Abstract

The Erasmus syndrome describes the association of generalised systemic sclerosis following exposure to silica with or without silicosis. This is a case report on a male patient presenting with this syndrome. Radiological changes of silicosis have preceded the diagnosis of systemic sclerosis by 6 years and occupational exposure has been stopped. The clinical features did not differ from systemic sclerosis in general. The evolution was marked by a progression of skin lesions whereas pulmonary lesion remained stable.

Background

In 1957, Erasmus pointed out the relationship between exposure to silica and the occurrence of systemic sclerosis (SSc) among a group of gold miners.1 Other observations and some case–control or cohort studies came subsequently to support the reality of this risk and pathogenic hypotheses were advanced. We describe an original case of a patient followed for pulmonary silicosis who developed a progressive diffuse SSc 6 years later.

Case presentation

In 2000, a 53-year-old man, smoking 20 pack-years, consulted for the onset of Raynaud’s phenomenon rapidly followed by oedema of the hands and inflammatory polyarthralgia of large and small joints (knees, wrists, metacarpophalangeal and proximal interphalangeal joints). He also reported effort dyspnoea and dysphagia to solids. Physical examination on admission revealed skin sclerosis of the hands, forearms, feet, thorax and face. The nose was sharp and the mouth opening was limited to two finger breadths. This sclerosis was accompanied by diffuse depigmented areas and pulp ulceration. The mobility of large joints was hampered without arthritis. Auscultation revealed crackles in the lung bases.

Investigations

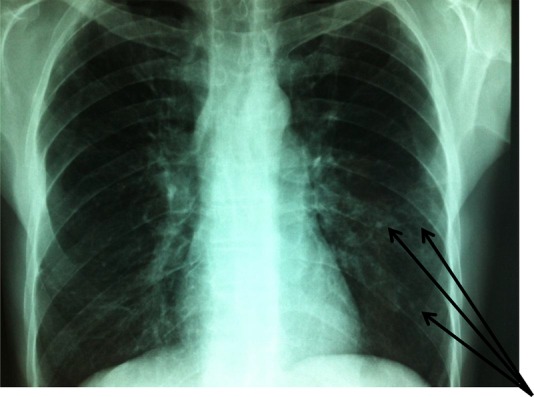

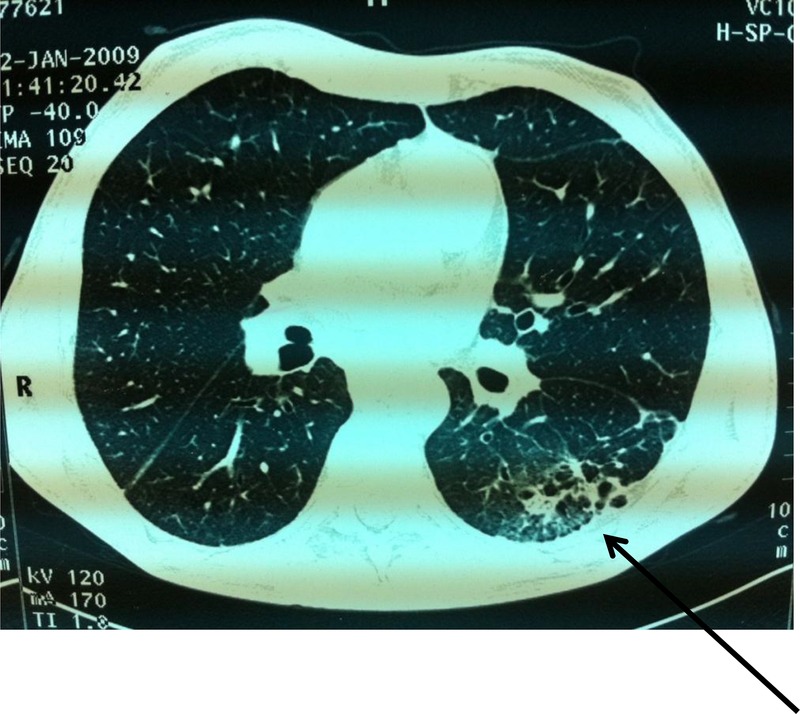

Laboratory tests were normal (blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C reactive protein). Antinuclear antibodies were positive at 1/800 (homogeneous pattern) and anti-Scl 70 antibodies were positive at four cross marks. Anti-extractable nuclear antibodies (ENA) and the anti-DNA native antibodies and rheumatoid factor were negative. Capillaroscopy showed specific organic microangiopathy. Skin biopsy confirmed the diagnosis of scleroderma. Digestive endoscopy revealed oesophagitis (stage 2). Oesophageal manometry showed a hypotonic lower oesophageal sphincter and aperistalsis of the lower two-thirds of the oesophagus. Standard radiographs showed erosion of the ulnar styloid with metacarpal pinching (figure 1). Chest radiograph showed interstitial syndrome with a parahilar and left pulmonary base reticulonodular appearance (figure 2). A chest CT scan revealed multiple foci of parenchymal retractile condensation of the left basal pyramid with bronchiectasis through traction and hyperdensity ranges in frosted glass. There were multiple bilateral calcified micronodules of the apical segments and subpleural nodules in the two upper lobes associated with centrolobular emphysaema, as well as an adenomegaly of the laterotracheal lymphs, bifurcation group and left anterior mediastinal chain, some of which were calcified. The appearance was consistent with pulmonary silicosis (figure 3). History re-examination revealed that the patient had worked in a quarry for 8 years and a diagnosis of pulmonary silicosis had been made 6 years prior to the current presentation, in front of a typical radiographic appearance and the notion of occupational exposure. He had since benefitted from occupational reclassification. Pulmonary function tests revealed a moderate restrictive defect with decreased functional vital capacity to 83%. The diagnosis of SSc (American College of Rheumatology criteria) occurring in the context of pulmonary silicosis (International Labor Office criteria) was retained.

Figure 1.

Erosion of the ulnar styloid with metacarpal pinching.

Figure 2.

Interstitial syndrome with a para-hilar and left pulmonary base reticulo-nodular appearance.

Figure 3.

Chest CT scan: parenchymal retractile condensation of the left basal pyramid with bronchiectasis and hyperdensity ranges in frosted glass.

Treatment

The patient was treated with calcium channel blockers (nifedipine 40 mg/day), corticosteroids (prednisone 10 mg/day), D-penicillamine (900 mg/day), colchicine (1 mg per day) and inhibitors of the proton pump.

Outcome and follow-up

The evolution was marked by a progression of skin lesions with extension of the sclerosis to the abdomen, with a flexion contracture of the elbow, left wrist and trigger fingers. Pulmonary lesion was clinically and radiologically stable and the data from pulmonary function testing remained unchanged for a 12-year follow-up.

Discussion

An increased prevalence of autoimmune diseases has been demonstrated in people with occupational exposure to silica. SSc was the first disease for which a relationship with exposure to silica was established. Originator cases reported by Erasmus involved 16 patients with SSc among a group of 8000 gold miners, six of whom had associated silicosis.1 Since then, other observations of SSc have been reported in patients with occupational exposure to silica, with or without pulmonary silicosis. Epidemiological studies such as the case–control study of Sluis-Cremer confirmed the link between silica exposure and SSc.2 Out of a population of 187 men with SSc, 111 were exposed to silica for extended periods and 57 suffered from silicosis.3 In personnel exposed to silica, scleroderma percentage ranges from 16% to 37%.3 A similar pattern has been reported with other environmental agents, in particular coal and some organic solvents.4 5

Apart from SSc,6 chronic exposure to silica seems to favour the occurrence of other autoimmune diseases, especially rheumatoid arthritis, with a prevalence of 5%,7 systemic lupus erythaematosus,8 9 dermatomyositis and other autoimmune diseases.9 The most common connective tissue disease among silicotics in the Michigan disease registry was not SSc but rheumatoid arthritis.10 Our patient did not fulfil criteria for rheumatoid arthritis or mixed connective tissue disease.

Clinically, SSc associated with exposure to silica seems to be indistinguishable from idiopathic SSc.11 On the biological level, the presence of antinuclear autoantibodies and anti-Scl 70 is found with the same frequency as outside exposure to silica.11 12 It should be noted that anti-Scl 70 was detected in 10.1% of patients with silicosis without any clinical manifestation of autoimmune disease, suggesting its relationship with pulmonary fibrosis.13

SSc is recognised as an occupational disease in some countries. Many professions expose workers to silica and sources of exposure are classified into two major sectors: ‘extraction’ sectors (mines, rock quarries and tunnelling) and ‘use’ sectors (foundries, glass and ceramics industries).

The mechanism of SSc occurrence after exposure to silica responds to a stimulation of the proliferation of monocyte-alveolar macrophages by the inhaled silicon dioxide crystals, causing the release of cytokines such as profibrosing interleukin 1 and fibroblast growth factor, which activate fibroblasts, and enhance their collagen and glycosaminoglycan synthesis.14 15

The prognosis depends on the lung lesion that can respond to a dual mechanism in relation to silicosis or SSc. In our patient, the lung lesion was slowly progressive and the impact on the respiratory function was moderate.

Stopping the exposure to toxic agents in some cases can stabilise the progression of the disease and even improve it. This was not the case in our patient, whose skin lesions worsened despite occupational reclassification, resulting in a pattern of diffuse scleroderma. Colchicine, which is a compound capable of inhibiting the accumulation of collagen by blocking the conversion of procollagen to collagen, has been ineffective in treating the cutaneous aspect of scleroderma in our patient. The effect of colchicine has been evaluated in some very old, short-term trials, most of which deemed it as negative.16 17 A study had suggested improvement in 19 patients (15 with diffuse disease) treated for 19–57 months with Colchicine, however, there was no comparison with a control group.18

Learning points.

Consider a thorough professional investigation when diagnosing systemic sclerosis (SSc).

The demonstrated role of exposure to silica in the pathophysiology of SSc and other autoimmune diseases calls for strengthening the tools of professional protection and imposing strict control.

Stopping the exposure to toxic agents is mandatory when diagnosing autoimmune disease.

Footnotes

Contributors: KBA, AF and LS were involved in the conception and design, drafting of the manuscript, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. LZ gave the final approval.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Erasmus LD. Scleroderma in gold-miners on the Witwatersrand with particular reference to pulmonary manifestations. S Aft J Lab Clin Med 1957;3:209–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sluis-Cremer GK, Hessel PA, Nizdo EH et al. Silica, silicosis, and progressive systemic sclerosis. Br J Ind Med 1985;4:838–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haustein UF, Anderegg U. Silica induced scleroderma- clinical and experimental aspects. J Rheumatol 1998;25:1917–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rodman GP, Benedek TG, Medsger TA et al. The association of progressive systemic sclerosis with coal miner's pneumoconiosis and other forms of silicosis. Ann Intern Med 1967;66:323–4. 10.7326/0003-4819-66-2-323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Diot E, Lesire V, Guilmot JL et al. Systemic sclerosis and occupational risk factors: a case–control study. Occup Environ Med 2002;59:545–9. 10.1136/oem.59.8.545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McCormic ZD, Khuder SS, Aryal BK et al. Occupational silica exposure as a risk factor for scleroderma: a meta-analysis. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 2010;83:763–9. 10.1007/s00420-009-0505-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rosenman KD, Moore-Fuller M, Reilly MJ. Connective tissue disease and silicosis. Am J Ind Med 1999;35:375–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Costallat LT, De Capitani EM, Zambon L. Pulmonary silicosis and systemic lupus erythematosus in men: a report of two cases. Joint Bone Spine 2002;69:68–71. 10.1016/S1297-319X(01)00344-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koeger AC, Lang T, Alcaix D et al. Silica-associated connective tissue disease. A study of 24 cases. Medicine (Baltimore) 1995;74:221–37. 10.1097/00005792-199509000-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Makol A, Reilly MJ, Rosenman KD. Prevalence of connective tissue disease in silicosis (1985–2006)-a report from the state of Michigan surveillance system for silicosis. Am J Ind Med 2011;54:255–62. 10.1002/ajim.20917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rustin MH, Bull HA, Ziegler V et al. Silica-associated systemic sclerosis is clinically, serologically and immunologically indistinguishable from idiopathic systemic sclerosis. Br J Dermatol 1990;123:725–34. 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1990.tb04189.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zaghi G, Koga F, Nisihara RM et al. Autoantibodies in silicosis patients and in silica-exposed individuals. Rheumatol Int 2010;30:1071–5. 10.1007/s00296-009-1116-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tomokuni A, Otsuki T, Sakaguchi H et al. Detection of anti-topoisomerase I autoantibody in patients with silicosis. Environ Health Prev Med 2002;7:7–10. 10.1007/BF02898059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haustein UF, Ziegler V, Herrmann K et al. Silica-induced scleroderma. J Am Acad Dermatol 1990;22:444–8. 10.1016/0190-9622(90)70062-M [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miranda AA, Nascimento AC, Peixoto IL et al. Erasmus syndrome—silicosis and systemic sclerosis. Rev Bras Reumatol 2013;53:310–3. 10.1590/S0482-50042013000300010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Medsger TA., Jr Treatment of systemic sclerosis. Ann Rheum Dis 1991;50:877–86. 10.1136/ard.50.Suppl_4.877 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guttadauria M, Diamond H, Kaplan D. Colchicine in the treatment of scleroderma. J Rheumatol 1977;4:272–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alarcon-Segovia D, Ramos-Niembro F, Ibanez de Kasep G et al. Long-term evaluation of colchicine in the treatment of scleroderma. J Rheumatol 1979;6:705–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]