Abstract

Children with poor emotion knowledge (EK) skills are at risk for externalizing problems; less is known about early internalizing behavior. We examined multiple facets of EK and social-emotional experiences relevant for internalizing difficulties, including loneliness, victimization, and peer rejection, in Head Start preschoolers (N = 134; M = 60 months). Results based on multiple informants suggest that facets of EK are differentially related to negative social-emotional experiences and internalizing behavior and that sex plays a moderating role. Behavioral EK was associated with self-reported loneliness, victimization/rejection, and parent-reported internalizing symptoms. Emotion recognition and expressive emotion knowledge were related to self-reported loneliness, and emotion situation knowledge was related to parent-reported internalizing symptoms and negative peer nominations. Sex moderated many of these associations, suggesting that EK may operate differently for girls versus boys in the preschool social context. Results are discussed with regard to the role of EK for social development and intervention implications.

Knowledge of emotions in the self and others develops rapidly during early childhood. A child’s ability to recognize, label, and understand emotions in others is critical for effective social interaction and maintaining social relationships (Denham et al., 2002; 2003). Processing emotion-related information is an important corollary of successful social adjustment during early childhood (typically ages 3–5 years; Halberstadt, Denham, & Dunsmore, 2001) particularly in preschool classroom settings (Arsenio, Cooperman, & Lover, 2000; Miller, Fine, Gouley, Seifer, & Dickstein., 2004). Emotion knowledge (EK) skills are consistently found to be positively related to social competence and negatively related to internalizing and externalizing behavior problems across childhood and adolescence (see Trentacosta & Fine, 2010, for a review). Most studies of preschool-age children (ages 3–6 years), however, focus on EK skills primarily in relation to disruptive and aggressive behaviors (Denham et al., 2002; Martin, Boekamp, McConville, & Wheeler, 2010; Shields et al., 2001) rather than internalizing problems. Furthermore, most studies tend to examine only one aspect of EK, yet different facets of EK may relate differentially to child functioning (Bassett, Denham, Mincic, & Graling, 2012). In the current study, we assessed how different facets of EK were associated with early social-emotional experiences relevant for internalizing difficulties – specifically loneliness, victimization, and peer rejection – and internalizing symptoms in a sample of 4.5–5.6-year-old (M = 60 months) low-income children, as reported by peers, teachers, parents, and the children themselves.

Emotion Knowledge and Social Functioning

EK is a multifaceted construct that includes skills such as labeling emotions; recognizing emotion expressions in others; and correctly attributing emotion states to a particular situation. Such skills are critical for effective regulation of one’s own emotion states (Barrett et al., 2001) as well as engaging in positive social interactions (Denham et al., 2003). EK skills develop in increasing complexity over time, with more basic recognition skills emerging earlier (around age 3 years) than more complex knowledge about ambiguous situations, mixed emotions, or distinctions between felt and displayed emotion, which emerge between 4–7 years (Bassett et al., 2012; Pons, Harris, & DeRosnay, 2004). Such differences in EK represent conceptually different abilities that can serve different functions (Bassett et al., 2012). Recognizing emotions from a picture and generating emotion words are central EK skills. The ability to recognize subtle emotion cues in the moment, however, may be particularly critical in the classroom setting where emotion-laden interactions occur at a rapid pace. Understanding not only how situations can cause peers’ emotional responses (e.g., losing a toy may cause sadness), but also how to “read” emotion behaviors in a peer’s face or body (e.g., crossed arms and frowning eyebrows indicate anger) as they unfold in real time may each be required for effectively navigating the preschool classroom context.

Early EK skills may be uniquely important for understanding early social-emotional experiences that are associated with later internalizing problems, for example, feelings of loneliness, rejection, victimization, and exclusion by peers (Snyder et al., 2003; Sterba, Prinstein, & Cox, 2007). EK has been identified as a predictor of such experiences among older children. In low-income kindergarten and first-graders, poor emotion recognition skills were associated with greater peer victimization (Miller et al., 2005). Poor EK skills in first grade were associated with social withdrawal and rejection (Schultz, Izard, Ackerman, & Youngstrom, 2001), and predicted fifth-grade internalizing behaviors (Fine, Izard, Mostow, Trentacosta, & Ackerman, 2003). Poor EK skills were also associated with internalizing behaviors among 10- and 11-year-olds (Rieffe & Rooij, 2012; Southam-Gerow & Kendall, 2000; Zeman, Shipman, & Suveg, 2002). Yet, associations between EK skills and internalizing difficulties are understudied in children younger than age 5 (Trentacosta & Fine, 2010). This is a notable omission because essential EK skills are typically solidified during early childhood (primarily ages 3–5 years).

In preschool settings, children with poor EK skills may be reluctant to enter peer play situations if they cannot read emotion cues that provide information about the nature of the interaction. Children’s actions based on misreading emotion cues may result in peer rejection or exclusion and negative emotion, which may in turn lead them to withdraw further from social engagement. Of the few studies to examine this in preschoolers, one found that better overall EK, but worse anger perception, was associated with greater peer victimization (Mage = 55 months; Garner & Lemerise, 2007). A recent study of EK, false-belief understanding, and social adjustment in French-speaking preschoolers (Mage = 52 months) found that a lack of EK – specifically, knowledge of contextually-appropriate behavioral emotion responses – was associated with more parent-reported internalizing behavior (e.g., anxiety, isolation), whereas false belief understanding was not (Denault & Ricard, 2013). Thus, EK skills may be uniquely relevant for internalizing behaviors even during the preschool years.

EK is often a focus of preschool intervention programs for young children (ages 3–6 years; e.g., Izard, Trentacosta, King, & Mostow, 2004; Kusché & Greenberg, 1994; Webster-Stratton, 2000), with the idea that if children are better equipped to understand others’ emotion states, they will use that information to engage effectively in social interactions. However, different facets of EK have been associated with different social outcomes (Denham, McKinley, Couchoud, & Holt, 1990; Miller et al., 2005) and it is not known which specific aspects of EK may be most important to focus on to achieve optimal social outcomes. For example, most programs teach children to recognize emotions and to label their own and others’ feelings (Izard, 2001). Although such skills are undeniably important, it is not known how basic naming and labeling skills translate to children’s daily experiences in school. Examining how different facets of EK such as receptive and expressive knowledge of emotion words (i.e., basic EK recognition and expression skills); emotion situation knowledge (i.e., knowledge of which situations typically cause certain emotion states); and behavioral emotion knowledge (i.e., being able to tell which facial, vocal, or behavioral actions reflect different emotion states) relate to children’s social experiences in school, particularly those relevant for internalizing difficulties, should provide additional insight into the role of EK and child experiences.

Limitations of Previous Emotion Knowledge Research

A limitation of previous EK research with preschoolers is that relatively few studies have utilized multiple informants when examining child social experiences and behaviors that may predict later internalizing problems. Instead, most studies of EK rely on teacher reports (Trentacosta & Fine, 2010). Teacher reports are valuable in informing us about child behavior in the classroom, but may be less helpful regarding children’s internal experiences. Teachers are also reliably better at identifying externalizing rather than internalizing problems, which can be under-reported (Lutz, Fantuzzo, & McDermott, 2002). Children’s feelings of loneliness and perceived victimization or rejection by peers may be important indicators of internalizing problems (Reijntjes, Kamphuis, Prinzie, & Telch, 2010), and cannot easily be observed. Young children, however, can reliably report such experience (Burgess, Ladd, Kochenderfer, Lambert, & Birch, 1999; Cassidy & Asher, 1992). Considering children’s self-reported experiences of loneliness, victimization, and peer rejection, as well as reports from teachers, peers and parents has the potential to paint a richer picture of children’s internalizing experiences.

Furthermore, it is important to consider whether EK operates the same way for boys and girls. Sex differences in internalizing behavior can emerge even during early childhood, with higher rates of internalizing problems and different trajectories for toddler girls versus boys (Carter et al., 2010) and across ages 2–11 years (Sterba et al., 2007). Sex differences have also been found for preschool peer victimization such that girls showed more relational aggression than boys (Crick & Bigbee, 1998), although findings are not consistent (Rose & Rudolph, 2006). Sex differences have also been reported in the development of EK, with boys typically demonstrating EK skills later than girls (Brody, 1985; Brown & Dunn, 1996; Cervantes & Callanan, 1998; Izard et al., 2001). With regard to emotion socialization, mothers sanctioned anger displays in boys to a greater degree than girls (Chaplin et al., 2010). Some researchers have suggested there may be sex differences in the meaning of EK for social functioning (Bassett et al., 2012; Cunningham, Kliewer, & Garner, 2009; Dunsmore, Noguchi, Garner, Casey, & Bhullar, 2008). In a small sample of high-income preschoolers (n = 42), Dunsmore et al. (2008) showed that having better EK skills was more beneficial for girls’ social relationships than for boys’. In older children, Cunningham et al. (2009) found that boys, but not girls, benefited from caregivers’ emotion coaching if they had better EK skills, whereas another study showed that third-grade girls’ EK, but not boys’, was related to decreased aggression (Fine, Trentacosta, Izard, Mostow, & Campbell, 2004). Still other studies have not found sex differences (Bassett et al., 2012; Garner & Lemerise, 2007; Zeman, Shipman, & Suveg, 2002). Given the mixed results from previous work, we examined sex as a potential moderator of associations between EK and the social-emotional experiences that may be relevant for internalizing problems, and between EK and internalizing symptoms.

Finally, it is important to note that not all studies of EK consider the role of children’s verbal skills (e.g., Denham et al., 2003), despite the fact that language abilities are consistently associated with EK (Garner & Waajid, 2008; Morgan, Izard, & King, 2010). Child language skills are also known to relate to peer social outcomes (McCabe & Meller, 2004), so it is important to consider whether EK is related to peer social outcomes independent of language skills.

Goal of Current Study and Hypotheses

To address an important methodological gap in our current understanding of EK and early school experience, we included multiple measures of both constructs in the current study. We took this approach in an effort to increase understanding of the relationship between EK and early school experience, and also to identify different patterns of association between EK skills and self- and other-reported internalizing outcomes. We also assessed child language skills in order to examine the potential unique contributions of EK. We conducted this study with children attending Head Start, acknowledging the generally increased risk for difficulties in school associated with growing up in poverty, particularly in the social-emotional domain (Bierman et al., 2008).

Consistent with previous research, our first hypothesis was that greater EK across facets would be related to fewer negative social outcomes. Building on previous studies that examined different facets of EK (Garner & Waajid, 2008; Miller et al., 2005), our second hypothesis was that facets of EK would be differentially related to social outcomes, specifically that more contextually-driven facets of EK (emotion situation knowledge, behavioral emotion knowledge) would better predict social functioning than the more basic EK facets (emotion recognition and expressive knowledge). Our third, exploratory hypothesis was to determine whether these associations differed by child sex by examining EK predictor and sex interactions across each outcome.

Method

Participants

Participants were 134 children attending Head Start in the Northeast U.S. (42% boys; Mage = 60 months, SD = 3.4, Range: 4.47 – 5.63 years). Reflecting the demographics of the region, the sample was 77% Caucasian, 8% African American, and 15% biracial/other, and 16% Latino ethnicity. Family income was $25,740/year, with an average of 2.5 children and 2 adults in the home (M income-to-needs ratio=1.19). Children were participating in a larger study of emotion processing and social competence (removed for review), which entailed additional child assessments after the emotion interviews (described below), but there was no intervention component to the larger study. All procedures were approved by the university hospital IRB. There were 37 classrooms represented, with a maximum of 7 study children in any given classroom (mean of 3.4 children per classroom). Each classroom had approximately 18 children (range: 14–20), one lead teacher, and one teacher’s assistant. Participants were recruited during summertime placement screenings and classroom open houses at Head Start, as well as at the school at pickup and drop-offs. Families were offered $50.00 payment for their participation.

Procedure and Measures

Children were individually interviewed in a quiet room at Head Start to assess their emotion knowledge and social experiences in school by research assistants who were familiar to them from previous data collection efforts. Interviews typically took about 15 minutes to complete. On other days, children participated in assessments involving developmental testing and other tasks (viewing videos) and research assistants observed children in their classrooms. Children’s teachers completed questionnaires to assess child functioning. We focus here on individual child assessment and teacher-report data (collected on average 5 weeks apart).

Language Skills

We assessed child language skills, as these can be associated with EK (Garner & Waajid, 2008). Child language was assessed using the Language subscale of the Developmental Indicators for the Assessment of Learning tool (DIAL-3), which has often been used with low-income populations (Mardell-Czudnowski & Goldenberg, 1998). Children were asked to identify letters and vocabulary words, and to describe how they would respond to different situations. This measure yielded standardized language scores.

Emotion Knowledge

We drew from three EK assessment protocols that have each been used with young, low-income children. Assessments included the Affect Knowledge Test (AKT) (Denham, 1986), the Emotion Matching Test (EMT) (Izard, Haskins, Schultz, Trentacosta, & King, 2003; Morgan et al., 2010), and a portion of the Knowledge Assessment Interview (KAI) (Kusché, Greenberg, & Beikle, 1988). The AKT uses drawn faces, verbal stories, and puppets that act out emotion behavior as stimuli to assess expressive and receptive EK and emotion situation knowledge. The EMT uses photographs of children as stimuli to assess expressive and receptive EK and emotion situation knowledge.. We assessed four facets of EK: emotion recognition knowledge (identifying emotions, but not necessarily naming them), expressive emotion knowledge (generating emotion words), emotion situation knowledge (understanding how someone would likely feel in a given situation), and behavioral emotion knowledge (identifying how someone is feeling based on multiple behavioral emotion cues). Each EK domain is described below.

Emotion Recognition Knowledge

Three tasks were used to assess children’s ability to recognize emotions. For the AKT and EMT assessments, we focused on the emotions Happy, Sad, Mad/Angry, and Scared, as these are the most commonly assessed at this age and are typically the first aspects of emotion knowledge to emerge during the preschool years (Denham, 1986). Using the EMT, children were shown a photo of a child posing a given facial expression of emotion and asked to indicate “which child feels the same way” from a panel of photos of four other children posing facial expressions of emotion (one of which was the target expression). A score was computed to indicate number of items correct (10 items, α = .54). Children were also asked to show which child in a different panel of four children feels a target emotion (e.g., “show me the one who feels happy”). A score was computed to indicate number of items correct (12 items, α = .66). Using drawn feeling faces depicting happy, sad, angry, or scared from the AKT, children were asked to identify the stated emotion. Following Denham (1986), a total score was computed: responses were scored 0 if incorrect, 1 if only the correct valence was given (e.g., “sad” for “angry”), and 2 if correct (4 items, α = .62). The standardized mean of these three scores was used to indicate Emotion Recognition Knowledge (α = .70).

Expressive Emotion Knowledge

Three tasks were used to assess children’s ability to generate emotion words. Using EMT photos, children were asked to verbally state the emotion (Happy, Sad, Mad/Angry, or Scared) that each child in a panel of four was feeling. A score was computed to indicate number of items correct (8 items, α = .72). Using the four drawn feeling faces, children were asked to identify each of the emotions depicted, using words, and responses were scored as for the Denham tasks (0 if incorrect, 1 for correct valence, 2 if correct; 4 items, α = .48). Children were also asked to “name all the different feeling words you can think of,” based on the KAI (Kusché et al., 1988). A total score indicated the number of emotion words the child generated. The standardized mean of these three scores was used to indicate Expressive Emotion Knowledge (α = .71).

Emotion Situation Knowledge

In these sections of the interview, as well as above, interviewers were instructed not to give any behavioral cues in order to assess whether children could report emotional responses to different situations based on situational cues alone. Using EMT photos, children were asked to indicate the face of the child who had just experienced an emotion-eliciting event (e.g., “show me the one who just got a nice new toy”), and a score was computed indicating the number of correct responses (9 items; α = .57). Children were also read 8 vignettes from the AKT that typically evoke particular common emotions (e.g., “Susie got an ice-cream cone; how is she feeling?”; Garner, Jones, & Miner, 1994), and asked to identify how the character in the story felt. Responses were scored as for the Denham tasks (0 if incorrect, 1 for correct valence, 2 if correct; 6 items, α = .55). As others have also found (e.g., Schultz, Izard, & Ackerman, 2000), excluding the mad/angry items resulted in significant improvement in the reliability of the scales, thus, we excluded these items from the Emotion Situation Knowledge scales in the current study. The standardized mean of the AKT and EMT scales was calculated to indicate overall Emotion Situation Knowledge (α = .61).

Behavioral Emotion Knowledge

Finally, children’s ability to understand how others are feeling by reading behavioral cues about emotion was assessed. We used a slightly adapted version of the AKT to assess behavioral emotion knowledge (Miller, Fine, Gouley, Seifer, & Dickstein, 2006). In this portion of the protocol, interviewers used puppets from the AKT and emphasized behavioral emotion cues (i.e., vocal and facial expressions) to enact stories depicting 8 situations in which the main character likely would experience happiness, sadness, anger, or fear. At the end of each story, children were asked to identify how they thought the protagonist felt. Responses were scored as for the Denham tasks (0 if incorrect, 1 for correct valence, 2 if correct), and yielded a standardized score for Behavioral Emotion Knowledge (8 items, α = .73).

Child Outcomes

We assessed children’s negative social-emotional experiences in preschool using reports from multiple sources: children, teachers, peers, and parents. Because relatively few studies have examined EK in relation to such processes at this age (Trentacosta & Fine, 2010), we asked children directly about their experiences of loneliness, peer exclusion, victimization, and social rejection at school; asked peers and teachers about the child’s social functioning; and asked parents to report on child internalizing symptoms.

Child-Reported Social-Emotional Experiences

After the EK interview, children were interviewed regarding their social-emotional experiences in school, specifically victimization, rejection, and loneliness. Children were first given practice items to rate (e.g., “I have toast for breakfast”) using the 3-point response scale (1 = no, 2 = sometimes, 3 = yes) to make sure they understood the process. Victimization items were based on the Perceptions of Peer Support Scale (e.g., “do you get picked on”; 5 items; α = .77; Kochenderfer & Ladd, 1996). The Rejection scale (e.g., “do kids tell you they don’t like you”; 9 items; α = .74) was based on previous work (Asher, Rose, & Gabriel, 2001), as was the Loneliness scale (e.g., “is school a lonely place”; 8 items; α = .76; Burgess et al., 1999; Cassidy & Asher, 1992). Scales had all been used with children in the fall of their kindergarten year, where children were in our age range (5.5 years; Kochenderfer & Ladd, 1996, Buhs & Ladd, 2001). Because victimization and rejection were highly correlated and often co-occur, we combined them to form a victimization/rejection scale (14 items, α = .85).

Teacher-Reported Social Functioning

Teachers responded to three questions regarding the extent to which children were liked or disliked by peers (e.g., “most children would say this is one of the 3 children in class they like the most”; adapted from Fabes & Eisenberg, 1992). Responses were coded to reflect negative ratings and summed to create a negative teacher rating variable (3 items, α = .72).

Peer-Reported Social Functioning

Children’s classmates were also briefly interviewed to assess peer reports of child social functioning, as has been done in prior research with children this age (Buhs & Ladd, 2001). Using class photos as a visual aid, children in the classroom were individually asked to name children in their class who they liked least, and who play alone/not with other kids. Following Buhs & Ladd (2001), responses were coded to reflect negative ratings, summed and averaged to create a negative peer nomination variable.

Parent-Reported Internalizing

As part of the larger study, children’s parents completed the 100-item Child Behavior Checklist normed for our age group (CBCL 1 ½ - 5; Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001), which yields a standardized score for Internalizing symptoms (e.g., “afraid to try new things”; α =.76; Rescorla, 2005). Only the Internalizing subscale was used for the purposes of the current investigation.

Statistical Analysis

We conducted a series of hierarchical regression analyses to assess the respective contributions of each type of EK to child-reported social experiences of victimization, rejection, and loneliness in school; to teacher- and peer-reported social functioning; and to parent-reported internalizing symptoms. Each outcome was first regressed on each EK predictor separately (20 models in total), followed by five models regressing each outcome of the four EK variables together to parse out the unique versus shared effects of the EK predictors. For each analysis, we also examined the contribution of child age, sex, race (white versus non-white), income to needs ratio and language skill. When examining EK predictors separately, all five covariates were first entered into a regression equation (step 1), followed by an equation that included both the covariates and EK predictor (step 2). Finally, we added a predictor-sex interaction term (step 3) to test for changes in the predictor-criterion association based on child sex. For the combined models, covariates were included as above (step 1), followed by an equation including both the covariates and all four EK predictors (step 2). Step 3 added four EK-sex interaction terms as well as a sex-age interaction. In each analysis, boys served as the reference category. To control for the number of hypotheses tested, we adjusted the F-test using a Bonferonni correction in each regression (Schaffer, 1995).

Results

Means and standard deviations of all variables are reported in Table 1 by sex as well as overall. Only two variables showed initial mean differences by sex. Overall, boys had higher income-to-needs ratios and were more likely to receive a negative teacher nomination than girls. Initial analyses indicated that correlations between predictors were small to moderate (see Table 2), suggesting no multicollinearity (Cohen, Cohen, West & Aiken, 2003). There were no associations between sex and EK, and age was associated with only two of the EK facets. Language, as expected, was positively associated with all EK facets. Child self-reported loneliness was not related to parent-, teacher-, or peer-related outcomes, but self-reported victimization/rejection was related to negative peer nominations.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics by Sex

| Boys | Girls | Overall | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Emotion Recognition Knowledge | −.08 (.53) | .10 (.55) | −.01 (.60) |

| 2. Expressive Emotion Knowledge | −.02 (.66) | .02 (.77) | .01 (.71) |

| 3. Emotion Situation Knowledge | −.04 (.43) | .06 (.42) | .00 (.44) |

| 4. Behavioral Emotion Knowledge | 1.69 (.34) | 1.72 (.30) | 1.71 (.32) |

| 5. Loneliness | 1.42 (.46) | 1.48 (.48) | 1.45 (.46) |

| 6. Victimization /Rejection | 1.65 (.49) | 1.72 (.49) | 1.69 (.49) |

| 7. Teacher Negative Nominations | 1.88 (.84) | 1.67 (.70)* | 1.78 (.77) |

| 8. Parent Internalizing | 48.51 (10.01) | 47.57 (12.13) | 47.98 (11.23) |

| 9. Peer Negative Nominations | 1.37 (1.55) | .91 (.92) | 1.12 (1.26) |

| 10. Age (years) | 4.98 (.29) | 5.00 (.28) | 4.99 (.28) |

| 11. Language Ability | 96.07 (13.16) | 99.49 (14.01) | 97.95 (13.69) |

| 12. Race (% Non-White) | 25% | 22% | 23% |

| 13. Income to Needs Ratio | 1.26 (.88) | 1.17 (.63)* | 1.21 (.76) |

Note. Two-tailed tests of mean difference between boys and girls indicated by asterisks. Standard deviations are in parentheses.

p < .05.

Table 2.

Correlations Among Independent, Dependent and Control Variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Emotion Recognition Knowledge | 1 | ||||||||||||

| 2. Expressive Emotion Knowledge | .38** | 1 | |||||||||||

| 3. Emotion Situation Knowledge | .34** | .55** | 1 | ||||||||||

| 4. Behavioral Emotion Knowledge | .33** | .52** | .56** | 1 | |||||||||

| 5. Loneliness | −.19* | −.15 | −.13 | −.29** | 1 | ||||||||

| 6. Victimization /Rejection | −.01 | −.09 | −.14 | −.21* | .54** | 1 | |||||||

| 7. Teacher Negative Nominations | −.06 | −.01 | −.04 | .03 | .08 | .11 | 1 | ||||||

| 8. Parent Internalizing | −.13 | −.20* | −.21* | −.03 | .12 | .17 | .42** | 1 | |||||

| 9. Peer Negative Nominations | −.07 | .13 | .15 | −.01 | .18* | .15 | .34** | .30** | 1 | ||||

| 10. Sex | .16 | .03 | .12 | .04 | .06 | .08 | −.14 | −.04 | −.18* | 1 | |||

| 11. Age | .10 | .09 | .19* | .18* | −.21* | −.12 | −.22* | −.20* | −.14 | .03 | 1 | ||

| 12. Language Ability | .31** | .46** | .46** | .29** | −.20* | −.03 | −.12 | −.27** | .05 | .13 | −.09 | 1 | |

| 13. Race | .07 | .01 | −.09 | −.07 | .05 | .04 | −.13 | .05 | .17 | −.04 | −.15 | −.01 | 1 |

| 14. Income to Needs | −.03 | .03 | .27** | .01 | .05 | −.05 | −.08 | −.05 | .11 | −.06 | .10 | .10 | .02 |

Note.

p < .05,

p < .01 (two-tailed).

Emotion Recognition Knowledge

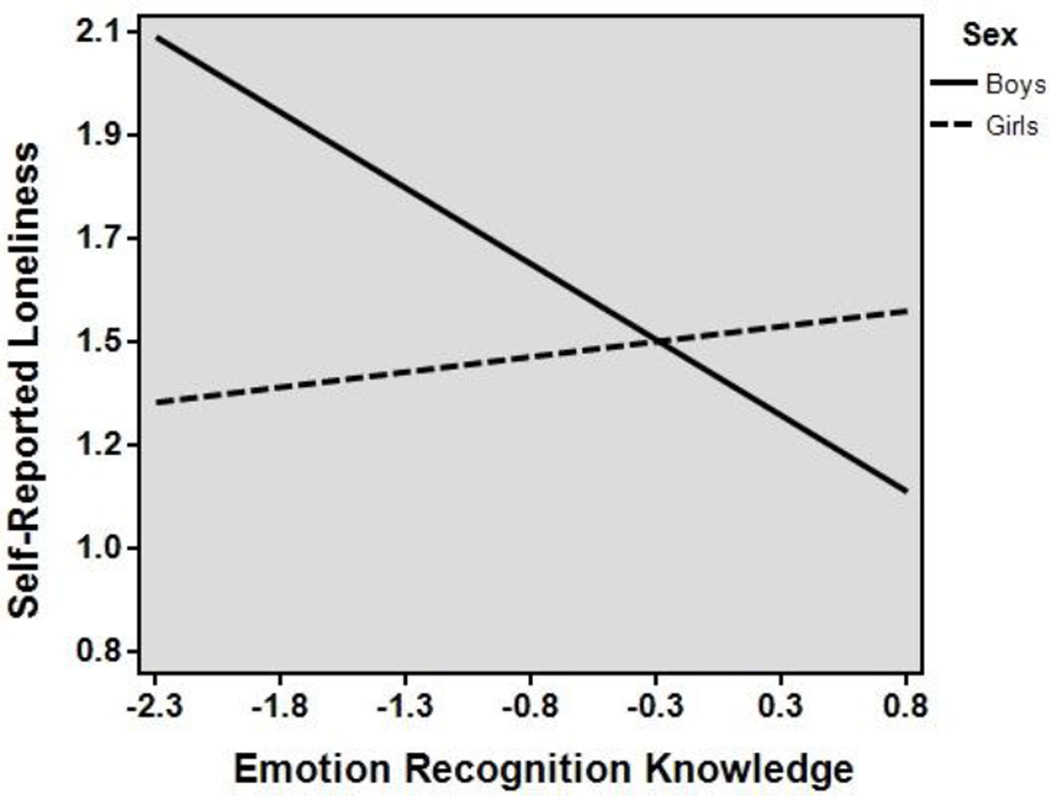

Emotion recognition knowledge, or the ability to recognize emotions without the aid of verbal or contextual cues, was a significant predictor of loneliness, though only when accounting for a recognition-by-sex interaction (see Table 3). As seen in Figure 1, boys with higher emotion recognition skills were less likely to report loneliness (βboys = −.31, t = −2.63, p < .01), although the same was not true for girls, whose level of loneliness remained relatively stable regardless of their emotion recognition ability (βgirls = .06, t = 0.63, ns). Emotion recognition was not a significant predictor of self-reported victimization/rejection, negative teacher or peer nominations, or parent-reported internalizing symptoms.

Table 3.

Emotion Recognition Knowledge

| Predictor | Self-Reported Internalizing Problems | Other Reported Internalizing Problems | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Loneliness | Victimization and Rejection |

Teacher Negative Nominations |

Parent Internalizing | Peer Negative Nominations |

||||||||||||

| β | β | β | β | β | ||||||||||||

| Step 1: Covariates |

Sex | .08 | .10 | .10 | .10 | .10 | .10 | −.08 | −.09 | −.09 | .01 | .01 | .01 | −.15 | −.14 | −.14 |

| Age | −.24** | −.23* | −.21* | −.15 | −.15 | −.15 | −.26** | −.26** | −.26** | −.25** | −.25** | −.24** | −.13 | −.12 | −.13 | |

| Language | −.27** | −.23* | −.19* | −.06 | −.06 | −.06 | −.15 | −.16 | −.15 | −.29** | −.29** | −.31** | .03 | .05 | .03 | |

| Income/Needs | .12 | .11 | .08 | −.02 | −.02 | −.02 | −.04 | −.04 | −.04 | .02 | .02 | .03 | .11 | .10 | .12 | |

| Race | .00 | .02 | .01 | .02 | .02 | .02 | −.16 | −.16 | −.16 | −.03 | −.02 | −.02 | .13 | .14 | .15 | |

| Step 2: Emotion Knowledge Predictor |

Emotion Recognition Knowledge |

−.11 | −.37** | .02 | .01 | .04 | .02 | −.02 | 0.17 | −.06 | .10 | |||||

| Step 3: EK by Sex Interaction |

Emotion Recognition X Sex |

.33** | .02 | .02 | −.23 | −.19 | ||||||||||

| Model F | 3.07b | 2.77b | 3.37** | .78 | .65 | .56 | 2.97b | 2.48 | 2.11 | 3.29** | 2.73b | 2.67b | 2.00 | 1.72 | 1.77 | |

| Model R2 | .12 | .13 | .17 | .03 | .03 | .03 | .11 | .11 | .11 | .13 | .13 | .14 | .08 | .08 | .10 | |

| Change in R2 | .01 | .05* | .00 | .00 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.02 | .00 | .02 | ||||||

Note.

p < .05,

p < .016,

p < .01.

Figure 1.

Association between emotion recognition knowledge and self-reported loneliness in boys and girls. Higher values indicate more feelings of loneliness.

Expressive Emotion Knowledge

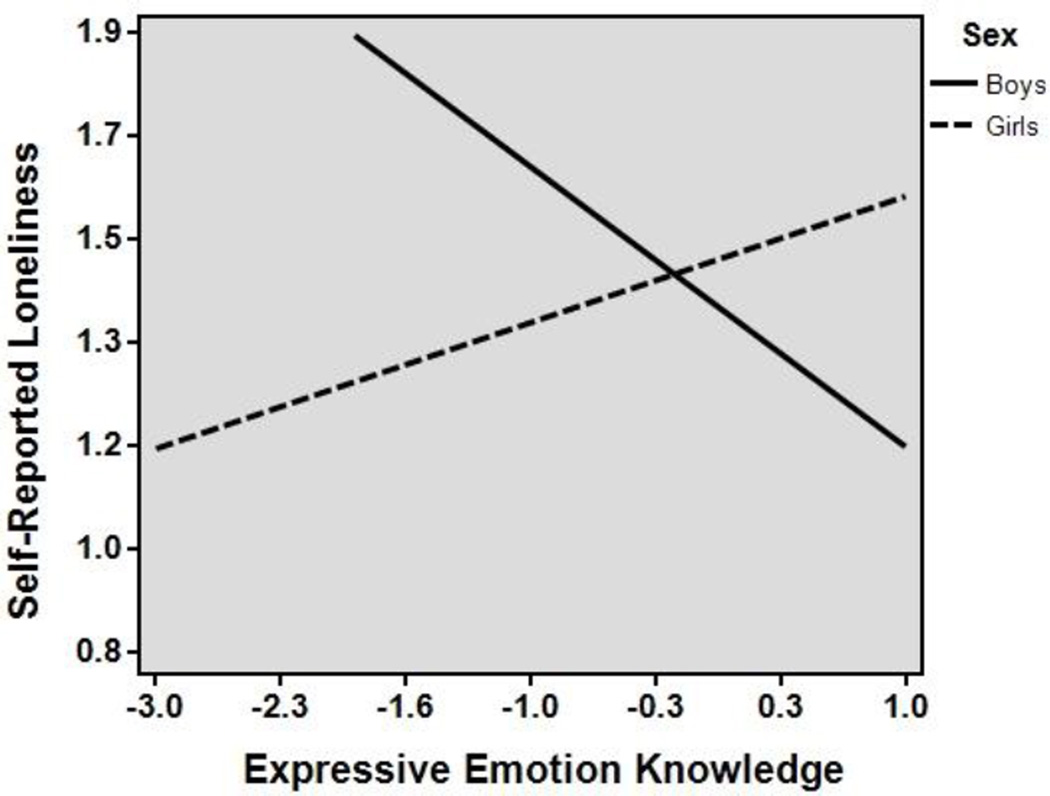

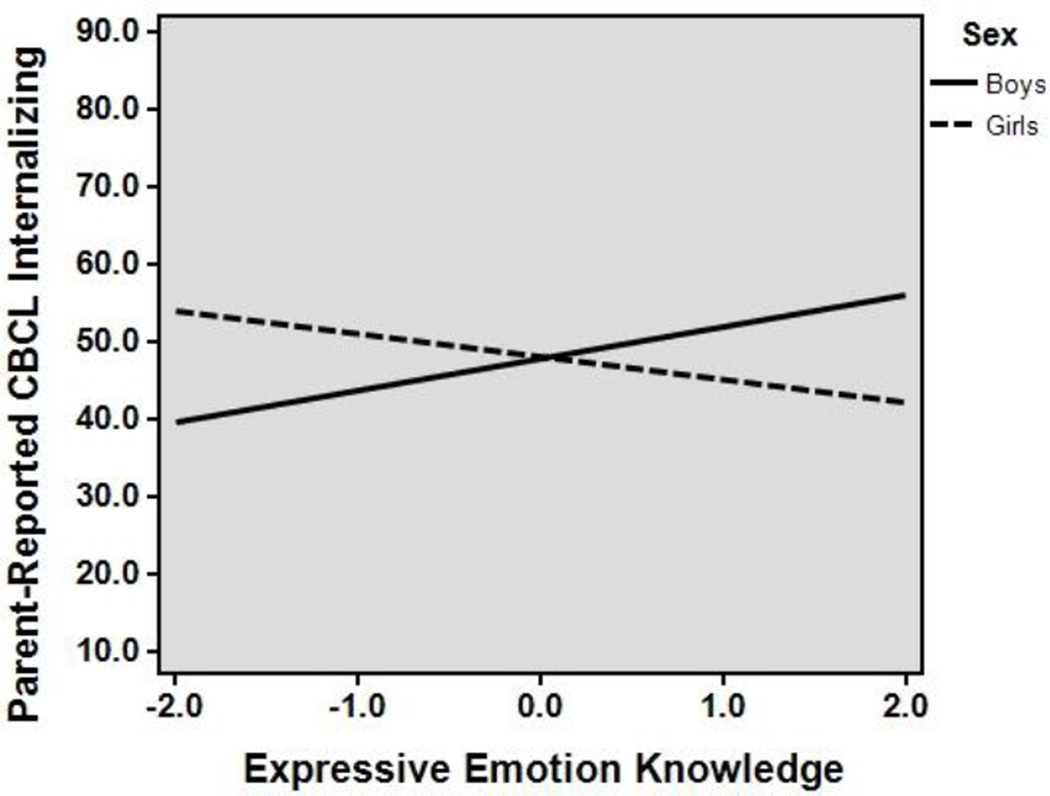

Expressive EK, or the ability to generate emotion words, also predicted loneliness (see Table 4). Expressive emotion knowledge was negatively associated with loneliness, but was qualified by an expressive EK-by-sex interaction. As seen in Figure 2, boys who knew more emotion words tended to report less loneliness (βboys = −.23, t = −2.50, p < .01). The expressive EK-loneliness association was not significant for girls (βgirls = .10, t = 1.43). The expressive EK-by-sex interaction also emerged as a predictor of parent-reported internalizing symptoms. Examination of the simple slopes indicated that girls who knew more emotion words had fewer parent-reported internalizing symptoms (βgirls = −.11, t = −1.65, p = .10; two-tailed). The slope for boys did not reach significance (βboys = .26, t = 1.61, p = .11) (Figure 3).

Table 4.

Expressive Emotion Knowledge

| Predictor | Self-Reported Internalizing Problems | Other Reported Internalizing Problems | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Loneliness | Victimization and Rejection |

Teacher Negative Nominations |

Parent Internalizing | Peer Negative Nominations |

||||||||||||

| β | β | β | β | β | ||||||||||||

| Step 1: Covariates |

Sex | .08 | .08 | .09 | .10 | .10 | .10 | −.08 | −.08 | −.08 | .01 | .00 | .01 | −.15 | −.14 | −.14 |

| Age | −.24** | −.24* | −.21* | −.15 | −.13 | −.13 | −.26** | −.27** | −.28** | −.25** | −.24** | −.26** | −.13 | −.16 | −.17 | |

| Language | −.27** | −.25* | −.26* | −.06 | −.02 | −.02 | −.15 | −.19 | −.18 | −.29** | −.27** | −.26* | .03 | −.06 | −.06 | |

| Income/Needs | .12 | .12 | .10 | −.02 | −.02 | −.02 | −.04 | −.04 | −.02 | .02 | .02 | .03 | .11 | .12 | .12 | |

| Race | .00 | .01 | .00 | .02 | .03 | .03 | −.16 | −.16 | −.16 | −.03 | −.02 | −.03 | .13 | .13 | .13 | |

| Step 2: Emotion Knowledge Predictor |

Expressive Emotion Knowledge |

−.03 | −.37** | −.09 | −.10 | .09 | .30* | −.05 | .26 | .17 | .34* | |||||

| Step 3: EK by Sex Interaction |

Emotion Recognition X Sex |

.43** | .02 | −.27 | −.38* | −.20 | ||||||||||

| Model F | 3.07b | 2.55 | 3.65** | .78 | .76 | .65 | 2.97b | 2.61 | 2.78** | 3.29** | 2.76b | 3.29** | 2.00 | 2.25 | 2.21 | |

| Model R2 | .12 | .12 | .14 | .03 | .04 | .04 | .11 | .12 | .14 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.17 | .08 | .11 | .12 | |

| Change in R2 | .00 | .07** | .01 | .00 | .01 | .03 | 0 | .04* | .03 | .02 | ||||||

Note.

p < .05,

p < .016,

p < .01.

Figure 2.

Association between expressive emotion knowledge and self-reported loneliness in boys and girls. Higher values indicate more feelings of loneliness.

Figure 3.

Association between expressive emotion knowledge and parent-reported internalizing in boys and girls. Higher values indicate more internalizing behaviors.

Expressive EK was not associated with self-reported victimization/rejection or teacher and peer negative nominations.

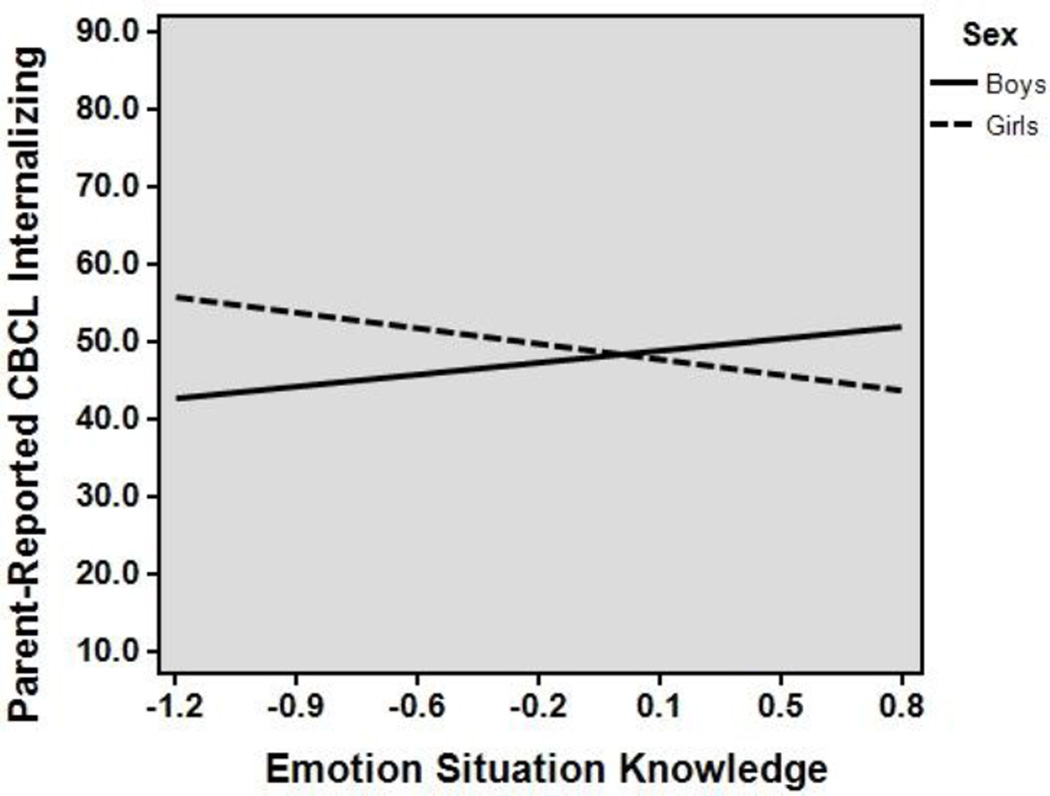

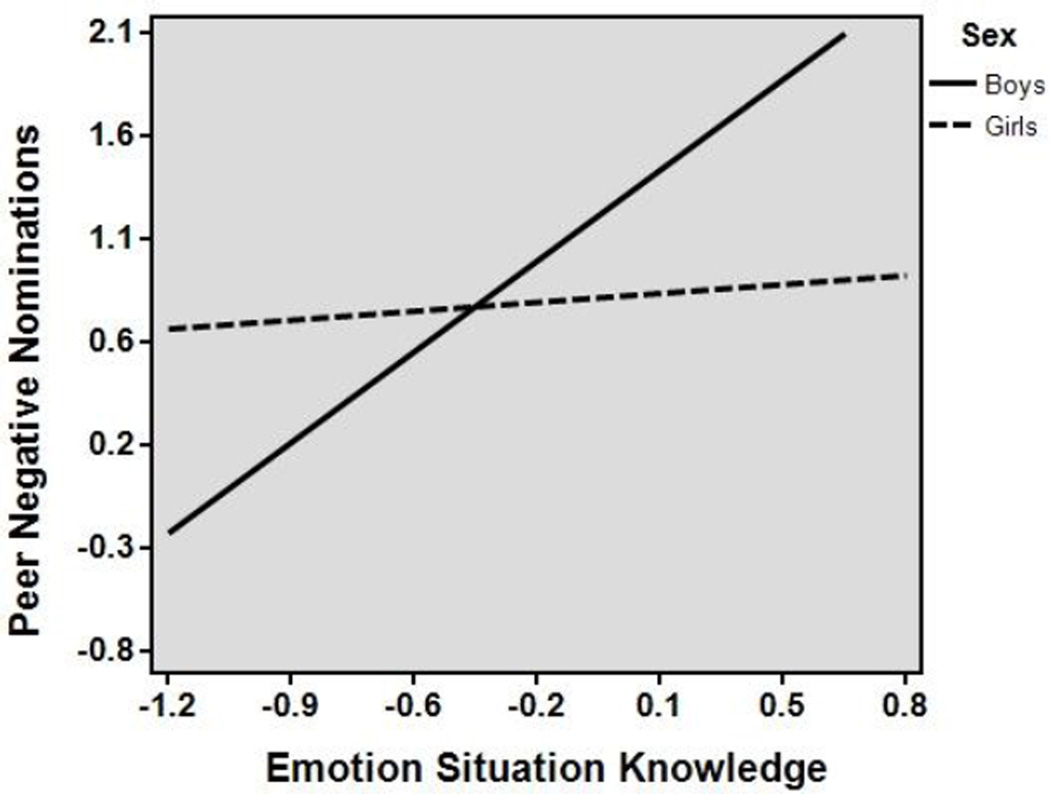

Emotion Situation Knowledge

Emotion situation knowledge, or understanding how someone would likely feel in a given situation, was not associated with self-reported loneliness or victimization/rejection, or negative teacher nominations (Table 5). A significant emotion situation knowledge-by-sex interaction emerged for parent-reported internalizing symptoms. As seen in Figure 4, girls with greater emotion situation knowledge tended to have fewer parent-reported internalizing symptoms (βgirls = −.12, t = −1.68, p = .10; two-tailed). The simple slope was not significant for boys (βboys = .17, t = 1.23). The emotion situation knowledge-by-sex interaction also predicted negative peer nominations. As seen in Figure 5, relative to girls, boys with more emotion situation knowledge received more negative nominations from their peers (βboys= .43, t = 3.08, p < .01). The association for girls was not significant (βgirls = .15, t = 0.32).

Table 5.

Emotion Situation Knowledge

| Predictor | Self-Reported Internalizing Problems | Other Reported Internalizing Problems | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Loneliness | Victimization and Rejection |

Teacher Negative Nominations |

Parent Internalizing | Peer Negative Nominations |

||||||||||||

| β | β | β | β | β | ||||||||||||

| Step 1: Covariates |

Sex | .08 | .09 | .09 | .10 | .11 | .11 | −.08 | −.09 | −.09 | .01 | .01 | .01 | −.15 | −.16 | −.17 |

| Age | −.24** | −.23** | −.23** | −.15 | −.10 | −.10 | −.26** | −.29** | −.29** | −.25** | −.24* | −.23* | −.13 | −.17 | −.17 | |

| Language | −.27** | −.24* | −.24* | −.06 | .03 | .04 | −.15 | −.21* | −.21* | −.29** | −.28** | −.26** | .03 | −.06 | −.05 | |

| Income/Needs | .12 | .14 | .14 | −.02 | .03 | .02 | −.04 | −.07 | −.07 | .02 | .03 | .02 | .11 | .06 | .05 | |

| Race | .00 | .00 | .00 | .02 | .01 | .00 | −.16 | −.15 | −.15 | −.03 | −.03 | −.04 | .13 | .15 | .13 | |

| Step 2: Emotion Knowledge Predictor |

Emotion Situation Knowledge |

−.07 | −.11 | −.21 | −.05 | .14 | .10 | −.04 | .17 | .22 | .43** | |||||

| Step 3: EK by Sex Interaction |

Emotion Recognition X Sex |

.05 | −.21 | .06 | −.29* | −.29* | ||||||||||

| Model F | 3.07b | 2.62 | 2.25 | .78 | 1.25 | 1.44 | 2.97b | 2.81b | 2.43 | 3.29** | 2.74b | 3.16** | 2.00 | 2.45 | 2.87** | |

| Model R2 | .12 | .12 | .12 | .03 | .06 | .08 | .11 | .12 | .13 | .13 | .13 | .16 | .08 | .11 | .15 | |

| Change in R2 | .00 | .00 | .03 | .02 | .01 | 0 | 0 | .04* | .04* | .04* | ||||||

Note.

p < .05,

p < .016,

p < .01.

Figure 4.

Association between emotion situation knowledge and parent-reported internalizing in boys and girls. Higher values indicate more internalizing behaviors.

Figure 5.

Association between emotion situation knowledge and peer negative nominations in boys and girls. Higher values indicate more negative nominations.

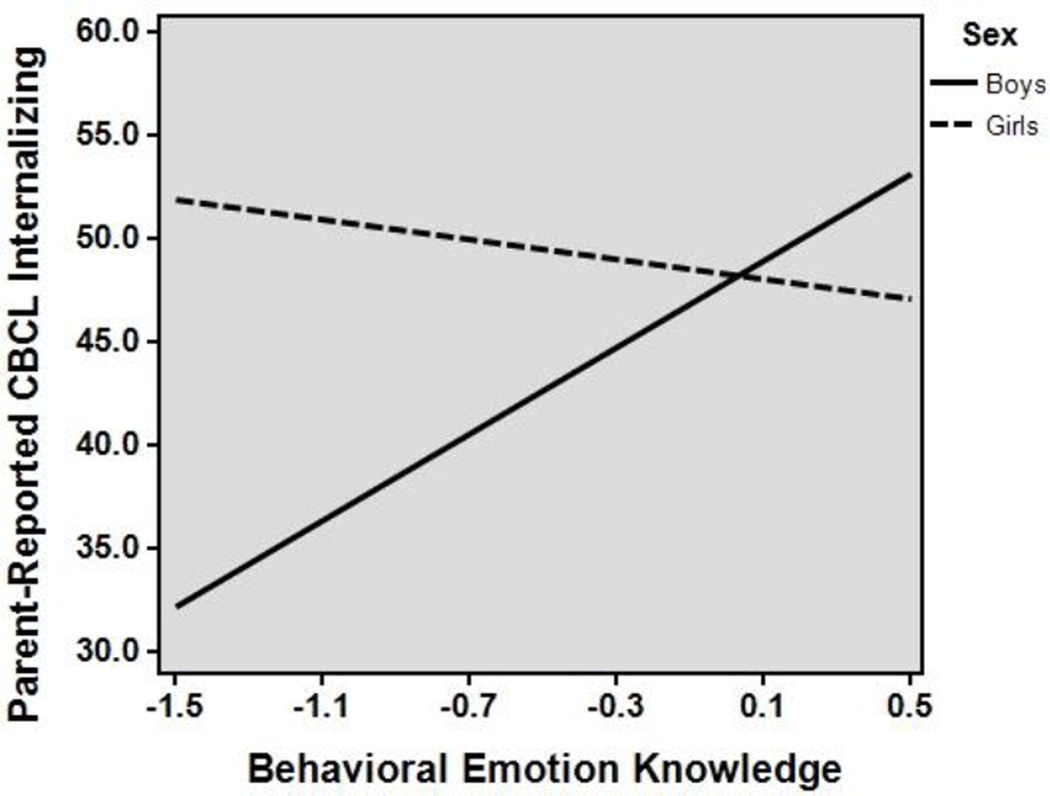

Behavioral Emotion Knowledge

Children’s behavioral EK, or understanding of emotions based on behavioral cues, was negatively associated with both loneliness and victimization/rejection (see Table 6). Models including covariates and the behavioral EK-by-sex interaction were not significant. A significant behavioral EK-by-sex interaction emerged for the association between behavioral EK and parent-reported internalizing. As seen in Figure 6, boys with higher behavioral EK tended to have higher parent-reported internalizing symptoms (βboys = .29, t = 2.24, p < .05). The simple slope for girls was not significantly different from zero (βgirls = −.03, t = −0.55). Behavioral EK was not related to either peer or teacher negative nominations.

Table 6.

Behavioral Emotion Knowledge

| Predictor | Self-Reported Internalizing Problems | Other Reported Internalizing Problems | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Loneliness | Victimization and Rejection |

Teacher Negative Nominations |

Parent Internalizing | Peer Negative Nominations |

||||||||||||

| B | β | β | β | β | ||||||||||||

| Step 1: Covariates |

Sex | .08 | .08 | .08 | .10 | .09 | .09 | −.08 | −.08 | −.08 | .01 | .01 | .02 | −.15 | −.15 | −.15 |

| Age | −.24** | −.20** | −.19* | −.15 | −.10 | −.11 | −.26** | −.29** | −.29** | −.25** | −.27** | −.28** | −.13 | −.13 | −.14 | |

| Language | −.27** | −.21* | −.21* | −.06 | −.00 | .00 | −.15 | −.19* | −.19* | −.29** | −.32** | −.32** | .03 | .02 | .02 | |

| Income/Needs | .12 | .11 | .11 | −.02 | −.02 | −.01 | −.04 | −.03 | −.03 | .02 | .02 | .05 | .11 | .11 | .12 | |

| Race | .00 | −.01 | −.01 | .02 | .01 | .01 | −.16 | −.16 | −.16 | −.03 | −.03 | −.03 | .13 | .14 | .13 | |

| Step 2: Emotion Knowledge Predictor |

Behavioral Emotion Knowledge |

−.21* | −.27* | −.20* | −.09 | .14 | .15 | .10 | .29* | .02 | .12 | |||||

| Step 3: EK by Sex Interaction |

Emotion Recognition X Sex |

.09 | −.15 | .00 | −.26* | −.14 | ||||||||||

| Model F | 3.07b | 3.51** | 3.06** | .78 | 1.35 | 1.35 | 2.97b | 2.92b | 2.48 | 3.29** | 2.93b | 3.20** | 2.00 | 1.66 | 1.59 | |

| Model R2 | .12 | .16 | .16 | .03 | .07 | .08 | .11 | .13 | .13 | .13 | .13 | 0.17 | .08 | .08 | .09 | |

| Change in R2 | .04* | .00 | .03* | .01 | .02 | 0 | 0 | .04* | .00 | .01 | ||||||

Note.

p < .05,

p < .016,

p < .01.

Figure 6.

Association between behavioral emotion knowledge and parent-reported internalizing in boys and girls. Higher values indicate more internalizing behaviors.

Combined Emotion Knowledge Model

When all four EK variables and their interaction terms were jointly included in steps 2 and 3, respectively, we found some changes in the associations between the EK predictors and both the parent internalizing and victimization and rejection outcomes, but not for the other outcomes. The EK x sex interactions that had significant associations with parent-reported internalizing symptoms (emotion situation knowledge; expressive emotion knowledge; behavioral emotion knowledge) were no longer uniquely significant when entered into a regression equation together, suggesting that the EK predictor by sex interactions explained overlapping variance in the outcome. In addition, the main effect for behavioral emotion knowledge as a predictor of self-reported victimization and rejection was no longer significant after controlling for other EK facets. In contrast, the strength and direction of the associations between EK predictors (and their sex interactions) and loneliness, teacher negative nominations and peer negative nominations were unchanged after including additional EK facets in the model.

Discussion

We examined multiple facets of EK in relation to internalizing symptoms and early social-emotional experiences – specifically loneliness, victimization, and peer rejection. Although certain EK skills (particularly EK recognition and expression) were associated with more positive social functioning, findings for other EK skills were mixed. There were important qualifications by sex, type of social outcome examined, and whether the outcome was reported by the child or another informant. Most facets of EK were related to self-reported feelings of loneliness, whereas only a few were predictive of perceived social rejection/victimization, or peer, teacher or parent evaluations. The sex differences that moderated the association between EK and the outcomes of interest may coincide with emerging sex differences in play and socialization during the preschool years.

Facets of Emotion Knowledge

Previous work on EK has typically not focused on understanding the association of different facets of EK with child outcomes, but rather examined EK as a single construct. Our measures of EK were moderately inter-correlated (r’s ranged from .28 to .54), which is consistent with the relatively few studies that have also assessed multiple facets of EK (e.g., Bassett et al., 2012; Garner & Waajid, 2012; Miller et al., 2005). Emotion recognition, or the ability to recognize static emotion faces, was the least strongly associated with EK facets that depended on a child’s ability to read social context cues (i.e., situation emotion knowledge or behavioral emotion knowledge). This is consistent with others who have proposed a 2-factor model of EK, with emotion recognition as one factor and the other emotion situation knowledge (behavioral emotion knowledge was not considered; Bassett et al., 2012). Emotion recognition and expression skills typically emerge earlier in development than situation knowledge, and indeed we found that age was positively associated with the more advanced EK facets we assessed (situation and behavioral knowledge). The fact that we and others (e.g., Garner & Waajid, 2012; Miller et al., 2005) have also found differential associations among EK facets and child outcomes suggests that there may be unique roles of each facet of EK for child social functioning, at least in the preschool peer setting. A notable exception in the present study may be the associations between EK and parent-reported internalizing symptoms. When examined separately, three EK by sex interactions predicted parent-reported internalizing, yet no associations were significant when the EK variables were included together in the model. This finding suggests a certain amount of overlap among EK skills as viewed by parents. Parents, who may have richer exposure to their children’s functioning across many situations, may not consider the potentially distinctive role of EK skills in relation to their children’s social behavior, instead primarily considering EK as a unified construct encompassing multiple skills. Thus, although facets of EK overlap, certain skills may be most critical for positive social relationships with peers. It is important to assess whether children have mastered each type of EK skill across the preschool period, when these skills are rapidly developing and when EK-focused interventions may be most effective.

In this study, we utilized multiple measures of EK to determine if different EK facets were differentially related to negative school experiences. Consistent with our prediction, children with poor EK skills consistently experienced greater loneliness and social rejection. Different patterns of association suggest that we might be able to improve or tailor our efforts to intervene with children who are having difficulties in this area. For example, poorer EK recognition and expression skills and poorer behavioral EK were consistently associated with child-reported loneliness, but emotion situation knowledge was more closely related to peers’ reports of whether or not they would want to play with the child. This finding has implications for working with children who are feeling lonely or rejected by peers and not very socially engaged. For these children, it may be important to focus not only on basic naming and recognition skills (perhaps internalizing emotions like sad, anxious, or lonely) but also on behavioral EK skills that require accurate “reading” of cues such as facial expression and body language as they occur in real time. Supporting this finding, a recent study of children slightly younger than those in the current study found that identifying the appropriate behavioral responses to an emotion situation was associated with less parent-reported anxiety, whereas false-belief understanding, which assesses a more static understanding of mental states (similar to a more static understanding of emotion words), was not associated (Denault & Ricard, 2013). In contrast, emotion situation knowledge may be somewhat more important to focus on when working with children who are socially engaged, but perhaps not skilled in recognizing situational predictors of others’ emotional states (e.g., a child who does not realize that another child may feel sad if a toy is taken away). Garner & Waajid (2012) found that emotion situation knowledge, rather than more “basic” emotion recognition skill, was related to both cognitive and social outcomes in preschool-age children, whereas Miller et al. (2005) found that recognition, versus expression of emotions, was more predictive of peer social functioning among older children (situation knowledge was not assessed). Understanding how each facet of EK is important for different aspects of social functioning and how to work with children who are experiencing different types of social difficulties may be helpful for interventionists who wish to maximize the effectiveness of their lesson time with children. For example, it may be effective to have children practice identifying and labeling emotion expressions as they occur in an interactional role play context. It may not be sufficient to teach children emotion vocabulary words without also encouraging them to recognize these emotions as they “play out” in real time and in situations resembling those they may encounter during the preschool day.

Multiple Informants

The use of multiple informants added greater depth to our understanding of the relationship between EK and early school experience. Results highlight an important discrepancy between individual- and other-reported evaluations with regard to assessing internalizing-relevant social-emotional experiences. Most research on EK skills and social outcomes in preschool relies on teacher-reported child functioning. Talking to teachers alone may not give us a complete understanding of children’s experiences, particularly with regard to feelings of loneliness, perceived social rejection or peer victimization. Preschool-age children in the current study were asked about such experiences in one-on-one interviews. It may be important to use this method in evaluations of EK-focused interventions. Victimization and peer rejection during the preschool years are reliable predictors of later peer problems and school difficulties (Ladd, Birch, & Buhs, 1999; Ladd, Kochenderfer, & Coleman, 1996) and are thus important to identify and address early on. Children who are lonely and victimized by peers may also experience higher rates of bullying, and in turn bully others (Kaltiala-Heino, Rimpela, Rantanen, & Rimpela, 2000). Thus, it is vital to assess children directly and to supplement their reports with reports from others, as teachers are clearly critical socializers of early child emotional competence (Denham, Bassett, & Zinsser, 2012). Future research could investigate whether identifying discrepancies between teacher- and child-reports of internalizing-relevant outcomes provides an opportunity to improve young children’s classroom experiences and later social outcomes.

Sex and Age Effects

Although there were no significant differences in EK skills by sex, sex moderated most of the associations between EK and social functioning. Among boys, more basic EK recognition and expressive skills were associated with less self-reported loneliness, but more complex EK skills (situation knowledge and behavioral knowledge) were associated with poorer functioning as reported by others (greater parent-reported internalizing symptoms, more negative peer nominations). This suggests that for boys, basic EK skills may be important for managing internal feeling states, but that the role of EK in social interactions may be different. Such findings are not unprecedented. For example, Garner and Lemerise (2007) found negative associations between emotion situation knowledge and peer physical victimization, which is a common element of preschool boys’ play behavior (Ostrov & Keating, 2004). Gathering information from multiple informants, including the child, is important in order to assess all aspects of social functioning. Results also underscore the potential salience of sex roles for parents, peers, and even teachers with regard to social interactions in early childhood.

Following Dunsmore et al. (2008), it may be that EK skills play different roles with regard to social behaviors for boys versus girls. For preschool-age boys, facets of EK that involve knowledge of others’ emotion states may not always be seen by others as an ideal social profile: A boy who is highly attuned to the emotional needs or expressions of his peers may be perceived as more internalizing (e.g., withdrawn, quiet) by parents who think boys should be more “boisterous”. If such attunement prevents the boy from engaging in rough physical play or the physical conflict resolution strategies favored by boys (Miller, Danaher, & Forbes, 1986), peers may report that the child is less well-liked. Such an interpretation is consistent with research on parental socialization of emotion in low-income samples in that parents of toddlers were found to encourage boys’, but discourage girls’ expressions of anger and may generally discourage boys’ expression of internalizing emotions such as sadness (Chaplin et al., 2010). Facets of EK that require knowledge of one’s own emotions may be important for boys however, given our finding that boys with higher basic EK skills reported less loneliness, even to a somewhat greater degree than girls. During the preschool years there may be some protective effect of basic EK skills for boys’ management of their own internal emotion states. The role of EK in boys’ (and girls’) social outcomes may change with development. Among 9–13 year-olds, EK and emotion regulation mediated the association between parent emotion socialization and internalizing behavior outcomes for boys, and social skills outcomes for girls, such that children of both sexes benefited from emotion coaching most when they could identify and enact effective emotion regulation strategies (Cunningham et al., 2009).

We also found age effects for many of the outcomes we examined in the current study. Although our age range was not very large (4.5 – 5.6 years), this period represents a significant increase in the complexity of social relationships. It is important to recognize the social-emotional shifts that occur within this developmental timeframe and how they play out in classroom settings. For example, children’s abilities to reflect on or perceive loneliness may become more accurate across this age period as they gain more self-evaluative and perspective-taking capacity (Marsh & Craven, 1991). In turn this may have an impact on how they interpret social rejection or exclusion by peers. Teachers and parents tend to under-report internalizing problems for younger children (Lutz, Fantuzzo, & McDermott, 2002), and teachers’ ratings of child social functioning can vary based on children’s ages (Saft & Pianta, 2001), which may explain some of the age-related effects that emerged. The relatively consistent age findings also suggest emphasizing to early childhood educators how to identify the subtle social behaviors and experiences that may signal risk for later internalizing difficulties.

EK skills (particularly situational and behavioral EK) were also related to age. From a prevention and developmental perspective, understanding how different facets of EK develop and relate to child outcomes across a wide range of ages is important. For example, around 9–11 years, children develop the cognitive ability to engage in reappraisal, which aids in emotion regulation (Pons et al., 2004). This EK skill that develops in childhood may help reduce the likelihood of engaging in future maladaptive emotion regulation processes (e.g., rumination, negative self-appraisals) that are a core feature of many adult and adolescent internalizing disorders. Given the increase in internalizing problems that emerge for girls after puberty (Hayward & Sanborn, 2002), and that impairments in EK are associated with internalizing difficulties in female adolescents (e.g., Eastabrook, Flynn, & Hollenstein, 2013; Sim & Zeman, 2004), the pre-pubescent years may be an opportune time to provide booster interventions for girls’ EK skills. Such interventions may benefit from a focus on accurate interpretation and effective coping with negative emotions (Eastabrook et al., 2013). Importantly, EK skill training has also been shown to reduce aggression as well as enhance empathy in adolescent boys (Castillo, Salguero, Fernández-Berrocal, & Balluerka, 2013); reinforcing boys’ knowledge of emotion regulation strategies at earlier developmental periods may also prevent the externalizing behaviors that are more common among young boys. In sum, it is critical to consider developmental change, particularly when interpreting sex differences in the role of EK. The interplay between emotion socialization, emotion regulation, and emotion knowledge in relation to sex differences and adjustment over time is an area that is certainly ripe for further investigation.

Limitations

There were certain limitations in the current study. Importantly, there was an informant confound in that children reported on their EK and also their loneliness, which could have driven some of the EK-loneliness associations. Child-reported victimization/rejection was related to negative peer nominations, however, suggesting that child-reports were consistent with others’ reports. Child-reported loneliness may thus have accurately reflected children’s experience. Other methodological limitations were also present. The variables making up the peer nomination composite were also only moderately intercorrelated (r = .31), so this should be interpreted with caution. The low reliability of some of our scales, particularly our emotion situation knowledge scale was also a limitation. Though dropping the mad/angry items from emotion situation knowledge scale did not change the results of the analyses, it is interesting to consider why these items lowered the internal consistency of the scale. One explanation is that emotion situation knowledge items required children to infer an emotion from an abstract story, whereas other measures present direct stimuli (e.g. pictures). Thus, depending on the child’s interpretation of and/or personal history with the situation, children could have reasonably reported sad or mad (e.g. if their block tower were to be knocked over), which could have influenced the intercorrelation among the items. Some studies have examined anger perception accuracy as a unique aspect of emotion situation knowledge (e.g., Schultz et al., 2000), which would be interesting to explore in future research.

An additional limitation is that our relatively small sample of low-income Head Start children may not be generalizable to other populations of preschoolers. Importantly however, low-income preschoolers are important to study for multiple reasons including their increased risk for both lower EK and poorer social-emotional outcomes (Denham et al., 2012); the frequent use of EK-based interventions with low-income preschool populations (e.g., Bierman et al., 2008; Izard et al., 2004; Webster-Stratton, 2000); and the unfortunate fact that 1 in 5 children in the U.S. live in poverty (Aber, Morris, & Raver, 2012). Finally, it is also important to note that we did not have clinical levels of internalizing behavior in our sample. Thus, parents’ reports of internalizing behaviors may be more representative of personality or temperamental factors as opposed to clinical behavior problems, and findings may not generalize to children with clinical levels of internalizing problems.

Conclusion and Future Directions

Understanding nuanced associations between facets of EK, sex and the social-emotional experiences in preschool such as loneliness, peer rejection and victimization that may predict internalizing behavior may be helpful for designing and evaluating EK-based interventions for preschoolers. EK has been proposed as uniquely meaningful for internalizing problems, even above certain theory of mind skills (Denault & Ricard, 2013). Including multiple data sources (self-, peer-, teacher- and parent-reports) extends our understanding of the association between EK and these early social-emotional experiences. Classroom observations could yield further information about how EK is actually used in social interactions, which could further help shape EK-focused interventions. Future observational work could supplement measures of both EK and the outcomes of interest used in the present research. Findings support others’ calls for the inclusion of EK in interventions for preschoolers (Trentacosta & Izard, 2007), and our work highlights the differential role that EK can play for boys versus girls even during the preschool years. Finally, emotion researchers should be cognizant of the disparity between self- and other-reported internalizing outcomes. Relying on teacher reports, parent and peer perceptions, or even observations may overlook children’s internal experience, which is a critical aspect of later internalizing problems and may be shaped, in part, by EK.

Acknowledgments

FUNDING: The study was supported by K01MH066139 to Alison L. Miller and NSF-0236340 to Ronald Seifer

References

- Aber L, Morris P, Raver C. Children, families and poverty: Definitions, trends, emerging science and implications for policy. Social Policy Report: Publication of the Society for Research in Child Development. 2012 doi: 10.1002/j.2379-3988.2012.tb00072.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA. Manual for the ASEBA School-Age Forms & Profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Arsenio WF, Cooperman S, Lover A. Affective predictors of preschoolers' aggression and peer acceptance: Direct and indirect effects. Developmental Psychology. 2000;36:438–448. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asher SR, Rose AJ, Gabriel SW. Peer rejection in everyday life. In: Leary MR, editor. Interpersonal rejection. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2001. pp. 105–142. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett LF, Gross J, Christensen TC, Benvenuto M. Knowing what you're feeling and knowing what to do about it: Mapping the relation between emotion differentiation and emotion regulation. Cognition & Emotion. 2001;15:713–724. [Google Scholar]

- Bassett HH, Denham S, Mincic M, Graling K. The structure of preschoolers’ emotion knowledge: Model equivalence and validity using a structural equation modeling approach. Early Education & Development. 2012;23:259–279. [Google Scholar]

- Bierman KL, Domitrovich CE, Nix RL, Gest SD, Welsh JA, Greenberg MT, Blair C, Nelson KE, Gill S. Promoting academic and social-emotional school readiness: The Head Start REDI Program. Child Development. 2008;79:1802–1817. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01227.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody L. Sex differences in emotional development: A review of theories and research. Journal of Personality. 1985;53:102–149. [Google Scholar]

- Brown JR, Dunn J. Continuities in emotion understanding from 3–6 years. Child Development. 1996;67:789–802. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buhs ES, Ladd GW. Peer rejection as antecedent of young children’s school adjustment: An examination of mediating processes. Developmental Psychology. 2001;37:550–560. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess K, Ladd G, Kochenderfer B, Lambert S, Birch S. Loneliness during early childhood: The role of interpersonal behaviors and relationships. In: Rotenberg K, Hymel S, editors. Loneliness in childhood and adolescence. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1999. pp. 109–135. [Google Scholar]

- Carter A, Godoy L, Wagmiller R, Veliz P, Marakovitz S, Briggs-Gowan M. Internalizing trajectories in young boys and girls: The whole is not a simple sum of its parts. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2010;38:19–31. doi: 10.1007/s10802-009-9342-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy J, Asher SR. Loneliness and peer relations in young children. Child Development. 1992;63:350–365. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1992.tb01632.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castillo R, Salguero JM, Fernández-Berrocal P, Balluerka N. Effects of an emotional intelligence intervention on aggression and empathy among adolescents. Journal of Adolescence. 2013;36:883–892. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2013.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cervantes CA, Callanan MA. Labels and explanations in mother-child emotion talk: Age and gender differentiation. Developmental Psychology. 1998;34:88–98. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.34.1.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaplin TM, Casey J, Sinha R, Mayes LC. Gender differences in caregiver emotion socialization of low-income toddlers. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development. 2010:11–27. doi: 10.1002/cd.266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Cohen P, West SG, Aiken LS. Applied Multiple Regression/Correlation Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 3rd Edition. Hillsdale: NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Crick NR, Bigbee MA. Relational and overt forms of peer victimization: A multi-informant approach. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66:337–347. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.2.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham JN, Kliewer W, Garner PW. Emotion socialization, child emotion understanding and regulation, and adjustment in urban African American families: Differential associations across child gender. Development and Psychopathology. 2009;21:261–283. doi: 10.1017/S0954579409000157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deneault J, Ricard M. Are emotion and mind understanding differently linked to young children's social adjustment? Relationships between behavioral consequences of emotions, false belief, and SCBE. The Journal of Genetic Psychology. 2013;174:88–116. doi: 10.1080/00221325.2011.642028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denham SA. Social cognition, social behavior, and emotion in preschoolers: Contextual validation. Child Development. 1986;57:194–201. [Google Scholar]

- Denham SA, Bassett H, Mincic M, Kalb S, Way E, Wyatt T, Segal Y. Social- emotional learning profiles of preschoolers’ early school success: A person-centered approach. Learning and Individual Differences. 2012;22:178–189. doi: 10.1016/j.lindif.2011.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denham S, Bassett H, Zinsser K. Early childhood teachers as socializers of young children’s emotional competence. Early Childhood Education Journal. 2012;40:137–143. [Google Scholar]

- Denham SA, Blair KA, DeMulder E, Levitas J, Sawyer K, Auerbach-Major S, Queenan P. Preschool emotional competence: Pathway to social competence? Child Development. 2003;74:238–256. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denham SA, Caverly S, Schmidt M, Blair K, DeMulder E, Caal S, Hamada H, Mason T. Preschool understanding of emotions: Contributions to classroom anger and aggression. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2002;43:901–916. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denham SA, McKinley M, Couchoud EA, Holt R. Emotional and behavioral predictors of preschool peer ratings. Child Development. 1990;61:1145–1152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunsmore JC, Noguchi RJ, Garner PW, Casey EC, Bhullar N. Sex-specific linkages of affective social competence with peer relations in preschool children. Early Education & Development. 2008;19:211–237. [Google Scholar]

- Eastabrook JM, Lanteigne DM, Hollenstein T. Decoupling between physiological, self-reported, and expressed emotional responses in alexithymia. Personality and Individual Differences. 2013;55:978–982. [Google Scholar]

- Fabes RA, Eisenberg N. Young children’s coping with interpersonal anger. Child Development. 1992;63:116–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fine SE, Izard CE, Mostow AJ, Trentacosta CJ, Ackerman BP. First grade emotion knowledge as a predictor of fifth grade self-reported internalizing behaviors in children from economically disadvantaged families. Development and Psychopathology. 2003;15:331–342. doi: 10.1017/s095457940300018x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fine SE, Trentacosta CJ, Izard CE, Mostow AJ, Campbell JL. Anger perception, caregivers’ use of physical discipline, and aggression in children at risk. Social Development. 2004;13:213–228. [Google Scholar]

- Garner PW, Jones DC, Miner JL. Social competence among low-income preschoolers: Emotion socialization practices and social cognitive correlates. Child Development. 1994;65:622–637. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garner PW, Lemerise EA. The roles of behavioral adjustment and conceptions of peers and emotions in preschool children’s peer victimization. Development and Psychopathology. 2007;19:57–71. doi: 10.1017/S0954579407070046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garner P, Waajid B. The associations of emotion knowledge and teacher-child relationships to preschool children’s school-related developmental competence. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2008;29:89–100. [Google Scholar]

- Garner PW, Waajid B. Emotion knowledge and self-regulation as predictors of preschoolers’ cognitive ability, classroom behavior, and social competence. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment. 2012;30:330–343. [Google Scholar]

- Halberstadt AG, Denham SA, Dunsmore JC. Affective social competence. Social Development. 2001;10:79–119. [Google Scholar]

- Hayward C, Sanborn K. Puberty and the emergence of gender differences in psychopathology. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2002;30:49–58. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(02)00336-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izard CE. Emotional intelligence or adaptive emotions? Emotion. 2001;1:249–257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izard C, Fine S, Schultz D, Mostow A, Ackerman B, Youngstrom E. Emotion knowledge as a predictor of social behavior and academic competence in children at risk. Psychological Science. 2001;12:18–23. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.00304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izard CE, Haskins FW, Schultz D, Trentacosta CJ, King KA. Emotion Matching Task. Newark, DE: University of Delaware; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Izard CE, Trentacosta CJ, King KA, Mostow AJ. An emotions-based prevention program for Head Start children. Early Education and Development. 2004;15:407–422. [Google Scholar]

- Kaltiala-Heino R, Rimpela M, Rantanen P, Rimpela A. Bullying at school - An indicator of adolescents at risk for mental disorders. Journal of Adolescence. 2000;23:661–674. doi: 10.1006/jado.2000.0351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochenderfer BJ, Ladd GW. Peer victimization: Cause or consequence of school maladjustment? Child Development. 1996;67:1305–1317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusché CA, Greenberg MT. The PATHS curriculum. Seattle, WA: Developmental Research and Programs; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Kusché CA, Greenberg M, Beikle B. The Kusché Affective Interview. Unpublished manuscript, University of Washington, Department of Psychology; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Ladd GW, Birch SH, Buhs ES. Children’s social and scholastic lives in kindergarten: Related spheres of influence? Child Development. 1999;70:1373–1400. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladd GW, Kochenderfer BJ, Coleman CC. Friendship quality as a predictor of young children’s early school adjustment. Child Development. 1996;67:1103–1118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutz MN, Fantuzzo J, McDermott P. Multidimensional assessment of emotional and behavioral adjustment problems of low-income preschool children: Development and initial validation. Early Childhood Research Quarterly. 2002;17:338–355. [Google Scholar]

- Marsh HW, Craven RG, Debus R. Self-concepts of young children 5 to 8 years of age: Measurement and multidimensional structure. Journal of educational Psychology. 1991;83:377–392. [Google Scholar]

- Martin SE, Boekamp JR, McConville DW, Wheeler EE. Anger and sadness perception in clinically referred preschoolers: Emotion processes and externalizing behavior symptoms. Child Psychiatry & Human Development. 2010;41:30–46. doi: 10.1007/s10578-009-0153-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mardell-Czudnowski C, Goldenberg DS. Developmental Indicators for the Assessment of Learning - Third Edition (DIAL-3) Bloomington, MN: Pearson Assessments; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- McCabe PC, Meller PJ. The relationship between language and social competence: How language impairment affects social growth. Psychology in the Schools. 2004;41:313–321. [Google Scholar]

- Miller AL, Fine SE, Gouley KK, Seifer R, Dickstein S. Showing and telling about emotions: Interrelations between facets of emotional competence and associations with classroom adjustment in Head Start preschoolers. Cognition and Emotion. 2006;20:1170–1192. [Google Scholar]

- Miller AL, Gouley KK, Seifer R, Dickstein S, Shields A. Emotions and behaviors in the Head Start classroom: Associations among observed dysregulation, social competence, and preschool adjustment. Early Education and Development. 2004;15:147–165. [Google Scholar]

- Miller AL, Gouley KK, Seifer R, Zakriski A, Eguia M, Vergnani M. Emotion knowledge skills in low-income elementary school children: Associations with social status and peer experiences. Social Development. 2005;14:637–651. [Google Scholar]

- Miller PM, Danaher DL, Forbes D. Sex-related strategies for coping with interpersonal conflict in children aged five and seven. Developmental Psychology. 1986;22:543–548. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan JK, Izard CE, King KA. Construct validity of the emotion matching task: Preliminary evidence for convergent and criterion validity of a new emotion knowledge measure for young children. Social Development. 2010;21:52–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2008.00529.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostrov JM, Keating CF. Sex differences in preschool aggression during free play and structured interactions: An observational study. Social Development. 2004;13:255–277. [Google Scholar]

- Pons F, Harris P, de Rosnay M. Emotion comprehension between 3 and 11 years: Developmental periods and hierarchical organization. European Journal of Developmental Psychology. 2004;1:127–152. [Google Scholar]

- Rieffe C, Rooij M. The longitudinal relationship between emotion awareness and internalising symptoms during late childhood. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2012;21:349–356. doi: 10.1007/s00787-012-0267-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reijntjes A, Kamphuis JH, Prinzie P, Telch MJ. Peer victimization and internalizing problems in children: A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2010;34:244–252. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2009.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rescorla LE. Assessment of young children using the Achenbach system of empirically based assessment (ASEBA) Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews. 2005;11:226–236. doi: 10.1002/mrdd.20071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose AJ, Rudolph KD. A review of sex differences in peer relationship processes: Potential trade-offs for the emotional and behavioral development of girls and boys. Psychological Bulletin. 2006;132:98–131. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.1.98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saft EW, Pianta RC. Teachers’ perceptions of their relationships with students: Effects of child age, gender, and ethnicity of teachers and children. School Psychology Quarterly. 2001;16:125–141. [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer JP. “ Multiple Hypothesis Testing”. Annual Review of Psych. 1995;46:561–584. [Google Scholar]

- Schultz D, Izard CE, Ackerman BP. Children’s anger attribution bias: Relations to family environment and social adjustment. Social Development. 2000;9:284–301. [Google Scholar]

- Schultz D, Izard CE, Ackerman BP, Youngstrom EA. Emotion knowledge in economically disadvantaged children: Self-regulatory antecedents and relations to social difficulties and withdrawal. Development and Psychopathology. 2001;13:53–67. doi: 10.1017/s0954579401001043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shields A, Dickstein S, Seifer R, Giusti L, Dodge Magee K, Spritz B. Emotional competence and early school adjustment: A study of preschoolers at risk. Early Education and Development. 2001;12:73–96. [Google Scholar]

- Sim L, Zeman J. Emotion awareness and identification skills in adolescent girls with bulimia nervosa. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2004;33:760–771. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3304_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Southam-Gerow MA, Kendall PC. A preliminary study of the emotion understanding of youths referred for treatment of anxiety disorders. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 2000;29:319–327. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP2903_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder J, Brooker M, Renee Patrick M, Snyder A, Schrepferman L, Stoolmiller M. Observed peer victimization during early elementary school: Continuity, growth, and relation to risk for child antisocial and depressive behavior. Child Development. 2003;74:1881–1898. doi: 10.1046/j.1467-8624.2003.00644.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterba SK, Prinstein MJ, Cox MJ. Trajectories of internalizing problems across childhood: Heterogeneity, external validity, and sex differences. Developmental Psychopathology. 2007;19:345–366. doi: 10.1017/S0954579407070174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trentacosta CJ, Fine SE. Emotion knowledge, social competence, and behavior problems in childhood and adolescence: A meta-analytic review. Social Development. 2010;19:1–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2009.00543.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trentacosta CJ, Izard CE. Kindergarten children’s emotion competence as a predictor of their academic competence in first grade. Emotion. 2007;7:77–88. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.7.1.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster-Stratton C. The incredible years training series. U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Zeman J, Shipman K, Suveg C. Anger and sadness regulation: Predictions to internalizing and externalizing symptoms in children. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2002;31:393–398. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3103_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]