Abstract

Aims: To understand current awareness of, and views on, treatment of alcohol dependence in Japan. Methods: (a) Nationwide internet-based survey of 520 individuals, consisting of 52 diagnosed alcohol-dependent (AD) persons, 154 potentially alcohol-dependent (ADP) persons, 104 family members and 106 friends/colleagues of AD persons, and 104 general individuals, derived from a consumer panel where the response rate was 64.3%. We enquired into awareness about the treatment of alcohol dependence and patient pathways through the healthcare network. (b) Nationwide internet-based survey of physicians (response rate 10.1% (2395/23,695) to ask 200 physicians about their management of alcohol use disorders). Results: We deduced that 10% of alcohol-dependent Japanese persons had ever been diagnosed with alcohol dependence, with only 3% ever treated. Regarding putative treatment goals, 20–25% of the AD and ADP persons would prefer to attempt to abstain, while 60–75% preferred ‘reduced drinking.’ A half of the responding physicians considered abstinence as the primary treatment goal in alcohol dependence, while 76% considered reduced drinking as an acceptable goal. Conclusion: AD and ADP persons in Japan have low ‘disease awareness’ defined as ‘understanding of signs, symptoms and consequences of alcohol use disorders,’ which is in line with the overseas situation. The Japanese drinking culture and stigma toward alcohol dependence may contribute to such low disease awareness and current challenging treatment environment. While abstinence remains the preferred treatment goal among physicians, reduced drinking seems to be an acceptable alternative treatment goal to many persons and physicians in Japan.

INTRODUCTION

Alcohol dependence (AD) causes health, social and economic harms for persons, their families and society overall. Alcohol-dependent persons suffer from several co-morbidities such as hepatic dysfunction, pancreatitis, cardiomyopathy, osteoporosis, cerebral atrophy, cognitive dysfunction and peripheral neuropathy, and many of them seek treatment only for these diseases (Higuchi and Saito, 2013). It leads to increased medical costs, decreased productivity, traffic and other accidents and domestic violence (Sekii et al., 2005; White Paper on Alcohol, 2011).

A 2003 national survey in Japan found that the prevalence of alcohol dependence according to ICD-10 criteria was 1.9% in men and 0.1% in women, further explaining that these estimates could vary from 0.6 to 5.1% (0.8–4.4 million), depending on the methodology and criteria used by different authors (Osaki et al., 2005). According to the Kurihama Alcoholism Screening Test (KAST) in 1984 estimated 3.36 million alcohol-dependent patients in Japan (Osaki et al., 2005).

Alcohol dependence in Japan may be partially attributable to the Japanese drinking culture, which is characterized by a high social tolerance for drinking alcohol reflected in the widespread belief in Japan that drinking facilitates socialization and mutual understanding between individuals (Shimizu et al., 2004). On the other hand, in Japan, stigma or negative perceptions about alcohol-dependent persons are relatively high, and stereotypes such as ‘persons with weak will’ or ‘drifters from the society’, might deter such individuals from seeking treatment (Noguchi, 1996).

A local questionnaire survey conducted in Japan in 2003 revealed that 70.6% of the surveyed heavy drinkers (defined as those individuals drinking alcohol >3 days per week and >60 g of alcohol per day—International Guide for Monitoring Alcohol Consumption and Related Harm, 2000) were unaware of their problematic drinking behavior, compared with 41.2% in non-heavy drinkers (Kumagai et al., 2004). The survey found that half of the heavy drinkers were taking no annual health examination, and 54.5% of them were self-employed or worked in the agricultural and fisheries industries. The same study also found that 72% of the heavy drinkers who underwent an annual health examination considered that abstinence or reduced drinking was necessary to improve their health status.

However, other surveys indicate that only ∼5.4% of alcohol-dependent persons in Japan actually seek medical advice regarding their alcohol dependence (White Paper on Alcohol, 2011). A study showed that it took as long as 7.4 years on average for alcohol-dependent persons to visit specialized physicians after their initial visit to non-specialized physicians (Hirofuji et al., 2005).

A long-standing standard treatment goal for alcohol dependence is the achievement of abstinence and support of its maintenance in combination with psychosocial therapy and pharmacotherapy (Higuchi and Saito, 2013). A 2005 nationwide questionnaire involving 5005 psychiatric facilities across Japan reported that group therapy and education programs were the most common psychosocial treatment programs offered to inpatients and outpatients with alcohol dependence (Kochi et al., 2007). As for pharmacotherapy, only disulfiram and cyanamide had been available in Japan until the recent approval of acamprosate in 2013.

In order to expand knowledge regarding the Japanese population's awareness about alcohol dependence, we conducted a survey in adults with alcohol use disorders and their families, and in the general population. We also surveyed attitudes about treatment, and treatment pathways through the healthcare system, among physicians providing care to individuals with alcohol use disorders across Japan. The surveys also explored the attitudes and preferences of individuals and physicians toward ‘reduced drinking’ as an alternative to abstinence as a treatment goal, following reports of an increasing awareness of ‘harm reduction’ as a legitimate goal among alcohol dependence specialists in Japan (Hirofuji et al., 2005).

METHODS

General population survey: views of alcohol-dependent persons, family, friends/colleagues and others

An internet survey of 52,176 individuals (commercially owned ‘INTAGE Consumer Panel’), considered representative of the Japanese population of 2010, was conducted from 22 to 27 February 2012, reaching a geographically dispersed population. From this, we have excluded people not employed for 6 months or more (at the time of the survey) in order to exclude a population with a higher level of social disability. People aged 70 years or older were excluded to eliminate bias by computer literacy. People under 20 years old were also excluded because 20 is the legal drinking age in Japan. In addition 350 responses were excluded due to incomplete or repeated answers, leaving 51,826 valid responses. In these responses we found 591 alcohol-dependent (AD) persons and 3255 potentially alcohol-dependent (ADP) persons based on the screening criteria described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Screening criteria for classification of alcohol-dependent patients and potential patients

| Group | n | AUDIT total score (max 40) | Dependence score (Q4 + Q5 + Q6) | Diagnosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Alcohol-dependent patients (AD) | 52 | All scores | All scores | Yes |

| 2 Potential patients (ADP) | ||||

| Dependent | High AUDIT 52 | 20 or more | 4 or more | No |

| Low AUDIT 50 | 16–19 | 4 or more | ||

| Non-dependent | High AUDIT 26 | 20 or more | Below 4 | No |

| Low AUDIT 26 | 16–19 | Below 4 |

Q4: What is ‘drinking’ to you? (single choice per several items).

Q5: How do you feel about your own drinking habits? (single choice from five response scales).

Q6: How do your family members and friends feel about your drinking habits? (single choice from five response scales).

From the subset so identified, a main survey was conducted. We sent a questionnaire to 919 individuals and collected 591 valid responses (response rate of 64.3%). Due to the contract of 520 cases agreed with the analyzing company a further 71 cases were excluded at random. This gave 52 who reportedly had been diagnosed by a physician as alcohol dependent and 154 individuals who screened as potentially alcohol dependent (ADP) on the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test or AUDIT (Second Edition, self-reported version). We further categorized these ADP persons into four groups as shown in Table 1.

There were 104 ‘family members’ of AD persons (identified as stating that they were living or had lived with close relatives—parents, grand-parents, siblings, partners or children—diagnosed with alcohol dependence. There were 106 individuals identified as ‘friends/colleagues’ of AD persons who reported that they had one or more ‘close friends/colleagues’ diagnosed with alcohol dependence. The remaining 104 respondents met neither the criteria for ‘family members’ nor ‘friends/colleagues’ of AD persons and were termed as ‘general population’.

We then conducted a follow-up survey among 142 AD persons (30 from the original survey sample and 112 from the screened survey sample who were willing to answer additional questions) and investigated their perception of patient pathways through the healthcare network and current treatment made available in Japan.

The original survey contained 29 questions concerning motivation for drinking, awareness of alcohol use disorders, perception of excessive drinking and alcohol dependence, and evaluation of the concept of reduced drinking. The follow-up survey contained 19 questions concerning the pathway and treatment for AD persons. The answers were collected through multiple choice answers, scales answers, and short open-ended answers which were later coded for a quantitative analysis. The respondents received no incentives for completing and submitting their answers, and no personal information was provided (management of sample through the panel owned by a third party vendor).

Results for the AD and ADP sample

Screening questions and the results of alcohol consumption level among AD, ADP and general population (AUDIT questions one unit = 10 g of alcohol) are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Screening questions and results of alcohol consumption level (one unit: 10 g of alcohol based on the AUDIT questions)

| General subjects | AD | ADP | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Drinking frequency | |||

| Do they drink alcohol? | Yes 76% | Yes 55% | Yes 100% |

| Do they drink alcohol 4 or more times a week? | Yes 23% | Yes 28% | Yes 82% |

| Alcohol drinkers | |||

| Amount of drinking on a typical day | |||

| How many drinks do they have on a typical day when they have drink? | 14% drink | 31% drink | 68% drink |

| 5 drinks or more | 5 drinks or more | 5 drinks or more | |

| What is the average unit of drinks? | 3.5 units | 5.0 units | 12.2 units |

| Frequency of over-drinking | |||

| How often do you have over-drinking? | 3% over-drink daily or almost daily | 23% over-drink daily or almost daily | 41% over-drink daily or almost daily |

| Self-control of drinking | |||

| Have you found that you were not able to stop drinking? | Yes 14% | Yes 52% | Yes 86% |

| Other drinking behavior | |||

| Have you failed to do what was normally expected because of drinking? | Yes 17% | Yes 46% | Yes 79% |

| Have you needed a first drink in the morning to get yourself going after a heavy drinking session? | Yes 3% | Yes 34% | Yes 32% |

| Have you had a feeling of guilt or remorse after drinking? | Yes 15% | Yes 46% | Yes 75% |

| Have you been unable to remember what happened the night before because you had been drinking? | Yes 14% | Yes 44% | Yes 82% |

Physician survey: method

We conducted a qualitative pilot interview from 29 March to 4 April 2012 with six alcohol use disorders specialists, to evaluate the validity and appropriateness of the questionnaire to be used for the survey. A panel constituted by 130,000 (50%) of Japanese physicians (M3 ‘Research-kun’), including up to 6000 psychiatrists was used. The response rate to our internet invitation was 10.1% (2395/23,695) among whom we conducted a quantitative survey from 20 to 26 April 2012 with 200 physicians who reported treating >20 alcohol use disorder patients every year, to ask about their perception of current clinical management of alcohol use disorders in Japan. The survey included 65 questions regarding patient typology, types of care administered, and treatment goals. The answers were collected through multiple choice answers, scale answers and short open-ended answers, which were later coded for a quantitative analysis. The respondents received no incentives for completing and submitting their answers, and no personal information was provided (management of sample through the panel owned by a third party vendor).

RESULTS

Persons, family, friends/colleagues and general population survey

The average age of the respondents was 46 ± 0.5 years, with an even gender distribution. Approximately 60% of the respondents were confirmed to be working.

In AD and ADP persons, the most common reasons for beginning to drink on a daily basis were ‘need for relaxation and rest’ (31 and 49%, respectively), ‘to have fun’ (25 and 37%, respectively) and ‘to achieve relief from stress in private life’ (22 and 25%, respectively). Similarly, the most common reasons for excessive drinking were ‘need for relaxation and rest’ (16 and 18%, respectively), ‘to have fun’ (9 and 26%, respectively) and ‘to achieve relief from stress in private life’ (16 and 23%, respectively).

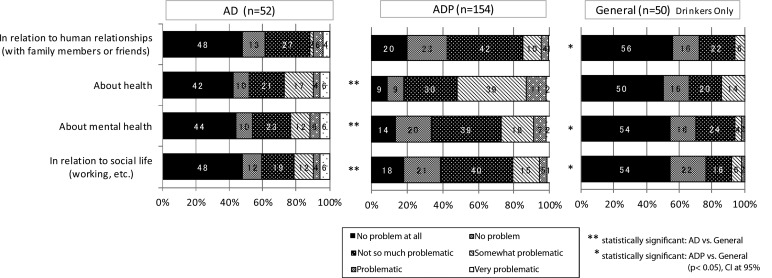

Self-awareness of drinking by the AD and ADP persons, and general population (drinkers only) are described in Fig. 1, as answers to the question, ‘How problematic do you think your drinking is in each of the following situations in daily life?’ A non-significant trend was found showing that ADP persons were more concerned than AD persons about the effects of drinking on their health, mental health, social life and relationships with their family and friends/colleagues. Compared with the general population, AD persons were more concerned about their physical health, and ADP persons were more concerned about their human relationships (family and friends/colleagues) with significant difference (P < 0.05).

Fig. 1.

Answer to the question ‘How problematic do you think your drinking is in each of the following situations in daily life?’

We found that 77% of AD persons and 68% of ADP persons who were aware of their alcohol-related problems were reluctant to seek medical care. Only 8% of AD persons reported that they had had treatment for alcohol dependence: the most common reasons for AD persons to visit a hospital or clinic were the following: ‘family members suggested’ (71%), ‘friends/colleagues suggested’ (57%), ‘had health problems’ (57%), ‘had problems with human relationships’ (29%) and ‘physician's intervention’ (29%). Interestingly, 57% of the AD persons and 34% of the ADP persons responded that they had never or almost never thought about drinking less or abstaining. The follow-up survey showed that diagnosed but untreated AD persons' disease awareness was lower (14.3%) than that of treated AD persons (65.8%).

Like the AD persons, the AD persons' family and friends/colleagues as well as the ‘general population’ subjects were more concerned about the effect of excessive drinking on the physical health than on the mental health, relationships with family and friends/colleagues, and social life.

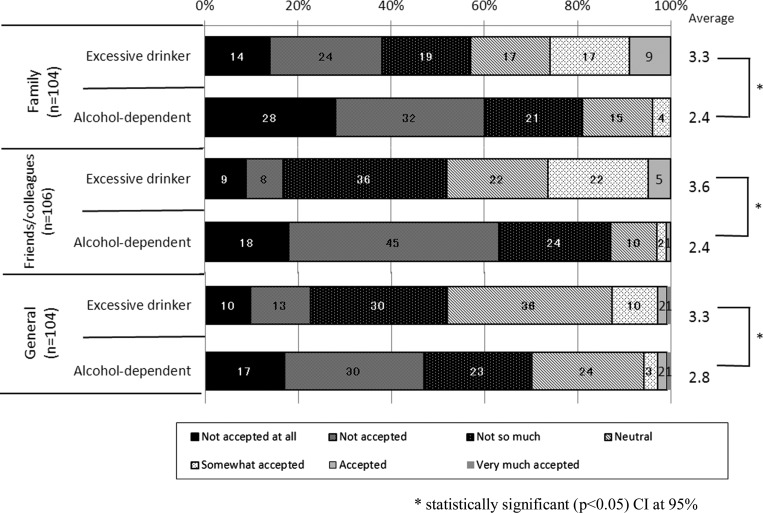

Attitudes regarding the social acceptance of excessive drinkers and alcohol-dependent persons are described in Fig. 2. In these three groups, 70–80% of the respondents answered that alcohol-dependent patients were not socially acceptable, significantly different (P < 0.05) from the same respondents' social acceptability rating of excessive drinkers.

Fig. 2.

Social acceptability of excessive drinkers and alcohol-dependent patients.

The AD persons' family and friends/colleagues were asked to choose their image of alcohol-dependent patients. Our results also showed that alcohol-dependent persons were frequently associated by their family and friends/colleagues with the following attributes: daily drinking (78 and 77%, respectively), become violent when drinking (69 and 57%, respectively), have family problems (52 and 59%, respectively), have mental or physical illness (69 and 78%, respectively) and have mental weakness (64 and 69%, respectively). On the other hand, excessive drinkers were less associated by their family and friends/colleagues with the following attributes in particular: have mental or physical illness (25 and 29%, respectively) and have mental weakness (42 and 24%, respectively).

The results from the follow-up survey indicated that the most common reason why AD persons did not receive treatment after being diagnosed was that they ‘did not think treatment was necessary’.

Family members were asked if they took any action when they recognized the AD persons' problematic drinking behavior: 74% answered they took some actions. For example, 48% recommended the patients to seek medical advice; 39% talked to the patients about their drinking problem; and 36% consulted with another person. Similar attempts were made by 58% respondents from the ‘friends/colleagues’ group.

Physician survey: results

According to the physician survey, the number of alcohol use disorder patients treated by this sample per year was ∼14,470 patients of whom the physicians estimated that around three-quarters would be male, 80% were 40 years or older, 34% would have lost jobs due to drinking or lived on public assistance and 48% would live alone. We asked the number of alcohol use disorder patients seen during the past year, and if the physicians had seen >20, we further asked how many of those patients had been diagnosed as alcohol-dependent persons. The results indicated that 72% (52.1/72.4) of alcohol use disorder persons who visited physicians per year had received a diagnosis of alcohol dependence. A greater proportion of those treated by psychiatrists would have been diagnosed dependent (93%), compared with the diagnoses made by internists, gastroenterologists and cardiologists (41, 50 and 32%, respectively). These physicians estimated that the rate of receiving a correct diagnosis of alcohol dependence, rate of receiving treatment and the rate of continuing treatment 50, 3 and 0.9%, respectively.

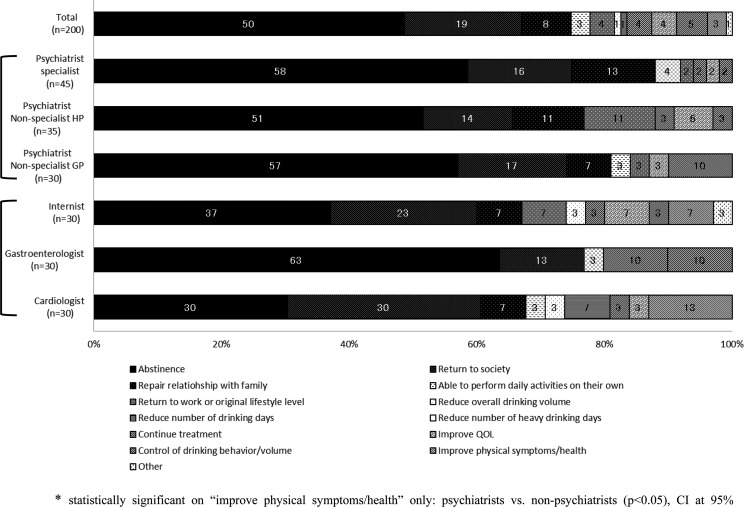

The main results regarding the treatment goals considered by the physicians who responded as the most important are shown in Fig. 3, and the most important factors to consider when establishing a treatment goal for the individual patient are described in Table 3.

Fig. 3.

Treatment goals considered by physicians as most important.

Table 3.

Most important factors to consider when setting a treatment goal for the individual patient (open answer)

| Total | Psychiatrists specialist | Psychiatrists Non-specialist HP | Psychiatrists Non-specialist GP | Internist | Gastroenterologists | Cardiologists | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 136 | n = 29 | n = 26 | n = 23 | n = 17 | n = 18 | n = 23 | |

| Patient background/living environment (net) | 40 (29%) | 9 (31%) | 7 (27%) | 7 (30%) | 6 (35%) | 6 (33%) | 5 (22%) |

| Presence of family | 15 (11%) | 7 (24%) | 2 (8%) | 2 (9%) | 3 (18%) | 1 (6%) | 0 (0%) |

| Necessity of returning to society or work | 14 (10%) | 2 (7%) | 4 (15%) | 3 (13%) | 1 (6%) | 1 (6%) | 3 (13%) |

| Patient background/living environment | 9 (7%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (9%) | 2 (12%) | 4 (22%) | 1 (4%) |

| Economic conditions/standard of living | 4 (3%) | 1 (3%) | 1 (4%) | 1 (4%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (4%) |

| Has a job or not | 2 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (4%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (6%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Can achieve abstinence or not | 17 (13%) | 3 (10%) | 4 (15%) | 3 (13%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (22%) | 3 (13%) |

| Willing to recover or not | 16 (12%) | 1 (3%) | 3 (12%) | 2 (9%) | 3 (18%) | 3 (17%) | 4 (17%) |

| Can reduce alcohol consumption or not | 11 (8%) | 4 (14%) | 3 (12%) | 2 (9%) | 2 (12%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Age | 10 (7%) | 4 (14%) | 3 (12%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (6%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (9%) |

| Presence of any mental illness | 7 (5%) | 2 (7%) | 1 (4%) | 2 (9%) | 1 (6%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (4%) |

| Presence of any co-morbidities | 7 (5%) | 4 (14%) | 2 (8%) | 1 (4%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Personality | 5 (4%) | 2 (7%) | 1 (4%) | 1 (4%) | 1 (6%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Availability of family support | 6 (4%) | 2 (7%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (4%) | 2 (12%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (4%) |

| Presence and severity of dementia/ability to understand | 6 (4%) | 1 (3%) | 2 (8%) | 1 (4%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (6%) | 1 (4%) |

| Diagnosis of alcohol dependence | 5 (4%) | 1 (3%) | 2 (8%) | 1 (4%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (4%) |

| Severity of alcohol use disorders (net) | 6 (4%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (4%) | 3 (13%) | 1 (6%) | 1 (6%) | 0 (0%) |

| General condition/physical condition | 4 (3%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (4%) | 2 (9%) | 1 (6%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Severity of alcohol use disorders | 3 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (4%) | 1 (4%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (6%) | 0 (0%) |

| Gender | 4 (3%) | 3 (10%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (4%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Case by case | 4 (3%) | 2 (7%) | 1 (4%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (6%) | 0 (0%) |

| Recurrent alcohol use disorders or not | 1 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (4%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Acute alcohol use disorders or not | 2 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (9%) |

| Others | 13 (10%) | 1 (3%) | 2 (8%) | 3 (13%) | 1 (6%) | 2 (11%) | 4 (17%) |

| Unknown/uncertain | 9 (7%) | 2 (7%) | 3 (12%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (12%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (9%) |

Units: number of physicians (%).

Although all the physicians types (gastroenterologists in particular) considered abstinence as the most important treatment goal, internists placed higher importance than other physicians on improving Quality of Life and ability to perform daily activities, while gastroenterologists put more attention in controlling drinking behaviors/volume and continuing the treatment, as shown in Fig. 3. Furthermore, non-psychiatrists (internists, gastroenterologists and cardiologists) placed a higher importance on improving physical health than psychiatrists (P < 0.05).

In the physician survey, the 68% who answered that ‘the treatment goal depends on the characteristics of patients’ were further questioned about ‘the most important factors to consider when setting a treatment goal for the individual patient.’ The factors more frequently mentioned were ‘the patient's ability to achieve abstinence or reduce alcohol consumption’, ‘willingness to recover’ and ‘need to return to society or work’, as shown in Table 3.

Furthermore, >75% of physicians responded that pharmacotherapy that helps to achieve a controlled drinking would be useful for those who cannot abstain or repeatedly fail to maintain abstinence.

There was a question about ‘the main problems with current patient management.’ Approximately 80% of the responding physicians pointed out a low consultation rate (which they had presorted as 22%), low treatment continuation rate (previously estimated as 0.9%) and lack of alcohol-dependent patients' disease awareness. To resolve these issues, the necessity of patient and public education was raised by one-third of all the physicians. Moreover, physicians' training on alcohol use disorders, improved treatment facilities such as specialized outpatient units and expanded hospital capacity, and increased support from the patients' family and society were mentioned.

DISCUSSION

The results of our survey indicated that awareness in Japan of alcohol use disorders was low, and it was associated with stigma around the diagnosis and disease of alcohol dependence. Family members and friends/colleagues of AD persons had a negative perception regarding persons diagnosed as alcohol dependent but not necessarily toward the individuals or non-diagnosed patients that exhibit an excessive alcohol consumption behavior. Although stigma toward alcohol dependence is a common issue among many countries (International Guide for Monitoring Alcohol Consumption and Related Harm, 2000), this highly stigmatized perception particularly toward the ‘diagnosis’ of alcohol dependence in contrast to a rather tolerant behavior toward the ‘excessive drinking pattern’ is considered to be one of the reasons for low consultation and treatment rates particularly in Japan, discouraging an open discussion about alcohol dependence.

Moreover, the survey indicated that the provision of correct diagnosis of alcohol dependence and the range of treatment are affected by the types of physicians and the patients' symptoms presented at the initial visit, thus many physicians face a challenging environment to treat and manage alcohol use disorder patients. Perhaps this contributes to some alcohol-dependent patients remaining untreated or treated only after the progression of their disorder.

We have tried to evaluate the acceptability of reduced drinking as a midterm or alternative treatment goal to abstinence. The majority of physicians, as well as AD and ADP persons, were positive toward the concept. Interestingly, AD persons' families showed an even more positive perception of reduction as a treatment goal than AD persons. Given the fact that the patients and their family were most concerned about the negative impact of alcohol consumption on the patients' physical health, it is suggested that reduced drinking in terms of volume and frequency could be an acceptable option for some of these patients.

ADP persons were more concerned than AD persons about their relationships with family and friends/colleagues, mental health, and social life (P < 0.05) as shown in Fig. 1. The reasons for this difference have not been researched in this survey and further research may be necessary. However, it could be hypothesized that AD persons may no longer have a social circle thus care less about their human relationships although they may be more severely impaired physically because of their drinking.

In addition to the major self-help group of alcohol-dependent patients in Japan (Danshukai), educational and support programs for the patients and the general public are further needed for increased understanding and better treatment of alcohol use disorders.

In Japan, currently available medications for alcohol dependence are approved for maintaining abstinence. Our study indicated that 77% of AD and 68% of ADP persons were reluctant to seek medical care: this may be related to a requirement sometimes for an initial hospitalization, which would seem too restrictive to some patients, but also perhaps due to the exclusive focus on achieving and maintaining abstinence as only currently available treatment goal.

Awareness among physicians regarding the achievement of ‘harm reduction’ in alcohol-dependent patients has been increasing, and an improvement of hepatic dysfunction and glucose-lipid metabolism, which can be achieved by reduction of alcohol consumption, has been reported to be an important objective in the treatment of patients with alcoholic liver diseases (White Paper on Alcohol, 2011). There is a correlation between alcohol-related harm and alcohol consumption, and the risk of developing health problems improves when alcohol consumption drops below a certain threshold (Fujita et al., 2013; Rehm and Roerecke 2013). Thus, alcohol reduction is a relevant treatment goal for patients suffering from alcohol dependence, even if abstinence cannot be achieved. Additionally, alcohol reduction provides a new and effective treatment alternative that can be used to treat patients in an earlier stage of their disease, by all types of physicians including primary care physicians. This is particularly important because it seems that most of the so-called ‘hidden patients’ suffering from alcohol dependence have their first contacts in the health care network in Japan through visits of non-specialists. An increase of treatment options as well as alternative treatment goals for alcohol dependence may thus contribute to the reduction of the burden of disease attributable to alcohol dependence in Japan.

In the ADP persons, the ratio of company employees was higher than other groups. Considering that our findings were based on the responses only from the working population, the number of patients reluctant to seek medical care might have been overestimated, because the working population is often too busy to seek medical treatment and being diagnosed with alcohol dependence then required to stop drinking will negatively impact on their employment and social drinking, which is relatively unique to Japan. Further research comparing working population and non-working population may provide a new finding on the awareness and management of alcohol dependence in Japan. Furthermore, it would be interesting to analyze awareness and motivations for seeking treatment and changing drinking behaviors among the different groups of ADP persons in a future study.

CONCLUSIONS

The results of our survey support previous impressions of a large number of undiagnosed persons with alcohol dependence in Japan. There appear also to be low rates of seeking treatment which in part reflects a low awareness that heavy drinking may cause harms, and because of the stigmatization of alcohol dependence in Japanese society. There may also be a low rate of early detection by health care workers. Earlier detection and intervention might help to reduce the disease burden attributable to alcohol dependence in Japan.

Although abstinence is considered the standard treatment goal of alcohol dependence, reduced drinking may serve as an alternative or midterm treatment goal for some individuals suffering from alcohol dependence.

Funding

Funding to pay the Open Access publication charges for this article was provided by Lundbeck Japan.

Conflict of interest statement

The sponsor (Lundbeck) was involved in the study design, data collection, data analysis and interpretation of the data and in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. The corresponding author had full access to all study data and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication. Professor Takei has received honoraria from Lundbeck.

REFERENCES

- Fujita N, Iwasa M, Cho T, et al. Effects of alcohol reduction in patients with alcoholic liver disease. Nihon Arukoru Yakubutsu Igakkai Zasshi. 2013;48:32–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higuchi S, Saito T. Reduction in alcohol consumption: therapeutic goal in alcohol dependence treatment. Nihon Arukoru Yakubutsu Igakkai Zasshi. 2013;48:17–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirofuji H, Ino A, Watanabe S, et al. Present and future situations of support systems for the treatment of alcohol dependence. Nihon Arukoru Yakubutsu Igakkai Zasshi. 2005;40:144–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Guide for Monitoring Alcohol Consumption and Related Harm. Geneva: World Health Organization (WHO); 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Kochi Y, Fukushima H, Suwaki H, et al. Physiopathology of alcoholism and present status of the therapy in Japan–result of the questionnaires sent to all psychiatric care facilities. Seishin Shinkeigaku Zasshi. 2007;109:541–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumagai Y, Morioka I, Yura S, et al. Actual conditions of heavy drinkers in a community and measures against alcoholic problems. Nihon Arukoru Yakubutsu Igakkai Zasshi. 2004;39:180–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noguchi Y. Sociology of Alcoholism. Tokyo, Japan: Nippon Hyoron Sha; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Osaki Y, Matsushita S, Shirasaka T, et al. Nationwide survey of alcohol drinking and alcoholism among Japanese adults. Nihon Arukoru Yakubutsu Igakkai Zasshi. 2005;40:455–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehm J, Roerecke M. Reduction of drinking in problem drinkers and all-cause mortality. Alcohol Alcohol. 2013;48:509–13. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agt021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekii T, Shimizu S, So T. Drinking and domestic violence: findings from clinical survey of alcoholics. Nihon Arukoru Yakubutsu Igakkai Zasshi. 2005;40:95–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu S, Kim D.S., Hirota M. Drinking practice and alcohol-related problems: the National Representative Sample Survey for Healthy Japan 21. Nihon Arukoru Yakubutsu Igakkai Zasshi. 2004;39:189–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White Paper on Alcohol. 2011. Japan (a simplified version available only in Japanese): Japan Society of Alcohol-related Problems Japan Society of Alcohol-related Problems, Japanese Medical Society of Alcohol and Drug Studies, Japanese Society of Biological Psychiatry (eds)