Abstract

Background

Chronic sinusitis (CRS) is a common otorhinolaryngologic disease that is frequently encountered in everyday practice, but there is a lack of precise data regarding the prevalence of CRS in developing countries. We performed a national investigation in China to determine the prevalence and associated factors of CRS.

Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional investigation in 2012. A stratified four-stage sampling method was used to select participants randomly from seven cities in mainland China. All participants were interviewed face-to-face via a standardized questionnaire. Unconditional logistic regression analyses were conducted to examine the association between smoking and sinusitis after adjusting for socio-demographic factors.

Results

This study included a total of 10 636 respondents from seven cities. The overall prevalence of CRS was 8.0% and ranged from 4.8% to 9.7% in seven centres. Chronic sinusitis affected approximately 107 million people in mainland China. Chronic sinusitis was particularly prevalent among people with specific medical conditions, including allergic rhinitis, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and gout. The prevalence was slightly higher among males (8.79%) than females (7.28%) (P = 0.004), and the prevalence varied by age group, ethnicity and marital status and education (P < 0.05), but not by household per capita income or living space (P > 0.05). Both second-hand tobacco smoke and active smoking were independent risk factors for CRS (P = 0.001).

Conclusions

Chronic sinusitis is an important public health problem in China. Our study provides important information for the assessment of the economic burden of CRS and the development and promotion of public health policies associated with CRS particularly in developing countries.

Keywords: China, chronic sinusitis, prevalence, smoking, socio-demographic

Chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) is characterized by inflammation of the mucosa of the nose and paranasal sinuses with a duration of at least 12 consecutive weeks and is a common otorhinolaryngologic disease that is frequently encountered in everyday practice (1). Although CRS is not a life-threatening disease, not all patients are cured or achieve control of their symptoms, even with maximal medical management or surgical intervention. The symptoms in CRS patients with (CRSwNP) and without nasal polyps (CRSsNP) are considerably overlapping, while patients with CRSwNP have higher symptom scores and more nasal symptoms (2). Patients with CRSwNP are particularly recalcitrant to usual therapies, and this type of CRS is increasingly prevalent (3). The persistent symptoms can result in facial pain/headache, impairments in general health, vitality and social functioning, stress disorders and other problems that affect patients’ lives and work (4–7).

The European Position Paper on Rhinosinusitis and Nasal Polyps (EP3OS) group proposed clear guidelines for a symptom-based definition of rhinosinusitis that has been validated and accepted in epidemiological studies (1,8,9). The European postal survey of 57 128 adults in 12 countries reported that the overall prevalence of EP3OS-defined CRS was 10.9% and ranged from 6.9% to 27.1% in 19 centres (10). A recent survey reported a prevalence of EP3OS-defined CRS of 5.51% in Sao Paulo, Brazil (11). Some authors have used the data from the National Population Health Survey to estimate the prevalence of CRS and found prevalences of 6.95% in Korea (12) and 5.7% among female and 3.4% among male Canadians (13). The 2012 National Health Interview Survey of 34 525 adults found that 12% of adults have been told by a doctor or other health professional that they have sinusitis, and these self-reported doctor-diagnosed prevalences of sinusitis were 15% and 9% among males and females, respectively. The vital health statistic data revealed that CRS is more prevalent than other common chronic respiratory diseases, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (3%) and asthma (8%) (14). Based on this high prevalence, some studies in the USA have claimed that CRS poses an enormous health and economic burden to individuals, the community and society (15). When accounting for the entire population into account, the health burden of CRS is speculated to be huge in Asia; nevertheless, little is known about the actual situation.

A survey of 4554 Danes reported a CRS prevalence of 7.8% compared to the overall prevalence of 10.9% in 19 European centres (10,16). The National Health Interview Survey of US adults revealed a decreasing trend in CRS from 16% in 1997 to 14% in 2006 and 12% in 2012 (14,17,18). The literature suggests that the prevalence and patterns of CRS might vary by region and population and change over time due to environmental changes and the development of health care. The previous epidemiological data regarding CRS are mainly from western studies, and little is known regarding the potential socio-economic disparities. In Asia, large-scale epidemiological studies are required to update information about the prevalence of CRS, and such studies would provide information for the assessment of the disease burden and the development and promotion of public health policies associated with CRS.

We conducted a cross-sectional investigation in seven major Chinese cities. This study aimed to provide a better understanding of the epidemiological characteristics of CRS, including its prevalence and associations with socio-economic factors and tobacco smoke.

Methods

Participants and sampling

We selected seven Chinese cities, including Urumqi, Changchun, Beijing, Wuhan, Chengdu, Huaian and Guangzhou. Geographically, these cities cover the north, middle and south of China with diverse climates and socio-economics.

The participants were selected using stratified four-stage random sampling method. The entire process was performed using a unified protocol and a standardized computer random sampling program. For each city (the strata), based on the list of administrative districts, streets and communities, the coordinator of this study randomly sampled two districts and subsequently used simple random sampling to select two streets within each selected district and two communities from each selected street. As a result, 56 communities (eight communities in each city) were selected. In the final stage, the investigator in each city performed cluster sampling. Approximately 65 households from each community were randomly sampled according to the door numbers provided by the local communities. The target subjects were all Chinese residents of chosen households who had lived in the local region for at least 1 year at the time the study was conducted.

Instruments and data collection

The participants were interviewed face-to-face in their own houses, and they were asked to complete a standardized questionnaire. The questionnaire was developed by the Global Allergy and Asthma European Network (GA2LEN) project (10) and covers socio-demographic characteristics and CRS-related symptoms. According to EP3OS document (1,8,9,19), CRS is defined based on the presence of two or more of the following symptoms and at least one of the first two symptoms being present for more than 12 weeks in the last 1 year: nasal obstruction/blockage/congestion, nasal discharge (anterior/posterior/nasal drip or purulent throat mucus), facial (forehead/nasal/eye) pain/pressure, and a reduction or loss of smell. In principle, the questionnaire was self-administered, but ghostwriting by the parents was allowed for children, and assistance from trained interviewers was provided for illiterate participants and for clarification of the questions.

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of The First Affiliated Hospital, Sun Yat-sen University (the principle centre), China. The interviewer explained the purpose of the investigation and the procedures and acquired the informed consent of all subjects involved in the study before commencing the interview.

Statistical analyses

Double data entry and consistency checking were processed using EpiData 3.1. The data analyses were performed using SPSS 19.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) and STATA 12.0 (Stata Corp., College Station, TX, USA). We calculated the crude prevalence of CRS and gender-specific age-standardized prevalence in the Chinese urban population based on the national census data from 2011. The comparisons of the prevalences of CRS between the subgroups were made with chi-square tests, and odds ratio (OR) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were calculated. Multivariate analyses were conducted using binary logistic regression to examine the association between smoking and CRS after adjusting for socio-demographic factors. The score test for trend of odds was performed to determine the dose–response relationship between smoking and CRS. Two-tailed P values below 0.05 were regarded as indicative of statistical significance.

Results

A total of 10 636 interviewees completed the questionnaires for a response rate of 87%. According to the EP3OS criteria, we identified 851 persons with CRS. The prevalences of nasal blockage, nasal discharge, facial pain/pressure and reductions in the sense of smell in CRS were 90.8%, 77.9%, 48.2% and 57.6%, respectively. Of the persons with CRS, 43.4% and 61.6% had used nasal steroid sprays and antibiotics, respectively, to control these symptoms within the last 1 year. Of the patients with CRS, 6.1% had previously undergone sinus surgery. Five hundred and twenty-seven persons (63.9%) with CRS had been told that they had chronic rhinitis or CRS by a doctor, and 32.4% and 5.8% had self-reported doctor-diagnosed allergic rhinitis and nasal polyps, respectively. The prevalence of self-reported doctor-diagnosed CRS was 4.3%, which was nearly half of the prevalence of self-reported CRS as defined by the EP3OS criteria.

The overall prevalences of CRS were 8.00% (95% CI: 7.50–8.54%) in the general population and 8.2% (95% CI: 7.64–8.76%) among adults aged 15–75 years. There were some geographic variations in CRS; the lowest prevalences were observed in Beijing (4.80%) and Huaian (5.04%), and similar levels were observed in other cities (range 8.42% to 9.66%). The prevalence among males was higher than that among females in the general population (P = 0.004) and in all specific cities with the exception of Chengdu. The age-standardized prevalence was similar to the crude prevalence, and the gender and geographic difference remained after standardization (Table1).

Table 1.

Prevalence of chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) in different cities

| Crude prevalence CRS (%) | Age-standardized prevalence (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| City | Male | Female | Total | Male | Female | Total |

| Beijing | 38 (5.38) | 34 (4.28) | 72 (4.80) | 4.51 | 3.84 | 4.18 |

| Guangzhou | 67 (8.97) | 61 (7.88) | 128 (8.42) | 8.59 | 8.29 | 8.44 |

| Chengdu | 62 (8.90) | 82 (9.90) | 144 (9.44) | 9.31 | 9.45 | 9.38 |

| Urumqi | 87 (12.38) | 56 (7.03) | 143 (9.53) | 11.17 | 7.21 | 9.24 |

| Wuhan | 81 (10.06) | 71 (9.23) | 152 (9.66) | 9.92 | 9.59 | 9.76 |

| Changchun | 69 (9.34) | 67 (8.80) | 136 (9.07) | 10.98 | 9.45 | 10.23 |

| Huaian | 47 (6.40) | 29 (3.75) | 76 (5.04) | 5.57 | 3.45 | 4.56 |

| Total | 451 (8.79) | 400 (7.28) | 851 (8.00) | 8.78 | 7.29 | 8.01 |

In addition to the gender and geographic differences, several other demographic features were associated with CRS (Table2). The prevalence seemed to vary with age and was higher in the middle age group than in the adolescents (OR = 1.44, 95% CI: 1.03–2.02), but the difference between the other age groups was nonsignificant (P > 0.05). The ethnic minorities were approximately 50% more likely to develop CRS than were the Hans (OR = 1.54, 95% CI: 1.17–2.02). A significant association between CRS and marital status was also observed (P = 0.001). Among divorced people, CRS was approximately 1.75 times more prevalent than in married people (OR = 2.75, 95% CI: 1.81–4.18), and the prevalence in unmarried people was also significantly higher than in married people (OR = 1.21, 95% CI: 1.03–1.43), while the difference between widowed people and married people was not statistically significant (OR = 1.20, 95% CI: 0.85–1.68) (Table2).

Table 2.

Comparisons of the prevalence of chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) between different groups

| Factors | Groups | Responders (proportion, %) | CRS (prevalence, %) | OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age group | 0–14 years | 644 (6.07) | 41 (6.37) | 1 |

| 15–34 years | 3136 (29.53) | 280 (8.93) | 1.44 (1.03, 2.02) | |

| 35–b59 years | 4834 (45.52) | 368 (7.61) | 1.21 (0.87, 1.69) | |

| ≥60 years | 2005 (18.88) | 160 (7.98) | 1.27 (0.89, 1.82) | |

| Ethnicity | Han | 10 060 (94.93) | 788 (7.83) | 1 |

| Minority | 537 (5.07) | 62 (11.55) | 1.54 (1.17, 2.02) | |

| Marital status | Married | 7690 (72.57) | 575 (7.48) | 1 |

| Divorced | 154 (1.45) | 28 (18.18) | 2.75 (1.81, 4.18) | |

| Widowed | 431 (4.07) | 38 (8.82) | 1.20 (0.85, 1.68) | |

| Unmarried | 2322 (21.91) | 207 (8.91) | 1.21 (1.03, 1.43) | |

| Education attainment | Illiterate or primary | 1604 (15.10) | 112 (6.98) | 1 |

| Secondary school | 2186 (20.58) | 148 (6.77) | 0.97 (0.75, 1.25) | |

| High school | 3394 (31.95) | 294 (8.66) | 1.26 (1.01, 1.58) | |

| College | 3218 (30.30) | 280 (8.70) | 1.27 (1.01, 1.59) | |

| Master or above | 220 (2.07) | 15 (6.81) | 0.97 (0.55, 1.70) | |

| Household monthly income per person | <RMB $3000 | 7791 (73.43) | 638 (8.19) | 1 |

| RMB $3000+ | 2819 (26.54) | 207 (7.34) | 0.89 (0.76, 1.05) | |

| Floor space per person (m2) | Below median (26.67) | 4385 (48.17) | 349 (7.96) | 1 |

| Above median | 4718 (51.83) | 424 (8.99) | 1.05 (0.91, 1.22) | |

| No. of bedrooms per person | Below median (0.67) | 4827 (53.04) | 401 (8.31) | 1 |

| Above the median | 4274 (46.96) | 371 (8.68) | 1.14 (0.99, 1.32) |

Interestingly, we observed an inverted U-shaped relationship between CRS and education level. The prevalence among people with high school or college educations was higher than that among other groups (P = 0.023). Chronic sinusitis did not change substantially with household income or living area (P = 0.334, 0.524; Table 2).

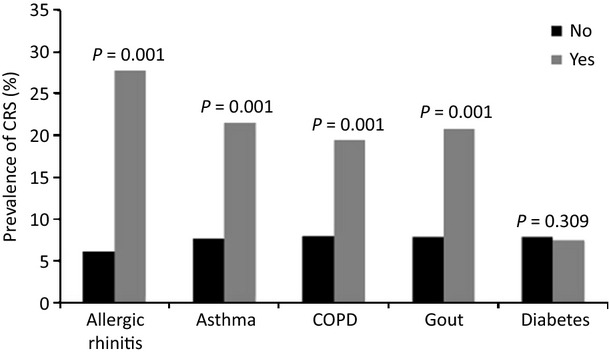

A total of 119 subjects reported doctor-diagnosed nasal polyps (NP) among which 40% had symptoms of CRS in the last 1 year. Chronic sinusitis was more prevalent among people with some particular self-reported doctor-diagnosed diseases; the prevalence of CRS was 30% in patients with allergic rhinitis and 23% in asthmatic patients, much higher as compared to 6% and 7% in subjects without allergic rhinitis or asthma (P < 0.001). Those with a medical history of COPD or gout were about two times more likely to develop CRS than those without such medical history (P < 0.001; Fig.1).

Figure 1.

The prevalence of symptoms in subjects with and without a specific medical condition.

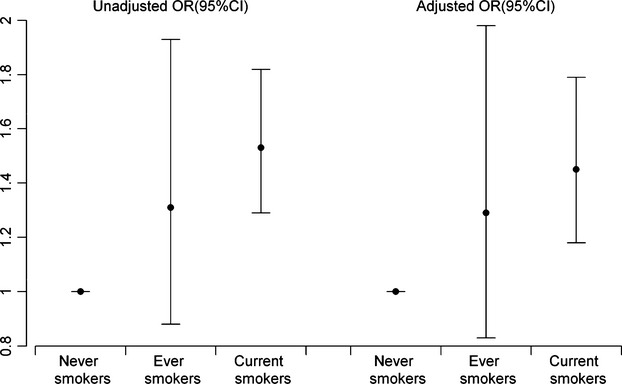

Among all of the subjects, there were 1680 (15.8%) current smokers. The smokers were approximately 50% more likely to have CRS than the never smokers (adjusted OR = 1.44, 95% CI: 1.17–1.77; Fig.2), and the effect of tobacco smoke increased with the cumulative years of smoking (P = 0.001) and the number of cigarettes smoked per day (P = 0.001) with the exception of the smokers of 11–20 cigarettes per day (Table3). There was no clear evidence that former smokers were more susceptible to CRS (adjusted OR = 1.30, 95% CI: 0.84–2.01; Table 4). A greater prevalence was also observed among those who lived or worked with one smoker (adjusted OR = 1.21, 95% CI: 1.03–1.43) compared to those who were not exposed to second-hand smoke. The effect of second-hand tobacco exposure tended to increase with the cumulative years (P = 0.002) and doses of exposure (P = 0.003) (Table4).

Figure 2.

Odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval of chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) associated with smoking.

Table 3.

The effect of current smoking on chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS)

| Non-CRS | CRS | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR (95% CI)* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cumulative years of tobacco smoke | ||||

| Never smokers (reference) | 7994 | 638 | 1 | 1 |

| 1–10 | 210 | 28 | 1.67 (1.12, 2.50) | 1.27 (0.81, 2.00) |

| 11–20 | 321 | 38 | 1.48 (1.05, 2.10) | 1.47 (1.01, 2.15) |

| >20 | 907 | 109 | 1.51 (1.22, 1.87) | 1.52 (1.18, 1.95) |

| Number of cigarettes smoked per day | ||||

| 1–5 | 387 | 47 | 1.52 (1.11, 2.08) | 1.46 (1.05, 2.05) |

| 6–10 | 496 | 62 | 1.57 (1.19, 2.06) | 1.52 (1.12, 2.07) |

| 11–20 | 429 | 43 | 1.26 (0.91, 1.74) | 1.09 (0.75, 1.57) |

| >20 | 151 | 22 | 1.83 (1.16, 2.88) | 1.85 (1.13, 3.06) |

Adjusting for socio-economic factors, including gender, age, education attainment, household income, living space and number of bedrooms per person.

Table 4.

The association between chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) and second-hand tobacco smoke (SHS)

| Non-CRS | CRS | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR (95% CI)* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of smokers living or working with you | ||||

| 0 | 6042 | 475 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 | 2729 | 273 | 1.27 (1.09, 1.49) | 1.21 (1.03, 1.43) |

| 2 | 572 | 51 | 1.13 (0.84, 1.53) | 1.07 (0.78, 1.48) |

| 3 or above | 395 | 45 | 1.45 (1.05, 2.00) | 1.11 (0.77, 1.60) |

| Years of SHS exposure | ||||

| 1–5 | 729 | 65 | 1.13 (0.87, 1.49) | 0.95 (0.70, 1.29) |

| 6–10 | 814 | 72 | 1.13 (0.87, 1.47) | 1.04 (0.79, 1.36) |

| >10 | 1922 | 198 | 1.31 (1.10, 1.56) | 1.25 (1.03, 1.50) |

| Hours of SHS exposure per week | ||||

| 1–9 | 2646 | 261 | 1.25 (1.07, 1.47) | 0.90 (0.43, 1.89) |

| 10–39 | 565 | 59 | 1.33 (1.00, 1.76) | 1.02 (0.50, 2.08) |

| 40 | 112 | 11 | 1.25 (0.67, 2.33) | 1.21 (0.62, 2.37) |

Adjusted for active smoking status and socio-economic factors, including gender, age, education attainment, household income, living space and number of bedrooms per person.

Discussion

In contrast to the abundant literature about the microbiology, pathophysiology, diagnosis and treatment of CRS, there are relatively rare studies of its prevalence. This is the first large-scale investigation of the epidemiology of CRS in China. The comparability of the structures of gender, age group and education level between the sample and the 2011 national census data and the consistency between the crude prevalence and the age- and gender-adjusted prevalence indicate that the participants were a good nationally representative random sample of urban Chinese. This investigation estimated an 8.0% prevalence of CRS in the entire population and an 8.2% prevalence among adults aged 15–75 years, which are greater than the prevalences in Sao Paul, Korea and Canada (11–13) but lower than the levels of 10.9% in Europe (10) and 12% in the USA (14). Consistently, the National Heath Survey data from the USA revealed that CRS was less prevalent in Asian than in African Americans and Whites (20). Based on the prevalence of 8%, we estimate that approximately 107 million persons are suffering from CRS in mainland China. Due to recurrent symptoms, many patients presenting with CRS require repeated medical treatment and even surgical interventions. The 851 persons with CRS in this study had, on average, visited physicians three times and missed 11 days of work or school due to nasal problems during the last year. These findings suggest an immense economic burden of CRS due to direct medical care costs and productivity losses in mainland China. On the other hand, over half (52.4%) of subjects with symptoms of CRS did not visit any physician because of their nasal problems in the previous year, indicating a problem of healthcare utilization of CRS in mainland China.

Chronic sinusitis exhibited some geographic variation across the seven cities (range 4.8–9.7%) with the lowest prevalence in Beijing where allergic rhinitis was least common among eleven Chinese cities, and the majority of these cities were included in this study (21). However, the variation was much smaller than that reported in the European international survey (range 6.9–27.1%) (10) likely due to the relatively homogeneous racial populations and average economic statuses of the centres in our study. We speculate that geographic variations may exist at finer levels of geography (e.g. district or community). However, we did not make such comparisons due to the limited cases in a single district/community. Interestingly, we demonstrated that CRS was more prevalent in males, which is consistent with the results of another Asia study in Korea (12) but contrasts the findings from western countries (10,13,14). This controversy might be partially because gender differences in the perception of CRS-related symptoms and lifestyles vary between the East and West. Further studies on the prevalence of clinically diagnosed CRS would help to clarify this issue. The literature also reveals inconsistencies in the differences between age groups. A relatively higher prevalence was seen in those aged 15–34 in this study. Kim et al. (12) demonstrated that CRS is more prevalent in old people. A decline of CRS with age was observed in a European survey, and a Canadian survey showed that the prevalence increased with age and levelled off after the age of 60 years (13).

Ethnicity was found to be another factor that was related to CRS. The housing situations and living and dietary habits of ethnic minorities are substantially different from those of the Han. Further studies are required to determine which specific key factors are conductive to a higher incidence of CRS among minorities. A U.S. survey also showed significant differences in CRS prevalence and healthcare use across racial and ethnic categories (20).

Although a few studies suggest that CRS is more prevalent in people with low socio-economic status (12,16), we did not observe a clear trend of enhanced prevalence with higher education. We found people with high school diplomas had a higher prevalence of CRS than other groups. The presence of CRS was not significantly associated with housing area, number of bedrooms or household income. However, low incomes have been associated with higher prevalences of CRS in Canada and Sao Paulo (11,13).

Some data have demonstrated that CRS frequently coexists with asthma, allergic rhinitis and nasal polyps (22,23). We have shown that CRS was more prevalent in the patients with asthma allergic rhinitis and nasal polyps and those with COPD and gout.

Smoking has been associated with upper and lower respiratory tract infections in a number of previous studies (24–27). However, the effects of tobacco smoke on CRS are less well documented. Associations between clinical features, CRS outcomes and smoking have been observed in patients who have undergone functional endoscopic sinus surgery (28–32). In this study, we found that tobacco smoking was associated with a significantly increased risk of CRS. Furthermore, we provided clear evidence that the negative effect generally increased with the duration and dose of smoking. The significantly increased risks associated with second-hand smoke exposure also support the effects of smoking. Although there are differences in the composition of second-hand and mainstream cigarette smoke, and the doses that passive smokers receive are much lower than active smokers’, there are numerous lines of evidence that support the health effects of second-hand smoke (33). We observed a trend towards the effects of second-hand smoke exposure increasing with the duration and dose, although this effect was not statistically significant for some subgroups likely due to the limited power of the stratified analyses for the detection of a relatively weak effect. Further studies of larger scales are needed to characterize the effects of second-hand smoke.

There are some limitations associated with this study. First, the self-reported data might be challenged to some extent. Questionnaire-based and clinical-based diagnoses of CRS have exhibited some discrepancies (34). Specifically, for small children, the questionnaires were completed by their parents, and their CRS-related symptoms might not have been accurately perceived and reported by the parents, which would have led to bias in the estimation of the prevalence in children. Second, although CRS was defined based on symptoms in the last 12 months, the survey was not performed at the same time in all centres, which might have caused some biases in the comparisons of the prevalences between centres due to seasonal variations in CRS. Lastly, CRS can be subdivided into CRSwNP and CRSsNP. According to the EP3OS, CRSwNP and CRSsNP should be defined by clinical criteria supported with endoscopy. In the present study, we identified NP by simply asking the subject whether he or she has been told by a doctor that he or she had NP, leading to a potential underestimate of CRSsNP. We did not compare the characteristics between CRSwNP and CRSsNP because of the limited and biased number of CRSsNP. Further studies are required to determine separately the prevalence and associated risk factors of these two subsets of CRS.

In conclusion, CRS is a common respiratory disease with an estimated prevalence of 8%, which corresponds to 107 million sufferers in mainland China. The present study contributes new evidence about the prevalence of CRS and its social–demographic correlates to the literature. These findings might facilitate people's understanding of the epidemiology of CRS and provide important information for the assessment of the economic burden of CRS and the development and promotion of public health policies associated with CRS.

Acknowledgments

We thank Bachert C and Zhang N from the Upper Airways Research Laboratory, Department of Oto-Rhino-Laryngology, Ghent University Hospital for their kindly providing of the GALEN questionnaire. We also thank Wang Y, Chen J J, Lin L and Cui T for their assistance in data collection.

Funding

This study was supported by grants from the Industry Foundation of the Ministry of Health of China (201202005), NCET-13-0608 and NSFC (81322012, 81373174, 81170896, 81272062, 81273212 and 81471832).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Author contributions

GX, JS and QF initiated this study. CO, HZ, LC, YJW, DZ, WL, SL, PL, LL, YW, JC and TC were principal investigators for the centres and contributed to data collection. CO analysed the data. All authors interpreted the data. CO, JS and QF wrote the manuscript with input from all authors.

References

- 1.Fokkens WJ, Lund VJ, Mullol J, Bachert C, Alobid I, Baroody F, et al. European position paper on rhinosinusitis and nasal polyps. Rhinol Suppl. 2012;2012:1–298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dietz DLD, Hopkins C, Fokkens WJ. Symptoms in chronic rhinosinusitis with and without nasal polyps. Laryngoscope. 2013;123:57–63. doi: 10.1002/lary.23671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bhattacharyya N, Orlandi RR, Grebner J, Martinson M. Cost burden of chronic rhinosinusitis: a claims-based study. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011;144:440–445. doi: 10.1177/0194599810391852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lange B, Holst R, Thilsing T, Baelum J, Kjeldsen A. Quality of life and associated factors in persons with Chronic Rhinosinusitis in the general population. Clin Otolaryngol. 2013;38:474–480. doi: 10.1111/coa.12189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shah A. Allergic rhinitis, chronic rhinosinusitis and nasal polyposis in Asia Pacific: impact on quality of life and sleep. Asia Pac Allergy. 2014;4:131–133. doi: 10.5415/apallergy.2014.4.3.131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ek A, Middelveld RJ, Bertilsson H, Bjerg A, Ekerljung L, Malinovschi A, et al. Chronic rhinosinusitis in asthma is a negative predictor of quality of life: results from the Swedish GA(2)LEN survey. Allergy. 2013;68:1314–1321. doi: 10.1111/all.12222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eweiss AZ, Lund VJ, Barlow J, Rose G. Do patients with chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps suffer with facial pain? Rhinology. 2013;51:231–235. doi: 10.4193/Rhino12.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fokkens W, Lund V, Mullol J. European position paper on rhinosinusitis and nasal polyps. Rhinol Suppl. 2007;2007:1–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tomassen P, Newson RB, Hoffmans R, Lotvall J, Cardell LO, Gunnbjornsdottir M, et al. Reliability of EP3OS symptom criteria and nasal endoscopy in the assessment of chronic rhinosinusitis–a GA(2) LEN study. Allergy. 2011;66:556–561. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2010.02503.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hastan D, Fokkens WJ, Bachert C, Newson RB, Bislimovska J, Bockelbrink A, et al. Chronic rhinosinusitis in Europe–an underestimated disease. A GA(2)LEN study. Allergy. 2011;66:1216–1223. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2011.02646.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pilan RR, Pinna FR, Bezerra TF, Mori RL, Padua FG, Bento RF, et al. Prevalence of chronic rhinosinusitis in Sao Paulo. Rhinology. 2012;50:129–138. doi: 10.4193/Rhino11.256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim YS, Kim NH, Seong SY, Kim KR, Lee GB, Kim KS. Prevalence and risk factors of chronic rhinosinusitis in Korea. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2011;25:117–121. doi: 10.2500/ajra.2011.25.3630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen Y, Dales R, Lin M. The epidemiology of chronic rhinosinusitis in Canadians. Laryngoscope. 2003;113:1199–1205. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200307000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blackwell DL, Lucas JW, Clarke TC. Summary health statistics for U.S. adults: national health interview survey, 2012. Vital Health Stat. 2014;10:1–161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anand VK. Epidemiology and economic impact of rhinosinusitis. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol Suppl. 2004;193:3–5. doi: 10.1177/00034894041130s502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thilsing T, Rasmussen J, Lange B, Kjeldsen AD, Al-Kalemji A, Baelum J. Chronic rhinosinusitis and occupational risk factors among 20- to 75-year-old Danes-A GA(2) LEN-based study. Am J Ind Med. 2012;55:1037–1043. doi: 10.1002/ajim.22074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blackwell DL, Collins JG, Coles R. Summary health statistics for U.S. adults: National Health Interview Survey, 1997. Vital Health Stat. 2002;10:1–109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pleis JR, Lethbridge-Cejku M. Summary health statistics for U.S. adults: National Health Interview Survey, 2006. Vital Health Stat. 2007;10:1–153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fokkens W, Lund V, Bachert C, Clement P, Helllings P, Holmstrom M, et al. EAACI position paper on rhinosinusitis and nasal polyps executive summary. Allergy. 2005;60:583–601. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2005.00830.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Soler ZM, Mace JC, Litvack JR, Smith TL. Chronic rhinosinusitis, race, and ethnicity. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2012;26:110–116. doi: 10.2500/ajra.2012.26.3741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang L, Han D, Huang D, Wu Y, Dong Z, Xu G, et al. Prevalence of self-reported allergic rhinitis in eleven major cities in china. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2009;149:47–57. doi: 10.1159/000176306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jarvis D, Newson R, Lotvall J, Hastan D, Tomassen P, Keil T, et al. Asthma in adults and its association with chronic rhinosinusitis: the GA2LEN survey in Europe. Allergy. 2012;67:91–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2011.02709.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yoshimura K, Kawata R, Haruna S, Moriyama H, Hirakawa K, Fujieda S, et al. Clinical epidemiological study of 553 patients with chronic rhinosinusitis in Japan. Allergol Int. 2011;60:491–496. doi: 10.2332/allergolint.10-OA-0234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee PN. Summary of the epidemiological evidence relating snus to health. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2011;59:197–214. doi: 10.1016/j.yrtph.2010.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bedolla-Barajas M, Morales-Romero J, Robles-Figueroa M, Fregoso-Fregoso M. Asthma in late adolescents of Western Mexico: prevalence and associated factors. Arch Bronconeumol. 2013;49:47–53. doi: 10.1016/j.arbres.2012.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mohammad Y, Shaaban R, Al-Zahab BA, Khaltaev N, Bousquet J, Dubaybo B. Impact of active and passive smoking as risk factors for asthma and COPD in women presenting to primary care in Syria: first report by the WHO-GARD survey group. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2013;8:473–482. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S50551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Benninger MS. The impact of cigarette smoking and environmental tobacco smoke on nasal and sinus disease: a review of the literature. Am J Rhinol. 1999;13:435–438. doi: 10.2500/105065899781329683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Houser SM, Keen KJ. The role of allergy and smoking in chronic rhinosinusitis and polyposis. Laryngoscope. 2008;118:1521–1527. doi: 10.1097/MLG.0b013e31817d01b8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reh DD, Higgins TS, Smith TL. Impact of tobacco smoke on chronic rhinosinusitis: a review of the literature. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2012;2:362–369. doi: 10.1002/alr.21054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Uhliarova B, Adamkov M, Svec M, Calkovska A. The effect of smoking on CT score, bacterial colonization and distribution of inflammatory cells in the upper airways of patients with chronic rhinosinusitis. Inhal Toxicol. 2014;26:419–425. doi: 10.3109/08958378.2014.910284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Briggs RD, Wright ST, Cordes S, Calhoun KH. Smoking in chronic rhinosinusitis: a predictor of poor long-term outcome after endoscopic sinus surgery. Laryngoscope. 2004;114:126–128. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200401000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Berania I, Endam LM, Filali-Mouhim A, Boisvert P, Boulet LP, Bosse Y, et al. Active smoking status in chronic rhinosinusitis is associated with higher serum markers of inflammation and lower serum eosinophilia. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2014;4:347–352. doi: 10.1002/alr.21289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reardon JZ. Environmental tobacco smoke: respiratory and other health effects. Clin Chest Med. 2007;28:559–573. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2007.06.006. vi. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lange B, Thilsing T, Baelum J, Holst R, Kjeldsen A. Diagnosing chronic rhinosinusitis: comparing questionnaire-based and clinical-based diagnosis. Rhinology. 2013;51:128–136. doi: 10.4193/Rhino12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]