Abstract

A novel fabrication method for stretchable magnetoresistive sensors is introduced, which allows the transfer of a complex microsensor systems prepared on common rigid donor substrates to prestretched elastomeric membranes in a single step. This direct transfer printing method boosts the fabrication potential of stretchable magnetoelectronics in terms of miniaturization and level of complexity, and provides strain‐invariant sensors up to 30% tensile deformation.

Keywords: giant magnetoresistive multilayers, giant magnetoresistive sensors, stretchable electronics, stretchable magnetoelectronics, transfer printing

Stretchable electronics1, 2 is one of the most vital technological research fields of the latest years, aiming to revolutionize custom electronic systems toward being arbitrarily reshapeable on demand after their fabrication. This opens up novel application potentials for multifunctional high‐speed electronic systems like smart skins,3, 4 active medical implants,5, 6 soft robotics,7, 8 or stretchable consumer electronics.9, 10 A variety of functional components that can be subjected to high tensile deformations have already been introduced, including light emitting diodes,11 solar cells,10 pressure and temperature sensors,12 integrated circuitry,13 batteries,14, 15 antennas,16 and many more. Introducing stretchable highly sensitive magnetosensorics into the family of stretchable electronics17 was envisioned to equip this novel electronic platform with magnetic functionalities. This can be of particular interest for smart skin and biomedical applications promoted by very recent developments of imperceptible12 and transient6 electronics, as magnetoelectronic components can add a sense of orientation, displacement, and touchless interaction.

All approaches to stretchable magnetoelectronics17, 18, 19, 20 rely on the direct deposition of magnetic multilayers onto elastomeric poly(dimethylsiloxane) (PDMS) membranes, which are thermally prestrained in order to induce wrinkling. This method, although it allowed the first stretchable magnetic field sensorics to be fabricated,17 is associated with severe process limitations, preventing significant advances in performance and level of complexity and thus, restricting the applicability of the technology. First of all, multiple patterning steps, which are absolutely necessary for the integration of magnetoelectronic components into multifunctional stretchable electronics platforms, can hardly be realized reliably on PDMS. Another crucial aspect is related to the limited stretchability of the functional elements relying on wrinkling due to thermally induced prestrain. Indeed, stretchabilities of a few percent only18, 20 can be achieved, unless cracking of the sensing layer is permitted.19 However, stretching due to crack formation is applicable only for functional elements that are much larger than the cracks and hence, this approach contradicts the device miniaturization, which is highly relevant especially for wearable navigation and orientation systems, some biomedical applications1, 21, 22 or for the fine mapping of inhomogeneous magnetic fields and textures. These severe drawbacks call for a novel fabrication strategy of stretchable magnetoelectronic devices that allows for smaller structures and mechanically induced prestrain. Transfer printing23 has evolved to one of the most promising techniques for stretchable devices.24, 25 This method relies on a micropatterned stamp that picks up structures from a donor substrate and releases them on a receiving surface in a two‐step process.

Here, we successfully demonstrate a direct single‐step transfer printing of highly sensitive and miniaturized magnetic field sensorics relying on the giant magnetoresistive (GMR) effect. The developed strategy allows for a transfer of GMR systems with a size down to 6 μm from standard rigid substrates to an elastomeric membrane in a single step, without requiring micropatterned stamps. With the preparation of entire magnetoelectric sensor systems with electrical contacts on silicon wafers, the full potential of state‐of‐the‐art microfabrication methods and thin‐film technologies can be exploited. The latter allows a level of complexity to be reached that is not met when the magnetic layer stack is directly deposited onto elastomeric membranes. Another advantage of this approach is that the direction of the prestrain can be controlled in order to achieve either uniaxial or biaxial stretchability. As a receiver, we chose 60 μm thick PDMS membranes that are prestretched by mechanical means up to about 25% × 25% strain. Similar to pioneering works by Jones et al.,26 mechanical prestretching imposes higher wrinkling amplitudes compared with the thermally prestrained case,27, 28 which is beneficial to achieve higher stretchabilities without inducing cracks in the functional magnetic layer. Additionally, the advanced microfabrication potential allows combination with compliant meander geometries.29, 30 With this new approach, we achieve an increase in the stretchability of the GMR multilayer sensors from about 4%17, 18, 20 up to 30% without relying on the formation of cracks. The latter is of great importance as the senor elements introduced here are truly strain invariant since without cracks almost no resistance change is associated with the tensile deformation.

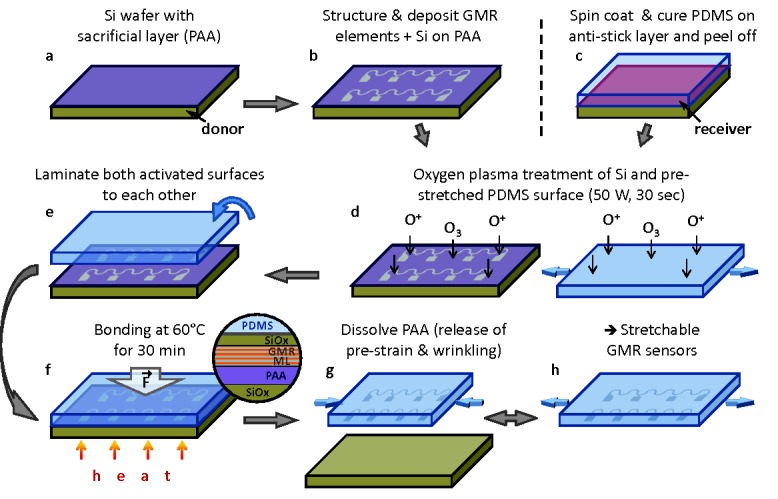

Figure 1 shows the process flow of the direct transfer method introduced here (details are provided in the methods section). The key aspect is the choice of the sacrificial layer on top of the rigid substrate. For this purpose, we chose Ca2+ metal cross‐linked poly(acrylic acid) (PAA) with a total thickness of only 80 nm (Figure 1a) fulfilling all crucial requirements to the sacrificial layer.31 Indeed, it provides a very small surface roughness of below 1 nm (see Figure S1, Supporting Information), which is necessary for the successful growth of the high‐performance magnetic sensor layer. Furthermore, the metal cross‐linked PAA possesses high molecular weight (>400 K) and is chemically inert to standard microelectronic processing based on photoresists. In combination with the excellent temperature stability of up to 150 °C, the latter provides the possibility for multiple lift‐off lithography steps, as required for sensor integration purposes. The Ca2+ metal cross‐linked PAA is dissolvable only in strong alkaline (pH > 10), acidic (pH < 2), or chelating (a solution of polydentate molecules like ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, EDTA) solvents.

Figure 1.

Process flow of the direct transfer of magnetoelectronic nanomembranes. a,b) Preparation of GMR multilayers with Si capping layer on a PAA‐coated Si wafer (donor). c) Spin coating and curing of a PDMS film (receiver) on an antistick layer‐coated carrier. d) Oxygen plasma activation of donor and prestretched receiver substrate. e,f) Heat and pressure‐assisted adhesion of both activated surfaces. The magnified view in (f) shows a cross section of the bonding interface region. The bonding is established between the top Si surface, which is oxidized to SiOx by the plasma and the activated PDMS (layers not drawn to scale). g) Dissolving of the PAA sacrificial layer to detach the GMR structures from the donor substrate and release of the prestrain in the receiver membrane to obtain a wrinkled morphology. h) The transferred sensors can be elastically stretched in the direction of the prestrain.

The PAA‐coated Si wafer is used as the donor substrate to fabricate GMR multilayer sensor elements, which are lithographically patterned to different sizes (down to 6 μm width) and different shapes (stripes and meanders) (Figure 1b). The advantage of using the meander‐shaped sensorics is twofold: i) this shape allows the resistance of the sensor element to be increased, which is beneficial from the signal acquisition point of view and ii) they allow for an enhanced stretchability compared with the stripe‐shaped metal layers.20, 29 On top of the GMR layer stack, a 4 nm Si layer is deposited, which provides the plasma‐induced adhesion to the receiving PDMS membrane. The freestanding PDMS receiver is prepared by spin coating and peeling it from the support after cross linking (Figure 1c). The elastomeric membrane of 60 μm thickness is prestretched and fixed to a holding frame (see Figure S2, Supporting Information), before it undergoes an oxygen plasma treatment together with the Si‐coated sensors on the donor substrate (Figure 1d). The plasma activates both, the PDMS silicon rubber surface and the naturally oxidized thin silicon film on top of the sensor surface, which allows for a strong covalent bonding to each other upon contact (Figure 1e). The adhesion is promoted by thermal and mechanical means (see Experimental Section), after the uniaxially or biaxially prestretched PDMS membrane was flipped onto the activated surface of the donor substrate (Figure 1f). To finalize the transfer, the PDMS membrane is released from the holding frame and the sacrificial layer is dissolved in an aqueous solution of EDTA. This smoothly detaches the donor substrate from the receiving membrane and simultaneously releases the mechanically induced prestrain, which leads to a wrinkling of the transferred structures on the PDMS membrane (Figure 1g). The wrinkled sensor elements on the soft support can be elastically stretched according to the induced prestrain (Figure 1h).

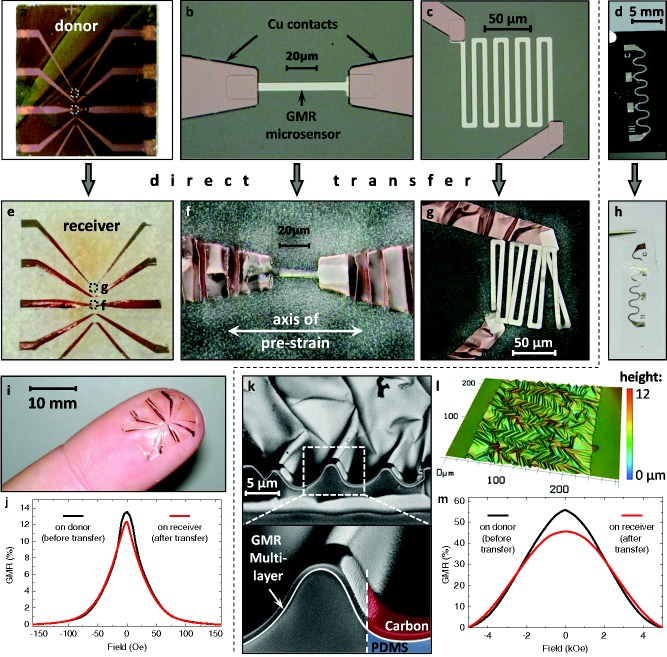

Two different sensor designs were prepared in this study to highlight the two main features, namely enhanced level of complexity and increased stretchability, enabled by the introduced transfer process. The first layout is an array of microsized GMR sensors with electrical contacting, which requires two‐step lithography to be performed (Figure 2 a). The microsensor array consists of five differently shaped GMR multilayer elements, all of 6 μm width, and a copper electrode structure for reliable contacting. Two of the sensor elements, a stripe and a meander, are displayed in Figure 2b,c, respectively. Further details on the entire array can be found in the Supporting Information Figure S3. Since microsensor arrays are mainly used to detect spatially confined and small magnetic fields in the range of several Oersteds only,21 the sensing elements in this case consist of highly sensitive GMR [Py/Cu]30 multilayers coupled on the 2nd anti‐ferromagnetic maximum.32 The possibility to perform two‐step lithography in a standard way demonstrates the enhanced fabrication potential in terms of miniaturization and complexity compared with previous approaches to stretchable magnetoelectronics.17, 18, 20 The second sensor design is a macroscopic serpentine meander equipped with contact pads for reliable magnetoelectronic characterization in a four‐point configuration (Figure 2d). Here, we chose [Co/Cu]50 GMR multilayers, well known for their notorious GMR magnitude. A sketch of the used meander pattern and its dimensions is provided in Figure S4 (Supporting Information). This kind of meanders have been shown to enhance the stretchability of GMR multilayers grown onto PDMS substrates.20 Hence, we will apply this type of sensor to demonstrate the increased stretchability achieved using the direct transfer printing method. Its larger size is beneficial for performing stretching experiments as the evaluation of strain on the magnetosensitive elements and its influence on their sensing behavior is more meaningful than for microscopic sensors.

Figure 2.

Direct transfer of two sensor designs (respective panels are separated by the dashed line): a) A GMR microsensor array of different [Py/Cu]30 multilayer elements on the rigid donor substrate. The magnified views in (b,c) show a microsensor stripe and meander, respectively, with the two‐step photolithography for the sensing element and the electrodes. d) A macroscopic serpentine meander consisting of a [Co/Cu]50 GMR multilayer. e–g) Microsensors transferred to the receiving substrate using a uniaxial prestrain of 20%, as indicated in (f). h) The serpentine meander after transfer to the free‐standing PDMS membrane using a biaxial prestrain of 25% × 25%. i) The transferred microsensor array can conform to the soft and curved surface of a fingertip. j) GMR characteristics of a microsensor element before (black) and after (red) the transfer process. k) SEM images of a FIB cut through the transferred GMR film in (h) showing the good adhesion of the wrinkled magnetic nanomembrane to the PDMS support. l) A confocal microscopy image showing the topology of the wrinkled GMR multilayer element in (h). m) GMR characteristics of the serpentine meander before (black) and after (red) the transfer process.

Figure 2e–h shows the same structures as above, respectively, after the transfer to the receiving PDMS membrane. For the microsensor array, a uniaxial prestrain of 20% along the sensor stripes was used, as indicated in Figure 2f. In the case of uniaxial prestrain, the transverse direction has to be prestretched as well, in order to compensate for the Poisson's contraction, avoiding the destruction of transferred structures upon strain release. The final sensor array can be applied to any curved or soft surfaces, as demonstrated in Figure 2i with the GMR microsensors situated on a fingertip. The functionality of the transferred sensors is proven by GMR measurements of one element before (black) and after (red) the transfer process (Figure 2j). The GMR ratio is defined as the magnetic field dependent change of the resistance, R(H ext), normalized to the value of resistance when the sample is magnetically saturated, R sat: GMR(H ext) = [R(H ext) – R sat]/R sat. Both curves show a similar GMR signal at small magnetic fields.

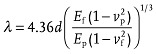

The serpentine meander is transferred with a biaxial prestrain of 25% × 25%. The good adhesion of the plasma induced bonding between the GMR multilayer and the PDMS membrane is demonstrated by means of a scanning electron microscopy (SEM) investigation of the sample cross section (Figure 2k). The cross section was prepared using a focused ion beam (FIB) etching through the wrinkled magnetic nanomembrane. The images show that the GMR multilayer is firmly attached to the soft PDMS, even throughout the wrinkles. A confocal microscopy image of the serpentine surface is included in Figure 2l showing the wrinkled morphology with an amplitude of ≈2.5 μm and a period of ≈11.7 μm. The wrinkling period of the magnetic nanomembrane on PDMS can be theoretically assessed using a model suggested by Bowden et al.,27 given in Equation (1):

|

(1) |

Here, E p,f and ν p,f denote the Young's modulus and Poisson's ratio of the rigid film (f) and the soft polymer (p), respectively. We approximate the mechanical parameters of the [Co/Cu]50 GMR layer (including the 4 nm plasma‐oxidized silicon layer, having a total thickness of 115 nm) from their bulk values weighted by their composition based on the layer thicknesses to be E f = 164 GPa and ν f = 0.32 (see Supporting Information). The respective values for the PDMS support are retrieved from a stress–strain measurement found elsewhere.17 This results in a wrinkling period according to Equation (1) of λ = 22.3 μm. This value, however, gives only the period of the wrinkles upon their formation and has to be corrected for the compressive deformation of the rubber support upon relaxation, which pushes together the buckles accordingly. For the chosen prestrain of 25% along one direction, there is a resulting compression of 0.2, which shrinks the calculated wrinkling period to λ = 17.8 μm. The somewhat smaller value that is observed experimentally may be due to the O2 plasma treatment of the PDMS, which results in a surface layer with increased but unknown Young's modulus E p, which is not included in the theoretical reflection.

The magnetoelectrical performance of the [Co/Cu]50 multilayer meander before and after the transfer process is shown in Figure 2m. The transferred GMR element reveals an increased saturation field, which is attributed to the appearance of out‐of‐plane components of the magnetization at the locations of the wrinkle sidewalls perpendicular to the applied magnetic field. This effect becomes pronounced in this sample due to the large amplitude of biaxial wrinkles (amplitude/period = 0.29) compared with the previous reports with rather shallow parallel wrinkles (amplitude/period = 0.03).17 Since the saturation value is beyond the maximum field range of ±5 kOe achievable in the setup, the GMR curve determined in this measurement reaches a value of 46% after the transfer from 57% beforehand.

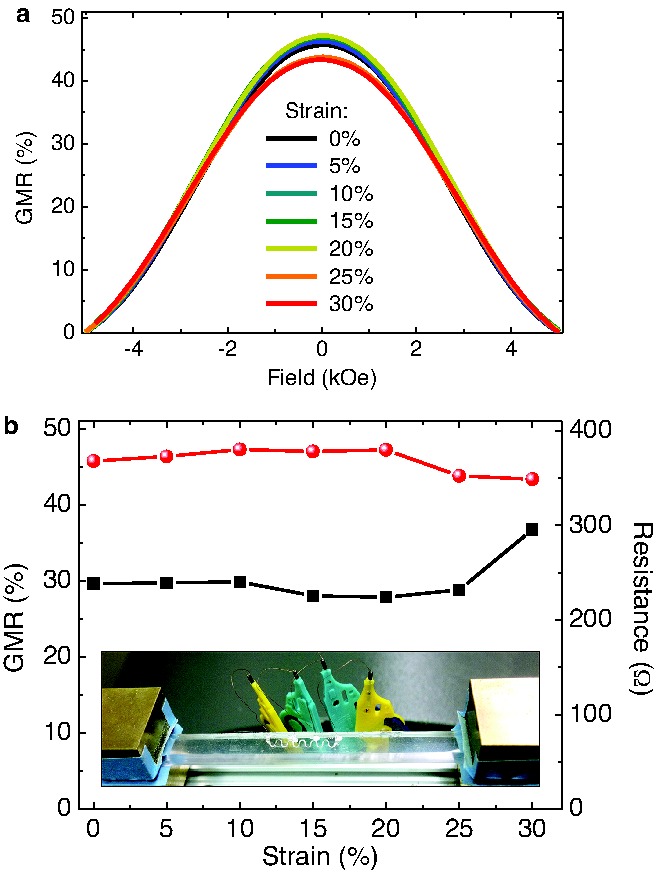

In order to test the stretchability of the transfer‐printed GMR sensor elements, a serpentine meander on elastic PDMS membrane was mounted to a computer‐controlled stretching stage, as shown in the inset of Figure 3 b, that allows for in situ recording of GMR curves as the sample is stretched. For a detailed description of the experimental setup see Figure S5 (Supporting Information). The sensor characteristics is plotted for increasing strains in Figure 3a and shows no significant changes, except for a small drop beyond 20% strain. In Figure 3b, the GMR magnitude and the sensor resistance at zero field is presented in dependence of the applied tensile strain. Both values are subjected to only small changes up to a uniaxial elongation of the sensor of 30%, before the electrical connection is lost. This data presents the compliance and invariance of the prepared magnetic sensing elements to application relevant tensile deformations. Especially the maintained resistance proves that only a very limited number of cracks are induced in the wrinkled GMR nanomembrane as it expands. The obtained stretchability of 30% is attributed to a combination of the wrinkling due to mechanically induced prestrain in the stretching direction (25%) and the additional compliance of the meander pattern (4%).20

Figure 3.

Stretching of transferred [Co/Cu]50 multilayer meanders. a) GMR curves measured at different strains. The GMR ratio is smaller than the known magnetoresistance for [Co/Cu] multilayers, because the saturation field is beyond the maximum field range (±5 kOe) of the setup. b) GMR magnitude (red dots) and sensor resistance (black squares) with increasing tensile strain. The inset shows the sensor mounted to the stretching stage and contacted for in situ GMR characterization.

In conclusion, we have introduced a novel fabrication process for stretchable magnetoelectronics relying on a single‐step direct transfer printing of thin functional elements from a rigid donor substrate to a mechanically prestretched elastic membrane. The detachment of magnetic nanomembranes from the donor substrate is facilitated by means of a PAA‐based sacrificial layer. To assure a good adhesion to the receiving PDMS elastomeric membrane, an oxygen plasma treatment of the capping Si surface of the sensor, on the one hand, and the prestretched PDMS membrane is found to be absolutely crucial. We would like to emphasize that although the individual fabrication steps, e.g., use of sacrificial layers or plasma treatment are already known, the key novelty of the present approach comes from the combination of different processing steps and materials in exactly the right order to obtain a fabrication route that allows for the superior properties of stretchable magnetoelectronics. We demonstrated the fabrication potential of this method in terms of miniaturization and level of complexity by transferring an entire microsensor array including contact structures in a single step. Furthermore, the stretchability of transferred GMR multilayer elements is presented up to strains of about 30% relying solely on the wrinkled topology and the meander geometry, without the formation of cracks. With this result, we reveal a one order of magnitude increase in stretchability of GMR multilayers compared with the current state‐of‐the‐art.20 Both, the GMR characteristic and sensor resistance remain almost unchanged over the entire range of strain, which was not achieved by any other means so far.17, 18 The presented direct transfer approach is not limited to magnetic nanomembranes, which renders possible the combination of magnetoelectronic components with other stretchable functional elements to form smart multifunctional and interactive electronic systems triggered by a magnetic field.

Experimental Section

Preparation of the Poly(acrylic acid) Sacrificial Layer: PAA of M v = 450 000 g mol–1 (Sigma–Aldrich Co. LLC) was dissolved to a concentration of 4% (w/v) in deionized (DI) water at 60 °C in a shaking incubator for 24 h. The resulting solution was diffusively transparent because of higher molecular weight fractions of the PAA. These fractions were separated and removed by centrifugation at 3000 revolutions per minute for 2 h in 25 ml tubes. The transparent PAA solution was then spin coated on the surface of Si wafer substrates at 3500 revolutions per minute for 35 s, resulting in a film thickness of about 80 nm. After spin coating, the substrate was subjected to cross linking in a 1 m solution of CaCl2 (Sigma–Aldrich Co. LLC) in DI water with subsequent rinsing in pure DI water. The prepared substrates were prebaked at 90 °C for 5 min before lithographic processing.

Preparation of Giant Magnetoresistive Multilayer Elements: After preparation of the sacrificial layer, standard lift‐off photolithography techniques were used to pattern GMR sensors on top of PAA. GMR multilayers of Co(1)/[Co(1)/Cu(1.2)]50 (referred to as: [Co/Cu]50) or Py(1.5)/[Py(1.5)/Cu(2.3)]30 (referred to as: [Py/Cu]30), as stated in the text, were deposited using magnetron sputter deposition at room temperature (base pressure: 7.0 × 10−7 mbar; Ar sputter pressure: 9.4 × 10−4 mbar; deposition rate: 2 Å s−1; Py: Ni81Fe19; thicknesses given in nm). The electrode structures for the GMR microsensor arrays were patterned in a second photolithographic step using a mask aligner (MJB4, Karl Suss). Cr(5)/Cu(50) was used as the contacting materials that were deposited by e‐beam evaporation (all thicknesses are given in nm). Subsequently, a layer of 4 nm Si was sputtered on top of the structures.

Direct Transfer Printing: The receiver membranes were prepared by mixing PDMS prepolymer (Sylgard 184, Dow Corning) with the curing agent in a 10:1 ratio and subsequent degassing in a vacuum desiccator. The gel blend was then spin coated onto AZ photoresist‐covered silicon wafers with 1500 revolutions per minute for 30 s. The PDMS films were cured at 90 °C for 1 h on a hot plate, peeled from the rigid handling supports and prestretched as stated in the text using a holding frame with clamps (see Figure S5, Supporting Information). The prepared structure on the donor substrate and the prestretched receiver membrane including the holding frame were placed in a vacuum chamber for oxygen plasma activation at 50 W for 30 s. The thus activated surfaces of donor and receiver were then brought into contact and placed onto a hot plate at 60 °C under a weight adding a pressure of about 10 kPa for 30 min. After releasing the receiver from the holding frame, the sandwiched sensor structure was immersed into a 0.5 m aqueous solution of disodium EDTA (VWR International GmbH) to dissolve the sacrificial layer and release the donor substrate.

Supporting information

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supplementary

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the work of I. Fiering for magnetron sputter depositions and S. Harazim for the maintenance of the clean room facilities (both IFW Dresden). This work was financed in part via the BMBF project Nanett (German Federal Ministry for Education and Research FKZ: 03IS2011 FO) and the European Research Council under the European Union's Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007–2013)/ERC grant agreement n° 306277.

The copyright line for this article was changed on February 19, 2015, after original online publication.

References

- 1. Rogers J. A., Someya T., Huang Y. G., Science 2010, 327, 1603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wagner S., Bauer S., MRS Bull. 2012, 37, 207. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kim D. H., Lu N. S., Ma R., Kim Y. S., Kim R. H., Wang S. D., Wu J., Won S. M., Tao H., Islam A., Yu K. J., Kim T. I., Chowdhury R., Ying M., Xu L. Z., Li M., Chung H. J., Keum H., McCormick M., Liu P., Zhang Y. W., Omenetto F. G., Huang Y. G., Coleman T., Rogers J. A., Science 2011, 333, 838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Webb R. C., Bonifas A. P., Behnaz A., Zhang Y. H., Yu K. J., Cheng H. Y., Shi M. X., Bian Z. G., Liu Z. J., Kim Y. S., Yeo W. H., Park J. S., Song J. Z., Li Y. H., Huang Y. G., Gorbach A. M., Rogers J. A., Nat. Mater. 2013, 12, 938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kim D. H., Lu N. S., Ghaffari R., Kim Y. S., Lee S. P., Xu L. Z., Wu J. A., Kim R. H., Song J. Z., Liu Z. J., Viventi J., de Graff B., Elolampi B., Mansour M., Slepian M. J., Hwang S., Moss J. D., Won S. M., Huang Y. G., Litt B., Rogers J. A., Nat. Mater. 2011, 10, 316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hwang S. W., Tao H., Kim D. H., Cheng H. Y., Song J. K., Rill E., Brenckle M. A., Panilaitis B., Won S. M., Kim Y. S., Song Y. M., Yu K. J., Ameen A., Li R., Su Y. W., Yang M. M., Kaplan D. L., Zakin M. R., Slepian M. J., Huang Y. G., Omenetto F. G., Rogers J. A., Science 2012, 337, 1640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Shepherd R. F., Ilievski F., Choi W., Morin S. A., Stokes A. A., Mazzeo A. D., Chen X., Wang M., Whitesides G. M., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 20400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Martinez R. V., Glavan A. C., Keplinger C., Oyetibo A. I., Whitesides G. M., Adv. Funct. Mater. 2014, 24, 3003. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sekitani T., Nakajima H., Maeda H., Fukushima T., Aida T., Hata K., Someya T., Nat. Mater. 2009, 8, 494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kaltenbrunner M., White M. S., Glowacki E. D., Sekitani T., Someya T., Sariciftci N. S., Bauer S., Nat. Commun. 2012, 3, 770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. White M. S., Kaltenbrunner M., Glowacki E. D., Gutnichenko K., Kettlgruber G., Graz I., Aazou S., Ulbricht C., Egbe D. A. M., Miron M. C., Major Z., Scharber M. C., Sekitani T., Someya T., Bauer S., Sariciftci N. S., Nat. Photonics 2013, 7, 811. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kaltenbrunner M., Sekitani T., Reeder J., Yokota T., Kuribara K., Tokuhara T., Drack M., Schwodiauer R., Graz I., Bauer‐Gogonea S., Bauer S., Someya T., Nature 2013, 499, 458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kim D. H., Ahn J. H., Choi W. M., Kim H. S., Kim T. H., Song J. Z., Huang Y. G. Y., Liu Z. J., Lu C., Rogers J. A., Science 2008, 320, 507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kettlgruber G., Kaltenbrunner M., Siket C. M., Moser R., Graz I. M., Schwodiauer R., Bauer S., J. Mater. Chem. A 2013, 1, 5505. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Xu S., Zhang Y. H., Cho J., Lee J., Huang X., Jia L., Fan J. A., Su Y. W., Su J., Zhang H. G., Cheng H. Y., Lu B. W., Yu C. J., Chuang C., Kim T. I., Song T., Shigeta K., Kang S., Dagdeviren C., Petrov I., Braun P. V., Huang Y. G., Paik U., Rogers J. A., Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 1543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cheng S., Wu Z. G., Lab Chip 2010, 10, 3227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Melzer M., Makarov D., Calvimontes A., Karnaushenko D., Baunack S., Kaltofen R., Mei Y. F., Schmidt O. G., Nano Lett. 2011, 11, 2522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Melzer M., Karnaushenko D., Makarov D., Baraban L., Calvimontes A., Monch I., Kaltofen R., Mei Y. F., Schmidt O. G., RSC Adv. 2012, 2, 2284. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Melzer M., Lin G. G., Makarov D., Schmidt O. G., Adv. Mater. 2012, 24, 6468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Melzer M., Kopylov A., Makarov D., Schmidt O. G., Spin 2013, 3, 6. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hall D. A., Gaster R. S., Lin T., Osterfeld S. J., Han S., Murmann B., Wang S. X., Biosens. Bioelectron. 2010, 25, 2051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Weddemann A., Auge A., Albon C., Wittbracht F., Hutten A., J. Appl. Phys. 2010, 107, 4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Meitl M. A., Zhu Z. T., Kumar V., Lee K. J., Feng X., Huang Y. Y., Adesida I., Nuzzo R. G., Rogers J. A., Nat. Mater. 2006, 5, 33. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chanda D., Shigeta K., Gupta S., Cain T., Carlson A., Mihi A., Baca A. J., Bogart G. R., Braun P., Rogers J. A., Nat. Nanotechnol. 2011, 6, 402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Carlson A., Bowen A. M., Huang Y. G., Nuzzo R. G., Rogers J. A., Adv. Mater. 2012, 24, 5284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Jones J., Lacour S. P., Wagner S., Suo Z. G., J. Vac. Sci. Technol. A 2004, 22, 1723. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bowden N., Brittain S., Evans A. G., Hutchinson J. W., Whitesides G. M., Nature 1998, 393, 146. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Choi W. M., Song J. Z., Khang D. Y., Jiang H. Q., Huang Y. Y., Rogers J. A., Nano Lett. 2007, 7, 1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gray D. S., Tien J., Chen C. S., Adv. Mater. 2004, 16, 393. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Li T., Suo Z. G., Lacour S. P., Wagner S., J. Mater. Res. 2005, 20, 3274. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Linder V., Gates B. D., Ryan D., Parviz B. A., Whitesides G. M., Small 2005, 1, 730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Parkin S. S. P., Annu. Rev. Mater. Sci. 1995, 25, 357. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supplementary