Abstract

Urban adolescents face many barriers to health care that contribute to health disparities in rates of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and unintended pregnancy. Designing interventions to increase access to health care is a complex process that requires understanding the perspectives of adolescents. We conducted six focus groups to explore the attitudes and beliefs about general and sexual health care access as well as barriers to care among urban, economically disadvantaged adolescents. Participants first completed a written survey assessing health behaviors, health care utilization, and demographics. The discussion guide was based on the Theory of Planned Behavior and its constructs: attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control. Transcripts of group discussions were analyzed using directed content analysis with triangulation and consensus to resolve differences. Fifty youth participated (mean age 15.5 years; 64% female; 90% African American). Many (23%) reported missed health care in the previous year. About half (53%) reported previous sexual intercourse; of these, 35% reported no previous sexual health care. Youth valued adults as important referents for accessing care as well as multiple factors that increased comfort such as good communication skills, and an established relationship. However, many reported mistrust of physicians and identified barriers to accessing care including fear and lack of time. Most felt that accessing sexual health care was more difficult than general care. These findings could inform future interventions to improve access to care and care-seeking behaviors among disadvantaged youth.

Keywords: Adolescent, Health Care Disparities, Health Care Quality, Access, Evaluation

Adolescents in the U.S. face many barriers to health care including lack of access to knowledgeable providers and concerns about privacy and cost (Cassidy & Whittaker, 2003; Hock Long, Herceg Baron, Cassidy, & Whittaker, 2003; M. Miller et al., 2011). These barriers contribute to health challenges as evidenced by high rates of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and unintended pregnancy (Centers for disease control and prevention [CDC], 2011; Martin et al., 2013).

STIs and unintended pregnancy are general public health issues, but African American and economically disadvantaged youth are disproportionately affected (Forhan, et al., 2009; Kost & Hallfors, Iritani, W. Miller, & Bauer, 2007; Henshaw, 2012; W. Miller, et al., 2004). Numerous patient, provider, and health system factors contribute to disparities including access barriers to high quality care (Hogben & Leichliter, 2008; Newacheck, Hung, Park, Brindis, & Irwin, 2003; Parrish & Kent, 2008). Access barriers can result in reliance on safety net hospitals and emergency departments (EDs), which in turn may negatively affect opportunities for preventive and reproductive care (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2011; Fiscella & Williams, 2004).

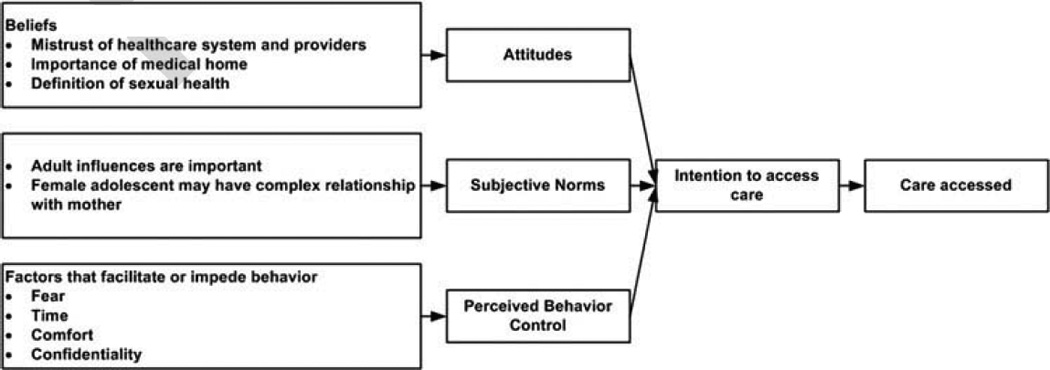

Designing interventions to increase adolescent access to care is a complex process. Understanding the perspectives of adolescents is vital to success. A conceptual framework that can be used to model adolescent behavior is the theory of planned behavior (TPB). This theory states that attitudes, social norms and perceived behavioral control influence behavioral intention, which in turn influences actual behavior (Ajzen, 1985). The TPB has been assessed and validated for understanding a variety of adolescent health issues such as exercise, healthy eating, and sexual health behaviors (Hutchinson & Wood, 2007; Mollen et al., 2008; Rah, Hasler, Painter, & Chapman-Novakofski, 2004; Tsorbatzoudis, 2005). The aim of this study was to use the TPB framework to explore attitudes and beliefs about general and sexual health care access as well as barriers to care among urban, disadvantaged adolescents.

METHODS

The study team conducted focus groups with adolescents recruited from urban community based organizations (CBOs). The study protocol and consent procedures (including written consent waiver) were approved by the hospital institutional review board. The lead author introduced the study and provided participants with written and verbal information about the study and procedures including voluntary nature of participation, audio-recording of sessions, and potential risks to confidentiality. The author answered any questions. Following national guidelines, we did not obtain parental consent for this minimal risk study and obtained verbal consent from participants (Field & Berman, Eds., 2004; Santelli et al., 2003). This same information was provided again by the moderator (SJ) prior to initiating the audio-recording.

Population and Study Setting

Participants were recruited by purposeful sampling from CBOs within a large, Midwestern city. Targeted CBOs provided a wide variety of services and programming to primarily African American adolescents from urban, economically disadvantaged areas. All but one CBO were local organizations. Adolescents aged 14 to 18 years receiving services at participating CBOs were eligible. A CBO liaison assisted with the identification of volunteer participants. Participants gave verbal consent and received a $25 gift card.

Focus Groups

A detailed moderator’s guide, based on the TPB, was developed by a multidisciplinary team with expertise in adolescent health and psychology, health services research, and qualitative methods. The guide was designed to explore participant’s perceptions of TPB constructs: attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control. Questions from the moderator’s guide are listed in Table 1, and probes were used to garner detail and examples.

Table 1.

Moderator’s Guide: Primary Questions

| General Health |

| What is your experience with accessing or getting health care? Is it hard to get? Where do you go if you are sick or need to talk to a doctor? |

| How do you decide where you go? (Probes: location, type of illness vs. check ups, hours, parent influence) |

| What helps you trust a doctor/clinic? |

| Do you have a medical home with a personal or regular doctor that you can see? |

| How important is having a medical home or personal health clinic with a personal or regular doctor that you can go to? |

| Sexual Health |

| When I say “sexual health” what comes to mind? |

| What does it mean to you to be sexually healthy or to have good sexual health? |

| Where do you go for information about sexual health? |

| If you have a sexual health issue, where do you go/where would you go for care? |

| What factors would be important in helping you decide where to go and what doctor to see? |

| What helps you feel more comfortable about getting sexual health care? |

| What are some of the challenges you face in getting sexual health care? |

| What makes getting care for sexual health easier or harder than getting general health care? |

| What rights to privacy or confidentiality do you think or know you have about your health? |

A female, Caucasian, PhD psychologist trained in focus group moderation (SJ) conducted the semi-structured sessions, which were homogeneous for gender. Before each session, participants completed a short, written survey assessing health behaviors, health care utilization, and demographics. The moderator introduced the project and explained the purpose of the session was “to hear your thoughts, opinions and beliefs about health care and in particular, access to sexual health care”. The moderator defined the term medical home as a “place where the nurses and doctors know you well and know about your health history. Care should focus on you, should be easy to get, and should be explained in a way that is easy to understand.” (Medical Home Initiatives for Children With Special Needs Project Advisory Committee, 2002). Each session lasted 60 to 90 minutes. A second member of the research team was present to take written notes. All sessions were audio-taped and transcribed verbatim but without names or personal identifiers.

Analysis

Iterative qualitative analysis was conducted using directed content analysis (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005). Transcribed data were entered into NVivo 9 (QSR International, Cambridge, MA) for easier data management. Each analysis team member (MM, SJ, JW) read all transcripts, assigned first-level codes, and summarized key findings into an analytic memo. At an initial meeting, memos were shared and first-level codes were grouped into categories through a consensus process. Each category was named with an identifiable descriptive term and definitions were formulated. Team members then independently recoded transcripts using descriptive categories. New categories were identified and recorded in memos. These memos were shared at a second meeting and original and new categories were clustered into themes. Each team member then reread the transcripts to assure thematic fit for all focus group content. An additional author (JL) reviewed the transcripts and final summative memo to uncover possible areas of interpretive disagreement. Triangulation and consensus were used throughout analysis to resolve differences and maximize reliability. The entire coding and category decision-making process was documented to maximize reliability and validity.

RESULTS

Six groups (three for each gender) were conducted with 50 participants from July through November, 2012. No eligible person refused participation. The focus groups ranged in size from 3 to 12 participants. The mean age was 15.5 ± 1.3 years, 64% were female, and almost all self-identified as non-White (characteristics are described in Table 2). About half (53%) reported previous sexual intercourse (PSI); two females reported bisexual activity. Nearly one-third (30%) did not use a condom at last intercourse (of those who reported previous sexual activity). Among those reporting PSI, 35% reported they had never had a health visit for birth control or pregnancy/STI testing and 12% reported it had been > 1 year since receiving this type of care. Many subjects (30%, 8 of whom reported PSI) had not talked with a parent or guardian about STIs and how to prevent them and slightly fewer (22%, 8 of whom reported PSI) reported they had not talked about pregnancy prevention.

Table 2.

Participant characteristics (N=50)

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD),y | 15.5 ± 1.3 |

| Female | 32 (64) |

| Hispanic Ethnicity* | 3 (6) |

| Race | |

| White | 1(2) |

| African American | 45 (90) |

| Mixed Race/other | 4 (8) |

| Previous sexual intercourse* | 26 (53) |

| ED Visit in past year* | 24 (49) |

| Missed health care in past year ** | 11 (23) |

| Reported personal doctor or clinic | 29 (58) |

| Recent health check-up (>1 year) | 39 (78) |

N=49

N=48

Focus Group Themes

Broad themes emerged within each TPB construct (Figure 1). Each theme is described below and in corresponding tables. A clear saturation of themes occurred following the 6 focus groups, wherein no new responses arose.

Figure 1.

Modified TPB, highlighting themes related to accessing general and sexual health care by adolescents.

Attitudes

Three themes related to attitudes toward health care and care-seeking behavior were identified (Table 3 provides illustrative quotes).

Table 3.

Themes and participant quotes within the attitude construct

| Adolescents are divided on physician trust | “I think doctors be lying to you.” | Female |

| “Don't tell me it's going to hurt a pinch because I will be mad when it hurt, like, really bad.” | Female | |

| “I trust my doctor because that's been my doctor ever since I was born.” | Male | |

| “I don't trust them so I kind of get scared…because my life is in their hands.” | Male | |

| “They just try to find something wrong with you.” | Male | |

| “I mean, it goes back to, like, being able to tell them what you want to be able to tell, like, your parents and stuff. And like, you can go in there and tell them.” | Female | |

| Having a medical home is important | “You never know when you're going to need them.” | Male |

| “Like you can trust them more if it's someone who has kind of history with you.” | Female | |

| “It's important because you trust them more than other people because you've been there before.” | Male | |

| “Because they already know your history, your background, so it ain't too much – they could probably figure out on the spot what's wrong with you without touching all your body parts and all that.” | Female | |

| Sexual health is narrowly defined by most adolescents | “You ain't got no diseases.” | Male |

| “Talking to the person you are sexually active with, seeing what they've been doing.” | Female | |

| “Always use condoms. And – or just stay away from sex, you know what I'm saying?” | Male | |

| “Like if you are sexually active, like, go get checkups.” | Female |

Adolescents are divided on physician trust

Overall, participants were divided on whether they trusted doctors and other health care providers. Those who trusted their doctor often cited a long history and relationship with their doctor and/or clinic. Participants identified other factors facilitating trust such as maintaining patient confidentiality, providing non-judgmental care, and demonstrating clinical competence.

Factors contributing to mistrust included: lack of established relationship, fear of the unknown, poor communication, and perception of lying. Some participants expressed frustration that “sometimes your parents find out” despite promises of confidentiality.

A few subjects expressed a general distrust of physicians. One male stated, “I just don't trust nobody I don't know.” One male suggested race was a factor that contributed to mistrust. However, when other youth challenged this view, he quickly said, “I don’t discriminate…I take that back.”

Many participants shared stories about personal and/or familial experiences with providers that seemed to contribute to mistrust. One female who said, “they cut my mama open and closed her up and it's not helping her.” Several female adolescents questioned the care provided by doctors who would look at “private parts” or evaluate them with “stuff I don’t need.”

Having a Medical Home is Important

Most participants stated they had a medical home. Most thought a medical home was important because the provider knew their personal history and would be able to provide more efficient and accurate care. Many reported a sense of security from having a medical home such as one female who reported her provider knows “to check up on me.”

Sexual Health is Narrowly Defined

The majority participants associated sexual health with the absence of disease. Many felt being “sexually healthy” would entail getting tested for sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) and Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV), avoiding unintended pregnancy, and using condoms. A few mentioned getting a “vaccine,” abstaining from sexual activity, or communicating with sex partners. One person said that “not doing it until you're ready” was important for sexual health.

Subjective Norms

Two themes related to subjective norms were identified: adults are important influences and many adolescent females have complex relationships with their mothers (Table 4 provides illustrative quotes). Overall, mothers and parents were often mentioned as the most important referents for health care. Most adolescents reported that an important adult influenced their decisions about where to access care. This adult was most often their mother or father, but godmother, grandparent, and older sibling and cousin were also mentioned. Some adolescents mentioned friends as well. Males more often deferred to their mothers’ judgment, with many saying they go “wherever my mama take(s) me.” Other determinants influencing where to access care included: location, cost, problem severity or urgency, wait time, doctor or friend referral, insurance status, and provider reputation. For sexual health care, both males and females mentioned visiting somewhere outside of where they regularly get care, typically in hopes of ensuring privacy. Adolescents identified a wide range of referents for accessing sexual health information. For males this included: parents, dad, friends, teachers, older people/those with experience, brothers, coaches, and regular doctor. For females, this included parents (more often mother), friends, regular doctor, and other family.

Table 4.

Participant Quotes Within the Subjective Norms Construct

| Theme | Illustrative Quote | Gender |

|---|---|---|

| Adults are Important influences | “My mama always decides where to go.” | Female |

| “I'm sure they (parents) know what they're doing.” | Male | |

| Many adolescent females have complex relationships with their mothers | “I understand everybody have their friends. You know, moms' have their best friends…[but] your best friend don't need to know my business.” | Female |

| “Why tell me I can come talk to you but you throw it back in my face?” | Female | |

| “I feel comfortable talking to my mama. I don't really talk to the doctor about stuff like that.” | Female | |

| “Your mama's gonna tell you exactly how it is. Doctors, they be trying to sugar coat it.” | Female | |

| “And for your mother to sit up there and assume that you're doing things, that hurts, because she can't – that shows that she can't trust you.” | Female | |

| “I think it's because of the fear, like, you know some kids be scared to tell their mama.” | Female | |

| “My mama know me real good.” | Female | |

| “Like, I tell my mama, ‘Oh, I need to get a pregnancy test,' or something, but, like, I wouldn't tell her everything that happened for me to get a pregnancy test.” | Female |

In comparison to males, females described a more complex relationship with mothers. Regarding accessing care and information, as well as issues of confidentiality, males more often indicated that mothers were the most important referent—someone who would make decisions, provide information, and be aware of the adolescents’ personal health matters. Female subjects often referred to their mother as an important influence and provided details about advantages and limitations to this relationship. Females were divided on how comfortable they were discussing sensitive topics with their mother. Several felt like their mother knew them “like the back of their hand” and a few appreciated the straightforward approach of their mother. In contrast, others felt that their mother wouldn’t understand or might “judge” them if they expressed a sexual health concern.

Perceived Behavioral Control

Participants identified four main factors that could facilitate or impede accessing care: comfort, fear, confidentiality, time (Table 5 provides quotes). Overall, most felt that accessing sexual health care was more difficult than general care because of factors related to comfort (such as embarrassment and unfamiliarity).

Table 5.

Themes and Participant Quotes within the Perceived Behavioral Control Construct

| Theme | Illustrative Quote | Gender |

|---|---|---|

| Comfort | “But after I got a certain age, I didn't want a man looking at me and feeling on me.” | Female |

| “The men [are] kinda rough with you.” | Male | |

| “It's just like a family. Like I said, they care about what's happening to you.” | Female | |

| “You don't want a man touching you. You feel uncomfortable.” | Male | |

| “I've been having my doctor since I was a newborn, so he knows everything for me.” | Female | |

| Fear | “I don't know what they're putting in you.” | Male |

| “And then they test on you [and] you pass out or something.” | Female | |

| “At the hospital, they want to like test you out for all this different stuff. And like, it's nothing that you said was wrong with you, it seems like.” | Female | |

| “But it's like if you don't got insurance or anything, it's like they do use you as a test, uh– a lab rat…And then when we're done with you, we're going to go to the next person that don't got it.” | Female | |

| “I would want my grandma to be in there because I don't want just nobody just feeling up on me.” | Female | |

| “It seems like some parents just want to explode the first time you mention something about sex to them.” | Female | |

| Confidentiality | “I want to talk to, like, people I know ain't gonna talk to my mama.” | Male |

| “Sometimes, I could tell my mama stuff, like, but not personal stuff. I always tell my doctor.” | Female | |

| “I don't think I need to hide anything from my mama.” | Male | |

| “Even if you don't want them to tell your parents about it, they're going to have to do it anyway…that's their job to tell the parents about it.” | Male | |

| “I think they should have like a doctor or a hospital or something where only teens could go and they mama ain't got to know nothing about it.” | Female | |

| “Well, parents are like flies.” | Female | |

| Time | “I want to be able to get in, be seen, and get my problem taken care of so we can be done with it.” | Male |

| “It's OK, it's like if they make you wait and they do their job right, but sometimes they make you wait and they don't do nothing.” | Female |

Comfort

Factors that facilitated comfort included: providing respectful care, explaining care and procedures, good communication skills (use of age-appropriate language, listening), established relationship, and nice facilities. Several felt respectful care was important, “even if you got a disease” and a few specifically appreciated doctors who “don’t judge you.” Many subjects felt good communication was important. This included “communicating back with you” and being honest with subjects “even if it's bad.” Several felt it was important to obtain permission to examine the patient or perform a test. Adolescents described many characteristics representative of a medical home as providing comfort. Many felt that having an established relationship with a provider facilitated comfort and efficiency. One teen said, “you feel like someone's watching out for you.” Overall, subjects mentioned décor, small tokens, friendly staff, and welcoming environment as factors that contributed to patient comfort.

Barriers to comfort were: poor communication skills, male providers (for both genders), and lack of history with providers. Many adolescents expressed frustration with doctors’ communication skills, stating that doctors “use big words” and are hard to understand. Several subjects expressed confusion about why a doctor would do certain tests or examine specific parts of the body, especially if they did not understand the connection to their specific health complaint. This led several to think that doctors might be lying or incompetent. One subject simply wondered, “What is going on here?” Many males and females expressed a preference for female health care providers, especially for sexual health concerns. Several males felt that women practitioners were gentler. Female subjects often commented that it was embarrassing to talk with a male provider and indicated that the physical exam felt inappropriate. Lack of continuity was especially influential on one female who commented, “…that’s why I don’t tell nothing.”

Fear

Fear was a major factor influencing decisions for accessing care, mistrust in the health care system and providers, and desire for parental involvement in care. Many subjects expressed a fear of being “experimented on” which might include unneeded tests, physical exams, or treatments. Several were afraid because they believed a doctor or provider can “put anything in you.” One felt people without insurance were at higher risk of becoming a “lab rat.” When explaining why he wants a parent present in the room during a health visit, one male said, “…if something happens, they got my back.” In contrast, among females, fear of negative parental (and specifically maternal) reaction to sexual health needs influenced desire for confidentiality. One said she could tell the doctor things she wouldn’t tell her mother because the doctor “can’t hit you.”

Confidentiality

Participants expressed limited knowledge about their own right to confidentiality in general and sexual health care. Many reported hearing about the concept, but were unable to describe how it applied to their care. Some thought that providers would tell parents about all health conditions. Many felt that a provider would disclose information under certain conditions such as if the patient has “a disease”, is pregnant, or is “about to die.” Some felt providers would not disclose information if a patient specifically asked them not to. A few shared that they had talked about confidentiality with a health care provider. Some participants expressed frustration that “sometimes your parents find out” despite promises of confidentiality from providers.

Participants were divided on their desire for confidentiality. While several felt confidential care increased overall comfort (especially around sensitive topics), a few felt that having their parents present during an exam increased their comfort. Some preferred for the provider to facilitate a private health interview by directly asking the parent to step out, while fewer mentioned they preferred to be asked if they want a parent present. Males were more likely to report they wanted their parents to participate in their care.

Overall, females were more hesitant to share health information with family members, particularly with mothers. Many expressed concern that mothers would not keep information private and would disclose information with friends and family. Some worried that their relationship with their mother might be damaged or changed if they shared information about their sexual health needs. A few shared that family experiences with teen pregnancy impacts their desire to keep sexual health information private, so their mother won’t make judgments or lose trust.

Time

Many mentioned the importance of prompt care, and having a doctor who would “handle it right then and there.” Many adolescents felt that waiting for care can be a barrier. Overall, subjects were frustrated by time delays in the waiting or treatment room but rarely mentioned frustration in obtaining a timely appointment. In the emergency care setting, a few acknowledged that other patients, who may be sicker, might be seen sooner. However, a few participants disagreed with this type of triage and felt that patients should be seen “as fast as they come there.”

Discussion

This study describes the perspectives of urban, economically-disadvantaged youth who shared detailed attitudes, norms, and barriers related to accessing general and sexual health care. Specifically, these youth valued adult influences when accessing care as well as multiple factors that increased comfort including good communication skills and an established relationship with a provider. However, many reported mistrust of doctors and barriers to accessing care.

Most teens reported having a regular source of medical care and felt having a medical home was important, when discussed as part of the focus group. However, this was inconsistent with written survey responses, where only 58% of participants reported having a personal doctor or clinic. Nearly one-quarter of participants had not completed a recent preventive health visit, which is somewhat better than national studies showing up to 41% of poor adolescents lack annual health visits (Newacheck, Hung, Park, Brindis, & Irwin, 2003).

Many subjects expressed a mistrust of doctors and familial experiences seemed to be influential. Mistrust of the medical system is generally higher among African Americans adults compared with other racial/ethnic groups (Doescher, Saver, Franks, & Fiscella, 2000; LaVeist, Isaac, & Williams, 2009; Moseley, Clark, Gebremariam, Sternthal, & Kemper, 2006). The adult literature also demonstrates that medical mistrust is a robust predictor of underutilization of health services (LaVeist, Isaac, & Williams, 2009). Among adults, the continuity of physician relationship and provider communication style have been linked with patient trust (Moseley, Clark, Gebremariam, Sternthal, & Kemper, 2006). Our participants also reported these factors affected trust. While some studies have evaluated parental trust in a child’s provider, studies assessing adolescent perceptions on physician trust are lacking and represent an area worthy of further exploration (Horn, Mitchell, Wang, Joseph, & Wissow, 2012; Moseley, Freed, Bullard, & Goold, 2007).

The social determinants of health framework examines the circumstances in which people are born, grow up, and live, as well as the health care systems put in place to address illness (Raphael, 2011). Consistent with this literature, study participants described complex barriers—at both the individual and system levels—to accessing care. Many of these identified barriers can be considered social determinants of health including lack of regular care, concerns about cost and privacy, and lack of culturally competent and knowledgeable providers (Parrish & Kent, 2008). The importance of social determinants of health is demonstrated in studies that show disparities in adolescent utilization of primary care, even after controlling for insurance coverage (Elster, Jarosik, VanGeest, & Fleming, 2003; Raphael, 2011). Although daunting, mounting evidence indicates that attempts to address social determinants of health will be required to improve the overall health of adolescents.

Limitations

Several study limitations might be considered, some of which are inherent in qualitative methods (Giacomini & Cook, 2000). While sample homogeneity allowed us to describe specific factors affecting behavior, these results may not be generalizable to other racial/ethnic groups or youth outside of the Midwest. It is possible that use of a Caucasian moderator may have hindered communication among participants. While the influence of potential bias among investigators cannot be fully neutralized, we utilized an experienced, multidisciplinary team to minimize this possibility. Researcher triangulation with five study members enhanced credibility of analysis.

Conclusion

During focus group sessions, urban, economically-disadvantaged adolescents valued adult influences and multiple factors that increased comfort, but many described mistrust of doctors and barriers to accessing care. These findings could inform future interventions to improve access to care and care-seeking behaviors among disadvantaged youth.

References

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Access to health care: National Healthcare Quality Report. Rockville, MD: 2011. Chapter 9. Retrieved from http://www.ahrq.gov/research/findings/nhqrdr/nhqr11/chap9.html#. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen I. From intentions to actions: A theory of planned behavior. In: Kuhl J, Beckmann J, editors. Action Control - From Cognition to Behavior. Springer Berlin Heidelberg: 1985. pp. 11–39. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for disease control and prevention. Sexually transmitted disease surveillance. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2011. p. 2012. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/std/stats11/adol.htm. [Google Scholar]

- Doescher MP, Saver BG, Franks P, Fiscella K. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Perceptions of Physician Style and Trust. Archives of Family Medicine. 2000;1156:1159–1160. doi: 10.1001/archfami.9.10.1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elster A, Jarosik J, VanGeest J, Fleming M. Racial and ethnic disparities in health care for adolescents: a systematic review of the literature. Archives of pediatrics & adolescent medicine. 2003;157(9):867. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.157.9.867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field MJ, Berman RE. The ethical conduct of clinical research involving children. National Academies Press; 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiscella K, Williams DR. Health disparities based on socioeconomic inequities: implications for urban health care. Academic Medicine. 2004;79(12):1139–1147. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200412000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forhan S, Gottlieb S, Sternberg M, Xu F, Datta S, McQuillan G, Markowitz L. Prevalence of sexually transmitted infections among female adolescents aged 14 to 19 in the United States. Pediatrics. 2009;124(6):1505–1512. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giacomini MK, Cook DJ. Users’ guides to the medical literature: XXIII. Qualitative research in health care A. Are the results of the study valid? JAMA: the journal of the American Medical Association. 2000;284(3):357–362. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.3.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giacomini MK, Cook DJ. Users’ guides to the medical literature: XXIII. Qualitative research in health care B What are the results and how do they help me care for my patients? JAMA: the journal of the American Medical Association. 2000;284(4):478–482. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.4.478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallfors DD, Iritani BJ, Miller WC, Bauer DJ. Sexual and drug behavior patterns and HIV and STD racial disparities: the need for new directions. American Journal of Public Health. 2007;97(1):125–132. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.075747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hock Long L, Herceg Baron R, Cassidy AM, Whittaker PG. Access to adolescent reproductive health services: financial and structural barriers to care. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2003;35(3):144–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogben M, Leichliter JS. Social determinants and sexually transmitted disease disparities. Sexually transmitted diseases. 2008;35(12):S13–S18. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31818d3cad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horn IB, Mitchell SJ, Wang J, Joseph JG, Wissow LS. African-American Parents’ Trust in their Child’s Primary Care Provider. Academic Pediatrics. 2012;5:399–404. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2012.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative health research. 2005;15(9):1277–1288. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katherine Hutchinson M, Wood EB. Reconceptualizing Adolescent Sexual Risk in a Parent Based Expansion of the Theory of Planned Behavior. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2007;39(2):141–146. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2007.00159.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kost K, Henshaw S. Race and Ethnicity. New York: Guttmacher Institute; 2012. [accessed February, 8, 2012]. US Teenage Pregnancies, Births and Abortion, s, 2008: National Trends by Age. [Online]. http://www. guttmacher. org/pubs/USTPtrends08. pdf. [Google Scholar]

- LaVeist TA, Isaac LA, Williams KP. Mistrust of health care organizations is associated with underutilization of health services. Health services research. 2009;44(6):2093–2105. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2009.01017.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Ventura SJ, Osterman MJ, Mathews TJ. Births: final data for 2011. National Vital Statistics Report. 2013;62(1) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medical Home Initiatives for Children With Special Needs Project Advisory Committee. American Academy of Pediatrics. The medical home. Pediatrics. 2002;110(1 Pt 1):184–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MK, Plantz DM, Dowd MD, Mollen CJ, Reed J, Vaughn L, Gold MA. Pediatric emergency health care providers’ knowledge, attitudes, and experiences regarding emergency contraception. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2011;18(6):605–612. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2011.01079.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller W, Ford C, Morris M, Handcock M, Schmitz J, Hobbs M, Udry J. Prevalence of chlamydial and gonococcal infections among young adults in the United States. JAMA: the journal of the American Medical Association. 2004;291(18):2229–2236. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.18.2229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mollen CJ, Barg FK, Hayes KL, Gotcsik M, Blades NM, Schwarz DF. Assessing attitudes about emergency contraception among urban, minority adolescent girls: an in-depth interview study. Pediatrics. 2008;122(2):e395–e401. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-0009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moseley KL, Clark SJ, Gebremariam A, Sternthal MJ, Kemper AR. Parents’ trust in their child’s physician: using an adapted Trust in Physician Scale. Ambulatory Pediatrics. 2006;6(1):58–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ambp.2005.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moseley KL, Freed GL, Bullard CM, Goold SD. Measuring African-American parents’ cultural mistrust while in a healthcare setting: a pilot study. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2007;99(1):15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newacheck PW, Hung YY, Park MJ, Brindis CD, Irwin CE. Disparities in adolescent health and health care: does socioeconomic status matter? Health services research. 2003;38(5):1235–1252. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.00174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parrish DD, Kent CK. Access to care issues for African American communities: implications for STD disparities. Sexually transmitted diseases. 2008;35(12):S19–S22. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31818f2ae1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rah JH, Hasler CM, Painter JE, Chapman-Novakofski KM. Applying the theory of planned behavior to women’s behavioral attitudes on and consumption of soy products. Journal of nutrition education and behavior. 2004;36(5):238–244. doi: 10.1016/s1499-4046(06)60386-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raphael JL. Differences to determinants: elevating the discourse on health disparities. Pediatrics. 2011;127(5):e1333–e1334. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-0182. Epub 2011 Apr 18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santelli JS, Rosenfeld WD, DuRant RH, Dubler N, Morreale M, English A, Rogers AS. Guidelines for adolescent health research: a position paper of the Society for Adolescent Medicine. Journal of adolescent health. 1995;17(5):270–276. doi: 10.1016/1054-139x(95)00181-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsorbatzoudis H. Evaluation of a school-based intervention programme to promote physical activity: an application of the theory of planned behavior. Perceptual and motor skills. 2005;101(3):787–802. doi: 10.2466/pms.101.3.787-802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]