Abstract

Subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE) is a rare disorder in the developed world. However, an upsurge has been seen lately in our part of the world owing to inadequate measles immunization coverage. At the midst of our struggle against polio, we are struggling with the war against other vaccine-preventable childhood illnesses like measles. The increasing numbers of SSPE that we reported over the past half decade suggest an underlying periodic measles epidemic in Pakistan. In addition, children are now presenting with SSPE in early childhood, warranting a relook, reinforcement and strengthening of primary immunization and mandatory two-dose measles vaccination for all children nationwide. Previously undertaken Measles Supplementary Immunization Activity were a failure in terms of providing the expected cover against measles in young children. Intensive surveillance and establishment of SSPE registers at the district level is essential for eradication of this easily preventable disorder. Unless timely efforts are made to achieve global immunization, SSPE is bound to add to the national disability burden.

Keywords: SSPE, measles coverage, incidence

Background

Subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE) is a progressive catastrophic neurodegenerative disease because of persistent measles viral infection in the brain [1]. SSPE manifests after 6–8 years of the clinical measles infection, placing children with a history of measles in early infancy at a higher risk. Jabbour et al.[2] have categorized the disease into four clinical stages. Initial symptoms are usually mild with intellectual deterioration and behavioral change, which later progresses to a decline in motor and cognitive function. Death usually occurs within 1–3 years once the disease is established [1]. It is confirmed by presence of measles antibody in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), the characteristic electroencephalogram (EEG) pattern or histological findings in brain biopsy. SSPE in children who do not have a history of measles is attributed to either subclinical measles infection or an undiagnosed infection in the past [1].

Measles is a disease preventable by vaccination; it primarily affects children in developing countries. SSPE is now a rare entity in the developed part of the world owing to successful routine measles immunization. In countries where effective measles control has been achieved through vaccination, a decline in new cases of SSPE is reported several years after the decline in measles; however, when epidemics occur after the good control, SSPE is reported after a delay of several years. Thus, vaccination against measles, intensive surveillance and establishment of SSPE registers have clearly reduced the incidence of SSPE through protection against measles with a reduction of 82–96% in countries where the direct comparisons between the two can be done [1]. However, for countries that are still observing high numbers of SSPE cases, low vaccine coverage, continued measles outbreaks and cold chain problems have been identified as the underlying reasons [1].

Epidemiological Evidence: Pakistan, Measles Incidence and Vaccine Coverage

Measles is endemic in Pakistan, with periodic epidemics every 2–3 years [3]. In Pakistan, estimates show that 20 000 children die annually of measles [4]. This is despite the Expanded Program on Immunization (EPI), which delivers BCG, DPT, OPV, Hib, Measles and Hepatitis B vaccines in the first year of life [4], with pneumococcal vaccine introduction in early 2012. The current target of EPI is to immunize children less than 1 year of age against nine vaccine-preventable diseases [5]. Pakistan Demographic and Health Survey reports coverage for all EPI vaccines in Pakistan to be around 47% [5]. Pakistan Social And Living Standard Measurement Survey 2004–05 reports slightly higher values [4]. A second dose of measles is now recommended by the EPI, but the coverage for this in all provinces is still very low [5]. Nonetheless in the year 2011, 88% measles coverage was reported at the national level [6], leading to a discrepancy between reported national measles vaccine coverage and independent monitoring. The reported measles vaccine coverage by independent surveys ranges between 47 and 78% during the years 1990–2007 [5]. This discrepancy may reflect the failure to vaccinate enough children, leading to periodic epidemics every second or third year; that is seen more frequently in the past 6–7 years. Infants were more likely to be affected in epidemics, leading to increased short- and long-term complications [3]. Pakistan comes under the category of poor control measles country because of its continued regular large outbreaks. There is a strong inverse correlation of measles vaccination coverage and SSPE [1]. The incidence of SSPE among measles accounts for approximately 4–11 per million children who have measles; however, if the measles infection is acquired very early in life, the risk may be even higher up to 18 per million children with measles [1, 3]. The effect of measles vaccination on the epidemiology of SSPE has been under focus for quite a few years. With the arrival of measles vaccination in 1963, there were fears of observing vaccine-induced SSPE. They were later disproved by the genetic studies that recapitulated that measles vaccine does not cause SSPE [1], and it is now widely accepted that SSPE in the absence of direct measles virus infection is not possible. SSPE in children who did not have a history of measles is attributed to either subclinical measles infection or a previously undiagnosed infection [7].

We are reporting on children who were diagnosed with SSPE in our tertiary-care hospital and comparing the trends to studies published at the national level.

Materials and Methods

Aga Khan University Hospital, Karachi, is a mainstream tertiary-care hospital catering to a wide spectrum of paediatric diseases. During June 2000–June 2012 period, a total of 43 children were discharged from the hospital with discharge diagnosis of SSPE. Cases were identified by using hospital information management system using international classification of disease-10 (ICD-10) coding A81.1 for SSPE. Demographic information (gender, age at diagnosis, history of measles and measles vaccination via routine immunization), laboratory diagnosis (clinical manifestation, EEG, CSF analysis, CSF measles IgM) along with discharge disposition were recorded.

Results

Forty-three cases of SSPE were diagnosed from the year 2000 to 2012. Diagnosis was mainly clinical with supportive evidence by EEG and presence of measles antibodies in the CSF. In all, 13 (30%) children were vaccinated for measles, 19 (44%) were unvaccinated and immunization status for 11 (26%) children was not known. Seventeen (39.5%) children had a positive history of measles. Seven (41%) of these suffered from measles at less than 1 year of age. Over the 9 year period from 2000 to 2008, a total of 19 cases of SSPE were diagnosed. A rapid rise was observed during the 4 year period (2009–2012) when 24 cases were identified, where half of them were diagnosed in the first half of 2012 only (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Trends in SSPE incidence observed at the Aga Khan University Hospital (AKUH) from 2000 to 2012.

Discussion

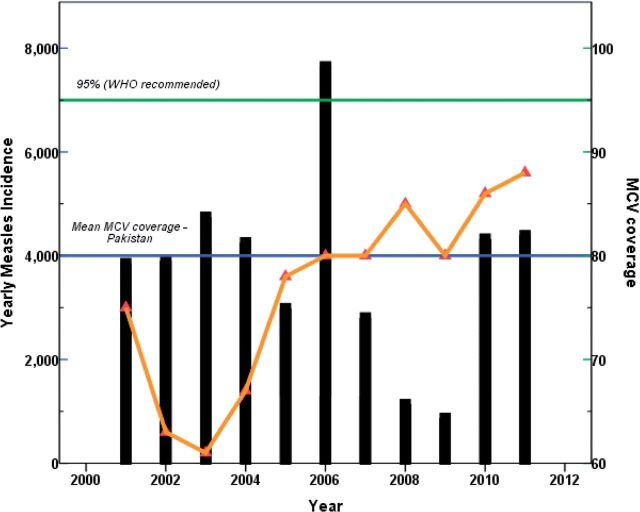

The epidemiology of natural measles infection may be reflected by the rise in SSPE incidence in Pakistan. This is predictable in the presence of unsatisfied routine measles vaccine coverage. Table 1 summarizes the SSPE reported cases from Pakistan over the years [8–11]. Retrospectively 322 SSPE cases have been reported from Pakistan. There is no registry or surveillance system in Pakistan either for SSPE or for measles. Therefore we think that there is a marked under reporting and underestimation of SSPE and Measles. On the assumption that the risk of SSPE may be higher up to 18 per million children affected with measles an estimated 17.8 million children may have been affected by measles in the last two decades in Pakistan. Kondo et al.reported that SSPE represented about 10% of neurological diseases observed in children in Karachi [12]. Important diagnostic tools for SSPE are not widely available in Pakistan. Only very few centres could do measles antibody testing. Authors also believe this could be one of the reasons for underestimation of SSPE. Emphasis is now being given on early diagnostics regarding SSPE; although the diagnosis is mainly clinical, supportive evidence from EEG and CSF measles antibody is now routine at most tertiary-care centres. The children diagnosed at our centre underwent a CSF testing for measles antibody and were positive in all cases. However, in limited-resource setting like ours, SSPE is underreported owing to lack of diagnostics in most health-care centres. The 43 cases that we are reporting are from one centre and do not reflect the true disease burden. However, enhanced diagnostic facilities can help identify more cases of SSPE and improve surveillance at national level. What is noteworthy is the fact that 66.6% of children diagnosed with SSPE over the past 4 years were unvaccinated. This further supports the fact that there are pitfalls in the national vaccination program that need to be looked into at through EPI every year [5]. According to a World Bank report published in 2012, measles vaccination coverage in children 12–23 months of age in Pakistan was about 86% in 2010 [13]; however, a recently published Pakistan Demographic and Health Survey 2012–13 reported 49% MCV1 coverage at infancy. [14]. However, if we review the national measles immunization coverage over the past 12 years, figures range from 59 to 73% for the first dose of measles vaccine. The coverage is even lower for the second dose of measles vaccine, decreasing to 30–58% [15]. The rise in the reported cases of SSPE can be attributed to the poor vaccine coverage in the past decade (Fig. 2). The suboptimal measles vaccine coverage in 2003 correlates with the rising numbers of SSPE cases seen at our hospital, consistent with the natural trend of the course of the disease. What is noteworthy is that about 40% of the children who were diagnosed with SSPE suffered from measles at less than 1 year of age; this implied that children were acquiring measles before the first dose of measles vaccine was administered at 9 months of age [3], stressing high vaccine coverage of MCV1 at 9 months of age [16]. Of the 43 children diagnosed with SSPE over the past 12 years, the mean age was around 8.9 years, with the youngest child being diagnosed at 3 years of age. In all, 84% of children were less than 10 years of age, showing a change in the clinical trend of the disease. Earlier, SSPE would manifest in children more than 10 years of age; the disease affecting them 5–7 years after measles infection. The earlier presentation of SSPE could represent a changing epidemiology of the disease. We outlined a time trend analysis of the measles cases observed over the past decade and compared them with the national measles immunization coverage during that period. However, we had limitation regarding the comparison of SSPE cases over this period owing to the scarce data available at national level. However, the reported SSPE cases from Pakistan have been summarized in the Table 1. We can only compare the cases we diagnosed at our hospital in regard to the clinical picture and epidemiology. Comparison of SSPE trends at the national level is difficult with the limited data gathered at one centre.

Table 1.

| Year published | Duration | Number of confirmed casesd | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2011, Malik MA et al. [8]b | 2008–10 | 96 | Measles Hx. <2 years of age (n = 43, 45%) |

| Confirmed measles serology in CS Measles CSF IgM (n = 40, 42%) | |||

| 2008, Akram M et.al., [9] | 2005–07 | 50 | Mean age: 8 years |

| Average duration of symptoms before presentation = 66.7 days | |||

| Measles Hx (n = 31, 62%) | |||

| Received measles vaccine (n = 43, 86%) | |||

| Measles CSF IgM (n = 50, 100%) | |||

| 2001, Tariq WUZ [10] | – | 89 | Measles CSF IgM (n = 11, 12%) |

| 1992, Takasu T et.al. [11] | 1983–88 | 44 | Early age of measles in SSPE cases |

| <2 years of age (15/44 cases) | |||

| 2012, Ibrahim S et.al., (current study) | 2000–12 | 43 | Males (n = 31) predominance |

Assumption of 18 SSPE cases per million measles cases, then affected measles children leading to this SSPE cases calculated to be more than 17 million for Pakistan in past two decades.

Hx, history.

aPubMed.

bNon-indexed publication.

c322 SSPE cases.

dConfirmed on clinical features, EEG and positive CSF measles serology.

Fig. 2.

Time trend analysis of measles cases and MCV (measles containing vaccine) coverage in Pakistan from 2000 to 2012 (Courtesy: Saleem, AF).

Regarding the immunization failure at the national level, multiple factors have been identified, improper administration and substandard cold chain maintenance of vaccines being most common [17]. Routine measles surveillance is being done at the district, provincial and national level to investigate suspected outbreaks, identify populations at risk, analyse data for epidemiological trends and evaluate control measures for improved surveillance in future. Efforts are being made to strengthen the surveillance system and achieve universal immunization to make Pakistan a measles free zone. The WHO and UNICEF have increased the funding for childhood immunization in Pakistan, and notably more than half of the funding is spent on polio eradication campaigns [18]. In addition to the EPI schedule, regular national polio campaigns are run across the country to immunize children against polio virus. This might be the reason for the recently observed rise in measles countrywide. In the hue for polio eradication, measles immunization appears to have suffered neglect. Massive campaigns at the national level are now required to raise the measles vaccine coverage to satisfactory grounds so that the rising numbers of SSPE are brought to halt.

Conclusion

This alarming rise in SSPE is attributed to the poor measles vaccination among our children and calls for immediate attention towards achieving global immunization. The young age at which children are being affected by measles warrants revision of the current immunization schedule being followed in the country. There are data to support the introduction of early measles vaccination in endemic areas [16]. Unless timely efforts are made, we are bound to see more SSPE in the coming decade that will further accentuate the national disease burden.

Acknowledgements

Dr. Ali Faisal Saleem received research training support from the National Institute of Health’s Fogarty International Center (1 D43 TW007585-01).

References

- 1.Campbell H, Andrews N, Brown KE, et al. Review of the effect of measles vaccination on the epidemiology of SSPE. Int J Epidemiol. 2007;36:1334–48. doi: 10.1093/ije/dym207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jabbour JT, Garcia JH, Lemmi H, et al. Subacute sclerosing panencephalitis. A multidisciplinary study of eight cases. JAMA. 1969;207:2248–54. doi: 10.1001/jama.207.12.2248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saleem AF, Zaidi A, Ahmed A, et al. Measles in children younger than 9 months in Pakistan. Indian Pediatr. 2009;46:1009–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mitchell S, Andersson N, Ansari NM, et al. Equity and vaccine uptake: a cross-sectional study of measles vaccination in Lasbela District, Pakistan. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2009;9(Suppl. 1):S7. doi: 10.1186/1472-698X-9-S1-S7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hasan Q, Bosan AH, Bile KM. A review of EPI progress in Pakistan towards achieving coverage targets: present situation and the way forward. East Mediterr Health J. 2010;16(Suppl):S31–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. http://www.who.int/immunization monitoring/diseases/measles/en/index.html.

- 7.Bellini WJ, Rota JS, Lowe LE, et al. Subacute sclerosing panencephalitis: more cases of this fatal disease are prevented by measles immunization than was previously recognized. J Infect Dis. 2005;192:1686–93. doi: 10.1086/497169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Malik MA, Tarar MA, Qureshi MS, et al. Subacute sclerosing panencephalitis in Pakistani children presenting for a first EEG. Pak Paed J. 2011;35:185–91. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Akram M, Naz F, Malik A, et al. Clinical profile of subacute sclerosing panencephalitis. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2008;18:485–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tariq WUZ, Waqar T, Ghani E. Subacute sclerosing panencephalitis—a Pakistan perspective. Trop Doct. 2001;31:110. doi: 10.1177/004947550103100222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Takasu T, Kondo K, Ahmed A, et al. Elevated ratio of late measles among subacute sclerosing panencephalitis patients in Karachi, Pakistan. Neuroepidemiology. 1992;11:282–7. doi: 10.1159/000110942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kondo K, Takasu T, Ahmed A. Neurological diseases in Karachi, Pakistan—elevated occurrence of subacute sclerosing panencephalitis. Neuroepidemiology. 1988;7:66–80. doi: 10.1159/000110138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. http://www.tradingeconomics.com/pakistan/immunization-measles-percent-of-children-ages-12-23-months-wb-data.html. (23 January 2013, date last accessed)

- 14.National Institute of Population Studies (NIPS) [Pakistan] and ICF International. Pakistan Demographic and Health Survey 2012-13. Islamabad, Pakistan, and Calverton, MD, USA: NIPS and ICF International; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 15.MCV Coverage WHO. http://apps.who.int/immunization_monitoring/timeseries/tscoveragemcv.html (18 July 2014, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aaby P, Andersen M, Sodemann M, et al. Reduced childhood mortality after standard measles vaccination at 4-8 months compared with 9-11 months of age. BMJ. 1993;307:1308–11. doi: 10.1136/bmj.307.6915.1308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sheikh S, Ali A, Zaidi AK, et al. Measles susceptibility in children in Karachi, Pakistan. Vaccine. 2011;29:3419–23. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.02.087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Childhood Immunization in Pakistan.Research and Development Solutions. 2012. (Policy Briefs Series No. 3). [Google Scholar]