Abstract

The biomarker 8-iso-prostaglandin F2α (8-iso-PGF2α) is regarded as the gold standard for detection of excessive chemical lipid peroxidation in humans. However, biosynthesis of 8-iso-PGF2α via enzymatic lipid peroxidation by prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthases (PGHSs), which are significantly induced in inflammation, could lead to incorrect biomarker interpretation. To resolve the ambiguity with this biomarker, the ratio of 8-iso-PGF2α to prostaglandin F2α (PGF2α) is established as a quantitative measure to distinguish enzymatic from chemical lipid peroxidation in vitro, in animal models, and in humans. Using this method, we find that chemical lipid peroxidation contributes only 3 % to the total 8-iso-PGF2α in the plasma of rats. In contrast, the 8-iso-PGF2α levels in plasma of human males is generated >99% by chemical lipid peroxidation. This establishes the potential for an alternate pathway of biomarker synthesis, and draws into question the source of increases in 8-iso-PGF2α seen in many human diseases. In conclusion, solely measuring increases in 8-iso-PGF2α do not necessarily reflect increases in oxidative stress; therefore, past studies using 8-iso-PGF2α as a marker of oxidative stress may have been misinterpreted. The 8-iso-PGF2α/ PGF2α ratio can be used to distinguish biomarker synthesis pathways and thus confirms the potential change in oxidative stress in the myriad of disease and chemical exposures known to induce 8-iso-PGF2α.

Keywords: F2-isoprostanes, oxidative stress, inflammation, biomarkers, lipid peroxidation

Introduction

An increase in the oxidation of biomolecules, or “oxidative stress”, is believed to be involved in the development of various pathologies, e.g., heart disease [1], diabetes, cancer, Alzheimer's [2], obesity [3], and many more. Validating and measuring an in vivo biomarker that reflects an increase in biomolecule oxidation is a great methodological challenge. Much effort has been undertaken over several decades to establish the best biomarker indicating genuine free radical-mediated, chemical oxidation of biomolecules. The biomolecules showing the most potential are the oxidation products of polyunsaturated fatty acids [4, 5]. A variety of oxidized fatty acids are continuously formed in vivo, and they have profound impacts on cellular biology [6]. These fatty acid oxidation products are formed by both enzymes and chemical lipid peroxidation initiated by a free radical formed on another molecule.

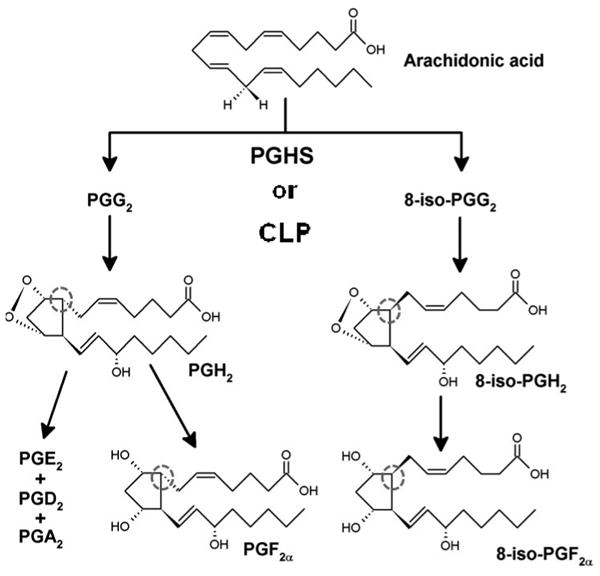

Out of all oxidized fatty acids, the best indicators of oxidative stress in vivo are currently the F2-isoprostanes, specifically 8-iso-prostaglandin F2α (8-iso-PGF2α) [4, 5, 7]. 8-iso-PGF2α has been studied as a biomarker of lipid peroxidation in nearly 500 animal studies and 900 human studies to date and has been found to correlate with a variety of diseases and exposures [8]. 8-iso-PGF2α is distinguished from its enzymatic lipid peroxidation analog (prostaglandin F2α; PGF2α) by the stereochemistry around the carbon at position 8 (Scheme 1) [9]. This distinct stereochemistry is attributed to the lack of stereospecificity associated with the chemical lipid peroxidation of the precursor, arachidonic acid [7, 10-12].

Scheme 1.

The peroxidation of arachidonic acid with the chemical structures of intermediates and products integral to this study.

Attributing the formation of 8-iso-PGF2α solely to chemical lipid peroxidation has been challenged by several investigators [5, 13-19]. Numerous experiments have demonstrated the contribution of prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthases (PGHS-1 & -2) to the formation of 8-iso-PGF2α in vitro, in cells, and in vivo [5, 13-19]. Due to the two formation mechanisms, there is possible ambiguity in the interpretation and validity of measuring 8-iso-PGF2α as a biomarker of oxidative stress. To alleviate the ambiguity associated with this biomarker, we describe and validate a method based on the ratio of 8-iso-PGF2α to PGF2α that can distinguish and quantitate the mechanistic sources of 8-iso-PGF2α in vitro and in vivo.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 1 (Ovine, ≥90 % purity) and 2 (Human Recombinant, ≥70 % purity) were purchased from Cayman (Ann Arbor, MI, USA) and used within 2 weeks of delivery. Enzyme activity was confirmed by an oxygen consumption assay. Arachidonic acid, AAPH, PGH2, 8-iso-PGF2α, PGF2α, PGE2, PGA2, 8-iso-PGF2α-d4, PGF2α-d4, and PGE2-d4 were also purchased from Cayman. Tris-HCl, phenol, porcine hematin, indomethacin, meclofenamic acid, trolox [(±)-6-hydroxy-2,5,7,8-tetramethyl-chromane-2-carboxylic acid], tin (II) chloride dihydrate, diethyl ether, ethanol, and acetic acid were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA).

Sample preparation

PGHS-1 and -2 incubations without reducing agent

PGHSs (40 units) were preincubated with buffer (500 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 1 mM phenol, and 1 μM hematin) for 1 minute at 37 °C. Reactions were initiated by the addition of arachidonic acid (3 μM) and allowed to proceed for 3 minutes. Upon completion of the reaction, an internal standard mix was added and mixed thoroughly. A 150 μL aliquot was removed and extracted twice with 2 mL of diethyl ether. The ether extracts were dried over anhydrous magnesium sulfate. Diethyl ether was evaporated and samples were reconstituted in 100 μL of 33 % ethanol and 0.5 % acetic acid prior to LC/MS/MS analysis. Samples were analyzed immediately after preparation.

PGH2 treatment with reducing agent

To the PGHS incubation buffer, 200 ng of PGH2 was added. Immediately, an internal standard mix and tin (II) chloride (0 – 65 mg/mL of ethanol) was added. A 150 μL aliquot was extracted twice with 2 mL of diethyl ether. Diethyl ether was evaporated and samples were reconstituted in 100 μL of 33 % ethanol and 0.5 % acetic acid prior to LC/MS/MS analysis. Samples were analyzed immediately after preparation.

PGHS-1 and -2 incubations treated with reducing agent

PGHSs (0-50 units) were preincubated with buffer (500 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 1 mM phenol, and 1 μM hematin) for 1 minute at 37 °C. Reactions were initiated by the addition of arachidonic acid (3 μM) and allowed to proceed for 30 seconds (after 30 seconds no additional oxygen uptake was observed). Immediately upon completion of the reaction, an internal standard mix and tin (II) chloride (30 mg/mL ethanol) were added and mixed thoroughly. Continued sample preparation was as described in the previous paragraphs.

PGHS inhibitors and trolox

Inhibitor (meclofenamic acid and indomethacin) and trolox stock solutions were prepared in ethanol, DMSO, and ethanol, respectively. Prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase enzymes (25 units) were preincubated with buffer (500 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 1 mM phenol, 1 μM hematin) + inhibitors or trolox. Reactions were initiated by the addition of arachidonic acid (3 μM) and allowed to proceed for 30 seconds. Immediately upon completion of the reaction, an internal standard mix and tin (II) chloride (30 mg/mL ethanol) were added and mixed thoroughly. Continued sample preparation was as described in the previous paragraphs.

Chemical lipid peroxidation with AAPH

Arachidonic acid in ethanol (10 μg) was dissolved in 1.5 mL of water. To this solution, 2.5 mg of AAPH was added to make a 10 mM solution. The solution was stirred at 37 °C for up to 24 h with frequent sampling. The tube was not sealed to allow a constant supply of oxygen. 100 μL aliquots were removed at designated time points, spiked with internal standard, and extracted with diethyl ether as described previously.

Animals and treatment protocol

Male Fisher 344 rats (260-280 g) were obtained from Charles River Laboratories (Raleigh, NC, USA). Rats were group-housed in a temperature-controlled room at 23–25 °C with a 12/24 h light/dark cycle and allowed free access to food and water. The studies adhered to the National Institutes of Health guidelines for the care and handling of experimental animals. All animal studies were approved by the NIEHS Institutional Review Board. Prior to the study, animals were fasted for 12 h prior to injections. On the day of study, animals (n=4) were anesthetized and blood was drawn through the dorsal aorta with a single draw vacutainer needle (21 gauge) into open vacutainer blood collection tubes containing heparin. Containers were kept on ice until processing.

Volunteer recruitment

Healthy adult male volunteers were recruited to the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences Clinical Research Unit (CRU) in 2014 (n=4). Eligible participants were at least 18 years of age and nonsmokers. Volunteers were asked to donate 10 mL of plasma in one visit. The workup of this plasma was comparable to that described for rats. All study protocols were approved by the NIEHS Institutional Review Board, and all participants gave informed consent prior to providing samples

Plasma sample preparation

Whole blood was centrifuged no more than 30 min after collection (2000 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C) to remove RBCs. Plasma was removed and stored at -80 °C. Prior to analysis, samples were thawed, spiked with internal standards, and kept on ice during sample preparation. 500 μL of rat plasma or 2000 μL of human plasma was subjected to solid phase extraction using 3 mL HLB SPE columns (Waters Corp. Billerica, MA). SPE columns were prewashed with 2 mL of methanol and water. Plasma aliquots were acidified prior to deposition on the column with 0.1 % vol/vol of 1 % acetic acid, 50 % methanol. After loading, samples were washed with 2 mL of a 5 % methanol solution. F2-isoprostanes and prostaglandins were eluted from the column with 2 mL of methanol. Prior to evaporation 6 μL of glycerol was added to each sample. Samples were evaporated in a centrifugal vacuum evaporator maintained at 40 °C. Samples were reconstituted with 50 μL of 33 % ethanol and 0.5 % acetic acid solution.

LC/MS/MS oxylipid analysis

Oxylipid levels were determined by liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectroscopy (LC/MS/MS) as previously described [20, 21]. Online liquid chromatography of extracted in vitro samples was performed with an Agilent 1200 Series capillary HPLC. Separations were achieved using a Halo C18 column (2.7 μm, 100 × 2.1 mm, Advanced Materials Technology, Wilmington, DE, USA), which was held at 50°C. The flow rate was 400 μL/min. Mobile phase A was 0.1% acetic acid in 85:15 water:acetonitrile. Mobile phase B was 0.1% acetic acid in acetonitrile. Gradient elution was used and the mobile phase percent B was varied as follows: 20% B at 0 min, ramp to 40% B from 0 to 5 min, and ramp to 55% B from 5 to 7 min. The injection volume was 10 μL. Samples were analyzed in triplicate. Electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry was used for detection with an AB Sciex API 3000 equipped with a TurboIonSpray source. Plasma samples were run with the same instrumentation and conditions as above or with an UltiMate 3000 RS HPLC system and Quantiva mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific.) Injection volume was adjusted to 10 μL. All analytes were monitored simultaneously as negative ions in a multiple reaction monitoring experiment. Analytes were monitored as parent ion-product ion mass/charge pairs with specific retention times and quantified against standard curves of analytes purchased from Cayman Chemical.

Statistics, data analysis and calculation

One-way analysis of variance was used for statistical analysis. Results are expressed as the mean ± SE. The differences were considered statistically significant when P values were less than 0.05. Error in the ratio was determined by the standard error propagation (Equation 1).

| Equation 1 |

Calculations were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 20.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY).

Peaks identified as 8-iso-PGF2α, PGF2α, or PGE2 were integrated and normalized to their individual deuterated standards: d4-8-iso-PGF2α, d4-PGF2α, and d4-PGE2α. From previously generated quantitation curves, the normalized peak areas were converted to concentrations. The 8-iso-PGF2α / PGF2α ratio was calculated by dividing the concentrations of 8-iso-PGF2α by the concentration of PGF2α.

Results

To quantitate the formation of 8-iso-PGF2α by enzymatic lipid peroxidation, in vitro experiments were first performed with purified PGHS and arachidonic acid. In initial experiments with incubations of purified PGHS-1 or -2, no detectable levels of 8-iso-PGF2α were observed (Figure S1A). The undetectable levels of 8-iso-PGF2α were due to a nearly exclusive generation of PGE2 and other ketone products by spontaneous rearrangement of the endoperoxide intermediates. This does not reflect the in vivo situation where a reducing environment and enzymes increase the levels of F2-prostaglandins and F2-isoprostanes. To better simulate conditions reflecting those found in vivo, an endoperoxide reducing agent, tin (II) chloride, was added after the reaction [22-24]. Addition of tin (II) chloride reduces spontaneous rearrangement of the endoperoxide intermediate PGH2 to PGE2 and increases the reduction of PGH2 to PGF2α (Figure S2) in a dose-dependent manner (Figure S1B). Tin (II) chloride is preferred over other reducing agents such as sodium borohydride as it does not reduce ketones of, e.g., PGE2 (Figure S3).

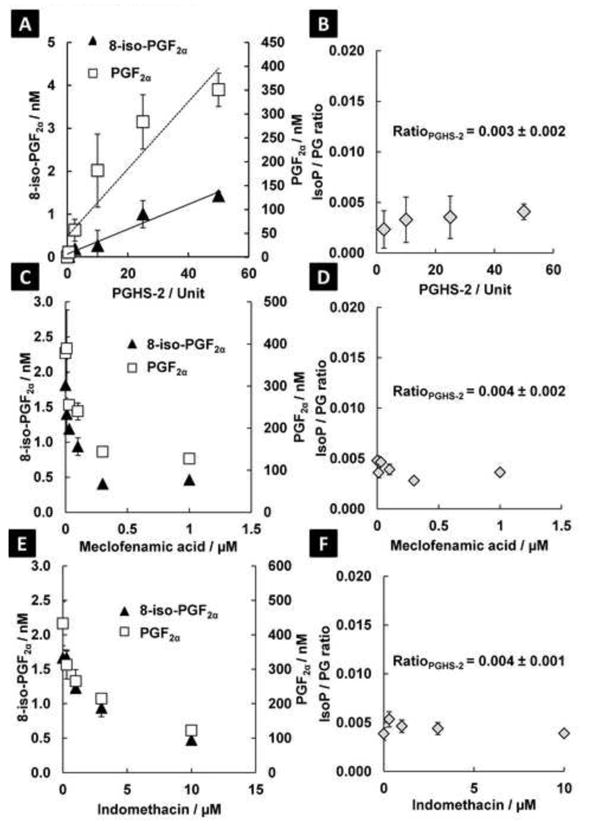

With this methodology, we investigated the formation of 8-iso-PGF2α and PGF2α as well as the 8-iso-PGF2α / PGF2α ratio as formed by PGHS-1 and -2. Linear increases in PGF2α and 8-iso-PGF2α amounts were observed with dependence on PGHS-2 and -1 activity (slope of activity vs. concentration is 12 nM/unit and 0.05 nM/unit for PGF2α and 8-iso-PGF2α, respectively) (Figure 1A & Figure S4A). The 8-iso-PGF2α / PGF2α ratio did not significantly change regardless of enzyme activity [0.008 ± 0.002 for PGHS-1, and 0.003 ± 0.002 for PGHS-2 (Figure 1B & Figure S4B)]. To investigate the robustness of the enzymatic 8-iso-PGF2α / PGF2α ratio, incubations were performed in the presence of classical PGHS inhibitors (meclofenamic acid and indomethacin) and the lipid radical scavenger Trolox (Figure 1C - E & Figure S4C-E). Inhibition of PGHS activities resulted in the expected decrease of the PGF2α and 8-iso-PGF2α amounts. However, the ratio between these two compounds did not change significantly (PGHS-1 = 0.007 ± 0.001 for meclofenamic acid and 0.007 ± 0.002 for indomethacin; PGHS-2 = 0.004 ± 0.002 for meclofenamic acid and 0.004 ± 0.001 for indomethacin) (Figure 1D - F & Figure S4D - F). Trolox (100 μM) did not significantly change the amounts of 8-iso-PGF2α and PGF2α or the ratio (0.006 ± 0.002) when added to PGHS-1 incubations. These results demonstrate that both compounds were formed by PGHS, but formation of PGF2α is favored over 8-iso-PGF2α by >99%. No other F2-isoprostane or prostaglandin (regio)isomers were detected in significant amounts.

Fig. 1. PGHS-2 produces 8-iso-PGF2α at a ratio of 0.004 in relation to PGF2α; this ratio is constant regardless of enzyme activity.

A: The absolute amounts of 8-iso-PGF2α and PGF2α increase linearly with induction of PGHS-2 activity. B: The ratio between the two products does not change significantly. C: The absolute amounts of 8-iso-PGF2α and PGF2α are decreased with inhibition of PGHS-2 enzyme activity by meclofenamic acid (66 and 75% inhibition for PGF2α and 8-iso-PGF2α, respectively). D: The 8-iso-PGF2α / PGF2α ratio is not altered significantly from control with inhibition of PGHS-2 enzyme activity with meclofenamic acid. E: The absolute amounts of 8-iso-PGF2α and PGF2α are decreased with inhibition of PGHS-2 enzyme activity by indomethacin (72% inhibition for both PGF2α and 8-iso-PGF2α). F: The ratio between PGF2α and 8-iso-PGF2α is not altered significantly with inhibition of PGHS-2 enzyme activity with indomethacin.

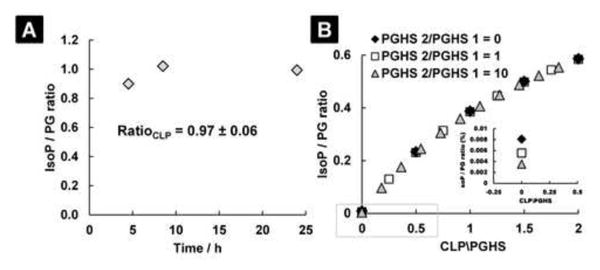

In addition to determining the 8-iso-PGF2α/ PGF2α ratio during enzymatic oxidation, the ratio during chemical lipid peroxidation of arachidonic acid was determined. 8-iso-PGF2α and PGF2α were generated in near equal amounts by 2,2′-azobis-2-methyl-propanimidamide dihydrochloride (AAPH) at 37 °C for 24 h (Figure S5). The 8-iso-PGF2α / PGF2α ratio observed with this water-soluble azo compound that is used as a free radical generator is 0.97 ± 0.06 (Figure 2A). Also, autoxidation of arachidonic acid at 37 °C for 24 and 72 hours showed a similar 8-iso-PGF2α / PGF2α ratio, 0.97 ± 0.09 (Figure S6). The approximate equal production of 8-iso-PGF2α and PGF2α is in contrast to the enzymatic lipid peroxidation, which is >99 % selective for PGF2α. This means that the 8-iso-PGF2α / PGF2α ratio is highly sensitive to chemical lipid peroxidation and could be used to quantitate the relative contributions of both pathways.

Fig. 2. The ratio of 8-iso-PGF2α to PGF2α is a highly sensitive and selective measure of increased chemical lipid peroxidation.

A: Arachidonic acid incubated with the water-soluble free radical generator AAPH produces near equal amounts of 8-iso-PGF2α and PGF2α. B: A mathematical simulation of the 8-iso-PGF2α / PGF2α ratio when chemical lipid peroxidation (CLP) is varied relative to the prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthases (PGHS-1 & PGHS-2). The expression of PGHS-2 is varied in three distinct ratios with respect to PGHS-1 to simulate the effect of enzyme induction on the 8-iso-PGF2α / PGF2α ratio. The equation of this model (Equation 2) can be used to determine the relative contributions of both pathways to the measured 8-iso-PGF2α levels.

From the ratios determined for PGHS and chemical lipid peroxidation, a mathematical model was constructed to distinguish the relative contribution of both pathways to the total 8-iso-PGF2α pool, Figure 2B. To construct the model, the following parameters were used: the 8-iso-PGF2α / PGF2α ratio as generated by PGHS-1 is 0.008 and the expression of PGHS-1 is assumed constant; the 8-iso-PGF2α / PGF2α ratio as generated by PGHS-2 is 0.004; the 8-iso-PGF2α / PGF2α ratio as generated by CLP is 0.97; and the rate of CLP with respect to the rate of enzymatic lipid peroxidation was varied over 2-fold. From the model, it is predicted that the 8-iso-PGF2α / PGF2α ratio will be highly selective for changes in chemical lipid peroxidation. The relative contribution of each pathway to the total 8-iso-PGF2α levels can be calculated by Equation 2 where y = 8-iso-PGF2α / PGF2α ratio and x = CLP/PGHS ratio.

| Equation 2 |

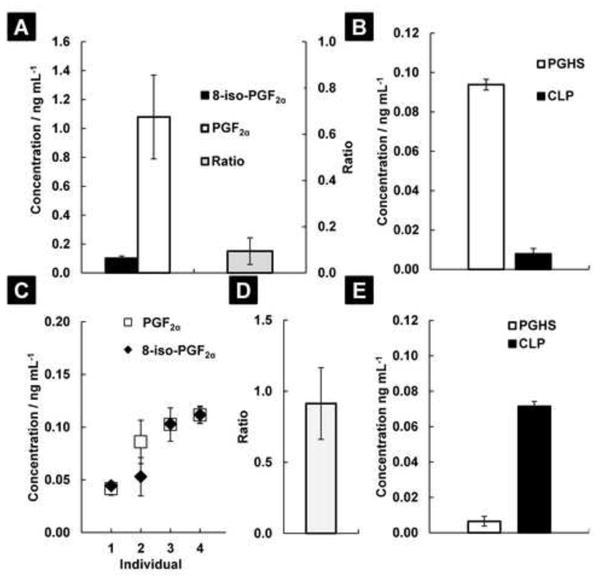

Next, the relative contribution of both enzymatic and chemical lipid peroxidation to the formation of 8-iso-PGF2α was determined in vivo. The 8-iso-PGF2α / PGF2α ratio was measured in plasma of untreated male rats and nonsmoking healthy human males, (Figure 3A, 3C, and 3D). From the mathematical model, the relative contribution of both pathways to the total measured amount of 8-iso-PGF2α can be separated (Figure 3B and 3E). In untreated rats, the contribution of chemical lipid peroxidation to the 8-iso-PGF2α pool is 3.0 ± 1.5 % with and enzymatic contribution of 96.7 ± 1.5 %. Absolute values are compatible to previously published concentrations [5]. In nonsmoking healthy human males, chemical lipid peroxidation is the major contributor to the 8-iso-PGF2α pool, 99.5 ± 0.5 %. Absolute values are compatible to previously published numbers for 8-iso-PGF2α and PGF2α [25]. The mostly enzymatic formation of 8-iso-PGF2α in rats and mostly chemical formation in humans is supported by published reports on the inhibition of 8-iso-PGF2α formation in rats but not in humans by treatment with PGHS inhibitors [5, 18].

Fig 3. 8-iso-PGF2α is mainly a product of enzymatic lipid peroxidation in male fisher 344 rats and mostly of chemical lipid peroxidation in healthy human males.

A: 8-iso-PGF2α and PGF2α were measured in the plasma of 4 untreated rats, and the ratio between the two compounds calculated (Ratiorat plasma = 0.06 ± 0.02; mean ± SE). B: Using Equation 2, at baseline, the source of the measured 8-iso-PGF2α in rat plasma is mainly from PGHS (96.7 ± 1.5 % of total); 3.3 ± 1.5 % comes from chemical lipid peroxidation (CLP). C: 8-iso-PGF2α and PGF2α were measured in the plasma of 4 healthy nonsmoking human males. The levels for each individual are reported as mean ± SE. D: The ratio between 8-iso-PGF2α and PGF2α in human plasma is 0.88 ± 0.26 (mean ± SE). E: Using Equation 2, at baseline, the source of the measured 8-iso-PGF2α in human plasma is mainly from CLP (99.5 ± 0.5 % of total); 0.5 ± 0.5 % comes from PGHSs.

Discussion

Here we have demonstrated a strategy to quantitate and distinguish the source of 8-iso-PGF2α as being from PGHSs or chemical lipid peroxidation. Given the massive induction of PGHS-2 observed in various pathologies (Table S1), we argue that increased expression of PGHS-2 could be a plausible alternate source of increases in 8-iso-PGF2α levels seen in vivo (Table S2). This necessitates reexamination of previous in vivo and human studies concluding increases in oxidative stress from sole measurements of 8-iso-PGF2α.

Arguments raised against the significant contribution of PGHS to 8-iso-PGF2α in vivo levels include the relatively low amount of product formed and the inconsistent and incomplete decreases in 8-iso-PGF2α levels when PGHS inhibitors are used [12, 26]. We have shown here that the absolute amounts of 8-iso-PGF2α and PGF2α generated by both PGHS-1 and -2 are enzyme dependent, but the 8-iso-PGF2α / PGF2α ratio is enzyme independent. Since the total enzymatic activity of PGHSs in vivo is highly variable between organs and disease states (Table S1), it is virtually impossible to determine whether PGHSs contributed significantly to 8-iso-PGF2α levels in vivo without measuring the total enzyme activity [27]. Also, the incomplete inhibition of PGHS-1 and -2 is a highly controversial argument as it is impossible to determine whether 100 % inhibition of PGHS has occurred throughout the entire organism.

It is well recognized that both inflammation and oxidative stress are interconnected, and changes in one can lead to changes in the other [28, 29]. Calculating the 8-iso-PGF2α / PGF2α ratio followed by distinction of the two formation pathways using Equation 2 will allow for both pathways to be measured simultaneously in complex diseases and exposures. In cases where both pathways are altered simultaneously, it will be important to investigate how the pathways are linked and in what order they were affected. The 8-iso-PGF2α / PGF2α ratio should be a highly informative measure during these types of studies.

Several investigators have made observations of the possible contribution of enzymatic lipid peroxidation to the 8-iso-PGF2α pool in various biological systems [5, 13-19]. However, in interpreting the levels of 8-iso-PGF2α as a biomarker of oxidative stress, this “alternate pathway” has been mostly ignored or forgotten in major clinical studies. Our conclusion of chemical lipid peroxidation being the major contributor in healthy human males is somewhat supportive of the myriad of studies already performed with this biomarker. However, the true power of a biomarker is found in its ability to reflect a change between basal/healthy and affected systems. We believe that there will be instances where enzymatic overexpression due to inflammation is the major source 8-iso-PGF2α, whereas in others, the original conclusion of increased oxidative stress due to chemical lipid peroxidation will hold true. Therefore, it is now to imperative reexamine the sources of 8-iso-PGF2α in multiple in vivo models and eventually humans disease that have been shown to increase 8-iso-PGF2α in order to definitively confirm the conclusion of increases in oxidative stress.

Previous studies have identified the major metabolite 15-keto-dihydro-PGF2α (15-K-DH-PGF2α) as a more representative measure of PGF2α formation in vivo [30, 31]. This is mostly due to ex vivo formation of PGF2α during sample acquisition and processing. No artifactual generation of the 15-K-DH-PGF2α has been reported. Given this fact, in future in vivo studies an alternative measure could be the ratio of the metabolites of 8-iso-PGF2α and PGF2α such as the 8-iso-15-keto-dihydro-PGF2α/ 15-keto-dihydro-PGF2α ratio.

In conclusion, regardless of the arguments raised for or against the contribution of enzymes, e.g. PGHSs, to 8-iso-PGF2α levels, there is potential ambiguity in the solely measuring 8-iso-PGF2α and it should therefore be considered inadequate as an index of oxidative stress. Continued disregarding of the potential ambiguity will be of great detriment to the power and legacy of this biomarker. To relieve this ambiguity, the two sources of 8-iso-PGF2α should be quantitatively distinguished. In our opinion, the recommended approach for distinguishing the source of 8-iso-PGF2α is to determine the 8-iso-PGF2α / PGF2α ratio. Determining this ratio requires little added work; in fact, modern mass spectrometric approaches used to measuring 8-iso-PGF2α already detect PGF2α. To apply our method, investigators need only quantify this already detected substance. Determining the 8-iso-PGF2α / PGF2α ratio in conjunction with the calculations described here should unequivocally separate the contributions of both formation mechanisms to the levels of 8-iso-PGF2α in vitro and in vivo. We believe that this new measurement strategy will significantly improve the accuracy and confidence with which oxidative stress is determined in diseases and environmental exposures.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

The gold standard biomarker 8-iso-PGF2α can be formed by two distinct mechanisms.

These two mechanisms should be distinguished prior to concluding an increase in oxidative stress.

A method to make this distinction is measuring the 8-iso-PGF2α/PGF2α ratio.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge Dr. Jason Williams and Dr. Stephanie London for their review of this manuscript and Sandra Chambers for the literature search. We thank the staff of the NIEHS Clinical Research Unit for their help in obtaining human plasma samples. We thank Jean Corbett, Dr. Ann Motten, and Mary Mason for their editorial expertise. This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health and the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences.

Abbreviations

- 8-iso-PGF2α

8-iso-prostaglandin F2α

- PGF2α

prostaglandin F2α

- PGHS

prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase, cyclooxygenase

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Pratico D, Tangirala RK, Rader DJ, Rokach J, FitzGerald GA. Vitamin E suppresses isoprostane generation in vivo and reduces atherosclerosis in ApoE-deficient mice. Nat Med. 1998;4:1189–1192. doi: 10.1038/2685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Keaney JF, Jr, Larson MG, Vasan RS, Wilson PWF, Lipinska I, Corey D, Massaro JM, Sutherland P, Vita JA, Benjamin EJ. Obesity and systemic oxidative stress: clinical correlates of oxidative stress in the Framingham study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23:434–439. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000058402.34138.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murer SB, Aeberli I, Braegger CP, Gittermann M, Hersberger M, Leonard SW, Taylor AW, Traber MG, Zimmermann MB. Antioxidant supplements reduced oxidative stress and stabilized liver function tests but did not reduce inflammation in a randomized controlled trial in obese children and adolescents. J Nutr. 2014;144:193–201. doi: 10.3945/jn.113.185561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kadiiska MB, Gladen BC, Baird DD, Germolec D, Graham LB, Parker CE, Nyska A, Wachsman JT, Ames BN, Basu S, Brot N, Fitzgerald GA, Floyd RA, George M, Heinecke JW, Hatch GE, Hensley K, Lawson JA, Marnett LJ, Morrow JD, Murray DM, Plastaras J, Roberts LJ, II, Rokach J, Shigenaga MK, Sohal RS, Sun J, Tice RR, Van Thiel DH, Wellner D, Walter PB, Tomer KB, Mason RP, Barrett J. Biomarkers of oxidative stress study II: are oxidation products of lipids, proteins, and DNA markers of CCl4 poisoning? Free Radic Biol Med. 2005;38:698–710. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kadiiska MB, Gladen BC, Baird DD, Graham LB, Parker CE, Ames BN, Basu S, Fitzgerald GA, Lawson JA, Marnett LJ, Morrow JD, Murray DM, Plastaras J, Roberts LJ, II, Rokach J, Shigenaga MK, Sun J, Walter PB, Tomer KB, Barrett JC, Mason RP. Biomarkers of oxidative stress study III. Effects of the nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents indomethacin and meclofenamic acid on measurements of oxidative products of lipids in CCl4 poisoning. Free Radic Biol Med. 2005;38:711–718. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Samuelsson B. The Prostaglandins. Angew Chem Int Ed. 1965;4:410–416. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morrow JD, Hill KE, Burk RF, Nammour TM, Badr KF, Roberts LJ., II A series of prostaglandin F2-like compounds are produced in vivo in humans by a non-cyclooxygenase, free radical-catalyzed mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:9383–9387. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.23.9383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Milne GL, Dai Q, Roberts LJ., II The isoprostanes-25 years later. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2015;1851:433–445. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2014.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Milne GL, Sanchez SC, Musiek ES, Morrow JD. Quantification of F2-isoprostanes as a biomarker of oxidative stress. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:221–226. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morrow JD, Harris TM, Roberts LJ., II Noncyclooxygenase oxidative formation of a series of novel prostaglandins: analytical ramifications for measurement of eicosanoids. Anal Biochem. 1990;184:1–10. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(90)90002-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morrow JD, Awad JA, Boss HJ, Blair IA, Roberts LJ., II Non-cyclooxygenase-derived prostanoids (F2-isoprostanes) are formed in situ on phospholipids. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:10721–10725. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.22.10721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roberts LJ, II, Morrow JD. The generation and actions of isoprostanes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1997;1345:121–135. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2760(96)00162-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Watkins MT, Patton GM, Soler HM, Albadawi H, Humphries DE, Evans JE, Kadowaki H. Synthesis of 8-epi-prostaglandin F2α by human endothelial cells: role of prostaglandin H2 synthase. Biochem J. 1999;344:747–754. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Klein T, Reutter F, Schweer H, Seyberth HW, Nusing RM. Generation of the isoprostane 8-epi-prostaglandin F2α in vitro and in vivo via the cyclooxygenases. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997;282:1658–1665. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Favreau F, Petit-Paris I, Hauet T, Dutheil D, Papet Y, Mauco G, Tallineau C. Cyclooxygenase 1-dependent production of F2-isoprostane and changes in redox status during warm renal ischemia-reperfusion. Free Radic Biol Med. 2004;36:1034–1042. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pratico D, FitzGerald GA. Generation of 8-epiprostaglandin F2α by human monocytes: discriminate production by reactive oxygen species and prostaglandin endoperoxide synthase-2. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:8919–8924. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.15.8919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pratico D, Lawson JA, FitzGerald GA. Cyclooxygenase-dependent formation of the isoprostane, 8-epiprostaglandin F2α. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:9800–9808. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.17.9800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bachi A, Brambilla R, Fanelli R, Bianchi R, Zuccato E, Chiabrando C. Reduction of urinary 8-epi-prostaglandin F2α during cyclo-oxygenase inhibition in rats but not in man. Br J Pharmacol. 1997;121:1770–1774. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schweer H, Watzer B, Seyberth HW, Nusing RM. Improved quantification of 8-epi-prostaglandin F2α and F2-isoprostanes by gas chromatography/triple-stage quadrupole mass spectrometry: partial cyclooxygenase-dependent formation of 8-epi-prostaglandin F2α in humans. J Mass Spectrom. 1997;32:1362–1370. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9888(199712)32:12<1362::AID-JMS606>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Edin ML, Wang Z, Bradbury JA, Graves JP, Lih FB, DeGraff LM, Foley JF, Torphy R, Ronnekleiv OK, Tomer KB, Lee CR, Zeldin DC. Endothelial expression of human cytochrome P450 epoxygenase CYP2C8 increases susceptibility to ischemia-reperfusion injury in isolated mouse heart. FASEB J. 2011;25:3436–3447. doi: 10.1096/fj.11-188300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee CR, Imig JD, Edin ML, Foley J, DeGraff LM, Bradbury JA, Graves JP, Lih FB, Clark J, Myers P, Perrow AL, Lepp AN, Kannon MA, Ronnekleiv OK, Alkayed NJ, Falck JR, Tomer KB, Zeldin DC. Endothelial expression of human cytochrome P450 epoxygenases lowers blood pressure and attenuates hypertension-induced renal injury in mice. FASEB J. 2010;24:3770–3781. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-160119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nugteren DH, Christ-Hazelhof E. Chemical and enzymic conversions of the prostaglandin endoperoxide PGH2. Adv Prostag Thromb Res. 1980;6:129–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chan JA, Nagasawa M, Takeguchi C, Sih CJ. On agents favoring prostaglandin F formation during biosynthesis. Biochemistry. 1975;14:2987–2991. doi: 10.1021/bi00684a030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hamberg M, Samuelsson B. Detection and isolation of an endoperoxide intermediate in prostaglandin biosynthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1973;70:899–903. doi: 10.1073/pnas.70.3.899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Taylor AW, Bruno RS, Frei B, Traber MG. Benefits of prolonged gradient separation for high-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry quantitation of plasma total 15-series F2-isoprostanes. Anal Biochem. 2006;350:41–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2005.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fam SS, Morrow JD. The isoprostanes: unique products of arachidonic acid oxidation-a review. Curr Med Chem. 2003;10:1723–1740. doi: 10.2174/0929867033457115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hempel SL, Monick MM, Hunninghake GW. Lipopolysaccharide induces prostaglandin H synthase-2 protein and mRNA in human alveolar macrophages and blood monocytes. J Clin Invest. 1994;93:391–396. doi: 10.1172/JCI116971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Basu S, Eriksson M. Oxidative injury and survival during endotoxemia. FEBS Letters. 1998;438:159–160. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)01290-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Basu S. Oxidative injury induced cyclooxygenase activation in experimental hepatotoxicity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;254:764–767. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Basu S. Novel cyclooxygenase-catalyzed bioactive prostaglandin F2α from physiology to new principles in inflammation. Med Res Rev. 2007;27:435–468. doi: 10.1002/med.20098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Granström E, Samuelsson B. On the metabolism of prostaglandin F2α in female subjects : II. structures of six metabolites. J Biol Chem. 1971;246:7470–7485. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.