Abstract

A case of acute sigmoid volvulus in a 14-year-old adolescent girl presenting with acute low large bowel obstruction with a background of chronic constipation has been presented. Abdominal radiograph and CT scan helped in diagnosis. She underwent emergency colonoscopic detorsion and decompression uneventfully. Lower gastrointestinal contrast study showed very redundant sigmoid colonic loop without any transition zone and she subsequently underwent elective sigmoid colectomy with good outcome. The sigmoid volvulus should be considered in the differential diagnosis of paediatric acute abdomen presenting with marked abdominal distention, absolute constipation and pain but without vomiting. Plain abdominal radiograph and the CT scan are helpful to confirm the diagnosis. Early colonoscopic detorsion and decompression allows direct visualisation of the vascular compromise, assessment of band width of the volvulus and can reduce complications and mortality. Associated Hirschsprung's disease should be suspected if clinical and radiological features are suggestive in which case a rectal biopsy before definitive surgery should be considered.

Background

In children, midgut volvulus associated with congenital midgut malrotation or its variants with internal hernia and segmental volvulus following postoperative adhesions are the commonest strangulating lesions commonly seen.1 Acute gastric volvulus may be seen associated with congenital diaphragmatic anomalies.2 Large bowel volvulus is rare and only a few cases have been reported in children.3–6Sigmoid volvulus is a classic disease of the elderly, is an uncommon condition seen in children and is hardly ever considered as a differential diagnosis in acute abdomen in this age group. We wish to report an adolescent girl in whom emergency colonoscopic detorsion and decompression was successfully achieved which has not been described earlier in children.

Case presentation

A 14-year-old girl from a resident care home presented with marked degree of gaseous abdominal distention, lower abdominal pain and absolute constipation of 2 days duration. This was associated with reduced appetite and not being herself. She had background of acquired microcephaly, central motor disorder with hypotonia and brisk deep tendon reflexes, severe learning disability, repetitive hand movements, one episode of suspected seizure with febrile illness, chronic constipation and iron deficiency anaemia for which she was on iron supplements.

She was generally unwell with pulse rate of 134 beats per minute, respiratory rate of 18/minute and temperature of 38.4°C on admission. Her abdomen was soft and diffusely distended and tympanic on percussion. The distension was more marked peripherally. No mass was palpable. There were no signs of peritonitis and rectal examination revealed a completely empty rectum.

Investigations

Urine dipstick was normal. Complete blood count showed haemoglobin 112 g/L, white cell count 18.8×109/L, neutrophils 15.2×109/L, platelets 371×109/L and biochemical profile including renal, liver and bone profiles were within normal limits apart from potassium being 3 mmol/L. Blood gases showed pH 7.48, pCO2 5 kPa, pO2 9.5 kPa, lactate 0.8 mmol/L, base excess +4.1 and bicarbonate 28.1 mmol/L.

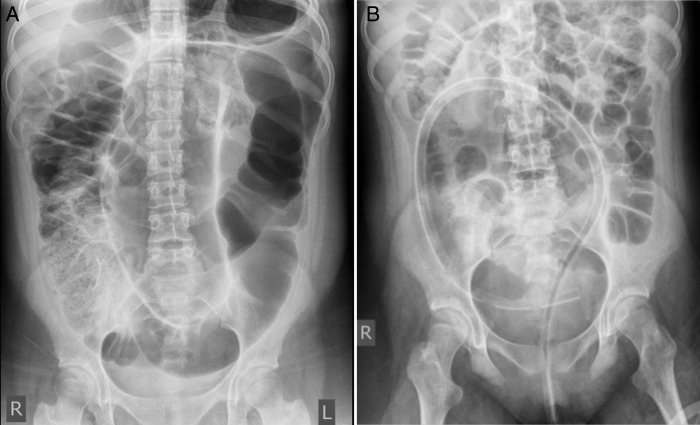

Abdominal radiograph showed characteristic very much dilated inverted U loop or classic coffee bean appearance of the distal large bowel extending from pelvis to the left hypochondrium suggestive of sigmoid volvulus (figure 1A). Heavy faecal loading of the right colon and caecum was seen and there was no suggestion of free intraperitoneal air on erect chest radiograph. This got fully deflated following sigmoidoscopic devolvulus and decompression satisfactorily (figure 1B).

Figure 1.

(A) Abdominal radiograph at presentation. (B) Postcolonoscopic reduction.

An urgent abdominal computerised tomogram showed grossly dilated large bowel loops showing bird beak-like narrowing of the sigmoid colon formed by tapering of the converging sections of the looped obstruction at the site of the volvulus with proximal colonic dilation (figure 2A, distal portion of volvulus; B–E, bird beak-like volvulus area; F, grossly dilated proximal colon) and whirl sign suggestive of sigmoid volvulus due to twisted sigmoid colon and mesentery best seen on the coronal examination (figure 3 top: coronal section showing whirl sign and bottom: sagittal sections). There was free fluid within the pelvis and abdomen but no evidence of dilated small bowel loops or free intraperitoneal gas.

Figure 2.

Abdominal CT scan: cross-section. Note long twist from pelvis to lower abdomen.

Figure 3.

Abdominal CT scan: coronal and sagittal views confirming sigmoid volvulus.

Differential diagnosis

At presentation acute abdomen due to catastrophic bowel twist in general and large intestinal volvulus with or without perforation was contemplated clinically but after plain abdominal radiograph the possibility of sigmoid volvulus was nearly certain due to typical appearance and CT scan confirmed it and ruled out perforation and peritonitis.

Treatment

After confirmation of diagnosis and initial resuscitation with intravenous fluids and antibiotics, she underwent colonoscopic examination with a plan to proceed for detorsion of acute sigmoid volvulus and decompression of proximal dilated colon if possible.

Colonoscopy showed a closed loop at the rectosigmoid junction, mucosal congestion, oedema and ulceration and signs of ischaemia at the site of volvulus.

At colonoscopy, on entering the rectum, apart from some degree of venous engorgement, the rectal mucosa was otherwise normal. The volvulus was identified at about 15 cm from the anal verge (figure 4A). The scope was passed through the twist fairly easily with minimal pressure (figure 4B). Whitish superficial mucosal patches were seen in the mucosa around the distal end of the volvulus probably representing superficial mucosal necrotic changes (figure 4C). On entering the proximal part of the sigmoid colon a significant amount of gas escaped down through the volvulus into the rectum (figure 4D). Faecal liquid material was further aspirated. This led to significant deflation of the sigmoid and descending colon and resulted in detorsion of the twisted colon. This allowed further examination of the twisted colon which revealed the volvulus to have involved about 10 cm of the sigmoid colon. Furthermore, it showed quite a large ulcerated mucosal patch involving about 25% of the circumference of the proximal part of the volvulus. The ulcerated area still appeared mucosal and covered with necrotic whitish mucosa (figure 4E). The descending colon was markedly dilated but with normal looking mucosal lining. The colonoscope was inserted up to a length of about 80 cm. A colonic tube with multiple holes at the distal end was inserted, the tip of which was at about the splenic flexure and was left in situ (figure 4F). Further examination of the abdomen at this stage revealed that it was fully deflated and not distended anymore.

Figure 4.

Colonoscopic views of the distal and proximal ends of the sigmoid volvulus.

She subsequently underwent lower gastrointestinal contrast study which showed redundant sigmoid colonic loop but there was no transition zone to suggest any associated Hirschsprung's disease (figure 5A: antero-posterior film and B: oblique film). She experienced similar symptoms in 2 days period. She had colonic preparation and underwent sigmoid colectomy from the junction between descending colon to peritoneal reflection uneventfully via a small left-sided smiling incision. A long, redundant sigmoid colon was found with an enlarged mesentery, but no signs of transmural necrosis were present. Sigmoid resection and a primary anastomosis were performed.

Figure 5.

Lower gastrointestinal contrast showing redundant long loop of sigmoid colon.

Outcome and follow-up

Resected segment of sigmoid colon measured 18.5 cm in length and 5.2 cm in maximum diameter. The serosal surface showed dusky discolouration. The wall was slightly thickened. The mucosal surface appears predominantly normal. Microscopic examination of sections showed mild crypt architectural distortion and mild patchy increase in lamina propria cellularity. The muscularis propria was thickened and there was mild patchy mural chronic inflammation. Congested blood vessels were noted within the submucosal and subserosal area. Close to one of the resection margins there were foci of mucosal ulceration with adjacent lamina propria and submucosal fibrosis. There was no evidence of Hirschsprung's disease, neuronal intestinal dysplasia or neoplasia. These appearances were in keeping with a clinical diagnosis of volvulus showing ischaemic complications.

Her postoperative period was uneventful and she made smooth and steady recovery. At 6-month follow-up she is asymptomatic and requires senna and lactulose as her regular laxatives.

Discussion

Sigmoid volvulus, a disease of elderly is third common cause of colonic obstruction in that age group, neoplasia being the number one and diverticulitis with stricture being the next common cause. It occurs when a redundant sigmoid loop rotates around its narrow, elongated mesentery, producing lymphovascular congestion and obstruction of the affected segment, followed by rapid distention of the closed loop. Although the underlying mechanism is long sigmoid loop with long and free sigmoid mesocolon; there are certain predisposing conditions eventually leading to volvulus with varying degree vascular compromise at the site of twist.

Among the large bowel volvulus, sigmoid colon volvulus is the commonest (60–85%) followed by caecal and transverse colon due to their redundancy and mobility in that order. It is twice more common in males, commonly seen between 50 and 70 years of age. The other precipitating factors include malrotation, Hirschsprung's disease, anorectal malformation, chronic constipation, use of laxatives, diabetes, neurodevelopmental or psychiatric disorders, postoperative peritoneal adhesions, chronic inflammatory disease and Chagas disease.

The clinical presentation varies with the degree of twist, close loop obstruction and strangulation. Clinical presentation varies from acute strangulating large bowel obstruction with perforation and peritonitis to that of chronic and recurrent episodes of abdominal colic and distention depending on the speed and degree of twist and plain radiographs and CT scan helps in establishing the diagnosis. In essence it is a mechanical problem and clinical presentation together with radiological findings are helpful but the laboratory studies may be normal. Barium enaema often confirms or suggests the diagnosis, and should be performed under fluoroscopic control; a ‘twisted-taper’ or ‘bird’s-beak’ configuration of the twisted colon is characteristic.

Salas et al6 has reported their experience with paediatric sigmoid volvulus. The median age at presentation was 7 years, ranging from 4 h to 18 years. Boys-to-girls ratio being 3.5 to 1. Presentation was either acute or recurrent. In acute cases, the mean duration of symptoms was 1.5 days. In recurrent cases, the chronic and intermittent episodes of pain had been present, on average, for 1 year. The most common symptoms were abdominal pain that is relieved by passage of stool or flatus, abdominal distention and vomiting. Radiological evaluation often reveals colonic dilation. The most common associated conditions included Hirschsprung’s disease and imperforate anus.

It is possible for sigmoid volvulus to resolve spontaneously, initial management begins with fluid resuscitation and antibiotics, followed by radiological plain and contrast imaging studies. Plain films and CT scan help to establish the diagnosis. The management is staged one initial radiological interventional with contrast enaema reduction and endoscopic detortion and stabilisation followed later in 2–3 days to definitive resection of sigmoid with primary colorectal anastomosis.7

Radiological interventional barium enaema detorsion of the sigmoid volvulus is described in the centres where emergency sigmoidoscopic examination is not available. Endoscopic modalities include proctosigmoidocolonoscopy and decompression by rectal tube. In adults, interventional endoscopic percutaneous sigmoid colopexy is described.8 Subsequent definitive operative management most commonly consists of laparoscopic or operative sigmoidectomy with excellent prognosis. Primary urgent surgery may be required in perforation and peritonitis cases with high morbidity and mortality due to associated septicaemia and multiple organ failure.

Learning points.

The sigmoid volvulus is rare in children but should be considered in the differential diagnosis in an adolescent with a background of chronic constipation who present acutely with marked abdominal distention, absolute constipation and pain but without vomiting.

Plain abdominal radiograph can help suspect the diagnosis and the CT scan can confirm the diagnosis and may detect associated complications of vascular compromise and perforation.

Emergency colonoscopic reduction and decompression of proximal dilated colon allows not only emergency to tide over but do further investigations and prepare for elective definitive surgery.

Early colonoscopic detorsion and decompression allows direct visualisation of the vascular compromise, assessment of band width of the volvulus and can reduce complications and mortality.

Associated Hirschsprung's disease should be suspected in younger children if clinical symptoms of the delayed passage of meconium at birth followed by progressive constipation associated with abdominal distention and failure to thrive is there, lower gastrointestinal contrast shows a transition zone in which case a rectal biopsy before definitive surgery should be considered.

Footnotes

Contributors: All the authors have made substantial contributions to the conception and design of this paper, search of the literature, the acquisition, analysis and interpretation of the data, drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content, and to the final approval of the version to be published.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Patel RV, Lawther S, Starzyk B, et al. Neonatal obstructed Treitz's hernia with abdominal cocoon simulating volvulus neonatorum. BMJ Case Rep 2013;2013:pii: bcr2013009950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Patel RV, More B, Sinha CK, et al. Gastric volvulus: a rare association with hyperamylasemia. J Pediatr Surg Case Rep 2013;1:47e49 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Patel RV, Njere I, Govani D, et al. Paediatric caecal volvulus with perforation and faecal peritonitis. BMJ Case Rep 2014;2014:pii: bcr2014205511 (submitted for publication). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sharma D, Parameshwaran R, Tushar Dani T, et al. Malrotation with transverse colon volvulus in early pregnancy: a rare cause for acute intestinal obstruction. BMJ Case Rep 2013. 10.1136/bcr-2013-200820 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nuevo SP, Macías Robles MD, Delgado Sevillano R, et al. Absolute constipation caused by sigmoid volvulus in a young man. BMJ Case Rep 2013. 10.1136/bcr-2012-008260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Salas S, Angel CA, Salas N, et al. Sigmoid volvulus in children and adolescents. J Am Coll Surg 2000;190:722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oren D, Atamanalp SS, Aydinli B, et al. An algorithm for the management of sigmoid colon volvulus and the safety of primary resection: experience with 827 cases. Dis Colon Rectum 2007:489–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pinedo G, Kirberg A. Percutaneous endoscopic sigmoidopexy in sigmoid volvulus with T-fasteners: report of two cases. Dis Colon Rectum 2001;44:1867–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]