Abstract

Background

A large proportion of children younger than five years of age in high‐income countries experience significant non‐parental care. Centre‐based day care services may influence the development of children and the economic situation of parents.

Objectives

To assess the effects of centre‐based day care without additional interventions (e.g. psychological or medical services, parent training) on the development and well‐being of children and families in high‐income countries (as defined by the World Bank 2011).

Search methods

In April 2014, we searched CENTRAL, Ovid MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycINFO, the Education Resources Information Center (ERIC) and eight other databases. We also searched two trials registers and the reference lists of relevant studies.

Selection criteria

We included randomised and quasi‐randomised controlled trials of centre‐based day care for children younger than five years of age. We excluded studies that involved co‐interventions not directed toward children (e.g. parent programmes, home visits, teacher training). We included the following outcomes: child cognitive development (primary outcome), child psychosocial development, maternal and family outcomes and child long‐term outcomes.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently assessed the risk of bias and extracted data from the single included study. We contacted investigators to obtain missing information.

Main results

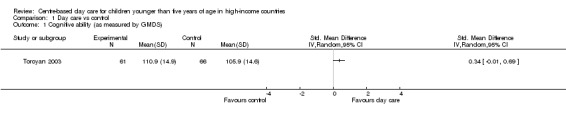

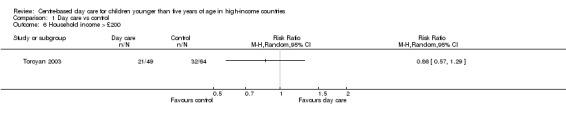

We included in the review one trial, involving 120 families and 143 children. Risk of bias was high because of contamination between groups, as 63% of control group participants accessed day care services separate from those offered within the intervention. No evidence suggested that centre‐based day care, rather than no treatment (care at home), improved or worsened children's cognitive ability (Griffiths Mental Development Scale, standardised mean difference (SMD) 0.34, 95% confidence interval (CI) ‐0.01 to 0.69, 127 participants, 1 study, very low‐quality evidence) or psychosocial development (parental report of abnormal development, risk ratio (RR) 1.21, 95% CI 0.25 to 5.78, 137 participants, 1 study, very low‐quality evidence). No other measures of child intellectual or psychosocial development were reported in the included study. Moreover, no evidence indicated that centre‐based day care, rather than no treatment (care at home), improved or worsened employment of parents, as measured by the number of mothers in full‐time or part‐time employment (RR 1.12, 95% CI 0.85 to 1.48, 114 participants, 1 study, very low‐quality evidence) and maternal hours per week in paid employment (SMD 0.20, 95% ‐0.15 to 0.55, 127 participants, 1 study, very low‐quality evidence) or household income above £200 per week (RR 0.86, 95% CI 0.57 to 1.29, 113 participants, 1 study, very low‐quality evidence). This study did not report on long‐term outcomes for children (high‐school completion or income).

Authors' conclusions

This review includes one trial that provides inconclusive evidence as regards the effects of centre‐based day care for children younger than five years of age and their families in high‐income countries. Robust guidance for parents, policymakers and other stakeholders on the effects of day care cannot currently be offered on the basis of evidence from randomised controlled trials. Some trials included co‐interventions that are unlikely to be found in normal day care centres. Effectiveness studies of centre‐based day care without these co‐interventions are few, and the need for such studies is significant. Comparisons might include home visits or alternative day care arrangements that provide special attention to children from low‐income families while exploring possible mechanisms of effect.

Plain language summary

Centre‐based day care for children younger than five years of age in high‐income countries

Review question

This review evaluated the effects of centre‐based day care on the cognitive and psychosocial development of children younger than five years of age and the economic situation of their parents in high‐income countries (as defined by the World Bank 2011). We defined 'centre‐based day care' as supervision of children in a publicly accessible location.

Background

A large proportion of children younger than five years of age in high‐income countries experience significant non‐parental care. Centre‐based day care services may influence the development of children and the economic situation of parents.

Study characteristics

We included studies that assessed the effects of centre‐based day care for children younger than five years of age in high‐income countries. To isolate the effects of day care, we excluded interventions that involved medical, psychological or non–child‐focused co‐interventions. Electronic searches identified 34,890 citations that were screened for inclusion in the review. Only one study (120 families, 143 children), based in London, England, matched all inclusion criteria and was included in the review. Evidence is current to April 2014.

Key results

Currently very limited evidence is available on the effects of centre‐based day care on the cognitive and psychosocial development of children, parental employment or household income, or on long‐term outcomes for children.

Quality of the evidence

Only one randomised controlled trial (RCT) was included in this review. In addition, a large proportion of families in the non‐intervention group secured day care services for themselves. The quality of the evidence included in this review is very low, so the results must be interpreted with caution. Although RCTs do not allow conclusive judgements as regards the role of centre‐based day care in the development of children and the economic situation of parents, this does not imply that these services are not important in high‐income countries. The need for effectiveness studies of centre‐based day care without co‐interventions is significant.

This review is one of a pair of reviews; researchers and practitioners may find evidence from the low‐ and middle‐income country review to be informative also (Brown 2014).

Summary of findings

for the main comparison.

| Centre‐based day care compared with no intervention (care at home) for children younger than five years of age | ||||||

| Patient or population: children younger than five years of age and their families Settings: high‐income countries (N.B. relevant evidence comes from a study conducted in a highly disadvantaged area with a large refugee population in London, United Kingdom) Intervention: centre‐based day care Comparison: no intervention (alternative child care) | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Control | Day care | |||||

| Child cognitive ability As assessed by the Griffith Mental Development scale at 18‐month follow‐up | Mean quotient in the control group was 105.9 (102.93 to 108.86) | Mean quotient in the intervention group was 5.0 higher (107.75 to 114.05) | SMD 0.34 (‐0.01 to 0.69) | 127 (1) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowa | 127 children were assessed by a paediatrician at 18‐month follow‐up. Scores on this outcome were obtained through these assessments |

| Child psychosocial development Parents reporting their child develops abnormally | 4.0 per 100 (3 per 75) | 4.8 per 100 (3 per 62) |

RR 1.21

(0.25 to 5.78) (RR 0.88, 0.29 to 2.65)b |

137 (1) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowa | 114 mothers completed the follow‐up questionnaire at 18 months. Reports on this outcome were submitted for 137 children |

| Paid maternal employment Mothers in full‐time or part‐time employment | 60 per 100 (39 per 65) | 67.3 per 100 (33 per 49) |

RR 1.12

(0.85 to 1.48) (RR 1.14, 0.86 to 1.53)b |

114 (1) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowa | No comments |

| Paid maternal employment Maternal hours per week in paid employment | Mean number of hours in the control group was 11.4 (8.10 to 14.70) | Mean number of hours in the intervention group was 3.4 higher (11.21 to 18.39) | SMD 0.20 (‐0.15 to 0.55) | 127 (1) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowa | No comments |

|

Household income Households with weekly income > £200 |

50 per 100 (32 per 64) |

42.9 per 100 (21 per 49) |

RR 0.86

(0.57 to 1.29) (RR 0.89, 0.59 to 1.34)b |

113 (1) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowa | |

| CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio; SMD: standardised mean difference (Hedges' g) | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

aAs the result of serious imprecision and very serious risk of bias.

bEffect sizes when imputing data for missing cases (assuming negative outcomes for missing cases in all groups).

Background

Description of the condition

A large proportion of children younger than five years of age in high‐income countries experience significant non‐parental care. Specifically, an estimated 80% of children in the United States regularly attend day care (NICHD ECCRN 2006), and similar figures have been reported for the United Kingdom and Australia (CCCH 2009; Smith 2010). In addition, almost 50% of children three to four years of age in the United States are in full‐time day care (at least 35 hours a week) (Capizzano 2005). Parents often choose day care for economic reasons (e.g. to enable them to work, look for work, or study) (Smith 2010). For the estimated 20% of single‐parent families in high‐income countries (OECD 2013), child care may be particularly pertinent. In addition, parents might choose day care to improve their child’s social and academic skills before entry into formal schooling (Lamb 2006). Finally, centre‐based day care can serve as the setting for early interventions to target and enhance the social, cognitive, and academic development of disadvantaged young children (Campbell 2001).

Description of the intervention

Day care for children in high‐income countries takes various forms and may serve multiple purposes. For children younger than three years of age, services tend to be care‐oriented and include care by professionals, child minders and day nurseries. For children three years of age and older, day care programmes include more focused educational aims and include preschools, playgroups and nursery classes (Melhuish 2004). The quality, quantity and type of day care service appear to be differentially related to child outcomes (NICHD ECCRN 2005; Belsky 2007). Therefore, although increasing overlap between education‐ and care‐focused services has been noted, it is important to distinguish between studies assessing children younger than three years of age and those assessing children older than three years, as the nature of the services provided and consequently the results may differ. It is also important to distinguish between formal centre‐based care (e.g. nursery schools, preschools) and informal care (e.g. care provided by an ex‐partner or grandparent) and to consider whether the effectiveness of care provided differs across settings, including rural versus urban settings or areas of high versus low socioeconomic status (Smith 2010). In addition to differences across settings and types of services provided, the explicit purposes for day care can differ. First, day care enables parental, specifically maternal, employment. Provision of day care is correlated with increased female participation in the labour force in high‐income countries (Gelbach 2002; Esping‐Andersen 2009). Second, day care may impact the long‐term cognitive and socioemotional development of children, particularly children from deprived homes (Dearing 2009).

How the intervention might work

Day care may enrich the physical and emotional environment of children, providing benefit for the development of children in impoverished circumstances. Some studies have found that day care improves social competence (e.g. Clarke‐Stewart 1994; Balleyguier 1996), and this may have lasting effects on mental health outcomes (Shonkoff 2011). However, day care may also involve adverse effects. Longitudinal studies have found that day care increases externalising behavior, including aggression and non‐compliance (NICHD ECCRN 2006; Philips 2006; Belsky 2007). Other studies suggest that it may disrupt a secure mother‐child attachment (Ainsworth 1978, Sroufe 1999).

Day care may serve to directly enhance child outcomes via cognitive development, and this may have collateral effects on future educational attainment and adult outcomes. Specifically, school readiness and cognitive capacities appear to be enhanced by structured activities, psychosocial stimulation (NICHD ECCRN 2006) and the presence of responsive, verbally articulate staff within day care settings (Melhuish 2004). High‐quality centre‐based care has also been linked to improved language development (Clarke‐Stewart 1987; Schliecker 1991). In particular, language learning appears to be facilitated in day care settings when children are afforded increased opportunities to interact verbally with adults and peers. Longitudinal studies have demonstrated that early experience in high‐quality day care as part of multi‐component interventions, particularly for low‐income children, predicts better academic outcomes, higher rates of employment and less adult criminal activity (e.g. Schweinhart 1993; Campbell 2001). At the same time, other studies have found poorer language development to be associated with increased day care experience (Brooks‐Gunn 2002; Bainbridge 2003). Indeed, low‐quality day care settings may be seen to include large numbers of children cared for by few and underresourced staff members, thereby reducing the potential effectiveness of day care as an intervention to improve child psychosocial or cognitive outcomes (Raver 2004).

Finally, day care is offered as a means of improving household income. Mothers may be able to participate more fully in the labour market when they feel that their children are secure and cared for (Vandell 2002; Melhuish 2004). Indeed, provision of day care is correlated with increased female participation in the labour force in high‐income countries and earlier return to the workforce after pregnancy (Brooks‐Gunn 1994; Gelbach 2002; Esping‐Andersen 2009). Indirect effects of improved household income on child outcomes are likely and include improved nutrition and a more enriched home environment.

Why it is important to do this review

A significant proportion of children younger than five years of age in high‐income countries experience significant non‐parental day care within formal and informal settings (NICHD ECCRN 2006; Smith 2010). Although services may vary across settings and for different age groups, formal day care directly targets participating children within a defined centre‐based setting. It is important for researchers to evaluate the specific effects of day care (i.e. day care without additional components that are not centre‐based or targeted at children) on the cognitive, linguistic, educational, socioemotional, attachment and physical health outcomes of children, as well as its impact on parental employment and family income.

Previous reviews of centre‐based day care or childhood education have not employed systematic methods or have not focused on day care as a stand‐alone intervention without additional components, such as home visits or other interventions that are not centre‐based (Lazar 1982; Belsky 1988; Gorey 2001; Melhuish 2004; Burger 2010; Camilli 2010). The only Cochrane review on the topic (Zoritch 2000) also included co‐interventions beyond day care, limiting conclusions regarding the effects of day care services alone. To best understand its effects, researchers must isolate the intervention of centre‐based day care from other such services. The effects of additional components that are centre‐based (e.g. educational programmes) also need to be analysed. Finally, possible social and economic confounding variables must be controlled for, as specified in the content of this review. This review, in conjunction with a review of studies of day care for children in low‐ and middle‐income countries (Brown 2014), replaces the previous review.

Objectives

To assess the effects of centre‐based day care without additional interventions (e.g. psychological or medical services, parent training) on the development and well‐being of children and families in high‐income countries (as defined by the World Bank 2011).

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials and quasi‐randomised controlled trials.

Types of participants

Children younger than five years of age (at the time of enrolment) and their families in high‐income countries.

Types of interventions

We included centre‐based day care, defined as supervision of children in a publicly accessible location, with or without snack and meal provision, a child education component or both.

We excluded studies of day care with medical or psychological co‐interventions unless these were also received by participants in control groups. We also excluded studies involving co‐interventions not directed toward children or not centre‐based (e.g. parent programmes, home visits, teacher training), as the presence of such co‐interventions would weaken the extent to which findings can be attributed to centre‐based care alone. Finally, we excluded studies in which enrolment was limited to children with physical or intellectual disabilities (e.g. autism, IQ less than 80), orphaned children, children living in hospitals or children living with HIV or AIDS.

Types of outcome measures

We assessed the effects of centre‐based day care on outcomes of child and family well‐being by extracting data on the outcomes listed below. For studies reporting more than one measure of an outcome, we extracted data using methods described in successive sections (see Measures of treatment effect). We included primary outcomes and the first secondary outcome in Table 1.

Primary outcomes

Child intellectual development.

Cognitive ability (e.g. IQ, developmental quotient).

Attainment of educational goals (e.g. measures of reading, writing, or mathematics; retention in grade).

Child psychosocial development.

Any behavioural measure (e.g. self, parent and teacher reports of externalising behaviour or aggression; prosocial or antisocial behavior).

Disrupted child attachment to mother (e.g. using the Stange Situation (Ainsworth 1978) measurement or the Disturbances of Attachment Interview (Smyke 1999)).

Secondary outcomes

Maternal and family outcomes.

Paid parental employment (e.g. in paid work, on maternity or paternity leave, hours per week in paid work).

Household income (e.g. weekly or annual income range).

Child long‐term outcomes.

High school completion.

Income (e.g. weekly or annual income range).

Search methods for identification of studies

We considered all studies returned by the search strategy (see Appendix 1) irrespective of date, language or publication status. We conducted all searches and author communications in English.

Electronic searches

We searched the following databases on 24 April 2014.

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) 2014 (Issue 4), part of The Cochrane Library.

Ovid MEDLINE(R) 1946 to April Week 2 2014.

EMBASE (Ovid) 1974 to April Week 2 2014.

Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI) (Web of Science) 1956 to 24 April 2014.

PsycINFO (Ovid) 1967 to April Week 2 2014.

Education Resources Information Center (ERIC) (http://eric.ed.gov/) 1966 to 24 April 2014.

Global Health Library (Ovid) 1973 to 24 April 2014.

Conference Proceedings Citations Index–Social Science & Humanities (CPCI‐SSH) 1990 to 24 April 2014.

SCOPUS to 24 April 2014.

ZETOC (http://zetoc.mimas.ac.uk/) 1993 to 24 April 2014.

Open Access ProQuest Dissertations & Theses (PQDT Open) (http://pqdtopen.proquest.com) to 24 April 2014.

Population Information Online (POPLINE) (www.popline.org/) 1973 to 25 April 2014.

OpenGrey (www.opengrey.eu/) to 25 April 2014.

ClinicalTrials.gov to 24 April 2014.

International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) (www.who.int/ictrp/en/) to 24 April 2014.

Searching other resources

We examined reference lists from previous relevant studies. We contacted the authors of all included studies to request details of ongoing and unpublished studies.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (FvU and TWB) independently screened all titles and abstracts. They collected and independently screened relevant articles to determine which studies met the inclusion criteria. Disagreements were resolved through discussion and consultation with other review authors (RW and EMW).

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (FvU and TWB) independently extracted the following data from all included studies.

General information

Year of study.

Country of study.

Study design (i.e. case control, cohort).

Unit of analysis (e.g. individual‐ or cluster‐randomised).

Methods used to control for confounding factors.

Setting of study (i.e. urban or rural, specific region or city if provided).

Participants

Number of study participants and clusters randomly assigned to each included group.

Age.

Sex.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Household income (if reported).

For each intervention or comparison group of interest

Dose of centre‐based care.

Duration of centre‐based care.

Frequency of centre‐based care.

Co‐interventions provided (if any).

Quality of care provided (if measured).

For each study, we used lists for identifying study design as recommended by The Cochrane Collaboration (Higgins 2011).

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (FvU and TWB) coded each included study using the Cochrane tool for assessing risk of bias (Higgins 2011; Section 8.5.a) across the following domains: sequence generation; allocation concealment; blinding of study participants, personnel and outcome assessors; incomplete outcome data; selective outcome reporting; and other sources of bias. In addition to these, we accounted for risk of bias due to confounding and for outcome validity (see Table 2). We assigned each category a rating of low, high or unclear risk of bias based on criteria for judging risk of bias provided by the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions and included in the 'Risk of bias' assessment tool (Higgins 2011; Section 8.5.c). A rating of low indicated that evidence was sufficient to judge that study authors used appropriate methods to avoid bias; a rating of high indicated that evidence was sufficient to judge that study authors did not use appropriate methods to avoid bias; and a rating of unclear indicated that information was insufficient to judge the extent to which study authors used appropriate methods to avoid bias.

1. Risk of bias due to possible confounders.

| Toroyan 2003 | ||

| Potential confounder | Authors’ judgement | Support for judgement |

| Age of child | Low risk | The mean age of children whose mother had completed the baseline questionnaire was 25.5 months (SD = 10.1) and 25.7 months (SD = 10.2) for the intervention and control groups respectively. It is unlikely that results were confounded by differences in children's ages between comparison groups |

| Sex of child | Unclear risk | The sex of children was not reported for either of the comparison groups |

| Household income | Unclear risk | The percentage of families with a weekly household income greater than £200 at baseline was 42% for the intervention group and 38% for the control group. However, the mean household income for both groups is not reported |

| Quality of day care centre | High risk | The day care centre that delivered the treatment to the intervention group was of unusually high quality, exceeding British national requirements for standard indicators such as staff qualifications and staff‐to‐child ratios. The centre also offered parents full‐time or part‐time places with the option to change depending on circumstances. In addition, education was integrated into the care of the children. The risk is high that estimates of effects were larger than would have been the case had day care of average quality been compared with no treatment. |

| Fees of day care centre | Unclear risk | At the outset of the study, fees were £70 per week for each child younger than two years of age. During this study, this increased to £125 as a result of financial constraints that were caused by a 3‐month freeze on spending in all local authority‐run nurseries. This freeze of spending was a result of the bankruptcy of the Borough of Hackney in 2000 (the study was undertaken between 1998 and 2002). How this may have affected the results is unclear |

SD = standard deviation.

We resolved disagreements as regards the 'Risk of bias' assessment process through discussion with a third review author (EMW).

Measures of treatment effect

We calculated risk ratios (RRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for dichotomous outcomes. We used Hedges' (adjusted) g (a standardised mean difference (SMD)) for each outcome for which continuous data were available. For a full overview of the measures of treatment effect that were originally proposed, please see Appendix 2 and the protocol of this review (Van Urk 2013). We used Review Manager (RevMan) Version 5.1 (Review Manager 2012) to conduct all analyses.

Unit of analysis issues

Data in this review were derived from one cluster‐randomised controlled trial, in which groups rather than individuals were randomly assigned. We determined that this trial incorporated sufficient controls for clustering (robust standard errors, bootstrap confidence intervals for highly skewed continuous outcome data). For a detailed description of this study, see the Characteristics of included studies table. For a full overview of the methods originally proposed for dealing with unit of analysis issues and that may be used in future updates of this review, please see Appendix 2 and the protocol of this review (Van Urk 2013).

Dealing with missing data

For all analyses, we attempted to include all study participants, and we contacted study authors to request data, including those on all participants randomly assigned for all outcomes. We contacted study authors for additional information regarding reasons for missing participant data and reasons for dropout of participants but received no response. For studies reporting dichotomous data, we conducted a Sensitivity analysis to determine the sensitivity of results against missing data. We described all missing data in the 'Risk of bias' table.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We did not assess heterogeneity because only one study met the inclusion criteria. For a full overview of the methods originally proposed for assessment of heterogeneity and that may be used in future updates of this review, please see Appendix 2 and the protocol of this review (Van Urk 2013).

Assessment of reporting biases

We did not assess reporting biases because only one study met the inclusion criteria. For a full overview of methods originally proposed for assessment of reporting biases and that may be used in future updates of this review, please see Appendix 2 and the protocol of this review (Van Urk 2013).

Data synthesis

The proposed primary meta‐analysis consisted of all centre‐based day care programmes versus non–centre‐based child care (e.g. home care by a parent). We were unable to combine outcome data in a meta‐analysis because only one study was included. For a full overview of the methods oriiginally proposed for data synthesis and that may be used in future updates, please see Appendix 2 and the protocol of this review (Van Urk 2013).

GRADE

We summarised the evidence in Table 1, in which we reported comparative risks for each primary outcome and for the first secondary outcome. We used the GRADE (Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation) approach to assess the quality of the evidence, using the criteria reported in Section 12.2.2 of Higgins 2011.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We did not conduct subgroup analyses because only one study met the inclusion criteria, and no data were provided for the subgroups prespecified in the protocol of this review. For a full overview of the methods originally proposed for subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity, please see Appendix 2 and the protocol of this review (Van Urk 2013).

Sensitivity analysis

We performed sensitivity analyses for dichotomous outcomes for which data were missing. These involved repeating the main analyses (see Effects of interventions) with and without imputed data for missing cases. When imputating missing data, we assumed negative outcomes for those participants for whom data were missing. For a full overview of the sensitivity analyses originally proposed, please see Appendix 2 and the protocol of this review (Van Urk 2013).

Results

Description of studies

We included one study in this review. We present the results of the trial selection process in Figure 1.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Results of the search

Electronic searches identified 36,853 records. Additionally, 11 records were obtained by searching reference lists. After duplicates were removed, 34,890 records were screened for this review. We assessed 38 full‐text records, related to 14 unique studies, for eligibility for this review.

Included studies

One study, reported in three articles, met all of the inclusion criteria (Toroyan 2003). Detailed characteristics of this study, including a 'Risk of bias' assessment, are provided in the Characteristics of included studies table. The study setting was the London Borough of Hackney, described by study authors as a highly disadvantaged urban area with a large refugee population. At the outset of the study, the demand for day care services in the area was excessive, with about eight children for every available place. This resulted in oversubscription to the day care centre that served as the setting for the study. A total of 120 families with 143 children were randomly assigned to receive centre‐based day care (n = 51 families, involving 64 children) or no treatment (n = 69 families, involving 79 children). In families with more than one child, all children received the same treatment. At baseline, mothers' mean age was 31.9 years and the mean age of children was 25.6 months. Children in the intervention group received high‐quality day care with qualified teaching staff, flexible places (full‐time or part‐time places with the option to change depending on circumstances) and a strong focus on education. Fees were initially £70 per week for each child younger than two years of age, but these increased to £125 as a result of financial constraints that manifested during the study (see Table 2 Risk of bias due to possible confounders). Subsidised placement depended on the economic situation of individual families. Children in the control group received no treatment as part of the study, although many children in the control group (63%) accessed centre‐based day care during the study period. Three outcomes of relevance to this review were addressed: general intellectual development of the child (Griffiths Mental Development Scale, see Griffiths 1954), maternal employment (full‐time or part‐time, or not; number of hours worked per week) and child development as rated by mothers. All outcomes were assessed at 18‐month follow‐up. A total of 114 families with 127 children were retained at follow‐up (centre‐based day care = 49 families and 61 children; control = 65 families and 66 children).

Excluded studies

In total, we excluded 34,852 records on the basis of their title or abstract. We excluded a further 13 studies, presented in 35 reports, after accessing and evaluating the full‐text reports. Of these, we excluded nine studies because they included co‐interventions (Gray 1970; Deutsch 1971; Garber 1973; Bronson 1984; Schweinhart 1986; Wasik 1990; Brooks‐Gunn 1994; Campbell 1994; Love 2005), two studies that were not RCTs or quasi‐RCTs (Palmer 1983; Cooper 1998) and two studies in which the assigned control condition included centre‐based day care (Aunio 2005; Gallagher 2009). We described these reasons for exclusion in detail in the Characteristics of excluded studies tables.

Risk of bias in included studies

We described the results of the risk of bias assessment of the single included study in the 'Risk of bias' table and summarised these assessments in Figure 2.

2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for the included study

In summary, the risk of bias was judged to be low in relation to selection bias and high in relation to performance bias (inherent in the nature of the intervention). Risk of bias due to outcome assessor bias and attrition bias was judged unclear. The study was also judged unclear in relation to reporting bias, given that the trial was not registered and no protocol was published before results were reported. A significant limitation of the included study is the high risk of bias due to contamination. Specifically, 63% of the control group received some form of centre‐based day care (i.e. care accessed separately from that offered within the intervention) at some point during the study and before follow‐up assessment. Therefore, this study may have underestimated the magnitude of the intervention effects.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Effects of day care on outcomes relevant for this review as addressed in the included study are presented below. Because this review includes only one study, no pooled ('total') effect sizes were calculated.

Primary outcomes

Child intellectual development

Cognitive ability

The included study used the Griffiths Mental Development Scale (Griffiths 1954) to assess cognitive ability. Point estimate mean differences were adjusted for baseline values. At 18‐month follow‐up, no difference was noted between children's scores in the intervention and control groups (SMD 0.34, 95% CI ‐0.01 to 0.69, 127 participants, 1 study).

The included study did not report other child intellectual development outcomes of interest .

Child psychosocial development

Parent‐reported child psychosocial development

Mothers were asked if their child was developing abnormally, and no difference was noted between scores for the intervention and control groups (RR 1.21, 95% CI 0.25 to 5.78, 137 participants, 1 study).

The included study did not report other child psychosocial development outcomes of interest.

Sensitivity analysis

Imputing data for missing participants (assuming negative outcomes for those participants for whom data were missing) did not reveal a different effect (RR 0.88, 95% CI 0.29 to 2.65, 143 participants, 1 study).

Secondary outcomes

Maternal and family outcomes

Paid parental employment

The included study assessed maternal employment. No difference was reported between mothers in the intervention group and mothers in the control group with regards to their probability of being in full‐time or part‐time employment (adjusted RR 1.12, 95% CI 0.85 to 1.48, 114 participants, 1 study). No evidence suggested a difference in hours worked per week (SMD 0.20, 95% CI ‐0.15 to 0.55, 127 participants, 1 study).

Household income

Households in the intervention group and in the control group did not differ significantly in reporting a household income above £200 (adjusted RR 0.86, 95% CI 0.57 to 1.29, 113 participants, 1 study).

Sensitivity analysis

Imputing data for missing participants (assuming negative outcomes for those participants for whom data were missing) did not reveal a different effect for paid parental employment (RR 1.14, 95% CI 0.86 to 1.53, 120 participants, 1 study) or for household income (RR 0.89, 95% CI 0.59 to 1.34, 120 participants, 1 study).

Child long‐term outcomes

The included study did not provide data on children's high school completion or income in later life.

Discussion

Summary of main results

This review is the first systematic review of randomised controlled trials undertaken to assess the effects of centre‐based day care without additional components for children and families in high‐income countries. It included one randomised controlled trial (Toroyan 2003), which examined the effects of centre‐based day care in an area of North London with low socioeconomic status. Results from this trial, and therefore of our analysis, are of low statistical power and do not provide conclusive evidence regarding any effects of day care on children's cognitive and psychosocial development, or on parental employment and income.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

The inclusion of only one study in a high‐poverty area of North London limits applicability of the evidence provided in this review to wealthier groups, rural areas and countries with greater or lesser provision of social welfare.

Quality of the evidence

As our analysis is based on a single study, it provides insufficient power for a valid estimation of the effects of day care. In addition, the included study is at low risk of selection bias because adequate random allocation and concealment of allocation were reported. However, it is at high risk of bias across some other domains. Given the nature of the intervention, neither staff nor participants were blind to participants' assigned condition. Although some child outcomes were assessed by a paediatrician who was blind to participants' condition, some child outcomes and all maternal outcomes were self‐reported by mothers. Attrition was unevenly distributed between the intervention and control groups with regard to paediatrician‐assessed child outcomes. Reasons for this uneven distribution were not reported. The study was judged to be at high risk of bias as the result of 63% contamination of the control group. A potential explanation for this might be the relatively high age of mothers (31.9 years) included in the study, as these women may be more capable of funding their own day care services. As a result of the high risk of several sources of bias and of the imprecise results presented in the included study, GRADE quality of evidence ratings were judged to be very low for all outcomes. The quality of evidence has been judged, therefore, to be insufficient to allow robust conclusions regarding the effects of centre‐based day care on outcomes for children younger than five years of age and their families in high‐income countries.

Potential biases in the review process

We used a comprehensive search strategy to minimise the potential impact of publication bias on the review process. We also searched for grey literature, but there may be unpublished studies that we did not identify.

Differences between this review and previous reviews reflect stringent inclusion criteria devised to isolate the effects of centre‐based day care. Only one study met these criteria. Studies of centre‐based day care often include other early childhood interventions, and most studies did not involve the use of randomisation. Had we employed more flexible inclusion criteria (e.g. including study designs beyond RCTs or interventions beyond centre‐based day care), our review would likely have included a much larger set of primary studies (see Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews), which would have resulted in different conclusions.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

The present review was conducted in tandem with a review of day care in low‐ and middle‐income countries (Brown 2014); this concurrent review included one study that provides inconclusive evidence regarding the effects of centre‐based day care for children younger than five years of age and their families in low‐ and middle‐income countries. Over the past 25 years, several high‐profile narrative reviews were conducted (e,g, Belsky 1988; Melhuish 2004; Burger 2010) and several meta‐analyses (e.g. Zoritch 2000; Gorey 2001; Camilli 2010) have examined whether the experience of day care in early childhood is related to positive or negative outcomes. The conclusions of previous reviews differ from those drawn on the basis of results reported in the current review. Most notably, previous reviews have included evaluations of day care with additional intervention components, as well as studies employing quasi‐experimental designs, thus encompassing a greater number of studies than were identified for the current review. Our review has identified no randomised controlled trials that demonstrate effects of day care on child and family outcomes.

One review of 32 experimental and quasi‐experimental studies concluded that most included programs had considerable short‐term effects and smaller long‐term effects on children's cognitive development (Burger 2010). Another narrative review that did not specify any criteria for including studies concluded that provision of preschool programmes for children at age three or older is beneficial for their educational and social development, and that these effects may be mediated by the quality of services and the socioeconomic situation (Melhuish 2004). A third narrative review argues that day care may be associated with insecure attachment (Belsky 1988).

A meta‐analysis of 161 studies of centre‐based early childhood programmes reported moderate positive effects of centre‐based early interventions on children's cognitive ability, attainment of educational goals and socioemotional development (Camilli 2010). Another meta‐analysis of 35 studies found strong positive effects of day care on cognitive ability that were not sustained, but the review also reported benefits for attainment of educational goals (Gorey 2001).

A previous Cochrane review included eight studies, of which seven were randomised controlled trials (Zoritch 2000). It identified positive effects on child and maternal outcomes, but all of these studies were excluded from our review because the interventions were not limited to centre‐based day care, or because the study was not a randomised controlled trial.

This systematic review included only randomised controlled trials of centre‐based day care without additional components that are not centre‐based or do not target children. Only one study met these criteria and was included. This demonstrates that current evidence on the effects of day care as a stand‐alone intervention is scarce.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

There is great demand for centre‐based day care services in high‐income countries, with approximately 80% of children regularly attending day care centres on a full‐time or part‐time basis. This review found only one randomised controlled trial that assessed the benefits or harms of centre‐based day care as a sole intervention for children younger than five years of age and their families in high‐income countries. This limits the possibility of providing robust guidance for parents, policymakers and other stakeholders regarding its effects. However, the demand for day care is likely to be determined by factors other than research evidence, and sufficient provision of high‐quality services may be necessary to allow parents to participate in the labour force (Gelbach 2002; Esping‐Andersen 2009).

Evidence from systematic reviews that include study designs beyond randomised studies and assess day care as an isolated intervention (i.e. without significant co‐interventions) may offer some guidance for those concerned. However, high‐quality evidence on this widely available service is lacking, and advice for future research is provided in the next section.

Implications for research.

Centre‐based day care is a highly complex area of research, with many studies necessarily examining a vast array of interventions, including many that go beyond simple centre‐based care. Rigorous evidence is urgently needed on the effectiveness of centre‐based day care alone on a host of child and family outcomes, including child cognitive and psychosocial outcomes in the short and long term, and maternal employment. Because of the widespread use of day care services, and because children require some form of care, it may be impossible to compare the effects of receiving day care versus not receiving it. Thus, it is important that future effectiveness trials examine the effects of clearly defined and replicable centre‐based day care versus a comparison condition (i.e. an alternative day care arrangement).

The review authors support previous recommendations that new studies should give special attention to low‐income families (Melhuish 2004). This may present a possibility for uncontaminated randomised controlled trials in the case of oversubscription to available (subsidised) day care places, as these families may be less likely to secure unsubsidised day care services not offered as part of a study. We also suggest that future researchers should explore aspects of day care centres that influence the quality and effectiveness of day care services and should investigate mechanisms of effect.

Notes

The review authors are publishing another related review: Brown TW, Van Urk FC, Waller R, Mayo‐Wilson E. Centre‐based day care for children younger than five years of age in low‐ and middle‐income countries. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, in press.

Acknowledgements

This review was produced within the Cochrane Developmental, Psychosocial and Learning Problems Group.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Search strategies

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (2014, Issue 4)—281 records—searched on 24 April 2014

(http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/cochranelibrary/search/)

Searched in trials:

1. child* or infant* or boys or girls or toddler* or pre‐kindergarten or prekindergarten or "pre kindergarten" or baby or babies in abstract

2. daycare or day‐care or "day care" or creche or nursery or (early NEAR/2 intervention) or (child* NEAR/2 center*) or (child* NEAR/2 centre*) or "childcare center*" or "childcare centre*" in title

3. #1 and #2

MEDLINE (Ovid)—9343 records—last searched 24 April 2014

We used the following search strategy in Ovid MEDLINE and adapted it for other databases using appropriate controlled vocabulary and syntax. This strategy includes the Cochrane recommended filter for identifying randomised trials (Lefebvre 2011).

1. child day care centers/ 2. Schools, Nursery/ 3. "Early Intervention (Education)"/ 4. ((early adj2 education$) or ECCE).tw. 5. (creche$ or nurser$ or kindergarten$ or kinder‐garten$ or preschool$ or pre‐primary or preprimary or playgroup$ or play‐group$ or pre‐school$ or (child$ adj3 centre$) or (child$ adj3 center$)).tw. (32921) 6. or/1‐5 7. child care/ or child care.tw. 8. (centre$ or center$ or facilit$ or "out of home" or polic$ or program$ or scheme$).tw. 9. 7 and 8 10. exp child/ 11. exp Infant/ 12. (infant$ or baby or babies or toddler$ or child$ or boy$ or girl$ or kid$ or pre‐kindergarten$ or prekindergarten$ or preschool$ or pre‐school$).tw. 13. or/10‐12 14. Day Care/ 15. daycare$ or day‐care$ or daycentre$ or daycenter$ or (centre‐based adj3 care$) or (center‐based adj3 care$) or (day$ adj3 (centre$ or center$))).tw. 16. 14 or 15 17. 13 and 16 18. 6 or 9 or 17 19. randomized controlled trial.pt. 20. controlled clinical trial.pt. 21. randomi#ed.ab. 22. placebo$.ab. 23. randomly.ab. 24. trial.ab. 25. groups.ab. 26. or/19‐25 27. exp animals/ not humans.sh. 28. 26 not 27 29. 18 and 28

EMBASE (Ovid)—1062 records—last searched 24 April 2014

1. child day care centers/ 2. Schools, Nursery/ 3. "Early Intervention (Education)"/ 4. ((early adj2 education$) or ECCE).tw. 5. (creche$ or nurser$ or kindergarten$ or kinder‐garten$ or preschool$ or pre‐primary or preprimary or playgroup$ or play‐group$ or pre‐school$ or (child$ adj3 centre$) or (child$ adj3 center$)).tw. 6. or/1‐5 7. child care/ or child care.tw. 8. (centre$ or center$ or facilit$ or "out of home" or polic$ or program$ or scheme$).tw. 9. 7 and 8 10. exp child/ 11. exp Infant/ 12. (infant$ or baby or babies or toddler$ or child$ or boy$ or girl$ or kid$ or pre‐kindergarten$ or prekindergarten$ or preschool$ or pre‐school$).tw. 13. or/10‐12 14. Day Care/ 15. daycare$ or day‐care$ or daycentre$ or daycenter$ or (centre‐based adj3 care$) or (center‐based adj3 care$) or (day$ adj3 (centre$ or center$))).tw. 16. 14 or 15 17. 13 and 16 18. 6 or 9 or 17 19. randomized controlled trial.pt. 20. controlled clinical trial.pt. 21. randomi#ed.ab. 22. placebo$.ab. 23. randomly.ab. 24. trial.ab. 25. groups.ab. 26. or/19‐25 27. exp animals/ not humans.sh. 28. 26 not 27 29. 18 and 28

Social Sciences Citation Index—2831 records—last searched 24 April 2014

1. Title= child* or infant* or boys or girls or toddler* or pre‐kindergarten or prekindergarten or "pre kindergarten" or baby or babies

2. Title= daycare or day‐care or “day care” or creche or nursery or (early NEAR/2 intervention) or (child* NEAR/2 center*) or (child* NEAR/2 centre*) or "childcare center*" or "childcare centre*"

3. #1 and #2

PsycINFO (Ovid)—9218 records—last searched 24 April 2014

1. ((early adj2 education$) or ECCE).tw. 2. (creche$ or nurser$ or kindergarten$ or kinder‐garten$ or preschool$ or pre‐primary or preprimary or playgroup$ or play‐group$ or pre‐school$ or (child$ adj3 centre$) or (child$ adj3 center$)).tw. 3. or/1‐2 4. child care/ or child care.tw. 5. (centre$ or center$ or facilit$ or "out of home" or polic$ or program$ or scheme$).tw. 6. 4 and 5 7. (infant$ or baby or babies or toddler$ or child$ or boy$ or girl$ or kid$ or pre‐kindergarten$ or prekindergarten$ or preschool$ or pre‐school$).tw. 8. daycare$ or day‐care$ or daycentre$ or daycenter$ or (centre‐based adj3 care$) or (center‐based adj3 care$) or (day$ adj3 (centre$ or center$))).tw. 9. 7 and 8 10. 3 or 6 or 9 11. randomized controlled trial.pt. 12. controlled clinical trial.pt. 13. randomi#ed.ab. 14. placebo$.ab. 15. randomly.ab. 16. trial.ab. 17. groups.ab. 18. or/11‐17 19. exp animals/ not humans.sh. 20. 18 not 19 21. 10 and 20

ERIC—1041 records—last searched 24 April 2014

1. Title:child* or Title:infant* or Title:boys or Title:girls or Title:toddler* or Title:pre‐kindergarten or Title:prekindergarten or Title:"pre kindergarten" or Title:baby or Title:babies

2. Title:daycare or Title:day‐care or (Title:day and Title:care) or Title:creche or Title:nursery or (Title:early and Title:NEAR/2 and Title:intervention) or (Title:child* and Title:NEAR/2 and Title:center*) or (Title:child* and Title:NEAR/2 and Title:centre*) or Title:"childcare center*" or Title:"childcare centre*"

3. #1 and #2

Conference Proceedings Citations Index–Social Sciences & Humanities (Web of Science)—132 records—last searched 24 April 2014

1. Title= child* or infant* or boys or girls or toddler* or pre‐kindergarten or prekindergarten or "pre kindergarten" or baby or babies

2. Title= daycare or day‐care or “day care” or creche or nursery or (early NEAR/2 intervention) or (child* NEAR/2 center*) or (child* NEAR/2 centre*) or "childcare center*" or "childcare centre*"

3. #1 and #2

Global Health Library (Ovid)—3978 records—last searched 24 April 2014

1. ((early adj2 education$) or ECCE).tw. 2. (creche$ or nurser$ or kindergarten$ or kinder‐garten$ or preschool$ or pre‐primary or preprimary or playgroup$ or play‐group$ or pre‐school$ or (child$ adj3 centre$) or (child$ adj3 center$)).tw. 3. or/1‐2 4. child care/ or child care.tw. 5. (centre$ or center$ or facilit$ or "out of home" or polic$ or program$ or scheme$).tw. 6. 4 and 5 7. (infant$ or baby or babies or toddler$ or child$ or boy$ or girl$ or kid$ or pre‐kindergarten$ or prekindergarten$ or preschool$ or pre‐school$).tw. 8. daycare$ or day‐care$ or daycentre$ or daycenter$ or (centre‐based adj3 care$) or (center‐based adj3 care$) or (day$ adj3 (centre$ or center$))).tw. 9. 7 and 8 10. 3 or 6 or 9 11. randomized controlled trial.pt. 12. controlled clinical trial.pt. 13. randomi#ed.ab. 14. placebo$.ab. 15. randomly.ab. 16. trial.ab. 17. groups.ab. 18. or/11‐17 19. exp animals/ not humans.sh. 20. 18 not 19 21. 10 and 20

SCOPUS—3723 records—last searched 24 April 2014

1. TITLE(daycare or day‐care or "day care" or creche OR nurser* or "early intervention*" or "child care center*" or "child care centre*" or "childcare center*" or "childcare centre*")

2. TITLE(child* or infant* or boys or girls or toddler* or pre‐kindergarten or prekindergarten or "pre kindergarten" or baby or babies)

3. #1 and #2

ZETOC—957 records—last searched 24 April 2014

1. Daycare

2. Day‐care

3. "Day care"

4. "Early Intervention"

5. #1 or #2 or #3 or #4

PQTD Open—415 records—last searched 24 April 2014

(http://pqdtopen.proquest.com/search.html)

1. Ti(daycare or day‐care or "day care" or creche or nurser* or "early intervention*" or "child care center*" or "child care centre*" or "childcare center*" or "childcare centre*")

2. Ti(child* or infant* or boys or girls or toddler* or pre‐kindergarten or prekindergarten or "pre kindergarten" or baby or babies)

3. #1 and #2

POPLINE—1559 records—last searched 25 April 2014

1. Title (daycare or day‐care or “day care” or creche or nurser* or "early intervention*" or "child care center*" or "child care centre*" or "childcare center*" or "childcare centre*")

2. Title (child* or infant* or boys or girls or toddler* or pre‐kindergarten or prekindergarten or "pre kindergarten" or baby or babies)

3. #1 AND #2

OpenGrey—361 records—last searched 24 April 2014

(child* or infant* or boys or girls or toddler* or pre‐kindergarten or prekindergarten or "pre kindergarten" or baby or babies) AND (daycare or day‐care or “day care” or creche or nursery or (early NEAR/2 intervention) or (child* NEAR/2 center*) or (child* NEAR/2 centre*) or "childcare center*" or "childcare centre*")

Clinical Trials.gov—1934 records—last searched 24 April 2014

(daycare or day‐care or “day care” or creche or nurser* or "early intervention*" or "child care center*" or "child care centre*" or "childcare center*" or "childcare centre*") AND (child* or infant* or boys or girls or toddler* or baby or babies)

International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (limited to Clinical Trials in Children)—18 records—last searched 24 April 2014

(http://apps.who.int/trialsearch/)

Title (daycare or day‐care or “day care” or creche or nursery or (early NEAR/2 intervention) or (child* NEAR/2 center*) or (child* NEAR/2 centre*) or "childcare center*" or "childcare centre*")

Appendix 2. Analytical methods from protocol for use in future updates

| Measures of treatment effect | Studies often report outcomes using multiple definitions and outcome measures. We will give preference to data that involved the least manipulation by study authors or inference by review authors; that is, we will extract raw values (e.g. means, standard deviations) rather than calculated effect sizes (e.g. Cohen’s d). If outcomes are reported as final values and as changes from baseline, we will extract the final values For studies with multiple time points, we will include the time point that occurred the greatest number of days after randomisation. If possible, we will also conduct an analysis of prespecified time points: up to 25 months, 25 months or more We will calculate risk ratios (RRs) and 95% confidence intervals for dichotomous outcomes. When risk ratios or rate ratios cannot be calculated (when total sample size is unknown), we will calculate odds ratios (ORs). If we cannot calculate RRs for all studies included in an analysis but can calculate ORs for all studies, we will report ORs for all studies included in that analysis. We will not combine RRs and ORs together in a meta‐analysis (see Data synthesis). We will give preference to denominators in the following order: events per person year, events per person with definite outcome known (or imputed, as described in Dealing with missing data), events per person randomly assigned We will use Hedges’ (adjusted) g (a standardised mean difference) for each outcome for which continuous data are provided |

| Unit of analysis issues | Some data in future updates of this review may come from cluster‐randomised trials, which randomly assign groups of people rather than individuals. For each cluster‐randomised trial, we will first determine whether or not the data incorporate sufficient controls for clustering (such as robust standard errors or hierarchical linear models). If the data do not have proper controls, we will attempt to obtain an appropriate estimate of the intracluster correlation coefficient (ICC). If we cannot find an estimate in the report of the trial, we will request an estimate from the trial report authors. We will use the ICC estimate to control for clustering, according to procedures described in Higgins 2011 |

| Dealing with missing data | For all analyses, we will attempt to include all study participants, and we will contact study authors to request data on all participants randomly assigned for all outcomes. When analyses are reported for completers and controls for dropout are applied, we will extract the latter. If participant data are missing from a study, or if reasons for dropout are not included, we will contact the study authors for additional information. For studies with dichotomous data, if no information can be gathered from study authors, we will assume that participants in all groups for whom data are missing experienced negative outcomes. All missing data will be recorded on the data extraction sheet and reported in the ’Risk of bias’ tables |

| Assessment of heterogeneity | Differences among included studies are discussed in terms of study participants, interventions, outcomes and methods. For each meta‐analysis, we will visually inspect forest plots to see whether the confidence intervals of individual studies have poor overlap, conduct a Chi2 test and calculate the I2 statistic. We will consider meta‐analyses to have heterogeneity when the P value for Chi2 is less than 0.10 and I2 is greater than 25%. Because of the likelihood of variability in participants and co‐interventions across different sites, this review may include studies that are clinically heterogeneous. If studies are determined to be too clinically heterogeneous, we will not conduct a primary meta‐analysis but will discuss results narratively, including detailed descriptions of the interventions of all included studies |

| Assessment of reporting biases | For each meta‐analysis that includes 10 or more studies, we will draw a funnel plot and look for asymmetry to assess the possibility of small study or reporting bias (see Sensitivity analysis) |

| Data synthesis | The primary meta‐analysis will include all centre‐based day care programmes versus non–centre‐based child care (e.g. home care by a parent). Subgroup analysis will be conducted as detailed below in Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity. We will use Review Manager (RevMan) Version 5.1 (Review Manager 2011) to conduct all meta‐analyses. All meta‐analyses will be conducted using the random‐effects model. Risk ratios and 95% confidence intervals will be calculated for dichotomous outcomes and combined using Mantel‐Haenszel methods. When risk ratios or rate ratios are not reported and cannot be calculated (in case the exact sample size is unknown) for all studies included in a meta‐analysis, we will calculate and report odds ratios. Studies for which effect sizes are expressed as RRs and ORs will not be meta‐analysed jointly. If studies report dichotomous data in multiple formats that cannot be combined in RevMan, we will use Comprehensive Meta‐Analysis Version 2 software (Borenstein 2005) to calculate log risk ratios and standard errors for the data and enter these log risk ratios and standard errors into RevMan. |

| Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity | We will conduct the following subgroup analyses:

|

| Sensitivity analysis | Sensitivity analysis will be used as follows:

|

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Day care vs control.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Cognitive ability (as measured by GMDS) | 1 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 2 Child psychosocial development (parent‐reported) | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 3 Child psychosocial development (sensitivity analysis) | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 4 Paid maternal employment | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 5 Maternal hours per week in paid employment | 1 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 6 Household income > £200 | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 7 Paid maternal employment (sensitivity analysis) | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected | |

| 8 Household income > £200 (sensitivity analysis) | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Totals not selected |

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Day care vs control, Outcome 1 Cognitive ability (as measured by GMDS).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Day care vs control, Outcome 2 Child psychosocial development (parent‐reported).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Day care vs control, Outcome 3 Child psychosocial development (sensitivity analysis).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Day care vs control, Outcome 4 Paid maternal employment.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Day care vs control, Outcome 5 Maternal hours per week in paid employment.

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Day care vs control, Outcome 6 Household income > £200.

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Day care vs control, Outcome 7 Paid maternal employment (sensitivity analysis).

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Day care vs control, Outcome 8 Household income > £200 (sensitivity analysis).

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Toroyan 2003.

| Methods | Study design: randomised controlled trial with 2 arms (centre‐based day care vs control) Sampling: non‐probability sampling (families who had applied for a place at the centre that served as the study setting for a child between 6 months and 3.5 years of age were invited to take part) Unit of randomisation: families. For child outcomes, robust standard errors were computed that assumed that only outcome variables from different families are conditionally independent. Non‐parametric bootstrap confidence intervals were used for highly skewed continuous data Follow‐up duration: 18 months | |

| Participants | Setting: Early Years centre based in the London Borough of Hackney, United Kingdom Participants: 123 families with 147 children were recruited. Randomisation was used to allocate oversubscribed places. 120 families with 143 children were randomly assigned. 110 mothers (mean age 31.9 years) with 134 children (mean age 26.6 months) completed the baseline questionnaire. 114 mothers provided outcome data relevant for this review at follow‐up. 127 children provided outcome data relevant for this review at follow‐up | |

| Interventions | Intervention group: 51 families and 64 children received high‐quality day care for children younger than 5 years of age. The Early Years Centre at which the intervention took place employed qualified teachers, and education was integrated into care of the children. Integration of health and social services was encouraged Comparison group: preintervention and postintervention questionnaires. Control group families were expected to (and many did) use a range of child‐care services that they secured for themselves, including child care at other day care facilities | |

| Outcomes |

Outcomes relevant for this review Child outcomes

Maternal and family outcomes

Other outcomes Child outcomes

Maternal and family outcomes

|

|

| Notes | A power calculation was conducted (n = 140 families), but the study lacks statistical power because of the inability to recruit and maintain a sufficiently large sample size | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | The allocation sequence was computer generated, and minimisation was used to provide a reasonable balance on 3 potential confounders (family size, lone parenthood, application for a fee‐paying or subsidised place) |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Participants were given a unique family ID number, and an independent statistician entered these numbers into the minimisation software. ID numbers were matched with corresponding names by administrative staff at the centre, who sent letters to applicants advising them of their allocation status |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | The nature of the intervention (obvious difference between receiving day care and not receiving it) makes this form of blinding impossible |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Maternal outcomes and some child outcomes were self‐reported by mothers who were aware of their assigned condition. Children were assessed by a paediatrician who was not informed of their group status. Data entry was blind to group allocation |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | 3% of mothers in the intervention group and 5% of mothers in the control group were lost to 18‐month follow‐up. 5% of children in the intervention group and 16% of children in the control group were lost to 18‐month paediatric assessment. Information reported regarding reasons for attrition at follow‐up is insufficient |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | No prepublished trial protocol was found. All known outcomes were reported |

| Other bias | High risk | Risk of contamination bias is high. At 18‐month follow‐up, 63% of control group children were in formal centre‐based day care that their mothers had secured for themselves outside the study |

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Aunio 2005 | Assigned control condition included centre‐based day care |

| Bronson 1984 | Intervention included parent education |

| Brooks‐Gunn 1994 | Intervention included parent curricula delivered through home visiting and parent groups |

| Campbell 1994 | Intervention included an offered series of programmes for parents covering topics such as family nutrition, legal matters, behaviour management and toy making |

| Cooper 1998 | Not a randomised controlled trial or a quasi‐randomised controlled trial |

| Deutsch 1971 | Intervention included home visits for intervention purposes and parent training |

| Gallagher 2009 | Assigned control conditions included centre‐based day care |

| Garber 1973 | Intervention included parent training (preparation for employment opportunities and improvement in home‐making and child‐rearing skills) |

| Gray 1970 | Intervention included home visits for intervention purposes |

| Love 2005 | Interventions included one or more of the following: home visits, parenting education (as part of Head Start services) |

| Palmer 1983 | Not a randomised controlled trial or a quasi‐randomised controlled trial |

| Schweinhart 1986 | Intervention included educational home visits for intervention purposes. During these home visits, parent education was provided |

| Wasik 1990 | Interventions included home visits for intervention purposes. During these home visits, parent education was provided |

Differences between protocol and review

The original protocol for this review stated that review authors would deal with missing data for dichotomous outcomes by imputing data assuming that missing participants in all groups experienced negative outcomes. According to this protocol, results that included imputed data would be reported in the main analysis. A postprotocol decision was made to report effect sizes in the main analysis as reported in original articles without imputing data for missing participants (see Effects of interventions). Sensitivity analyses were performed to compare results with and without imputation of data for missing participants (see Sensitivity analysis).

Contributions of authors

FvU and TB conducted the searches and extracted study data. All review authors contributed to drafting the review.

Sources of support

Internal sources

-

Centre for Outcomes Research and Effectiveness, Research Department of Clinical, Educational and Health Psychology, University College London, UK.

Salary

-

Centre for Evidence Based Intervention, Department of Social Policy and Intervention, University of Oxford, UK.

Salary, Graduate Stipends

-

National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health (NCCMH), UK.

Salary

External sources

No sources of support supplied

Declarations of interest

Felix C van Urk—none known. Taylor W Brown—none known. Rebecca Waller—none known. Evan Mayo‐Wilson—none known.

New

References

References to studies included in this review

Toroyan 2003 {published data only}

- Mujica Mota R, Lorgelly PK, Mugford M, Toroyan T, Oakley A, Laing G, et al. Out‐of‐home day care for families living in a disadvantaged area of London: economic evaluation alongside a RCT. Child: Care, Health & Development 2006;32(3):287‐302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toroyan T, Oakley A, Laing G, Roberts I, Mugford M, Turner J. The impact of day care on socially disadvantaged families: an example of the use of process evaluation within a randomized controlled trial. Child: Care, Health and Development 2004;30(6):691‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toroyan T, Roberts I, Oakley A, Laing G, Mugford M, Frost C. Effectiveness of out‐of‐home day care for disadvantaged families: randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2003;327:906‐10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to studies excluded from this review

Aunio 2005 {published data only}

- Aunio P, Hautamäki J, Luit JEH. Mathematical thinking intervention programmes for preschool children with normal and lower number sense. European Journal of Special Needs Education 2005;20(2):131‐46. [Google Scholar]

Bronson 1984 {published data only}

- Bronson MB, Pierson DE, Tivnan T. The effects of early education on children's competence in elementary school. Evaluation Review 1984;8(5):615‐29. [Google Scholar]

Brooks‐Gunn 1994 {published data only}

- Berlin LJ, Brooks‐Gunn J, McCarton C, McCormick MC. The effectiveness of early intervention: examining risk factors and pathways to enhanced development. Preventive Medicine 1998;27(2):238‐45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks‐Gunn J, McCormick MC, Shapiro S, Benasich AA, Black GW. The effects of early education intervention on maternal employment, public assistance, and health insurance: the infant health and development program. American Journal of Public Health 1994;84(6):924‐31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klebanov PK, Brooks‐Gunn J. Differential exposure to early childhood education services and mother‐toddler interaction. Early Childhood Research Quarterly 2008;23(2):213‐32. [Google Scholar]

- Lee K. Effects of experimental center‐based child care on developmental outcomes of young children in poverty. Social Service Review 2005;79(1):158‐80. [Google Scholar]

- Martin A, Brooks‐Gunn J, Klebanov P, Buka SL, McCormick MC. Long‐term maternal effects of early childhood intervention: findings from the Infant Health and Development Program (IHDP). Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology 2008;29(2):101‐17. [Google Scholar]

- McCormick MC, Brooks‐Gunn J, Shapiro S, Benasich AA, Black G, Gross RT. Health care use among young children in day care: results in a randomized trial of early intervention. JAMA 1991;265(17):2212‐7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Campbell 1994 {published data only}

- Campbell FA, Breitmayer B, Ramey CT. Disadvantaged single teenage mothers and their children: consequences of free educational day care. Family Relations 1986;35(1):63‐8. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell FA, Pungello EP, Miller‐Johnson S, Burchinal M, Ramey CT. The development of cognitive and academic abilities: growth curves from an early childhood educational experiment. Developmental Psychology 2001;37(2):231‐42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell FA, Ramey CT. Effects of early intervention on intellectual and academic achievement: a follow‐up study of children from low‐income families. Child Development 1994;65(2):684‐98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feagans LV, Farran DC. The effects of daycare intervention in the preschool years on the narrative skills of poverty children in kindergarten. International Journal of Behavioral Development 1994;17(3):503‐23. [Google Scholar]

- Martin SL, Ramey CT, Ramey S. The prevention of intellectual impairment in children of impoverished families: findings of a randomized trial of educational day care. American Journal of Public Health 1990;80(7):844‐7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin AE, Campbell FA, Pungello EP, Skinner M. Depressive symptoms in young adults: the influences of the early home environment and early educational child care. Child Development 2007;78(3):746‐56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pungello EP, Kainz K, Burchinal M, Wasik BH, Sparling JJ, Ramey CT, et al. Early educational intervention, early cumulative risk, and the early home environment as predictors of young adult outcomes within a high‐risk sample. Child Development 2010;81(1):410‐26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramey CT, Campbell FA, Ramey SL. Early intervention: successful pathways to improving intellectual development. Developmental Neuropsychology 1999;16(3):385‐92. [Google Scholar]

Cooper 1998 {published data only}

- Cooper M, Pettit E, Clibbens J. Evaluation of a nursery based language intervention in a socially disadvantaged area. International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders 1998;33 Suppl 1:526‐31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Deutsch 1971 {published data only}

- Deutsch M, Deutsch CP, Jordan TJ, Grallo R. The IDS Program: an experiment in early and sustained enrichment. In: The Consortium for Longitudinal Studies, editor(s). As the Twig Is Bent... Lasting Effects of Preschool Programs. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1983:377‐410. [Google Scholar]

- Deutsch M, Taleporos E, Victor J. A brief synopsis of an initial enrichment program in early childhood. A Report on Longitudinal Evaluations of Preschool Programs. Vol. 1. Washington, DC: Department of Health Education and Welfare, 1974:74‐124. [Google Scholar]

- Deutsch M, Victor J, Taleporos E, Deutsch C, Faigao B, Calhoun C, et al. An Evaluation of the Effectiveness of an Enriched Curriculum in Overcoming the Consequences of Environmental Deprivation. New York: New York University, Institute of Developmental Studies, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Jordan TJ, Grallo R, Deutsch M, Deutsch CP. Long‐term effects of early enrichment: a 20‐year perspective on persistence and change. American Journal of Community Psychology 1985;13(4):393‐415. [Google Scholar]

Gallagher 2009 {published data only}

- Gallagher AL, Chiat S. Evaluation of speech and language therapy interventions for pre‐school children with specific language impairment: a comparison of outcomes following a specialist intensive, nursery‐based and no intervention. International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders 2009;44(5):616‐38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Garber 1973 {published data only}

- Garber H, Heber R. The Milwaukee Project: Early intervention as a Technique to Prevent Mental Retardation. Storrs, CT: The University of Connecticut National Leadership Institute, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Garber HL. The Milwaukee Project: Preventing Mental Retardation in Children at Risk. Washington, DC: American Association on Mental Retardation, 1988. [Google Scholar]

Gray 1970 {published data only}

- Gray SW, Klaus RA. The Early Training Project: a seventh‐year report. Child Development 1970;41(4):909‐24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray SW, Ramsey BK, Klaus RA. From Three to Twenty: The Early Training Project in Longitudinal Perspective. Baltimore: University Park, 1981. [Google Scholar]

Love 2005 {published data only}

- Love JM, Kisker E, Ross C, Raikes H, Constantine J, Boller K, et al. The effectiveness of early head start for 3‐year‐old children and their parents: lessons for policy and programs. Developmental Psychology 2005;41(6):885‐901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Palmer 1983 {published data only}

- Lazar I, Darlington R, Murray H, Royce J, Snipper A, Ramey CT. Lasting effects of early education: a report from the Consortium for Longitudinal Studies. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development 1982;47(2‐3):1‐151. [Google Scholar]