Abstract

Vitamin D is linked to a number of adverse pregnancy outcomes through largely unknown mechanisms. This study was conducted to examine the role of vitamin D status in metabolomic profiles in a group of 30 pregnant, African American adolescents (17.1 ± 1.1 years) at midgestation (26.8 ± 2.8 weeks), in 15 adolescents with 25-hydroxy vitamin D (25(OH)D) ≥20 ng/mL, and in 15 teens with 25(OH)D <20 ng/mL. Serum metabolomic profiles were examined using gas chromatography–mass spectrometry and liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry. A novel hierarchical mixture model was used to evaluate differences in metabolite profiles between low and high groups. A total of 326 compounds were identified and included in subsequent statistical analyses. Eleven metabolites had significantly different means between the 2 vitamin D groups, after correcting for multiple hypothesis testing: pyridoxate, bilirubin, xylose, and cholate were higher, and leukotrienes, 1,2-propanediol, azelate, undecanedioate, sebacate, inflammation associated complement component 3 peptide (HWESASXX), and piperine were lower in serum from adolescents with 25(OH)D ≥20 ng/mL. Lower maternal vitamin D status at midgestation impacted serum metabolic profiles in pregnant adolescents.

Keywords: adolescent, pregnancy, vitamin D, biomarker, metabolomics

Introduction

Vitamin D deficiency and insufficiency are common in pregnancy. An estimated 21% to 50% of pregnant women are vitamin D inadequate (25-hydroxy vitamin D [25(OH)D] <20 ng/mL),1,2 and many pregnant women have 25(OH)D concentrations below 30 ng/mL.3–5 The prevalence of suboptimal vitamin D status in pregnant women is high and ranges from 5% to 84% globally.6–14 In a previous analysis of adolescents participating in this research study, 50% had 25(OH)D concentrations ≤20 ng/mL in pregnancy,8 and low 25(OH)D concentrations were associated with deficits in fetal femur and humerus length.15

Vitamin D is essential for optimal calcium homeostasis, immune function, and growth and development. In pregnancy, vitamin D is required for development of the fetoplacental unit, fetal growth, and regulation of placental function.16 Vitamin D is critical in the development of the fetal immune system.17 The high prevalence of vitamin D insufficiency in pregnant women is of concern, given its association with adverse perinatal outcomes.18–28 Observational studies have linked low maternal vitamin D status with an increased risk of health outcomes for the mother, fetus, and infant,18–28 including preterm birth,29 preeclampsia,22–25 infection,7,30,31 gestational diabetes, and obstructed labor.27,28 Prenatal vitamin D intake or supplementation has been associated with higher infant birth weight,27,28,32,33 head and arm circumference, and skinfold thickness.32,33 A recent randomized controlled trial has suggested that vitamin D supplementation (400, 2000, or 4000 IU daily) during pregnancy is safe and effective34 and can reduce the risk of maternal comorbidities during pregnancy.35 Conversely, maternal vitamin D deficiency has been linked to poor infant and early child health, including stunting and underweight,36 deficits in neurocognitive development,20,21 asthma,37,38 and infectious diseases.39 Although several studies have found these associations, mechanisms responsible for the observed associations are limited. The recent Institute of Medicine (IOM) Committee set an estimated average requirement (EAR) of 400 IU for pregnant women, corresponding to a serum 25(OH)D level of at least 20 ng/mL, to meet the requirements for at least 97.5% of the population. Higher values were not consistently associated with greater benefit, and for some outcomes, U-shaped associations were observed (with risks at both low and high levels). The IOM Committee concluded that the available scientific evidence supports a key causal role of calcium and vitamin D in skeletal health and provided strong support to inform intake requirements. However, this issue remains controversial, particularly for extraskeletal outcomes, and higher intakes have been recommended by the Endocrine Society for patients who are at risk of specific diseases.40,41 Gaps in the literature that were identified by the IOM included inconsistent evidence (inconclusive regarding causality), insufficient data to inform nutritional requirements, and limited and uninformative evidence from randomized trials for extraskeletal outcomes.

Although vitamin D status has been linked to multiple processes that are integral to optimal pregnancy outcomes, to date there have been no published studies assessing the relationship of vitamin D status in pregnancy with maternal metabolomics profiles or related biomarkers. We therefore conducted this study to examine the role of vitamin D status in metabolomic profiles in midpregnancy in 30 African American adolescents, a group with increased risk of both vitamin D insufficiency and pregnancy complications.

Materials and Methods

Participants and Study Procedures

Participants in this study were enrolled in a larger longitudinal study of maternal and fetal bone health and iron status across gestation among pregnant adolescents (13-18 years). All teens were recruited from the Rochester Adolescent Maternal Program in Rochester, New York. Pregnant adolescents were eligible to participate if they were between 12 and 30 weeks of gestation at enrollment, were healthy, and carrying a single fetus. Adolescents were excluded if they had known medical complications, including HIV infection, diabetes, gestational hypertension, preeclampsia, eating disorders, malabsorption diseases, or any other diagnosed medical conditions. Written informed consent was obtained from all study participants, and the research protocol and study procedures were approved by the institutional review boards at Cornell University and the University of Rochester.

Structured interviews were conducted at the baseline clinic visit to collect information on demographic characteristics, including maternal age, educational level, socioeconomic status, and obstetric history. All adolescents were prescribed prenatal supplements containing 27 mg of iron and 400 μg of folate as part of their standard prenatal care. Supplemental vitamin D3 (400 IU/d) was provided to teens whose midgestation 25(OH)D concentrations were ≤20 ng/mL, but none of the adolescents in this metabolomic study had received vitamin D supplementation at the time that these metabolomic serum samples were collected.

Adolescents attended up to 3 study visits across pregnancy, timed to coincide with early, mid, and late gestation. At each visit, maternal anthropometric measures were recorded, and dietary intake was assessed with a 24-hour dietary recall.

Biochemical Assessment of Vitamin D Status

Maternal vitamin D status was evaluated at midgestation (26.8 ± 2.8 weeks), based on serum concentrations of 25(OH)D. Nonfasting blood samples (10 mL) were collected and allowed to clot at room temperature, and serum was separated by centrifugation, processed, and stored ≤−80°C until analyzed. An aliquot of serum was immediately sent to Quest Laboratories for assessment of 25(OH)D with the use of Diasorin RIA (Diasorin, Inc, Stillwater, Minnesota). This laboratory participates in the vitamin D External Quality Assessment Scheme as a means of quality assurance. The season of each blood collection was classified using seasonal classifications for the northeast United States.42

Vitamin D status was categorized as insufficient if 25(OH)D was <20 ng/mL or sufficient if 25(OH)D was ≥20 ng/mL, in accordance with the recent IOM guidelines.43 After a high prevalence of vitamin D insufficiency was observed in the first 37 study participants, all subsequent participants found to be vitamin D insufficient at midgestation were provided with an additional 400 IU vitamin D3 at their next prenatal visit and were instructed to take 1 pill daily over the remainder of gestation. Detailed data on vitamin D metabolism, including 25(OH)D, parathyroid hormone, 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D, serum total calcitriol, vitamin D receptor, placental cytochrome P (CYP) 27B1 and CYP24A1, interleukin-6 (IL-6), leptin, and osteoprotegerin, have been previously published.8,15,44–48

Laboratory Investigations

In 2012, additional metabolomic analyses were conducted on stored plasma specimens. Midgestation (26.8 ± 2.8 weeks) serum samples were randomly selected from African American participants to obtain equal number of those with high 25(OH)D (≥20 ng/mL; n = 15, 28.3 ± 4.7 ng/mL) or low 25(OH)D (<20 ng/mL; n = 15, 10.4 ± 2.0 ng/mL), while matching patients between groups for the gestational age at the time of blood sampling. Sera were sent on dry ice to Metabolon, Inc (Durham, North Carolina) for analysis.

Upon receipt, the samples were extracted, split into equal parts, and prepared for analysis using Metabolon’s standard solvent extraction method. Global biochemical profiles were determined using gas chromatography–mass spectrometry and liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry. Several technical replicate samples were created from a homogeneous pool containing a small amount of all study samples. Instrument variability was determined by calculating the median relative standard deviation (RSD) for the internal standards that were added to each sample prior to injection into the mass spectrometers. Overall process variability was determined by calculating the median RSD for all endogenous metabolites (ie, noninstrument standards), which are technical replicates of pooled samples. A total of 326 compounds were identified and included in subsequent statistical analyses.

Statistical Analyses

Differences in the metabolite profile between low and high vitamin D groups were analyzed using a recently described novel hierarchical mixture model,49 in which differential mean and variance were considered random effects. After log-transforming and median centering the data, the Harvest model was used to simultaneously test for differential mean and variance between the groups. In order to adjust for multiple hypothesis testing (since 326 metabolites were tested), significance was determined after applying the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure.

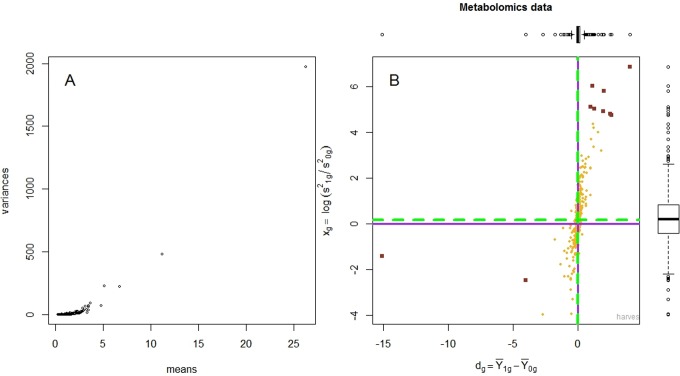

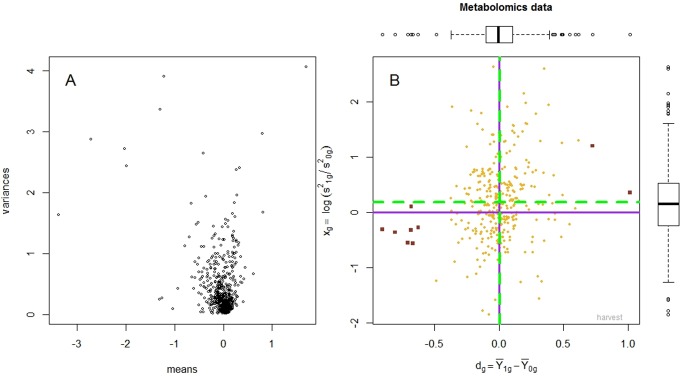

The mean and variance of the metabolites (raw and log-transformed data) are presented in Figures 1 and 2. The hierarchical mixture model assumes that the biochemical concentrations are normally distributed and, in particular, that the mean and variance of the normal distribution are not correlated. However, data provided by Metabolon appeared to violate this condition (Figure 1A), as the variance increased exponentially with the mean. Therefore, we applied a variance stabilizing transformation to the data, by taking the logarithm; to remove any patient-specific effect, medians of all profiles were equalized and a diagnostic plot was obtained (Figure 2A). This log transformation was critical, as after transformation, the mean and the variance were no longer correlated (Figure 2A). In Figure 2B, the Harvest plot summarizes the difference between the means evident in the high and low vitamin D groups plotted along the horizontal axis and the logarithm of the ratio between the variances as shown in the vertical axis. The Harvest model was used to simultaneously test for differential mean and variance.

Figure 1.

This figure depicts the mean and variance of the metabolites in the raw data (prior to transformation and median equalization). The mean and the variance are highly correlated (Panel A). There is a clear trend—that is, the variance increases exponentially with the mean—which necessitates data transformation. Panel B displays the Harvest plot: the difference between the means, between high and low 25(OH)D groups, is plotted along the horizontal axis, and the ratio between the variances is plotted along the vertical axis.

Figure 2.

This figure depicts the mean and variance of metabolites after applying a variance stabilizing transformation to the data (by taking the logarithm) and equalizing the medians of all 30 profiles. The mean and the variance are no longer correlated (Panel A). The Harvest plot is presented in Panel B: the difference between the means (between high and low serum vitamin D groups) is plotted along the horizontal axis, and the logarithm of the ratio between the variances is plotted along the vertical axis. The 11 metabolites with significantly different means are depicted as dark red squares.

Of note is that conducting the analysis using a 1 metabolite at a time approach (ie, with t tests, as in the initial analysis provided), there were no discoveries at the 0.05 false discovery rate level. However, the hierarchical mixture model used in this analysis increased the power to detect differential metabolites by (1) accounting for the differential variation and (2) “borrowing” strength across all metabolites, by modeling the mean and variance of the data as random effects.

Vitamin D status was categorized as insufficient if 25(OH)D was <20 ng/mL or sufficient if 25(OH)D was ≥20 ng/mL, in accordance with the recent IOM guidelines,43 requirements for optimal calcium homeostasis,50,51 and to be consistent with definitions used in published data from the larger cohort of adolescents.8,15 We also conducted analyses using quintiles based on the distribution of vitamin D concentrations in this population, comparing the highest (25(OH)D ≥32 ng/mL) to the lowest (≤10 ng/mL) quintiles.

We also explored potential nonlinearity of the relationships between covariates and outcomes nonparametrically, using stepwise restricted cubic splines,52,53 and used the likelihood ratio test to compare the model with only the linear term to the model with the linear and the cubic spline terms. If nonlinear associations are not reported, they were not significant. The approach proposed by Rothman and Greenland was used to control for confounding, in which all known or suspected risk factors for the outcome which lead to a greater than 10% change-in-estimate were included in the models.54 Observations with missing data for covariates were retained in the analysis using the multiple imputation method. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS software version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Inc, Cary, North Carolina), R version 3.1.0 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria), and the Harvest application in R.49

Results

The characteristics of the participants included in these analyses are presented in Table 1. A total of 326 compounds were identified in metabolomic analyses and included in subsequent statistical analyses. A total of 16 metabolites were significantly different (P < .20; Table 2) between the high and low vitamin D groups after correcting for multiple hypothesis testing; and 11 of these 16 metabolites remained significantly different (P < .05), after correcting for multiple hypothesis testing. There were no significant differences in variances of metabolites between vitamin D groups (Figure 2B). Findings from quintile analyses were similar and are presented in Table 3.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Enrolled Pregnant Adolescents.a

| Maternal Characteristics | Total Cohort | Low Vitamin D | Adequate Vitamin D | P Valueb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total participants recruited, n | 168 | 15 | 15 | |

| Age at enrollment, y | 17.1 ± 1.1 | 17.1 ± 1.4 | 16.9 ± 1.2 | .647 |

| African American, % (n) | 66.1 (111) | 100.0 (15) | 100.0 (15) | – |

| Parity ≥1, % (n) | 9.2 (16) | 20.0 (3) | 20.0 (3) | .999 |

| Smoking at enrollment, % (n) | 10.1 (17) | 0.0 (0) | 13.3 (2) | .483 |

| Prepregnancy BMI, kg/m2 | 24.7 ± 5.3 | 24.0 ± 5.0 | 21.8 ± 4.0 | .202 |

| Dietary vitamin D intake, μg/d | 5.4 ± 3.4 | 4.0 ± 3.2 | 5.5 ± 3.4 | .228 |

| Dietary calcium intake, mg/d | 913.0 ± 414.0 | 742.3 ± 358.4 | 927.4 ± 341.6 | .167 |

| Gestational age at sample | 26.3 ± 3.6 | 26.8 ± 2.8 | 26.8 ± 2.9 | .993 |

| 25(OH)D, ng/mL | 22.1 ± 10.2 | 10.4 ± 2.0 | 28.3 ± 4.7 | <.0001 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; SD, standard deviation; 25(OH)D, 25-hydroxy vitamin D.

aValues presented are mean ± SD unless otherwise noted.

bThe boldface indicates values that are statistically significant P < 0.05.

Table 2.

Difference in Means and Variance of Metabolites (P < .20).

| Biochemical | Super Pathway | Subpathway | Means | Variance | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Difference | P Value | P Valuea, b | Difference | P Value | P Valuea | |||

| Xylose | Carbohydrate | Nucleotide sugars, pentose metabolism | 0.6171 | .0005 | .0151 | 1.2941 | .2467 | .9962 |

| Pyruvate | Glycolysis, gluconeogenesis, pyruvate metabolism | 0.48159 | .00638 | .1301 | −0.4439 | .5142 | .9962 | |

| Bilirubin (E,E)a | Cofactors and vitamins | Hemoglobin and porphyrin metabolism | 0.5926 | .0008 | .0229 | 0.0709 | .9077 | .9962 |

| Bilirubin (Z,Z) | 0.49380 | .00515 | .1202 | 0.3061 | .8973 | .9962 | ||

| Pyridoxate | Vitamin B6 metabolism | 1.0136 | <.00001 | <.00001 | 0.3595 | .8534 | .9962 | |

| Cholate | Lipid | Bile acid metabolism | 0.7257 | <.0001 | .0031 | 1.2004 | .2888 | .9962 |

| Taurocholenate sulfatea | 0.48989 | .00553 | .1202 | 1.2512 | .2654 | .9962 | ||

| Leukotriene B4 | Eicosanoid | −0.6659 | .0001 | .0051 | −0.5636 | .4372 | .9962 | |

| Azelate (nonanedioate) | Fatty acid, dicarboxylate | −0.9025 | <.00001 | <.0001 | −0.3119 | .6067 | .9962 | |

| Undecanedioate | −0.8040 | <.00001 | .0004 | −0.3609 | .5716 | .9962 | ||

| Sebacate (decanedioate) | −0.6831 | <.0001 | .0042 | −0.3241 | .5979 | .9962 | ||

| 1,2-Propanediol | Ketone bodies | −0.6798 | <.0001 | .0042 | 0.1079 | .9383 | .9962 | |

| Xanthine | Nucleotide | Purine metabolism, (hypo)xanthine/inosine containing | 0.54492 | .00200 | .0545 | −0.2206 | .6748 | .9962 |

| HWESASXXa | Peptide | Polypeptide | −0.6257 | .0003 | .0113 | −0.2708 | .6370 | .9962 |

| HXGXAa | −0.48309 | .00529 | .1202 | −1.2380 | .1390 | .9962 | ||

| Piperine | Xenobiotics | Food component/plant | −0.7068 | <.0001 | .0031 | −0.5484 | .4466 | .9962 |

Abbreviations: HWESASXX, inflammation associated complement component 3 peptide; HXGXA, peptide where X is equal to either isoleucine or leucine that can't be distinguished with this method.

a P value adjusted for multiple hypothesis testing by applying the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure.

bThe boldface indicates values that are statistically significant P < 0.05.

Table 3.

Difference in Means and Variance of Metabolite Quintiles (Q1 vs Q5; P < .20).

| Biochemical | Super Pathway | Subpathway | Means | Variance | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Difference | P Value | P Valuea,b | Difference | P Value | P Valuea | |||

| 3-Methyl-2-oxobutyrate | Amino acid | Valine, leucine, and isoleucine metabolism | 0.9590 | .0284 | .0220 | −3.1100 | .9988 | .9988 |

| Pyruvate | Carbohydrate | Glycolysis, gluconeogenesis, pyruvate metabolism | 1.2748 | .0017 | .0038 | −1.7292 | .9988 | .9988 |

| Xylose | Nucleotide sugars, pentose metabolism | 1.5082 | <.0001 | .0003 | 0.5623 | .9988 | .9988 | |

| Bilirubin (E,E)a | Cofactors and vitamins | Hemoglobin and porphyrin metabolism | 1.1617 | .0028 | .0123 | −0.5551 | .9988 | .9988 |

| Bilirubin (Z,Z) | 1.1644 | .0028 | .0123 | −0.2314 | .9988 | .9988 | ||

| Heme | 1.1941 | .0028 | .0105 | −0.5341 | .9988 | .9988 | ||

| Pyridoxate | Vitamin B6 metabolism | 1.5623 | <.0001 | .0002 | 1.3675 | .9988 | .9988 | |

| N1-Methyl-2-pyridone-5-carboxamide | Nicotinate and nicotinamide metabolism | 1.0021 | .0183 | .0657 | 0.6282 | .9988 | .9988 | |

| Leukotriene B4 | Lipid | Eicosanoid | −2.5278 | .0755 | .0031 | −6.0251 | .9988 | .9988 |

| Isovalerate | Fatty acid metabolism | −0.8248 | .0526 | .1787 | 0.2747 | .9988 | .9988 | |

| 3-Carboxy-4-methyl-5-propyl-2-furanpropanoate (CMPF) | Fatty acid, dicarboxylate | 0.9303 | .0298 | .1078 | 0.5736 | .9988 | .9988 | |

| Azelate (nonanedioate) | −0.8332 | .0502 | .1708 | 0.2149 | .9988 | .9988 | ||

| 13-HODE + 9-HODE | Fatty acid, monohydroxy | −0.7511 | .0878 | .1010 | −2.9410 | .9988 | .9988 | |

| 4-Hydroxybutyrate (GHB) | 0.7350 | .1467 | .1051 | 3.6311 | .9988 | .9988 | ||

| 3-Hydroxybutyrate (BHBA) | Ketone bodies | −0.8920 | .0298 | .1051 | −0.6617 | .9988 | .9988 | |

| 1-Palmitoylglycerophosphate | Lysolipid | −1.1439 | .0028 | .0049 | −2.6784 | .9988 | .9988 | |

| 1-Oleoylglycerol (1-monoolein) | Monoacylglycerol | −0.8832 | .0298 | .1084 | −0.0876 | .9988 | .9988 | |

| Pregnanediol-3-glucuronide | Sterol/Steroid | −0.5847 | .2724 | .1670 | 3.8348 | .9988 | .9988 | |

| 5α-pregnan-3β,20α-diol disulfate | −0.9634 | .0183 | .0413 | 2.0663 | .9988 | .9988 | ||

| Leucylalanine | Peptide | Dipeptide | −0.8952 | .0299 | .1051 | 0.0136 | .9988 | .9988 |

| Leucylglycine | −1.1845 | .0022 | .0083 | 0.0899 | .9988 | .9988 | ||

| Leucylleucine | −1.1250 | .0028 | .0123 | −0.6956 | .9988 | .9988 | ||

| HWESASXXa | Polypeptide | −1.0630 | .0055 | .0221 | −0.3401 | .9988 | .9988 | |

| HXGXAa | −1.1819 | .0022 | .0073 | −1.1518 | .9988 | .9988 | ||

| Xanthine | Nucleotide | Purine metabolism, (hypo)xanthine/inosine containing | 0.9437 | .0298 | .1051 | 0.2635 | .9988 | .9988 |

| Trizma acetate | Xenobiotics | Chemical | 0.9469 | .0298 | .0468 | 2.7158 | .9988 | .9988 |

Abbreviations: HWESASXX, inflammation associated complement component 3 peptide; HXGXA, peptide where X is equal to either isoleucine or leucine that can't be distinguished with this method.

aQuintile 1 vs quintile 5; P value adjusted for multiple hypothesis testing by applying the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure.

bThe boldface indicates values that are statistically significant P < 0.05.

Among the 11 metabolites identified, vitamin D sufficiency was associated with significantly higher pyridoxate, bilirubin, xylose, and cholate, and significantly lower leukotrienes, 1,2-propanediol, azelate, undecanedioate, sebacate, inflammation associated complement component 3 peptide (HWESASXX), and piperine. These 11 metabolites clustered in pathways associated with inflammation, oxidation, fatty acid metabolism, and gut microbiome metabolism as detailed subsequently.

Inflammation and Oxidase Enzymes

The sufficient vitamin D group had significantly lower values for the eicosanoid, leukotriene B4 (adjusted P value: .0051), and higher concentrations of the antioxidant, bilirubin (adjusted P value: .0229). The vitamin D sufficient group also had significantly elevated pyridoxate (adjusted P value: <.00001), an oxidase enzyme involved in vitamin B6 metabolism and significantly lower 1,2-propanediol, a ketone body, which is oxidized to lactic acid (adjusted P value: .0042).

Fatty Acid β-Oxidation

The fatty acid dicarboxylates, azelate (nonanedioate; adjusted P value: <.0001), undecanedioate (adjusted P value: .0004), and sebacate (decanedioate; adjusted P value: .0042) were significantly lower in the vitamin D sufficient group. Higher vitamin D status was also associated with significantly higher concentrations of cholate, which is involved in feedback regulation of bile acid synthesis (adjusted P value: .0031).

Altered Gut Microbiome Metabolism

Xylose concentrations were significantly elevated in the sufficient vitamin D group (adjusted P value: .015). Xylose is associated with gut microbiome metabolism of pentose phosphate-associated biochemicals.55,56

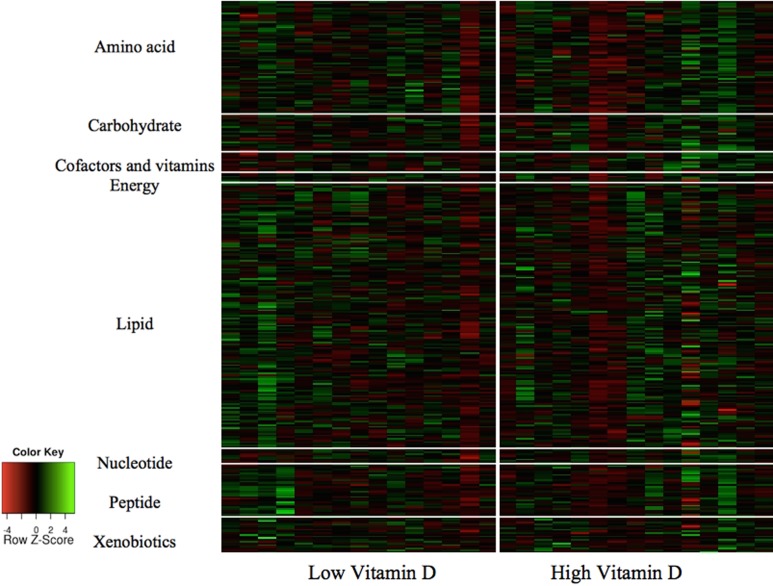

A heat map of serum metabolic profiles by vitamin D status and pathway is presented in Figure 3 which denotes significantly elevated metabolites in green and decreased metabolites in red for the 11 metabolites identified.

Figure 3.

The panels present a heat map of serum metabolic profiles by vitamin D status and pathway. Significant differences between vitamin D groups are highlighted in green (elevated) and red (decreased) and indicate differences in the 11 metabolites linked to inflammation, oxidase enzymes, fatty acid β-oxidation, and gut microbiome metabolism. (The color version of this article is available at http://rs.sagepub.com.)

Discussion

In this study, maternal vitamin D status at midgestation influenced serum metabolic profiles in pregnant adolescents. Lower maternal vitamin D status (<20 ng/mL) was associated with significantly lower pyridoxate, bilirubin, xylose, and cholate, and higher leukotriene, 1,2-propanediol, azelate, undecanedioate, sebacate, HWESASXX, and piperine. Lower maternal vitamin D status was associated with increased biochemical parameters related to inflammation, oxidative stress, fatty acid β-oxidation, and altered gut microbiome metabolism.

To our knowledge, this is the first study on the role of vitamin D status in serum metabolic profiles during pregnancy. Previous metabolomic studies have examined other biochemicals in pregnancy and the role of vitamin D in health outcomes in nonpregnant individuals. In a case–control study of 80 pregnant women, vitamin D and related metabolites (8 metabolites) were lower in women who experienced adverse pregnancy outcomes.57 In contrast, in a recent meta-analysis of 53 studies, no biomarkers (including serum vitamin D) were sufficiently accurate to predict intrauterine growth restriction.58 In nonpregnant populations, metabolomic patterns have been shown to segregate with responses to calcium and vitamin D supplementation,43 and metabolomic approaches have been utilized to identify a vitamin D responsive metabotype for markers of metabolic syndrome.59

In these pregnant adolescents, vitamin D sufficiency was associated with lower concentrations of leukotrienes and increased antioxidant and oxidase enzyme concentrations. The association between vitamin D status and a reduced inflammation has been noted in previous metabolomic studies that have identified vitamin D metabolites as potential biomarkers in inflammatory conditions, including asthma,60 ankylosing spondylitis,61 and obesity;62 and is supported by studies highlighting the anti-inflammatory effects of vitamin D.63–66

Vitamin D is known to play an extensive role in both innate and adaptive immunity,67–69 but its role in the inflammatory process during pregnancy has not been established. A previous study of vitamin D metabolic homeostasis in preeclampsia suggested that oxidative stress could alter vitamin D metabolism.26 In a recent analysis of maternal vitamin D status and inflammation across adolescent pregnancy from the same cohort (n = 168), Akoh et al found that maternal vitamin D status was correlated with tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) and C-reactive protein (CRP); analyses are ongoing to measure inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, IL-10, TNF-α, CRP) in archived maternal and cord serum (Unpublished results). These results suggest that maternal vitamin D status may influence inflammatory activity in pregnant adolescents and their infants.

Serum fatty acid dicarboxylates were significantly lower in the sufficient vitamin D group in this study, which may be associated with enhanced fatty acid β-oxidation. These findings are consistent with previous animal studies that observed a preventive effect of vitamin D on fatty acid β-oxidation.70–74 Vitamin D3 supplementation has also been found to attenuate high-fat diet-induced hepatic steatosis, via inhibition of hepatic lipogenesis and promotion of fatty acid β-oxidation in rats.70 The association between higher vitamin D status and increased fatty acid β-oxidation has been noted by in vitro findings in human cultured adipocytes where 1,25(OH)2D (and parathyroid hormone [PTH]) increased intracellular calcium and fatty acid synthase regulation and inhibited lipolysis.74 Targeted vitamin D receptor (VDR) expression in murine adipocytes also has been found to alter fatty acid β-oxidation and lipolysis.72

Elevated xylose concentrations in midgestation serum were associated with higher vitamin D status, suggestive of alterations in gut microbiome metabolism. Xylose is produced by bacterial metabolism of pentose phosphate-associated biochemicals,55,56 and alterations in this metabolite could indicate differences in the gut microbiome between the 2 vitamin D status groups. There is emerging evidence linking vitamin D status to alterations in the gut microbiota,75 gut homeostasis, and microbe–host signaling.76 Host vitamin D status may modify intestinal microbiota via T regulatory and dendritic cell development and function.77,78 In animal studies, VDR knockout mice have chronic, low-grade gastrointestinal inflammation, impaired T-cell function, and increased inflammatory responses to nonpathogenic bacterial flora in the gastrointestinal tract.79 Intestinal VDR has also been found to be involved in suppression of nuclear factor κB activation in response to bacteria.80 Decreased vitamin D intake has also been associated with differences in fecal microbiota in a small study,81 findings that are consistent with the alterations noted among our group of pregnant adolescents.

There are several plausible biological mechanisms by which vitamin D could modulate heme metabolism, such as via decreased inflammation or through the recent associations noted between vitamin D and hepcidin. To our knowledge, the observed association between vitamin D status and heme catabolic metabolites in quintile analyses has not previously been investigated in metabolomic studies. However, findings are consistent with previous analyses in HIV-infected pregnant women, in which sufficient maternal vitamin D status was associated with decreased risk of anemia and iron deficiency3,5 and predicted resolution of these outcomes.3 Vitamin D deficiency has also been associated with marrow myelofibrosis, a known cause of anemia.82 An association between low vitamin D status and iron deficiency has been observed in studies in individuals with renal disease in National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey III,83 and in studies among children in Bangladeshi, Pakistani, and Indian,84 and Asian85 communities in Britain.

Our study has several limitations. We acknowledge that this is a descriptive, exploratory study that constrains our ability to interpret causality and specific mechanisms and metabolic pathways implicated. In this study, we followed recommendations of the 2011 US IOM guidelines and utilized total circulating 25(OH)D as an index of vitamin D status in this healthy North American population. The cutoff for adequate vitamin D status (25(OH)D > 20 ng/mL) in this analysis was selected to be consistent with recent IOM guidelines for optimal calcium homeostasis and bone health. This issue also remains controversial: the Endocrine Society recently released guidelines for the clinical care of vitamin D deficiency, which differ from the 2011 IOM guidelines, recommending that pregnant women and adolescents maintain serum 25(OH)D concentrations >30 ng/mL. Only 18% of adolescents in this population would meet criteria for vitamin D sufficiency using a cutoff of >30 ng/mL. Given that this research was conducted among healthy pregnant women, we believe the US IOM guidelines are the most appropriate and conservative to utilize in this group. Findings remained similarly significant if comparisons were made between the highest (25(OH)D ≥ 32 ng/mL) and the lowest (≤10 ng/mL) quintiles. Low vitamin D status could also be due to other nonspecific factors related to illness; however, we excluded participants with known medical complications in this study, and all adolescents studied were otherwise healthy and experiencing uncomplicated pregnancies, minimizing potential reverse causation. This analysis was conducted only among a subset of African American adolescents at midgestation. The small sample size and lack of racial diversity limits statistical power and may affect the generalizability of these findings. Although maternal vitamin D status was based on midgestation values, data from the larger cohort found that values were not significantly different from midgestation until delivery.8 The low number of biochemical differences and lack of segregation by principal components analysis could indicate that vitamin D does not have a major impact on serum biochemical profiles; however, this could also be due to the relatively low sample number per group and high biochemical variability observed in humans. However, to our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the role of vitamin D in metabolomic profiles in pregnancy and thus has an important role in hypothesis generation and may inform future research pursuing these associations in larger prospective studies in pregnant women.

In conclusion, maternal 25(OH)D status significantly influenced serum metabolic profiles in a group of healthy, African American pregnant adolescents. Lower maternal vitamin D status was associated with alterations in biochemical parameters, which may be associated with inflammation, oxidative stress, fatty acid β-oxidation, and gut microbiome. The associations noted are supported by existing data on vitamin D status and these same metabolites using published animal and human data. Future work is needed to examine metabolic pathways linked to potential alterations in these metabolites, to assess metabolomic profiles for the parent vitamin D compound and other vitamin D metabolites, and to identify longer term implications of these findings for maternal and neonatal health outcomes.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the mothers and children and the midwives of the Strong Midwifery Group and the adolescents and their infants who made this research possible.

Footnotes

Authors’ Note: This study was conducted at the Strong Health Midwifery Group, University of Rochester.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was supported by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) 2005-35200-15218, USDA 2010-34324-20769, and AFRI/USDA 2011-03424.

References

- 1. Holmes VA, Barnes MS, Alexander HD, McFaul P, Wallace JM. Vitamin D deficiency and insufficiency in pregnant women: a longitudinal study. Br J Nutr. 2009;102 (6):876–881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. O'Riordan MN, Kiely M, Higgins JR, Cashman KD. Prevalence of suboptimal vitamin D status during pregnancy. Ir Med J. 2008;101(8):240, 242–243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Finkelstein JL, Mehta S, Duggan CP, et al. Predictors of anaemia and iron deficiency in HIV-infected pregnant women in Tanzania: a potential role for vitamin D and parasitic infections. Public Health Nutr. 2012;15 (5):928–937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Prentice A, Jarjou LM, Goldberg GR, Bennett J, Cole TJ, Schoenmakers I. Maternal plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentration and birthweight, growth and bone mineral accretion of Gambian infants. Acta Paediatrica. 2009;98 (8):1360–1362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mehta S, Spiegelman D, Aboud S, et al. Lipid-soluble vitamins A, D, and E in HIV-infected pregnant women in Tanzania. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2010;64 (8):808–817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Brannon PM, Picciano MF. Vitamin D in pregnancy and lactation in humans. Ann Rev Nutr. 2011;31:89–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Davis LM, Chang SC, Mancini J, Nathanson MS, Witter FR, O'Brien KO. Vitamin D insufficiency is prevalent among pregnant African American adolescents. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2010;23 (1):45–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Young BE, McNanley TJ, Cooper EM, et al. Vitamin D insufficiency is prevalent and vitamin D is inversely associated with parathyroid hormone and calcitriol in pregnant adolescents. J Bone Miner Res. 2012;27 (1):177–186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Grover SR, Morley R. Vitamin D deficiency in veiled or dark-skinned pregnant women. Med J Aust. 2001;175 (5):251–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. van der Meer IM, Karamali NS, Boeke AJ, et al. High prevalence of vitamin D deficiency in pregnant non-Western women in The Hague, Netherlands. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;84(2):350–353; quiz 468–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Alfaham M, Woodhead S, Pask G, Davies D. Vitamin D deficiency: a concern in pregnant Asian women. Br J Nutr. 1995;73 (6):881–887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kazemi A, Sharifi F, Jafari N, Mousavinasab N. High prevalence of vitamin D deficiency among pregnant women and their newborns in an Iranian population. J Womens Health. 2009;18 (6):835–839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sachan A, Gupta R, Das V, Agarwal A, Awasthi PK, Bhatia V. High prevalence of vitamin D deficiency among pregnant women and their newborns in northern India. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;81 (5):1060–1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Dasgupta A, Saikia U, Sarma D. Status of 25(OH)D levels in pregnancy: A study from the North Eastern part of India. Indian J Endocrinol Metabol. 2012;16 (suppl 2):S405–S407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Young BE, McNanley TJ, Cooper EM, et al. Maternal vitamin D status and calcium intake interact to affect fetal skeletal growth in utero in pregnant adolescents. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;95 (5):1103–1112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Evans KN, Bulmer JN, Kilby MD, Hewison M. Vitamin D and placental-decidual function. J Soc Gynecol Investig. 2004;11 (5):263–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Evans KN, Nguyen L, Chan J, et al. Effects of 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 on cytokine production by human decidual cells. Biol Reprod. 2006;75 (6):816–822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kumar R, Cohen WR, Silva P, Epstein FH. Elevated 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D plasma levels in normal human pregnancy and lactation. J Clin Invest. 1979;63 (2):342–344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Liu NQ, Hewison M. Vitamin D, the placenta and pregnancy. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2012;523 (1):37–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Whitehouse AJ, Holt BJ, Serralha M, Holt PG, Kusel MM, Hart PH. Maternal serum vitamin D levels during pregnancy and offspring neurocognitive development. Pediatrics. 2012;129 (3):485–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sorensen IM, Joner G, Jenum PA, Eskild A, Torjesen PA, Stene LC. Maternal serum levels of 25-hydroxy-vitamin D during pregnancy and risk of type 1 diabetes in the offspring. Diabetes. 2012;61 (1):175–178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bodnar LM, Catov JM, Simhan HN, Holick MF, Powers RW, Roberts JM. Maternal vitamin D deficiency increases the risk of preeclampsia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92 (9):3517–3522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Robinson CJ, Alanis MC, Wagner CL, Hollis BW, Johnson DD. Plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels in early-onset severe preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;203(4):366, e361–e366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Powe CE, Seely EW, Rana S, et al. First trimester vitamin D, vitamin D binding protein, and subsequent preeclampsia. Hypertension. 2010;56 (4):758–763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Baker AM, Haeri S, Camargo CA, Jr, Espinola JA, Stuebe AM. A nested case-control study of midgestation vitamin D deficiency and risk of severe preeclampsia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95 (11):5105–5109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ma R, Gu Y, Zhao S, Sun J, Groome LJ, Wang Y. Expressions of vitamin D metabolic components VDBP, CYP2R1, CYP27B1, CYP24A1, and VDR in placentas from normal and preeclamptic pregnancies. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2012;303 (7):E928–E935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Brannon PM. Vitamin D and adverse pregnancy outcomes: beyond bone health and growth. Proc Nutr Soc. 2012;71 (2):205–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Urrutia RP, Thorp JM. Vitamin D in pregnancy: current concepts. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2012;24 (2):57–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chang SC, O'Brien KO, Nathanson MS, Mancini J, Witter FR. Characteristics and risk factors for adverse birth outcomes in pregnant black adolescents. J Pediatr. 2003;143 (2):250–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bodnar LM, Krohn MA, Simhan HN. Maternal vitamin D deficiency is associated with bacterial vaginosis in the first trimester of pregnancy. J Nutr. 2009;139 (6):1157–1161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hensel KJ, Randis TM, Gelber SE, Ratner AJ. Pregnancy-specific association of vitamin D deficiency and bacterial vaginosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;204(1):41, e41–e49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Scholl TO, Chen X. Vitamin D intake during pregnancy: association with maternal characteristics and infant birth weight. Early Hum Dev. 2009;85 (4):231–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Marya RK, Rathee S, Dua V, Sangwan K. Effect of vitamin D supplementation during pregnancy on foetal growth. Indian J Med Res. 1988;88:488–492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hollis BW, Johnson D, Hulsey TC, Ebeling M, Wagner CL. Vitamin D supplementation during pregnancy: double-blind, randomized clinical trial of safety and effectiveness. J Bone Miner Res. 2011;26 (10):2341–2357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hollis BW, Wagner CL. Vitamin D and pregnancy: skeletal effects, nonskeletal effects, and birth outcomes. Calcif Tissue Int. 2013;92 (2):128–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Finkelstein JL, Mehta S, Duggan C, et al. Maternal vitamin D status and child morbidity, anemia, and growth in human immunodeficiency virus-exposed children in Tanzania. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2012;31 (2):171–175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Litonjua AA, Weiss ST. Is vitamin D deficiency to blame for the asthma epidemic? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;120 (5):1031–1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Brehm JM, Schuemann B, Fuhlbrigge AL, et al. Serum vitamin D levels and severe asthma exacerbations in the Childhood Asthma Management Program study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;126(1):52–58. e55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Walker VP, Modlin RL. The vitamin D connection to pediatric infections and immune function. Pediatr Res. 2009;65(5 pt 2):106R–113R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bouillon R, Van Schoor NM, Gielen E, et al. Optimal vitamin D status: a critical analysis on the basis of evidence-based medicine. J Clin Endocrinol Metabol. 2013;98 (8):E1283–E1304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Holick MF. Evidence-based D-bate on health benefits of vitamin D revisited. Dermatoendocrinology. 2012;4 (2):183–190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Holick MF. Environmental factors that influence the cutaneous production of vitamin D. Am J Clin Nutr. 1995;61(3 suppl):638S–645S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Elnenaei MO, Chandra R, Mangion T, Moniz C. Genomic and metabolomic patterns segregate with responses to calcium and vitamin D supplementation. Br J Nutr. 2011;105 (1):71–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. O'Brien KO, Donangelo CM, Ritchie LD, Gildengorin G, Abrams S, King JC. Serum 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D and calcium intake affect rates of bone calcium deposition during pregnancy and the early postpartum period. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;96 (1):64–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. O'Brien KO, Li S, Cao C, et al. Placental CYP27B1 and CYP24A1 expression in human placental tissue and their association with maternal and neonatal calcitropic hormones. J Clin Endocrinol Metabol. 2014;99 (4):1348–1356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Young BE, Cooper EM, McIntyre AW, et al. Placental vitamin D receptor (VDR) expression is related to neonatal vitamin D status, placental calcium transfer, and fetal bone length in pregnant adolescents. FASEB J. 2014;28 (5):2029–2037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Whisner CM, Young BE, Witter FR, et al. Reductions in heel bone quality across gestation are attenuated in pregnant adolescents with higher pre-pregnancy weight and greater increases in PTH across gestation. J Bone Miner Res. 2014;29 (9):2109–2117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Essley BV, McNanley T, Cooper EM, et al. Osteoprotegerin differs by race and is related to infant birth weight z-score in pregnant adolescents. J Dev Orig Health Dis. 2011;2 (5):272–279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Bar HY, Booth JG, Wells MT. A mixture-model approach for parallel testing for unequal variances. Stat Appl Genet Mol Biol. 2012;11(1):Article 8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Hollis BW. Circulating 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels indicative of vitamin D sufficiency: implications for establishing a new effective dietary intake recommendation for vitamin D. J Nutr. 2005;135 (2):317–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Holick MF. Vitamin D deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2007;357 (3):266–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Durrleman S, Simon R. Flexible regression models with cubic splines. Stat Med. 1989;8 (5):551–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Govindarajulu US, Spiegelman D, Thurston SW, Ganguli B, Eisen EA. Comparing smoothing techniques in Cox models for exposure-response relationships. Stat Med. 2007;26 (20):3735–3752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Greenland S. Modeling and variable selection in epidemiologic analysis. Am J Public Health. 1989;79 (3):340–349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Sonnenburg JL, Chen CT, Gordon JI. Genomic and metabolic studies of the impact of probiotics on a model gut symbiont and host. PLoS Biol. 2006;4 (12):e413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Pokusaeva K, Fitzgerald GF, van Sinderen D. Carbohydrate metabolism in Bifidobacteria. Genes Nutr. 2011;6 (3):285–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Heazell AE, Bernatavicius G, Warrander L, Brown MC, Dunn WB. A metabolomic approach identifies differences in maternal serum in third trimester pregnancies that end in poor perinatal outcome. Reprod Sci. 2012;19 (8):863–875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Conde-Agudelo A, Papageorghiou AT, Kennedy SH, Villar J. Novel biomarkers for predicting intrauterine growth restriction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BJOG. 2013;120 (6):681–694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. O'sullivan A, Gibney MJ, Connor AO, et al. Biochemical and metabolomic phenotyping in the identification of a vitamin D responsive metabotype for markers of the metabolic syndrome. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2011;55(5):679–690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Carraro S, Giordano G, Reniero F, et al. Asthma severity in childhood and metabolomic profiling of breath condensate. Allergy. 2013;68 (1):110–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Fischer R, Trudgian DC, Wright C, et al. Discovery of candidate serum proteomic and metabolomic biomarkers in ankylosing spondylitis. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2012;11(2):M111 013904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Oberbach A, Bluher M, Wirth H, et al. Combined proteomic and metabolomic profiling of serum reveals association of the complement system with obesity and identifies novel markers of body fat mass changes. J Proteome Res. 2011;10 (10):4769–4788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Weber G, Heilborn JD, Chamorro Jimenez CI, Hammarsjo A, Torma H, Stahle M. Vitamin D induces the antimicrobial protein hCAP18 in human skin. J Investig Dermatol. 2005;124 (5):1080–1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Yim S, Dhawan P, Ragunath C, Christakos S, Diamond G. Induction of cathelicidin in normal and CF bronchial epithelial cells by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D(3). J Cyst Fibros. 2007;6 (6):403–410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Liu PT, Stenger S, Tang DH, Modlin RL. Cutting edge: vitamin D-mediated human antimicrobial activity against Mycobacterium tuberculosis is dependent on the induction of cathelicidin. J Immunol. 2007;179 (4):2060–2063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Diaz L, Noyola-Martinez N, Barrera D, et al. Calcitriol inhibits TNF-alpha-induced inflammatory cytokines in human trophoblasts. J Reprod Immunol. 2009;81 (1):17–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Yang S, Smith C, Prahl JM, Luo X, DeLuca HF. Vitamin D deficiency suppresses cell-mediated immunity in vivo. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1993;303 (1):98–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Bar-Shavit Z, Noff D, Edelstein S, Meyer M, Shibolet S, Goldman R. 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 and the regulation of macrophage function. Calcif Tissue Int. 1981;33 (6):673–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Mariani E, Ravaglia G, Forti P, et al. Vitamin D, thyroid hormones and muscle mass influence natural killer (NK) innate immunity in healthy nonagenarians and centenarians. Clin Exp Immunol. 1999;116 (1):19–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Yin Y, Yu Z, Xia M, Luo X, Lu X, Ling W. Vitamin D attenuates high fat diet-induced hepatic steatosis in rats by modulating lipid metabolism. Eur J Clin Investig. 2012;42 (11):1189–1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Wong KE, Szeto FL, Zhang W, et al. Involvement of the vitamin D receptor in energy metabolism: regulation of uncoupling proteins. Am J Phys. 2009;296 (4):E820–828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Wong KE, Kong J, Zhang W, et al. Targeted expression of human vitamin D receptor in adipocytes decreases energy expenditure and induces obesity in mice. J Biol Chem. 2011;286 (39):33804–33810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Davis WL, Matthews JL, Goodman DB. Glyoxylate cycle in the rat liver: effect of vitamin D3 treatment. FASEB J. 1989;3 (5):1651–1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Zemel MB, Shi H, Greer B, Dirienzo D, Zemel PC. Regulation of adiposity by dietary calcium. FASEB J. 2000;14 (9):1132–1138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Barengolts E. Vitamin D and prebiotics may benefit the intestinal microbacteria and improve glucose homeostasis in prediabetes and type 2 diabetes. Endocr Pract. 2013;19 (3):497–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Ly NP, Litonjua A, Gold DR, Celedon JC. Gut microbiota, probiotics, and vitamin D: interrelated exposures influencing allergy, asthma, and obesity? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127(5):1087–1094; quiz 1095–1086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Griffin MD, Xing N, Kumar R. Vitamin D and its analogs as regulators of immune activation and antigen presentation. Ann Rev Nutr. 2003;23:117–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Adorini L, Penna G. Dendritic cell tolerogenicity: a key mechanism in immunomodulation by vitamin D receptor agonists. Hum Immunol. 2009;70 (5):345–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Yu S, Bruce D, Froicu M, Weaver V, Cantorna MT. Failure of T cell homing, reduced CD4/CD8alphaalpha intraepithelial lymphocytes, and inflammation in the gut of vitamin D receptor KO mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105 (52):20834–20839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Wu S, Liao AP, Xia Y, et al. Vitamin D receptor negatively regulates bacterial-stimulated NF-kappaB activity in intestine. Am J Pathol. 2010;177 (2):686–697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Mai V, McCrary QM, Sinha R, Glei M. Associations between dietary habits and body mass index with gut microbiota composition and fecal water genotoxicity: an observational study in African American and Caucasian American volunteers. Nutr J. 2009;8:49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Yetgin S, Ozsoylu S, Ruacan S, Tekinalp G, Sarialioglu F. Vitamin D-deficiency rickets and myelofibrosis. J Pediatr. 1989;114 (2):213–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Kendrick J, Smits G, Chonchol M. 25-Hydroxyvitamin D and inflammation and its association with hemoglobin levels in chronic kidney disease. Paper presented at: National Kidney Foundation Spring Clinical Meetings; April 2008; Dallas, TX. [Google Scholar]

- 84. Lawson M, Thomas M. Vitamin D concentrations in Asian children aged 2 years living in England: population survey. BMJ. 1999;318 (7175):28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Grindulis H, Scott PH, Belton NR, Wharton BA. Combined deficiency of iron and vitamin D in Asian toddlers. Arch Dis Child. 1986;61 (9):843–848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]