Abstract

The incidence of human papillomavirus (HPV)-positive oropharyngeal cancers is higher and rising more rapidly among men than women in the United States (U.S.) for unknown reasons. We compared the epidemiology of oral oncogenic HPV infection between men and women aged 14-69 years (N=9,480) within the U.S. National Health and Nutritional Examination Surveys (NHANES) 2009-2012. HPV presence was detected in oral DNA by PCR. Analyses were stratified by gender and utilized NHANES sample weights. Oral oncogenic HPV prevalence was higher among men than women (6.6% vs. 1.5%, p<0.001), corresponding to 7.07 million men vs. 1.54 million women with prevalent infection at any point in time during 2009-2012. Prevalence increased significantly with age, current smoking, and lifetime number of sexual partners for both genders (adjusted p-trends<0.02). However, men had more partners than women (mean=18 vs. 7, p<0.001). Although oncogenic HPV prevalence was similar for men and women with 0-1 lifetime partners, the male-female difference in prevalence significantly increased with number of lifetime partners (adjusted prevalence differences for none, one, 2-to-5, 6-to-10, 11-to-20, and 20+ partners=1.0%, 0.5%, 3.0%, 5.7%, 4.6%, and 9.3%, respectively). Importantly, the per-sexual-partner increase in prevalence was significantly stronger among men than women (adjusted Synergy Index=3.3; 95%CI=1.1-9.7), and this increase plateaued at 25 lifetime partners among men vs.10 partners among women. Our data suggest that the higher burden of oral oncogenic HPV infections and HPV-positive oropharyngeal cancers among men than women arises in part from higher number of lifetime sexual partners and stronger associations with sexual behaviors among men.

Keywords: human papillomavirus, oral, cancer, gender

INTRODUCTION

Oropharyngeal cancers caused by human papillomavirus (HPV) infection are 3 to 5 times more common among men than women (1, 2). Furthermore, in several developed countries worldwide (Australia, Canada, Denmark, Japan, Norway, Sweden, The Netherlands, United Kingdom, and the United States [U.S.]), incidence rates for HPV-positive oropharyngeal cancer have substantially increased among men during the past 3 to 4 decades, while rates have only modestly increased among women (2-6). For example, from 1988 to 2004 in the U.S., the incidence of HPV-positive oropharyngeal cancer increased by 3.2 cases per 100,000 among men (from 1.2 to 4.4 per 100,000) in contrast to an increase of 0.5 cases per 100,000 among women (from 0.4 to 0.9 per 100,000) (2).

In a prior study within the nationally-representative, cross-sectional U.S. National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES) 2009-2010 cycle, we found that the prevalence of oral oncogenic HPV infection was 3-times higher among men than women, consistent with the higher risk for HPV-positive oropharyngeal cancer among men in the U.S. (7). However, the reasons for the male predominance of oral HPV infection are currently unknown (7-10).

Here, we investigated the reasons for higher oral oncogenic HPV infection among men by comparing the distribution as well as the associations of risk factors for oral HPV infection between men and women aged 14-69 years within two consecutive NHANES cycles: 2009-2010 and 2011-2012.

METHODS

Study population

The NHANES 2009-2010 and 2011-2012 included a complex, multistage probability sample of the civilian non-institutionalized U.S. population residing in the 50 states and District of Columbia, with differential sampling rates by race/ethnicity and age (7, 11).

The surveys included interviewer-assisted household interviews, physical examinations, and Computer-Assisted Self-Interviews (CASI) at the mobile examination center (MEC) (11). All MEC participants aged 14-69 years were eligible to participate in the Oral HPV Protocol of NHANES (7, 11). Sociodemographic information was collected through household interviews. Self-reported data on tobacco and alcohol use (ages 20+ years) were collected through Computer Assisted Personal Interviews (CAPI) at the MEC. Self-reported data on tobacco and alcohol use (ages 14-19 years), drug use, and sexual behaviors were collected at the MEC through Audio CASI (ACASI). In both cycles, individuals aged 14-69 years provided data on age at sexual debut, sexual orientation, and number of opposite-sex lifetime sex partners, inclusive of oral (performing or receiving), vaginal, and anal sex partners (performing or receiving). Additionally, individuals aged 14-59 years provided information on number of lifetime and recent (past 12 months) same-sex and opposite-sex partners for oral (performing), vaginal, and anal sex (7, 11).

HPV DNA testing

Participants provided a 30-second oral rinse and gargle of 10 mL ScopeTM mouthwash or saline (7). Samples were stored at 4o C and shipped weekly to the Gillison laboratory at the Ohio State University. DNA was extracted from exfoliated oral cells using the Qiagen Virus/Bacteria Midi kit and subjected to multiplexed polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using PGMY primer pools for HPV and primers for the human β-globin gene. β-globin positive specimens were considered evaluable. The presence of 37 HPV types (18 oncogenic types—16, 18, 26, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 53, 56, 58, 59, 66, 68, 73, and 82— and 19 non-oncogenic types—6, 11, 34, 40, 42, 44, 54, 61, 62, 67, 69, 70, 71, 72, 81, 82 subtype IS39, 83, 84, and 89 [cp6108]) was detected through the Roche Linear Array HPV Genotyping Test (7). We utilized the oncogenic/non-oncogenic classification proposed by Munoz et al. (12) for consistency with prior reports of oral HPV infections in NHANES. We also conducted sensitivity analyses using an updated classification of oncogenic types (12 HPV types classified as Group 1 carcinogens by the International Agency for research on Cancer: 16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, and 59) (13).

Statistical analyses

Of 11,390 MEC participants aged 14-69 years in NHANES 2009-2012 (N=5,987 in NHANES 2009-2010 and N=5,403 in 2011-2012), 891 either did not provide oral rinse specimens (n=889) or provided unevaluable specimens (n=2) and an additional 1,019 participants did not respond to the MEC ACASI questionnaire. Demographic characteristics differed significantly between participants/responders (n=9,480) and nonparticipants/nonresponders (n=1,910) (eTable 1). Therefore, to adjust for bias and to account for the complex survey design, we post-stratified the NCHS sample weights of the responders to match age by race by gender distributions in the U.S. population for each cycle, and utilized these post-stratified weights in all analyses.

All analyses were conducted separately among men and women, unless otherwise specified. The primary outcome of interest was oral oncogenic HPV infection. Individuals infected with non-oncogenic HPV types were included in the reference group to provide unbiased estimates of oncogenic HPV prevalence. To compare and contrast risk factor associations with oral oncogenic HPV between men and women, we utilized prevalence differences (PDs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs), derived from unadjusted and adjusted binary logistic regression models. We utilized PDs because given the significant differences in oral oncogenic HPV prevalence between men and women (7), ratio measures (e.g. prevalence ratios or odds ratios) could mask important male-female differences in risk factor associations. For example, an increase in prevalence from 1% to 2% or 5% to 10% provides the same odds ratio of 2.0, but noticeably different PDs (1% and 5%, respectively). Adjusted PDs consisted of differences between predicted margins (14). Unadjusted and adjusted synergy indices (SIs) and 95% CIs were utilized to statistically compare risk factor associations with oral oncogenic HPV prevalence between men vs. women on an additive scale (15). These synergy indices were calculated in models that included both men and women and incorporated product terms between gender and other risk factors, one interaction per model. We also calculated adjusted male-female prevalence differences from models that included both men and women, with interaction terms for gender with key risk factors.

Statistical significance was assessed through the survey design-adjusted Wald F test. Variables for adjustment in multivariate models were selected a priori as well as based on bivariate analyses. Due to high co-linearity between sexual behaviors, each behavior variable was evaluated in separate models. Non-linear associations of oral oncogenic HPV prevalence with continuous covariates were evaluated using restricted cubic splines with either 5 knots (for age) or 3 knots (for number of lifetime any-, oral-, and vaginal-sex partners) (16).

We estimated the number of U.S. men and women with prevalent oral oncogenic HPV infection (2009-2012) using multivariable models and cross-tabulations. Briefly, using binary logistic regression models, we calculated the predicted probability of prevalent oral oncogenic HPV infection separately among men and women. These predicted probabilities were then summed across subgroups defined by age (categorized as 14-39, 40-59, and 60-69 years to reflect age groups with disparate incidence rates/trends for oropharyngeal cancers) (17), smoking, and number of lifetime sexual partners to calculate the number of infected individuals in the U.S. population. All analyses were conducted using SAS-callable SUDAAN version 11.0.0 (RTI). Two-sided p-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Oral HPV prevalence among men and women

The 9,480 NHANES 2009-2012 MEC participants represented 219,608,892 individuals aged 14-69 years in the U.S. population.

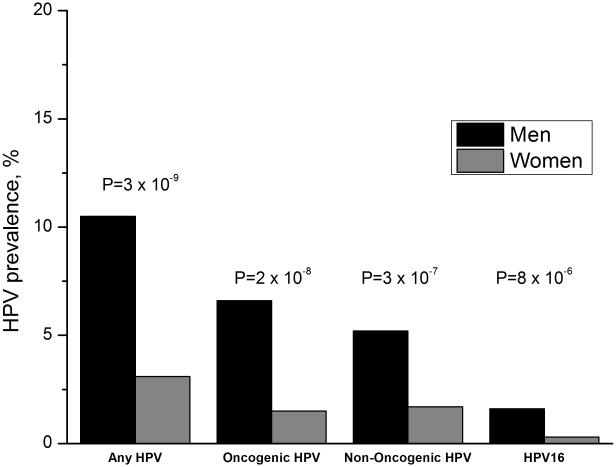

The prevalence of oral HPV infection during 2009-2012 was 6.8% (95%CI=6.0-7.7). Oral HPV prevalence was significantly higher among men than women (10.5% vs. 3.1%, p<0.001), including higher prevalence of oncogenic HPV (6.6% vs. 1.5%, p<0.001), non-oncogenic HPV (5.2% vs. 1.7%, p<0.001), and HPV16 infection (1.6% vs. 0.3%, p<0.001) among men (Figure 1). In both genders, HPV16 was the most prevalent genotype. Prevalence of any, oncogenic, and non-oncogenic oral HPV infection was similar between NHANES 2009-2010 and 2011-2012 (eTable 2).

Figure 1.

Shown is prevalence of any HPV infection, oncogenic HPV infection, non-oncogenic HPV infection, and HPV type 16 infection among men (black bars) and women (grey bars). The p-values comparing HPV prevalence between men and women are also shown.

Behavioral differences between men and women

Men and women differed significantly in several risk behaviors (Table 1). A significantly higher proportion of men than women were heavy cigarette smokers, current marijuana smokers, and heavy alcohol drinkers. Men also reported significantly higher average numbers of lifetime sex partners than women: 18 vs. 7 for any sex, 9 vs. 4 for oral sex, and 16 vs. 7 for vaginal sex (Table 1).

Table 1.

Behavioral differences between men and women in the U.S. population, NHANES 2009-2012

| Characteristic |

Men

Estimate, 95% CI |

Women

Estimate, 95% CI |

Unadjusted

p-value a |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cigarette smoking b | <0.001 | ||

| Never/former | 76.2 (74.2-78.1) | 81.3 (79.6-83.0) | |

| Current, <10 cigarettes/day | 13.4 (11.9-15.0) | 11.5 (10.3-12.8) | |

| Current, 11-20 cigarettes/day | 7.7 (6.5-9.1) | 5.9 (4.7-7.4) | |

| Current, >20 cigarettes/day | 2.7 (1.9-3.7) | 1.2 (0.9-1.5) | |

|

Alcohol use in the past 12 months,

average number of drinks per week c |

<0.001 | ||

| 0 | 21.2 (19.2-23.2) | 34.4 (31.7-37.3) | |

| < 1 | 17.6 (15.8-19.5) | 27.2 (25.0-29.4) | |

| 1-7 | 36.7 (34.4-39.1) | 29.4 (26.6-32.3) | |

| 8-14 | 13.3 (11.7-15.0) | 5.9 (4.6-7.7) | |

| > 14 | 11.0 (10.0-12.2) | 2.6 (2.1-3.3) | |

| Marijuana use d | <0.001 | ||

| Never | 39.8 (37.3-42.4) | 48.9 (45.9-52.0) | |

| Former | 43.1 (40.6-45.6) | 40.7 (37.9-43.5) | |

| Current | 16.4 (14.7-18.3) | 10.0 (8.6-11.7) | |

|

Lifetime number of any sex partners e

Mean (95% CI) |

18.2 (15.2-21.2) | 7.4 (6.5-8.2) | <0.001 |

|

Lifetime number of oral sex partners f

Mean (95% CI) |

9.3 (6.4-12.2) | 4.1 (3.3-5.0) | .001 |

|

Lifetime number of vaginal sex partners f

Mean (95% CI) |

16.4 (13.1-20.0) | 7.1 (6.2-8.0) | <0.001 |

Abbreviations: CI= confidence interval.

Note: percentages shown are column percentages. Numbers do not add to 100% due to missing values.

Adjusted Wald-F p-value.

Analyses based on participants aged 14-69 years. Ever use of cigarettes was defined for individuals age 14-19 as ever having tried cigarettes and for age 20-69 as lifetime use of >100 cigarettes. A current smoker was defined as someone who had smoked a cigarette in the prior 30 days. A former smoker was defined as an ever user who had not smoked a cigarette in the prior 30 days.

Alcohol data were available for individuals aged 20-69 years in NHANES 2009-2010 and for individuals aged 18-69 years in NHANES 2011-2012.

Analyses were restricted to individuals aged 14-59 years. Current marijuana use was defined as use of marijuana at least once within the past 30 days.

Analyses based on participants aged 14-69 years. Lifetime number of any sex partners (vaginal/anal/oral sex combined) included the number of opposite gender partners.

Analyses based on participants aged 14-59 years. Lifetime number of oral or vaginal sex partners included the sum of same and opposite gender partners.

Differences in risk factor associations between men and women

In unadjusted analyses, demographic factors significantly associated with oral oncogenic HPV prevalence among men included older age (with a bimodal pattern), race/ethnicity, high-school or equivalent education, marital status, current smoking (including serum cotinine levels), and marijuana use (eTable 3). Among women, age, race/ethnicity and serum cotinine levels were associated with oral oncogenic HPV prevalence.

In both genders, lifetime and recent any-, oral-, and vaginal-sexual behaviors were strongly associated with oral oncogenic HPV prevalence. Infection was rare among men (0.3%) and women (0.2%) who did not report any sexual activity (homosexual or heterosexual) (eTable 3), and a vast majority of oral oncogenic HPV infections ([7.3%-0.3%]/ 7.3%= 95.9% among men and [1.6%-0.2%]/ 1.6%= 87.5% among women) were attributable to sexual behavior.

Notably, significant additive interactions were observed with gender for several factors (eTable 3). Associations were significantly stronger among men than women for older age (SI=4.8), current cigarette smoking (SI=2.0), and marijuana use (SI=2.9). Likewise, for all lifetime and recent sexual behaviors, the associations were 1.7 to 4.8 times stronger among men than women. For example, oncogenic HPV prevalence was 13.8% higher among men with over 20 lifetime any sex partners as compared to none, but only 3.4% higher among women (SI=3.9; 95%CI=2.1-7.3) (eTable 3).

Differences in the distribution of demographic and behavioral risk factors explained only ~18% of the male-female differences in oral oncogenic HPV prevalence (unadjusted male-female PD of 5.1% vs. adjusted PD of 4.2%, after adjustment for age, race, education, marital status, smoking, and lifetime number of any sexual partners).

In multivariable analyses stratified by gender, age, current cigarette smoking, and number of lifetime sexual partners were independently associated with oral oncogenic HPV prevalence among both men and women (Table 2). However, the associations for these factors were significantly stronger among men than women (Table 2 and eFigure 1). Prevalence of oral oncogenic HPV increased with increasing age in a bimodal pattern among both men and women, with peaks at ages 25-30 and 55-60 years among men and ages 20-24 and 55-60 years among women (eFigure 1). However, the increase in oral HPV prevalence with age appeared stronger among men than women (eFigure 1). Likewise, current smoking, particularly at 1-10 cigarettes per day, had a stronger association with increased oncogenic HPV prevalence among men than women (SI=1.6; 95%CI=1.0 to 2.6; Table 2).

Table 2.

Adjusted associations of demographic and behavioral factors with oral oncogenic HPV prevalence among men and women in the U.S. population, NHANES 2009-2012

| Men | Women | Men vs. Women |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | # subjects (#infected) |

Unadjusted Prevalence (95% CI) |

Adjusted Prevalence difference (95%CI) |

# subjects (#infected) |

Unadjusted Prevalence (95% CI) |

Adjusted Prevalence difference (95%CI) |

Adjusted synergy index (95%CI) a |

| Race/Ethnicity b | 0.7 (0.5 to 0.9) |

||||||

| Mexican American | 849 (33) | 3.9 (2.9 to 5.2) | −1.6 (−3.8 to 0.6) | 738 (11) | 1.4 (0.8 to 2.4) | 0.7 (−0.8 to 2.2) | |

| Other Hispanic | 492 (29) | 5.9 (3.4 to 10.2) | −0.9 (−4.4 to 2.6) | 535 (14) | 3.0 (1.8 to 5.1) | 2.4 (0.5 to 4.3) | |

| White, Non-Hispanic | 1826 (131) | 7.1 (5.7 to 8.7) | Ref | 1756 (33) | 1.4 (0.8 to 2.3) | Ref | |

| Black, Non-Hispanic | 1148 (91) | 8.1 (6.7 to 9.8) | −0.8 (−2.2 to 0.6) | 1112 (16) | 1.6 (0.9 to 2.7) | 0.2 (−0.9 to 1.3) | |

| Other race | 538 (18) | 4.4 (2.4 to 8.0) | −1.2 (−4.5 to 2.0) | 486 (5) | 0.7 (0.3 to 1.7) | −0.3 (−1.5 to 0.9) | |

| p-value | 0.51 | 0.03 | |||||

| Education b | NE | ||||||

| Less than high-school | 1681 (74) | 3.9 (2.7 to 5.5) | Ref | 1449 (24) | 1.7 (0.9 to 3.2) | Ref | |

| High-school or equivalent | 1022 (75) | 8.1 (5.8 to 11.1) | 2.0 (−0.7 to 4.7) | 847 (21) | 2.0 (1.0 to 3.7) | −0.1 (−1.6 to 1.4) | |

| Some college or greater | 2146 (153) | 7.2 (5.7 to 9.2) | 2.3 (−0.2 to 4.8) | 2327 (34) | 1.2 (0.8 to 2.0) | −0.9 (−2.3 to 0.5) | |

| p-value | 0.25 | 0.29 | |||||

| Marital Status b | 0.7 (0.3 to 1.5) |

||||||

| Never married | 1853 (77) | 5.6 (3.7 to 8.6) | Ref | 1651 (29) | 1.6 (0.9 to 2.9) | Ref | |

| Married/living with partner | 2430 (164) | 6.7 (5.2 to 8.6) | −2.6 (−7.0 to 1.8) | 2128 (32) | 1.1 (0.7 to 1.6) | −0.7 (−1.7 to 0.4) | |

| Widowed/divorced/separated | 567 (61) | 9.2 (6.7 to 12.5) | −2.6 (−6.3 to 1.2) | 845 (18) | 2.4 (1.3 to 4.3) | −0.2 (−1.3 to 1.0) | |

| p-value | 0.35 | 0.40 | |||||

| Cigarette Use b | 1.6 (1.0 to 2.6) |

||||||

| Never/former | 3604 (169) | 5.2 (4.1 to 6.5) | Ref | 3774 (51) | 1.2 (0.8 to 1.8) | Ref | |

| Current, <10 cigarettes/day | 773 (78) | 12.3 (8.8 to 16.8) | 6.2 (2.4 to 10.0) | 555 (13) | 1.9 (1.0 to 3.3) | 0.1 (−0.7 to 1.0) | |

| Current, 11-20 cigarettes/day | 353 (39) | 8.6 (5.0 to 14.4) | 1.0 (−2.9 to 5.0) | 241 (10) | 3.1 (1.4 to 6.8) | 1.1 (−0.4 to 2.6) | |

| Current, >20 cigarettes/day | 110 (15) | 13.9 (7.5 to 24.4) | 5.2 (−0.4 to 10.7) | 49 (5) | 9.0 (2.9 to 24.8) | 5.7 (−1.2 to 12.6) | |

| p-value (p-trend) | <0.001 (<0.001) | 0.03 (0.02) | |||||

|

Number of lifetime sex

partners (any sex) b |

3.3 (1.1 to 9.5) |

||||||

| 0 | 685 (6) | 0.9 (0.3 to 2.5) | Ref | 596 (3) | 0.2 (0.1 to 0.7) | Ref | |

| 1 | 489 (8) | 1.1 (0.5 to 2.7) | −0.3 (−2.2 to 1.6) | 805 (7) | 0.6 (0.3 to 1.2) | 0.4 (−0.2 to 1.0) | |

| 2-5 | 1100 (49) | 4.1 (2.8 to 5.9) | 2.6 (0.4 to 4.8) | 1706 (29) | 1.1 (0.6 to 2.2) | 0.8 (−0.01 to 1.6) | |

| 6-10 | 913 (70) | 7.7 (5.1 to 11.4) | 5.9 (2.6 to 9.1) | 855 (19) | 1.7 (1.0 to 3.0) | 1.6 (0.6 to 2.5) | |

| 11-20 | 731 (51) | 8.0 (5.7 to 11.2) | 5.8 (2.8 to 8.8) | 364 (12) | 2.7 (1.3 to 5.8) | 2.3 (0.2 to 4.4) | |

| >21 | 853 (110) | 14.7 (11.6 to 18.5) | 11.0 (7.8 to 14.1) | 234 (8) | 3.6 (1.5 to 8.6) | 3.1 (0.4 to 5.7) | |

| p-value (p-trend) | <0.001 (<0.001) | 0.01 (0.003) | |||||

| Number of lifetime oral sex partners c | 2.8 (1.2 to 6.3) |

||||||

| 0 | 1154 (16) | 1.6 (0.8 to 3.3) | Ref | 1168 (11) | 0.6 (0.3 to 1.3) | Ref | |

| 1 | 653 (20) | 2.1 (1.1 to 3.9) | −0.01 (−2.3 to 2.2) | 788 (9) | 1.2 (0.5 to 2.8) | 0.7 (−0.6 to 1.9) | |

| 2-5 | 1311 (79) | 5.6 (4.2 to 7.4) | 2.9 (1.2 to 4.6) | 1420 (26) | 1.1 (0.6 to 1.9) | 0.5 (−0.2 to 1.2) | |

| 6-10 | 430 (37) | 8.4 (5.8 to 12.0) | 5.2 (2.4 to 8.0) | 295 (12) | 3.1 (1.6 to 6.0) | 2.4 (0.1 to 4.6) | |

| 11-20 | 290 (36) | 15.1 (9.1 to 24.0) | 10.9 (4.4 to 17.5) | 104 (4) | 3.9 (0.9 to 15.8) | 2.6 (−0.8 to 6.1) | |

| >21 | 215 (39) | 17.2 (12.6 to 23.0) | 12.3 (6.4 to 18.2) | 86 (5) | 5.0 (1.5 to 15.9) | 3.6 (−2.3 to 9.5) | |

| p-value (p-trend) | <0.001 (<0.001) | 0.02 (0.009) | |||||

|

Number of lifetime vaginal

sex partners d |

3.6 (1.8 to 7.2) |

||||||

| 0 | 712 (7) | 0.6 (0.3 to 1.3) | Ref | 605 (3) | 0.2 (0.1 to 0.7) | Ref | |

| 1 | 492 (15) | 2.2 (1.0 to 4.7) | 1.3 (−0.9 to 3.4) | 732 (9) | 0.8 (0.4 to 1.5) | 0.7 (0.04 to 1.4) | |

| 2-5 | 980 (40) | 4.0 (2.5 to 6.3) | 2.8 (1.0 to 4.7) | 1324 (24) | 1.3 (0.7 to 2.6) | 1.0 (0.02 to 2.0) | |

| 6-10 | 704 (49) | 7.6 (5.1 to 11.2) | 6.0 (3.2 to 8.7) | 713 (17) | 1.7 (0.9 to 3.1) | 1.4 (0.4 to 2.5) | |

| 11-20 | 562 (41) | 8.8 (6.1 to 12.5) | 6.5 (3.8 to 9.3) | 299 (8) | 2.2 (0.9 to 5.3) | 1.6 (−0.1 to 3.3) | |

| >21 | 600 (75) | 13.9 (10.4 to 18.3) | 10.2 (7.0 to 13.4) | 184 (6) | 3.7 (1.3 to 10.1) | 2.8 (−0.1 to 5.6) | |

| p-value (p-trend) | <0.001 (<0.001) | 0.04 (0.03) | |||||

|

Alcohol use in the past 12

months, average number of drinks per week e |

0.9 (0.4 to 2.0) |

||||||

| 0 | 1041 (74) | 7.3 (4.9 to 10.6) | Ref | 1700 (28) | 1.8 (1.0 to 3.3) | Ref | |

| <1 | 765 (48) | 6.5 (4.0 to 10.4) | −1.2 (−6.1 to 3.8) | 1029 (24) | 2.0 (1.1 to 3.4) | 0.2 (−1.0 to 1.4) | |

| 1-7 | 1348 (99) | 6.9 (4.7 to 9.8) | −1.4 (−5.3 to 2.6) | 950 (17) | 1.0 (0.7 to 1.6) | −0.7 (−2.0 to 0.5) | |

| 8-14 | 486 (38) | 8.4 (6.0 to 11.7) | −1.4 (−5.6 to 2.8) | 173 (3) | 0.9 (0.3 to 2.9) | −1.1 (−2.1 to −0.02) | |

| > 14 | 424 (36) | 8.7 (5.9 to 12.7) | −2.5 (−5.6 to 0.7) | 94 (2) | 1.0 (0.8 to 1.3) | −1.3 (−2.5 to −0.1) | |

| p-value (p-trend) | 0.70 (0.16) | 0.23 (0.03) | |||||

| Marijuana use f | 2.2 (1.0 to 4.7) |

||||||

| Never | 1877 (60) | 2.9 (2.1 to 3.8) | Ref | 2214 (27) | 1.0 (0.7 to 1.6) | Ref | |

| Former | 1496 (116) | 8.5 (6.9 to 10.5) | 2.1 (0.2 to 4.0) | 1278 (27) | 1.7 (1.0 to 3.0) | −0.1 (−1.0 to 0.9) | |

| Current | 681 (51) | 8.0 (5.5 to 11.6) | 0.4 (−2.1 to 2.9) | 385 (14) | 2.9 (1.6 to 5.3) | 0.6 (−0.7 to 1.9) | |

| p-value (p-trend) | 0.07 (0.76) | 0.30 (0.43) | |||||

Abbreviation: CI= confidence interval; NE= Not estimable.

The synergy index compares the association of factors with oral oncogenic HPV prevalence between men and women on an additive scale. For each factor, the synergy index compares the association of all levels combined vs. the reference group between men vs. women. Confidence limits that do not overlap 1.0 denotes a statistically significant synergy index at p<0.05. A synergy index above 1.0 indicates that the association of the factor is stronger among men than women, while a synergy index less than 1.0 indicates that the association of the factor is stronger among women than men.

Analyses included individuals aged 14-69 years. Models were adjusted for age (modeled as a 5-knot restricted cubic splines), race, education, marital status, cigarette smoking, and number of lifetime any sex partners. See eFigure 1 for associations of age with oncogenic HPV prevalence among men and women.

Data on number of lifetime oral sex partners were available for individuals aged 14-59 years. Models were adjusted for age (modeled with restricted cubic splines), race, education, marital status, cigarette smoking, and number of lifetime oral sex partners.

Data on number of lifetime vaginal sex partners were available for individuals aged 14-59 years. Models were adjusted for age (modeled with restricted cubic splines), race, education, marital status, cigarette smoking, and number of lifetime vaginal sex partners.

Alcohol data were available for individuals aged 20-69 years in NHANES 2009-2010 and for individuals aged 18-69 years in NHANES 2011-2012. Models were adjusted for age (modeled with restricted cubic splines), race, education, marital status, cigarette smoking, alcohol use, and number of lifetime any sex partners.

Marijuana data were available for individuals aged 14-59 years. Models were adjusted for age (modeled with restricted cubic splines), race, education, marital status, cigarette smoking, marijuana use, and number of lifetime any sex partners.

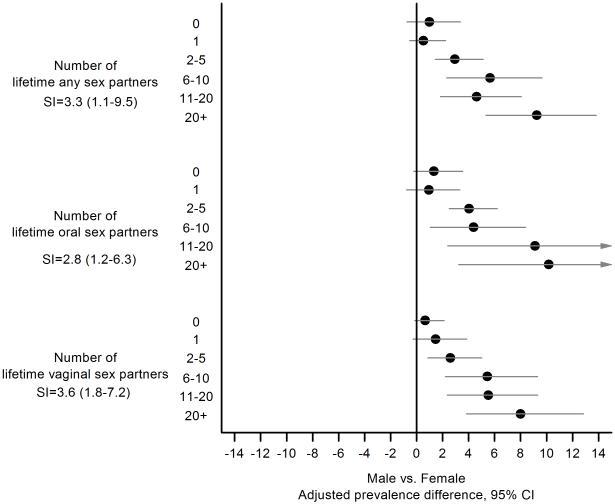

Importantly, we observed significant effect modification between gender and sexual behaviors. For all lifetime sexual behaviors (number of any-, oral-, and vaginal-sexual partners), oral oncogenic HPV prevalence was similar between men and women with none or one lifetime partners, but the male-female prevalence difference significantly increased with increasing number of partners (Figure 2). For example, the male-female prevalence difference was close to zero (PD=0.5%; 95% CI=-0.5% to 1.6%) for individuals with one lifetime any sex partner versus 9.3% (95%CI=5.4% to 13.2%) for individuals with 20+ lifetime any sex partners.

Figure 2.

Shown are male-female prevalence differences for oral oncogenic HPV infection (circles) and 95% confidence intervals (horizontal lines) stratified by lifetime number of any, oral, and vaginal sex partners. Male-female prevalence differences were calculated in separate models for each sexual behavior, and included age (modeled as splines with 5 knots), gender, race, marital status, education, cigarette smoking, lifetime number of partners, and interaction between gender and lifetime number of partners. Data on lifetime number of any sex partners were available for individuals aged 14-69 years, while data on number of lifetime oral or vaginal sex partners were available for individuals aged 14-59 years.

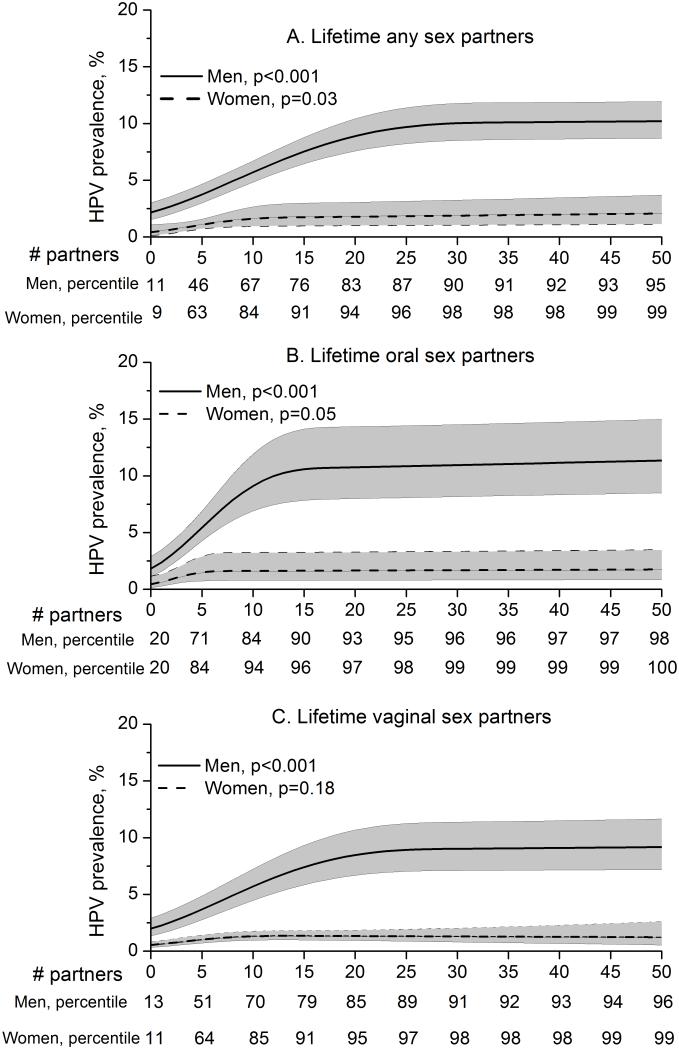

The increase in oral oncogenic HPV prevalence with lifetime sexual behaviors was consistently 3-4 times greater among men than women (Table 2 and Figure 2, SI for lifetime any sex partners=3.3, oral sex partners=2.8, vaginal sex partners=3.6). To further investigate differences in sexual behavior associations between men and women, we conducted multivariable analyses using lifetime sexual behaviors in a flexible form with restricted cubic splines (Figure 3). These analyses showed two important differences in sexual behavioral associations between men and women. First, the per-partner (lifetime any-, oral-, or vaginal-sex) increase in oral oncogenic HPV prevalence was higher among men than women. Second, the increase in oral oncogenic HPV prevalence appeared to plateau at a higher number of lifetime sex partners among men than among women (25 vs. 10 any sex partners, 15 vs. 5 oral sex partners, and 20 vs. 5 vaginal sex partners).

Figure 3.

Shown is the modeled oral oncogenic human papillomavirus (HPV) prevalence and 95% confidence intervals (shaded area) among men (solid line) and women (broken line) by individual number of lifetime any sex partners (panel A), number of lifetime oral sex partners (panel B), and number of lifetime vaginal sex partners (panel C). All sexual behaviors were modeled with restricted cubic splines with 3 knots. Models were stratified by gender and incorporated adjustment for age (as splines with 5 knots), race, marital status, education, and cigarette smoking. The presentation of plots was truncated at 50 lifetime sex partners for visual comparison between men and women. The p-values for the association of each sexual behavior (one linear term + one spline term) with oncogenic HPV prevalence are also shown in each panel. The population percentiles for the number of sex partners for men and women are shown below the x-axis in each panel. Given the standardization for covariates included in the multivariate model, the oncogenic HPV prevalence curve obtained from the adjusted model is presented at the mean levels of the covariates (age, race, education, marital status, and smoking, as appropriate)

Differences in burden of oral oncogenic HPV infection between men and women

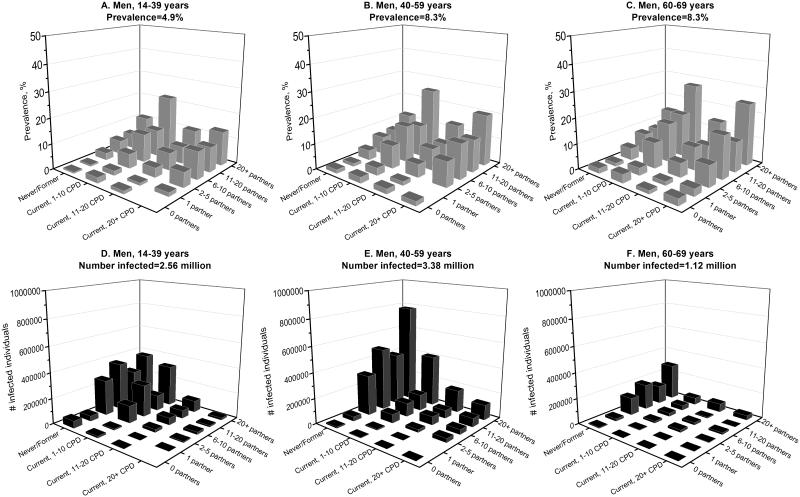

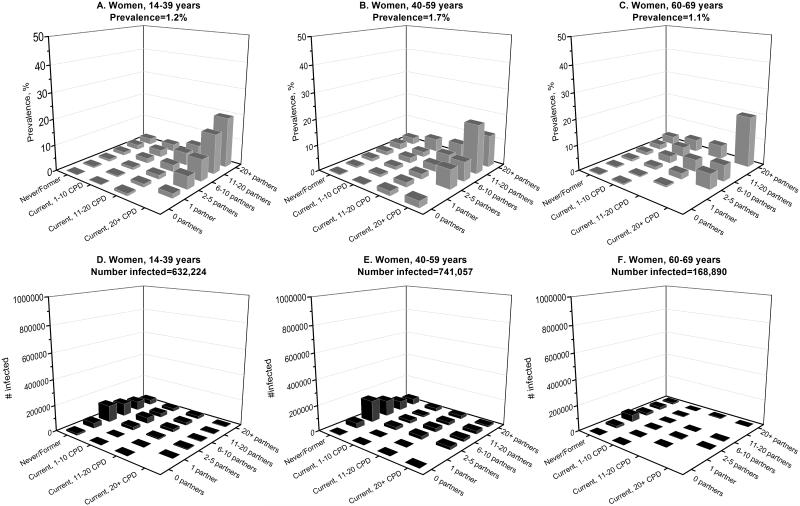

To further contrast the epidemiology of oral oncogenic HPV infections in men and women in the U.S. population, we estimated infection prevalence separately among men and women across subgroups defined by the key risk factors—age, cigarette smoking, and lifetime number of sexual partners (Figure 4, A-C and Figure 5 A-C). Oral oncogenic HPV prevalence was higher among men than women across all population subgroups. Prevalence was highest among men aged 60-69 years who currently smoked 1-10 cigarettes per day and reported more than 20 lifetime sexual partners (27.3%, Figure 4C). Among women, prevalence was highest among those aged 60-69 years who currently smoked more than 20 cigarettes per day and reported more than 20 lifetime sexual partners (19.7%, Figure 5C).

Figure 4.

Shown is the burden of oral oncogenic HPV infection among men in the U.S. population, as measured by oncogenic HPV prevalence (panels A, B, and C) and the number of infected individuals (panels D, E, and F). Estimates for prevalence and number of infected individuals for men are stratified by age (14-40, 40-59, and 60-69 years), cigarette smoking status (never/former smokers, current smokers who smoked 1-10 cigarettes per day, current smokers who smoked 11-20 cigarettes per day, and current smokers who smoked 20+ cigarettes per day), and lifetime number of any sex partners (0, 1, 2-5, 6-10, 11-20, and 20+ partners). The predicted probability of infection with oral oncogenic HPV infection was estimated from multivariable models that were adjusted for age (modeled as splines with 5 knots), race, marital status, education, smoking, and number of lifetime any sex partners. These predicted probabilities were then summed across subgroups defined by age, smoking, and number of lifetime sex partners to calculate the number of infected individuals in the U.S. population. Prevalence was calculated as the ratio of number of infected individuals over the total number of individuals within a subgroup.

Figure 5.

Shown is the burden of oral oncogenic HPV infection among women in the U.S. population, as measured by oncogenic HPV prevalence (panels A, B, and C) and the number of infected individuals (panels D, E, and F). Estimates for prevalence and number of infected individuals for women are stratified by age (14-40, 40-59, and 60-69 years), cigarette smoking status (never/former smokers, current smokers who smoked 1-10 cigarettes per day, current smokers who smoked 11-20 cigarettes per day, and current smokers who smoked 20+ cigarettes per day), and lifetime number of any sex partners (0, 1, 2-5, 6-10, 11-20, and 20+ partners). The predicted probability of infection with oral oncogenic HPV infection was estimated from multivariable models that were adjusted for age (modeled as splines with 5 knots), race, marital status, education, smoking, and number of lifetime any sex partners. These predicted probabilities were then summed across subgroups defined by age, smoking, and number of lifetime sex partners to calculate the number of infected individuals in the U.S. population. Prevalence was calculated as the ratio of number of infected individuals over the total number of individuals within a subgroup.

We then contrasted prevalence with the absolute number of individuals with an oral oncogenic HPV infection (Figure 4 D-F and Figure 5 D-F). Because the number of U.S. men and women in the high prevalence subgroups noted above was relatively small (202,397 men and 10,660 women), the majority of individuals with an oral oncogenic HPV infection were in subgroups with relatively low prevalence— men and women aged 40-59 years who were never/former smokers (Figures 4E and 5E). Overall, the number of individuals in the U.S. population with a prevalent oral oncogenic HPV infection was substantially higher among men vs. women (7.07 million men vs. 1.54 million women).

Results were very similar in sensitivity analyses using an updated classification of 12 HPV types as oncogenic types (eFigure 2, eTable 4, eFigure 5).

DISCUSSION

The burden of oral oncogenic HPV infection was substantially greater among men than women (prevalence of 6.6% vs. 1.5%; 7.07 million vs. 1.54 million with prevalent infection; and 1.76 million vs. 0.37 million with oral HPV16 infection) in the U.S. during 2009-2012. Our data indicate that this greater burden of oral oncogenic HPV infection among men arises from a higher number of lifetime sexual partners, and more importantly, stronger associations between sexual behavior and infection among men as compared to women. We also show that the distribution of oral oncogenic HPV infections in the U.S. population parallels the population-level incidence of HPV-positive oropharyngeal cancer, with both infection and cancer being most common among men aged 40-59 years who are never or former smokers (2, 3, 18).

The majority of oral oncogenic HPV infections among both men and women are attributable to sexual behavior. Yet, men had substantially higher prevalence than women. This higher prevalence among men is partly explained by the significantly higher number of lifetime sexual partners reported by men than women. However, only 18% of the male-female difference in prevalence was explained by differences in risk behaviors (i.e. confounding by smoking and number of sexual partners) between men and women, consistent with prior reports from NHANES 2009-2010 (9, 19). A novel observation in our study is the more important role of effect modification between sexual behaviors and gender, with substantially stronger associations between sexual behaviors and oral HPV infection among men than women. Indeed, oncogenic HPV prevalence was similar between men and women with none or one lifetime partners, but this male-female difference significantly increased with increasing number of partners. For all lifetime sexual behavioral metrics (any, oral, or vaginal sex partners), the per-partner increase in oral oncogenic HPV prevalence was 3 to 4-times stronger among men when compared with women.

The stronger per-partner increase in oral HPV prevalence among men than women is consistent with a hypothesis of higher risk of transmission via oral sex performed on a woman than on a man. Risk of oral HPV infection is reportedly higher among heterosexual than homosexual men (20). Furthermore, studies of heterosexual couples have shown higher rates of genital HPV transmission from women to men than vice versa (21, 22).

Differences in immune responses between genders may also contribute to the increased susceptibility of men to oral HPV infection. Men are generally more susceptible than women to parasitic, bacterial, and viral infections due to weaker immune responses to both natural infection and vaccination (23). Several observations from studies of anogenital HPV infections support weaker immune responses to HPV infection among men when compared to women (10). These observations include: lower rates of seroconversion following genital HPV infection among men (24, 25); despite similar genital HPV prevalence (at younger ages) in both genders (26, 27); lower antibody titers upon seroconversion among men than women (24); the absence of acquired immunity against re-infection among men (28-30); the absence of age-related declines in genital HPV prevalence among men (26); and higher genital and oral HPV viral loads among men than women (31, 32). The weaker immune response to HPV among men could potentially explain our observations of the later plateau in prevalence with increasing number of sexual partners and the stronger increase in oral HPV prevalence with increasing age among men versus women.

Our data show strong parallels between the distribution of oral oncogenic HPV infections and HPV-positive oropharyngeal cancers in the U.S. population (2, 3). For example, the 5-times higher incidence of HPV-positive oropharyngeal cancers among men is consistent with the approximately 5-times higher prevalence of oral oncogenic infection as well as of HPV16 infection among men than women (2, 7). Likewise, the number of individuals with oral oncogenic HPV infections was highest among men aged 40-59 years (3.4 million). The reported predominance of HPV-positive oropharyngeal cancers among never/former smokers is also consistent with the high number of infected individuals in this subgroup (3, 18). Our observation that never/former smokers constitute the overwhelming majority of individuals with prevalent oral oncogenic HPV infection could potentially explain the paradoxical association of smoking with oral HPV prevalence but not with risk of HPV-positive oropharyngeal cancers (33).

Although our study was conducted in a representative sample of the U.S. population, our results have global relevance. Similar to observations in the U.S., the incidence of oropharyngeal cancer has rapidly increased over the past 3-4 decades in several developed countries around the world, including Australia, Canada, Denmark, Japan, Norway, Sweden, The Netherlands, and United Kingdom (2-6). This increase, which has been attributed to HPV infection (2), has occurred predominantly among men younger than 60 years (3, 6). Our data provide a potential explanation for this steeper increase in incidence among young men. Compared to women, men had a stronger per-sexual partner increase in oral HPV prevalence, later plateau in prevalence with increasing number of sexual partners, and a stronger increase in prevalence with increasing age. These observations underscore a disproportionately greater impact of sexual behavioral changes over the last several decades on increased oral HPV exposure among recent birth cohorts of men than women (6, 17). Thus, both behavioral and biologic differences between men and women likely contributed to differential birth cohort effects of the “sexual revolution,” resulting in a dominant bimodal age pattern and consequent rise in oropharyngeal cancer incidence, predominantly among young men.

We note the limitations of our study. Although the use of ACASI enhances the validity of self-reported sexual behavioral data (34). we acknowledge that men over-report and women under-report lifetime sexual partnerships (35). Such a bias may differentially attenuate associations between sexual behaviors and oral HPV among men and women. The presence of statistical interactions between gender and sexual behaviors precluded a quantitative evaluation of the degree to which differences in sexual behaviors accounted for the male-female difference in oral HPV prevalence. Instead, we present male-female prevalence differences stratified by number of sexual partners to show that men and women had similar oral HPV prevalence at low numbers of sexual partners. Given the cross-sectional nature of NHANES, we cannot address the relative contribution of incidence versus persistence to the observed prevalence differences by gender.

Our observations have potential public health implications. Prophylactic HPV vaccines may protect against oral HPV infections (36). Our observation of a substantially higher burden of oral HPV infection among men, coupled with the reported rapid rise in HPV-positive oropharyngeal cancers among men in several developed countries worldwide (2, 6), underscores the importance of recent efforts to enhance the uptake of prophylactic HPV vaccines among men (37-40).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: Merck, NIDCR, NCI Intramural Program, Ohio State University, and Oral Cancer Foundation.

Role of funding sources

The study was funded in part by Merck Inc, the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, the Intramural Program of the National Cancer Institute, the Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center, and the Oral Cancer Foundation. Industry sponsors had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Précis: Epidemiological results argue that the incidence of HPV-positive oropharyngeal cancer is higher and rising more sharply among men than women in the U.S. because of gender-associated sexual behaviors.

Conflicts of interest

Anil Chaturvedi, Barry Graubard, Tatevik Broutian, Robert Pickard, Zhen-yue Tong, Weihong Xiao, and Lisa Kahle do not have any conflicts of interest to disclose. Maura Gillison has consulted for Glaxo Smith Klein and has received research funding from Merck Inc.

Contributor Information

Anil K. Chaturvedi, Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, 9609 Medical Center Drive, 6E-238, Rockville, MD 20850, USA

Barry I. Graubard, Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, 9609 Medical Center Drive, 7E-140, Rockville, MD 20850, USA

Tatevik Broutian, The Ohio State University, 420 West 12th Avenue, Room 620, Columbus, OH 43210, USA.

Robert K.L. Pickard, The Ohio State University, 420 West 12th Avenue, Room 620, Columbus, OH 43210, USA

Zhen-yue Tong, The Ohio State University, 420 West 12th Avenue, Room 620, Columbus, OH 43210, USA.

Weihong Xiao, The Ohio State University, 420 West 12th Avenue, Room 620, Columbus, OH 43210, USA.

Lisa Kahle, Information Management Services, Calverton, MD 20705.

Maura L. Gillison, The Ohio State University, 420 West 12th Avenue, Room 620, Columbus, OH 43210, USA

Reference List

- (1).D'Souza G, Kreimer AR, Viscidi R, Pawlita M, Fakhry C, Koch WM, et al. Case-control study of human papillomavirus and oropharyngeal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1944–56. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa065497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Chaturvedi AK, Engels EA, Pfeiffer RM, Hernandez BY, Xiao W, Kim E, et al. Human papillomavirus and rising oropharyngeal cancer incidence in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:4294–301. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.4596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Marur S, D'Souza G, Westra WH, Forastiere AA. HPV-associated head and neck cancer: a virus-related cancer epidemic. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:781–9. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70017-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Hong AM, Grulich AE, Jones D, Lee CS, Garland SM, Dobbins TA, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma of the oropharynx in Australian males induced by human papillomavirus vaccine targets. Vaccine. 2010;28:3269–72. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.02.098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Ramqvist T, Dalianis T. Oropharyngeal cancer epidemic and human papillomavirus. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010;16:1671–7. doi: 10.3201/eid1611.100452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Chaturvedi AK, Anderson WF, Lortet-Tieulent J, Curado MP, Ferlay J, Franceschi S, et al. Worldwide trends in incidence rates for oral cavity and oropharyngeal cancers. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:4550–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.50.3870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Gillison ML, Broutian T, Pickard RK, Tong ZY, Xiao W, Kahle L, et al. Prevalence of oral HPV infection in the United States, 2009-2010. JAMA. 2012;307:693–703. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Sanders AE, Slade GD, Patton LL. National prevalence of oral HPV infection and related risk factors in the U.S. adult population. Oral Dis. 2012;18:430–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2011.01892.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).D'Souza G, Cullen K, Bowie J, Thorpe R, Fakhry C. Differences in oral sexual behaviors by gender, age, and race explain observed differences in prevalence of oral human papillomavirus infection. PLoS One. 2014;9:e86023. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0086023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Giuliano AR, Nyitray AG, Kreimer AR, Pierce Campbell CM, Goodman MT, Sudenga SL, et al. EUROGIN 2014 roadmap: Differences in human papillomavirus infection natural history, transmission and human papillomavirus-related cancer incidence by gender and anatomic site of infection. Int J Cancer. 2014 doi: 10.1002/ijc.29082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. U S Department of Health and Human Services; Hyattsville, MD: 2014. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Data. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- (12).Munoz N, Bosch FX, de SS, Herrero R, Castellsague X, Shah KV, et al. Epidemiologic classification of human papillomavirus types associated with cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:518–27. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Bouvard V, Baan R, Straif K, Grosse Y, Secretan B, El GF, et al. A review of human carcinogens--Part B: biological agents. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:321–2. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(09)70096-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Korn EL, Graubard BI. Analysis of Health Surveys. Wiley Series in Probability and Statistics. 1999 [Google Scholar]

- (15).Assmann SF, Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S, Mundt KA. Confidence intervals for measures of interaction. Epidemiology. 1996;7:286–90. doi: 10.1097/00001648-199605000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Durrleman S, Simon R. Flexible regression models with cubic splines. Stat Med. 1989;8:551–61. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780080504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Chaturvedi AK, Engels EA, Anderson WF, Gillison ML. Incidence trends for human papillomavirus-related and -unrelated oral squamous cell carcinomas in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:612–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.1713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Applebaum KM, Furniss CS, Zeka A, Posner MR, Smith JF, Bryan J, et al. Lack of association of alcohol and tobacco with HPV16-associated head and neck cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99:1801–10. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djm233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Gillison ML, Broutian T, Pickard RK, Tong ZY, Xiao W, Kahle L, et al. Prevalence of oral HPV infection in the United States, 2009-2010. JAMA. 2012;307:693–703. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Beachler DC, D'Souza G, Sugar EA, Xiao W, Gillison ML. Natural history of anal vs oral HPV infection in HIV-infected men and women. J Infect Dis. 2013;208:330–9. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Hernandez BY, Wilkens LR, Zhu X, Thompson P, McDuffie K, Shvetsov YB, et al. Transmission of human papillomavirus in heterosexual couples. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14:888–94. doi: 10.3201/eid1406.070616.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Nyitray AG, Lin HY, Fulp WJ, Chang M, Menezes L, Lu B, et al. The role of monogamy and duration of heterosexual relationships in human papillomavirus transmission. J Infect Dis. 2014;209:1007–15. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Klein SL. The effects of hormones on sex differences in infection: from genes to behavior. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2000;24:627–38. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(00)00027-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Markowitz LE, Sternberg M, Dunne EF, McQuillan G, Unger ER. Seroprevalence of human papillomavirus types 6, 11, 16, and 18 in the United States: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2003-2004. J Infect Dis. 2009;200:1059–67. doi: 10.1086/604729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Edelstein ZR, Carter JJ, Garg R, Winer RL, Feng Q, Galloway DA, et al. Serum antibody response following genital {alpha}9 human papillomavirus infection in young men. J Infect Dis. 2011;204:209–16. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Giuliano AR, Lee JH, Fulp W, Villa LL, Lazcano E, Papenfuss MR, et al. Incidence and clearance of genital human papillomavirus infection in men (HIM): a cohort study. Lancet. 2011;377:932–40. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62342-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Hariri S, Unger ER, Sternberg M, Dunne EF, Swan D, Patel S, et al. Prevalence of genital human papillomavirus among females in the United States, the National Health And Nutrition Examination Survey, 2003-2006. J Infect Dis. 2011;204:566–73. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Lu B, Viscidi RP, Wu Y, Lee JH, Nyitray AG, Villa LL, et al. Prevalent serum antibody is not a marker of immune protection against acquisition of oncogenic HPV16 in men. Cancer Res. 2012;72:676–85. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-0751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Safaeian M, Porras C, Schiffman M, Rodriguez AC, Wacholder S, Gonzalez P, et al. Epidemiological study of anti-HPV16/18 seropositivity and subsequent risk of HPV16 and -18 infections. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102:1653–62. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Wilson L, Pawlita M, Castle PE, Waterboer T, Sahasrabuddhe V, Gravitt PE, et al. Seroprevalence of 8 Oncogenic Human Papillomavirus Genotypes and Acquired Immunity Against Reinfection. J Infect Dis. 2014 doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Bleeker MC, Hogewoning CJ, Berkhof J, Voorhorst FJ, Hesselink AT, van Diemen PM, et al. Concordance of specific human papillomavirus types in sex partners is more prevalent than would be expected by chance and is associated with increased viral loads. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41:612–20. doi: 10.1086/431978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Chaturvedi AK, Graubard BI, Pickard RK, Xiao W, Gillison ML. High-Risk Oral Human Papillomavirus Load in the US Population, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2009-2010. J Infect Dis. 2014 doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Gillison ML, D'Souza G, Westra W, Sugar E, Xiao W, Begum S, et al. Distinct risk factor profiles for human papillomavirus type 16-positive and human papillomavirus type 16-negative head and neck cancers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:407–20. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Kissinger P, Rice J, Farley T, Trim S, Jewitt K, Margavio V, et al. Application of computer-assisted interviews to sexual behavior research. Am J Epidemiol. 1999;149:950–4. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Wadsworth J, Johnson AM, Wellings K, Field J. What's in a mean?- an examination of the inconsistency between men and women reporting sexual partnerships. Journal of the Royal Statistical Association. 1996;159:111–23. [Google Scholar]

- (36).Herrero R, Quint W, Hildesheim A, Gonzalez P, Struijk L, Katki HA, et al. Reduced prevalence of oral human papillomavirus (HPV) 4 years after bivalent HPV vaccination in a randomized clinical trial in Costa Rica. PLoS One. 2013;8:e68329. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0068329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Recommendations on the use of quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccine in males--Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), 2011 MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60:1705–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Lowy DR, Schiller JT. Reducing HPV-associated cancer globally. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2012;5:18–23. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-11-0542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).National Cancer Institute . A Report to the President of the United States from the President's Cancer Panel. Bethesda, MD: 2014. Accelerating HPV Vaccine Uptake: Urgency for Action to Prevent Cancer. [Google Scholar]

- (40).Stanley M. HPV vaccination in boys and men. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2014:10. doi: 10.4161/hv.29137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.