=0.07–0.25). Patients who have HMO insurance, compared to other insurance, mostly PPO, were more likely to receive education/counseling alone (RRR=1.48; 95%CI=1.12–1.96) or along with medication (RRR=1.43; 95%CI=1.07–1.92). The likelihood of receiving a treatment did not differ based on patient race/ethnicity.

Table 3.

Determinants of treatment within one year of incident diabetes (multinomial logistic physician random effects model).

| Covariates | Medication & education/cou nseling | Medication prescription only | Education/counseling only |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (ref: 35–44) | |||

| Age 45–54 | 0.63* (0.43 – 0.94) | 0.74 (0.51 – 1.08) | 0.72 (0.47 – 1.09) |

| Age 55–64 | 0.54** (0.35 – 0.84) | 0.63* (0.41 – 0.95) | 0.88 (0.57 – 1.35) |

| Age 65–74 | 0.55* (0.33 – 0.91) | 0.37*** (0.22 – 0.63) | 0.90 (0.56 – 1.47) |

| Age 75 or older | 0.13*** (0.070 – 0.25) | 0.19*** (0.11 – 0.34) | 0.38*** (0.22 – 0.66) |

| Female | 1.30 (0.97 – 1.76) | 1.04 (0.78 – 1.39) | 0.79 (0.59 – 1.05) |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| Asian | 1.02 (0.72 – 1.44) | 1.00 (0.72 – 1.39) | 1.07 (0.76 – 1.49) |

| Black | 0.85 (0.30 – 2.35) | 0.76 (0.27 – 2.16) | 0.88 (0.33 – 2.37) |

| Latino | 1.12 (0.70 – 1.78) | 0.97 (0.60 – 1.55) | 1.10 (0.69 – 1.76) |

| Limited English proficiency | 0.92 (0.53 – 1.58) | 1.16 (0.72 – 1.87) | 0.61 (0.34 – 1.07) |

| HMO (ref: PPO or other insurance) | 1.43* (1.07 – 1.92) | 1.04 (0.78 – 1.39) | 1.48** (1.12 – 1.96) |

| Clinical risk factorsa | |||

| Fasting glucose (15mg/dL or 0.8mmol/L)b | 1.48*** (1.40 – 1.57) | 1.38*** (1.30 – 1.46) | 1.08* (1.01 – 1.16) |

| Obese | 1.78** (1.21 – 2.63) | 1.25 (0.86 – 1.80) | 1.66** (1.14 – 2.42) |

| Overweight | 1.01 (0.68 – 1.51) | 0.96 (0.67 – 1.39) | 1.06 (0.73 – 1.54) |

| Systolic blood pressure (10mmHg) | 1.07 (0.76 – 1.48) | 0.95 (0.68 – 1.32) | 0.99 (0.72 – 1.36) |

| Triglyceride (50mg/dL or 0.57mmol/L) | 1.45* (1.08 – 1.95) | 1.23 (0.92 – 1.64) | 1.21 (0.91 – 1.61) |

| LDL cholesterol (20mg/dL or 0.52mmol/L) | 1.17 (0.85 – 1.60) | 1.12 (0.83 – 1.53) | 1.00 (0.73 – 1.37) |

| Service use during the first follow up year (ref: No physician office visit) | |||

| Any primary care visit | 1.13 (0.79 – 1.61) | 1.56* (1.11 – 2.21) | 0.79 (0.57 – 1.09) |

| Any endocrinology visit | 3.55** (1.45 – 8.68) | 1.12 (0.39 – 3.19) | 1.63 (0.56 – 4.71) |

| Other specialty or urgent care visit only | 0.52 (0.19 – 1.47) | 0.37 (0.10 – 1.30) | 0.62 (0.27 – 1.43) |

P < 0.05;

P < 0.01;

P < 0.001.

Relative risk ratios (95% CIs) are presented.

Log likelihood = −2,231; N = 2,009.

Coefficient for physician random intercepts (95% CI) = 1.70***(1.44 – 2.02).

For ease of interpretation, the units of clinical indicators are set to the difference between 25 percentile and median values, as indicated in the parentheses. For example, the coefficient for fasting blood glucose indicates the odds ratio of 15mg/dL or 0.8mmol/L increase in the value.

The overall regression result was similar when HbA1c, instead of fasting blood glucose, was used.

Also included but not presented in the table are indicators of clinic location.

Fasting blood glucose level was the strongest, independent positive predictor for receiving a treatment. For example, a 15 mg/dL (or 0.83mmol/L) increase in the baseline fasting blood glucose was associated with 48% increase in RRR (95%CI=1.40–1.57) to receive both medication and education/counseling, 38% increase in RRR (95%CI=1.30–1.46) to receive medication prescription only. The overall regression results were similar when using HbA1c (not reported), rather than fasting blood glucose. Obesity was a positive predictor of treatment either education/counseling alone (RRR=1.66; 95%CI=1.14–2.42) or along with medication (RRR=1.78; 95%CI=1.21–2.63). Increasing level of triglyceride was also a positive predictor of combined treatment (RRR=1.45; 95%CI=1.08–1.95).

Visit to a primary care physician during the first follow up year, as compared to no physician office visit, was a strong predictor for receiving medication treatment (RRR=1.56; 95%CI=1.11–2.21) but not for education/counseling. Visit to an endocrinologist, on the other hand, increased the RRR to receive combined treatment more than 3-fold (RRR=3.55; 95%CI=1.45–8.68).

DISCUSSION

Despite the known importance of early identification and treatment of diabetes for the prevention of diabetic complications, incident diabetes is suboptimally treated even in a group of insured, active primary care patients. In our study, only half of patients were treated during the first year following diabetes incidence, and only 20% of patients received both medication prescription and lifestyle modification interventions. When treated, treatment often occurred promptly. Almost half of treated patients received their treatment during the first week after diabetes incidence, and thereafter the curve for treatment initiation is relatively flat. When a patient received both medication and lifestyle interventions, the two treatments were concurrent most of time, as guidelines recommend [16]. Given the extensive literature on the benefits and safety of starting both treatments even in the pre-diabetic stage, more emphasis should be placed on earlier treatment initiation [4–7,17,18].

The UCLA-CHAMP program showed that immediate initiation of all effective therapies for secondary prevention of coronary artery disease was more effective than a more conservative outpatient follow-up approach [19]. A similar program for patients with incident diabetes may propose immediate initiation of therapy with education/counseling in conjunction with medication, with appropriate follow-up. More research is needed to assess the specific reasons that patients and providers do not initiate treatment immediately, to inform effective interventions.

The observed suboptimal initial treatment rates may reflect patient preference. As our study cohort consisted of active primary care patients of the health care system, most (74%) patients in this study did see a physician during the first year after diagnosis. Among those patients who were not treated in the first year after diagnosis, 30% made a clinic visit to specifically address their diabetes (as evidenced by a visit diagnosis of diabetes). Two thirds (68%) of patients who were not treated actually came into the clinic to see a physician. All the patients included in the study were active patients of the health care system and were eventually seen in clinic over the subsequent years of follow up (up to 4.5 years after initial diagnosis). Further years of follow up after the first year, however, did not increase treatment rates in these patients (results not reported), confirming that most initial treatment takes place at diagnosis.

Within the first year after diagnosis, patients who saw a primary care physician or endocrinologist were more likely to receive medication and/or education/counseling treatment. Seeing a physician at urgent care or a specialist other than endocrinologist, mainly for reasons other than diabetes, however, did not make a difference in treatment rates, compared to those who did not see a physician. Our findings argue for the need for a team approach for diabetes management. Prompts in the EHR could be included to flag patients with diabetes so that even when unrelated clinic visits are made, follow-up is appropriately pursued.

The organization studied has shown high performance in diabetes management indicators in the state-wide pay-for-performance program [20]. Even in this high resource setting, treatment of initial diabetes seems to be suboptimal. Diabetes registries often use physician diagnosis of diabetes only, and as diabetes in its early stage is often underdiagnosed [21], incident diabetes cases that are not documented tend not to be actively treated. Improved algorithms for identifying diabetes cases using laboratory values (as we have done) now available in EHR, in addition to physician diagnosis (traditionally available in administrative data), may help monitor early initiation of treatment.

Our data indicate that incident diabetes cases are typically managed by primary care providers rather than immediately referred to an endocrinologist (only 2.6% of primary care patients saw an endocrinologist during the first follow-up year). For patients who made a visit to primary care department, particular physician demographic or practice characteristics (e.g., gender, years of practice, panel size, diabetes panel size) did not predict treatment initiation (results not reported). This is consistent with existing evidence showing that majority of new diagnosis of diabetes occurred in primary care setting, and 65% of patients with diabetes in the United Stated are cared for by primary care physicians [22]. The ADA guidelines recommend uncomplicated cases of diabetes to be managed by primary care physicians [16].

The lower treatment rate in older patients is of concern. Clinical guidelines generally recommend less aggressive glycemic control for frail older adults [23,24], although the evidence regarding the recommendation is tenuous because frail older patients are usually excluded from clinical trials [23,24]. On the other hand, in our diverse insured population, race/ethnicity or limited English proficiency was not a significant predictor of treatment, which may suggest that access may underlie some of the racial/ethnic disparities in diabetes treatment reported in the literature [25]. Insurance type did matter in receiving lifestyle interventions, which may be more available to HMO patients who are covered by capitation. The recent trends toward bundled payment or Accountable Care Organization could have a positive influence on providing more comprehensive diabetes treatment.

Several limitations, mostly due to the defined scope of our study, merit discussion. First, adherence to medication was not examined, as we did not have access to prescription dispensing data. Therefore, actual rate of medication use by patients may be lower. On the other hand, education/counseling treatment was based on attendance, which requires both physician referral and patient adherence. Second, some patients who were not treated nor whose diabetes was not actively monitored may have had other serious comorbidities, so onset of diabetes may not have been a priority in their treatment plan. We excluded patients with illnesses that prohibit active diabetes treatment such as cancer, kidney disease and liver disease, but there could be still many other patients whose conditions may preclude active diabetes treatment. Finally, as our study focuses on treatment options in clinical settings, we did not examine patient-initiated lifestyle modifications outside of clinical care realm.

It is important to note that the study is conducted in the US where providers are mostly paid on a fee-for-services basis. Lack of care coordination, in part due to the payment system, may be an important contributor of delayed initiation of diabetes treatment. Many patients (39%) did not make a follow up visit to a primary care provider during the first year of diabetes diagnosis. Furthermore, there are multiple guidelines for diabetes treatment, which often conflict each other. The American Diabetes Association guideline, which is most widely adopted by clinicians, is not strictly enforced by the health care organizations. Treatment cost to patient, however, may not be a large inhibiting factor because all the patients in the study were insured, though co-pays and drug plans likely differed across patients, and we were unable to examine this factor as a predictor of initiation of therapy. Medication and education/counseling treatment, with provider diagnosis, are usually covered by most insurance. The most commonly prescribed diabetes medication, Metformin, is generically available and is very inexpensive (e.g., $4 per two months’ supply), so direct-to-consumer advertising is not likely to have played a large role in prescribing patterns in this study.

CONCLUSIONS

Newly identified diabetes is undertreated, even in a high resource setting where all patients have health insurance and access to care. When treated, treatment occurs soon after diagnosis. If not treated immediately, incident diabetes is rarely infrequently treated after the first few weeks, while patients continue seeking care for other reasons. Team approaches across specialties to monitor patients with incident diabetes, taking advantage of shared EHR system, may facilitate early initiation of diabetes treatment.

Highlights.

We examined patterns of treatment initiation for incident diabetes in an ambulatory care setting in the US.

Diabetes onset and treatment were identified with information from electronic health records (EHR).

Among insured patients who have a primary care provider, incident diabetes is treated only half the time.

Of the treated, 68% received a treatment within the first four weeks, and 13% after initial 16 weeks.

Improved algorithms for identifying incident diabetes from the EHR and team approach for monitoring may help treatment initiation.

Acknowledgments

Funding source

This study was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (1R01DK081371) and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (K01HS019815). The funding sources had no role in the study’s design, conduct or reporting.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest in connection with this article.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Sukyung Chung, Email: chungs@pamfri.org, Palo Alto Medical Foundation Research Institute, Ames Building, 795 El Camino Real, Palo Alto, CA 94301, Ph: 650-853-4763/Fax: 650-329-9114.

Beinan Zhao, Palo Alto Medical Foundation Research Institute, Palo Alto, CA.

Diane Lauderdale, University of Chicago, Department of Health Studies, Chicago, IL.

Randolph Linde, Palo Alto Medical Foundation, Endocrinology Department, Palo Alto, CA.

Randall Stafford, Stanford University, Prevention Research Center, Palo Alto, CA.

Latha Palaniappan, Palo Alto Medical Foundation Research Institute and Stanford University, Prevention Research Center, Palo Alto, CA.

References

- 1.Nathan DM, Buse JB, Davidson MB, et al. Medical management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes: a consensus algorithm for the initiation and adjustment of therapy. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:193–203. doi: 10.2337/dc08-9025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.ADA. Executive summary: Standards of medical care in diabetes--2010. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(Suppl 1):S4–10. doi: 10.2337/dc10-S004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Colagiuri S, Cull CA, Holman RR. Are lower fasting plasma glucose levels at diagnosis of type 2 diabetes associated with improved outcomes? Diabetes Care. 2002;25:1410–1417. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.8.1410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Knowler WC, Fowler SE, Hamman RF, et al. 10-year follow-up of diabetes incidence and weight loss in the Diabetes Prevention Program Outcomes Study. Lancet. 2009;374:1677–1686. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61457-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE, et al. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:393–403. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pan XR, Li GW, Hu YH, et al. Effects of diet and exercise in preventing NIDDM in people with impaired glucose tolerance. The Da Qing IGT and Diabetes Study. Diabetes Care. 1997;20:537–544. doi: 10.2337/diacare.20.4.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li G, Zhang P, Wang J, et al. The long-term effect of lifestyle interventions to prevent diabetes in the China Da Qing Diabetes Prevention Study: a 20-year follow-up study. Lancet. 2008;371:1783–1789. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60766-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Espeland M. Reduction in weight and cardiovascular disease risk factors in individuals with type 2 diabetes: one-year results of the Look AHEAD trial. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:1374–1383. doi: 10.2337/dc07-0048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Malik S, Lopez V, Chen R, et al. Undertreatment of cardiovascular risk factors among persons with diabetes in the United States. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2007;77:126–133. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2006.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jacobs MJ, Kleisli T, Pio JR, et al. Prevalence and control of dyslipidemia among persons with diabetes in the United States. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2005;70:263–269. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2005.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hunt KJ, Gebregziabher M, Egede LE. Racial and ethnic differences in cardio-metabolic risk in individuals with undiagnosed diabetes: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1999–2008. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27:893–900. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2023-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schmittdiel JA, Uratsu CS, Karter AJ, et al. Why don’t diabetes patients achieve recommended risk factor targets? Poor adherence versus lack of treatment intensification. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:588–594. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0554-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Horn SD, Gassaway J. Practice-based evidence study design for comparative effectiveness research. Med Care. 2007;45:S50–S57. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318070c07b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Westfall JM, Mold J, Fagnan L. Practice-based research--“Blue Highways” on the NIH roadmap. JAMA. 2007;297:403–406. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.4.403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.US Census Bureau. Profile of General Demographic Characteristics: 2000 Census Summary File 2, 100-percent data. 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 16.ADA. Standards of medical care in diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2005;28(Suppl 1):S4–S36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ramachandran A, Snehalatha C, Mary S, et al. The Indian Diabetes Prevention Programme shows that lifestyle modification and metformin prevent type 2 diabetes in Asian Indian subjects with impaired glucose tolerance (IDPP-1) Diabetologia. 2006;49:289–297. doi: 10.1007/s00125-005-0097-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tuomilehto J, Lindstrom J, Eriksson JG, et al. Prevention of type 2 diabetes mellitus by changes in lifestyle among subjects with impaired glucose tolerance. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1343–1350. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200105033441801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fonarow GC, Gawlinski A, Moughrabi S, Tillisch JH. Improved treatment of coronary heart disease by implementation of a Cardiac Hospitalization Atherosclerosis Management Program (CHAMP) Am J Cardiol. 2001;87:819–822. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(00)01519-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.IHA. [Accessed November 27, 2013];Pay for Performance-Manuals and Program Operations. 2011 http://www.iha.org/manuals_operations.html.

- 21.Stone MA, Camosso-Stefinovic J, Wilkinson J, et al. Incorrect and incomplete coding and classification of diabetes: a systematic review. Diabetic Med. 2010;27:491–497. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2009.02920.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schappert SMRE. Ambulatory Medical Care Utilization Estimates for 2007. National Center for Health Statistics; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brown AF, Mangione CM, Saliba D, Sarkisian CA. Guidelines for improving the care of the older person with diabetes mellitus. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(5 Suppl Guidelines):S265–S280. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.51.5s.1.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee SJ, Eng C. Goals of glycemic control in frail older patients with diabetes. JAMA. 2011;305:1350–1351. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heisler M, Smith DM, Hayward RA, et al. Racial disparities in diabetes care processes, outcomes, and treatment intensity. Med Care. 2003;41:1221–1232. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000093421.64618.9C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]