Abstract

Co-morbid asthma in sickle cell disease (SCD) confers higher rates of vaso-occlusive pain and mortality, yet the physiological link between these two distinct diseases remains puzzling. We utilized a mouse model of SCD to study pulmonary immunology and physiology before and after the induction of allergic airway disease (AAD). SCD mice were sensitized with ovalbumin (OVA) and aluminum hydroxide by the intraperitoneal (IP) route followed by daily, nose-only OVA-aerosol challenge to induce AAD. The lungs of naive SCD mice showed signs of inflammatory and immune processes: (1) histologic and cytochemical evidence of airway inflammation as compared to naïve wildtype mice; (2) bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BAL) contained increased total lymphocytes, %CD8+ T cells, G-CSF, IL-5, IL-7, and CXCL1, and (3) lung tissue and hilar lymph node (HLN) had increased CD4+, CD8+, and regulatory T cells (Tregs). Further, SCD mice at AAD demonstrated significant changes compared to the naïve state: (1) BAL with increased %CD4+ T cells and Tregs, lower %CD8+ T cells, and decreased IFNγ, CXCL10, CCL2, and IL-17, (2) serum with increased OVA-specific IgE, IL-6, and IL-13, and decreased IL-1α and CXCL10, (3) no increase in Tregs in the lung tissue or HLN, and (4) hypo-responsiveness to methacholine challenge. In conclusion, SCD mice have an altered immunologic pulmonary milieu and physiologic responsiveness. These findings suggest that the clinical phenotype of AAD in SCD mice differs from that of wildtype mice and suggests that individuals with SCD may also have a unique, divergent phenotype perhaps amenable to a different therapeutic approach.

Introduction

Pulmonary diseases, such as asthma and acute chest syndrome, are major determinants of mortality in individuals with SCD 1. In fact, asthma is an independent predictor of mortality in patients with SCD2–5. Airway hyper-responsiveness is detectable in up to 83% of adults and children with SCD, significantly more frequently than in healthy controls3,6–9. Exact mechanisms leading to airway hyper-responsiveness in SCD are unknown.

Interestingly and conversely, in a cohort of 99 children with SCD, 30% were found to be hypo-responsive to maximal doses of methacholine raising the question of whether what appears to be asthma in SCD is really related to classic bronchoconstriction10. Investigations of experimental asthma in the SCD mouse model to date reveal histopathologic evidence of an enhanced asthma phenotype, increased total plasma IgE, and elevated bronchoalveolar lavage fluid pro-inflammatory cytokines including IL-13 and IL-511.

Allergic asthma is a chronic allergic disorder characterized by airway smooth muscle hyper-responsiveness, bronchial inflammation with increased mucus secretion, airway remodeling, and increased serum IgE levels12–14. The pathogenesis and immunology of this disease are complex with mast cells, dendritic cells, T- and B-lymphocytes, and eosinophils all playing significant roles15. The increase in eosinophils and CD4+ T lymphocytes in the bronchial mucosa and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid are characteristic features of the inflammatory response in patients with asthma and in animal models of allergic airway disease (AAD)16–19. Increased numbers of CD4+ T cells isolated in bronchial mucosa and peripheral blood in asthma patients appear to correlate with the severity of the disease and have been shown to secrete IL-2 and Th2 cytokines such as IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 which attract and activate eosinophils and regulate the synthesis of IgE from B cells15,17–21.

Individuals living with SCD have increased levels of circulating endothelial cells and pro-inflammatory cytokines at baseline and even higher at times of vaso-occlusion, providing evidence that endothelial inflammation and injury play important roles in mechanisms involved in vascular dysfunction22,23. Holtzclaw et al have shown that low-dose LPS challenge in transgenic SCD mice provokes an exaggerated inflammatory response with elevated levels of TNFα, IL-1β, and soluble VCAM-1 in the serum and BAL fluid24. Our group has previously reported an altered baseline immunophenotype in the serum, gut, and spleen of SCD mice25, raising speculation that disruption in SCD splenic lymphofollicular morphology results in impaired systemic immunity. Furthermore, we have shown sensitization with systemically administered ovalbumin (OVA)/alum leads to increased mortality, antigen-specific serum IgE, and BAL fluid IL-6, and IL-1β26. Additionally, Nandekar et al demonstrated histopathological evidence of enhanced pulmonary inflammation in SCD mice under an experimental asthma protocol27. Altogether, these findings support the contention that both humans and mice with SCD live in states of heightened baseline inflammation which might translate into robust immune responses to antigenic challenge. This, in turn, may predispose them to exaggerated allergic airway responses to inhaled allergens and, at least in part, explain the pulmonary complications observed in SCD.

Co-morbid asthma in SCD is a major contributor to mortality3,4, yet mechanistic insights into its pathogenesis have been sparse. Herein, we utilized a mouse model of SCD to study inflammatory factors involved in the genesis of asthma by employing a well-characterized OVA-induced allergic airway disease (AAD) model. We hypothesized that altered immune responses to allergens occur in SCD mice which give rise to a heightened asthma phenotype. The purpose of our study was to specifically investigate the immune response to AAD in SCD mice which may give mechanistic insights into novel therapies for SCD-related asthma.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Three groups of female mice were used: C57BL/6 (C57 control), transgenic sickle cell mice (SCD mice), and hemizygous sickle cell littermates (hemizygous). All mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA) and were 8–12 weeks of age and weighed 15–25 g at the time of sacrifice. Berkeley sickle cell transgenic mice [Tg(Hu-miniLCRα1GγAγδβS) Hba−/− Hbb−/−] expressing human HBA and HBBS and no longer expressing mouse Hba and Hbb were used as a murine model of SCD28. The stock background of this strain is a mixture of FVB/N, 129, DBA/2, Black Swiss and >50% C57BL/6 genomes. It was backcrossed to C57BL/6 one generation after importation to the Jackson Laboratory. Littermate controls of the Berkeley transgenic SCD mouse (generated on the same mixed background of strains) that express no mouse Hba, but do express one copy of mouse Hbb, human HBA and HBBS giving rise to a hemizygous, sickle cell trait-like genotype were used as a second control arm.

All mice were housed conventionally in plastic cages with corncob bedding. The mouse room was maintained at 22–24°C with a daily light/dark cycle (light from 0600 to 1800h). Chow and water were supplied ad libitum. The protocols for mice used were approved by the Animal Care Committee at the University of Connecticut Health Center and conform to ethical guidelines for animal research.

OVA Exposure Protocol

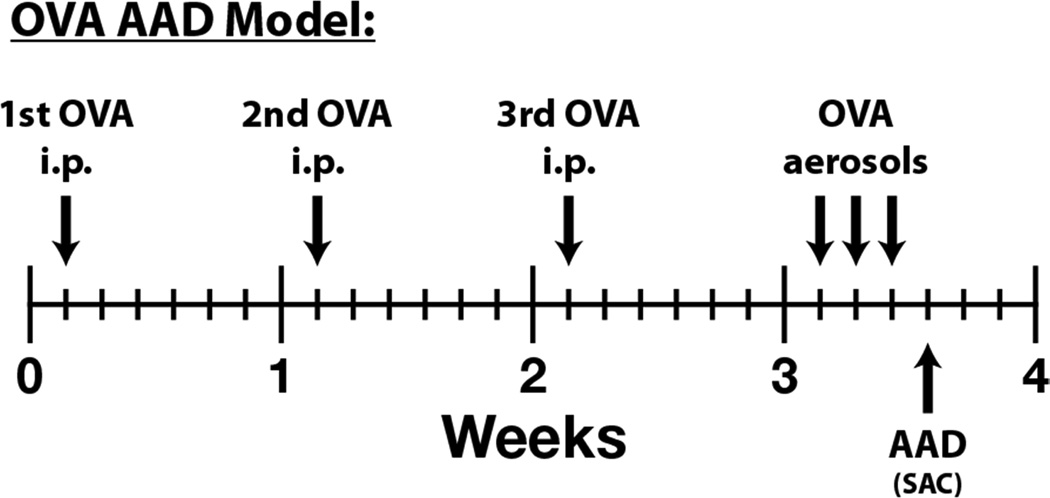

As depicted in Figure 1, mice were immunized with three weekly intraperitoneal (i.p.) injections of a suspension containing 25 µg of OVA (grade V, Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO) and 2 mg of aluminum hydroxide (alum) in 0.5 ml of saline. One week after the last injection, the mice were exposed to 1% aerosolized OVA in physiologic saline, 1 hour/day, for 3 days29. The mice were placed in plastic restraint tubes (Research and Consulting Co., Basel, Switzerland) for nose-only aerosol exposure. The aerosols were generated by a BANG nebulizer (CH Technologies, Westwood, NJ) into a 7.6-L inhalation exposure chamber to which restraint tubes were attached. Chamber airflow was 6 L/minute and aerosol particle size of OVA was monitored by gravimetric analysis with a Mercer cascade impactor (In-Tox Products). The mass median aerodynamic diameter and geometric standard deviations (GSDs) were 1.4 and 1.6 µm, respectively. The estimated daily inhaled OVA dose approximated 30–40 µg/mouse30.

Figure 1. OVA-Induced AAD (asthma) Model.

To investigate the mechanisms and therapeutic targets of allergic asthma, we utilize a well characterized ovalbumin (OVA)-induced allergic airway disease (AAD) model. Following a three week period of OVA sensitization (one i.p. per week), mice are exposed to nose-only OVA-aerosol challenge for 1 hour per day for 3 days. (i.p. = intraperitoneal, SAC = sacrifice)

Harvesting of Samples: Blood, BAL, Lung tissue, and Hilar Lymph Node

Twenty-four hours after the final aerosol exposure, the mice were sacrificed by ketamine/xylazine overdose and samples collected from the various tissues and compartments as previously described30–32. Briefly, whole blood was immediately collected via cardiac puncture into non-heparinized tubes and allowed to clot at room temperature. Serum was collected after centrifugation at 4,000 rpm and frozen for later use at −80°C. A bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) was performed immediately after sacrifice in situ with five 1 mL aliquots of sterile saline. Lung draining (hilar) lymph nodes (HLN) were harvested and mechanically disrupted into a single-cell suspension. In addition, lungs were isolated from un-lavaged mice, minced, and treated with collagenase solution (150 U/mL, Gibco, Grand Island, NY) for 1 hour at 37°C. The minced tissue was mechanically disrupted through a 40-µm nylon filter (BD Falcon, Bedford, MA). Red blood cells were lysed with Tris ammonium chloride. For all tissue samples, total nucleated cell counts were obtained using a hemocytometer with nigrosin dye exclusion as a measure of viability. Aliquots containing 106 cells were resuspended in FACS buffer. Leukocyte differentials were determined in BAL fluid using cytocentrifuged preparations stained with May-Grünwald/Giemsa. The remaining cells were analyzed phenotypically for subpopulations using specific antibodies and fluorescence flow cytometry. BAL protein concentrations were measured in the supernatants by bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay using bovine serum albumin as a standard (Pierce Rockford, IL).

Antibodies

The following monoclonal antibodies were utilized in this study for flow cytometry: CD3-Cy5.5 (145-2C11, BD Biosciences (BD)), CD4-APC-Cy7 (RM4-5, BioLegend), CD8-FITC (53-6.72, BD), CD25-PE (PC61.5, eBioscience), Foxp3-APC (FJR-16s, eBioscience). Corresponding isotype controls were also purchased and utilized.

FACS analysis

Cell pellets containing lymphocytes from tissue preparations were resuspended in PBS solution (containing 0.2% BSA and 0.1% NaN3) at a concentration of 1 × 105 – 1 × 106 white blood cells/ml, and 100 µl of the cells were diluted 1:1 with 100 µl of the appropriate monoclonal antibody and incubated at 4°C for 30 min. Foxp3+ Treg cells were identified by staining lymphocytes with anti-CD3, anti-CD4, and anti-CD25, followed by permeabilization using fixation/permeabilization buffer, per the manufacturer’s instructions. Cells were then stained using an anti-Foxp3 antibody. After staining, cells were washed twice with PBS solution (0.2% BSA and 0.1% NaN3) and relative fluorescence intensities were determined using an LSR-II (Becton-Dickinson, San Diego, CA) and analyzed with FlowJo flow cytometry analysis software (Ashland, OR). Fluorescence minus one (FMO) controls were used to assist with gating.

Cytokine/Chemokine Measurements

Frozen serum samples obtained from mice were thawed and utilized for analysis. Samples were processed using a Milliplex Mouse Cytokine/Chemokine 22-plex kit (Cat #MPXMCYTO70KPMX22; Millipore; Billerica, MA) following the manufacturer’s instructions and utilizing a 1:2 dilution. BAL fluid cytokines were processed and analyzed using the same technique as serum, but sterile PBS was used as a diluent for the standard curve. Samples were analyzed using a Bio-Rad Bioplex-200 system, with recombinant murine cytokines as standards, and Luminex bead array software was used to analyze the data.

OVA-Specific Serum IgE Levels

OVA-specific IgE levels in serum samples were measured by an ELISA using isotype-specific capture monoclonal antibodies33. IgE was captured from serum (diluted 10- to 1,280-fold) using Immulon 2 microtiter plates (Dynatech Laboratories, Chantilly, VA) coated with anti-mouse IgE (R35-72) (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA) at 2 µg/ml in 0.1 mol/L carbonate, pH 9.5. Detection was with an OVA-digoxigenin conjugate followed by horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-digoxigenin, essentially as described34 Development was with the TMB microwell peroxidase substrate system (Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories, Gaithersburg, MD).

Histology

After sacrifice, unmanipulated (not subject to BAL) and non-inflated lungs from separate animals (n = 6–8) were removed, fixed with 10% buffered formalin, and processed in a standard manner. Tissue sections were stained with Hematoxylin and Eosin, Mallory Trichrome (collagen) and Periodic acid-Schiff (mucus)35. Sections from all five lobes were examined in their entirety in a blinded manner for qualitative analysis.

Airway Hyperreactivity

Airway responses to methacholine were assessed by whole-body barometric plethysmography, as previously described36. Mice were studied 24 hours after the third OVA aerosol. Mice were placed in individual chambers (Buxco Electronics, Troy, NY) and exposed for 2 minutes to aerosolized saline or increasing concentrations of methacholine from 3 to 300 mg/ml. Respiratory system variables including tidal volume, respiratory frequency, inspiratory and expiratory times, and changes in box pressure were recorded before and during aerosolization and for 4 minutes after each exposure. The maximal enhanced pause (Penh) value response to methacholine was recorded at each dose.

Statistical Analyses

Statistical comparisons between groups were made with analysis of variance and unpaired t-tests using JMP Software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) and GraphPad Prism 6 (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA). For comparisons between three or more groups, a Tukey post-hoc test was performed. All data were expressed as means +/− standard error of the mean. Methacholine response curves were compared by computing the area under the curves (AUC) and comparing AUCs using ANOVA and a Tukey post-hoc test. Differences were considered significant if p < 0.05.

Results

Lung Histopathology

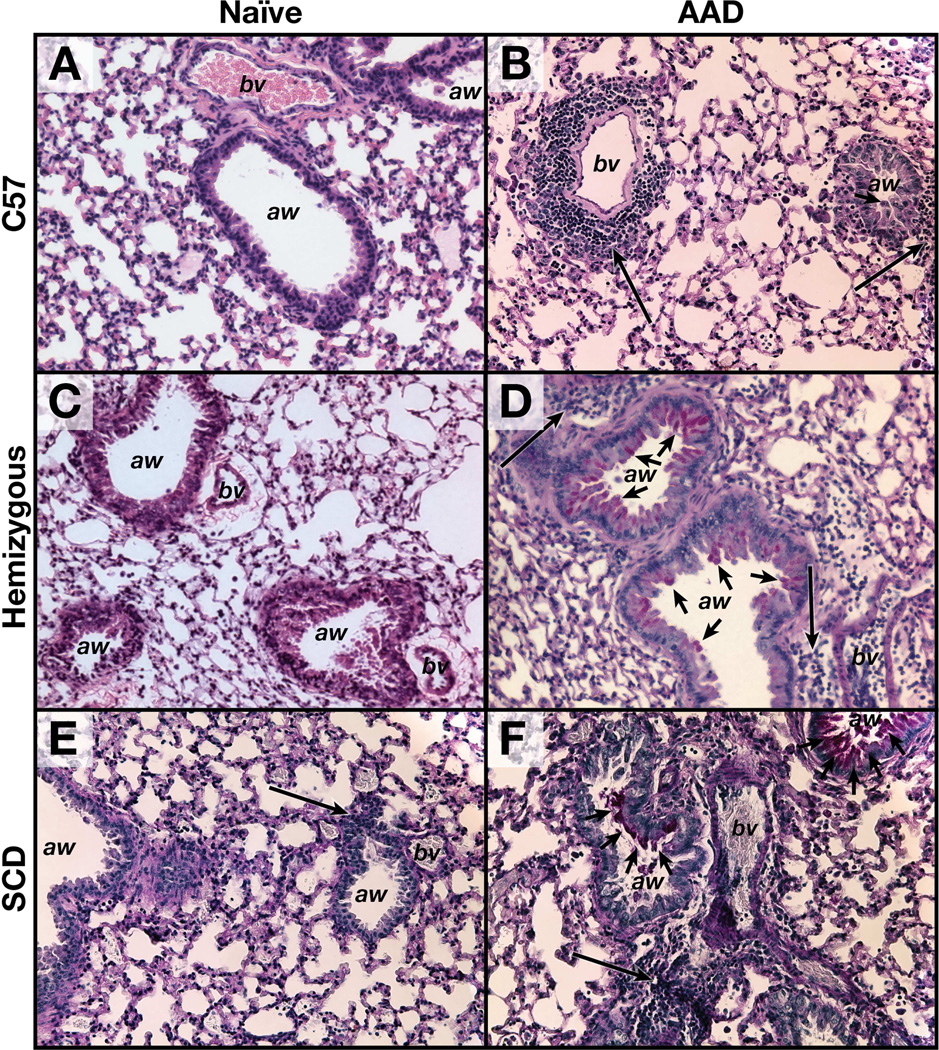

Histopathology specimens demonstrate classical evolution of lung pathology from naïve to OVA-induced AAD in wild-type C57 mice as previously demonstrated29. Naïve C57 mice show lung histopathologic findings devoid of peri-bronchial inflammation and mucus staining (Figure 2A). Upon induction of AAD, the C57 mice show airway luminal narrowing, increased mucus staining (short arrows) and increased peri-bronchial/peri-vascular cellularity (Figure 2B). Interestingly, naïve SCD mice exhibit a baseline increase in perivascular cellular infiltration (Figure 2E). SCD mice show even greater enhancement of airway mucus production and perivascular cellularity at AAD as compared to the naïve state (Figure 2F). Hemizygous mice were histopathologically similar to C57 mice in both the naïve and AAD states (Figures 2C and 2D).

Figure 2. Sickle AAD mice have increased lung inflammation and mucus.

Images are 20x magnification. Short arrows denote PAS+ stain indicative of mucus, whereas long arrows represent the peri-vascular/peri-bronchial inflammation. A= naïve C57, B = AAD C57, C= naïve hemizygous, D = AAD hemizygous, E = naïve SCD, F = AAD SCD. aw=airway. bv=blood vessel.

AAD induces enhanced BAL leukocyte and eosinophil counts in SCD mice as compared to C57 wildtype mice

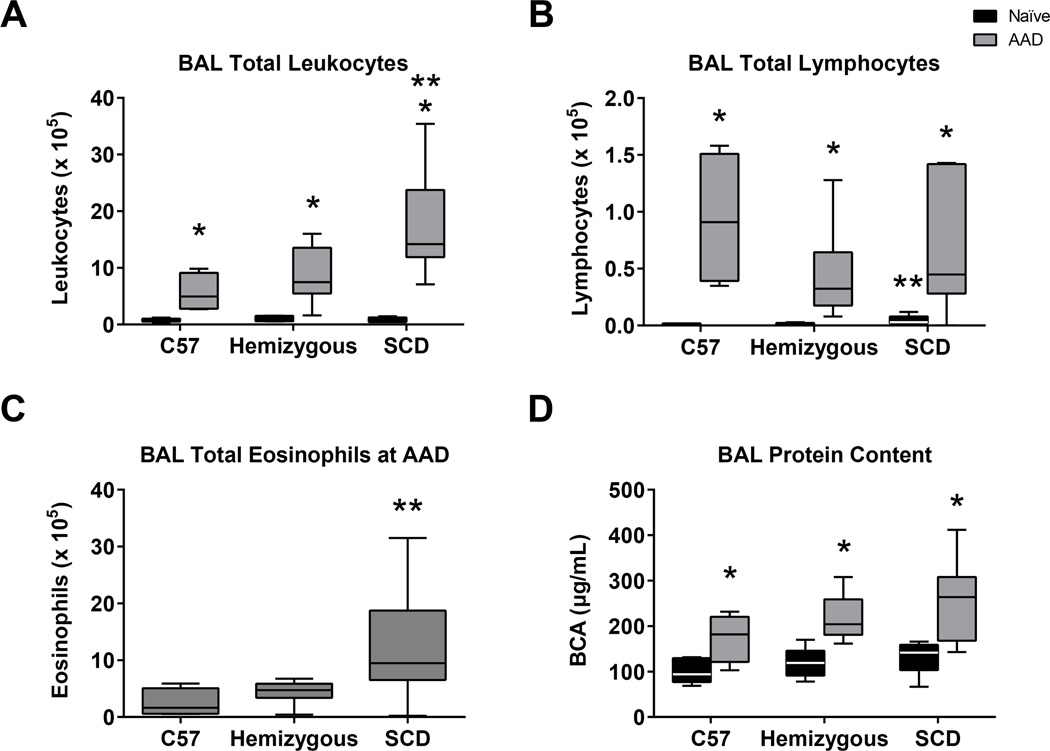

Although the total number of leukocytes in the BAL in the naïve C57, hemizygous and SCD are similar (0.7, 1.0 and 0.8 × 105, respectively, Figure 3A), the SCD mice have a significantly increased total BAL lymphocyte count (0.05 × 105) compared to C57 and hemizygous mice (0.01 and 0.02 × 105, respectively, p=0.0006 Figure 3B). At AAD, all three groups of mice demonstrate significant increases in BAL total leukocyte count compared to the naïve state (Figure 3A, p=0.004). However, SCD mice display a significantly more robust BAL leukocytosis and eosinophilia at AAD (Figures 3A and 3C) suggestive of more profound allergic response to inhaled OVA (both p<0.03). There were no eosinophils observed in the BAL of any of the mouse groups in the naïve state. Leukocyte differentials are reported in Table 1. There is no difference in BAL protein concentration among SCD mice compared to the C57 and hemizygous control mice in the naïve state, nor at AAD (Figure 3D). However, there is a statistically significant increase in BAL protein concentration within each mouse group when comparing the naïve to the AAD state (p<0.01 for each group).

Figure 3. AAD induces shifts in BAL leukocyte counts and differentials in SCD mice but no difference in protein.

Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid was assessed for total leukocyte count (A), differentials (B, C) and protein concentration (D) from naïve C57 (n=6), hemizygous (n=6) and SCD (n=5) mice and compared to BAL from C57 (n=4), hemizygous (n=10) and SCD (n=7) mice after three weekly i.p. OVA-alum sensitizations followed by 3 days of OVA aerosolization. Boxes represent 25-75th percentiles. Whiskers represent minimum and maximum values. Medians are represented by a black or whitehorizontal line within boxes. Significant differences were determined by one-way ANOVA with multiple post-hoc pair-wise comparisons between groups using a student’s t-test. Differences between the naïve and AAD state of an individual mouse group is denoted by an asterisk (*). Differences between SCD mice and both C57 and hemizygous mice is denoted by two asterisks (**).

Table 1.

Comparison of BAL Leukocyte Differentials in Naïve and AAD Mice

| %Lymphocytes | %PMNs | %Macrophages | %Eosinophils | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Naïve | C57 | 2 (0) | 0 (0) | 98 (1) | 0 (0) |

| Hemizygous | 2 (0) | 0 (0) | 98 (1) | 0 (0) | |

| SCD | 5 (1) | 0 (0) | 95 (2) | 0 (0) | |

| AAD | C57 | 16 (1) | 8 (3) | 41(13) | 35 (9) |

| Hemizygous | 6 (1) | 4 (1) | 40 (4) | 51 (5) | |

| SCD | 3 (1) | 3 (3) | 32 (8) | 61 (11) |

All three groups of AAD mice were sensitized and challenged with ovalbumin. Relative to naive unexposed animals, AAD mice demonstrated increases in airway eosinophils and decreases in airway macrophages. There was no significant change in airway polymorphonuclear (PMN) cells at AAD between mouse groups. Data represent mean ± SEM values.

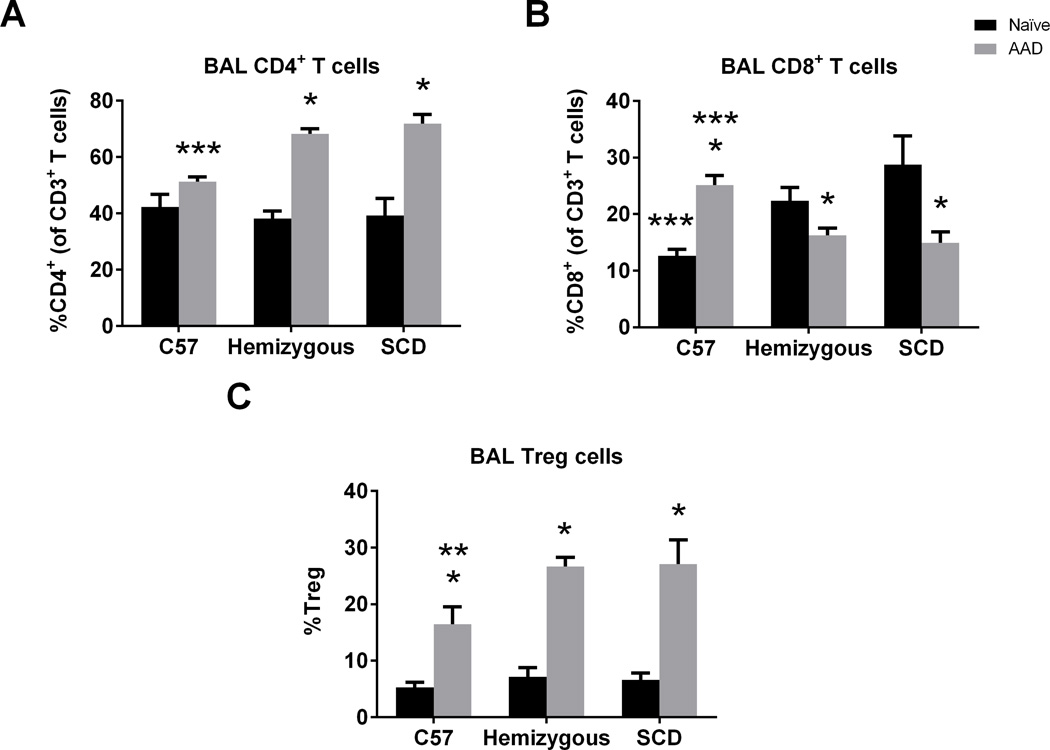

BAL T cell sub-populations are altered at baseline and at AAD in SCD mice

Given the central role of T cells in the genesis of asthma14,18,19, immunophenotyping of BAL T cells was undertaken at the naïve state and after induction of AAD (Figure 4). The BAL of naïve SCD and hemizygous mice had a higher percentage of CD8+ T cells (Figure 4B, p=0.007) as compared to naïve C57 mice but no difference in %CD4+ T cells (Figure 4A) or %Treg cells (Figure 4C). In AAD SCD and AAD hemizygous mice, there were significantly higher %CD4+ T cells in BAL than C57 mice with a concomitant decrease in %CD8+ T cells (Figures 4A and 4B, p<0.004). Although all mouse groups had increases in %Treg cells in the BAL at AAD (p<0.0003) compared to the naïve state, consistent with previous results in C57 mice32, SCD mice displayed a significantly higher percentage of Treg cells at AAD compared to C57s (p=0.04). There was no significant difference at AAD between SCD and hemizygous mice.

Figure 4. BAL T cell sub-populations are altered at baseline and at AAD in SCD mice.

Lymphocyte flow cytometric analysis of BAL cells from C57, hemizygous, and SCD at baseline (n = 6, 6, and 5, respectively) and at AAD (n = 4, 10, and 7, respectively). CD4+ T cells are CD3+CD4+ lymphocytes. CD8+ T cells are CD3+CD8+ lymphocytes. Treg cells are CD3+CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ lymphocytes. Bars represent mean levels +/− SEM. Significant differences were determined by one-way ANOVA with multiple post-hoc, pair-wise comparisons between groups using a students’s t-test. Differences between the naïve and AAD state of an individual mouse group are denoted by an asterisk (*). Differences between C57 controls and SCD mice at AAD are denoted by two asterisks (**). Differences between C57 controls and both hemizygous and SCD mice in the naïve state or at AAD are denoted by three asterisks (***).

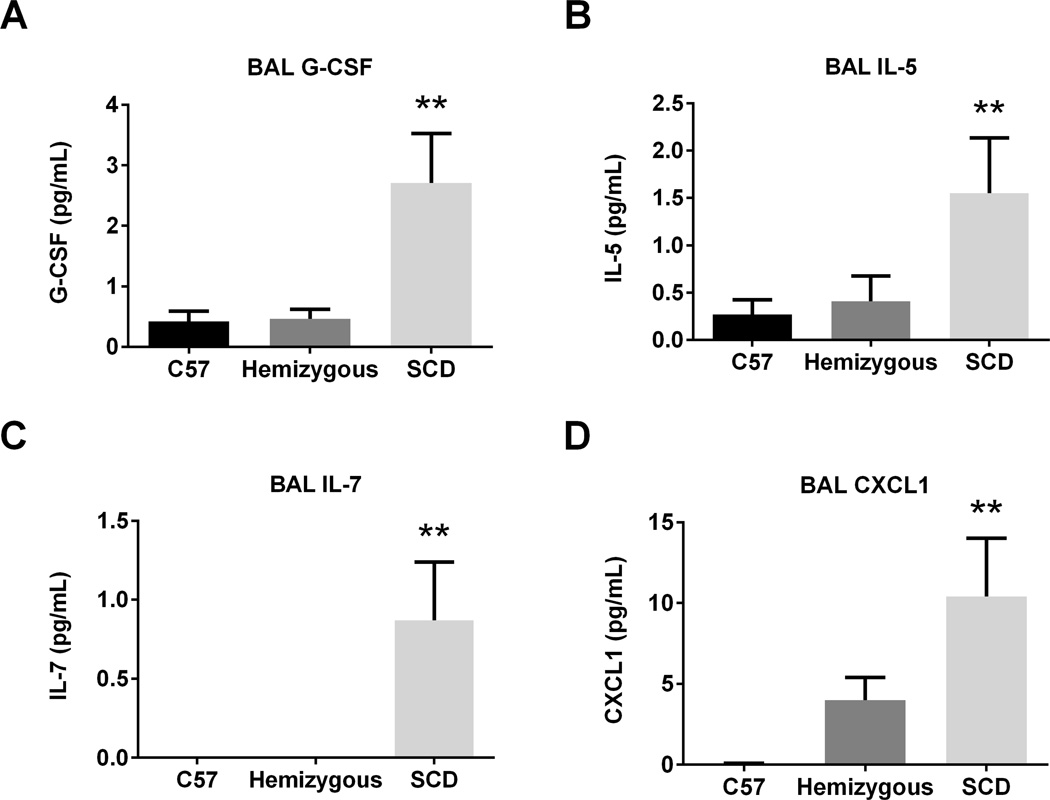

Naive SCD mice have increased BAL G-CSF, IL-5, IL-7, and CXCL1

We measured 17 cytokines and 5 chemokines in the BAL of SCD, hemizygous and C57 mice (Figure 5A–D). G-CSF, IL-5, and IL-7 were significantly higher in concentration in SCD mice compared to both C57 and hemizygous mice in the naïve state (p=0.004, 0.049, and 0.008, respectively for each cytokine). The chemokine CXCL1 was significantly increased in the BAL of naïve SCD mice as compared to C57 and hemizygous mice (p=0.01). There was no difference in levels of the cytokines GM-CSF, IFNγ, IL-1b, IL-2, IL-4, IL-9, IL-19, IL-12, IL-13, IL-15, IL-17, or TNFα (data not shown). Additionally, there was no difference in levels of the chemokines CCL2, CCL3, CCL5, or CXCL10 (data not shown).

Figure 5. Naïve SCD mice have increased BAL G-CSF, IL-5, IL-7, and CXCL1.

BAL was assessed from naïve C57 (n=6), hemizygous (n=6), and SCD (n=5) mice for cytokine and chemokine concentration via Luminex bead assay. Bars represent mean levels +/− SEM. Significant differences were determined by one-way ANOVA with multiple post-hoc, pair-wise comparisons between groups using a student’s t-test. Differences between SCD mice and both C57 and hemizygous mice are denoted by two asterisks (**).

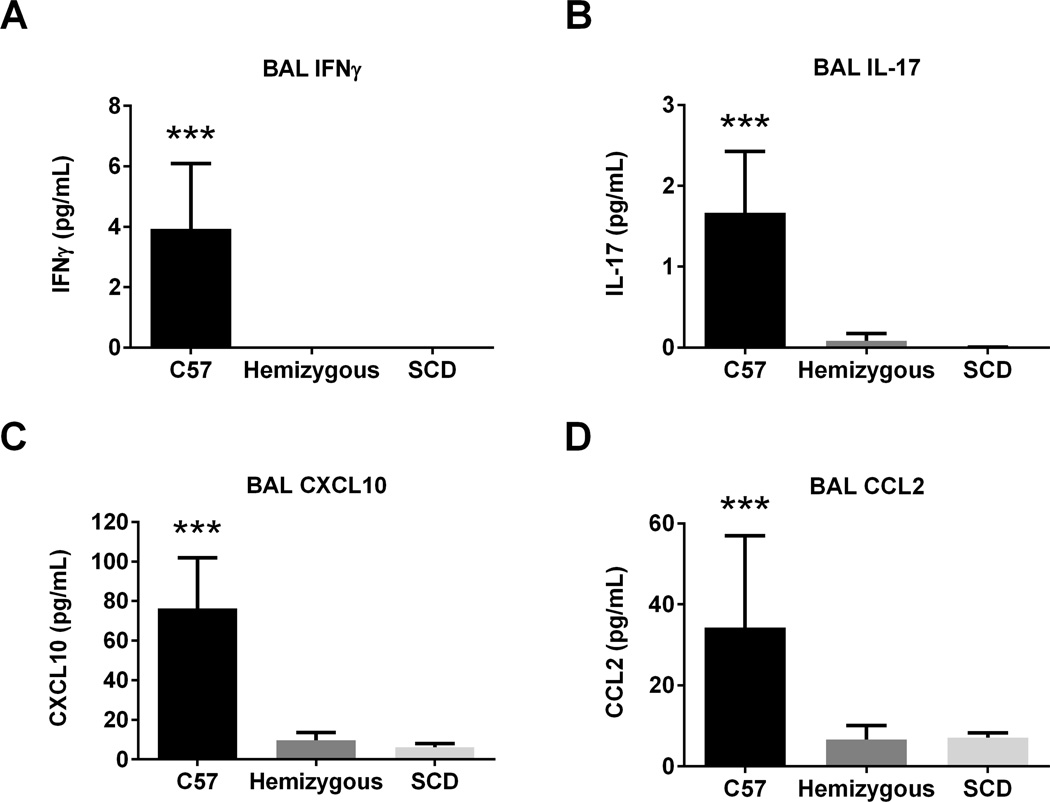

SCD mice have lower BAL IFNγ, IL-17, CXCL10, and CCL2 at AAD

At AAD, none of the 22 measured cytokines/chemokines were increased in the BAL of SCD mice as compared to control mice (Data not shown). However, as demonstrated in Figure 6, two cytokines and two chemokines were significantly decreased in the BAL of SCD mice compared to C57 and hemizygous mice: IFNγ, IL-17, CXCL10, and CCL2 (p=0.003, 0.001, 0.0002, and 0.04, respectively).

Figure 6. AAD SCD mice have lower BAL concentrations of IFNγ, IL-17, CXCL10, and CCL2.

BAL was assessed after induction of AAD from C57 (n=4), hemizygous (n=10), and SCD (n=7) mice for cytokine and chemokine concentration via Luminex bead assay. Bars represent mean levels +/− SEM. Significant differences were determined by one-way ANOVA with multiple post-hoc, pair-wise comparisons between groups using a student’s t-test. Differences between C57 mice and both hemizygous and SCD mice are denoted by three asterisks (***).

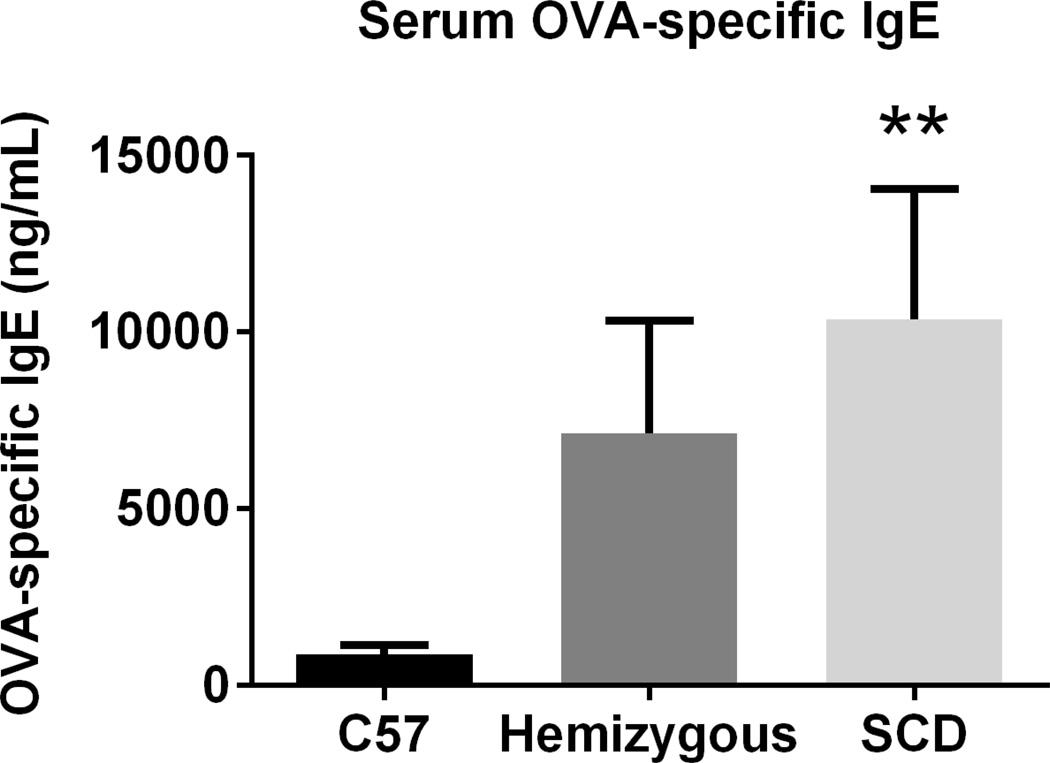

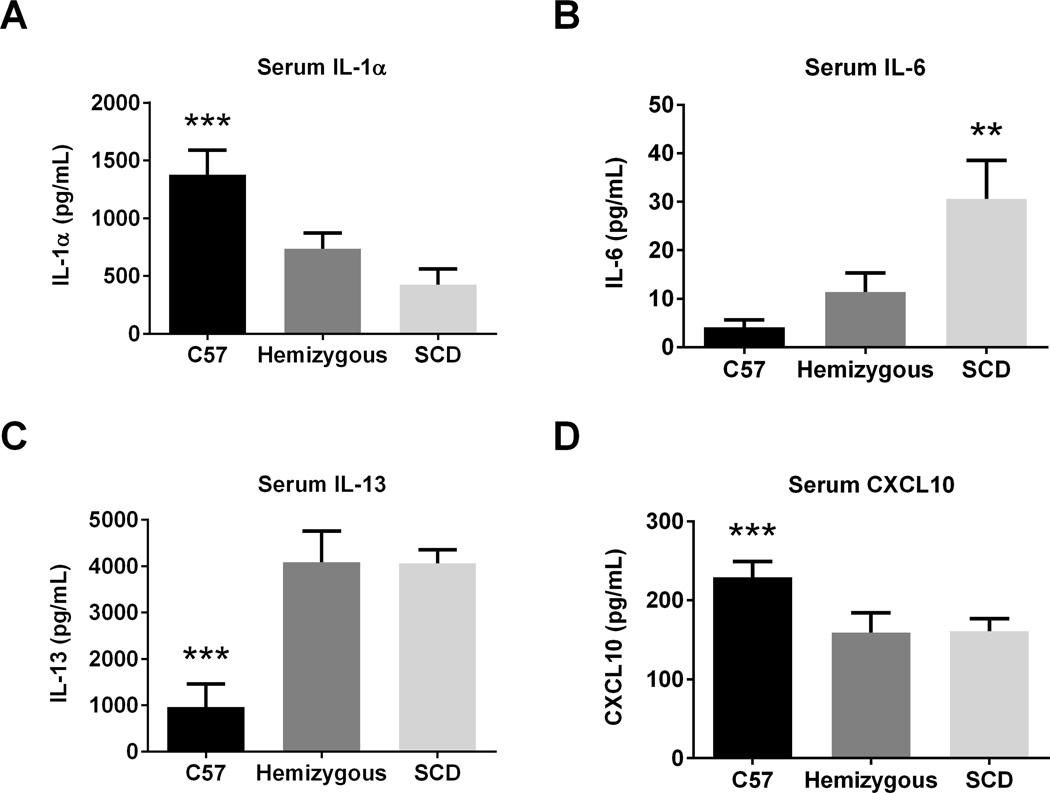

At AAD, SCD mice demonstrate enhanced serum OVA-specific IgE, IL-6, and IL-13, but decreased IL-1α and CXCL10

Serum OVA-specific IgE levels in the SCD mice were significantly greater than in C57 mice at AAD (p=0.03, Figure 7). Although serum OVA-specific IgE levels were higher in hemizygous mice compared to C57s, this was not statistically significant (p=0.14). As shown in Figure 8, SCD mice at AAD have significantly increased serum IL-6 and IL-13 as well as decreased serum IL-1α and CXCL10 levels as compared to C57 controls (all p<0.04). Except for significantly decreased serum levels of IL-6 at AAD, the hemizygous mice were similar to SCD mice.

Figure 7. Serum OVA-specific IgE is 10-fold higher in SCD mice at AAD.

Serum OVA-specific IgE was measured using a capture ELISA. C57 (n=9), hemizygous (n=9) and SCD (n=10) mice were analyzed after induction of AAD. Bars represent mean levels +/− SEM. Significant differences were determined by one-way ANOVA with multiple post-hoc, pair-wise comparisons between groups using a student’s t-test. Differences between SCD and C57 mice are denoted by two asterisks (**).

Figure 8. AAD induces an altered serum cytokine profile in SCD mice.

Serum was assessed for AAD C57 (n=8), hemizygous (n=8), and SCD (n=8) mice for cytokine and chemokine concentration via Luminex bead assay. Bars represent mean levels +/− SEM. Significant differences were determined by one-way ANOVA with multiple post-hoc, pair-wise comparisons between groups using a student’s t-test. Differences between SCD mice and both C57 and hemizygous mice are denoted by two asterisks (**). Differences between C57 mice and both hemizygous and SCD mice are denoted by three asterisks (***).

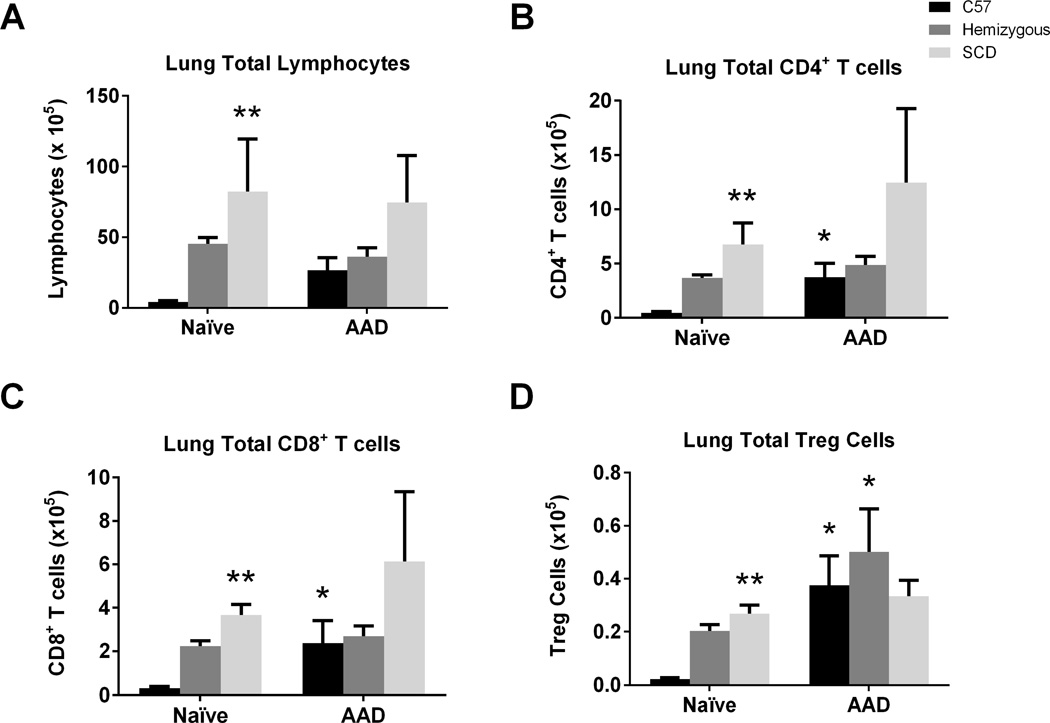

SCD mice have increased T cell sub-populations in lung tissue in the naïve state, but not at AAD

Immunophenotyping of lung tissues demonstrated that in the naïve state the SCD mouse lung has increased total lymphocytes, CD4+ T cells and CD8+ T cells compared to C57 control mice (Figure 9A–C; all p<0.02). Further sub-characterization of the CD4+ T cell subset identifies an increase in total Treg cells as well (Figure 9D; p<0.0001).

Figure 9. Lung T cell sub-populations are increased in the naïve state but not at AAD in SCD mice.

Lymphocyte flow cytometric analysis of lung mononuclear cells from C57, hemizygous, and SCD mice at baseline (n = 6, 6, and 4, respectively) and at AAD (n = 4, 10, and 7, respectively) was performed. CD4+ T cells are CD3+CD4+ lymphocytes. CD8+ T cells are CD3+CD8+ lymphocytes. Treg cells are CD3+CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ lymphocytes. Bars represent mean levels +/− SEM. Significant differences were determined by one-way ANOVA with multiple post-hoc, pair-wise comparisons between groups using a student’s t-test. Differences between the naïve and AAD state of an individual mouse group is denoted by an asterisk (*). Differences between SCD mice and C57 control mice at the naïve stage is denoted by two asterisks (**).

Interestingly, at AAD, there were no observed differences in total lung lymphocyte counts between SCD mice and both C57 and hemizygous mice (Figure 9A). Although C57 mice demonstrated a robust increase in total CD4+, CD8+, and Treg cells (all p<0.02), there was no increase in the T cell subsets in SCD mice after AAD induction (Figures 9B–D).

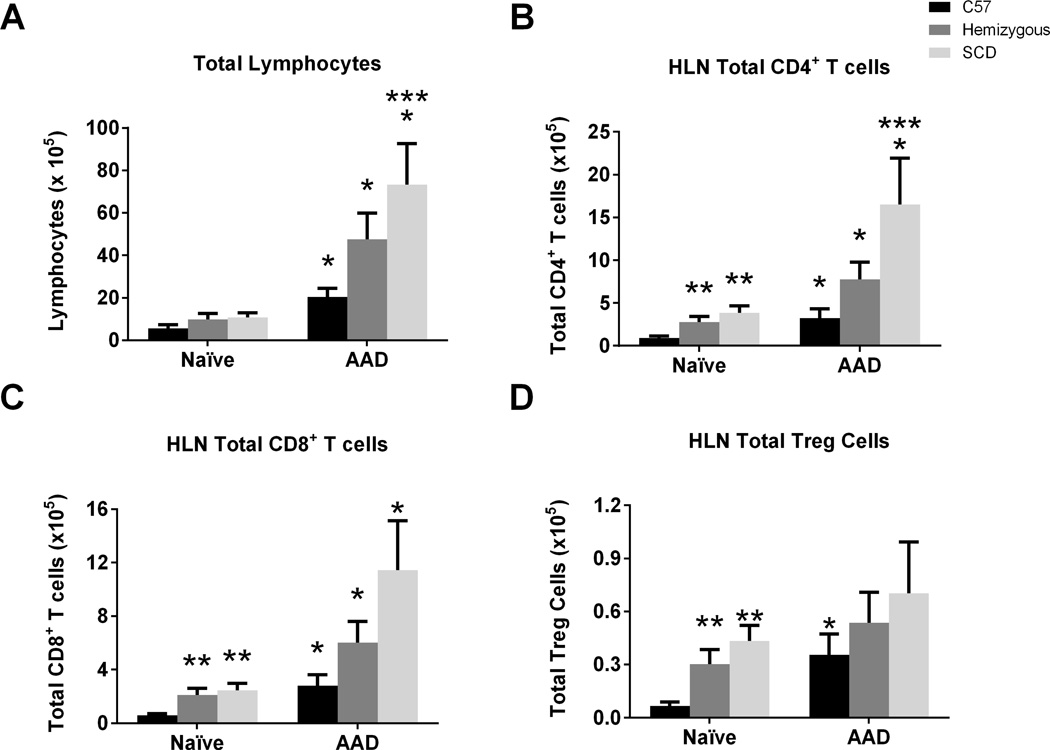

SCD mice have altered T cell sub-populations in the naïve state as well as at AAD

Hilar lymph node (HLN) immunophenotyping of T cells was also performed to assess for potential changes in lymphocyte trafficking from the lung to its draining lymph node. In contrast to the lung tissue, the total lymphocyte count in the naïve HLN was no different between mouse groups. However, at the induction of AAD, there was a greater increase in the HLN lymphocyte count in SCD mice as compared to C57 controls (Figure 10A; p=0.04). T cell immunophenotyping of naïve HLN lymphocytes (Figures 10B and 10C) demonstrated an increase in total CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in the SCD and hemizygous mice compared to C57 mice (both p=0.01). Although all three mouse groups demonstrate increases in total CD4+ and CD8+ T cells at induction of AAD (all p<0.04), SCD mice had significantly higher increases in total CD4+ T cells than C57 mice (Figures 10B; p=0.04). Naïve SCD and hemizygous mice had significantly greater numbers of Treg cells in their HLN compared to C57 mice (Figure 10D; p=0.007). However, while C57 mice demonstrated increased Tregs in the HLN at induction of AAD (p=0.01), SCD and hemizygous mice did not (Figure 10D).

Figure 10. HLN lymphocyte sub-populations are altered in the naïve state and at AAD in SCD mice.

Lymphocyte flow cytometric analysis of hilar lymph node (HLN) mononuclear cells from C57, hemizygous, and SCD mice at baseline (n = 6, 6, and 4, respectively) and at AAD (n = 9, 9, and 10, respectively) was performed. CD4+ T cells are CD3+CD4+ lymphocytes. CD8+ T cells are CD3+CD8+ lymphocytes. Treg cells are CD3+CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ lymphocytes. Bars represent mean levels +/− SEM. Significant differences were determined by one-way ANOVA with multiple post-hoc, pair-wise comparisons between groups using a student’s t-test. Differences between the naïve and AAD state of an individual mouse group is denoted by an asterisk (*). Differences between SCD and hemizygous mice compared to C57 mice at the naïve stage is denoted by two asterisks (**). Differences between C57 mice and SCD mice at AAD are denoted by three asterisks (***).

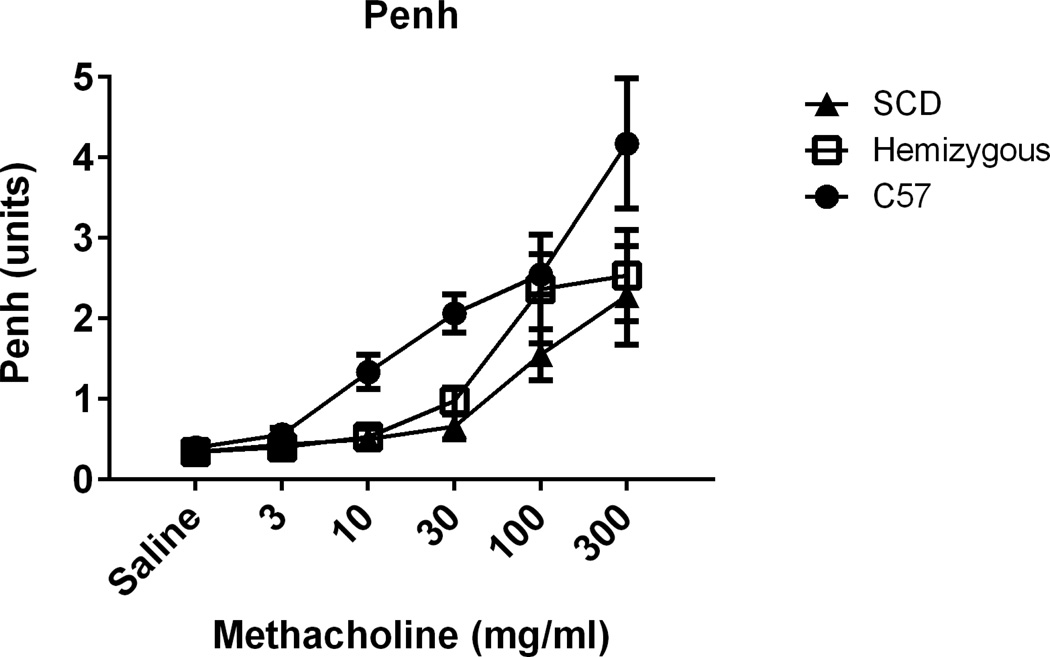

Airway Responsiveness

Airway responsiveness to methacholine challenge was assessed by whole-body barometric plethysmography. As we have observed previously35, C57 mice show airway hyper-responsiveness at AAD, physiologically confirming allergic airway disease. Interestingly, the SCD mice had significantly decreased airway hyper-responsiveness (AHR) as compared to C57 mice at AAD (Figure 11; p < 0.01 by one-way ANOVA). This is in contrast to the observed enhanced cellular inflammatory response on corresponding histopathology and cytochemical analysis of lung lavage. Hemizygous mice demonstrated an intermediate state between SCD and C57 mice (Figure 11).

Figure 11. SCD and hemizygous mice are hyporesponsive to methacholine challenge at AAD.

Airway hyperesponsiveness was assessed at AAD following 3 OVA i.p. sensitizations and 3 days of OVA aerosol challenge. Sensitivity to methacholine challenge was compared between SCD (n=7, closed triangles), hemizygous (n=7, open boxes), and C57 control (n=6, closed circles) mice. Increasing concentrations of methacholine are denoted on the x-axis. Area under the curve (AUC) was computed for each mouse and groups compared using one-way ANOVA and Tukey post-hoc test. Data represent mean ± SEM levels of Penh responses. The overall effect of genotype on methacholine response is significant (p < 0.01). p < 0.01 for C57 versus SCD. p = 0.06 for C57 versus Hemizygous.

Discussion

Asthma is a major contributor to morbidity and mortality in SCD, yet relatively little is known of the pathophysiologic basis of the asthma phenotype in SCD or the interactions between these two disease states. Here, we report that transgenic SCD mice exhibit baseline pulmonary inflammation and a distinct cytokine, chemokine, and cellular milieu at AAD as compared to C57 control mice. Naïve SCD mice are characterized by increased levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines in the BAL, elevated levels of lung CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, and evidence of perivascular cellular infiltration in the lungs. At AAD, SCD mice have increased BAL eosinophils, 10-fold greater serum OVA-specific IgE levels and an altered cytokine profile as compared to C57 controls but do not differ in total cell counts in the lung. Intriguingly, SCD mice are hyporesponsive to methacholine challenge at AAD.

Histopathology and immunophenotyping suggests that naïve SCD mice exist in a pro-inflammatory immune state, in agreement with previous reports from our laboratory25,26 and that of other groups in both mouse models37,38 and in humans with SCD39. The immune system in SCD may be primed to respond aggressively to inhaled allergen by virtue of this pro-inflammatory state, providing one explanation for the high morbidity and mortality seen in SCD patients with asthma. Evidence for such priming can be seen in our previous report of OVA-Alum vaccination in SCD mice and in work by Nandekar et al, where high mortality was present exclusively in SCD mice undergoing experimentally-induced asthma27. This priming is likely the driving force behind the 10-fold higher levels of serum OVA-specific IgE and several-fold higher BAL leukocyte and eosinophil counts we observed in SCD mice at AAD. Higher naive SCD BAL levels of G-CSF, IL-5, and IL-7 may collectively be major drivers of eosinophil recruitment and lung remodeling, particularly IL-5, an important Th2-skewing cytokine14. Targeted therapy to reduce the Th2 response, such as the anti-IL-5 monoclonal antibody mepolizumab, should be investigated pre-clinically as a means to reduce the robust allergic response in SCD.

Additionally, the pro-inflammatory immune state we describe may arise from an erythrocytic source: free heme. SCD is characterized by a state of chronic hemolysis, resulting in release of free heme into the circulating plasma. Free heme is a potent pro-inflammatory mediator through its induction of cytokine release, leukocyte activation, and TLR4-mediated activation of the innate immune system40,41. Indeed, heme-induced TLR4 activation of endothelial cell adhesion molecules has been found to play a role in vaso-occlusion in mouse models of SCD42, and its presence could bias the immune system toward a pro-inflammatory state and influence subsequent development of allergic airway disease.

The cellular disturbances we note in SCD mice may provide additional mechanistic explanations for the severity of asthma in human SCD. The perivascular clusters of inflammatory cells in the lungs of naive mice may at least partially account for the increase in IgE and related cytokines like IL-13 at AAD. Immunophenotyping revealed many of the cells in the lungs and BAL of naive mice to be CD4+ and CD8+ T, and these may be pre-positioned to receive stimulus from antigen-presenting cells that process OVA and initiate a robust inflammatory response. The presence of increased CD8+ T cell numbers is particularly noteworthy, as multiple reports have suggested that CD8+ T cells can modulate allergic responses by influencing CD4+ T cells43–45. However, these same reports also pointed to CD8+ T cell production of IFNγ as a key mediator of disease suppression, and IFNγ is many-fold reduced in the BAL of SCD mice at AAD when compared to C57 controls. This suggests that SCD may be associated with a defect in IFNγ production by CD8+ T cells, and it is perhaps for this reason that the increase in percentage of CD4+ T cells in the BAL from naïve to AAD is greater in SCD than in C57 controls.

Interestingly, such a defect may not be limited to CD8+ T cells. The presence of increased Treg numbers in the lung and HLN in naive SCD mice as well as the sharp increase in BAL Tregs in AAD SCD mice would seem to predict heightened capacity for regulation and disease suppression. However, there is some evidence that Tregs in SCD display an altered phenotype and may have reduced immunosuppressive capacity, although the latter remains debated46,47. Of particular note, alloimmunization associated with frequent blood transfusion, a mainstay of treatment of SCD, may produce dysfunction in both Tregs46 and regulatory B cells (Bregs)48. We and others have shown that Tregs32,49,50 and Bregs30,31,51 play important roles in the regulation of allergy and asthma. Taken together, these findings suggest that the presence of regulatory immune cells may not be sufficient to alleviate the burden of asthma in SCD and suggests dysfunctional immune regulation and suppression by these cells. Future studies of the regulatory function of these cell populations are warranted to determine the specific contribution of each to asthma pathophysiology in SCD.

Interestingly, while lung lymphocytes were increased in SCD as compared to C57 controls in the naïve state, total numbers did not increase at AAD, in sharp contrast to C57s, where the increase is over 6-fold. The lack of increase of lung Tregs at AAD in SCD when compared to C57 controls is particularly noteworthy given the role of these cells in modulating allergic diseases32. This disruption in lymphocyte kinetics may have multiple etiologies. It is increasingly recognized that SCD is associated with profound disturbances in endothelial cells, including increased numbers of circulating, activated endothelial cells22; disruption of nitric oxide and regulation of vascular caliber52,53; and poor response of endothelial cells to shear stress54,55. Endothelial cells are important mediators of transmigration of lymphocytes from the circulation into tissues, and disturbance of these cells could be expected to impair migration. It is also possible that the dysfunction involves endothelial cells but is not directly related to their lack of function. Multiple reports have noted that erythrocytes in SCD are more adherent56–59, particularly to activated endothelium. In the presence of a multitude of adherent erythrocytes, competition for adhesion sites on endothelial cells may be too great for the relatively smaller number of lymphocytes to successfully adhere and pass through the vascular wall. It will be important for future investigations to examine lymphocyte migration, or lack thereof, in SCD.

A further possibility concerns the sphingolipid sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P), an important mediator of lymphocyte trafficking. Under normal circumstances, activated lymphocytes leave the lymph node by following a gradient of S1P into the blood, where it is higher than in the node60. In SCD, blood levels of S1P are elevated and have been shown to be associated with sickling and general disease progression61. It may be that elevated S1P is another impediment to lymphocytes migrating from the blood into tissues, as they are subjected to a constant tug back into the blood by the unusually high S1P concentration. Further evaluation of the specific role of S1P in co-morbid SCD and asthma is warranted.

It is also possible that the initial sites of inflammation in the lung parenchyma, visible even in the naïve state, provide a source of cells that can proliferate and migrate into the BAL fluid as disease develops despite poor migration from the blood. The lack of increased protein leak in SCD relative to C57 controls is consistent with a local generation of these additional cells, as increased vascular permeability, which could also produce elevated BAL cellularity, would be expected to raise the concentration of protein in the BAL.

Despite increased baseline pulmonary inflammation and a robust serum IgE response to OVA administration, SCD mice proved resistant to methacholine-induced airway constriction after induction of AAD. A recent report of a cohort of children with SCD noted that nearly a third were hypo-responsive to methacholine challenge10, suggesting a similar disease process might be occurring in the SCD mouse and human SCD patients. Furthermore, others have also described evidence of airway obstruction despite a lack of airway hyper-reactivity (AHR) in SCD62, and there is some evidence that bronchodilators provide diminished symptomatic relief in SCD63. Taken together, this could indicate that the obstruction present may not arise from airway smooth muscle constriction but rather from some other obstructive force not responsive to methacholine challenge. Such findings would necessitate a reexamination of current clinical practices for the treatment of asthma in SCD, perhaps supplementing or replacing conventional asthma treatment with alternative therapies in this unique disease state. One possibility, recently raised by studying children with SCD63, is that vascular congestion and corresponding vascular enlargement could be producing airway obstruction in the absence of AHR, consistent with reported poor efficacy of bronchodilators in the SCD population.

The disturbed cytokine/chemokine milieu provides for a possible mechanistic explanation for the airway hypo-reactivity. Both IFNγ and CXCL10 have been shown to be important for the development of airway hyper-reactivity, and we found these to be deficient in SCD mice at AAD. Both are also deficient in hemizygous mice, potentially explaining the attenuated response to methacholine challenge also seen in these animals.

Intriguingly, our findings contrast with those of Pritchard et al11, who reported significantly increased AHR in SCD mice at AAD and in the naïve state. One possible explanation for this difference concerns the unique aspects of our respective SCD models. The SCD model examined in our study is a transgenic mouse expressing human globins, including sickle beta globin, from birth. Contrastingly, Pritchard et al performed a bone marrow transplant into wild type mice from a transgenic SCD mouse11. Those mice were allowed to recover for 8 weeks, and demonstrated many of the hallmark pathologies of SCD, but they did not develop from birth in the presence of sickling erythrocytes and consequently their organ function and pathology may vary from an animal exposed to sickling cells for the entire postnatal period.

Co-morbid asthma in SCD is a predictor of future morbidity, mortality, and consequently quality of life. Much effort has been directed at the clinical interaction of asthma and SCD, but the underlying pathophysiologic process remains unclear. Herein, we describe the application of a well-established OVA-induced model of murine AAD to SCD. Naïve SCD mice exist in a pro-inflammatory Th2 state prior to induction of AAD with elevated CD4+ T cells in the HLN and lung tissue. It may be this predisposition to Th2-mediated inflammation evidenced by elevated naïve BAL levels of the Th2 cytokine IL-5 that produces the enhanced allergic response seen at AAD. SCD mice have 10-fold greater levels of OVA-specific IgE in the blood than C57 controls as well as increased overall cellularity and eosinophil number in BAL at AAD. Surprisingly, but consistent with previous clinical reports, SCD and hemizygous mice are hypo-responsive to methacholine challenge at AAD. SCD mice have low levels of IFNγ at AAD as compared to C57 controls, and this cytokine may be a crucial player in the lack of AHR. Lack of AHR in the mouse model of allergic airway disease suggests standard clinical therapy with bronchodilators may be ineffective in this population and warrants further investigation. Observed similarities between SCD and hemizygous mice suggest evaluation of sickle cell trait as a potential risk factor for asthma susceptibility should be investigated clinically.

In summary, further study of models of asthma in SCD such as that utilized herein may provide important insights into disease pathophysiology and drive development of new therapeutic modalities for these intertwined conditions.

Brief Commentary.

Background

Co-morbid asthma is an independent predictor of morbidity and mortality in sickle cell disease (SCD). Although both diseases are hallmarked by altered inflammatory states, the pathophysiological link between these two biologically distinct processes remains elusive. Herein, we utilize a mouse model of SCD to study inflammatory and lung mechanics changes in experimentally-induced asthma.

Translational Significance

Our work has the potential to drive development of new therapeutic modalities for humans living with both SCD and asthma. Lack of airway hyper-reactivity in the mouse model suggests standard clinical therapy with bronchodilators may be ineffective in this population and warrants further investigation. Further, since airway hyper-reactivity is a major component in the diagnosis of asthma, it may be under-diagnosed in this population.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Connecticut Institute for Clinical and Translational Science (CICATS) Clinical and Translational Scholars K12 Award, Lea’s Foundation for Leukemia Research, Inc., and NIAID R01 AI043573.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

All authors have read the journal's policy on disclosure of potential conflicts of interest and find no potential conflicts of interest. All authors have read the journal’s authorship agreement. The manuscript has been reviewed and approved by all named authors. No editorial support was provided for preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Miller AC, Gladwin MT. Pulmonary complications of sickle cell disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012 Jun 1;185(11):1154–1165. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201111-2082CI. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Platt OS, Brambilla DJ, Rosse WF, et al. Mortality in sickle cell disease Life expectancy and risk factors for early death. N Engl J Med. 1994 Jun 9;330(23):1639–1644. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199406093302303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Knight-Madden JM, Forrester TS, Lewis NA, Greenough A. Asthma in children with sickle cell disease and its association with acute chest syndrome. Thorax. 2005 Mar;60(3):206–210. doi: 10.1136/thx.2004.029165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boyd JH, Macklin EA, Strunk RC, DeBaun MR. Asthma is associated with increased mortality in individuals with sickle cell anemia. Haematologica. 2007 Aug;92(8):1115–1118. doi: 10.3324/haematol.11213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Intzes S, Kalpatthi RV, Short R, Imran H. Pulmonary function abnormalities and asthma are prevalent in children with sickle cell disease and are associated with acute chest syndrome. Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2013 Nov;30(8):726–732. doi: 10.3109/08880018.2012.756961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leong MA, Dampier C, Varlotta L, Allen JL. Airway hyperreactivity in children with sickle cell disease. J Pediatr. 1997 Aug;131(2):278–283. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(97)70166-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ozbek OY, Malbora B, Sen N, et al. Airway hyperreactivity detected by methacholine challenge in children with sickle cell disease. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2007 Dec;42(12):1187–1192. doi: 10.1002/ppul.20716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sen N, Kozanoglu I, Karatasli M, et al. Pulmonary function and airway hyperresponsiveness in adults with sickle cell disease. Lung. 2009 Jun;187(3):195–200. doi: 10.1007/s00408-009-9141-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vendramini EC, Vianna EO, De Lucena Angulo I, et al. Lung function and airway hyperresponsiveness in adult patients with sickle cell disease. Am J Med Sci. 2006 Aug;332(2):68–72. doi: 10.1097/00000441-200608000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Field JJ, Stocks J, Kirkham FJ, et al. Airway hyperresponsiveness in children with sickle cell anemia. Chest. 2011 Mar;139(3):563–568. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-1243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pritchard KA, Jr, Feroah TR, Nandedkar SD, et al. Effects of experimental asthma on inflammation and lung mechanics in sickle cell mice. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2012 Mar;46(3):389–396. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2011-0097OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Robinson DS, Hamid Q, Ying S, et al. Predominant TH2-like bronchoalveolar T-lymphocyte population in atopic asthma. N Engl J Med. 1992 Jan 30;326(5):298–304. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199201303260504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ricci M, Rossi O, Bertoni M, Matucci A. The importance of Th2-like cells in the pathogenesis of airway allergic inflammation. Clin Exp Allergy J Br Soc Allergy Clin Immunol. 1993 May;23(5):360–369. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.1993.tb00340.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Till S, Durham S, Dickason R, et al. IL-13 production by allergen-stimulated T cells is increased in allergic disease and associated with IL-5 but not IFN-gamma expression. Immunology. 1997 May;91(1):53–57. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1997.00218.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barrios RJ, Kheradmand F, Batts L, Corry DB. Asthma: pathology and pathophysiology. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2006 Apr;130(4):447–451. doi: 10.5858/2006-130-447-APAP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Azzawi M, Bradley B, Jeffery PK, et al. Identification of activated T lymphocytes and eosinophils in bronchial biopsies in stable atopic asthma. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1990 Dec;142(6 Pt 1):1407–1413. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/142.6_Pt_1.1407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McFadden ER, Gilbert IA. Asthma. N Engl J Med. 1992 Dec 31;327(27):1928–1937. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199212313272708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Walker C, Kaegi MK, Braun P, Blaser K. Activated T cells and eosinophilia in bronchoalveolar lavages from subjects with asthma correlated with disease severity. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1991 Dec;88(6):935–942. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(91)90251-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garlisi CG, Falcone A, Hey JA, et al. Airway eosinophils, T cells, Th2-type cytokine mRNA, and hyperreactivity in response to aerosol challenge of allergic mice with previously established pulmonary inflammation. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1997 Nov;17(5):642–651. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.17.5.2866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Walker C, Bode E, Boer L, et al. Allergic and nonallergic asthmatics have distinct patterns of T-cell activation and cytokine production in peripheral blood and bronchoalveolar lavage. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1992 Jul;146(1):109–115. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/146.1.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lewkowich IP, Herman NS, Schleifer KW, et al. CD4+CD25+ T cells protect against experimentally induced asthma and alter pulmonary dendritic cell phenotype and function. J Exp Med. 2005 Dec 5;202(11):1549–1561. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Solovey A, Lin Y, Browne P, et al. Circulating activated endothelial cells in sickle cell anemia. N Engl J Med. 1997 Nov 27;337(22):1584–1590. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199711273372203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pathare A, Al Kindi S, Alnaqdy AA, et al. Cytokine profile of sickle cell disease in Oman. Am J Hematol. 2004 Dec;77(4):323–328. doi: 10.1002/ajh.20196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holtzclaw JD, Jack D, Aguayo SM, et al. Enhanced pulmonary and systemic response to endotoxin in transgenic sickle mice. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004 Mar 15;169(6):687–695. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200302-224OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Szczepanek SM, McNamara JT, Secor ER, et al. Splenic Morphological Changes Are Accompanied by Altered Baseline Immunity in a Mouse Model of Sickle-Cell Disease. Am J Pathol [Internet] 2012 Sep 19; doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.07.034. [cited 2012 Sep 28]; Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23000264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Szczepanek SM, Secor ER, Jr, Bracken SJ, et al. Transgenic sickle cell disease mice have high mortality and dysregulated immune responses after vaccination. Pediatr Res. 2013 Aug;74(2):141–147. doi: 10.1038/pr.2013.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nandedkar SD, Feroah TR, Hutchins W, et al. Histopathology of experimentally induced asthma in a murine model of sickle cell disease. Blood. 2008 Sep 15;112(6):2529–2538. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-01-132506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pászty C, Brion CM, Manci E, et al. Transgenic knockout mice with exclusively human sickle hemoglobin and sickle cell disease. Science. 1997 Oct 31;278(5339):876–878. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5339.876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yiamouyiannis CA, Schramm CM, Puddington L, et al. Shifts in lung lymphocyte profiles correlate with the sequential development of acute allergic and chronic tolerant stages in a murine asthma model. Am J Pathol. 1999 Jun;154(6):1911–1921. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65449-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Natarajan P, Singh A, McNamara JT, et al. Regulatory B cells from hilar lymph nodes of tolerant mice in a murine model of allergic airway disease are CD5(+), express TGF-β, and co-localize with CD4(+)Foxp3(+) T cells. Mucosal Immunol. 2012 Jun 20; doi: 10.1038/mi.2012.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Singh A, Carson WF, Secor ER, et al. Regulatory Role of B Cells in a Murine Model of Allergic Airway Disease. J Immunol. 2008 Jun 1;180(11):7318–7326. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.11.7318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carson WF, 4th, Guernsey LA, Singh A, et al. Accumulation of regulatory T cells in local draining lymph nodes of the lung correlates with spontaneous resolution of chronic asthma in a murine model. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2008;145(3):231–243. doi: 10.1159/000109292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Matson AP, Zhu L, Lingenheld EG, et al. Maternal transmission of resistance to development of allergic airway disease. J Immunol Baltim Md 1950. 2007 Jul 15;179(2):1282–1291. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.2.1282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Seymour BW, Gershwin LJ, Coffman RL. Aerosol-induced immunoglobulin (Ig)-E unresponsiveness to ovalbumin does not require CD8+ or T cell receptor (TCR)-gamma/delta+ T cells or interferon (IFN)-gamma in a murine model of allergen sensitization. J Exp Med. 1998 Mar 2;187(5):721–731. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.5.721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schramm CM, Puddington L, Wu C, et al. Chronic inhaled ovalbumin exposure induces antigen-dependent but not antigen-specific inhalational tolerance in a murine model of allergic airway disease. Am J Pathol. 2004 Jan;164(1):295–304. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63119-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wu CA, Puddington L, Whiteley HE, et al. Murine cytomegalovirus infection alters Th1/Th2 cytokine expression, decreases airway eosinophilia, and enhances mucus production in allergic airway disease. J Immunol Baltim Md 1950. 2001 Sep 1;167(5):2798–2807. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.5.2798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kaul DK, Hebbel RP. Hypoxia/reoxygenation causes inflammatory response in transgenic sickle mice but not in normal mice. J Clin Invest. 2000 Aug;106(3):411–420. doi: 10.1172/JCI9225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wood KC, Hebbel RP, Granger DN. Endothelial cell P-selectin mediates a proinflammatory and prothrombogenic phenotype in cerebral venules of sickle cell transgenic mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004 May;286(5):H1608–H1614. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01056.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lanaro C, Franco-Penteado CF, Albuqueque DM, et al. Altered levels of cytokines and inflammatory mediators in plasma and leukocytes of sickle cell anemia patients and effects of hydroxyurea therapy. J Leukoc Biol. 2009 Feb;85(2):235–242. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0708445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Figueiredo RT, Fernandez PL, Mourao-Sa DS, et al. Characterization of heme as activator of Toll-like receptor 4. J Biol Chem. 2007 Jul 13;282(28):20221–20229. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610737200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dutra FF, Bozza MT. Heme on innate immunity and inflammation. Front Pharmacol. 2014;5:115. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2014.00115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Belcher JD, Chen C, Nguyen J, et al. Heme triggers TLR4 signaling leading to endothelial cell activation and vaso-occlusion in murine sickle cell disease. Blood. 2014 Jan 16;123(3):377–390. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-04-495887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Marsland BJ, Harris NL, Camberis M, et al. Bystander suppression of allergic airway inflammation by lung resident memory CD8+ T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004 Apr 20;101(16):6116–6121. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401582101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Swain SD, Meissner NN, Harmsen AG. CD8 T cells modulate CD4 T-cell and eosinophil-mediated pulmonary pathology in pneumocystis pneumonia in B-cell-deficient mice. Am J Pathol. 2006 Feb;168(2):466–475. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.050724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Isogai S, Athiviraham A, Fraser RS, et al. Interferon-gamma-dependent inhibition of late allergic airway responses and eosinophilia by CD8+ gammadelta T cells. Immunology. 2007 Oct;122(2):230–238. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2007.02632.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bao W, Zhong H, Li X, et al. Immune regulation in chronically transfused allo-antibody responder and nonresponder patients with sickle cell disease and β-thalassemia major. Am J Hematol. 2011 Dec;86(12):1001–1006. doi: 10.1002/ajh.22167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vingert B, Tamagne M, Desmarets M, et al. Partial dysfunction of Treg activation in sickle cell disease. Am J Hematol. 2014 Mar;89(3):261–266. doi: 10.1002/ajh.23629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bao W, Zhong H, Manwani D, et al. Regulatory B-cell compartment in transfused alloimmunized and non-alloimmunized patients with sickle cell disease. Am J Hematol. 2013 Sep;88(9):736–740. doi: 10.1002/ajh.23488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Romagnani S. Immunologic influences on allergy and the TH1/TH2 balance. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004 Mar;113(3):395–400. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2003.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Larché M. Regulatory T cells in allergy and asthma. Chest. 2007 Sep;132(3):1007–1014. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-2434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tsitoura DC, Yeung VP, DeKruyff RH, Umetsu DT. Critical role of B cells in the development of T cell tolerance to aeroallergens. Int Immunol. 2002 Jun;14(6):659–667. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxf032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Aslan M, Ryan TM, Adler B, et al. Oxygen radical inhibition of nitric oxide-dependent vascular function in sickle cell disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001 Dec 18;98(26):15215–15220. doi: 10.1073/pnas.221292098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kato GJ, McGowan V, Machado RF, et al. Lactate dehydrogenase as a biomarker of hemolysis-associated nitric oxide resistance, priapism, leg ulceration, pulmonary hypertension, and death in patients with sickle cell disease. Blood. 2006 Mar 15;107(6):2279–2285. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-06-2373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kaul DK, Fabry ME, Nagel RL. Microvascular sites and characteristics of sickle cell adhesion to vascular endothelium in shear flow conditions: pathophysiological implications. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989 May;86(9):3356–3360. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.9.3356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Belhassen L, Pelle G, Sediame S, et al. Endothelial dysfunction in patients with sickle cell disease is related to selective impairment of shear stress-mediated vasodilation. Blood. 2001 Mar 15;97(6):1584–1589. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.6.1584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hebbel RP, Schwartz RS, Mohandas N. The adhesive sickle erythrocyte: cause and consequence of abnormal interactions with endothelium, monocytes/macrophages and model membranes. Clin Haematol. 1985 Feb;14(1):141–161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Parise LV, Telen MJ. Erythrocyte adhesion in sickle cell disease. Curr Hematol Rep. 2003 Mar;2(2):102–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Blum A, Yeganeh S, Peleg A, et al. Endothelial function in patients with sickle cell anemia during and after sickle cell crises. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2005 Apr;19(2):83–86. doi: 10.1007/s11239-005-1377-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gutsaeva DR, Montero-Huerta P, Parkerson JB, et al. Molecular mechanisms underlying synergistic adhesion of sickle red blood cells by hypoxia and low nitric oxide bioavailability. Blood. 2014 Mar 20;123(12):1917–1926. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-06-510180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mandala S, Hajdu R, Bergstrom J, et al. Alteration of lymphocyte trafficking by sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor agonists. Science. 2002 Apr 12;296(5566):346–349. doi: 10.1126/science.1070238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhang Y, Berka V, Song A, et al. Elevated sphingosine-1-phosphate promotes sickling and sickle cell disease progression. J Clin Invest. 2014 Jun 2;124(6):2750–2761. doi: 10.1172/JCI74604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chaudry RA, Rosenthal M, Bush A, Crowley S. Reduced forced expiratory flow but not increased exhaled nitric oxide or airway responsiveness to methacholine characterises paediatric sickle cell airway disease. Thorax. 2014 Jun;69(6):580–585. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2013-204464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wedderburn CJ, Rees D, Height S, et al. Airways obstruction and pulmonary capillary blood volume in children with sickle cell disease. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2014 Jul;49(7):716–722. doi: 10.1002/ppul.22845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]