Abstract

Hypoparathyroidism is an uncommon endocrine deficiency characterised by low serum calcium, absent or inappropriately low parathyroid hormone and normal or high serum phosphorus levels. Parathyroid hormone is essential for calcium homoeostasis. Pregnancy and lactation are known for increased calcium requirement. They cause calcium stress as well as alter its metabolism. Hence, many abnormalities are expected in hypoparathyroidism during pregnancy and lactation. We report a case of pregnancy in postsurgical hypoparathyroidism, which is rarely encountered in antenatal clinics. We describe our clinical, biochemical and therapeutic experience of pregnancy and lactation in this patient with hypoparathyroidism.

Background

Parathyroid hormone (PTH) is essential for calcium homoeostasis. A low level of PTH causes decrease in intestinal calcium absorption, urinary reabsorption and skeletal resorption, resulting in hypocalcaemia.1 Calcium demand increases during pregnancy and lactation, and is met by adaptive physiological changes at the renal, intestinal and skeletal systems through various hormones.2 Co-existence of pregnancy and hypoparathyroidism makes calcium homoeostasis complex and generates dynamic calcium stress unless the demands are met by appropriate calcium and calcitriol supplementation. Incidence of pregnancy in hypoparathyroidism is unknown. Controversies exist at various levels starting from calcium demand in the first trimester to doses of calcitriol supplementation, as no clear cut management guideline exists.3

We report a case of pregnancy in post-thyroidectomy hypoparathyroidism managed with calcium and vitamin D supplementation without any adverse fetal or neonatal outcome.

Case presentation

A 38-year-old woman, gravida 2, para 1, a known case of post-thyroidectomy hypoparathyroidism for 4 years, stable on supplementation with calcium, vitamin D and l-thyroxine, was referred at 6 weeks of pregnancy for antenatal hormonal management, drug review and counselling. She had undergone her first delivery 8 years prior, uneventfully. Her pre-pregnancy intact PTH level was 12 pg/mL and calcium level of the previous year was in the range of 7.5–8.2 mg/dL; she had no serious intermittent symptoms. Her baseline drug intake at the time of reporting was 2 g of calcium carbonate, 400 IU of vitamin D3, 0.25 g of calcitriol and 100 g of l-thyroxine daily.

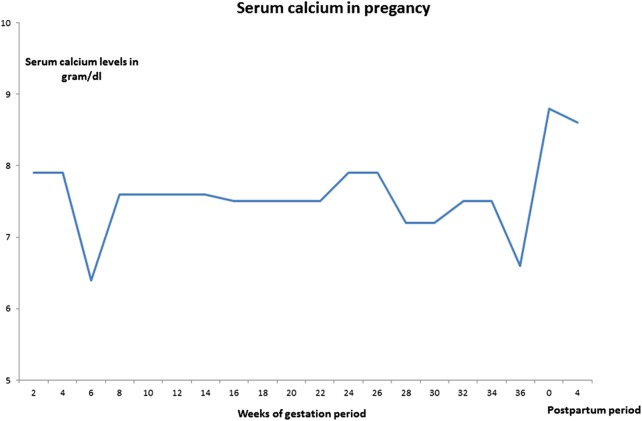

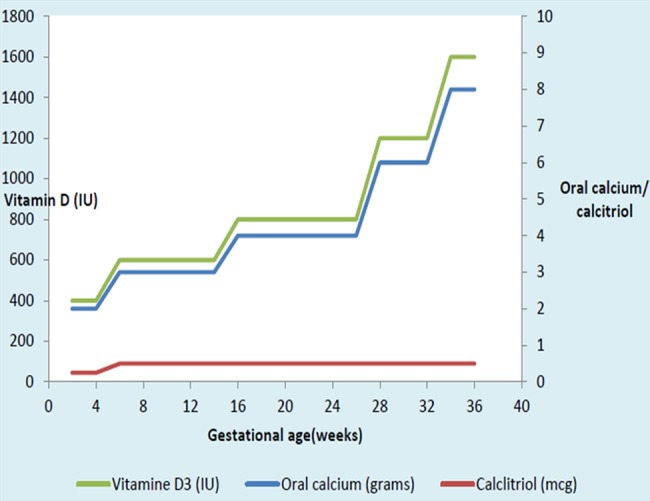

Her antenatal investigations were normal except for low calcium levels (6.4 mg/dL) at 6 weeks. Since she was asymptomatic, calcium and vitamin D3 supplementations were increased, an antiemetic was started for excessive vomiting and serum calcium was brought to 7.6 mg/dL. The patient was aware of early neuromuscular symptoms of hypocalcaemia. Pregnancy-induced biochemical changes were explained and she was counselled. Her fetal anomaly and growth scans were unremarkable, and fetal echocardiography was normal. Her blood glucose was within the normal range. Her antenatal period was otherwise uncomplicated. Periodic assessment of serum calcium and thyroid-stimulating hormone levels were carried out and doses of calcium, vitamin D analogue and l-thyroxine were adjusted. Serial 2–4 weeks of calcium monitoring is shown in figure 1 and adjusted drug doses are mentioned in figure 2. The patient needed dosage upregulation at 6, 16, 28 and 36 weeks. At 36 weeks of pregnancy, she was on 8 g of calcium carbonate (3.2 g of elemental calcium), 1600 IU of vitamin D3, 0.5 g of calcitriol and 187.5 g of l-thyroxine.

Figure 1.

Serum calcium in pregnancy.

Figure 2.

Oral calcium, vitamin D and calcitriol during pregnancy.

At 37 weeks of pregnancy, the patient developed fever, localised abdominal pain, the first episode of perioral twitching, and numbness of hands and feet. She was managed by slow intravenous injection of calcium gluconate and antibiotics. She then developed respiratory alkalosis and electrolyte imbalance, and was managed in intensive care unit (ICU) with injectable calcium gluconate, magnesium sulfate, potassium chloride and supportive care. Table 1 shows management during hospitalisation. Her ionised calcium level, which was 3.2 mg/dL, was brought to 4.7 mg/dL with intravenous and oral calcium administration.

Table 1.

Acute management of hypocalcaemia and electrolyte imbalance

| Admission day | Serum calcium in mg/dL | Ionic calcium in mg/dL | Serum magnesium in mg/dL | Serum potassium in mEq/L | Calcium gluconate (93 mg/ampule) | Other supplementation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First | 6.6 | – | 1.7 | – | 2 | – |

| Second | 6.7 | 3.2 | 1.8 | 4.1 | 4 | Inj Mgso4 |

| Third | 7.2 | 4.7 | 1.6 | 3.4 | – | Inj KCL |

| Fourth | 6.7 | – | 1.8 | 3.8 | 2 | – |

Outcome and follow-up

The patient was induced with prostaglandin E2 gel twice in view of oligohydramnios. During the intrapartum period, she presented with another episode of hypocalcaemia, which was managed with parenteral calcium gluconate. She had a normal delivery of a healthy 2.8 kg baby. Neonatal physical examination and neuromuscular behaviour was normal. The maternal lactation period was observed to have a high normal value of calcium; hence, elemental calcium and vitamin D3 were decreased by 400 mg and 200 IU, respectively. The patient continued to be asymptomatic 3 months postpartum.

Discussion

PTH is important for calcium regulation in the normal state. During pregnancy, fetal and maternal demand for calcium increases; in spite of an adaptive physiological mechanism, it requires additional calcium administration. Risk of hypocalcaemia and related complications are increased if deficiency of PTH coexists. Hypocalcaemia can be asymptomatic or it can present with a wide range of symptoms including cramps, tetany, seizures and congestive heart failure.1

In normal pregnancy, due to cellular hyperplasia and increase in maternal blood volume, total serum calcium levels decrease to low normal range. However, ionised calcium remains unchanged.4 An albumin-corrected serum level is important for calcium measurement in pregnancy. It was suggested that suppression of PTH to low or normal range occurs in the first trimester and gradually increases to mid-normal range by term.5 This happens in patients with a normal calcium store and intake. On the contrary, rise in PTH has been seen with low calcium intake, even in the first trimester.6 Studies have shown that low levels are found in the initial lactation period due to PTH-related protein (PTHrP) and increases at the time of weaning.4

Prolactin and human placental lactogen may act as calcitropic hormones during pregnancy by promoting synthesis of calcitriol through stimulating renal 1α-hydroxylase.7 The total calcitriol level increases in the first trimester itself and high levels are noted in the second and third trimesters. This coincides with increase in fetal demand.7 8 Postpregnancy, it reduces and remains in normal range during lactation with a small peak at the time of weaning.4

PTHrP is detected early in pregnancy but increases greatly during late pregnancy and puerperium. Its role in pregnancy as calcitropic hormone is uncertain. The breasts become accessory parathyroid during lactation, and secrete large amounts of PTHrP. Oestradiol and PTHrP act synergistically to increase calcium levels by enhancing bone resorption, and increase urinary calcium reabsorption during lactation.4

Post-thyroidectomy hypoparathyroidism suggests absence of thyroid, PTHs and calcitonin, which are essential for various biological metabolisms. Requirement of calcium in early pregnancy is controversial. This case report confirms increase in calcium and calcitriol requirement early in the pregnancy itself, as serum values were 6.4 mg/dL. We presume that excessive vomiting in the first trimester, and low calcium and vitamin D stores due to long standing pathology, caused this. Al Nozha reported two consecutive pregnancies in a hypoparathyroid patient, supporting increase in calcium and calcitriol demand during early pregnancy.3 It was reported that during normal pregnancy, ionised calcium remains unchanged and physiological drop of serum calcium levels are of no physiological significance. Kovacs4 reported increase in total calcitriol levels from the first trimester, however, free calcitriol does not increase until the third trimester. High calcitriol almost doubles the intestinal calcium absorption in early pregnancy, leading to positive calcium balance, and allows maternal skeletal tissue to store calcium before peak fetal demand appears during the third trimester. As our patient was asymptomatic, she was managed with oral increments of calcium and calcitriol. Her ionised calcium level was not checked during the asymptomatic period. Our aim was to keep serum calcium levels above 7.6 mg/dL and to keep the patient symptom-free.

At 37 weeks, she had symptomatic hypocalcaemia precipitated by fever and respiratory alkalosis, for which ICU attention was given. This is the first case report, to the best of our knowledge, mentioning respiratory alkalosis in pregnancy with hypoparathyroidism. There were many reasons of respiratory alkalosis; fever, pain, anxiety and hyperventilation were seen in our patient. Her acid–base and electrolyte management was carried out with intravenous administration of calcium gluconate, magnesium sulfate and potassium chloride, along with appropriate respiratory support in ICU.

Prostaglandin E2 (PG E2) is thought to increase serum levels of calcium by mobilising body stores of calcium.3 However, in the intrapartum period, after PG E2 instillation, our patient had early signs of tetany, which was managed by intravenous calcium gluconate.

Serum calcium was found above her average levels in lactation; hence, elemental calcium and vitamin D3 were reduced to 2.8 g and 1400 IU/day, respectively. Many studies suggested that requirement of oral calcium and calcitriol decreases in puerperium and lactation in hypoparathyroid as well as in normal women.2 9 This can be explained by increased PTHrP by a thousand fold during lactation, leading to inevitable skeletal resorption. Prolactin and low oestradiol levels during lactation also contribute to skeletal resorption. Increased calcium absorption for regulation of serum calcium concentration appears only with regaining of menstruation, which suggests normalisation of oestrogen levels.3

Inadequate calcium supplementation can produce hyperparathyroidism in the fetus, suggesting that the fetal parathyroid also plays a regulating role in calcium homoeostasis.10 11

Apart from classic neuromuscular symptoms of hypocalcaemia in inadequate calcium doses, obstetric complications are abortion, preterm labour and dysfunctional labour.12 Over-treatment with calcium can lead to hypercalciuria, nephrolithiasis, renal impairment and neonatal seizures.13 14 This suggests the need for periodic calcium monitoring and reduction of calcium supplementation if hypercalcaemia is noted. Fetal and neonatal mineralisation abnormality, intrauterine fractures, intracranial bleed and con-natal hyperparathyroidism have been noted with insufficient vitamin D supplementation; however, overtreatment with calcitriol causes suppression of fetal and neonatal parathyroids and has an additional concern of teratogenicity.10 Hence, optimum management of hypoparathyroidism is essential to prevent fetal and maternal complications. This is only possible with periodic clinical and biochemical examination, and appropriate drug supplementation.

Cholecalciferol (vitamin D3), a pro-drug, requires hepatic hydroxylation; it has a long half-life and small therapeutic range.15 We used vitamin D3 at a maximum dose of 1600 IU, without any adverse event. Although clinical experience with calcitriol is limited, calcium, cholecalciferol and calcitriol are considered safe as long as serum calcium levels are in the low normal range. Pitkin recommends a daily dose of calcitriol between 0.5 and 3 g/day in pregnancy.16 We used up to 1 μg/day of calcitriol and 8 g of calcium carbonate.

Recommended calcium is up to 9 g/day in pregnancy with hypoparathyroidism.17

Hypoparathyroidism is the only endocrine disorder where substitution of the deficient hormone is not well studied. Few case reports have mentioned continuous recombinant PTH infusion during pregnancy of iatrogenic hypoparathyroidism, and further trials are needed for safety of use.18

Conclusion

Calcium requirement in hypoparathyroidism differs during pregnancy and lactation. It is mainly the increase in intestinal absorption of calcium during pregnancy and skeletal resorption during lactation that maintains calcium homoeostasis. Guidelines for management of hypoparathyroidism in pregnancy do not exist. We give emphasis to serial monitoring, and daily calcium and calcitriol administration, as the mainstay of management. Exogenous calcium requirement increases from the beginning of pregnancy and reduces during lactation. Careful observation, anticipation and management of life-threatening complications are the key considerations in preventing undue maternal and fetal complications.

Learning points.

Calcium requirement increases in pregnancy, more so in the presence of maternal hypoparathyroidism. However, this needs close monitoring; if hypercalcaemia is noted, reduction in calcium and vitamin D dosage is warranted.

Careful clinical observation and laboratory monitoring are critical in the successful management of such patients.

Acute hypocalcaemic crisis has to be anticipated, and multidisciplinary and timely management must be instituted, for successful maternal and fetal outcomes.

Footnotes

Contributors: Contributed to active management during the patient's pregnancy and lactation, and prepared and drafted the manuscript.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Al-Azem H, Khan AA. Hypoparathyroidism. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 2012;26:517–22. doi:10.1016/j.beem.2012.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sweeney LL, Malabanan AO, Rosen H. Decreased calcitriol requirement during pregnancy and lactation with a window of increased requirement immediately post partum. Endocr Pract 2010;16:459–62. 10.4158/EP09337.CR [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Al Nozha OM, Malakzadeh-Shirvani P. Calcium homeostasis in a patient with hypoparathyroidism during pregnancy, lactation and menstruation. J Taibah Univ Med Sci 2013;8:50–3. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kovacs CS. Calcium and bone metabolism disorders during pregnancy and lactation. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 2011;40:795–826. 10.1016/j.ecl.2011.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dahlman T, Sjoberg HE, Bucht E. Calcium homeostasis in normal pregnancy and puerperium. A longitudinal study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 1994; 73:393–8. 10.3109/00016349409006250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Singh HJ, Mohammad NH, Nila A. Serum calcium and parathormone during normal pregnancy in Malay women. J Matern Fetal Med 1999;8:95–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kovacs CS, Kronenberg HM. Maternal-fetal calcium and bone metabolism during pregnancy, puerperium, and lactation. Endocr Rev 1997;18:832–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Salle BL, Berthezene F, Glorieux FH et al. Hypoparathyroidism during pregnancy: treatment with calcitriol. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1981; 52:810–13. 10.1210/jcem-52-4-810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mather KJ, Chik CL, Corenblum B. Maintenance of serum calcium by parathyroid hormone-related peptide during lactation in a hypoparathyroid patient. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1999;84:424–7. 10.1210/jcem.84.2.5486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Friedman WF, Mills LF. The relationship between vitamin D and the craniofacial and dental anomalies of the supravalvular aortic stenosis syndrome. Pediatrics 1969;43:12–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pitkin RM. Calcium metabolism in pregnancy: a review. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1975;121:724–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eastell R, Edmonds CJ, de Chayal RC et al. Prolonged hypoparathyroidism presenting eventually as second trimester abortion. BMJ (Clin Res Ed) 1985;291:955–6. 10.1136/bmj.291.6500.955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cooper MS. Disorders of calcium metabolism and parathyroid disease. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 2011;25:975–83. 10.1016/j.beem.2011.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Borkenhagen JF, Connor EL, Stafstrom CE. Neonatal hypocalcemic seizures due to excessive maternal calcium ingestion. Pediatr Neurol 2013;48:469–71. 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2013.02.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Callies F, Arlt W, Scholz HJ et al. Management of hypoparathyroidism during pregnancy—report of twelve cases. Eur J Endocrinol 1998;139:284–9. 10.1530/eje.0.1390284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pitkin RM. Calcium metabolism in pregnancy and the perinatal period: a review. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1985;151:99–109. 10.1016/0002-9378(85)90434-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bilezikian JP, Khan A, Potts JT Jr et al. Hypoparathyroidism in the adult: epidemiology, diagnosis, pathophysiology, target-organ involvement, treatment, and challenges for future research. J Bone Miner Res 2011;26:2317–37. 10.1002/jbmr.483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ilany J, Vered I, Cohen O. The effect of continuous subcutaneous recombinant PTH (1–34) infusion during pregnancy on calcium homeostasis—a case report. Gynecol Endocrinol 2013;29:807–10. 10.3109/09513590.2013.813473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]