Abstract

Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) is an immune disorder characterized by uncontrolled inflammation due to defective immune response. It may be familial or acquired, but both share a common feature of threatening the life of a patient and may lead to death unless treated by appropriate treatment. Here in we report a case of adult HLH.

Keywords: HLH , PUO, NK cell dysfunction

Introduction

Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) is a syndrome of uncontrolled activation of T lymphocytes and macrophages due to ineffective immune response which will lead to overproduction of inflammatory cytokines. [1, 2] This can lead to organ infiltration followed by organ failure and death if unchecked by therapy. Patients are categorized as primary or familial and secondary HLH. Primary HLH will have familial inheritance or genetic causes, usually presents in infants or younger children and unlikely to survive long term without allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Infections like cytomegalovirus (CMV) or Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) may be triggering factor but often not apparent. Secondary HLH generally refers to older children or adults who presents without family history or genetic cause, likely to have concurrent infections or medical conditions like autoimmune disorders/malignancy. Mortality from secondary HLH may be significant but the risk of recurrence is poorly defined. Here in we report adult patient with HLH who presented with prolonged fever, seizure and cytopenias.

Case Report

Twenty-two years male presented to our hospital in 2010 with complaints of seizures which were not controlled with anti-epileptic drugs for the last one year, he had four episodes of seizures which were initially focal followed by generalized tonic–clonic seizures. He had fever of six months duration before presentation to the hospital, four episodes of fever, fever is high grade, intermittent not associated with chills and rigors. He was evaluated at various hospitals and treated with multiple anti-epileptics, anti-tuberculosis drugs (ATT) and short course of steroids without any significant clinical improvement. Evaluation done at first episode of seizures in 2009, outside our hospital revealed normal physical examination, blood picture, CT scan of brain and EEG. Three months prior to admission he developed cytopenias. Evaluation done at outside hospital revealed abnormal liver function tests and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis showed lymphocytosis (25 cells and all were lymphocytes), bone marrow aspiration and biopsy showed non caseating granulomas. He was started on prednisolone and ATT with suspicion of Tuberculosis. Though there is an improvement in fever and cytopenias transiently, the problems recurred in-spite of steroids. He was re-evaluated in our hospital. He had pallor and mild hepatosplenomegaly, two centimetres below the coastal margin at the time of admission and rest of the systemic examination was normal. Bone marrow slides were reviewed and found to have bone marrow hemophagocytosis (Figs. 1, 2). Further evaluation revealed high ferritin, hypofibrinogenemia, hypertriglyceridemia fulfilling the criterion required for the diagnosis of HLH according to HLH 2004 trial. His repeated blood cultures, IgG & IgM antibodies for Herpes Simplex, Varicella Zoster, and EB virus were negative. HBsAg, HIV and HCV were negative. Chest X-ray, ultrasound abdomen and 2D echo were normal. After thoroughly excluding the bacterial, viral and fungal infections, he was started on chemotherapy protocol of HLH 2004 trial, CNS involvement was treated with Intrathecal methotrexate and hydrocortisone. Following chemotherapy (induction treatment) he went into remission and developed renal dysfunction due to cyclosporine cytotoxicity, which was recovered after the withdrawal of the drug. Due to financial constraints intravenous immunoglobulin couldn’t be given as a part of supportive therapy. He received three units of blood and didn’t require much of antibiotic support during chemotherapy. DNA sample was analysed for mutation on STXBP2, STX11, UNC13D, and PRF1 at Karolinska Institute, Sweden didn’t reveal any genetic defect which can cause primary HLH. HLA identical sister was identified for possible allogeneic stem cell transplantation (SCT) in case of unresponsiveness to induction therapy, relapse or Familial HLH. But he didn’t require further therapy either in the form of continuation treatment or allogeneic SCT as the patient continues to be in remission for 18 months following induction therapy. The following Tables 1 and 2 show serial hemogram, other parameters and liver function tests before and after therapy.

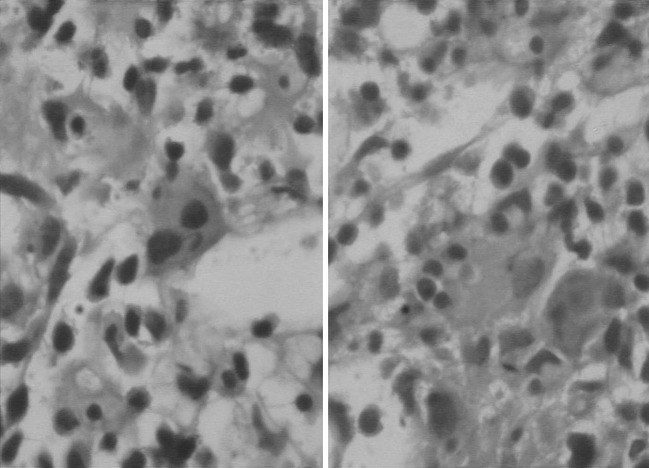

Fig. 1.

Bone marrow aspirate smears showing prominence of histiocyte with phagocytosis of hematopoietic precursors. GiemsaX400

Fig. 2.

The histiocyte in trephine biopsy showing phagocytosis. H&EX400

Table 1.

Haemoglobin, leucocytes, platelets and other parameters

| Initial presentation | Before chemotherapy | Post chemotherapy | 18 months after therapy | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Haemoglobin (g/dL) | 13.7 | 7.2 | 10.2 | 13.4 |

| Leucocyte count (μL) | 10,800 | 1,600 | 13,400 | 8,000 |

| Platelet count (μL) | 252.000 | 50,000 | 310,000 | 170,000 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 541 | 116 | 215 | |

| Fibrinogen (mg/dL) | 103 | 454 | 324 | |

| Ferritin (ng/mL) | >1,000 | 531 | 235 |

Table 2.

Liver function tests

| Before treatment | After treatment | |

|---|---|---|

| Bilirubin (total) mg/dL | 2.6 | 1.1 |

| Total proteins (g/dL) | 3.9 | 5.1 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 2.2 | 3.4 |

| SGOT (u/L) | 32 | 20 |

| SGPT (u/L) | 130 | 30 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (u/L) | 1,221 | 412 |

Discussion

In the present case, patient was relatively well preserved at the time of diagnosis even though he was symptomatic for 12 months. Following criterion were present in this patient for the diagnosis of HLH. He had temperature of >37.5 °C, splenomegaly two centimetres below the coastal margin, cytopenias (Hemoglobin-7.2 g/dL and thrombocytopenia-50,000/μL), hypertriglyceridemia (541 mg/dL), hypofibrinogenemia (105 mg/dL), ferritin (>1,000 ng/mL) and hemophagocytosis in bone marrow. Six criteria fulfilled out of 8 (five criterion required for the diagnosis of HLH) and we did not do NK cell activity or soluble CD25 due to non-availability of these tests at our institute. Table 3 shows the diagnostic criterion according to HLH 2004 trial.

Table 3.

Diagnostic criteria according to HLH 2004 trial [3]

| A. Molecular diagnosis consistent with HLH |

| Pathologic mutation of PRF 1,UNC 13D, Munc 18-2, Rab27a, STX11, SH2D1A or BIRC4 |

| OR |

| B. Five of the 8 criteria listed below are fulfilled |

| 1. Fever ≥38.5 °C |

| 2. Splenomegaly |

| 3. Cytopenias affecting at least 2 of 3 lineages in the peripheral blood (haemoglobin <9 gms/dL, for infants <4 weeks: haemoglobin 10 gms/dL, platelets <100,000/μL, neutrophils <1,000/μL) |

| 4. Hypertriglyceridemia (fasting >265 mg/dL) and/or hypofibrinogenemia <150 mg/dL |

| 5. Hemophagocytosis in bone marrow, spleen, lymph nodes or liver |

| 6. Ferritin >500 ng/mL |

| 7. Low or absent NK cell activity |

| 8. Elevated soluble CD25 |

We believe our patient has secondary HLH in view of adult onset illness, surviving without active treatment for 12 months compared to primary/familial HLH, which is fatal without treatment within 2 months [4, 5] and absence of HLH mutations. The clinical picture of HLH is due to increased inflammatory response to hyper secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines interferon gamma, tumour necrosis factor alpha etc. These cytokines which are secreted by T lymphocytes are responsible for the characteristic disease markers such as cytopenias, coagulopathy, high ferritin and infiltrates all the tissues and cause necrosis and organ failure. In spite of excessive activation of cytotoxic T cells, patients with HLH have severe impairment of the function of NK cells and cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Defective cytolytic activity whether it is genetic or acquired predisposes to HLH. Viral, bacterial or fungal infections can precipitate HLH in primary or secondary, but more common in secondary. After extensive evaluation, infection was ruled out; we discontinued the anti TB drugs. The treatment for primary HLH is induction chemotherapy followed by allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Continuation chemotherapy can be given while awaiting transplantation whereas for secondary HLH, treatment can be discontinued after the induction chemotherapy if there is response. Allogeneic stem cell transplantation to be performed only if there is recurrence after induction or if there is lack of response to induction therapy. Below flow chart represent the treatment plan of HLH.

The principal goal of induction therapy is to suppress the life threatening inflammatory process that underlies HLH. Induction chemotherapy consists of dexamethasone tapered over a period of 8 weeks, etoposide twice a week for initial 4 weeks, later once a week for 4 weeks, cyclosporine daily and Intrathecal methotrexate once a week for 4 doses starting from third week, continuation phase consists of pulses dexamethasone, etoposide once in 2 weeks and continuation of cyclosporine until transplant according to HLH 2004 trial. Most centres treats HLH according to HLH-1994 protocol in which cyclosporine is not a part of induction, we have chosen to start cyclosporine from the beginning of therapy in this case, in view of prolonged illness of patient without treatment, but he was unable to tolerate the drug and it was discontinued. Literature on HLH in India it is mostly confined to children [6–10] and there are only few adult HLH reports [11, 12]. In the present case complete work up was done including molecular analysis with successful outcome following therapy.

Conclusion

HLH should be considered as a differential diagnosis in patients with fever of unknown origin (FUO) with unexplained cytopenias, even in adults. The present case had a delay of 12 months before the diagnosis of HLH, and even we suspected only on the basis of haemophagocytosis in the bone marrow. The present case also illustrates that all the secondary HLH may not be fatal without early treatment.

References

- 1.Janaka GE, Shneider EM. Modern management of children with hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Br J Haematol. 2004;124:4–14. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2003.04726.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Feldmann J, Callebut I, et al. Munc13-4 is essential for cytolytic granules fusion and is mutated in form of familial phagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Cell. 2003;115:461–473. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00855-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Henter JI, Arico M, et al. HLH-2004: diagnostic and therapeutic guidelines for hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007;48(2):124–131. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Henter JI, Elinder G, et al. Incidence in Sweden and Clinical features of familial hemophagocytic lymohohistiocytosis. Acta Paediatr Scand. 1991;80(4):428–435. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1991.tb11878.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Janka GE. Familial hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Eur J Pediatr. 1983;140(3):221–230. doi: 10.1007/BF00443367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ramchandra B, Balasubramanian S, et al. Profile of Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in children in a tertiary care hospital in India. Indian Paediatr. 2011;48:31–35. doi: 10.1007/s13312-011-0020-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pramanik S, Pal P, et al. Reactive hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Indian J Paediatr. 2009;76(6):643–645. doi: 10.1007/s12098-009-0123-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bakshi S, Pautu JL. EBV-associated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis with spontaneous regression. Indian Paediatr. 2005;42:1253–1255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chandra SR, Syamlal S, et al. An interesting case of hemiplegia in a child. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 2007;10:49–51. doi: 10.4103/0972-2327.31486. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mathew LG, Cherian T, et al. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis-case series. Indian Pediatr. 2000;37(5):526–531. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Agarwal D, Gupta R, et al. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in a B-cell lymphoproliferaltive disorder: report of rare association. Indian J Hematol Blood Transfus. 2010;26(2):74–76. doi: 10.1007/s12288-010-0031-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sashidharan PK, Prashanti Varghese C, et al. Primary hemophagocytic syndrome in a young girl. Natl Med J India. 2011;24(1):19–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]