Abstract

Mycobacterium fortuitum is a ubiquitous, rapidly growing nontuberculous mycobacterium (NTM). It is the most commonly reported NTM in peritoneal dialysis (PD) associated peritonitis. We report a case of a 52-year-old man on PD, who developed refractory polymicrobial peritonitis necessitating PD catheter removal and shift to hemodialysis. Thereafter, M. fortuitum was identified in the PD catheter culture and in successive cultures of initial peritoneal effluent and patient was treated with amikacin and ciprofloxacin for six months with a good and sustained clinical response. Months after completion of the course of antibiotics, the patient successfully returned to PD. To our knowledge, this is the first reported case of M. fortuitum peritonitis in the field of polymicrobial PD peritonitis. It demonstrates the diagnostic yield of pursuing further investigations in cases of refractory PD peritonitis. In a systematic review of the literature, only 20 reports of M. fortuitum PD peritonitis were identified. Similar to our case, a delay in microbiological diagnosis was frequently noted and the Tenckhoff catheter was commonly removed. However, the type and duration of antibiotic therapy varied widely making the optimal treatment unclear.

1. Introduction

Bacterial peritonitis is the most common complication of peritoneal dialysis (PD) and often the reason for discontinuing this modality of renal replacement therapy. The vast majority of PD associated peritonitis cases are caused by aerobic bacteria, such as coagulase-negative staphylococci, Staphylococcus aureus, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Culture-negative peritonitis accounts for up to 30% of peritonitis cases [1]. Potential pathogens for this “culture-negative” peritonitis include mycobacteria and fungi. Failure to consider mycobacterial infection in the differential diagnosis of peritonitis may lead to delayed diagnosis and treatment, even to failure of PD. We describe the first case of NTM PD peritonitis caused by Mycobacterium fortuitum (M. fortuitum) in the field of polymicrobial PD peritonitis and a brief literature review concerning M. fortuitum peritonitis in PD patients.

2. Case Presentation

A 52-year-old male patient with hypertension, diabetes, and end-stage renal disease due to diabetic nephropathy had been treated with automated peritoneal dialysis for 2 years without complications. He reported adherence to his aseptic technique and had no previous history of peritonitis.

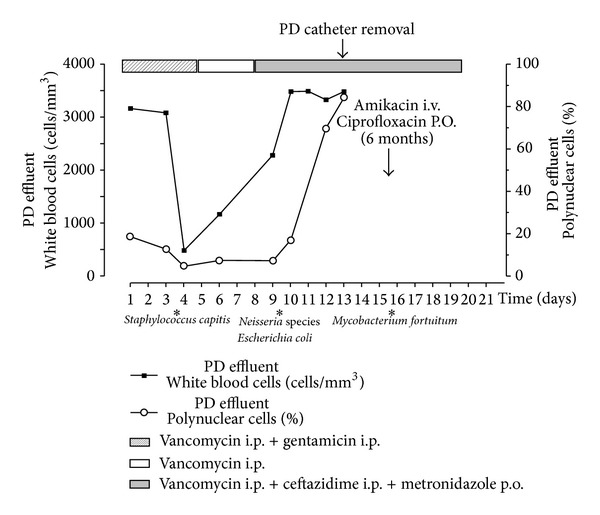

In March 2012, he presented with abdominal pain and turbid peritoneal fluid. Upon admission, the patient had a blood pressure of 120/80 mmHg and showed no signs of fever. Physical examination revealed soft abdomen with crust formation and erythema surrounding the exit site and no signs of catheter tunnel infection. Analyses of the peritoneal fluid demonstrated 740 white blood cells (WBC)/mm3 (predominantly polymorphonuclear neutrophils) (Figure 1). The peritoneal effluent cultures were negative and the exit site swab culture grew Staphylococcus capitis. The patient was empirically treated with intraperitoneal vancomycin and gentamicin. According to the bacterial sensitivity of S. capitis, gentamicin was stopped after 5 days and the patient was discharged from the hospital on intermittent intraperitoneal vancomycin treatment (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Time course of antibiotherapy and PD effluent parameters.

Few days later, the patient was readmitted for persisting abdominal pain. He had fever; his arterial blood pressure was 130/80 mmHg with a heart rate of 85 beats/minute. Physical examination revealed mild abdominal distension with right iliac fossa tenderness to palpation; bowel sounds were present. Tenckhoff catheter exit site showed mild erythema. Abdominal CT scan demonstrated the PD catheter tip resting against the pelvic wall and the colon with inflamed fat and bowel wall thickening (Figure 2). The peritoneal fluid remained turbid (2200 WBC/mm3). The peripheral leukocyte count was 10.700/mm3, with a normal differential. The patient was put on ceftazidime and metronidazole in addition to vancomycin (i.p.). Dialysate culture grew Escherichia coli, Neisseria spp. Following treatment guidelines of refractory peritonitis and considering the risk of bowel perforation, the peritoneal catheter was surgically removed. One day later, the patient's temperature returned to normal and hemodialysis was started. The culture of the PD catheter and successive cultures of the initial peritoneal effluent grew M. fortuitum. Amikacin (1/48 hrs I.V.) and oral ciprofloxacin (250 mg, twice daily) were followed for six months with a good and sustained clinical response (Figure 1). Six months after completion of the course of antibiotics, a Tenckhoff catheter was reinserted and the patient successfully returned to PD. Seven months later, he received a cadaveric kidney transplant and he is doing very well.

Figure 2.

Radiologic findings. (a) Abdominal X-ray showing the PD catheter tip position in the right iliac fossa (white arrow). (b) Computerised tomography of the abdomen, showing the catheter tip resting in close contact with the pelvic wall and the colon (white arrow). (c) Computerised tomography of the abdomen, showing inflamed fat and bowel wall thickening (small white arrow).

3. Discussion

Mycobacterium fortuitum is the most commonly reported NTM associated with infection in PD patients. It belongs to group 4 (Runyon's classification) of rapidly growing NTM. These ubiquitous bacteria can be isolated from a number of natural sources including soil, dust, and water [2]. Relapsing and culture-negative peritonitis is typical. Guidelines of the International Society for Peritoneal Dialysis (ISPD) recommend that a negative dialysate culture at 3 days together with ongoing clinical evidence of peritonitis calls for specialized cultures for atypical causes of peritonitis. In case of a clinical suspicion of infection with Mycobacterium spp., repeated smears and centrifuge of effluent sediment with a combination of solid- and fluid-medium culture are suggested [3]. NTM PD peritonitis episodes respond neither to antibiotics typically prescribed for bacterial peritonitis nor to antituberculous medications. It is important that clinicians maintain a high level of suspicion for NTM peritonitis when PD associated peritonitis cases are culture negative or refractory to standard antibiotic treatment. The failure to consider mycobacterial infection in the differential diagnosis of peritonitis may lead to delayed diagnosis and treatment.

We conducted a systematic review of the literature focusing on M. fortuitum PD-related peritonitis. Twenty reports were identified. Five patients were women and 15 were men with an age ranging between 15 and 83 years. Duration of PD prior to M. fortuitum peritonitis ranged from a few days to 8 years. Fever and abdominal pain were the predominant clinical features at presentation. A delayed microbiological diagnosis was seen in almost all reports. M. fortuitum infection showed a propensity for abscess formation and tunnel infection (as reported in 7 of the 20 cases described). The Tenckhoff catheter was removed in all but 2 of the reported cases. The duration of the antibiotic therapy varied widely from 1 week to 12 months. The more common antibiotics used included amikacin (n = 10), clarithromycin (n = 6), ciprofloxacin (n = 5), and doxycycline (n = 4). Combined agents were commonly prescribed. Three deaths were reported in patients with M. fortuitum PD peritonitis. The main characteristics of the clinical cases reported in the literature are summarized in Table 1 [2, 4–16].

Table 1.

M. fortuitum PD-related peritonitis: patient characteristics, antibiotic therapies, and outcome.

| Case [ref.] |

Age (years)/sex |

Cause of ESKD |

Time on PD (months) |

Antibiotic therapy | Treatment duration |

PD catheter removal |

Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 [4] |

32/M | NA | NA | Amikacin, tetracycline ciprofloxacin |

Months | Yes | Resistant infection |

|

| |||||||

| 2 [5] |

42/M | DN | NA | Amikacin, doxycycline | 20 days | Yes | Recovery |

|

| |||||||

| 3 [5] |

40/M | DN | 24 | Amikacin doxycycline |

21 days | Yes | Death |

|

| |||||||

| 4 [6] |

16/M | SLE | 36 | Ciprofloxacin Trimethoprim Sulfamethoxazole |

Months | Yes | Recovery |

|

| |||||||

| 5 [7] |

35/M | GN | 10 | Amikacin | NA | Yes | Recovery |

|

| |||||||

| 6 [8] |

71/M | GN | 10 | Amikacin Clarithromycin Trimethoprim Sulfamethoxazole |

3 months | Yes | Recovery |

|

| |||||||

| 7 [2] |

83/F | NS | 11 | Ciprofloxacin Clofazimine |

3 months | No | Recovery |

|

| |||||||

| 8 [2] |

61/M | GN | 0.33 | Amikacin | 1 week | Yes | Recovery |

|

| |||||||

| 9 [2] |

50/M | GN | 96 | Imipenem Amikacin Sulfamethoxazole |

NA | Yes | Improved |

|

| |||||||

| 10 [9] |

33/M | HK | NA | Clarithromycin Bactrim |

6 months | Yes | Improved |

|

| |||||||

| 11 [9] |

71/F | AED | <1 | Amikacin Bactrim Clarithromycin |

3 months | Yes | Death |

|

| |||||||

| 12 [10] |

45/F | NA | 36 | Isoniazid Rifampin Ethambutol |

6 months | Yes | Recovery |

|

| |||||||

| 13 [11] |

65/M | NA | 60 | Levofloxacin Clarithromycin |

12 months | No | Recovery |

|

| |||||||

| 14 [12] |

59/M | NS | 1 | Vancomycin Doxycycline |

1 month | Yes | Recovery |

|

| |||||||

| 15 [12] |

65/M | DN | NA | Minocycline | 6 days | Yes | Recovery |

|

| |||||||

| 16 [13] |

38/F | HUS | 6 | Moxifloxacin, clarithromycin, and doxycycline | NA | Yes | Recovery |

|

| |||||||

| 17 [14] |

62/M | DN | 9 | Cefoxitin, clarithromycin | Weeks | Yes | Recovery |

|

| |||||||

| 18 [15] |

47/M | DN | 6 | Clarithromycin, meropenem, ciprofloxacin |

2 months | Yes | Recovery |

|

| |||||||

| 19 [8] |

68/F | DN | 48 | Amikacin, ciprofloxacin | 6 months | Yes | Death |

|

| |||||||

| 20 [16] |

15/M | NA | NA | Amikacin, cefoxitin |

NA | Yes | NA |

AED: atheroembolic disease; DN: diabetic nephropathy; ESKD: end-stage kidney disease; GN: glomerulonephritis; HK: horseshoe kidney; HUS: hemolytic uremic syndrome; NA: not available; NS: hypertensive nephrosclerosis; PD: peritoneal dialysis; SLE: lupus nephritis.

The safety and timing for attempted reinsertion of Tenckhoff catheters after treatment, and technique survival, are incompletely reported. The ISPD guidelines recommend consideration of catheter removal following a diagnosis of mycobacterial peritonitis although data supporting this recommendation are limited [3].

In our case, we noticed that the peritoneal dialysis catheter was removed because of the refractory PD peritonitis well before the identification of M. fortuitum. The contact of the intra-abdominal extremity of PD catheterwith the colon could be involved in an enteric bacterial leak to the peritoneum. The presence of M. fortuitum in the PD effluent culture is most likely secondary to PD catheter colonization. The environmental peritoneal catheter infection by M. fortuitum via the exit site has been reported [17]. In our case, this hypothesis was not confirmed as identification of M. fortuitum on the exit site culture was not done.

NTM are a rare but serious cause of PD peritonitis with high rates of Tenckhoff removal and conversion to hemodialysis. The literature review has shown that M. fortuitum was usually sensitive to amikacin, quinolones, and imipenem [18]. We advocate that optimal treatment of this infection is PD catheter removal and antibiotic therapy for at least 6 months after eradication of the bacteria.

Abbreviations

- AED:

Atheroembolic disease

- DN:

Diabetic nephropathy

- ESKD:

End-stage kidney disease

- GN:

Glomerulonephritis

- HK:

Horseshoe kidney

- HUS:

Hemolytic uremic syndrome

- NA:

Not available

- NS:

Hypertensive nephrosclerosis

- PD:

Peritoneal dialysis

- SLE:

Lupus nephritis.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper.

References

- 1.Vas SI. Infections of continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis catheters. Infectious Disease Clinics of North America. 1989;3(2):301–328. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.White R, Abreo K, Flanagan R, et al. Nontuberculous mycobacterial infections in continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis patients. American Journal of Kidney Diseases. 1993;22(4):581–587. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(12)80932-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li PK, Szeto CC, Piraino B, et al. Peritoneal dialysis-related infections recommendations: 2010 update. Peritoneal Dialysis International. 2010;30(4):393–423. doi: 10.3747/pdi.2010.00049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Woods GL, Hall G, Schreiber M. Mycobacterium fortuitum peritonitis associated with continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 1986;23(4):786–788. doi: 10.1128/jcm.23.4.786-788.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Soriano F, Rodriguez-Tudela JL, Gómez-Garcés JL, Velo M. Two possibly related cases of Mycobacterium fortuitum peritonitis associated with continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis. European Journal of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases. 1989;8(10):895–897. doi: 10.1007/BF01963778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dunmire RB, III, Breyer JA. Nontuberculous mycobacterial peritonitis during continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis: case report and review of diagnostic and therapeutic strategies. American Journal of Kidney Diseases. 1991;18(1):126–130. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(12)80303-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kolmos HJ, Brahm M, Bruun B. Peritonitis with Mycobacterium fortuitum in a patient on continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis. Scandinavian Journal of Infectious Diseases. 1992;24(6):801–803. doi: 10.3109/00365549209062468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Renaud CJ, Subramanian S, Tambyah PA, Lee EJC. The clinical course of rapidly growing nontuberculous mycobacterial peritoneal dialysis infections in Asians: a case series and literature review. Nephrology. 2011;16(2):174–179. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1797.2010.01370.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vera G, Lew SQ. Mycobacterium fortuitum peritonitis in two patients receiving continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis. American Journal of Nephrology. 1999;19(5):586–589. doi: 10.1159/000013524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Youmbissi JT, Malik QT, Ajit SK, Al Khursany IA, Rafi A, Karkar A. Non tuberculous mycobacterium peritonitis in continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis. Journal of Nephrology. 2001;14(2):132–135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tang S, Tang AW, Lam WO, Cheng YY, Ho YW. Successful treatment of Mycobacterium fortuitum peritonitis without tenckhoff catheter removal in CAPD. Peritoneal Dialysis International. 2003;23(3):304–305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jiang SH, Roberts DM, Dawson AH, Jardine M. Mycobacterium fortuitum as a cause of peritoneal dialysis-associated peritonitis: case report and review of the literature. BMC Nephrology. 2012;13(1, article 35) doi: 10.1186/1471-2369-13-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Simbli M, Niaz F, Al-Wakeel J. Encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis in a peritoneal dialysis patient presenting with complicated Mycobacterium fortuitum peritonitis. Saudi Journal of Kidney Diseases and Transplantation. 2012;23(3):635–641. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ranganathan D, Fassett R, John G. Mycobacterium fortuitum peritonitis in a patient receiving continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis. Saudi Journal of Kidney Diseases and Transplantation. 2013;24(5):1003–1004. doi: 10.4103/1319-2442.118073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zewinger S, Meier C-M, Fliser D, Klingele M. Mycobacterium fortuitum peritonitis in peritoneal dialysis and its effects on the peritoneum. Clinical Nephrology. 2013 doi: 10.5414/CN107704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.LaRocco MT, Mortensen JE, Robinson A. Mycobacterium fortuitum peritonitis in a patient undergoing chronic peritoneal dialysis. Diagnostic Microbiology and Infectious Disease. 1986;4(2):161–164. doi: 10.1016/0732-8893(86)90151-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jo A, Ishibashi Y, Hirohama D, Takara Y, Kume H, Fujita T. Early surgical intervention may prevent peritonitis in cases with Tenckhoff catheter infection by Nontuberculous Mycobacterium . Peritoneal Dialysis International. 2012;32(2):227–229. doi: 10.3747/pdi.2011.00080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brown BA, Wallace RJ, Jr., Onyi GO, de Rosas V, Wallace RJ., III Activities of four macrolides, including clarithromycin, against Mycobacterium fortuitum, Mycobacterium chelonae, and M. chelonae-like organisms. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 1992;36(1):180–184. doi: 10.1128/aac.36.1.180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]