Abstract

Background & Aims

Patients with Lynch syndrome carry germline mutations in single alleles of genes encoding the MMR proteins MLH1, MSH2, MSH6 and PMS2; when the second allele becomes mutated, cancer can develop. Increased screening for Lynch syndrome has identified patients with tumors that have deficiency in MMR, but no germline mutations in genes encoding MMR proteins. We investigated whether tumors with deficient MMR had acquired somatic mutations in patients without germline mutations in MMR genes using next-generation sequencing.

Methods

We analyzed blood and tumor samples from 32 patients with colorectal or endometrial cancer who participated in Lynch syndrome screening studies in Ohio and were found to have tumors with MMR deficiency (based on microsatellite instability and/or absence of MMR proteins in immunohistochemical analysis, without hypermethylation of MLH1), but no germline mutations in MMR genes. Tumor DNA was sequenced for MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS2, EPCAM, POLE and POLD1 with ColoSeq and mutation frequencies were established.

Results

Twenty-two of 32 patients (69%) were found to have two somatic (tumor) mutations in MMR genes encoding proteins that were lost from tumor samples, based on immunohistochemistry. Of the 10 tumors without somatic mutations in MMR genes, 3 had somatic mutations with possible loss of heterozygosity that could lead to MMR deficiency, 6 were found to be false-positive results (19%), and 1 had no mutations known to be associated with MMR deficiency. All of the tumors found to have somatic MMR mutations were of the hypermutated phenotype (>12 mutations/Mb); 6 had mutation frequencies >200 per Mb, and 5 of these had somatic mutations in POLE, which encodes a DNA polymerase.

Conclusions

Some patients are found to have tumors with MMR deficiency during screening for Lynch syndrome, yet have no identifiable germline mutations in MMR genes. We found that almost 70% of these patients acquire somatic mutations in MMR genes, leading to a hypermutated phenotype of tumor cells. Patients with colon or endometrial cancers with MMR deficiency not explained by germline mutations might undergo analysis for tumor mutations in MMR genes, to guide future surveillance guidelines.

Keywords: colon cancer, MSI, genomic instability, dMMR

INTRODUCTION

Lynch syndrome is the most common inherited cause of colorectal and endometrial cancers, accounting for approximately 3% of these cases.1–4 Lynch syndrome is caused by germline mutations in the mismatch repair (MMR) genes; MLH1, MSH2 (and EPCAM), MSH6 and PMS2 followed by a second hit to the other allele at some point during the patient’s lifespan leading to cancer development. The MMR system functions to correct mistakes in DNA replication and once impaired, cells accumulate an abundance of mutations, which is believed to lead to malignant transformation and eventually tumor formation with a hypermutated phenotype.5 This is manifested by microsatellite instability (MSI) and absence of one or more of the four MMR proteins on immunohistochemical staining.

Universal tumor screening for Lynch syndrome among all newly diagnosed colorectal cancers has been recommended by the CDC workgroup, Evaluation of Genomic Applications in Practice and Prevention, using either the MSI or immunohistochemical staining for the four mismatch repair proteins.6 As a result, 71% of NCI designated Comprehensive Cancer Centers, 36% of Community Hospital Comprehensive Cancer Programs and 15% of Community Hospital Cancer Programs are now performing reflexive screening for Lynch syndrome with 38% of all surveyed hospitals testing all colorectal cancer cases.7

One of the major challenges when performing universal screening are cases where tumors have absent MMR proteins on immunohistochemistry and/or MSI but no evidence of germline mutations. Acquired hypermethylation of the MLH1 gene has long been known to be responsible for about 80% of cases where MLH1/PMS2 is missing so this is generally ruled out prior to germline testing of MLH1. Of cases with MSH2/MSH6 missing on immunohistochemistry for whom no germline MSH2 or MSH6 mutation had been identified, germline mutations in EPCAM and an inversion of MSH2 (exons 1–7) were found to explain 20–25% and 5%, respectively.8,9 However, this still leaves many cases without a germline mutation unexplained. These patients have been described as having Lynch-like syndrome, and this was seen in 2.5% of all patients on the prospective Spanish EPICOLON10 and in 3.9% of all patients on the Columbus Lynch syndrome study1,2 (unpublished data). Potential explanations for these cases include germline mutations not detected by current screening methods, bi-allelic tumor DNA mutations in MMR genes, somatic mosaicism for a MMR gene mutation, or false positive screening test results. The results leave a dilemma for genetic counseling and often these patients and their relatives are advised to follow rigorous Lynch syndrome screening protocols until further information can be obtained.11 In more recent years, it has become evident that some of these patients may have tumors with bi-allelic somatic DNA mutations and might therefore not need rigorous Lynch syndrome cancer screening.12,13 Testing for MMR mutations in tumor DNA has not been performed commonly in the past because tumor DNA is often of poor quality with DNA fragmentation and can furthermore be mixed with DNA from adjacent normal cells. Next-generation sequencing has revolutionized gene sequencing and has made it more feasible to test tumor DNA for mutations.

The objective of this study was to look for somatic mutations in tumor DNA of patients from the Columbus Lynch syndrome study, and the more recent ongoing Ohio Colorectal Cancer Prevention Initiative (OCCPI), that had MMR deficient and/or MSI tumors with no apparent germline mutations and no MLH1 promoter hypermethylation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

Patients from the previously published Columbus Lynch syndrome study1,3 and the ongoing state-wide prospective Lynch syndrome screening study in Ohio (OCCPI)14 were included. Both studies included patients with newly diagnosed colorectal and endometrial cancer, regardless of age at diagnosis or family history. The research protocol and consent form were approved by the institutional review board at each participating hospital, and all patients provided written informed consent. Patients with MSI-H tumors and/or abnormal immunohistochemistry without detectable germline mutations, were selected based on being suspicious for having Lynch syndrome and having tumor DNA available for testing. MMR gene mutation analysis was performed on their tumor.1,2 Patient charts were accessed and family history, patient and tumor characteristics were documented.

MSI, Immunohistochemistry and MLH1 hypermethylation testing

For patients on the Columbus Lynch syndrome study, DNA was extracted from paraffin-embedded tumor tissue and blood and immunohistochemistry, MSI testing, MLH1 hypermethylation testing, and germline genetic testing (sequencing and multiplex ligation probe assay) for the four MMR genes was performed as previously described.1–4 For patients on the OCCPI study, H&E stained slides of the tumors were reviewed by a pathologist, and areas of tumor containing over 30% viable tumor cells were marked for macrodissection, to enrich tumor DNA. Tissue sections were scraped off from unstained glass slides using QiaAmp DNA micro kit (Qiagen) following manufacturer's instructions after overnight digestion with 20 µL of Proteinase K. Microsatellite testing was performed using 5 mononucleotide markers (BAT-25, BAT-26, NR-21, NR-24 and MONO-27) testing both tumor tissue and unaffected tissue with the Promega fluorescent multiplex PCR-kit (Promega, Madison, Wisconsin, USA). Results were considered MSI-high when an allelic shift was present in the tumor compared to the unaffected tissue in 2 or more markers tested and MSI-low when instability was shown by only one marker. Tumor tissue was stained for MLH1 (Novacastra, NCL-L-MLH-1), MSH2 (Calbiochem, NA27), MSH6 (Epitomics, AC-0047) and PMS2 (BD Pharmingen, 556415) proteins with immunohistochemistry if performed at OSU but some tumors had immunohistochemistry performed at outside hospitals. The 5’ part of the promoter region of MLH1 was assessed for methylation. DNA was modified with sodium bisulfite and the bisulfite treated DNA was amplified by Pyrosequencing.

Germline and somatic mutation analysis

Three micrograms of tumor DNA and 3 micrograms of germline DNA isolated from peripheral blood lymphocytes were shipped to University of Washington for analysis. Tumor and blood DNA testing was performed using the ColoSeq next-generation sequencing method that has been previously described15. Briefly, ColoSeq is a clinical diagnostic assay for hereditary colon cancer that detects single nucleotide, indel and deletion/duplication mutations in 19 genes including MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS2, EPCAM, POLE and POLD1. (http://tests.labmed.washington.edu/COLOSEQ). The assay uses paired-end sequencing on the Illumina HiSeq 2500 instrument to sequence all exons, introns, and flanking sequences at >300× average coverage. Mosaic mutations are detectable by this methodology when present in as little as 2% of the DNA.16 Single nucleotide variant and indel calling was performed through the GATK Universal Genotyper using default parameters and using VarScan v2.3.2.17 Deletion/duplication analysis was performed using CONTRA v2.0.318 with customized scripts to allow accurate detection of events at exon-level resolution. PINDEL version 0.2.419 was used to identify tandem duplications and indels greater than 10bp in length. Structural variants are identified using CREST v1.0 and BreakDancer v1. Loss of heterozygosity (LOH) was determined by analysis of the variant allele fraction (VAF). LOH was called when: 1) the VAF for a mutation was >80% higher (~2 times) than the average somatic mutation VAF in the tumor, and 2) corroborated by analysis of shifts in expected VAF among germline polymorphisms within the same gene region. Possible LOH was defined as VAF between 40–80% higher than the average somatic mutation VAF. Tumor BRAF mutations were determined using a targeted next generation deep sequencing approach which has been previously described.20

Total mutation counts were estimated by looking at the total number of mutations found by the ColoSeq platform in exons and introns and comparing the frequency in tumor DNA versus blood germline DNA. If germline DNA was not available, mutations were filtered if they had an allelic fraction > 0.06 and no hits in the following databases: 1000 genomes, exome variant server, dbSNP.

Phenotypic microsatellite instability was assessed directly from ColoSeq next-generation sequencing data using mSINGS (MSI by NGS).21 This method evaluated up to 146 mononucleotide microsatellite loci that are captured by ColoSeq in both blood and tumor samples. For each microsatellite locus, the distribution of size lengths were compared to a population of normal controls. Loci were considered unstable if the number of repeats is statistically greater than in the control population. A fraction of >0.20 (20% unstable loci) was considered MSI-high by mSINGS based on validation with 324 tumor specimens, in which 108 cases had MSI-PCR data available as a gold standard.

Ten somatic MMR gene mutations found by ColoSeq were randomly selected and confirmed by Sanger sequencing. Genomic DNA (20 ng) was amplified by PCR using AmpliTaq Gold DNA Polymerase (Applied Biosystems). PCR products were sequenced using ABI Prism BigDye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Kit version 3.1 and the Applied Biosystems 3730 DNA Analyzer (PE Applied Biosystems). All primers and PCR conditions are available upon request.

Screening for large rearrangements

Unexplained tumors with MSH2 absent on immunohistochemistry were also screened for inversion of exons 1–7 of the MSH2 gene with methods previously described by Rhees et al.9

Mutation Interpretation

A 5-tiered scheme for classifying MMR mutations was recently published22 and was used to classify the MMR mutations found (class 5=pathogenic; class 4=likely pathogenic; class 3=uncertain; class 2=likely not pathogenic; class 1=not pathogenic). If mutations were not classified by INSIGHT, their impact on protein sequence was described. Cases were considered solved if: 1) Two pathogenic or likely pathogenic mutations were identified (mutations identified as class 4 or 5 or predicted to result in protein truncation); or 2) One pathogenic or likely pathogenic mutation was identified with associated LOH. Cases were considered possibly solved if only one pathogenic or likely pathogenic mutation was identified with possible LOH. Cases were considered not explained if only one pathogenic or likely pathogenic mutation was identified without LOH, if only class 1–2 variants were detected, or if no mutations were identified in the MMR genes.

Statistical Methods

Descriptive statistics (median with quartiles (Q) for age and mean with standard deviation for continuous variables and frequency for categorical variables) were provided to describe the patient population. Student’s t-test was used to compare continuous variables. The SPSS statistical software, version 21 was used.

RESULTS

Patient characteristics

A total of 32 patients with either colorectal or endometrial cancer (see Table 1 for patient characteristics) were screened for somatic mutations using ColoSeq, 22 from the Columbus Lynch syndrome study (21% of unexplained colorectal cancer cases and 38% of unexplained endometrial cancer cases) and 10 from the OCCPI (100% of unexplained cases on the study; see Supplemental figures 4 and 5 for screening outcomes). All of these patients had previously tested negative for MMR germline mutations by Sanger sequencing (except for case #1574), MLPA (including EPCAM), and MLH1 hypermethylation negative if MLH1 was missing on immunohistochemistry. Tumors had concordant results on immunohistochemistry and MSI testing in all cases except for 5 with abnormal immunohistochemistry and microsatellite stability, 2 cases with abnormal immunohistochemistry and low MSI and 1 case with normal immunohistochemistry and high MSI.

Table 1.

Patient and tumor characteristics

| Patient # | Age at dx, gender |

Cancer site | Histology | Grade | Stage | Other cancers | Fulfilled Amsterdam II or revised Bethesda criteria |

Solved |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 54 | 62 F | R Colon | Adenocarcinoma | 1 | I | Lymphoma, 60 yo | No | False + screening |

| 79 | 63 M | R Colon | Adenocarcinoma w/mucinous features | 2 | IIIB | Prostate cancer | No | Yes |

| 263 | 47 F | Uterus | Endometrioid adenocarcinoma | FIGO gr 3 | IIIC2 | None | No | Possibly |

| 688 | 71 M | R Colon | Mucinous/signet ring adenocarcinoma | 3 | IIIB | None | No | Possibly |

| 841 | 51 M | R Colon | Mucinous adenocarcinoma | 2 | IIIB | None | Bethesda | Yes |

| 956 | 62 F | Uterus | Carcinosarcoma | 3 | IB | None | No | Yes |

| 1004 | 64 F | Uterus | Endometrioid adenocarcinoma | FIGO gr 2 | IA | None | No | Yes |

| 1059 | 34 M | R Colon | Adenocarcinoma | 2 | IIIB | None | Bethesda | Possibly |

| 1228 | 54 F | Uterus | Endometrioid adenocarcinoma | 2 | IA | None | No | Yes |

| 1410 | 65 M | R Colon | Mucinous adenocarcinoma | 1 | IIA | None | No | Yes |

| 1423 | 34 F | R Colon | Adenocarcinoma | 3 | IIA | None | Amsterdam, Bethesda | Yes |

| 1546 | 33 M | R Colon | Mucinous adenocarcinoma | 2 | IIIC | None | Bethesda | Yes |

| 1574 | 47 M | R Colon | Adenocarcinoma w/mucinous features | 2 | IIIB | None | Bethesda | Yes |

| 55379 | 41 F | Uterus | Clear cell adenocarcinoma | FIGO gr 3 | IIIC1 | None | No | Yes |

| 55380 | 47 M | Rectum | Adenocarcinoma | 2 | IIA | None | Amsterdam, Bethesda | Yes |

| 56834 | 51 F | Uterus | Endometrioid adenocarcinoma | FIGO gr 1 | IA | None | No | Yes |

| 60620 | 52 F | Uterus | Endometrioid adenocarcinoma | FIGO gr 1 | IB | None | No | Yes |

| 63123 | 48 F | R colon | Adenocarcinoma | NR | IV | None | Bethesda | False + screening |

| COL-24 | 47 F | Uterus | Endometrioid adenocarcinoma | FIGO gr 1 | IA | None | No | Yes |

| COL-25 | 37 F | R Colon | Adenocarcinoma with mucinous features | 2 | IIIB | None | Bethesda | Yes |

| COL-26 | 80 F | R Colon | Adenocarcinoma | 2 | I | Basal cell carcinoma, 80 yo | No | Yes |

| COL-27 | 64 F | R Colon | Adenocarcinoma | NR | IIA | None | No | Yes |

| COL-28 | 62 F | Uterus | Endometrioid adenocarcinoma | FIGO gr 1 | IA | None | No | Yes |

| COL-29 | 66 F | L Colon | Adenocarcinoma | NR | IVA | None | No | False + screening |

| COL-30 | 65 M | R Colon | Adenocarcinoma | 2 | IIIA | Prostate cancer, 50 yo | No | Yes |

| COL-31 | 52 F | Uterus | Endometrioid adenocarcinoma | FIGO gr 1 | IB | None | No | False + screening |

| COL-32 | 65 F | Uterus | Endometrioid adenocarcinoma | FIGO gr 1 | IB | Basal cell carcinoma, 42 yo | No | False + screening |

| COL-33 | 65 M | Rectosigmoid | NR | 2 | I | None | Amsterdam, Bethesda | No |

| 968 | 81 F | Uterus | Endometrioid adenocarcinoma | FIGO gr 3 | IB | None | No | Yes |

| 58429 | 71 F | Uterus | Mixed cell adenocarcinoma | FIGO gr 3 | IB | None | No | Yes |

| 217 | 86 F | Uterus | Endometrioid adenocarcinoma | FIGO gr 2 | IB | None | No | False + screening |

| 1659 | 57 F | L colon | Adenocarcinoma | 2 | IIA | None | No | Yes |

Dx=diagnosis; F=female; FDR=first degree relative; gr=grade; L=left; M=male; NEC=neuroendocrine; NOS=not otherwise specified; NR=not reported; R=right; yo=year old.

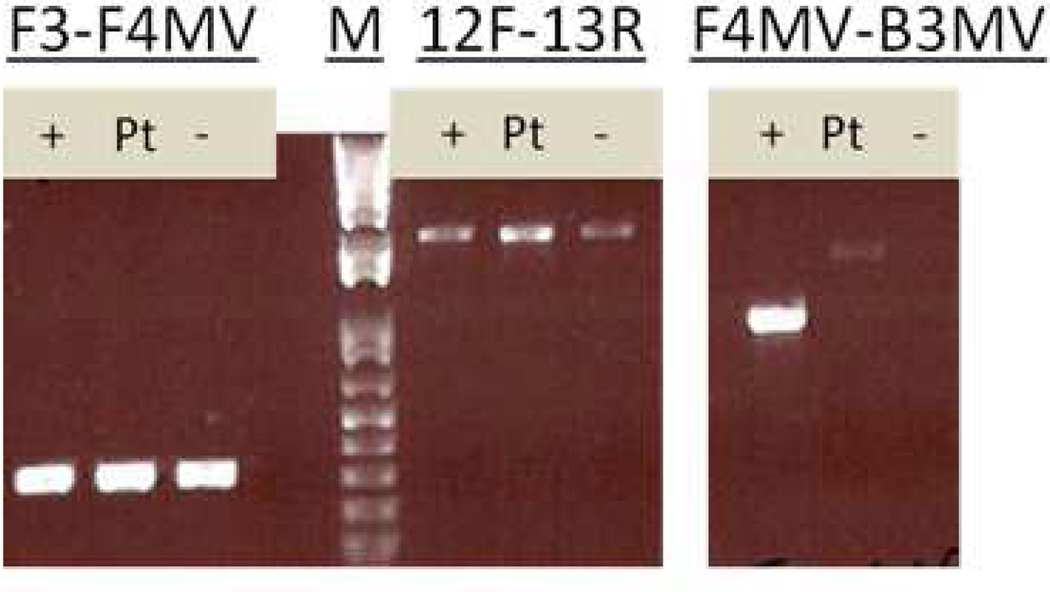

Gene sequencing

Out of the 32 patients, 22 (69%) were found to have two somatic mutations explaining their findings on MSI/immunohistochemistry testing, 3 (9%) patients were found to have changes possibly explaining MSI/immunohistochemistry testing (see Table 2 for DNA sequencing findings) and 6 (19%) patients were found to have had initial false positive screening tests (see below). Case #COL-33 was only found to have one mutation in MSH2 without associated LOH and remained unexplained. In 12 cases (10 MSH2, 1 MSH6, 1 PMS2), two different heterozygous mutations were found in the same gene. In 9 cases (7 MLH1, 1 MSH2, 1 MSH6), a single mutation was found in association with LOH. All 7 cases of somatic MLH1 mutations were accompanied by LOH, while 2 different heterozygous mutations were found in 9 out of 12 cases involving somatic MSH2 mutations. Less than one third of the mutations were classified by InSiGHT.22 Of the pathogenic mutations not classified by InSiGHT, most were frameshift mutations, mutations anticipated to impact splicing, large deletions and nonsense mutations. Case #1574 was known to have a germline mutation in PMS2 but was submitted for ColoSeq because it had an unusual immunohistochemistry staining pattern with both MSH6 and PMS2 absent on immunohistochemistry (in cases of PMS2 germline mutations, immunohistochemistry would usually only show PMS2 missing). ColoSeq revealed 2 somatic mutations in MSH6 in this case along with the germline mutation (also seen in the tumor) and a secondary somatic mutation in PMS2, explaining the staining. Blood samples were tested for germline mutations by ColoSeq in all cases except #1059 (insufficient DNA) and no pathogenic germline mutations were found except in case #1574 where Coloseq confirmed the already known mutation in PMS2. Ten mutations found by ColoSeq were chosen randomly and all of them were confirmed by using PCR and Sanger sequencing (see Figure 1 and Table 2). The MSH2 exon 1–7 inversion was investigated in eight tumor samples with MSH2/MSH6 absent on immunohistochemistry. A faint specific band was seen in patient samples with the F4MV-B3MV primers (which detect the 3’ breakpoint) which was not consistent with the band seen in the positive control sample. All eight samples were therefore negative for the inversion (see Figure 2). Only one out of 32 tumors had a BRAF V600E mutation (case #54) which was shown to have had false negative MLH1 hypermethylation testing on repeat testing (see below).

Table 2.

Results from IHC, MSI testing and tumor and germline DNA sequencing by next generation sequencing

| Patient # |

MSI | IHC absent protein(s) |

Mutation #1 | Pathogenicity1 | Mutation #2 | Pathogenicity1 | Solved |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 54 | Low | MLH1 | None | None | False + screening | ||

| 79 | High | MSH2/6 | MSH2 c.1832delT2 | Fs | MSH2 c.2074G>T2 | Nonsyn SNV | Yes |

| 2633 | High | MSH2/6 | MSH2 del exon 1–6 | Large del | MSH2 possible LOH | Possibly | |

| 6884 | High | MSH2/6 | MSH2 c.1229delG2 | Fs | MSH2 possible LOH | Possibly | |

| 8415 | High | MLH1/PMS2 | MLH1 c.613dup2 | Fs | MLH1 LOH | Yes | |

| 956 | High | MSH2/6 | MSH2 c.942+3A>T | Class 5 | MSH2 c.1787delA | Fs | Yes |

| 1004 | High | MSH2/6 | MSH6 c.930dupT | Fs | MSH6 LOH | Yes | |

| 1059 | High | MSH2/6 | del MSH2/MSH6 locus | Large del | MSH2/MSH6 possible LOH | Possibly | |

| 1228 | High | MLH1/PMS2 | PMS2 c.1687C>T | Stopgain | PMS2 c.199G>T | Stopgain | Yes |

| 1410 | High | MLH1/PMS2 | MLH1 c.981_982delinsTT2 | Stopgain SNV | MLH1 LOH | Yes | |

| 1423 | High | MSH2/6 | MSH2 c.2131C>T2 | Class 5 | MSH2/MSH6 copy loss | Large del | Yes |

| 1546 | High | MSH2/6 | MSH2 c.943-1G>A2 | Class 4 | MSH2 c.1086_1151del642 | Nonfs del | Yes |

| 1574 | High | MSH6/PMS2 |

MSH6 c.1609A>G PMS2 c.137G>T6 |

Nonsyn SNV Class 4 |

MSH6 c.3261dup (class 5) PMS2 c. 2175-3C>G PMS2 c.1075T>C |

Stop Splicing Syn SNV |

Yes |

| 55379 | High | MLH1/PMS2 | MLH1 c.306+1G>A2 | Class 4 | MLH1 LOH | Yes | |

| 55380 | High | MLH1/PMS2 | MLH1 c.1963_1964dupTA | Fs | MLH1 LOH | Yes | |

| 56834 | High | MSH2/6 | MSH2 c.1144delC | Fs | MSH2 c.490_508del | Fs | Yes |

| 60620 | High | MSH2/6 | MSH2 c.1147C>T | Class 5 | MSH2 del exon 3 | Large del | Yes |

| 63123 | High | None | None | None | False + screening | ||

| COL-24 | High | MSH2/6 | MSH2 c.1294_1298del | Fs | MSH2 c.1203dupA | Fs | Yes |

| COL-25 | High | MLH1/PMS2 | MLH1 c.790+5G>A | Class 3 | MLH1 LOH | Yes | |

| COL-26 | High | MLH1/PMS2 | MLH1 c.979C>T | Stop | MLH1 LOH | Yes | |

| COL-27 | High | MSH2/6 | MSH2 c.731dup | Fs | MSH2 c.2228C>T | Nonsyn SNV | Yes |

| COL-28 | Stable | MSH6 | MSH6 del exon 7 | Large del | MSH6 c.3261del | Class 5 | Yes |

| COL-29 | Stable | PMS2 | None | None | False + screening | ||

| COL-30 | High | MLH1/PMS2 | MLH1 c.380G>A | Class 4 | MLH1 LOH | Yes | |

| COL-31 | Stable | MSH2/6 | None | False + screening | |||

| COL-32 | Stable | MSH2/6 | None | False + screening | |||

| COL-33 | High | MSH2/6 | MSH2 c.790C>T | Stopgain | None | No | |

| 968 | High | MSH2/6 | MSH2 c.1738G>T | Class 5 | MSH2 c.2018G>A | Nonsyn SNV | Yes |

| 58429 | High | MSH2/6 | MSH2 c.1738G>T | Class 5 |

MSH2 c.366+1G>A; MSH2 c.2405T>C; MSH2 c.895T>C |

Splicing; nonsyn SNV; nonsyn SNV |

Yes |

| 217 | Stable | MSH2 | None | None | False + screening | ||

| 1659 | Low | MSH2/6 | MSH6 c.3260_3261dup | Fs | MSH2/MSH6 copy loss | Large del | Yes |

Classified per INSIGHT criteria (where not available, impact on protein sequence is resulted);

Mutations confirmed by Sanger sequencing;

MSH6 c.3261delC (class 5) in tumor;

MLH1 c.2019delT2 (fs) in tumor;

MSH6 c.913A>T (nonsyn SNV) in tumor;

PMS2 mutation present in germline and tumor DNA.

Del=deletion; Fs=frameshift; Ins=insertion; Nonsyn=nonsynonymous; Syn=synonymous; SNV=single nucleotide variant; VUS=variant of unknown significance; LOH=loss of heterozygosity

Figure 1.

Confirmation of two mutations by Sanger sequencing on tumor DNA. Upper chromatogram from patient #688 (MLH1 c.2019delT (heterozygous)) and lower chromatogram from patient #841 (MLH1 c.613dup (hemi/homo)). Samples were sequenced with forward primers (available on request).

Figure 2.

PCR testing for MSH2 inversion with positive control (+), patient sample #688 (Pt) and negative control (−) with a 1-kb marker (M). Primers F3 and F4MV amplify a wild-type chromosome 2, F4MV and B3MV detect the 3’ breakpoint for the MSH2 inversion, primers and methods were previously described by Rhees et al.12 The 12F (exon 12 forward) and 13R (exon 13 reverse) primers were designed as controls to verify DNA integrity.

False positive screening results

Six cases were not explained by somatic mutations and did not have a hypermutated phenotype. All of them had discordant findings on immunohistochemistry and microsatellite testing. These cases had repeat immunohistochemistry and MSI testing done and in case #54, MLH1 hypermethylation testing was repeated. All these cases were found to have had false positive screening results (case #54 was MLH1 hypermethylated, case #63123 was microsatellite stable on repeat MSI-PCR and also microsatellite stable by mSINGS testing on ColoSeq (see supplementary table 3), case #COL-28, #COL-29, #COL-31 and #COL-32 all had intact MMR stains on immunohistochemistry repeat).

Age at diagnosis, tumor pathology and Amsterdam/Bethesda criteria

Eighteen patients had colorectal cancer and 14 patients had endometrial cancer. The median age of cancer diagnosis of the entire cohort was 59.5 years (Q1 47; Q3 65) and in the solved cases with two somatic mutations it was 57.0 years (Q1 47, Q3 64.5). The tumors with two somatic MMR mutations exhibited characteristics similar to what is seen in patients with MLH1 hypermethylated or Lynch syndrome associated tumors, i.e. colon cancers tended to be right-sided (14 out of 18) and mucinous (7 out of 18) and endometrial cancers to have endometrioid histologies (11 out of 14) (see Table 1). Contrary to Lynch syndrome-associated cancers, metachronous or synchronous cancers were not seen in our cohort.

Of the 22 patients with screening results explained by tumor MMR mutations only two (9%) met Amsterdam II criteria and six (27%) met revised Bethesda criteria (see Table 1). Interestingly, case #COL-33 was the only patient meeting both criteria whose cancer was not explained by a germline mutation or somatic tumor mutations. This patient is certainly an outlier in our series and could have an undetected germline MSH2 mutation.

Tumor mutation burden

Tumor mutation burden ranged from 0–773 mutations per megabase (Mb) per tumor (see Figure 3). Mutation burden was higher in tumors explained/possibly explained by somatic tumor MMR mutations than tumors that had false positive screening results (mean 152+/−199 mutations/Mb vs 10+/−11 mutations/Mb, p=0.095). All tumors with two somatic MMR mutations displayed a hypermutated (>12 mutations per Mb) or an ultramutated (>400 mutations per Mb) phenotype. Tumor mutation frequencies were the highest in tumors that also contained somatic mutations in POLE.

Figure 3.

Total mutation burden per megabase in tumor DNA detected by ColoSeq in exons and introns. White columns represent MSS tumors, black columns MSI tumors and diagonal columns represent tumors with POLE mutations. *Tumors with two somatic MMR mutations explaining screening test findings. #Tumors with MMR mutations possibly explaining screening test findings.

POLE mutations

Somatic mutations in the POLE DNA polymerase were found in 5 tumors. All of them displayed high microsatellite instability, abnormal immunohistochemistry staining and mutations in mismatch repair genes were found on analysis. Three of the tumors were endometrial cancers while 2 were colon cancers. In 3 cases (case #1228, #968, #58429) the mutation involved the exonuclease domain of POLE and these cases were all ultramutated (>400 mutations per Mb, see Figure 3).

DISCUSSION

In one of the largest population-based screening studies for Lynch syndrome in colorectal1 and endometrial cancer3, 3.9% of all screened patients had MMR deficient tumors that were not explained by germline mutations, leaving the treating physician and the patient unsure of the implications of an abnormal screening test. This study confirms that most of these cases can be explained by two somatic tumor mutations. The abnormal screening tests were explained by tumor MMR gene mutations in 69% of cases and another 9% were possibly explained by tumor MMR mutations found by next-generation sequencing. One case was not explained (single MSH2 mutation) but given the abnormal immunohistochemistry, MSI and the strong family history (meeting both Amsterdam and Bethesda criteria) this patient could have an undetected MSH2 germline mutation. The remainder of the cases (19%) had discordant findings on immunohistochemistry and microsatellite testing and were found to have had false positive screening results. Next generation sequencing has made it more feasible to screen tumor DNA for somatic mutations in patients who have abnormal Lynch syndrome screening. The results help guide patients as they will not require intensive life-long screening if they do not have Lynch syndrome.

This study is the first one to investigate mutations in all four MMR genes in tumor DNA in colorectal and endometrial cancer and to look at mutation burden in the context of MMR mutations in tumor DNA. Two recent studies reported somatic tumor mutations in 52%13 and 22%12 of all unexplained MMR deficient tumors. Mensenkamp et al. screened 25 MSI-positive tumors (with either MLH1 or MSH2 protein missing on immunohistochemistry) for somatic mutations and LOH by Sanger sequencing and ion semiconductor sequencing. A total of 13 tumors were found to have two plausible pathogenic somatic mutations and/or LOH.13,23 Sourrouille et al. utilized Sanger sequencing and detected somatic mutations in 4 out of 18 unexplained MMR-deficient tumors, one case of which had a mosaic mutation occurring in some but not all somatic cells.12 Few groups have studied the second hit to the MMR gene in patients with germline mutations and none of them used next generation sequencing for analysis.24–26 In our study, it is important to note that in the cases with two somatic MMR gene mutations, we cannot definitively prove that the mutations were in two different alleles (trans) and not on the same allele (cis). However, the evidence points to these mutations being in trans thus explaining the corresponding protein loss on immunohistochemistry, leading to MSI and a hypermutated phenotype. The tumors with one somatic MMR gene mutation associated with LOH clearly have damaging events to both alleles of the MMR gene. Somatic mosaicism cannot be completely ruled out but is unlikely as ColoSeq can detect mutations in as little as 2% of DNA.16 In the three cases that are possibly explained in our study, it was difficult to determine whether the mutations were associated with LOH. In all three cases, the tumors accumulated frequent mutations (range 38–126 per Mb) supporting the notion that the MMR gene mutations were pathogenic.

Interestingly, in all 7 cases of somatic MLH1 mutations, the mutations were associated with LOH. Some cases with LOH were associated with copy loss and in others there was not clear gene copy loss, despite clear LOH. Copy-neutral LOH is common in tumors, due to acquired uniparental disomy and is a likely mechanism for cases with LOH in which copy loss was not apparent. This mechanism deserves further study. In most cases with MSH2 mutations however, two heterozygous mutations affecting the same gene were seen. Our study results suggest that MLH1 may be more prone to LOH27 than MSH2.

The InSiGHT group recently undertook an enormous effort to classify the pathogenicity of MMR mutations and this has changed the classification of several known mutations.22 Some of the tumor mutations found in this study are consistent with hotspot mutations seen in Lynch syndrome such as the MSH2 splice site mutation (c.943+3A>T) in patient #956, frequently found to occur de novo in the germline.28 However, the majority of mutations found are not classified in InSiGHT. It is possible that tumor mutations happen in areas different from the inherited germline mutations which are conserved and passed on from generation to generation. Even so, most of the mutations found were frameshift mutations, large deletions or mutations leading to stop codons.

Of the eight cases with discordant findings on immunohistochemistry and MSI testing, 6 were explained by false positive screening results and 2 were found to have two somatic tumor mutations. This underscores the importance of repeating immunohistochemistry and MSI testing in cases with discordant screening results to rule out false positive tests. In the 2 discordant cases with somatic mutations, the tumor was either MSI-low or MSS and immunohistochemistry had absent MSH6 with somatic mutations found in MSH6. MSH6 is known to be associated with MSS or MSI-low status more often than the other three MMR genes.

We attempted to determine the mutation burden in the tumors as a higher mutation burden is known to occur in MSI tumors as compared to microsatellite stable tumors. Our study shows that tumors with pathogenic somatic MMR mutations displayed a hypermutated phenotype which supports the hypothesis that these somatic MMR mutations result in loss of DNA mismatch repair pathway function. The frequency of mutations was highest if they co-existed with mutations in the DNA polymerase POLE. POLE mutations were first implicated as a potential cause of MSI in colorectal cancer cell lines without identifiable MMR mutations29 and were recently found in the germline of patients with a history of multiple adenomas; colorectal tumors from these patients were microsatellite stable and hypermutated.30 In the Cancer Genome Atlas Project, a certain subset of hypermutated colon cancers had POLE aberrations that co-existed with mutations in the MMR genes but these tumors tended to be microsatellite stable.5 Our study shows that MMR mutations and POLE mutations can co-exist and cause MSI and a hyper/ultramutated phenotype, but it is not clear whether POLE mutations are the initiating event which subsequently causes MMR gene mutations or vice versa. This deserves further study.

Patients with tumors deficient in mismatch repair protein without somatic hypermethylation or MMR germline mutations have been referred to as having Lynch-like syndrome and have attracted considerable attention in the last year.10,23,31 Recent publications including this study suggest that many of these can be explained by two somatic tumor mutations.12,13 It is not clear why tumors develop via this pathway and whether they present at a similar age and have a similar course as other cancers with deficient MMR systems. Mesenkamp et al. showed that the age at diagnosis of patients with two somatic MMR mutated tumors was not significantly higher than that of Lynch syndrome-associated tumors, while MLH1 promoter methylated tumors were diagnosed at a significantly higher age.13 In the Spanish EPICOLON study, the mean age of onset for colorectal cancer was similar in Lynch syndrome patients (48.5 +/−14.1 years) and Lynch-like syndrome patients (53.7+/−16.8 years).10 Our study also suggests that patients with two somatic MMR mutations may be younger, with a median age of 57.0 years at diagnosis, but as we were not able to test every unexplained case, selection bias may have affected the median age. The ongoing OCCPI study will shed further light on this as we plan on testing all unexplained cases with abnormal screening for somatic tumor mutations. Only 9% of patients with somatic MMR mutated tumors fulfilled Amsterdam criteria and 27% fulfilled Bethesda criteria.

In conclusion, we believe that tumor DNA sequencing should be undertaken in unsolved cases of abnormal Lynch syndrome screening without identifiable germline mutations as it can explain two-thirds of these cases and help guide genetic counseling and reduce patient anxiety. Most of the remaining unexplained cases had false positive screening tests so it is important to repeat screening tests to confirm prior results especially in cases where the MSI and immunohistochemical results are discordant. It is important to establish a method to resolve these cases in the setting of increased implementation of universal screening for Lynch syndrome. Based on this study, it appears that intensive cancer screening surveillance would be unnecessary in 69% of cases with abnormal screening without an identifiable germline mutation as they can be explained by somatic mutations. Assuming the most likely scenario that the somatic mutations developed in the tumor and there is not somatic mosaicism for a MMR gene mutation, these patients and their at-risk relatives can be clinically followed the same way as anyone with a personal or family history of colorectal cancer. Future research should address the mechanisms and clinical implications of endometrial and colorectal cancer patients who acquire somatic mutations in MMR genes and develop tumors via the hypermutated pathway rather than the chromosomal instability pathway.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Grant Support: This study was supported by grants from Pelotonia and the National Cancer Institute (CA16058 and CA67941). We thank Christina Smith, Karen Koehler, Mallory Beightol, Shelby Flowers, and Tatyana Marushchak for performing genomic library preparation and sequencing, Angela Jacobson and Dr. Robert Livingston for help with research coordination, Dr. Brian Shirts and Dr. Tom Walsh for assistance with variant interpretation, and Dr. Stephen Salipante, Dr. Emily Turner, and Sheena Scroggins for help with bioinformatics. We would also like to thank Dr. C. Richard Boland and Dr. Jennifer Rhees at Baylor University Medical Center for generously sharing a positive control for the MSH2 inversion with us.

Ms. Heather Hampel has received research funding from Myriad Genetic Laboratories.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures

Other authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Author Contributions

Ms. Hampel and Dr. de la Chapelle were responsible for developing the study concept and the design of both clinical trials from which patient samples were obtained. Dr. Pritchard coordinated the next-generation sequencing and performed data analysis and Dr. Haraldsdottir and Dr. Tomsic performed the Sanger sequencing. Clinical data were collected and analyzed by Dr. Haraldsdottir and Ms. Pearlman. Dr. Frankel performed immunohistochemistry analysis. Dr. Haraldsdottir was responsible for the primary manuscript draft and all authors contributed to the critical revision of the manuscript. Dr. de la Chapelle, Dr. Pritchard, and Ms. Hampel obtained funding for the study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hampel H, Frankel WL, Martin E, et al. Screening for the Lynch Syndrome (Hereditary Nonpolyposis Colorectal Cancer) New England Journal of Medicine. 2005;352(18):1851–1860. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hampel H, Frankel WL, Martin E, et al. Feasibility of Screening for Lynch Syndrome Among Patients With Colorectal Cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2008 2008 Dec 10;26(35):5783–5788. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.5950. 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hampel H, Frankel W, Panescu J, et al. Screening for Lynch Syndrome (Hereditary Nonpolyposis Colorectal Cancer) among Endometrial Cancer Patients. Cancer Research. 2006 Aug 1;66(15):7810–7817. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1114. 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hampel H, Panescu J, Lockman J, et al. Comment on: Screening for Lynch Syndrome (Hereditary Nonpolyposis Colorectal Cancer) among Endometrial Cancer Patients. Cancer Research. 2007 Oct 1;67(19):9603. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2308. 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Comprehensive molecular characterization of human colon and rectal cancer. Nature. 2012;487(7407):330–337. doi: 10.1038/nature11252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Recommendations from the EGAPP Working Group: genetic testing strategies in newly diagnosed individuals with colorectal cancer aimed at reducing morbidity and mortality from Lynch syndrome in relatives. Genet Med. 2009;11(1):35–41. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e31818fa2ff. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beamer LC, Grant ML, Espenschied CR, et al. Reflex Immunohistochemistry and Microsatellite Instability Testing of Colorectal Tumors for Lynch Syndrome Among US Cancer Programs and Follow-Up of Abnormal Results. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2012 Apr 1;30(10):1058–1063. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.4719. 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ligtenberg MJL, Kuiper RP, Chan TL, et al. Heritable somatic methylation and inactivation of MSH2 in families with Lynch syndrome due to deletion of the 3[prime] exons of TACSTD1. Nat Genet. 2009;41(1):112–117. doi: 10.1038/ng.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rhees J, Arnold M, Boland CR. Inversion of exons 1–7 of the MSH2 gene is a frequent cause of unexplained Lynch syndrome in one local population. Familial Cancer. 2013 Oct 11;:1–7. doi: 10.1007/s10689-013-9688-x. 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rodríguez–Soler M, Pérez–Carbonell L, Guarinos C, et al. Risk of Cancer in Cases of Suspected Lynch Syndrome Without Germline Mutation. Gastroenterology. 2013;144(5):926–932. e921. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.01.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weissman S, Burt R, Church J, et al. Identification of Individuals at Risk for Lynch Syndrome Using Targeted Evaluations and Genetic Testing: National Society of Genetic Counselors and the Collaborative Group of the Americas on Inherited Colorectal Cancer Joint Practice Guideline. J Genet Counsel. 2012 Aug 01;21(4):484–493. doi: 10.1007/s10897-011-9465-7. 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sourrouille I, Coulet F, Lefevre J, et al. Somatic mosaicism and double somatic hits can lead to MSI colorectal tumors. Familial Cancer. 2013 Mar 01;12(1):27–33. doi: 10.1007/s10689-012-9568-9. 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mensenkamp AR, Vogelaar IP, van Zelst–Stams WAG, et al. Somatic Mutations in MLH1 and MSH2 Are a Frequent Cause of Mismatch-Repair Deficiency in Lynch Syndrome-Like Tumors. Gastroenterology. 2014;146(3):643–646. e648. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. ClinicalTrials.gov. Ohio Colorectal Cancer Prevention Initiative (OCCPI) [Accessed 04/10/2014]; http://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT01850654.

- 15.Pritchard CC, Smith C, Salipante SJ, et al. ColoSeq provides comprehensive lynch and polyposis syndrome mutational analysis using massively parallel sequencing. J Mol Diagn. 2012 Jul;14(4):357–366. doi: 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2012.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pritchard CC, Smith C, Marushchak T, et al. A mosaic PTEN mutation causing Cowden syndrome identified by deep sequencing. Genet Med. 2013;15(12):1004–1007. doi: 10.1038/gim.2013.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koboldt DC, Zhang Q, Larson DE, et al. VarScan 2: Somatic mutation and copy number alteration discovery in cancer by exome sequencing. Genome Research. 2012 Mar 1;22(3):568–576. doi: 10.1101/gr.129684.111. 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li J, Lupat R, Amarasinghe KC, et al. CONTRA: copy number analysis for targeted resequencing. Bioinformatics. 2012 May 15;28(10):1307–1313. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts146. 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ye K, Schulz MH, Long Q, Apweiler R, Ning Z. Pindel: a pattern growth approach to detect break points of large deletions and medium sized insertions from paired-end short reads. Bioinformatics. 2009 Nov 1;25(21):2865–2871. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp394. 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pritchard CC, Salipante SJ, Koehler K, et al. Validation and Implementation of Targeted Capture and Sequencing for the Detection of Actionable Mutation, Copy Number Variation, and Gene Rearrangement in Clinical Cancer Specimens. The Journal of Molecular Diagnostics. 2014;16(1):56–67. doi: 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2013.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Salipante SJ, Scroggins SM, Hampel HL, Turner EH, Pritchard CC. Microsatellite Instability Detection by Next Generation Sequencing. Clinical Chemistry. 2014 Jun 30; doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2014.223677. 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thompson BA, Spurdle AB, Plazzer J-P, et al. Application of a 5-tiered scheme for standardized classification of 2,360 unique mismatch repair gene variants in the InSiGHT locus-specific database. Nat Genet. 2014;46(2):107–115. doi: 10.1038/ng.2854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carethers JM. Differentiating Lynch-Like From Lynch Syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2014;146(3):602–604. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.01.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang J, Lindroos A, Ollila S, et al. Gene Conversion Is a Frequent Mechanism of Inactivation of the Wild-Type Allele in Cancers from MLH1/MSH2 Deletion Carriers. Cancer Research. 2006 Jan 15;66(2):659–664. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4043. 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ollikainen M, Hannelius U, Lindgren CM, Abdel-Rahman WM, Kere J, Peltomaki P. Mechanisms of inactivation of MLH1 in hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal carcinoma: a novel approach. Oncogene. 2007;26(31):4541–4549. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang R, Qin W, Xu GL, Zeng FF, Li CX. A meta-analysis of the prevalence of somatic mutations in the hMLH1 and hMSH2 genes in colorectal cancer. Colorectal Disease. 2012;14(3):e80–e89. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2011.02858.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hemminki A, Peltomaki P, Mecklin J-P, et al. Loss of the wild type MLH1 gene is a feature of hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer. Nat Genet. 1994;8(4):405–410. doi: 10.1038/ng1294-405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Desai DC, Lockman JC, Chadwick RB, et al. Recurrent germline mutation in MSH2arises frequently de novo. Journal of Medical Genetics. 2000 Sep 1;37(9):646–652. doi: 10.1136/jmg.37.9.646. 2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.da Costa LT, Liu B, El-Deiry WS, et al. Polymerase [delta] variants in RER colorectal tumours. Nat Genet. 1995;9(1):10–11. doi: 10.1038/ng0195-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Palles C, Cazier J-B, Howarth KM, et al. Germline mutations affecting the proofreading domains of POLE and POLD1 predispose to colorectal adenomas and carcinomas. Nat Genet. 2013;45(2):136–144. doi: 10.1038/ng.2503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boland CR. The Mystery of Mismatch Repair Deficiency: Lynch or Lynch-like? Gastroenterology. 2013;144(5):868–870. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.