Abstract

Background

Many clinical trials use composite endpoints to reduce sample size, but the relative importance of each individual endpoint within the composite may differ between patients and researchers.

Methods and Results

We asked 785 cardiovascular patients and 164 clinical trial authors to assign 25 “spending weights” across 5 common adverse events comprising composite endpoints in cardiovascular trials: death, myocardial infarction (MI), stroke, coronary revascularization, and hospitalization for angina. We then calculated endpoint ratios (“ratios”) for each participant’s ratings of each nonfatal endpoint relative to death. Whereas patients assigned an average weight of 5 to death, equal or greater weight was assigned to MI (mean ratio 1.12) and stroke (ratio 1.08). In contrast, clinical trialists were much more concerned about death (average weight of 8) than MI (ratio 0.63) or stroke (ratio 0.53). Both patients and trialists considered revascularization (ratios 0.48 and 0.20, respectively) and hospitalization (ratios 0.28 and 0.13, respectively) as substantially less severe than death. Differences between patient and trialist endpoint weights persisted after adjustment for demographic and clinical characteristics (p<0.001 for all comparisons).

Conclusions

Neither patients nor clinical trialists weigh individual components of a composite endpoint equally. While trialists are most concerned about avoiding death, patients place equal or greater importance on reducing MI or stroke. Both groups considered revascularization and hospitalization as substantially less severe. These findings suggest that equal weights in a composite clinical endpoint do not accurately reflect the preferences of either patients or trialists.

Keywords: clinical trial, statistics, cardiovascular disease, patient-centered care

Clinical trials frequently use a composite primary endpoint to increase event rates, improve trial efficiency, and decrease study costs.1–3 However, analytic approaches to composite endpoints typically assume that the individual components are of similar importance. In practice, a treatment often has different effects on each individual endpoint, resulting in uncertainty when interpreting the results of a clinical trial employing a composite primary endpoint.4–7

Some investigators have recommended using a weighted composite endpoint to address these concerns, in which individual components are valued relative to one another.4, 5, 7, 8 However, data to inform the weighting of individual endpoints, using opinions from both clinical trial authors and patients, has not been collected. Furthermore, prior efforts to weigh composite endpoints have assumed that patients, physicians, and clinical trialists would assign similar values to individual events (e.g., severity of stroke relative to death). If patients value individual components of a composite endpoint differently from trialists, this would suggest that efforts to develop weighted composite endpoints may also need to address patient preferences.

Accordingly, we asked both patients and clinical trialists to weigh the relative importance of frequently measured outcomes from cardiovascular clinical trials. To better understand the value of each endpoint for patients and trialists, we quantified the relative severity of each endpoint when compared to death and assessed for rating differences between the two groups. In addition, we examined whether endpoint weights varied by the demographic and clinical characteristics of patients and trialists.

Methods

Selection of Patients

We administered a voluntary survey to patients managed by a single-specialty cardiovascular practice at an academic medical center (Saint Luke’s Mid America Heart Institute, Kansas City, MO). Potential subjects were approached at random in the office waiting or procedural holding areas, at varying times of day, over a 3-month recruiting period. After obtaining verbal consent, subjects anonymously completed the survey described below. The survey was personally administered by a member of the research team, and explanations regarding the assignment of endpoint weights (i.e., sum of 25 points) were provided as needed.

Selection of Trialists

In parallel with the patient survey, an identical electronic survey was administered to authors of major randomized clinical trials of statin lipid-lowering drugs and coronary revascularization therapies published in the English-speaking literature between 2000 and 2009. Potential clinical trials were identified through Medline searches, literature review, and the clinicaltrials.gov website (see eTables 1 and 2). Only investigators from trials with clinical endpoints were included in this survey; trials with surrogate marker endpoints (e.g., lipid levels, ultrasound or computed tomography findings, angiographic late loss after coronary intervention) were not included. E-mail addresses were collected from Medline and Internet browser searches by the study investigators and stored in a secure database, after which an invitation was sent via e-mail with links to participate or decline participation. Each clinical trialist was only permitted to complete the survey once, even if listed as an author on multiple clinical trials.

Survey Data Collection

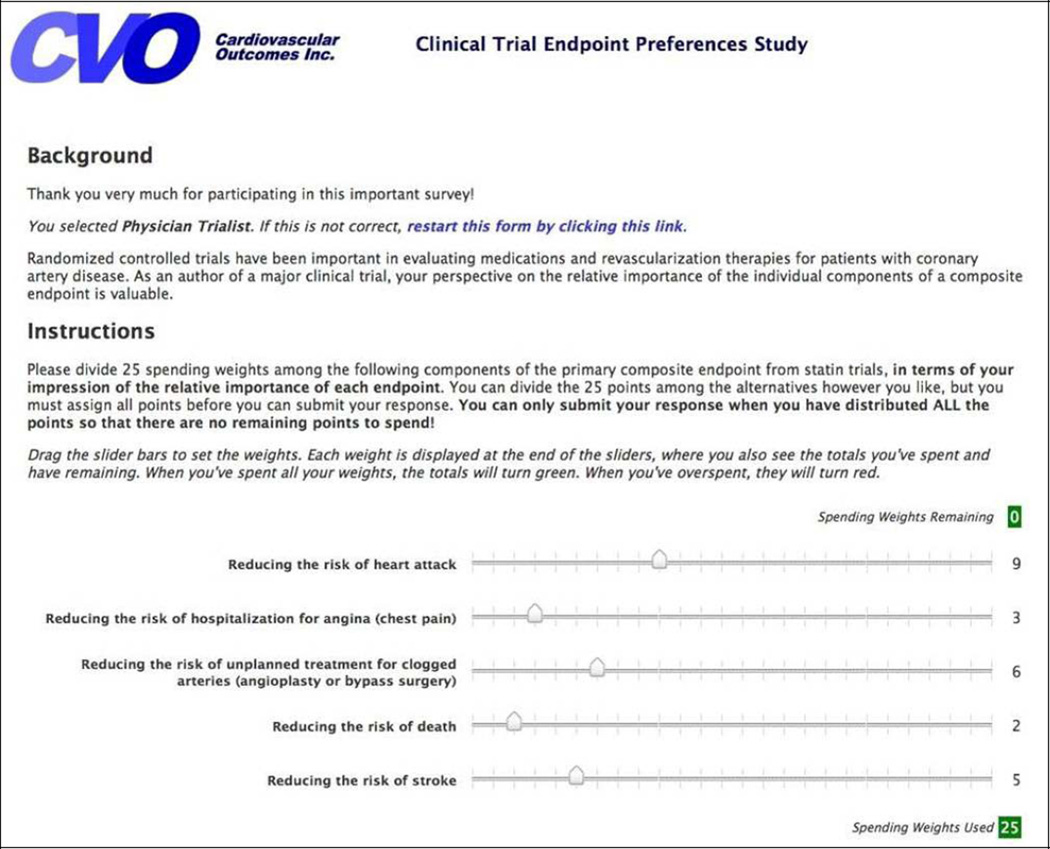

The text of the survey is illustrated in Figure 1. Although demographic and clinical data collected were specific to patients and trialists, the same survey for weighing clinical outcomes was administered to both groups. Each respondent was asked to distribute 25 “spending weights” among five clinical outcomes commonly included in composite primary endpoints of clinical trials of statins and coronary revascularization: death, myocardial infarction (MI), stroke, coronary revascularization, and hospitalization for angina. All respondents were required to distribute exactly 25 weights across the five endpoints, and verification of the 25-point total was ensured before the survey could be submitted. To minimize bias, the specific order of the 5 individual endpoints to be weighed was varied at random for both patients and trialists.

Figure 1. Survey for Weighing Clinical Endpoints.

The order of individual endpoints was varied at random to help minimize bias when assigning endpoint weights.

Analytic Approach

To facilitate interpretation as percentages, we rescaled the data so that the weights sum to 100. We then converted each respondent’s endpoint weights to ratios, by dividing the weight assigned to each non-fatal endpoint (MI, stroke, revascularization, and hospitalization) by the weight assigned to mortality. These ratios represent the relative unadjusted weights assigned to each of the 4 non-fatal endpoints versus the reference of death. For example, a respondent who assigned values of 10, 5, 5, 3, and 2 points for death, MI, stroke, revascularization, and hospitalization, respectively, would have endpoint ratios of 0.5, 0.5, 0.3, and 0.2 for MI, stroke, revascularization, and hospitalization relative to death.

We then assessed whether the weights assigned by trialists differed from those of patients. Because the weights represent a special type of multivariate data known as compositional data, which are constrained to add up to a constant value (i.e., 25 points),9 we used multivariate methods appropriate to multiple correlated dependent variables. This constant-sum constraint imposes a mathematical structure to the data (an increase in one variable mathematically necessitates a decrease in another) for which standard statistical methods are not appropriate. To accomplish this, the four endpoint ratios for each participant were log-transformed and analyzed using standard repeated measures analysis of variance models. This model included a fixed effect for respondent type (patient or trialist), a respondent type-by-endpoint interaction term, and an unstructured residual covariance matrix to account for differing variances and within-respondent correlations among the four variables.

Next, we conducted analyses to examine the association between respondent characteristics and endpoint weights, separately for patients and trialists. Continuous characteristics (e.g., age) were categorized so that predicted mean weights could be displayed for each category. We first analyzed each respondent characteristic individually in unadjusted models, similar to that described above. Next, we fit a multivariable model including all respondent characteristics, and performed backward selection (p<0.05) to retain only those characteristics that were associated with endpoint weights.

For responses in which a specific endpoint was assigned a weight of zero (e.g., 0 points assigned to revascularization by an individual patient or trialist), we replaced the zero with a uniform random positive fractional weight <0.5 to avoid mathematical difficulties in calculating log ratios. This assumes that a reported weight of zero was a “detection limit” error due to the coarseness of the response scale (0–25); i.e., that respondents would have given at least some nominal positive weight to the endpoint if a large enough number of spending points were available. To account for the uncertainty in these replaced values, we used multiple imputation methods. Specifically, we repeated the zero-replacement process 25 times, generating 25 distinct complete data sets. All analyses described above were replicated on each of the 25 data sets, and the results from each were pooled to obtain final estimates for statistical inferences. This approach allows calculation of endpoint log ratios for all respondents and appropriately incorporates uncertainty due to imputation.

All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, North Carolina) and R version 2.10.0 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). For each analysis, we evaluated the null hypothesis at a 2-sided significance level of 0.05. Findings are reported as mean [interquartile range]. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Saint Luke’s Hospital.

Results

Comparison Between Patients and Trialists

A total of 785 patients and 164 clinical trialists completed the study survey, representing response rates of >95% of patients solicited and ~60% of trialists with valid e-mail addresses. Overall, there were marked differences (P<0.001) in how patients and clinical trialists weighed the relative severity of each endpoint compared with death (Table 1). In general, patients assigned slightly higher importance to MI and stroke as death (endpoint ratios of 1.12 and 1.08, respectively) and viewed repeat revascularization and hospitalization as significantly less severe than death (endpoint ratios 0.48 and 0.28, respectively). In contrast, clinical trialists assigned one-third and one-half as much importance to MI or stroke (endpoint ratios 0.63 and 0.53, respectively) than death, and they weighed repeat revascularization and hospitalization as relatively minor events (endpoint ratios 0.20 and 0.13, respectively).

Table 1.

Comparison of Endpoint Weights By Patients and Clinical Trial Authors

| Endpoint Weight | Endpoint Ratio vs. Death | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Death | MI | Stroke | Revasc | Hosp | MI | Stroke | Revasc | Hosp | P | |

| Respondent | <0.001* | ||||||||||

| Patients | 785 | 25 (12–40) | 28 (20–32) | 27 (16–32) | 12 (0–20) | 7 (0–20) | 1.12 | 1.08 | 0.48 | 0.28 | |

| Trialists | 164 | 40 (28–48) | 25 (18–28) | 21 (16–28) | 8 (4–12) | 5 (4–8) | 0.63 | 0.53 | 0.20 | 0.13 | |

Hosp indicates hospitalization for angina; MI, myocardial infarction; Revasc, coronary revascularization procedure.

Values are reported as mean (interquartile range) on a 100-point scale.

For comparison of the distribution of patient vs. trialist weights.

Patient Subgroups

Endpoint weights for patient subgroups are summarized in Table 2. Overall, 54% of patients were male, 84% were Caucasian, and more than half were 65 years of age or older. Nearly 60% had a college or graduate degree, 55% were retired, and two-thirds were currently married. More than two-thirds of patients had hypertension or hypercholesterolemia, 1 in 4 had a prior MI, 1 in 3 had undergone prior percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), and 1 in 6 had undergone prior coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG).

Table 2.

Patient Endpoint Weights and Ratios According to Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

| Mean Endpoint Weights* | Relative Weight vs. Death | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | N (%)* | Death | MI | Stroke | Revasc | Hosp | MI | Stroke | Revasc | Hosp | P** |

| Age (yrs) | <0.001 | ||||||||||

| 18–44 | 82 (10%) | 41 | 21 | 17 | 13 | 7 | 0.51 | 0.41 | 0.32 | 0.17 | |

| 45–54 | 101 (13%) | 29 | 29 | 24 | 11 | 8 | 1.00 | 0.83 | 0.38 | 0.28 | |

| 55–64 | 167 (21%) | 28 | 28 | 24 | 13 | 7 | 1.00 | 0.86 | 0.46 | 0.25 | |

| 65–74 | 217 (28%) | 23 | 29 | 29 | 12 | 7 | 1.26 | 1.26 | 0.52 | 0.30 | |

| 75–84 | 178 (23%) | 21 | 30 | 31 | 11 | 8 | 1.43 | 1.48 | 0.52 | 0.38 | |

| 85+ | 39 (5%) | 11 | 27 | 40 | 12 | 9 | 2.45 | 3.64 | 1.09 | 0.82 | |

| Sex | 0.43 | ||||||||||

| Male | 419 (54%) | 24 | 30 | 26 | 12 | 8 | 1.25 | 1.08 | 0.50 | 0.33 | |

| Female | 364 (46%) | 26 | 27 | 28 | 12 | 7 | 1.04 | 1.08 | 0.46 | 0.27 | |

| Race | 0.010 | ||||||||||

| Caucasian | 655 (84%) | 25 | 28 | 28 | 12 | 7 | 1.12 | 1.12 | 0.48 | 0.28 | |

| African-American | 101 (13%) | 25 | 33 | 20 | 11 | 11 | 1.32 | 0.80 | 0.44 | 0.44 | |

| Other | 26 (3%) | 21 | 29 | 28 | 14 | 8 | 1.38 | 1.33 | 0.67 | 0.38 | |

| Annual income | 0.001 | ||||||||||

| $0 – 40K | 345 (48%) | 23 | 28 | 27 | 14 | 9 | 1.22 | 1.17 | 0.61 | 0.39 | |

| $40 – 80K | 194 (27%) | 25 | 29 | 28 | 11 | 7 | 1.16 | 1.12 | 0.44 | 0.28 | |

| $80 – 120K | 86 (12%) | 27 | 26 | 30 | 10 | 6 | 0.96 | 1.11 | 0.37 | 0.22 | |

| > $120K | 95 (13%) | 34 | 31 | 22 | 9 | 5 | 0.91 | 0.65 | 0.26 | 0.15 | |

| Education | 0.57 | ||||||||||

| ≤ High school | 324 (41%) | 23 | 30 | 26 | 13 | 9 | 1.30 | 1.13 | 0.57 | 0.39 | |

| College | 300 (39%) | 27 | 27 | 27 | 12 | 7 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.44 | 0.26 | |

| Graduate school | 156 (20%) | 27 | 28 | 27 | 11 | 7 | 1.04 | 1.00 | 0.41 | 0.26 | |

| Employment | 0.10 | ||||||||||

| Full time | 218 (28%) | 29 | 29 | 24 | 12 | 6 | 1.00 | 0.83 | 0.41 | 0.21 | |

| Part time | 59 (8%) | 34 | 22 | 22 | 14 | 7 | 0.65 | 0.65 | 0.41 | 0.21 | |

| Retired | 428 (55%) | 22 | 30 | 29 | 11 | 8 | 1.36 | 1.32 | 0.50 | 0.36 | |

| Unemployed | 74 (9%) | 25 | 26 | 26 | 12 | 11 | 1.04 | 1.04 | 0.48 | 0.44 | |

| Marital status | 0.14 | ||||||||||

| Married | 514 (66%) | 27 | 29 | 26 | 11 | 7 | 1.07 | 0.96 | 0.41 | 0.26 | |

| Never | 74 (9%) | 35 | 23 | 22 | 11 | 8 | 0.66 | 0.63 | 0.31 | 0.23 | |

| Previously married | 96 (12%) | 20 | 30 | 27 | 14 | 8 | 1.50 | 1.35 | 0.70 | 0.40 | |

| Widowed | 98 (13%) | 17 | 28 | 35 | 12 | 8 | 1.65 | 2.06 | 0.71 | 0.47 | |

| Hypertension | 0.10 | ||||||||||

| Yes | 545 (70%) | 23 | 29 | 28 | 12 | 8 | 1.26 | 1.22 | 0.52 | 0.35 | |

| No | 236 (30%) | 31 | 27 | 25 | 11 | 6 | 0.87 | 0.81 | 0.35 | 0.19 | |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 0.18 | ||||||||||

| Yes | 524 (67%) | 24 | 29 | 27 | 13 | 7 | 1.21 | 1.13 | 0.54 | 0.29 | |

| No | 257 (33%) | 28 | 28 | 26 | 10 | 8 | 1.00 | 0.93 | 0.36 | 0.29 | |

| Diabetes | 0.23 | ||||||||||

| Yes | 182 (23%) | 25 | 32 | 24 | 11 | 8 | 1.28 | 0.96 | 0.44 | 0.32 | |

| No | 599 (77%) | 25 | 28 | 28 | 12 | 7 | 1.12 | 1.12 | 0.48 | 0.28 | |

| Prior MI | 0.47 | ||||||||||

| Yes | 195 (25%) | 24 | 30 | 24 | 13 | 8 | 1.20 | 1.00 | 0.54 | 0.33 | |

| No | 586 (75%) | 25 | 28 | 28 | 12 | 7 | 1.12 | 1.12 | 0.48 | 0.28 | |

| Prior PCI | 0.07 | ||||||||||

| Yes | 261 (33%) | 22 | 29 | 26 | 15 | 8 | 1.32 | 1.18 | 0.68 | 0.36 | |

| No | 520 (67%) | 27 | 28 | 27 | 11 | 7 | 1.04 | 1.00 | 0.41 | 0.26 | |

| Prior CABG | 0.15 | ||||||||||

| Yes | 139 (18%) | 19 | 29 | 29 | 14 | 9 | 1.53 | 1.53 | 0.74 | 0.47 | |

| No | 642 (82%) | 27 | 28 | 26 | 12 | 7 | 1.04 | 0.96 | 0.44 | 0.26 | |

| Chronic heart failure | 0.40 | ||||||||||

| Yes | 182 (23%) | 28 | 26 | 27 | 11 | 8 | 0.93 | 0.96 | 0.39 | 0.29 | |

| No | 597 (77%) | 24 | 29 | 27 | 12 | 7 | 1.21 | 1.13 | 0.50 | 0.29 | |

| Prior stroke | 0.90 | ||||||||||

| Yes | 88 (11%) | 23 | 27 | 28 | 14 | 8 | 1.17 | 1.22 | 0.61 | 0.35 | |

| No | 692 (89%) | 25 | 29 | 27 | 12 | 7 | 1.16 | 1.08 | 0.48 | 0.28 | |

| Angina | 0.36 | ||||||||||

| Current | 115 (15%) | 23 | 29 | 26 | 12 | 10 | 1.26 | 1.13 | 0.52 | 0.43 | |

| Past | 200 (26%) | 26 | 26 | 26 | 14 | 8 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.54 | 0.31 | |

| Never | 465 (59%) | 25 | 29 | 27 | 11 | 7 | 1.16 | 1.08 | 0.44 | 0.28 | |

| Defibrillator | 0.73 | ||||||||||

| Yes | 89 (11%) | 26 | 27 | 30 | 10 | 7 | 1.04 | 1.15 | 0.38 | 0.27 | |

| No | 692 (89%) | 25 | 29 | 26 | 12 | 8 | 1.16 | 1.04 | 0.48 | 0.32 | |

| Atrial fibrillation | 0.07 | ||||||||||

| Yes | 278 (36%) | 25 | 27 | 31 | 11 | 7 | 1.08 | 1.24 | 0.44 | 0.28 | |

| No | 497 (64%) | 25 | 30 | 25 | 13 | 8 | 1.20 | 1.00 | 0.52 | 0.32 | |

| Smoking status | 0.24 | ||||||||||

| Current | 86 (11%) | 24 | 25 | 27 | 14 | 10 | 1.04 | 1.13 | 0.58 | 0.42 | |

| Former | 353 (45%) | 24 | 31 | 27 | 11 | 8 | 1.29 | 1.13 | 0.46 | 0.33 | |

| Never | 342 (44%) | 27 | 27 | 27 | 12 | 7 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.44 | 0.26 | |

| Alcohol use | 0.42 | ||||||||||

| Frequent | 55 (7%) | 24 | 26 | 29 | 11 | 10 | 1.08 | 1.21 | 0.46 | 0.42 | |

| Occasional | 403 (52%) | 26 | 28 | 26 | 12 | 7 | 1.08 | 1.00 | 0.46 | 0.27 | |

| Quit | 132 (17%) | 23 | 31 | 26 | 11 | 10 | 1.35 | 1.13 | 0.48 | 0.43 | |

| Never | 190 (24%) | 24 | 28 | 28 | 12 | 7 | 1.17 | 1.17 | 0.50 | 0.29 | |

CABG indicates coronary artery bypass surgery; Hosp, hospitalization for angina; MI, myocardial infarction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; Revasc, coronary revascularization procedure.

Mean endpoint weights may not add exactly to 100 due to rounding, and total N in each subgroup may not add to 785 patients due to differential response rates for each question.

P-value for comparison of endpoint weights across categories of each characteristic.

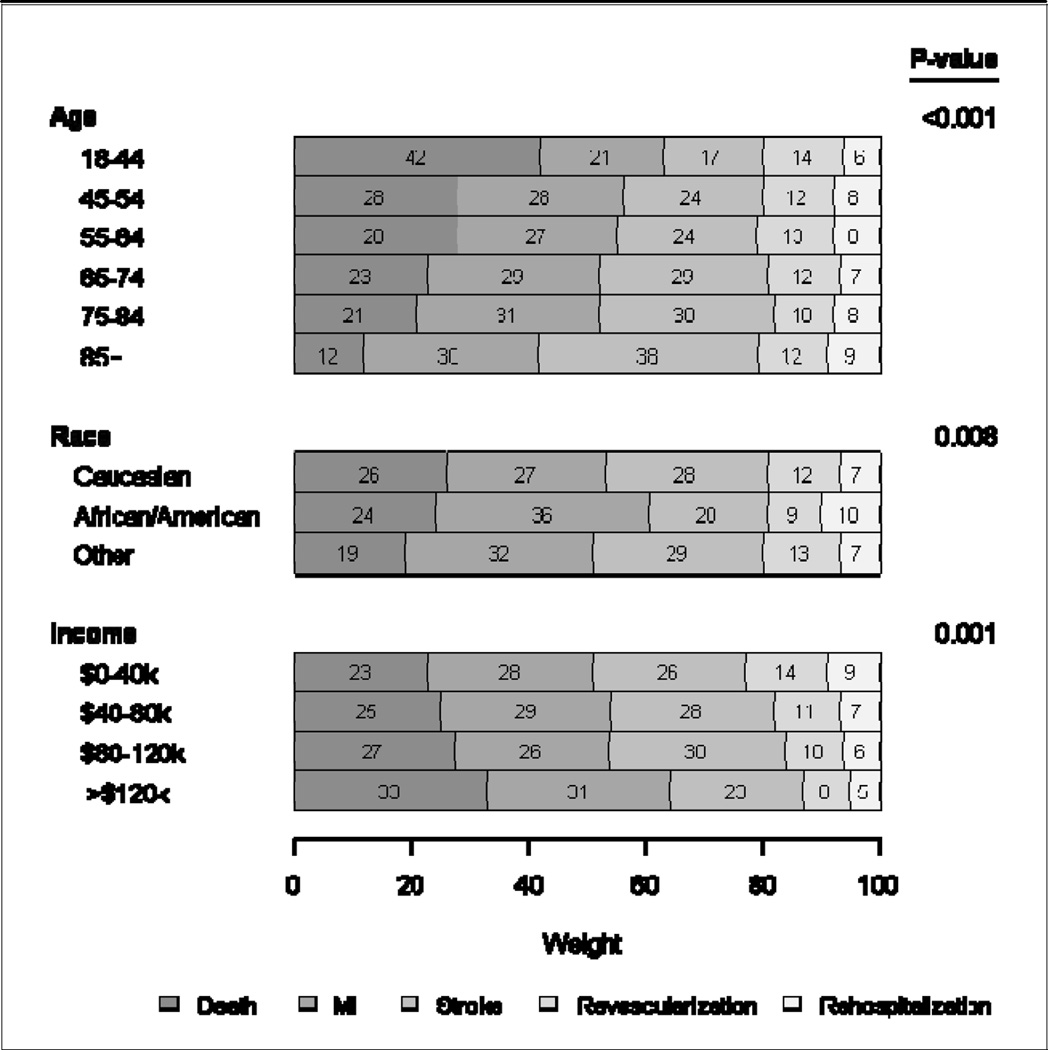

Although patients, in aggregate, assigned weights of relatively similar importance for MI and stroke compared with death, there were differences by age, race, and household income level. Patients under 45 years of age weighed death as twice as severe as MI or stroke, whereas older patients (65–74, 75–84, and ≥85) assigned greater importance to avoiding MI or stroke than death (P<0.001 across age categories) (see Table 2). Patients between 45 and 64 viewed death, MI, and stroke as equally severe. African-American patients were more concerned about MI than either stroke or death, whereas Caucasian patients were equally concerned about death, stroke, and MI (P=0.01 for comparison between races). Patients with household incomes less than $40,000 annually were more concerned about MI and stroke than death, whereas those with annual household incomes exceeding $120,000 were most concerned about death and assigned significantly less importance to revascularization (P=0.001). There were no differences in weighting assignments by other clinical and socioeconomic subgroups such as marital status, education level, employment status, or by medical comorbidity. These findings were similar in fully adjusted models (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Adjusted Endpoint Weights According to Patient Age, Race, and Annual Income.

Shaded bars indicate mean absolute weights (after rescaling data so that weights sum to 100), adjusted for all available demographic and clinical characteristics.

Clinical Trialist Subgroups

Endpoint weights for clinical trialist subgroups are displayed in Table 3. Among 164 clinical trialists, 93% were practicing in academic settings and 70% were 20 or more years out of training. One-half of the trialists were European, while another 39% were American. Nearly three-quarters were active investigators in patient enrollment for their respective clinical trials.

Table 3.

Endpoint Weights According to Demographic Characteristics of Clinical Trial Authors

| Endpoint Weight* | Relative Weight vs. Death | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | N (%)* | Death | MI | Stroke | Revasc | Hosp | MI | Stroke | Revasc | Hosp | P† |

| Percent clinical care | 0.005 | ||||||||||

| 0 to <20 | 27 (18%) | 32 | 31 | 26 | 6 | 5 | 0.97 | 0.81 | 0.19 | 0.16 | |

| 20 to <40 | 34 (23%) | 41 | 24 | 24 | 7 | 4 | 0.59 | 0.59 | 0.17 | 0.10 | |

| 40 to <60 | 32 (21%) | 44 | 21 | 20 | 8 | 6 | 0.48 | 0.45 | 0.18 | 0.14 | |

| 60 to <80 | 28 (19%) | 38 | 28 | 16 | 11 | 6 | 0.74 | 0.42 | 0.29 | 0.16 | |

| 80 to 100 | 29 (19%) | 45 | 23 | 17 | 9 | 6 | 0.51 | 0.38 | 0.20 | 0.13 | |

| Years post-training | 0.17 | ||||||||||

| 0 to <10 | 13 (9%) | 44 | 22 | 17 | 11 | 6 | 0.50 | 0.39 | 0.25 | 0.14 | |

| 10 to <20 | 31 (21%) | 45 | 22 | 19 | 9 | 6 | 0.49 | 0.42 | 0.20 | 0.13 | |

| 20 to <30 | 51 (34%) | 39 | 25 | 23 | 8 | 5 | 0.64 | 0.59 | 0.21 | 0.13 | |

| 30 to <40 | 45 (30%) | 37 | 28 | 21 | 8 | 7 | 0.76 | 0.57 | 0.22 | 0.19 | |

| 40 to 54 | 10 (7%) | 42 | 32 | 16 | 7 | 3 | 0.76 | 0.38 | 0.17 | 0.07 | |

| Practice type | 0.53 | ||||||||||

| Academic | 140 (93%) | 41 | 25 | 21 | 8 | 5 | 0.61 | 0.51 | 0.20 | 0.12 | |

| Private/industry | 10 (7%) | 33 | 26 | 20 | 14 | 7 | 0.79 | 0.61 | 0.42 | 0.21 | |

| Specialty‡ | 0.007 | ||||||||||

| General cardiology | 53 (35%) | 43 | 25 | 20 | 6 | 6 | 0.58 | 0.47 | 0.14 | 0.14 | |

| Interventional cardiology | 47 (31%) | 45 | 24 | 18 | 9 | 5 | 0.53 | 0.40 | 0.20 | 0.11 | |

| Invasive cardiology | 18 (12%) | 41 | 20 | 19 | 13 | 7 | 0.49 | 0.46 | 0.32 | 0.17 | |

| Preventative cardiology | 19 (13%) | 28 | 32 | 26 | 8 | 6 | 1.14 | 0.93 | 0.29 | 0.21 | |

| Other | 13 (9%) | 31 | 29 | 29 | 8 | 3 | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.26 | 0.10 | |

| Region | 0.34 | ||||||||||

| US | 64 (39%) | 39 | 26 | 22 | 7 | 6 | 0.67 | 0.56 | 0.18 | 0.15 | |

| Europe | 84 (51%) | 40 | 26 | 21 | 9 | 5 | 0.65 | 0.53 | 0.23 | 0.13 | |

| Other | 16 (10%) | 48 | 22 | 16 | 7 | 7 | 0.46 | 0.33 | 0.15 | 0.15 | |

| Trial role | 0.85 | ||||||||||

| Investigator | 118 (72%) | 41 | 25 | 21 | 8 | 5 | 0.61 | 0.51 | 0.20 | 0.12 | |

| Expert | 24 (15%) | 44 | 22 | 23 | 7 | 5 | 0.50 | 0.52 | 0.16 | 0.11 | |

| Other | 22 (13%) | 36 | 30 | 18 | 10 | 6 | 0.83 | 0.50 | 0.28 | 0.17 | |

Hosp indicates hospitalization for angina; MI, myocardial infarction; Revasc, coronary revascularization procedure

Mean endpoint weights may not add exactly to 100 due to rounding, and total N in each subgroup may not add to 164 trialists due to differential response rates for each question.

P-value for comparison of endpoint weights across categories of each characteristic.

Trialist specialty was self-designated by each respondent. Invasive cardiologists are trained in general cardiology and also are qualified to perform cardiac catheterization and diagnostic angiography. Interventional cardiologists are qualified to perform both the diagnostic procedures and a variety of more invasive measurements (e.g., intracoronary pressure or ultrasound assessments) and percutaneous therapies (e.g., coronary and peripheral arterial revascularization, valvuloplasty, repair of vascular and intracardiac defects).

In unadjusted analyses, clinical trialists who spent most of their time in clinical care were more likely to weigh death as more severe than stroke or MI (see Table 3). There were also differences by cardiovascular subspecialty in how trialists weighed the relative severity of death vs. MI and stroke. However, these differences were no longer significant after adjustment for physician characteristics (data not shown, all p>0.05), which suggests less variation in the weighing of clinical endpoints among trialists, when compared with variation in weighing among patients.

Discussion

Despite the common practice of weighing all adverse events equally within a clinical trial’s composite endpoint, we found that patients and clinical trial authors considered “hard” cardiovascular events (death, MI, stroke) significantly more important than repeat revascularization or hospitalization for angina. Moreover, among hard clinical endpoints, the relative value varied substantially between patients and trialists. Clinical trialists placed greater emphasis on avoiding death than MI or stroke, whereas patients viewed avoiding death, stroke, and MI as equally severe. Furthermore, there was heterogeneity in how patients weighed clinical endpoints according to age, race, and household income. Collectively, our findings provide important insights as to how clinical trialists and patients prioritize the goals of medical treatment.

For more than two decades, clinical trialists have struggled with the inadequacy of composite endpoints. Ideally, the components of the composite should have similar importance, frequency of occurrence, and response to the therapy being tested.4 However, these criteria are seldom met, and the clinical significance of individual endpoints within the composite can vary considerably.5 Not infrequently, trial results are driven by the impact of therapy on a single component outcome—often representing an event of much lesser severity (e.g., revascularization or rehospitalization) than hard endpoints such as death. For example, recurrent ischemia was primarily responsible for the reduction in the composite endpoints in one statin trial, whereas mortality was completely unaffected by randomization to statin therapy.10 Similarly, repeat revascularization drove the difference in the composite endpoint in multiple clinical trials comparing PCI versus CABG for multivessel coronary artery disease, with no differences in “hard” endpoints like mortality and myocardial infarction.11–13

To address these concerns, some authors have recommended a system of weighing composite endpoints. In 1989, Califf et al. surveyed 407 cardiologists at a national specialty conference to assign rank order to a list of endpoints,3 although this process did not quantify the relative severity of one endpoint relative to another. In 1992, Braunwald et al. assigned weights to death (1 point), disabling intracranial hemorrhage (1 point), heart failure (0.8 points), major bleeding (0.3 points), and other adverse events based on clinical importance or severity.14 The authors acknowledged the arbitrary nature of their weights and recommended continued refinement of these scores in the future.

Other studies have also attempted to provide relative values to different endpoints, either through arbitrary systems of assigning weights, by surveying clinical researchers to arrive at consensus weights,15–23 or through using disability-adjusted life-years to estimate endpoint importance to patients.24, 25 In addition, several studies have elicited patient and physician preferences regarding stroke prophylaxis in atrial fibrillation, or the threshold at which a patient would be willing to consider systemic anticoagulation to avoid suffering a stroke.27–29 One recent evaluation of patients used an online survey to confirm the lack of equal weighing in composite endpoints, and these authors recommended further emphasis on weighing individual adverse events to improve statistical validity and interpretation of clinical trial results.26 Our study expands these findings by evaluating weights by both clinical trialists and cardiovascular patients. To our knowledge, no other studies have solicited patient input on the relative severity of individual cardiovascular endpoints.

By surveying clinical trialists with the same clinical endpoints as the ones they used in their respective statin and coronary revascularization trials, we were able to generate relative weights for each individual endpoint compared with death. It is important to note that both the clinical trialists and patients apportioned different weights to death vs. stroke and MI. These differences were especially prominent among older patients, as stroke and MI were viewed as ~50% more important than death in those individuals 75 to 84 years of age, and 150% to 250% more important than death in those 85 years of age and older. Similarly, patients with low household income were more concerned about revascularization than those with higher household income, and thus placed at least as much importance on avoiding MI and stroke, if not more importance, than the avoidance of death. Of note, these observed differences in patients’ endpoint weights by age, race, and income persisted after adjustment for potential confounders such as education, marital and employment status, and other demographic and clinical variables. Differences between physicians and patients, and among patients themselves, suggest that development of weighted composite outcomes is complex and requires further study to help determine whether trialist, patient, or both patient and trialist preferences are needed in the development of endpoint weights for future clinical trials.

Study Limitations

The findings from our study should be interpreted in the context of several potential limitations. First, the patients included in this study’s survey were followed at a single-specialty cardiovascular practice, and results may not be generalizable to all patients. Second, the short period of time available for surveying patients waiting for office visits or procedures generally precluded a comprehensive discussion regarding the definitions of specific adverse events. For instance, the manifestations of myocardial infarction could range from minor elevations in myocardial enzymes to cardiogenic shock. As prior studies have not shown that patients rate MI as worse than death or similar to stroke, this difference could have occurred due to the brevity of our survey form and time of patient interaction. As a result, differences in baseline definitions of the endpoints between trialists and patients may have affected our comparisons of endpoint weights between the two groups. However, if such differences are present, they further reinforce the fact that these events have different significance between patients and trialists. Third, although our focus was to survey trialists since they are directly involved in clinical trial design, we did not survey physicians in daily clinical practice. Fourth, we focused our analyses on efficacy endpoints and did not assess the importance of safety endpoints, such as bleeding, as these are not typically included as part of a composite primary endpoint. Finally, although we derived weights for individual components of a composite endpoint, a systematic approach to weighing composite endpoints requires further study, especially given the differences identified between trialists and patients.

Conclusions

Although many contemporary clinical trials use composite endpoints to simplify and streamline the evaluation of new cardiovascular therapies, neither patients nor clinical trialists weight individual components of a composite endpoint equally. In addition, we found substantial differences between the preferences of patients and trialists regarding the relative importance of specific adverse events. These findings should stimulate further study into how best to develop composite endpoints that accurately reflect the severity of each individual endpoint component, and to address differences in how trialists and patients view their severity.

Acknowledgements

Dr. Stolker, Dr. Chan, and Mr. Jones had full access to the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. No independent funding was involved in the performance of this study.

Dr. Stolker reports receiving grant support from GE Healthcare; consulting for Cordis Corporation, and serving on the speaker’s bureau for Astra Zeneca, Astellas, and InfraReDx. Dr. Spertus reports receiving grants from the NHLBI of the National Institutes of Health, the American Heart Association, the American College of Cardiology Foundation, Lilly Pharmaceuticals, EvaHeart, Genentech, and Gilead Pharmaceuticals. He has served as a consultant to St. Jude Medical, United Healthcare, Amgen, Gilead, Genentech, and Janssen. He also owns several patents for quality-of-life questionnaires and is the President of Outcomes Instruments, LLC and CV Outcomes, Inc.; a 501(c)(3) corporation. Dr. Cohen reports obtaining research grants from Edwards Lifesciences, Medtronic, Abbott Vascular, Boston Scientific, Biomet, Eli Lilly, and Daiichi Sankyo. He has served as a consultant to Medtronic, Abbott Vascular, Eli Lilly, and Astra Zeneca.

Footnotes

Disclosures

All other authors (Jones, Jain, Bamberger, Lonergan, Chan) have no disclosures to report.

References

- 1.Freemantle N, Calvert M, Wood J, Eastaugh J, Griffin C. Composite outcomes in randomized trials: Greater precision but with greater uncertainty? JAMA. 2003;289:2554–2559. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.19.2554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cannon CP, Sharis PJ, Schweiger MJ, McCabe CH, Diver DJ, Shah PK, Sequeira RF, Greene RM, Perritt RL, Poole WK, Braunwald E. Prospective validation of a composite end point in thrombolytic trials of acute myocardial infarction (timi 4 and 5). Thrombosis in myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 1997;80:696–699. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(97)00497-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Califf RM, Harrelson-Woodlief L, Topol EJ. Left ventricular ejection fraction may not be useful as an end point of thrombolytic therapy comparative trials. Circulation. 1990;82:1847–1853. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.82.5.1847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaul S, Diamond GA. Trial and error. How to avoid commonly encountered limitations of published clinical trials. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:415–427. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.06.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kip KE, Hollabaugh K, Marroquin OC, Williams DO. The problem with composite end points in cardiovascular studies: The story of major adverse cardiac events and percutaneous coronary intervention. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51:701–707. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lauer MS, Topol EJ. Clinical trials--multiple treatments, multiple end points, and multiple lessons. JAMA. 2003;289:2575–2577. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.19.2575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tomlinson G, Detsky AS. Composite end points in randomized trials: There is no free lunch. JAMA. 2010;303:267–268. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Normand SL. Some old and some new statistical tools for outcomes research. Circulation. 2008;118:872–884. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.766907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Filzmoser p, hron k, reimann c. Univariate statistical analysis of environmental (compositional) data: Problems and possibilities. Sci Total Environ. 2009;407:6100–6108. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2009.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schwartz GG, Olsson AG, Ezekowitz MD, Ganz P, Oliver MF, Waters D, Zeiher A, Chaitman BR, Leslie S, Stern T. Effects of atorvastatin on early recurrent ischemic events in acute coronary syndromes: The miracl study: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2001;285:1711–1718. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.13.1711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Serruys PW, Unger F, Sousa JE, Jatene A, Bonnier HJ, Schonberger JP, Buller N, Bonser R, van den Brand MJ, van Herwerden LA, Morel MA, van Hout BA. Comparison of coronary-artery bypass surgery and stenting for the treatment of multivessel disease. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1117–1124. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200104123441502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Daemen J, Kuck KH, Macaya C, LeGrand V, Vrolix M, Carrie D, Sheiban I, Suttorp MJ, Vranckx P, Rademaker T, Goedhart D, Schuijer M, Wittebols K, Macours N, Stoll HP, Serruys PW. Multivessel coronary revascularization in patients with and without diabetes mellitus: 3-year follow-up of the arts-ii (arterial revascularization therapies study-part ii) trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:1957–1967. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Serruys PW, Morice MC, Kappetein AP, Colombo A, Holmes DR, Mack MJ, Stahle E, Feldman TE, van den Brand M, Bass EJ, Van Dyck N, Leadley K, Dawkins KD, Mohr FW. Percutaneous coronary intervention versus coronary-artery bypass grafting for severe coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:961–972. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0804626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Braunwald E, Cannon CP, McCabe CH. An approach to evaluating thrombolytic therapy in acute myocardial infarction. The 'unsatisfactory outcome' end point. Circulation. 1992;86:683–687. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.86.2.683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Allen LA, Hernandez AF, O'Connor CM, Felker GM. End points for clinical trials in acute heart failure syndromes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:2248–2258. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.12.079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Armstrong PW, Westerhout CM, Van de Werf F, Califf RM, Welsh RC, Wilcox RG, Bakal JA. Refining clinical trial composite outcomes: An application to the assessment of the safety and efficacy of a new thrombolytic-3 (assent-3) trial. Am Heart J. 2011;161:848–854. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2010.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brittain E, Palensky J, Blood J, Wittes J. Blinded subjective rankings as a method of assessing treatment effect: A large sample example from the systolic hypertension in the elderly program (shep) Stat Med. 1997;16:681–693. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19970330)16:6<681::aid-sim487>3.0.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Connolly SJ, Eikelboom JW, Ng J, Hirsh J, Yusuf S, Pogue J, de Caterina R, Hohnloser S, Hart RG. Net clinical benefit of adding clopidogrel to aspirin therapy in patients with atrial fibrillation for whom vitamin k antagonists are unsuitable. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:579–586. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-9-201111010-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Felker GM, Anstrom KJ, Rogers JG. A global ranking approach to end points in trials of mechanical circulatory support devices. J Card Fail. 2008;14:368–372. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2008.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ferreira-Gonzalez I, Busse JW, Heels-Ansdell D, Montori VM, Akl EA, Bryant DM, Alonso-Coello P, Alonso J, Worster A, Upadhye S, Jaeschke R, Schunemann HJ, Permanyer-Miralda G, Pacheco-Huergo V, Domingo-Salvany A, Wu P, Mills EJ, Guyatt GH. Problems with use of composite end points in cardiovascular trials: Systematic review of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2007;334:786. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39136.682083.AE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Follmann D, Wittes J, Cutler JA. The use of subjective rankings in clinical trials with an application to cardiovascular disease. Stat Med. 1992;11:427–437. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780110402. discussion 439–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hallstrom AP, Litwin PE, Weaver WD. A method of assigning scores to the components of a composite outcome: An example from the miti trial. Control Clin Trials. 1992;13:148–155. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(92)90020-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Taylor AL, Ziesche S, Yancy C, Carson P, D'Agostino R, Jr, Ferdinand K, Taylor M, Adams K, Sabolinski M, Worcel M, Cohn JN. Combination of isosorbide dinitrate and hydralazine in blacks with heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2049–2057. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa042934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hong KS, Ali LK, Selco SL, Fonarow GC, Saver JL. Weighting components of composite end points in clinical trials: An approach using disability-adjusted life-years. Stroke. 2011;42:1722–1729. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.600106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.World Health Organization. Geneva: WHO; 2004. [last accessed February 24, 2013]. Global burden of disease 2004 update: disability weights for diseases and conditions. Website www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/GBD2004_DisabilityWeights.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tong BC, Huber JC, Ascheim DD, Puskas JD, Ferguson TB, Jr, Blackstone EH, Smith PK. Weighting composite endpoints in clinical trials: Essential evidence for the heart team. Ann Thorac Surg. 2012;94:1908–1913. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2012.05.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]