Evolution of the chloroplast from an endosymbiont to an organelle involved the transfer of many genes and regulatory functions to the nucleus, as well as a shift from mainly regulating the initiation of transcription to regulating additional, posttranscriptional steps (reviewed in Barkan, 2011). Sequence-specific RNA binding proteins, such as pentatricopeptide repeat (PPR) proteins, have significant roles in chloroplast gene expression. PRR proteins, named for a repeated domain of 35 amino acids, bind RNA and function in many posttranscriptional regulatory processes, possibly acting by recruiting other proteins or by preventing the RNA from interacting with other factors.

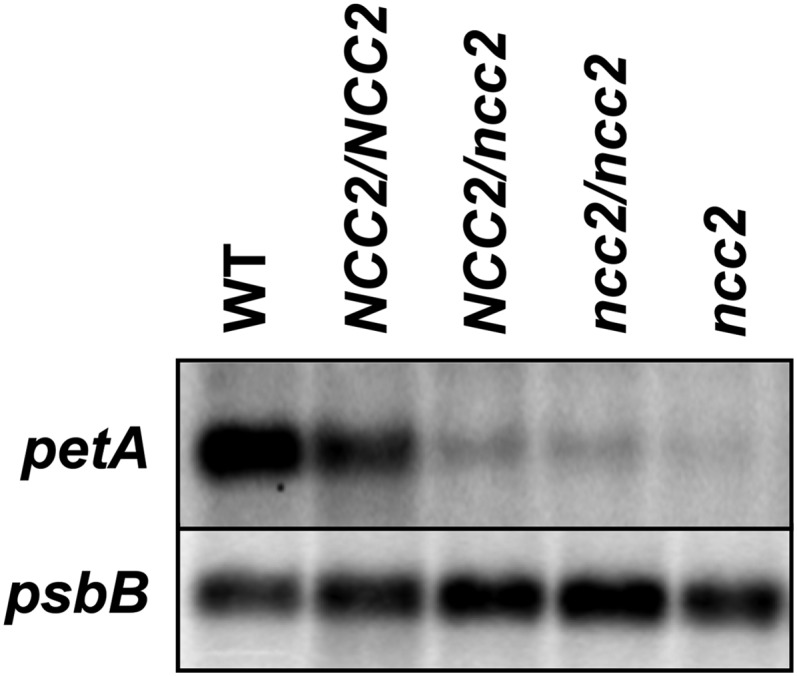

To screen for mutants in nuclear genes that affect chloroplast gene expression in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, Boulouis et al. (2015) expressed psbB, which encodes a core component of photosystem II, under the control of the 5′ untranslated region (UTR) of the chloroplast gene petA, which encodes a subunit of cytochrome b6f. Expression from the 5′petA-psbB construct does not produce enough photosystem protein for the cells to grow photoautotrophically. The authors identified a spontaneous, dominant mutant that allowed photoautotrophic growth, which they named ncc2 (nuclear control of chloroplast gene expression2). In ncc2 mutants, the native petA transcript was degraded (see figure), which affected levels of this cytochrome f subunit. In a phenomenon known as controlled by epistasy of synthesis (Barkan, 2011), the resulting decrease in unassembled cytochrome f subunits triggered increased translation of petA, also increasing translation of the 5′petA-psbB mRNA, thus boosting levels of photosystem II and allowing photoautotrophic growth. A similar mutant, ncc1, produces an altered protein that targets the transcript of the chloroplast atpA gene for degradation.

The ncc2 mutation affects petA transcript abundance. The dominant, nuclear mutation ncc2 results in loss of petA mRNA, but not psbB. (Reprinted from Boulouis et al. [2015], Figure 2E.)

The authors used map-based cloning to show that ncc1 and ncc2 affect OPR (octotricopeptide repeat) proteins. In contrast to the hundreds of PPR proteins in Arabidopsis thaliana and other land plants, the Chlamydomonas genome encodes only 14 PPRs; however, it encodes more than a hundred OPRs, which have a repeated domain of 38 amino acids. Similar to the 35-amino acid PPR domain, the 38-amino acid OPR domain also likely folds into antiparallel α-helices. ncc1 and ncc2 both cause the respective mutant proteins (NCC1M and NCC2M) to acquire new RNA targets. Unlike other known factors that affect the stability of chloroplast mRNAs by targeting the 5′UTR, NCC1M and NCC2M target the coding sequences of atpA and petA, respectively. Intriguingly, NCC2M requires active translation for degradation of petA, but NCC1M does not require active translation of atpA. The authors also identified the target of NCC1M as NAGNGATTA and NCC2M as GTGAGGNTA.

Like PPRs, many OPRs evolve rapidly, and the NCC and NCC-Like genes comprise 38 closely related genes, 32 of which occur in a single cluster on chromosome 15. Examination of the ratio of nonsynonymous-to-synonymous substitutions showed that the NCC and NCC-like genes have experienced diversifying selection, possibly as part of a cycle of duplication and divergence that has expanded the numbers and the functions of these OPRs in RNA metabolism. However, the functions of wild-type NCC1 and NCC2 and the other NCC-like proteins remain to be examined. Understanding the nucleic acid binding specificity of these OPR proteins, identifying their wild-type functions, and revealing the mechanisms by which they affect chloroplast transcripts will help us learn more about the evolutionary dynamics of nuclear regulation of organellar gene expression. Understanding these proteins may also enable biotechnological manipulation of chloroplast RNA metabolism for multiple potential applications, including development of novel cytoplasmic male sterility traits in multicellular plants, alteration of chloroplast metabolites, and improvement of photosynthesis.

References

- Barkan A. (2011). Expression of plastid genes: organelle-specific elaborations on a prokaryotic scaffold. Plant Physiol. 155: 1520–1532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulouis A., Drapier D., Razafimanantsoa H., Wostrikoff K., Tourasse N.J., Pascal K., Girard-Bascou J., Vallon O., Wollman F.-A., Choquet Y. (2015). Spontaneous dominant mutations in Chlamydomonas highlight ongoing evolution by gene diversification. Plant Cell 27: 984–1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]