Abstract

We expand the spectroscopic utility of a well-known infrared and fluorescence probe, p-cyanophenylalanine, by showing that it can also serve as a pH sensor. This new application is based on the notion that the fluorescence quantum yield of this unnatural amino acid, when placed at or near the N-terminal end of a polypeptide, depends on the protonation status of the N-terminal amino group of the peptide. Using this pH sensor, we are able to determine the N-terminal pKa values of nine tripeptides and also the membrane penetration kinetics of a cell-penetrating peptide. Taken together, these examples demonstrate the applicability of using this unnatural amino acid fluorophore to study pH-dependent biological processes or events that accompany a pH change.

1. INTRODUCTION

Recently, p-cyanophenylalanine (PheCN) has emerged as a convenient and versatile site-specific fluorescence reporter for various biochemical and biophysical studies [1]. The broad spectroscopic utility of this unnatural amino acid, which is a structural derivative of tyrosine (Tyr) or phenylalanine (Phe) [2], stems from the fact that its fluorescence quantum yield and lifetime are sensitive to environment [3], as well as its easy incorporation into peptides and proteins [4]. For example, dehydration leads to a significant decrease in the fluorescence intensity of PheCN, thus making it a useful probe of processes that involve exclusion of water, such as protein folding [5,6], binding [7,8], aggregation [9–11], and interaction with membranes [12–15]. In addition, the fluorescence quantum yield of PheCN can be modulated by various metal ions [16] and several amino acid sidechains [17–21]. In particular, its fluorescence can be quenched by a nearby tryptophan (Trp) residue via the mechanism of fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) [22–24]. Since this FRET pair has a Förster radius of approximately 16 Å, it has become a very useful tool to probe protein conformational changes over a relatively short distance [25]. Furthermore, Raleigh and coworkers have shown that the fluorescence intensity of PheCN, when placed at or near the N-terminus of a peptide, depends on the protonation status of the N-terminal amine group of the peptide [26]. However, the potential utility of this pH dependence of the PheCN fluorescence has not been demonstrated. Herein, we show that this unnatural amino acid can be used as a pH sensor to study pH-dependent biological processes or events that accompany a pH change. Specifically, we carry out two experiments to demonstrate the utility of PheCN fluorescence as a pH sensor; in the first one, we use it to determine the N-terminal pKa values of a series of short peptides and, in the second one, we employ it to characterize the membrane penetration kinetics of a cell-penetrating peptide, the trans-activator of transcription (TAT) peptide derived from HIV-1 [27–30].

Several methods, including high voltage electrophoresis [31], circular dichroism (CD) [32–35] and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy [36,37], have been used to determine the N-terminal pKa values of unstructured or α-helical peptides [38]. However, due to various limitations, for instance the CD method relies on the peptide of interest to form a well-folded structure such as an α-helix, applying these methods in practice is not always feasible, straightforward or convenient. Since fluorescence measurements are easier and also accessible to most, if not all, biochemical and biophysical researchers, it would be advantageous to devise a method that allows determination of N-terminal pKa values of peptides and proteins via fluorescence spectroscopy.

Cell-penetrating peptides (CPPs) are short cationic peptides which can spontaneously translocate across cell membranes and, as such, are ideal vehicles to deliver exogenous cargos into cells [39]. In spite of many previous efforts, however, several aspects of the translocation actions of CPPs are not well understood or characterized. For example, measurements of the intrinsic membrane penetration kinetics of CPPs are often done by measuring the fluorescence signal of a dye molecule attached to the CPP of interest. However, the fluorescent dyes used in this type of studies are typically large in size and, consequently, may have a significant effect on the CPP’s penetration rate. Here we show, using TAT as an example, that this concern can be alleviated by using PheCN fluorescence as a probe to follow the kinetics of CPP membrane penetration. Specifically, we replaced the N-terminal Tyr residue of TAT with PheCN, (the resultant peptide is hereinafter referred to as FCN-TAT), which is expected to cause only a minimum perturbation to the peptide as Tyr and PheCN are similar in size, and we exploited the pH-dependence of the PheCN fluorescence to quantitatively assess the penetration kinetics of TAT across a model membrane [40]. Interestingly, we find that under our experimental conditions TAT first translocates across the membrane on a timescale of minutes and then causes membrane leakage on a timescale of hours.

Experimental

Peptide synthesis and sample preparation

Peptides were synthesized on a PS3 automated peptide synthesizer (Protein Technologies, MA) using standard 9-fluorenylmethoxy-carbonyl (Fmoc) solid phase synthesis protocols and Fmoc-protected amino acids from either Bachem Americas (Torrence, CA) or AnaSpec (Fremont, CA). Before use, all peptide samples were further purified by reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography and verified by mass spectrometry. All peptide samples used in the pH titration measurements were prepared by dissolving lyophilized peptides into either acidic (25 mM H3PO4) or basic (25 mM NaOH) Millipore water, and the final concentration of each sample (20 μM) was determined optically using the absorbance of PheCN at 280 nm and a molar extinction coefficient of 850 M−1 cm−1 [7].

Fluorescence measurement and pH titration

Fluorescence spectra of the PheCN-containing peptides were measured at 25 °C on a Fluorolog 3.10 spectrofluorometer (Horiba, NJ) using a 1 cm quartz cuvette, a spectral resolution of 1 nm, an excitation wavelength of 275 nm, and an integration time 1 s/nm. During a specific pH titration experiment, the concentration of the peptide under consideration was maintained at 20 μM and the pH of the solution was varied between 2 and 12. This was achieved by mixing two 20 μM peptide stock solutions, one prepared in 25 mM H3PO4 and the other in 25 mM NaOH aqueous solution, in a cuvette at an appropriate volume ratio to achieve the desired pH, which was further measured using a pH meter (Orion/ThermoScientific, MA) Additionally, in each case a background spectrum, obtained with the buffer solution, was subtracted. Because the shape of the PheCN fluorescence spectrum is insensitive to environment, only the peak intensity was used to generate the pH titration curves. To determine the N-terminal pKa of each peptide, the corresponding fluorescence titration curve was fit to the following equation:

| (1) |

where F(x) is the fluorescence intensity at pH x, bi and mi are the intercept and slope of the linear base lines (i = 1 for acidic and i = 2 for basic).

Measurement of the membrane penetration kinetics of FCN-TAT

The 100-nm, large unilamellar vesicles (LUVs) used in the peptide penetration experiments were composed of either 100% DOPG or a mixture of DOPC, DOPG and cholesterol (3:1:1) and prepared following previously published procedures [41] from stock solutions of the respective lipids (purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids Inc., AL). Briefly, the respective lipid solution in chloroform was first dried under a flow of nitrogen, allowing a lipid film to form, which was followed by a 30-minute lyophilization to remove any remaining solvent. The resultant lipid film was then rehydrated with Millipore water and the pH of the sample was adjusted to 3.5 – 4.0 using H3PO4 and NaOH. This sample was then subjected to seven rounds of slow vortexing, freezing and thawing to form LUVs. The resulting vesicle solution was then extruded 11 times through an extruder (Avanti Polar Lipids Inc., AL) equipped with a 100 nm membrane. After extrusion, the LUV solution was diluted to 100 μM (lipid concentration) with Millipore water and the pH was adjusted between 10.0 – 10.5 with H3PO4 and NaOH. This process resulted in LUV’s with acidic pH inside the vesicle and basic pH outside. All LUV solutions were stored at 4°C and used within one week after preparation.

The membrane penetration kinetics of FCN-TAT was initiated by manually adding an appropriate aliquot of a concentrated peptide solution (350 μM, pH 7.0) to a 2.0 mL LUV solution described above. The final peptide concentration was 1.0 μM, resulting in a 1:100 peptide to lipid ratio. The time dependent fluorescence intensity of FCN-TAT at 298 nm was collected at 25 °C using the time based acquisition function of the Fluorolog 3.10 spectrofluorometer with time intervals of 2 seconds for the first 1,000 seconds, then every 10 seconds for the next 10,000 seconds and then 100 seconds for the remainder of the experiment. These data were then binned and the initial kinetic phase corresponding to the membrane penetration process was fit to a single-exponential function. To remove the contribution of water’s Raman scattering to the fluorescence signal, most of the kinetic traces were collected using an excitation wavelength of 240 nm. In other cases, an excitation wavelength of 275 nm was used. The pH of the solution was recorded throughout the duration of the experiment.

The fluorescence quenching assay used to estimate the timescale of membrane leakage was modified from a liposome flux assay [42]. Briefly, the LUVs were prepared using the abovementioned procedures, with the exception that a membrane impermeable fluorescent dye, pyranine (Alfa Aaser, MA), was added to the lipid solution. The concentration of pyranine was 4 μM in phosphate buffer (pH 7.5, 30 mM sodium phosphate and 100 mM NaCl). After extrusion of the lipid solution, the dye molecules that were not encapsulated inside LUVs were separated from the LUVs by passing the mixture through a pD-10 column (GE Healthcare, NJ). The dye-encapsulated LUV solution was then diluted into the same phosphate buffer that also contains 25 μM p-xylene-bis-pyridinium bromide (DPX) (Sigma-Aldrich, MO), a pyranine fluorescence quencher, to yield a final lipid concentration of 100 μM. The pyranine fluorescence was excited at 417 nm (isosbestic point) and monitored at 515 nm with and without the presence of FCN-TAT peptide.

Results and Discussion

Effect of the N-terminal amine group on PheCN fluorescence

Previous studies has suggested that the fluorescence of a PheCN residue, at or near the N-terminus of a peptide, can be significantly quenched by the deprotonated neutral form of the N-terminal amino group [16,26]. To further validate this notion, we measured the PheCN fluorescence spectra of a tripeptide consisting of glycine (G) and PheCN (FCN) with a sequence of GFCNG-CONH2, having either a free amino N-terminal end (the corresponding peptide is hereafter referred to as GFCNG) or an acetylated N-terminus (the corresponding peptide is hereafter referred to as *GFCNG). As shown (Figure 1), the PheCN fluorescence intensity of GFCNG shows a drastic decrease when the pH of the peptide solution is increased from 2.1 to 10.0. As the N-terminal pKa of peptides is typically smaller than 9.0 and, thus, at pH 10.0 the N-terminus of GFCNG is expected to be deprotonated, this result suggests that the N-terminal amino group is an effective quencher of the PheCN fluorescence in this case. In support of this conclusion, the PheCN fluorescence of *GFCNG does not show such a pH dependence within the pH range studied (Figure 1 inset). Taken together, these results indicate that a PheCN residue, when placed at the second position in a peptide sequence, can be used as a pH sensor.

Figure 1.

Normalized PheCN fluorescence spectra of GFCNG obtained at different pH values, as indicated. Shown in the inset are the normalized PheCN fluorescence spectra of *GFCNG (i.e., the N-terminal acetylated version of GFCNG) collected under acidic and basic pH conditions.

To demonstrate its application in this regard, we first used PheCN fluorescence to determine the N-terminal pKa of GFCNG. As shown (Figure 2), the intensity of PheCN fluorescence of GFCNG displays a sigmoidal dependence on pH, characteristic of an acid-base titration. As expected, the peptide *GFCNG, whose N-terminus is acetylated, does not show such a transition. Further fitting the fluorescence titration curve of GFCNG to a two-state model (i.e., eq. 1) yielded a pKa of 7.99, which is similar to the N-terminal pKa (7.85) of the amino group of an antimicrobial peptide [36], melittin, which has a Gly residue at the N-terminus. Interestingly, as indicated (Figure 2), swapping of the first two amino acids in GFCNG (the resulting peptide is hereafter referred to as FCNGG) leads to a decrease in not only the N-terminal pKa value (i.e., 6.97) but also the quantum yield of PheCN fluorescence. The latter is suggestive of a fluorescence quenching mechanism that is electron transfer in nature.

Figure 2.

Normalized PheCN fluorescence intensity versus pH of three tripeptides, as indicated. In each case, the smooth line represents the best fit of the corresponding fluorescence titration curve to Eq. 1 and the resulting pKa value is listed in Table 1.

Determining N-terminal pKa values of a series of tripeptides

The results obtained with GFCNG and FCNGG indicate that the dynamic range of the PheCN as a pH sensor can be tuned by changing the identity of the first amino acid. To this end, we carried out acid-base titrations on eight additional peptides having the following sequence: NH2-(XFCNG)-CONH2, where X represents a different amino acid in each case. Specifically, we chose several amino acids with varying sidechain properties, including positively charged (K), negatively charged (D), polar (N, S, G), or nonpolar (G, M, P, V, A) sidechains, to demonstrate the sensitivity of the fluorescence of PheCN. As shown (Figure 3), the corresponding pH titration curves of these peptides measured via PheCN fluorescence intensity have similar sigmoidal shapes but different mid-points (i.e., pKa values). Indeed, the N-terminal pKa values of these peptides, determined by fitting the respective acid-base titrations curves to eq. 1, are spread over two units of pH, ranging from 6.7 to 8.6 (Table 1). In particular, the N-terminal pKa (7.99) of the AFCNG tripeptide agrees well with that (8.0) determined for two alanine-based pentapeptides (NH2-AAEAA-Ac and NH2-AAHAA-Ac [43]. Because of the scarcity of N-terminal pKa values of short peptides, however, making more comparisons with other studies is not possible. On the other hand, it is clear that the N-terminal pKa value of the XFCNG peptide is, in most cases, smaller than that determined for an α-helical peptide with the same N-terminal residue (Table 1), suggesting that the peptide structure has a significant effect on the electronic property of the N-terminal amino group. In addition, as indicated (Figure 4), except for the proline (P) and serine (S) variants, the N-terminal pKa values of other peptides show a weak linear correlation with those (i.e., pK2) of the corresponding free amino acids. While further confirmation is needed, the large deviation observed for proline and serine likely results from their interactions with the PheCN sidechain. Regardless of the exact mechanism that controls the N-terminal pKa values of these tripeptides, the data in Figure 3 indicates that by changing the N-terminal residue, the useful dynamic range of PheCN fluorescence can be extended over five units of pH, from approximately 5 to 10.

Figure 3.

Normalized PheCN fluorescence intensity versus pH of XFCNG peptides, as indicated by the X amino acid. Smooth lines correspond to the best fits of these fluorescence titration curves to Eq. 1 and the resulting pKa values are given in Table 1. In addition, the significantly decreased fluorescence intensity of MFCNG is due to the previously verified quenching effect of methionine sidechain toward PheCN fluorescence [26].

Table 1.

The N-terminal pKa value of the XFCNG tripeptide determined from the current experiment, the pK2 value of the corresponding free amino acid X [46], and the N-terminal pKa value ( ) of an α-helical peptide with X at the N-terminus [32]. The uncertainty of the measured pKa values is ±0.1.

| X | pKa |

|

pK2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 6.69 | 7.07 | 8.8 | |

| M | 7.04 | 7.83 | 9.2 | |

| K | 7.25 | 8.12 | 9.2 | |

| P | 7.28 | 8.85 | 10.6 | |

| V | 7.29 | 8.14 | 9.6 | |

| D | 7.70 | 8.25 | 10.0 | |

| A | 7.99 | 8.35 | 9.7 | |

| G | 7.99 | 8.51 | 9.8 | |

| S | 8.59 | 7.63 | 9.2 | |

|

| ||||

| FCNGG | 6.97 | 9.1 | ||

Figure 4.

Comparison between the N-terminal pKa of XFCNG with the pK2 of the corresponding free amino acid X. Except for proline and serine, a correlation (R2 = 0.98) between the pKa and pK2values exists for the amino acids studied.

Using PheCN fluorescence to probe the membrane-penetrating kinetics of TAT

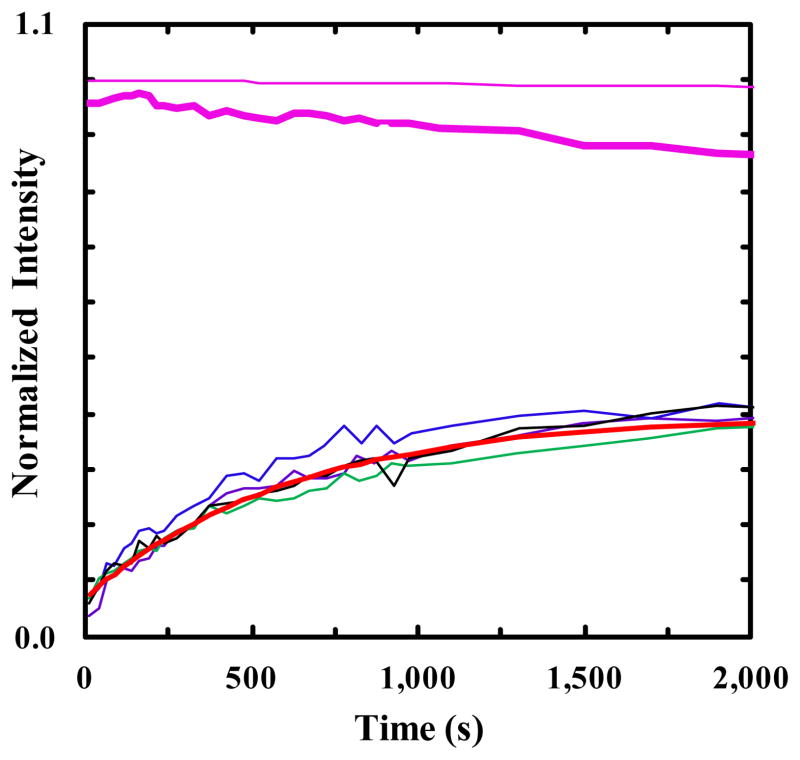

In this example, we seek to demonstrate that PheCN can serve as a pH sensor to monitor the rate of membrane penetration of CPPs. Specifically, we employed a well-studied CPP, TAT (YGRKKRRQRRR-CONH2) as our model peptide. As discussed above, the PheCN pH sensor was introduced via a Tyr to PheCN mutation. Previous studies have shown that the Tyr residue plays a minimal, if any, role in facilitating TAT translocation across membranes. Thus, we expect that the mutant peptide (i.e., FCN-TAT) will exhibit similar, if not identical, membrane penetration kinetics as the wild type peptide. As expected (Figure 5 inset), the PheCN fluorescence intensity of FCN-TAT depends on pH. To utilize this dependence to report the membrane penetration kinetics of FCN-TAT, we prepared a DOPG vesicle solution where the pH inside the vesicle was 3.5 and the pH outside the vesicle was 10.0. As shown (Figure 5), upon mixing this vesicle solution with a FCN-TAT solution at pH 10.0, the PheCN fluorescence increases with time in two well separated kinetic phases. This increase in PheCN fluorescence is consistent with the idea that a certain fraction of the peptide molecules has translocated across the DOPG membranes and, thus, are experiencing a significant decrease in pH. However, repetitive measurements indicate that while the first or fast kinetic phase is well defined and reproducible, the second phase appears to be ill-defined and occurs on a much longer timescale. These differences prompt us to assign the fast phase to peptide internalization in vesicles (or membrane penetration) and the slow one to membrane leakage. This is based on the notion that, unlike the penetration process, a number of peptide molecules need to work together, for example, through the formation of transmembrane pores [44,45], to cause the membrane to leak; as a result, the leakage kinetics are intrinsically more stochastic like and statistically more sensitive to the experimental uncertainties (e.g., variations in the peptide and vesicle concentrations). To confirm this assignment, we measured the pH of the peptide-vesicle solution at different reaction times and found that after the completion of the fast kinetics phase (e.g., at 50 minutes) the pH of the system was practically unchanged (i.e., 10.0 to 9.9), whereas after 5 hours the pH of the solution was decreased to 7.4. On the other hand, adding the GFCNG tripeptide to the same DOPG vesicle solution did not cause any appreciable change in the pH value after 12 hours. Thus, taken together these results support the aforementioned assignment. Moreover, the notion that the slow kinetic phase reports on peptide induced membrane leakage is further corroborated by the data obtained from a dye leakage experiment. As shown (Figure 5), under similar experimental conditions (i.e., same peptide and lipid concentrations) the fluorescence intensity of a dye (pyranine) that is initially encapsulated inside the DOPG vesicle shows a significant decrease (approximately 50% without counting photobleaching) over 10 hours, due to membrane leakage and consequently fluorescence quenching by a quencher (DPX) initially existing outside the vesicles. As indicated (Figure 6), the fast or peptide penetration kinetic phase can be fit by a single-exponential function with a time constant of 10.5 ± 2.2 minutes. This value is similar to those reported in the literature for TAT [40,46,47], providing further supporting evidence for our assignment.

Figure 5.

Four representative PheCN fluorescence kinetic traces (black, purple, green and blue) obtained upon mixing a FCN-TAT solution with a DOPG LUV solution. The excitation wavelength was 240 nm. The pink lines are the time-dependent fluorescence intensities of the pyranine dye initially encapsulated inside the DOPG vesicles obtained in the presence (thick line) and absence (thin line) of the FCN-TAT peptide and DPX quencher. In other words, the thin pink line measures the photobleaching rate of the pyranine dye, whereas the thick pink line reports the peptide induced membrane leakage kinetics. Shown in the inset is the normalized PheCN fluorescence of FCN-TAT as a function of pH.

Figure 6.

The first 2000-second portions of the same PheCN fluorescence kinetic traces in Figure 5. The red line represents the best fit of the averaged data of these four curves to a single-exponential function with a time constant of 10.5 ± 2.2 minutes.

Using 240 nm photons to excite the PheCN fluorescence may lead to undesirable heating effect. To verify that this is not the case, we also carried out fluorescence kinetic measurements using an excitation wavelength of 275 nm. As shown (Figure 7), the resultant penetration kinetics has a time constant of 12.8 ± 2.0 minutes, indicating that the photo-excitation induced heating affects minimally, if any, the kinetic results. Similarly, to better mimic eukaryotic cell membranes, we also conducted the penetration experiment using a ternary mixture of DOPC, DOPG, and cholesterol [48,49]. As indicated (Figure 7), the FCN-TAT penetration kinetics obtained with the mixed lipid membrane are comparable to those measured with DOPG vesicle, with a time constant of 11.9 ± 1.5 minutes.

Figure 7.

The thin red line represents the FCN-TAT penetration kinetics obtained with DOPG LUVs and an excitation wavelength of 275 nm, and the thick and smooth red line represents the best fit of this kinetic trace to a single-exponential function with a time constant of 12.8 ± 2.0 minutes. The thin blue line represents the FCN-TAT penetration kinetics obtained with the ternary lipid membrane described in the text, and the thick and smooth blue line represents the best fit of this kinetic trace to a single-exponential function with a time constant of 11.9 ± 1.5minutes.

Conclusion

The unnatural amino acid, p-cyanophenylalanine (PheCN), has unique infrared (IR) and fluorescent properties. As such, it has been used as both IR and fluorescence probes in a wide range of applications. Here, we further show that, for peptides having a PheCN residue at or near the N-terminus, the neutral form of the N-terminal amino group is much more effective than the protonated form in quenching the PheCN fluorescence. As a result, such peptides can be used as pH sensors. By examining the pH-dependence of the PheCN fluorescence of nine tripeptides (i.e., X-PheCN-Gly, where X represents either Asn, Met, Lys, Pro, Val, Asp, Ala, Gly or Ser), we are able to show that the dynamic range of such pH sensors can be tuned to cover several units of pH as the N-terminal pKa of these peptides depends on the identity of the N-terminal amino acid. In addition, using TAT as an example, we demonstrate that the aforementioned pH-dependence of PheCN fluorescence can be exploited to measure penetration kinetics of cell-penetrating peptides across model membranes.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge financial support from the National Institutes of Health (GM-065978).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Ma J, Pazos IM, Zhang W, Culik RM, Gai F. Site-specific infrared probes of proteins. Annu Rev Phys Chem. 2015;357–377 doi: 10.1146/annurev-physchem-040214-121802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meloni S, Matsika S. Theoretical studies of the excited states of p-cyanophenylalanine and comparisons with the natural amino acids phenylalanine and tyrosine. Theor Chem Acc. 2014;133:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Serrano AL, Troxler T, Tucker MJ, Gai F. Photophysics of a fluorescent non-natural amino acid: p-Cyanophenylalanine. Chem Phys Lett. 2010;487:303–306. doi: 10.1016/j.cplett.2010.01.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schultz KC, Supekova L, Ryu Y, Xie J, Perera R, Schultz PG. A Genetically Encoded Infrared Probe. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:13984–13985. doi: 10.1021/ja0636690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aprilakis KN, Taskent H, Raleigh DP. Use of the novel fluorescent amino acid rho-cyanophenylalanine offers a direct probe of hydrophobic core formation during the folding of the n-terminal domain of the ribosomal protein L9 and provides evidence for two-state folding. Biochemistry. 2007;46:12308–12313. doi: 10.1021/bi7010674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Serrano AL, Waegele MM, Gai F. Spectroscopic studies of protein folding: Linear and nonlinear methods. Protein Sci. 2012;21:157–170. doi: 10.1002/pro.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tucker MJ, Oyola R, Gai F. A novel fluorescent probe for protein binding and folding studies: p-cyano-phenylalanine. Biopolymers. 2006;83:571–576. doi: 10.1002/bip.20587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tang J, Yin H, Qiu J, Tucker MJ, Degrado WF, Gai F. Using Two Fluorescent Probes to Dissect the Binding, Insertion, and Dimerization Kinetics of a Model Membrane Peptide. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:3816–3817. doi: 10.1021/ja809007f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marek P, Gupta R, Raleigh DP. The fluorescent amino acid p-cyanophenylalanine provides an intrinsic probe of amyloid formation. Chem biochem. 2008;9:1372–1374. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200800052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Du D, Liu H, Ojha B. Study protein folding and aggregation using nonnatural amino acid p-cyanophenylalanine as a sensitive optical probe. Methods in molecular biology (Clifton, NJ) 2013;1081:77–89. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-652-8_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marek P, Mukherjee S, Zanni MT, Raleigh DP. Residue-Specific, Real-Time Characterization of Lag-Phase Species and Fibril Growth During Amyloid Formation: A Combined Fluorescence and IR Study of p-Cyanophenylalanine Analogs of Islet Amyloid Polypeptide. J Mol Biol. 2010;400:878–888. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.05.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tang J, Signarvic RS, Degrado WF, Gai F. Role of Helix Nucleation in the Kinetics of Binding of Mastoparan X to Phospholipid Bilayers. Biochemistry. 2007;46:13856–13863. doi: 10.1021/bi7018404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Loll PJ, Upton EC, Nahoum V, Economou NJ, Cocklin S. The high resolution structure of tyrocidine A reveals an amphipathic dimer. Biochim Biophys Acta, Biomembr. 2014;1838:1199–1207. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2014.01.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu J, Strzalka J, Tronin A, Johansson JS, Blasie JK. Mechanism of Interaction between the General Anesthetic Halothane and a Model Ion Channel Protein, II: Fluorescence and Vibrational Spectroscopy Using a Cyanophenylalanine Probe. Biophys J. 2009;96:4176–4187. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.01.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tucker MJ, Tang J, Gai F. Probing the kinetics of membrane-mediated helix folding. J Phys Chem B. 2006;110:8105–8109. doi: 10.1021/jp060900n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pazos IM, Roesch RM, Gai F. Quenching of p-cyanophenylalanine fluorescence by various anions. Chem Phys Lett. 2013;563:93–96. doi: 10.1016/j.cplett.2013.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tucker MJ, Oyola R, Gai F. Conformational distribution of a 14-residue peptide in solution: A fluorescence resonance energy transfer study. J Phys Chem B. 2005;109:4788–4795. doi: 10.1021/jp044347q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Glasscock JM, Zhu Y, Chowdhury P, Tang J, Gai F. Using an amino acid fluorescence resonance energy transfer pair to probe protein unfolding: Application to the villin headpiece subdomain and the LysM domain. Biochemistry. 2008;47:11070–11076. doi: 10.1021/bi8012406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miyake-Stoner SJ, Miller AM, Hammill JT, Peeler JC, Hess KR, Mehl RA, Brewer SH. Probing Protein Folding Using Site-Specifically Encoded Unnatural Amino Acids as FRET Donors with Tryptophan. Biochemistry. 2009;48:5953–5962. doi: 10.1021/bi900426d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Taskent-Sezgin H, Chung J, Patsalo V, Miyake-Stoner SJ, Miller AM, Brewer SH, Mehl RA, Green DF, Raleigh DP, Carrico I. Interpretation of p-Cyanophenylalanine Fluorescence in Proteins in Terms of Solvent Exposure and Contribution of Side-Chain Quenchers: A Combined Fluorescence, IR and Molecular Dynamics Study. Biochemistry. 2009;48:9040–9046. doi: 10.1021/bi900938z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goldberg JM, Batjargal S, Petersson EJ. Thioamides as Fluorescence Quenching Probes: Minimalist Chromophores To Monitor Protein Dynamics. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:14718–14720. doi: 10.1021/ja1044924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Serrano AL, Bilsel O, Gai F. Native State Conformational Heterogeneity of HP35 Revealed by Time-Resolved FRET. J Phys Chem B. 2012;116:10631–10638. doi: 10.1021/jp211296e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wissner RF, Batjargal S, Fadzen CM, Petersson EJ. Labeling Proteins with Fluorophore/Thioamide Forster Resonant Energy Transfer Pairs by Combining Unnatural Amino Acid Mutagenesis and Native Chemical Ligation. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:6529–6540. doi: 10.1021/ja4005943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reif MM, Oostenbrink C. Molecular Dynamics Simulation of Configurational Ensembles Compatible with Experimental FRET Efficiency Data Through a Restraint on Instantaneous FRET Efficiencies. J Comput Chem. 2014;35:2319–2332. doi: 10.1002/jcc.23756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mintzer MR, Troxler T, Gai F. p-Cyanophenylalanine and selenomethionine constitute a useful fluorophore-quencher pair for short distance measurements: application to polyproline peptides. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2015;17:7881–7887. doi: 10.1039/c5cp00050e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Taskent-Sezgin H, Marek P, Thomas R, Goldberg D, Chung J, Carrico I, Raleigh DP. Modulation of p-Cyanophenylalanine Fluorescence by Amino Acid Side Chains and Rational Design of Fluorescence Probes of alpha-Helix Formation. Biochemistry. 2010;49:6290–6295. doi: 10.1021/bi100932p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hallbrink M, Floren A, Elmquist A, Pooga M, Bartfai T, Langel U. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta, Biomembranes. Biochim Biophys Acta, Biomembr. 2001;1515:101–109. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(01)00398-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shen D, Liang K, Ye Y, Tetteh E, Achilefu S. Modulation of nuclear internalization of Tat peptides by fluorescent dyes and receptor-avid peptides. Febs Letters. 2007;581:1793–1799. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.03.067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jones AT, Sayers EJ. Cell entry of cell penetrating peptides: tales of tails wagging dogs. J Controlled Release. 2012;161:582–591. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2012.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tseng YL, Liu JJ, Hong RL. Translocation of liposomes into cancer cells by cell-penetrating peptides penetratin and TAT: A kinetic and efficacy study. Mol Pharmacol. 2002;62:864–872. doi: 10.1124/mol.62.4.864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wallis M. pKa Values of α-Amino Groups of Peptides Derived from N-Terminus of Bovine Growth-Hormone. Biochimica Et Biophysica Acta. 1973;310:388–397. doi: 10.1016/0005-2795(73)90120-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chakrabartty A, Doig AJ, Baldwin RL. Helix capping propensities in peptides parallel those in proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:11332–11336. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.23.11332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Doig AJ, Baldwin RL. N- and C-Capping Preferences for all 20 Amino-Acids in α-Helical Peptides. Protein Sci. 1995;4:1325–1336. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560040708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wilcox W, Eisenberg D. Thermodynamics of Melittin Tetramerization Determined by Circular-Dichroism and Implications for Protein Folding. Protein Sci. 1992;1:641–653. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560010510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Goto Y, Hagihara Y. Mechanism of the Conformational Transition of Melittin. Biochemistry. 1992;31:732–738. doi: 10.1021/bi00118a014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhu LY, Kemple MD, Yuan P, Prendergast FG. N-Terminus and Lysine Side-Chain pKa Values of Melittin in Aquesous-Solutions and Micellar Dispersions Measured by 15N NMR. Biochemistry. 1995;34:13196–13202. doi: 10.1021/bi00040a035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brown LR, Lauterwein J, Wuthrich K. High Resolution H-1-NMR Studies of Self-Aggregation of Melittin in Aqueous Solution. Biochimica Et Biophysica Acta. 1980;622:231–244. doi: 10.1016/0005-2795(80)90034-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pace CN, Grimsley GR, Scholtz JM. Protein Ionizable Groups: pK Values and Their Contribution to Protein Stability and Solubility. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:13285–13289. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R800080200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zorko M, Langel U. Cell-penetrating peptides: mechanism and kinetics of cargo delivery. Adv Drug Delivery Rev. 2005;57:529–545. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2004.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Swiecicki J-M, Bartsch A, Tailhades J, Di Pisa M, Heller B, Chassaing G, Mansuy C, Burlina F, Lavielle S. The Efficacies of Cell-Penetrating Peptides in Accumulating in Large Unilamellar Vesicles Depend on their Ability To Form Inverted Micelles. Chem biochem. 2014;15:884–891. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201300742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Aurora TS, Li W, Cummins HZ, Haines TH. Preparation and Chracterization of Monodisperse Unilamellar Phospholipid Vesicles with Selected Diameters of from 300 to 600 nm. Biochimica Et Biophysica Acta. 1985;820:250–258. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(85)90118-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ma C, Polishchuk AL, Ohigashi Y, Stouffer AL, Schön A, Magavern E, Jing X, Lear JD, Freire E, Lamb RA, Degrado WF, Pinto LH. Identification of the functional core of the influenza A virus A/M2 proton-selective ion channel. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:12283–12288. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905726106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Grimsley GR, Scholtz JM, Pace CN. A summary of the measured pK values of the ionizable groups in folded proteins. Protein Sci. 2009;18:247–251. doi: 10.1002/pro.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ciobanasu C, Siebrasse JP, Kubitscheck U. Cell-Penetrating HIV1 TAT Peptides Can Generate Pores in Model Membranes. Biophys J. 2010;99:153–162. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.03.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Matsuzaki K, Yoneyama S, Murase O, Miyajima K. Transbilayer Transport of Ions and Lipids Coupled with Mastoparan X Translocation. Biochemistry. 1996;35:8450–8456. doi: 10.1021/bi960342a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Suzuki T, Futaki S, Niwa M, Tanaka S, Ueda K, Sugiura Y. Possible existence of common internalization mechanisms among arginine-rich peptides. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:2437–2443. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110017200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Richard JP, Melikov K, Vives E, Ramos C, Verbeure B, Gait MJ, Chernomordik LV, Lebleu B. Cell-penetrating peptides - A reevaluation of the mechanism of cellular uptake. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:585–590. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209548200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Feigenson GW. Phase diagrams and lipid domains in multicomponent lipid bilayer mixtures. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes. 2009;1788:47–52. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2008.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Marsh D. Cholesterol-induced fluid membrane domains: A compendium of lipid-raft ternary phase diagrams. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes. 2009;1788:2114–2123. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2009.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]