Abstract

Background and Aim

Auto-immune (AI) markers are reported in patients with steatohepatitis liver disease. However, their clinical significance is unclear.

Methods

Charts of patients due to alcohol (ALD) or non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) were stratified for anti-nuclear antigen (ANA>1:80), anti-smooth muscle antibody (ASMA>1:40), or anti-mitochondrial antibody (AMA>1:20). Study outcomes were patient survival and complications of liver disease.

Results

Of 607 patients (401 NAFLD), AI markers were available in 398 (mean age 50 ±15 y; 52% males; median body mass index (BMI) 38; 44% diabetic; 62% Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) as type of Steatohepatitis; median MELD score 9). A total of 78 (19.6%) patients were positive for AI markers without differences for ALD vs. NAFLD, cirrhosis vs. no cirrhosis, and NASH vs. no NASH. There were no differences for age; gender; BMI; cirrhosis at presentation; MELD score; endoscopic findings; and histology based on AI markers. Serum ALT was higher among patients with AI markers (65±46 vs. 59±66 IU/l; P=0.048). Data remained unchanged on analyzing NAFLD patients. None of the 11 ANA positive patients (1:640 in 4) showed findings of AI hepatitis. Biopsy in 3 AMA positive patients showed mild bile duct damage in one patient. On median follow-up of about 3 years, there were no differences on liver disease outcomes (ascites, encephalopathy, variceal bleeding), Hepatocellular carcinoma transplantation, and survival.

Conclusions

Auto-immune markers are frequently present in steatohepatitis liver disease patients. Their presence is an epiphenomenon without histological changes of autoimmune hepatitis. Further, their presence does not impact clinical presentation and follow-up outcomes.

Keywords: NAFLD, ALD, NASH, Fatty Liver, Autoimmunity

INTRODUCTION

Autoimmune markers have frequently been reported in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD).[1,2,3-7] Prevalence of these markers in NAFLD patients ranges from 12 to 48%. [1,2,3,7] Data are conflicting on the clinical and pathological importance of these markers in NAFLD patients. While some studies report no difference in the clinical implication of the autoimmune markers [3,7], others report worse outcomes in patients with positive autoimmune markers. [1,5] However, in the presence of high titers of autoimmune markers along with signs suggestive of autoimmune liver disease, AASLD recommends complete work up for autoimmune liver disease with a liver biopsy.[8] Patients with alcoholic liver disease (ALD) have similar histopathology as NAFLD with spectrum of disease progressing through stages of steatohepatitis. Studies describing prevalence and significance of autoimmune markers have been scarce in patients with alcoholic steatohepatitis. [9]. We performed this study to examine a) prevalence of auto-immune markers in well characterized patients with alcoholic liver disease (ALD) or with NAFLD and b) the impact of these markers on the disease progression and outcomes.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Study Design and Population

After obtaining permission form the institutional review board, a retrospective chart review was performed for all patients seen and managed at our center with a discharge diagnosis of ALD or NAFLD during 2007 and 2011. ALD was defined as liver disease in patients with alcohol use of more than 50gm/day in males and 30gm/day in females for more than five years after excluding other causes of liver disease.[10] NAFLD was defined with presence of fatty liver on liver imaging and/or elevated liver enzymes along with exclusion of other liver diseases and documented alcohol use of <10 g/d.[8] The study population was stratified based on presence or absence of autoimmune markers. Checking autoimmune markers for all 3 autoantibodies at our center is a part of the protocol assessment of etiology of liver disease. These autoimmune markers are checked using immunofluorescence technique and reported in titers. An individual patient was considered as positive for auto-immune markers if titers for anti-nuclear antigen (ANA) or anti-smooth muscle antibody (ASMA) or anti-mitochondrial antibody (AMA) were greater than 1:80, 1:40 and 1:20 respectively.

Outcomes

Study population on follow up after the diagnosis of respective disease was evaluated for the following study outcomes: death, development of cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), and decompensation of liver disease including esophageal variceal hemorrhage or ascites or porto-systemic encephalopathy. Cirrhosis was defined based on clinical, biochemical and imaging criteria and HCC was defined based on AASLD criteria.[11] For patients who were lost to follow up ,information from social security death index was used to confirm and collect data on patient survival.

Data Collection

Charts were reviewed for collection of data on: patient demographics (age, gender, and race), body mass index (BMI), history and amount of alcohol use, comorbidities (diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia), disease status at presentation (cirrhosis or no cirrhosis, HCC, or decompensation) with dates of onset, laboratory values for MELD score calculation, and autoimmune markers (ANA, ASMA, AMA) with their titers. Liver imaging findings were recorded for diagnosis of cirrhosis or HCC. Endoscopy findings were recorded for presence of portal hypertensive gastropathy and for esophageal varices. Portal hypertensive gastropathy was classified into absent, mild to moderate and severe. Varices were also categorized into absent, small and medium to large. Liver histology when available was recorded for components of NAFLD activity score and fibrosis stage. NAFLD activity score is the sum of scores of steatosis, lobular inflammation and ballooning ranging from 0-8.[12] Steatosis was graded based on proportion of hepatocytes containing fat as grade 0 (up to 5%); grade I (5 to <33%); grade II (33 to <66%); and grade III (>66%). Similarly, lobular inflammation and hepatocyte ballooning were graded as none, mild to moderate, or severe.(17) The stages of fibrosis were recorded as follows: Stage 0, no fibrosis; Stage 1, portal fibrosis; Stage 2 peri-portal fibrosis; Stage 3, bridging fibrosis; Stage 4, cirrhosis.[13] Liver biopsies of patients with positive auto-immune markers were examined for presence of auto-immune hepatitis and recorded for presence of portal infiltrates, interface hepatitis plasma cells, and bile duct damage.

Data Analyses

Baseline characteristics were compared for patients with ALD or with NAFLD using chi-square and student’s t tests for categorical and continuous variables respectively. Cumulative curves were generated comparing patients with and without auto-immune markers for outcomes after adjusting for age, gender, and MELD score from cox proportional hazard models. Patients lost to follow-up and those without the event at the time of their last follow-up were censored. P values <0.05 were considered significant. Analyses were performed using the Statistical Analyses Software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

A total of 607 patients were seen and managed between 2007 and 2011 for steatohepatitis related liver disease (401 NAFLD) at our center. Of these, 398 patients with information on autoimmune markers were included in the analysis. A total of 78 (19.6%) patients had any of the autoimmune marker positive. ANA was positive in 65 (16.3%), ASMA in 11 (2.8%) and AMA in 4 (1%) patients. Prevalence of autoimmune markers was similar comparing patients with NAFLD or ALD (Figure 1). Prevalence remained similar comparing patients with and without cirrhosis at the time of presentation (38 of 186 [20.4%] vs. 40 of 212 [18.9%], P=0.70). Further, among 87 NAFLD patients with available NASH activity score (NAS), there were no differences comparing patients with NASH (NAS>/=4) with those without NASH (NAS<4), 6 of 51 (11.8%) vs. 3 of 36 (8.3%), P=0.60.

Figure 1.

Prevalence of autoimmune markers among patients with steatohepatitis.

Baseline Characteristics

Patients with positive autoimmune markers when compared to those with absence of these markers were similar for age, gender and ethnicity. About 60% patients of patients had cirrhosis at the time of initial evaluation with no differences comparing patients with and without autoimmune markers. None of the patients with autoimmune markers positivity had HCC at presentation, compared to 9 (3%) patients negative for autoimmune markers having HCC at presentation. However, this difference was not statistically significant (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics comparing patients without and with autoimmune markers

| AI markers −ve (N=320) |

AI markers +ve (N=78) |

P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age in yrs. (mean ± SD) | 49±22 | 52±11 | 0.27 |

| Gender (% Males) | 53 | 48 | 0.46 |

| Race (% Caucasians) | 88 | 87 | 0.97 |

|

Cirrhosis at presentation

(% ) |

58 | 59 | 0.79 |

| HCC at presentation (%) | 3 | 0 | 0.16 |

| Mean corpuscular volume | 92±9 | 93±19 | 0.49 |

| ALT IU/l | 50±45 | 65±46 | 0.048 |

| AST IU/l | 59±66 | 66±43 | 0.41 |

| AST/ALT ratio | 1.36±0.8 | 1.4±0.7 | 0.49 |

| Albumin mg/dL | 3.6±2 | 3.4±0.7 | 0.29 |

| MELD Score | 9±8 | 9±7 | 0.51 |

| IgG mg/Dl | 1706±2362 | 1624±842 | 0.82 |

| % IgG >ULN IgG | 7.3 | 7.7 | 0.17 |

AI: Auto-immune; HCC: Hepatocellular carcinoma; MELD: Model for end-stage Disease; ALT: Alanine aminotransferase; AST: Aspartate aminotransferase; ULN: Upper limit of normal; IgG: Immunoglobulin G

Laboratory Findings

Laboratory values were similar comparing patients with and without autoimmune markers for mean corpuscular volume, serum albumin, and MELD score. Serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) values were higher among patients with positive autoimmune markers (65±46 vs. 59±66 IU/l; P=0.048) without any differences on aspartate aminotransferase (AST) or AST/ALT ratio (Table 1). Serum immunoglobulin G values were similar in the two groups with about 7% of patients in each group having values above the upper limit of normal. Data remained unchanged on analysis of 266 NAFLD patients with differences on serum ALT levels (93±19 vs. 89±6; P=0.02) and other baseline characteristics being similar comparing patients with and without autoimmune markers.

Endoscopic Findings

Endoscopy findings were available on194 patients with cirrhosis (38 positive for autoimmune markers) only. About 57% of patients had portal hypertensive gastropathy and 38% had presence of esophageal varices. There were no differences in the prevalence of or severity of these endoscopic findings comparing patients with and without autoimmune markers (Figure 2). Again, on analyzing 142 NAFLD patients, data remained unchanged.

Figure 2.

Endoscopic findings among patients with steatohepatitis comparing patients without (Gray bars) and with (Black bars) autoimmune markers. Upper panel shows findings of portal hypertensive gastropathy and lower panel shows findings of esophageal varices.

Histological Findings

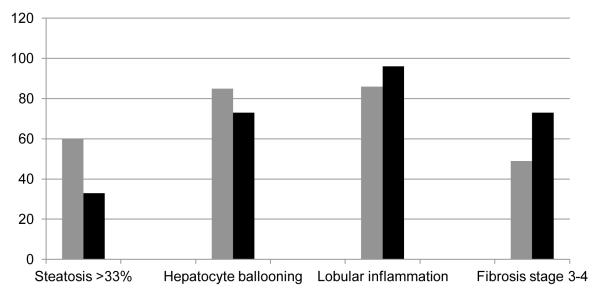

Liver histology was available in 116 (15 positive for autoimmune markers) patients. About 73 % (11 of 15) patients with positive autoimmune markers had advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis compared to 49% of patients without autoimmune markers; P=0.11 (Figure 3). Data on components of NAFLD activity score (NAS) was available for 108 (15 positive for autoimmune markers) patients. Moderate to severe steatosis was more prevalent among patients without autoimmune markers (66 vs. 33%; P=0.02) with no differences on other components of hepatocyte ballooning or lobular inflammation (Figure 3). NAFLD activity score was similar in the two groups (3.8±1.7 vs. 3.5±1.5; P=0.34).

Figure 3.

Histological findings comparing patients without (Gray bars) and with (black bars) autoimmune markers.

Liver biopsies on patients with positive autoimmune markers were further reviewed for findings of autoimmune hepatitis or primary biliary cirrhosis (Table 2). Of the 11 ANA positive (titers 1:640 in 4) patients with available histological findings, portal infiltrate was present in 7 patients and was of moderate degree in 2 patients. The infiltrate consisted on plasma cells in only one patient. This patient also had evidence of interface activity and was histologically diagnosed as probable autoimmune hepatitis with ANA of 1:160 and negative ASMA and AMA (Table 2). She was started on corticosteroids at an outside hospital. After being evaluated at our center, she was diagnosed to not have autoimmune hepatitis and steroids were discontinued. Another patient had histological evidence of bile duct damage and interface activity. There was no other evidence of primary biliary cirrhosis in this patient with negative AMA and normal alkaline phosphatase value (Table 2). Of three AMA positive patients with available histology, two had no evidence of primary biliary cirrhosis on biopsy and also had normal alkaline phosphatase levels. Third patient with AMA titer of 1:640 had minimal bile duct damage but had normal alkaline phosphatase. This patient was diagnosed with primary biliary cirrhosis was treated with ursodeoxycholic acid.

Table 2.

Histology details among patients with steatohepatitis liver disease and positive autoimmune markers

| ANA titer |

ASMA titer |

AMA titer |

Portal infiltrate |

Plasma cell infiltrate |

Bile duct damage |

Interface activity |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1:320 | <1:20 | <1:20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 1:160 | <1:20 | <1:20 | Mild | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | 1:640 | <1:20 | <1:20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | 1:160 | <1:20 | <1:20 | Moderate | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 5 | 1:1280 | 1:20 | <1:20 | Mild | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 | 1:160 | <1:20 | <1:20 | Moderate | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 7 | 1:160 | <1:20 | <1:20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 8 | 1:640 | 1:40 | <1:20 | Mild | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 9 | 1:320 | <1:20 | <1:20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 10 | 1:320 | <1:20 | <1:20 | Mild | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 11 | 1:1280 | 1:20 | <1:20 | Mild | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 12 | 1:80 | 1:20 | 1:160 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 13 | 1:80 | 1:20 | 1:640 | Mild | 0 | Minimal | 0 |

| 14 | 1:80 | 1:20 | 1:80 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

ANA: Anti-nuclear antigen; ASMA: Anti-smooth muscle antibody; AMA: Anti-mitochondrial antibody

Outcomes and Patient Survival

On a median follow up of about 3 years, there were no differences on development of liver related events (ascites, variceal bleeding, or encephalopathy), HCC, and overall patient survival, when patients with and without autoimmune markers were compared (Table 3). Among 212 patients without cirrhosis at presentation, autoimmune marker positivity did not increase odds for development of cirrhosis after controlling for age, gender, and Charlston comorbidity index with OR (95% CI): 1.32 (0.69-2.55). Age remained a predictor for development of cirrhosis [1.04 (1.02-1.06)], without impact of gender or comorbidity index. Similar analysis on NAFLD patients produced similar results. A total of 11 of 265 (4.2%) NAFLD patients received liver transplantation on follow up with no differences comparing patients with and without autoimmune markers (2 of 44 vs. 9 of 221 respectively; P=0.34).

Table 3.

Outcomes and survival comparing patients without and with autoimmune markers

| Autoimmune marker negative |

Autoimmune markers positive |

Median time (Yrs.) |

Log Rank P |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Death | 10 | 22 | 3.3 vs. 3 | 0.34 |

| HCC | 8 | 0 | 3.1 vs. 3 | 0.18 |

|

Variceal

bleeding |

15 | 20 | 3 vs. 2.8 | 0.99 |

| Ascites | 38 | 56 | 2.1 vs. 1.8 | 0.82 |

| Encephalopathy | 38 | 52 | 2.8 vs. 2.4 | 0.38 |

HCC: Hepatocellular carcinoma

DISCUSSION

Main findings of this retrospective study are a) auto-immune markers are present in about 20% of patients with steatohepatitis related liver disease, b) prevalence of these markers is similar among patients with alcoholic liver disease compared to patients with NAFLD, c) presence of auto-immune markers does not impact the clinical presentation and is not associated with changes of auto-immune hepatitis on liver histology, and d) presence of these markers does not influence the natural history and course of disease on follow up.

Prevalence of auto-immune markers has been shown to vary from 12 to 48% among various studies.[1,2,3,4,7] Our study with prevalence rate of about 20% is consistent with these data. Prevalence in this study was similar in both alcoholic liver disease and NAFLD patients. Although, presence of auto-immune markers has been reported in other liver diseases,[1,4,14] ours is the first study of their presence in patients with alcoholic liver disease. The data on impact of these auto-immune markers on the outcome of liver disease is conflicting with some studies reporting no impact,[3,7] while others showing worse outcomes in the presence of auto-immune markers.[1,5] Our results showing no impact of thee markers on the liver disease outcomes are similar to data reported by Vuppalnchi [7] and Cotler.[3]

The results of our study suggest that the presence of auto-immune markers among characterized patients with steatohepatitis related liver disease is likely an epiphenomenon and not a representation of underlying auto-immune hepatitis. Among 11 patients in this study with positive auto-immune markers including 4 patients with high titers of ANA of 1:640 or above, there was no histological evidence of auto-immune hepatitis.

Our study has limitations of a retrospective study with selection bias and is also limited to one center. These findings need confirmation from other centers and in larger prospective studies for their generalizability. Until then, liver biopsy may be considered to evaluate for underlying auto-immune liver disease among uncertain cases for diagnosis of steatohepatitis related liver disease as is also recommended by the AASLD.[8] Strict case definition and accurate characterization of alcoholic liver disease and NAFLD is strength of this study.

In summary, auto-immune markers are frequently present among patients with steatohepatitis related liver disease. These auto-immune markers do not impact the presentation and course of liver disease. Non-specific antigenic stimulation through the gut-liver axis may probably be mediating this epiphenomenon. However, the exact mechanism remains unknown and needs to be investigated.

Acknowledgments

Funding: The study was not funded by any source

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: None of the authors have any conflicts to disclose

REFERENCES

- 1.Adams LA, Lindor KD, Angulo P. The prevalence of autoantibodies and autoimmune hepatitis in patients with nonalcoholic Fatty liver disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:1316–1320. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.30444.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bacon BR, Farahvash MJ, Janney CG, Neuschwander-Tetri BA. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: an expanded clinical entity. Gastroenterology. 1994;107:1103–1109. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90235-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cotler SJ, Kanji K, Keshavarzian A, Jensen DM, Jakate S. Prevalence and significance of autoantibodies in patients with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2004;38:801–804. doi: 10.1097/01.mcg.0000139072.38580.a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Czaja AJ, Homburger HA. Autoantibodies in liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:239–249. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.20223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Loria P, Lonardo A, Leonardi F, et al. Non-organ-specific autoantibodies in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: prevalence and correlates. Dig Dis Sci. 2003;48:2173–2181. doi: 10.1023/b:ddas.0000004522.36120.08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Niwa H, Sasaki M, Haratake J, et al. Clinicopathological significance of antinuclear antibodies in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatol Res. 2007;37:923–931. doi: 10.1111/j.1872-034X.2007.00150.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tsuneyama K, Baba H, Kikuchi K, et al. Autoimmune features in metabolic liver disease: a single-center experience and review of the literature. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2013;45:143–148. doi: 10.1007/s12016-013-8383-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vuppalanchi R, Gould RJ, Wilson LA, et al. Clinical significance of serum autoantibodies in patients with NAFLD: results from the nonalcoholic steatohepatitis clinical research network. Hepatol Int. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s12072-011-9277-8. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chalasani N, Younossi Z, Lavine JE, et al. The diagnosis and management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: practice Guideline by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, American College of Gastroenterology, and the American Gastroenterological Association. Hepatology. 2012;55:2005–2023. doi: 10.1002/hep.25762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Laskin CA, Vidins E, Blendis LM, Soloninka CA. Autoantibodies in alcoholic liver disease. Am J Med. 1990;89:129–133. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(90)90288-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lian M, Hua J, Sheng L, Qiu de K. Prevalence and significance of autoantibodies in patients with alcoholic liver disease. J Dig Dis. 2013;14:396–401. doi: 10.1111/1751-2980.12057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Singal AK, Anand BS. Recent trends in the epidemiology of alcoholic liver disease. Clinical Liver Disease. 2013;2:53–56. doi: 10.1002/cld.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bruix J, Sherman M. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma: an update. Hepatology. 2011;53:1020–1022. doi: 10.1002/hep.24199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kleiner DE, Brunt EM, Van Natta M, et al. Design and validation of a histological scoring system for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2005;41:1313–1321. doi: 10.1002/hep.20701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brunt EM, Janney CG, Di Bisceglie AM, Neuschwander-Tetri BA, Bacon BR. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: a proposal for grading and staging the histological lesions. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:2467–2474. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.01377.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lenzi M, Bellentani S, Saccoccio G, Muratori P, Masutti F, Muratori L, et al. Prevalence of non-organ-specific autoantibodies and chronic liver disease in the general population: a nested case-control study of the Dionysos cohort. Gut. 1999;45:435–441. doi: 10.1136/gut.45.3.435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]