Abstract

Internet-delivered interventions are emerging as a strategy to address barriers to care for individuals with chronic pain. This is the first large multicenter randomized controlled trial of Internet-delivered cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) for pediatric chronic pain. Participants included were 273 adolescents (205 females and 68 males), aged 11 to 17 years with mixed chronic pain conditions and their parents, who were randomly assigned in a parallel-group design to Internet-delivered CBT (n = 138) or Internet-delivered Education (n = 135). Assessments were completed before treatment, immediately after treatment, and at 6-month follow-up. All data collection and procedures took place online. The primary analysis used linear growth models. Results demonstrated significantly greater reduction on the primary outcome of activity limitations from baseline to 6-month follow-up for Internet CBT compared with Internet education (b = −1.13, P = 0.03). On secondary outcomes, significant beneficial effects of Internet CBT were found on sleep quality (b = 0.14, P = 0.04), on reducing parent miscarried helping (b = −2.66, P = 0.007) and protective behaviors (b = −0.19, P = 0.001), and on treatment satisfaction (P values < 0.05). On exploratory outcomes, benefits of Internet CBT were found for parent-perceived impact (ie, reductions in depression, anxiety, self-blame about their adolescent’s pain, and improvement in parent behavioral responses to pain). In conclusion, our Internet-delivered CBT intervention produced a number of beneficial effects on adolescent and parent outcomes, and could ultimately lead to wide dissemination of evidence-based psychological pain treatment for youth and their families.

Keywords: Randomized controlled trial, Chronic pain, Function, Adolescents, Pediatric, Cognitive behavioral therapy, Psychological treatment, Internet-delivered

1. Introduction

Chronic pain is estimated to affect 15% to 40% of children and occurs most commonly as head, abdominal, and musculoskeletal pain.21 Similar to the impact of pain in adults, a subset of these youth (5%-8%) are severely disabled by their pain problem16 and contribute to high health care costs.13 Unique social factors must be considered in treatment of children owing to known parent and family influences on pediatric chronic pain and disability.25 Treatments for youth are particularly needed to modify a potential trajectory of pain and disability from continuing into adulthood.18,39 In the most recent systematic review of psychological treatment for pediatric chronic pain,11 small to moderate effects were found for reductions in pain and disability after treatment across several chronic pain conditions.

However, even where effective psychological treatments exist, major barriers prevent families from receiving treatment because of limited access to trained professionals, geographical distance from pain clinics, and long waiting times. Availability of information and communication technology has expanded opportunities for reaching individuals with chronic pain remotely.26 Emerging evidence from studies primarily conducted in adults1,15 demonstrates that similar to face-to-face therapies, Internet and remote therapies also produce small beneficial effects on pain and disability; there is a small evidence base for remote therapies in youth with chronic pain.12 In our own preliminary study of Internet-delivered cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) in adolescents with chronic pain, we reported significant reductions after treatment in activity limitations and pain intensity compared with a wait-list control group.30 However, studies conducted to date in pediatric chronic pain populations have been limited by very small sample sizes, single-center recruitment, use of wait-list control groups, and short follow-up periods.

Thus, the objective of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness of an Internet-delivered CBT intervention compared with Internet education among a large multicenter cohort of adolescents with chronic pain recruited from pain centers across the United States and Canada. The Internet CBT program included separate interventions for adolescents and their parents directed at modifying behavioral coping, social/ environmental factors, and maladaptive cognitions. We followed the recommendations of PedIMMPACT24 and included validated measures in core outcome domains. Given that parents were targeted in the intervention, effects on parent outcomes were also examined.

We hypothesized that adolescents in families that received Internet CBT would report decreased activity limitations (primary outcome) compared with those receiving Internet education, assessed immediately after treatment and at 6-month follow-up. Furthermore, we hypothesized that adolescents who received Internet CBT would report reduced pain intensity, fewer depression and pain-specific anxiety symptoms, better sleep quality, and higher treatment satisfaction than adolescents who received Internet education would. On parent outcomes, we expected the Internet CBT group to show increased adaptive responses to pain and decreased miscarried helping compared with the Internet education group. In an exploratory analysis, we hypothesized that parent pain-related impact would be reduced in the group receiving Internet-delivered CBT compared with the group receiving Internet education.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants and setting

Participants included were 273 adolescents, aged 11 to 17 years, with chronic pain and their parents. The clinical trial was registered and the full protocol is available (Web-MAP2; Web-based Management of Adolescent Pain, ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier NCT13165471). Adolescents presenting as new patients were enrolled over a 3 and half year period from September 2011 to April 2014. There were 15 participating interdisciplinary pediatric pain clinics at academic medical centers across the United States and Canada. We received referrals from 14 of the centers and enrolled patients from 12 centers. The study was approved by the primary site’s Institutional Review Board and the Institutional Review Boards at each referring center.

We have published 1 article concerning trajectories of pain and function during the treatment period for adolescents randomized to the Internet CBT condition28; however, that article did not present treatment outcome analyses.

2.2. Inclusion/exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria consisted of (1) age 11 to 17 years, (2) chronic idiopathic pain present over the previous 3 months, (3) pain at least once per week, (4) parent report of pain interfering with at least 1 area of daily functioning, and (5) the adolescent received a new patient evaluation in one of the participating pain clinics.

Participants were excluded if (1) the adolescent had a serious comorbid psychiatric or chronic medical condition (eg, cancer), (2) the adolescent had a developmental disability per parent report, (3) the parent or adolescent was non-English speaking, (4) the family did not have regular access to the Internet on a desktop, tablet, phone, or laptop computer, or (5) the adolescent was not residing at home (eg, in an intensive pain rehabilitation program).

2.3. Recruitment

Providers at referring centers gave potential participants a flyer about the study and asked whether they were willing to be contacted through phone by study staff to undergo additional screening. Providers then entered potential participants’ contact information into the study Web site to securely transfer referral information to study staff. Potential participants could also contact study staff directly by calling a toll-free number provided on the study flyer. Study staff screened potential participants by telephone and then obtained verbal parent consent and adolescent assent for study participation.

2.4. Trial design and randomization

This study used a single-blinded multicenter, balanced (1:1) randomized parallel-group design. Assessments were completed online through our secure, password-protected Web site independently by adolescents and parents (using separate login procedures) at baseline before randomization, after completion of the 8 to 10 week intervention (immediately after treatment) and at 2 longer-term follow-up periods (6 and 12 months). Assessment of long-term outcomes at 12 months is ongoing and is not reported here. Randomization was implemented using a computer-generated randomization schedule to derive a randomization assignment to 2 treatment conditions in blocks of 4 for each ID number. The randomization assignment was programmed into the Web-MAP2 system. After pretreatment assessments, the group assignment was provided to each participant on the Web site with instructions on how to proceed during the treatment phase. Participants were blinded to whether they were receiving an active or control treatment. Because all study assessments were completed independently online, there was no possible examiner bias in outcome assessments.

2.5. Flow of participants through the study

Figure 1 shows a CONSORT flow diagram depicting the flow of study participants through each phase of the study. Referrals were received from 14 pain centers for 530 adolescents with chronic pain. Of those families who were referred to participate, 114 were excluded because they failed to meet inclusion criteria (eg, age out of range, had a chronic medical condition), 69 declined participation because of lack of time or interest, and 74 were unable to be reached to complete pretreatment assessments (passive refusals). The final sample consisted of 273 families.

Figure 1.

CONSORT flow diagram.

The 273 eligible families were randomly assigned to the Internet-delivered CBT arm (n = 138) or the Internet-delivered Education control arm of the trial (n = 135). Of the families who were randomized, 133 in the Internet CBT condition and 133 in the Internet education control condition received the allocated intervention (minimum of 4 modules completed by the parent–adolescent dyad). Eight participants (7 in the Internet CBT group and 1 in the Internet education group) did not complete the immediate posttreatment assessment. An additional participant (n = 1 in the Internet CBT group) did not complete the 6-month follow-up assessment. Four participants (n = 4 in the Internet CBT group) were subsequently excluded from analyses because of major life events that occurred during the trial (eg, death in the immediate family, parent in major car accident, parent had heart attack). Thus, 134 participants from the Internet CBT group and 135 participants from the Internet education group were included in final analyses.

2.6. Procedures

As part of their routine care, all enrolled participants received an initial evaluation in 1 of 12 collaborating interdisciplinary pain clinics. Subsequently, they may have received recommendations for treatment visits for physical therapy, psychology, and/or medication management. Standard care, as recommended by each participant’s pain clinic team, was not altered for the clinical trial. All study-related interventions were adjunctive to care provided by the pain clinics and were collected at the 12-month assessment.

Pretreatment assessments were completed on the study Web site, which included standardized study measures and a daily diary to rate pain intensity and activity limitations for 7 days. After the pretreatment assessment, participants were randomized to a treatment condition, either Internet-delivered CBT or Internet-delivered education. The treatment groups were provided with access to 2 different versions of a Web program, Web-based Management of Adolescent Pain (Web-MAP2) that provided either CBT or Pain Education.

2.6.1. Internet-delivered pain education control group

The pain education control group served as an attention control condition, equalizing time, attention, and computer usage. The control version of the Web-MAP study Web site had 2 functional components: (1) modules with information compiled from publicly available educational Web sites about pediatric chronic pain management (eg, National Headache Foundation, etc), and (2) diary and assessments. The control Web site did not provide access to behavioral and cognitive skills training. Adolescents and parents were instructed to log onto the Web program weekly at the same interval as the CBT group to read information about pediatric chronic pain. Reminders to access the Internet program were provided by study staff every 2 weeks during the treatment period. The Web program automatically recorded the number of logins and completed modules.

2.6.2. Internet cognitive-behavioral therapy condition

Adolescents and parents in the Internet CBT condition received access to the full Web-MAP2 program including education about chronic pain, training in behavioral and cognitive coping skills, instruction in increasing activity participation, and education about pain behaviors and parental operant and communication strategies using an engaging interactive format. Participants in the Internet CBT condition had access to 5 functional components of the Web program, (1) treatment modules, (2) assessments and daily diaries, (3) compass (audio files of relaxation strategies), (4) passport (progress tracker), and (5) a message center to correspond with their online coach. Access to the Web program remained in place for the duration of their study participation. Adolescents and parents were asked to complete 1 module per week, which were designed to be approximately 30 minutes in length. Total treatment duration was estimated at 9 hours per family consisting of 4 hours of adolescent modules, 4 hours of parent modules, and 1 hour of coach time.

The Web-MAP2 intervention consisted of 2 separate, password-protected Web programs, one for adolescent access and the other for parent access (https://www.webmap2.com) (see Fig. 2 for the homepage view). The program has a travel theme; the design and treatment content of Web-MAP2 was adapted from a pilot version of the program, which has been described elsewhere.30 Cognitive–behavioral, social learning, and family systems frameworks guided the interventions. There are 8 adolescent modules including: (1) education about chronic pain, (2) recognizing stress and negative emotions, (3) deep breathing and relaxation, (4) implementing coping skills at school, (5) cognitive skills (eg, reducing negative thoughts), (6) sleep hygiene and lifestyle, (7) staying active (eg, activity pacing, pleasant activity scheduling), and (8) relapse prevention.

Figure 2.

Web-MAP2 homepage.

Parent strategies included training in operant strategies, the importance of modeling, supporting independence, and enhancing communication with their adolescent. The 8 parent modules are: (1) education about chronic pain, (2) recognizing stress and negative emotions, (3) operant strategies I (using attention and praise to increase positive coping), (4) operant strategies II (using reward to increase positive coping; strategies to support school goals), (5) modeling, (6) sleep hygiene and lifestyle, (7) communication, and (8) relapse prevention.

Vignettes, videos of peer models, illustrations, and reinforcing quizzes are used throughout the program to increase interactivity. At some destinations, adolescents receive online postcards from previous places they have visited reminding them to practice skills. Adolescents and parents interact with the program by identifying personal goals and entering information, which allowed tailoring and personalization of information for weekly behavioral assignments. Adolescents and parents were asked to complete 1 module per week, designed to be analogous to weekly, clinician-delivered in-person CBT. Participants (youth and parents) spent time practicing skills and completing assignments in 6 of the 8 modules.

A message center allows communication between an online study coach and participant about each assignment. Adolescents and parents could also initiate messages to the coach at any time during the treatment period. Assignments were reviewed by 5 study coaches, one had a master’s degree and 4 were PhD level psychology postdoctoral fellows. All study coaches had previous experience in CBT. Before the randomized controlled trial (RCT), coaches completed a standard series of training tasks (readings, role play, and supervision) and used a previously developed online coaches’ manual to standardize their responses. During the trial, coaches were supervised by the first author (a licensed clinical psychologist with experience in CBT for pediatric chronic pain management) in their responses to assignments and messages submitted by adolescents and parents through ongoing message review. Coaches were instructed to spend no more than 5 minutes responding to assignments/messages. The coaches’ manual emphasized rapport building and encouragement of skills practice. Coaches responded to each message sent by participants. Responses included praise for skills practice (eg, “Nice job practicing guided imagery!”), strategies to overcome barriers to using skills (eg, “Try practicing guided imagery at the same time every day”), and content to build rapport (eg, “Did you do anything fun over the weekend?”).

2.7. Pretreatment measures

2.7.1. Sociodemographics

Caregivers completed a background form to identify the adolescent’s and parent’s race, parental marital status, parental education, parental employment, and family income.

2.7.2. Computer comfort

The Computer Equipment Comfort Rating (CECR),2 is a measure of user perceptions of comfort and distractions associated with using audiovisual equipment. We used the 7-items from the CECR specifically about use of computer equipment to assess adolescent and parent participants’ comfort with computer equipment and the Internet, current access, and usage. Items are rated on a 5-point scale (1 = not at all comfortable, 5 = completely comfortable) and summed for a total score ranging from 7 to 35. Cronbach alpha was 0.78 and 0.70 for parent and child report, respectively.

2.7.3. Treatment expectancies

After randomization, parents and adolescents completed a measure of treatment expectancies adapted from an existing measure of treatment expectations.36 This 10-item questionnaire asked youth and their parents to rate the likelihood that Internet treatment will lead to symptom improvement on 5-point rating scales (0 = not at all likely, 4 = extremely likely), with total scores ranging from 0 to 40. Cronbach alpha was 0.93 and 0.88 for parent and child report, respectively.

2.8. Primary outcome measure

2.8.1. Daily activity limitations

Daily activity limitations were assessed on the Web-MAP online diary with the prospective version of the Child Activity Limitations Interview (CALI),31 which is designed to assess school-age children’s perceived difficulty in completing typical daily activities because of pain. On the daily version of the measure, adolescents select the top 8 activities from a list of 21 activities (eg, going to school, sports, playing with friends, housework or chores, after-school practices, running, doing a hobby) that are most important in their day-to-day lives and that are difficult or bothersome because of pain. These 8 activities were programmed into the WebMAP daily diary. Adolescents were queried each day (1) whether the activity occurred and (2) how difficult the activity was to perform because of pain. If the adolescent did not have an opportunity to engage in a selected activity (eg, school was not in session), then a difficulty rating was not obtained on that activity. Adolescents provided difficulty ratings using a 5-point scale (0 = no difficulty, 4 = extremely difficult), with a range of 0 to 32 with higher scores indicating greater functional limitations. Average daily activity limitation scores across each assessment period were computed.

Reliability and validity of the CALI has been demonstrated in school-age children and adolescents with chronic pain recruited through pain clinics and specialty clinics (eg, rheumatology, hematology).31 Previous research on the prospective daily diary version of the CALI found evidence of responsivity to changes in children’s pain symptoms as evidenced by significant differences between mean CALI scores on days when pain was reported (mean = 8.2) compared with pain-free days (mean = 1.7, P < 0.001). Mean CALI difficulty ratings also increased with increasing pain severity.31

2.9. Secondary outcome measures

2.9.1. Pain intensity

The Web-MAP online diary was used for daily assessment of presence of pain and pain intensity for 7 days at each assessment period. Pain intensity was assessed using an 11 -point numerical rating scale (NRS) (0 = no pain, 10 = worst pain). The NRS has been recommended for assessment of pain intensity in adolescents with chronic pain.38 Average pain intensity across each assessment period was computed.

2.9.2. Emotional functioning

The Bath Adolescent Pain Questionnaire (BAPQ), developed specifically for adolescents with chronic pain, was used to assess emotional functioning in adolescents.6 The complete BAPQ contains 61 items that load onto 7 subscales: social functioning, physical functioning, depression, general anxiety, pain-specific anxiety, family functioning, and development. For the purposes of this trial, we used 2 subscales, Depression and Pain-specific anxiety, to assess adolescent emotional functioning. The measure uses a 2-week response frame and a 5-item Likert scale (0 = never, 4 = always). The Depression scale contains 6 items in which adolescents report their feelings and experiences of negative mood and sadness with scores ranging from 0 to 30. The Pain-specific Anxiety scale contains 7 items about worries or concerns about pain with scores ranging from 0 to 28. The BAPQ was developed for use in clinical populations of youth with chronic pain to evaluate treatment efficacy and has demonstrated good validity and test–retest reliability in outpatient pain samples.6 In this study, Cronbach alphas for the 2 subscales ranged from 0.83 to 0.84.

2.9.3. Sleep quality

Adolescent perception of sleep quality was measured by the Adolescent Sleep Wake Scale (ASWS).22 The ASWS is a 28-item self-report scale of sleep quality that is scored on a 6-point Likert scale (1 = always, 6 = never). Scores are summed to create a total score and 5 mean subscale scores: going to bed, falling asleep, maintaining sleep, reinitiating sleep, and returning to wakefulness. Scores range from 1 to 6 with higher scores indicating better sleep quality. The Total sleep quality score was used in analyses. The ASWS has been previously used in youth with comorbid sleep and medical conditions8 and has acceptable reliability and validity. In this study, Cronbach alpha was 0.87.

2.9.4. Parent responses to pain behaviors

Parents completed the Adult Responses to Children’s Symptoms (ARCS), which measures 3 types of parental responses to their child’s chronic pain.3,37,40 The Protect subscale assesses parents’ responses that either positively or negatively reinforce pain complaints. The Minimize scale assesses responses to child pain that are negative or not supportive. The Distract/Monitor scale assesses the parent’s tendency to inquire about pain or to distract the adolescent from pain. Responses are rated on a 5-point scale (0 = never, 4 = always). Responses are averaged to provide the subscale scores ranging from 0 to 4, with higher scores indicating more frequent use of that behavioral response style. The ARCS is a valid and reliable measure for use with parents of children with chronic pain seen in the outpatient setting.3,37,40 In this study, Cronbach alphas for the 3 subscales ranged from 0.65 to 0.86.

2.9.5. Miscarried helping

Adolescents and parents completed a version of the Helping for Health Inventory (HHI)14 adapted for chronic pain, HHI-Pain.9 The HHI-Pain is a 15-item questionnaire assessing miscarried helping (efforts to assist the adolescent with pain management that result in resistance). Items are rated on a 5-point scale (1 = rarely, 5 = always) and summed to create a total score ranging from 15 to 75. A higher score indicates greater use of miscarried helping. The HHI has demonstrated good reliability and validity in pediatric populations, including in outpatient samples of youth with chronic pain .91 n this study, Cronbach alpha was 0.84 for parent and child report.

2.9.6. Treatment acceptability and satisfaction

Youth and parents completed an adapted version of the Treatment Evaluation Inventory, short form (TEI-SF),19,20 after treatment and at follow-up. The TEI-SF is a 9-item self-report measure that assesses participant perceptions of a particular treatment program. Select items were adapted to be specific to pediatric pain (eg, “I find this treatment to be an acceptable way of dealing with children’s pain”). Items are rated on a 5-point scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree). Items are summed to create a total score ranging from 9 to 45, with higher scores indicating higher levels of satisfaction and acceptability of the treatment program. Per Kazdin,19 “moderate” satisfaction and acceptability of a treatment is indicated by a score of 27 or higher. This measure has demonstrated good reliability and validity20 across various child treatments. Cronbach alpha in the present study ranged from 0.81 to 0.82 for parent and child report.

2.9.7. Web site satisfaction

Satisfaction with the Web program was evaluated after treatment on a measure developed for this study. Adolescents and parents rated the Web site on 4 dimensions: appearance, ease of navigation, theme, and usefulness of overall content using a 6-point scale. The 4 individual items were examined separately with individual scores ranging from 0 to 5; higher scores indicate higher preference, likeability, or usefulness. Cronbach alpha in this study ranged from 0.70 to 0.71 for parent and child report.

2.9.8. Treatment engagement

Treatment engagement was assessed by the number of Internet modules completed by adolescents and their parents (0–16 total across the dyad), which was automatically recorded in the Web program.

2.9.9. Adverse events

Participants provided open-ended responses concerning adverse events occurring during the study at posttreatment and follow-up assessment.

2.10. Exploratory outcome measures

2.10.1. Parent pain-related impact

Parents completed the Bath Adolescent Pain Questionnaire–Parent Impact Questionnaire (BAPQ-PIQ17), a measure of the impact of parenting an adolescent with chronic pain. The BAPQ-PIQ is a 62-item questionnaire designed to assess the impact of caring for a child with chronic pain on parents’ functioning on 8 scales including: depressive symptoms, anxiety, pain catastrophizing, self-blame, partner relationship, social functioning, parental behavior, and parental role strain. Items are rated on a 5-point frequency response scale (0 = never, 4 = always) with higher scores indicating more impaired functioning for all subscales. The BAPQ-PIQ has demonstrated good reliability and validity among parents of youth with chronic pain.17 In the present study, Cronbach alphas for the 8 subscales ranged from 0.79 to 0.90.

2.11. Data analysis plan

Sample size calculations were performed on the primary outcome variable, activity limitations, based on results from our pilot trial of Web-MAP.30 Six-month follow-up was used as the primary end point. The study was powered for a final sample size of 240 participants accounting for up to 20% attrition.

All data analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS v21. Demographic characteristics were summarized using descriptive statistics. For categorical variables, frequency statistics are reported, and for continuous variables, we report means and SDs. Independent samples t tests with Bonferroni correction and χ2 analyses were conducted to confirm that randomization produced equivalent groups.

Primary hypothesis testing was conducted using the full sample with missing data handled through multilevel modeling procedures. Multilevel modeling is able to retain all observations, accommodates missing data, and accounts for repeated measures within subjects. Models were specified similar to procedures outlined by Shek and Ma.34 Time was treated as a categorical variable in the models, with baseline values specified as the reference point to test for the change in outcome variables from baseline to immediate posttreatment and baseline to 6-month follow-up. A full conditional model tested the effects of time, treatment group, group × time interactions, and covaried for adolescent race (dichotomized, 1 = Anglo-American, 0 = not Anglo-American) given baseline differences between the 2 treatment conditions (Table 1). The group × time interactions represent the change from baseline to posttreatment and the change from baseline to 6-month follow-up for the Internet CBT group relative to the Internet education group. The beta, P value, and effect size are reported for each interaction.

Table 1.

Adolescent and parent demographic characteristics at baseline (before randomization).

| Adolescent demographic characteristics | Total (n = 273) | CBT (n = 138) | Education (n = 135) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (% female) | 75.1 | 78.3 | 71.9 | χ2(1) = 1.50, P = 0.22 |

| Age (mean, SD) | 14.71 (1.62) | 14.63 (1.62) | 14.70 (1.72) | t(271) = −0.94, P = 0.35 |

| Race, % | χ2(1) = 10.86, P = 0.001 | |||

| Anglo-American | 85.0 | 92.0 | 77.8 | |

| Black or African American | 4.8 | 1.4 | 8.1 | |

| Hispanic/Latino | 3.7 | 1.4 | 5.9 | |

| Other | 5.0 | 4.5 | 6.0 | |

| Missing | 1.5 | 0.7 | 2.2 | |

| Primary pain location, % | χ2(3) = 2.06, P = 0.56 | |||

| Head | 7.0 | 8.0 | 5.9 | |

| Abdomen | 11.4 | 12.3 | 10.4 | |

| Musculoskeletal | 41.8 | 37.7 | 45.9 | |

| Multiple | 39.9 | 42.0 | 37.8 |

| Parent demographic characteristics | Total (n = 273) | CBT (n = 138) | Education (n = 135) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (% female) | 94.1 | 92.8 | 95.6 | χ2(1) = 0.97, P = 0.32 |

| Race, % | χ2(1) = 9.91, P = 0.002 | |||

| Anglo-American | 87.2 | 93.5 | 80.7 | |

| Black or African American | 3.7 | 0.7 | 6.7 | |

| Hispanic | 3.3 | 2.9 | 3.7 | |

| Other | 4.7 | 2.2 | 7.4 | |

| Missing | 1.1 | 0.7 | 1.5 | |

| Marital status, % | χ2(1) = 2.51, P = 0.11 | |||

| Married | 71.1 | 75.4 | 66.7 | |

| Not married | 28.9 | 25.6 | 33.3 | |

| Education, % | χ2(3) = 3.97, P = 0.27 | |||

| High school or less | 12.1 | 9.4 | 14.8 | |

| Vocational school/some college | 25.6 | 25.4 | 25.9 | |

| College | 39.6 | 38.4 | 40.7 | |

| Graduate/professional school | 21.2 | 25.4 | 17.0 | |

| Missing | 1.5 | 1.4 | 1.5 | |

| Household annual income, % | χ2(5) = 7.85, P = 0.17 | |||

| <10,000 | 2.6 | 2.2 | 3.0 | |

| 10,000–29,999 | 10.6 | 6.5 | 14.8 | |

| 30,000–49,999 | 12.5 | 14.5 | 10.4 | |

| 50,000–69,999 | 32.2 | 30.4 | 34.1 | |

| 70,000–100,000 | 10.3 | 13.0 | 7.4 | |

| >100,000 | 27.5 | 27.5 | 27.4 | |

| Missing | 4.4 | 5.8 | 3.0 | |

| Employment status, % | χ2(2) = 0.03, P = 0.99 | |||

| Full time | 47.3 | 49.3 | 45.2 | |

| Part time | 23.4 | 24.6 | 22.2 | |

| Not working | 23.4 | 19.6 | 27.4 | |

| Missing | 5.9 | 6.5 | 5.2 |

CBT, cognitive-behavioral therapy.

Per recommendations put forth by Feingold10 for estimating treatment effect sizes in growth-modeling analysis, effect sizes (reported as Cohen d) were calculated for the group × time interactions, interpretable as the effect of treatment group on the change over time of the outcome variable (ie, from baseline to posttreatment or from baseline to follow-up). Effect sizes are interpreted based on Cohen’s suggested ranges, with d = 0.2 indicating a small effect, d = 0.5 a medium effect, and d = 0.8 interpretable as a large effect.4 We also compared treatment acceptability and satisfaction ratings between treatment conditions using independent samples t tests.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive statistics

Participants included 273 adolescents with chronic pain, between the ages of 11 and 17 years (mean = 14.7, SD = 1.6). Demographic characteristics for adolescents and parents are presented in Table 1. Adolescent and parent participants were primarily female, Anglo-American, and middle class as indicated by annual household income between $50,000 and $100,000. Most parents had completed college or higher education. Adolescents presented with various pain conditions including musculoskeletal pain (41.8%), abdominal pain (11.4%), and headache (7.0%), with many youth having multiple pain conditions (39.9%). On average, before treatment, adolescents reported pain that was moderate to severe intensity (mean = 6.0, SD = 1.9).

3.2. Group equivalence on demographic and pretreatment variables

Participants in the 2 groups were equivalent with respect to age, sex, pain condition, and parent education (Table 1). Independent samples t tests indicated that participants in the 2 groups were also equivalent on pretreatment ratings of computer comfort as reported by adolescents, t(263) = 1.63, P = 0.10, and parents, t(272) = 0.50, P = 0.62. The 2 groups were significantly different, however, on adolescent and parent race. Adolescents and parents in the Internet CBT group were more likely to be Anglo-American when compared with adolescents and parents in the Internet education group, χ2(1) = 10.86, P = 0.001, χ2(1) = 9.91, P = 0.002, respectively. The 2 treatment groups did not show statistically significant differences on any other demographic characteristics or pretreatment outcome variables. Participants who dropped out of the study and those who completed the study did not demonstrate statistically significant differences on any demographic variables or pretreatment outcome variables (P values > 0.05).

3.3. Treatment expectancies

An independent samples t test indicated that there was no difference in treatment expectancies between the Internet CBT group and the Internet education group as reported by adolescents, t(265) = 1.22, P = 0.23, and parents, t(266) = 0.64, P = 0.52.

3.4. Treatment engagement

Most adolescents and parents in the 2 groups demonstrated high treatment engagement based on module completion. In the Internet CBT group, adolescents (SD = 1.8) and parents completed an average of 7 of 8 modules (SD = 1.9). Similarly, in the Internet education group, adolescents (SD = 1.4) and parents also completed an average of 7 of 8 modules (SD = 1.9). Parent-adolescent dyads in the Internet CBT group completed an average of 14 of 16 modules (SD = 3.8), with 67% of families completing all modules. Parent-adolescent dyads in the Internet education group completed an average of 15 of 16 modules (SD = 2.9), with 80% of families completing all modules.

3.5. Primary outcome analyses

Means and SDs for primary, secondary, and exploratory outcome variables before treatment, after treatment, and 6-month follow-up are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Unadjusted descriptive statistics on primary, secondary, and exploratory treatment outcomes by treatment condition.

| Variable | CBT (n = 134), mean (SD) |

Education (n = 135), mean (SD) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | T2 | T3 | T1 | T2 | T3 | |

| Activity limitations (CALI) | 7.42 (4.52) | 5.68 (4.38) | 5.46 (4.32) | 7.01 (4.56) | 5.65 (4.69) | 6.16 (5.04) |

| Pain intensity (NRS) | 6.23 (1.72) | 5.87 (2.05) | 5.85 (1.97) | 5.78 (1.94) | 5.59 (2.15) | 5.55 (2.02) |

| Adolescent emotional functioning (BAPQ) | ||||||

| Depressive symptoms | 11.31 (4.95) | 9.71 (5.10) | 9.55 (5.13) | 9.94 (4.80) | 9.32 (5.37) | 9.49 (5.58) |

| Pain-related anxiety | 13.79 (6.04) | 10.56 (5.91) | 10.35 (6.12) | 12.66 (5.28) | 10.85 (6.10) | 10.23 (5.45) |

| Sleep quality (ASWS) | 3.49 (0.80) | 3.75 (0.76) | 3.76 (0.80) | 3.63 (0.80) | 3.77 (0.84) | 3.76 (0.77) |

| Miscarried helping (HHI) | ||||||

| Adolescent report | 33.86 (9.86) | 31.41 (8.30) | 31.69 (9.26) | 33.52 (9.41) | 34.24 (9.10) | 34.13 (8.83) |

| Parent report | 32.99 (8.57) | 31.64 (9.04) | 31.52 (9.08) | 33.01 (9.48) | 33.38 (9.20) | 33.12 (9.10) |

| Parent responses to pain behaviors (ARCS) | ||||||

| Protective behaviors | 1.44 (0.56) | 1.05 (0.57) | 1.00 (0.58) | 1.41 (0.62) | 1.29 (0.60) | 1.17 (0.63) |

| Minimizing behaviors | 0.96 (0.51) | 0.95 (0.47) | 0.95 (0.49) | 0.99 (0.65) | 0.99 (0.68) | 0.97 (0.68) |

| Distract/monitor behaviors | 2.74 (0.56) | 2.46 (0.68) | 2.39 (0.71) | 2.69 (0.61) | 2.51 (0.63) | 2.47 (0.67) |

| Parent pain-related impact (BAPQ-PIQ) | ||||||

| Depressive symptoms | 12.26 (5.88) | 10.22 (5.96) | 9.47 (5.87) | 12.32 (6.55) | 11.15 (6.48) | 10.85 (6.25) |

| Anxiety symptoms | 8.58 (4.73) | 7.01 (4.69) | 6.37 (4.67) | 8.52 (5.49) | 7.35 (5.43) | 6.77 (5.13) |

| Pain catastrophizing | 8.60 (4.12) | 6.75 (3.92) | 6.56 (4.20) | 8.31 (4.06) | 7.20 (4.23) | 7.03 (4.29) |

| Self-blame | 11.26 (6.18) | 8.07 (6.49) | 7.43 (6.27) | 10.93 (5.89) | 8.86 (5.96) | 8.76 (6.08) |

| Partner relationships | 10.94 (4.73) | 10.62 (5.18) | 10.03 (5.56) | 10.89 (5.77) | 10.76 (6.05) | 10.96 (5.99) |

| Social functioning | 15.39 (4.65) | 14.05 (5.10) | 14.42 (3.90) | 15.65 (4.99) | 14.70 (5.83) | 15.11 (4.42) |

| Responses to pain | 23.16 (6.04) | 18.95 (6.44) | 19.73 (5.71) | 23.01 (6.15) | 20.95 (6.58) | 19.87 (5.90) |

| Role strain | 8.10 (5.23) | 7.43 (5.14) | 7.67 (5.49) | 8.09 (4.81) | 8.15 (5.50) | 7.90 (5.17) |

ARCS, Adult Responses to Children’s Symptoms; ASWS, Adolescent Sleep Wake Scale; BAPQ, Bath Adolescent Pain Questionnaire; BAPQ-PIQ, Bath Adolescent Pain Questionnaire-Parent Impact Questionnaire; CALI, Child Activity Limitations Interview; CBT, cognitive-behavioral therapy; NRS, numerical rating scale.

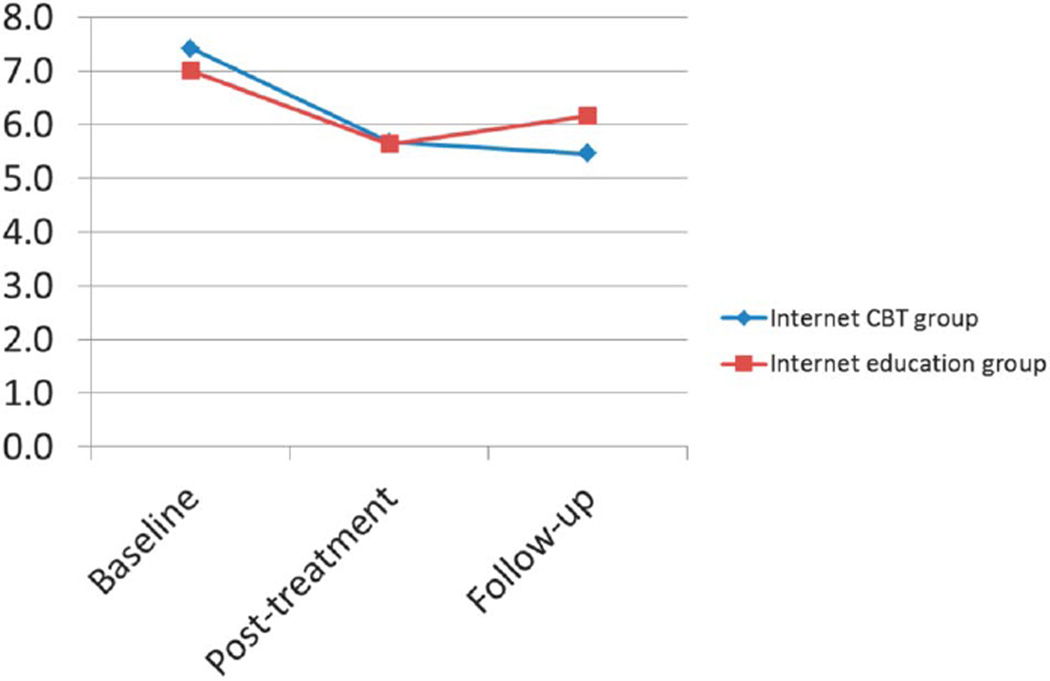

3.5.1. Activity limitations

The results partially supported our primary hypothesized effects: from baseline to 6-month follow-up, youth receiving Internet CBT achieved greater reductions in daily activity limitations than did the Internet education group, and this was a small, significant effect (b = −1.13, P = 0.03, d = −0.25). However, immediately after treatment, there was not a statistically significant difference between the Internet CBT group and the Internet education group on change in daily activity limitations from baseline (b = −0.43, P = 0.39). See Figure 3 for a graph showing change in daily activity limitations over time by group.

Figure 3.

Changes in activity limitations (primary outcome) over time by treatment condition.

3.6. Secondary outcome analyses

3.6.1. Pain intensity

In contrary to hypotheses, although pain reduced over time, there was no statistically significant difference in change in pain intensity between treatment groups at baseline to posttreatment (b = −0.28, P = 0.24) or baseline to follow-up (b = −0.30, P = 0.07).

3.6.2. Emotional functioning

As hypothesized, there were small effects of Internet CBT on adolescent emotional functioning at posttreatment. Specifically, small treatment effects were found for reductions in depressive symptoms in the Internet CBT group relative to the Internet education group from baseline to posttreatment (b = −0.59, P = 0.04, d = −0.09), but this was not maintained at follow-up (b = −0.93, P = 0.08).

Similarly, there was a small effect of treatment on decreases in pain-related anxiety symptoms. Adolescents receiving Internet CBT showed a significant reduction in pain-related anxiety relative to the Internet education group from baseline to posttreatment (b = −1.33, P = 0.04, d = −0.13), but this was not maintained at follow-up (b = −0.89, P = 0.17).

3.6.3. Sleep quality

Hypotheses about change in sleep quality were partially supported. Adolescents receiving Internet CBT achieved a significantly greater magnitude of improvement in sleep quality compared with the Internet education group from baseline to 6-month follow-up, and this is a small effect (b = 0.14, P = 0.04, d = 0.16). However, there was no difference in change in sleep quality between treatment groups at baseline to posttreatment (b = 0.13, P = 0.07).

3.6.4. Miscarried helping

Between-group differences on parent report of miscarried helping were not significant from baseline to posttreatment (b = −1.59, P = 0.08) or from baseline to follow-up (b = −1.52, P = 0.09). Small treatment effects were detected for adolescent report of miscarried helping where a significantly greater reduction in parent miscarried helping was reported by youth in the Internet CBT group than by youth in the Internet education group from baseline to posttreatment (b = −3.06, P = 0.002, d= −0.30) and from baseline to 6-month follow-up (b = −2.66, P = 0.007, d = −0.26).

3.6.5. Parent responses to pain behaviors

As hypothesized, there were significant, small to medium effects of treatment on reducing maladaptive parent behaviors. Parents in the Internet CBT group demonstrated a significantly greater reduction in protective behaviors than that of the Internet education group from baseline to posttreatment (b = −0.26, P < 0.001, d = −0.49) and from baseline to 6-month follow-up (b = −0.19, P = 0.001, d= −0.40).

There was no statistically significant treatment effect on parent-minimizing behaviors or parent distracting and monitoring behaviors from baseline to posttreatment (b = −0.02, P = 0.79; b = −0.09, P = 0.16), respectively. There was also no treatment effect on parent-minimizing behaviors from baseline to follow-up (b = 0.06, P = 0.93) or on parent distracting and monitoring responses from baseline to follow-up (b = −0.13, P = 0.06).

3.7. Treatment satisfaction and acceptability

Adolescents and parents in the Internet education group reported moderate satisfaction and acceptability for the intervention immediately after treatment (youth: mean = 29.9, SD = 5.0; parent: mean = 30.2, SD = 4.9) and at follow-up (youth, mean = 29.7, SD = 5.9; parent, mean = 29.6, SD = 6.0). Comparatively, as hypothesized, adolescents and parents in the Internet CBT group reported significantly higher satisfaction and acceptability for the intervention immediately after treatment (youth: mean = 32.2, SD = 4.7, t(253) = 3.84, P < 0.001; parent: mean = 33.0, SD = 4.5, t(254) = 4.89, P < 0.001) and at follow-up (youth: mean = 31.9, SD = 4.9, t(246) = 3.25, P = 0.001; parent: mean = 32.8, SD = 5.2, t(243) = 4.48, P < 0.001). Scores indicate that both treatments are acceptable to adolescents and parents (means >27).

Web program-specific preference ratings were also in the moderate range. After treatment, adolescents assigned to the CBT condition rated significantly higher preference for the appearance of the Web program (CBT: mean = 4.1, SD = 0.8 vs education: mean = 3.8, SD = 1.0, t(252) = 2.31, P = 0.02) and the travel theme (CBT: mean = 4.2, SD = 1.0 vs education: mean = 3.9, SD = 1.1, t(255) = 2.60, P = 0.01) and rated the overall usefulness as higher (CBT: mean = 4.1, SD = 0.8 vs education: mean = 3.8, SD = 1.0, t(253) = 2.13, P = 0.03) compared with adolescents in the education condition. Similarly, after treatment, parents assigned to the CBT condition also rated significantly higher preference for the appearance (CBT: mean = 4.4, SD = 0.7 vs education: mean = 4.1, SD = 0.8, t(251) = 3.89, P < 0.0001) and the travel theme (CBT: mean = 4.3, SD = 0.9 vs education: mean = 4.0, SD = 0.9, t(252) = 2.95, P = 0.003) and rated the overall usefulness as higher (CBT: mean = 4.5, SD = 0.7 vs education: mean = 4.0, SD = 0.9, t(245) = 4.46, P < 0.0001) than parents in the Education condition. Adolescents and parents rated ease of navigation on the Web program similar for both treatment conditions.

3.8. Exploratory outcome analyses

3.8.1. Parent pain-related impact

The parent impact measure (BAPQ-PIQ) was added to the protocol after the trial began and thus represents an exploratory outcome. Scores are available for 162 parents at baseline (Internet CBT [n = 80]; Internet education [n = 82]), 194 after treatment (Internet CBT n = 97; Internet education n = 97), and 221 at 6-month follow-up (Internet CBT [n = 113]; Internet education [n = 108]).

Treatment produced a number of positive changes in parent pain-related impact including reductions in parent anxiety and depressive symptoms, decreased maladaptive behavioral responses to pain, and reduced self-blame. Specifically, from baseline to 6-month follow-up, parents in the Internet CBT group demonstrated a significantly greater reduction in anxiety symptoms than did parents in the Internet education group (b = −1.37, P = 0.02, d = −0.39), and this is a small to medium effect. However, changes from baseline to posttreatment did not differ between groups (b = −0.86, P = 0.15). Similarly, treatment produced reductions in parent depressive symptoms. Parents in the Internet CBT group had a greater reduction in depressive symptoms compared with parents in the Internet education group from baseline to posttreatment, and this approached statistical significance (b = −1.44, P = 0.05, d = 0.27). This effect became stronger over time. From baseline to 6-month follow-up, parents in the Internet CBT group demonstrated a significantly greater reduction in depressive symptoms compared with parents in the Internet education group (b = −2.25, P = 0.002, d = 0.44), and this is a small to medium effect.

Parents in the Internet CBT group also had a greater improvement in behavioral responses to their adolescent’s pain from baseline to posttreatment, and this was a medium effect (b = −2.55, P = 0.001, d = −0.45), although this was not maintained at 6-month follow-up (b = −0.65, P = 0.40). Finally, parents in the Internet CBT group had a greater reduction in self-blame about their adolescent’s pain compared with parents in the Internet education group from baseline to posttreatment (b = −1.72, P = 0.03, d = 0.31) and baseline to 6-month follow-up (b = −2.24, P = 0.003, d = −0.34), and these were small to medium effects. There were no treatment effects detected from baseline to either additional assessment for parent pain catastrophizing, impairment in partner relationship, parent social functioning, and parent role strain.

3.9. Adverse events

Major life events and stressors (eg, parent death, serious illness) were reported by 4 participants during our collection of adverse events. However, these were not described or categorized as study-related adverse events.

Additionally, one adverse event was detected by an online coach through a response on a behavioral assignment in which a participant in the CBT condition reported having thoughts of self-harm. This event was not attributed to participation in study procedures.

4. Discussion

This is the first large multicenter RCT of Internet-delivered CBT for pediatric chronic pain and disability. A number of positive effects were found for primary, secondary, and exploratory outcomes. At 6-month follow-up, adolescents receiving Internet CBT experienced fewer activity limitations compared with adolescents receiving Internet education. On secondary outcomes, we found significant effects on reductions in adolescent depression and pain-specific anxiety symptoms and improvements in sleep quality and parent miscarried helping. Treatment satisfaction was higher in families receiving Internet CBT compared with Internet education. Last, Internet CBT led to reductions in parent depression, anxiety, self-blame about their adolescent’s pain, and in their maladaptive behavioral responses to their adolescent’s pain. Pain intensity decreased over time, but no treatment group effects were found for pain intensity. Treatment engagement was high across both treatment conditions with the majority of youth and parents completing all treatment modules. Although most treatment effects were small, the wide reach of Internet-delivered intervention increases the potential impact of the findings at a population level.

These findings extend our earlier research in which we demonstrated feasibility and preliminary efficacy of Web-MAP vs wait-list control in a small sample of youth with chronic pain.23,30 In this study, we used a more rigorous attention control RCT design with a large multicenter sample to conduct a definitive evaluation of the effectiveness of Web-MAP.

Office-based CBT is resource intensive, requiring 8 to 10 sessions to teach behavioral coping skills. There is a scarcity of trained providers, and most children with chronic pain will not receive CBT. In one community-based sample,33 the majority of youth had used medications for pain but only 2.8% received any psychological treatment. Even in clinical samples in pain clinics, average visits to a psychologist in last 6 months was only 2 visits,35 which suggests that even those who receive psychological care often do not complete a full course of treatment. In contrast, most families in this study completed the full treatment, consistent with evidence of the potential for remotely delivered psychological treatment to address these barriers.12 In a recent Cochrane review of remotely delivered therapy, 8 RCTs including 371 youth (headache, arthritis, and mixed pain) receiving treatment through the Internet, telephone, or CD-ROM were included. Small, beneficial effects were found for pain reduction but no effects were found for disability or depression. Results from our multicenter trial add to this evidence base for new findings on disability, sleep, and parent behaviors and emotional functioning.

Differences in study designs and samples may account for some of the contrasting findings between psychological treatment trials for pediatric chronic pain. Our study design was more rigorous than many previous evaluations of CBT, which have often used wait-list or usual care control conditions, short follow-up periods, and single-center recruitment. In our trial, the Internet education condition equalized attention, contact time, and mode of treatment delivery. In addition, it was credible to participants, as measured by high participation rates and satisfaction ratings. Using this design, we were able to blind participants to whether they received an active or control intervention, providing a rigorous test of whether the specific active interventions in the CBT arm were efficacious. Our 6-month follow-up provided data on durability of treatment effects. Enrollment of youth from 12 different pain centers across North America increases representativeness of the sample and addresses biases inherent in single-center recruitment. An additional strength was use of prospective daily measurement of pain intensity and activity limitations.

Our treatment effects, although modest, are similar to those found in published trials of face-to-face CBT for pediatric chronic pain. In a recent systematic review and meta-analysis of psychological therapies for the treatment of chronic pain in youth, small effects of psychological treatments were found on reductions in pain, disability, and depressive symptoms.11 However, an important difference to consider is the mode of treatment delivery, which is low cost and easily scalable.

Our sample was recruited from interdisciplinary pain clinics where youth had received initial evaluation. Referral to a tertiary pain clinic is typically reserved for pediatric patients who have severe symptoms and disability. Given our limited exclusion criteria and focus on real-world patients, our trial was closer to an effectiveness trial than a pure efficacy trial. This introduced heterogeneity in the sample that likely diminished our ability to detect treatment effects. However, it strengthens the generalizability of the study findings to typical patients presenting for treatment in pediatric chronic pain clinics. Although Internet access was an inclusion criterion of study participation, few families (less than 2%) did not have access. However, future studies will be needed, especially across a broader range of socioeconomic levels, to understand how to apply Internet interventions in lower resourced samples.

Another strength of the study is that we evaluated treatment effects on a range of outcome domains per recommendations of PedlMMPACT24 including pain, physical functioning, sleep, emotional functioning, treatment satisfaction, and parent emotional and behavioral functioning. To our knowledge, this is the first RCT of a psychological treatment for pediatric chronic pain to report on sleep outcomes. In a recent meta-analysis of psychological treatments for pediatric chronic pain,11 none of the 37 studies included sleep outcomes. Sleep problems are a frequently occurring comorbidity29 that contributes to pain-related dysfunction.27 Although we found significant beneficial effects of Internet-delivered CBT on change in sleep quality at 6-month follow-up, these results should be interpreted cautiously as the effect size is small and may not be clinically meaningful. Findings highlight the need for further data on sleep outcomes in future psychological treatment trials.

Results demonstrated that Internet-delivered CBT produced positive effects on parent outcomes. These findings extend a limited literature on parent interventions in families of children with chronic pain. In a Cochrane review on interventions for parents of youth with chronic medical conditions,5 there was no evidence for the effectiveness of CBT in improving parental mental health or behavioral outcomes. In contrast, we found positive effects on parent behavioral responses to child pain and improvements in parent emotional functioning.

Web-MAP2 contains greater content and treatment exposure (4 treatment hours) for parents than many previous trials of CBT for pediatric chronic pain,7 where parents on average receive none or brief treatment (eg, approximately 1 hour). Web-MAP2 provides parent training in multiple skills (operant strategies, communication, and modeling), and treatment exposure is equivalent for youth and parents (8 modules each). Although limited time may be available for parent intervention in clinic settings, remote treatment programs such as Web-MAP2 have the potential to involve multiple family members who may access skills training in the home. The fact that parents made numerous gains with Internet CBT is exciting and points to the potential value in offering this low-intensity treatment to all parents of youth with chronic pain. Future studies are needed to understand whether some families could achieve similar benefits when treatment is delivered only to parents or only to youth.

There are a number of future directions of our research. We are at present collecting follow-up data at 12 months to examine differences in health utilization by treatment condition and to examine mediators and moderators of long-term outcomes. These additional analyses will provide further understanding of the impact of Internet-delivered CBT and who benefits from this treatment approach. Because we did not alter standard care for this trial, some youth may have received CBT and other treatments, which could have attenuated our treatment effects. Indeed, our Internet CBT program may be most effective for the significant proportion of youth who do not have access to specialized pain care (eg, Ref. 32). Given the potential for widespread dissemination of Internet-delivered CBT, this program may be used in stepped care approaches to pain management to provide low-cost access to cognitive and behavioral skills training. We are also considering ways to enhance the clinical effectiveness of WebMAP such as stepping up the intensity of the online coaching and by applying additional interventions to address risk factors (eg, insomnia) for poor treatment response.

Our findings should be interpreted in light of several limitations. Although we screened youth for having chronic pain for at least 3 months, we did not collect data on the duration of the chronic pain condition. Our Internet CBT program contains human support (ie, online coach), which may increase accountability and therapeutic alliance but does reduce ease of dissemination. Future planned iterations of our Internet program are to increase automation and evaluate whether a fully automated approach is also effective. If we are able to identify who does and does not respond to Internet CBT, then strategies can be developed to address lack of engagement. Limited data are available at present to guide decisions about which psychological treatment might benefit which youth and families. Future studies could also directly compare Internet CBT with face-to-face CBT to better understand which families benefit from which mode of treatment delivery.

In conclusion, Internet interventions address barriers to access and could ultimately lead to wide dissemination of evidence-based psychological pain treatment for youth and their families.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the youth and families who participated in the study and also the collaborating pain centers including Cincinnati Children’s Hospital, Children’s Mercy Hospital & Clinics, Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, IWK Health Centre, Connecticut Children’s Medical Center, Children’s Hospital Boston, Stollery Children’s Hospital, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, The Hospital for Sick Children, Oregon Health & Science University, Nationwide Children’s Hospital, Ochsner Hospital for Children, Children’s Hospitals and Clinics of Minnesota, Mayo Clinic, and Seattle Children’s Hospital for their involvement in the research.

Research reported in this study was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01HD062538 (T.M.P. [principal investigator]). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Sponsorships or competing interests that may be relevant to content are disclosed at the end of this article.

Conflict of interest statement

None of the authors have any conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Bender JL, Radhakrishnan A, Diorio C, Englesakis M, Jadad AR. Canpain be managed through the Internet? A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. PAIN. 2011;152:1740–1750. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2011.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carey JC, Wade SL, Wolfe CR. Lessons learned: the effect of prior technology use on web-based interventions. Cyberpsychol Behav. 2008;11:188–195. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2007.0025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Claar RL, Guite JW, Kaczynski KJ, Logan DE. Factor structure of the adult responses to children’s symptoms: validation in children and adolescents with diverse chronic pain conditions. Clin J Pain. 2010;26:410–417. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e3181cf5706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eccleston C, Fisher E, Law E, Bartlett J, Palermo TM. Psychological interventions for parents of children and adolescents with chronic illness. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;4 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009660.pub3. CD009660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eccleston C, Jordan A, McCracken LM, Sleed M, Connell H, Clinch J. The Bath Adolescent Pain Questionnaire (BAPQ): development and preliminary psychometric evaluation of an instrument to assess the impact of chronic pain on adolescents. PAIN. 2005;118:263–270. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eccleston C, Palermo TM, Williams AC, Lewandowski Holley A, Morley S, Fisher E, Law E. Psychological therapies for the management of chronic and recurrent pain in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;5 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003968.pub4. CD003968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Essner B, Noel M, Myrvik M, Palermo T. Examination of the factor structure of the Adolescent Sleep-Wake Scale (ASWS) Behav Sleep Med. 2015;13:296–307. doi: 10.1080/15402002.2014.896253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fales JL, Essner BS, Harris MA, Palermo TM. When helping hurts: miscarried helping in families of youth with chronic pain. J Pediatr Psychol. 2014;39:427–437. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsu003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Feingold A. Effect sizes for growth-modeling analysis for controlled clinical trials in the same metric as for classical analysis. Psychol Methods. 2009;14:43–53. doi: 10.1037/a0014699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fisher E, Heathcote L, Palermo TM, Williams AC, Lau J, Eccleston C. Systematic review and meta-analysis of psychological therapies for children with chronic pain. J Pediatr Psychol. 2014;39:763–782. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsu008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fisher E, Law E, Palermo TM, Eccleston C. Psychological therapies (remotely delivered) for the management of chronic and recurrent pain in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;3 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011118.pub2. CD011118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Groenewald CB, Essner BS, Wright D, Fesinmeyer MD, Palermo TM. The economic costs of chronic pain among a cohort of treatment-seeking adolescents in the United States. J Pain. 2014;15:925–933. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2014.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harris MA, Antal H, Oelbaum R, Buckloh LM, White NH, Wysocki T. Good intentions goneawry: assessing parental “miscarried helping”indiabetes. Families Systems Health. 2008;26:393–403. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heapy AA, Higgins DM, Cervone D, Wandner L, Fenton BT, Kerns RD. A systematic review of technology-assisted self-management interventions for chronic pain: looking across treatment modalities. Clin J Pain. 2015;31:470–492. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0000000000000185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huguet A, Miro J. The severity of chronic pediatric pain: an epidemiological study. J Pain. 2008;9:226–236. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2007.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jordan A, Eccleston C, McCracken LM, Connell H, Clinch J. The Bath Adolescent Pain-Parental Impact Questionnaire (BAP-PIQ): development and preliminary psychometric evaluation of an instrument to assess the impact of parenting an adolescent with chronic pain. PAIN. 2008;137:478–487. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kashikar-Zuck S, Cunningham N, Sil S, Bromberg MH, Lynch-Jordan AM, Strotman D, Peugh J, Noll J, Ting TV, Powers SW, Lovell DJ, Arnold LM. Long-term outcomes of adolescents with juvenile-onset fibromyalgia in early adulthood. Pediatrics. 2014;133:e592–e600. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-2220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kazdin AE. Acceptability of alternative treatments for deviant child behavior. J Appl Behav Anal. 1980;13:259–273. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1980.13-259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kelley ML, Heffer R, Gresham F, Elliot S. Development of a modified treatment evaluation inventory. J Psychopathol Behav Assess. 1989;11:235–247. [Google Scholar]

- 21.King S, Chambers CT, Huguet A, MacNevin RC, McGrath PJ, Parker L, MacDonald AJ. The epidemiology of chronic pain in children and adolescents revisited: a systematic review. PAIN. 2011;152:2729–2738. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2011.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.LeBourgeois MK, Giannotti F, Cortesi F, Wolfson AR, Harsh J. The relationship between reported sleep quality and sleep hygiene in Italian and American adolescents. Pediatrics. 2005;115(1 suppl):257–265. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-0815H. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Long AC, Palermo TM. Brief report:web-based management of adolescent chronic pain: development and usability testing of an online family cognitive behavioral therapy program. J Pediatr Psychol. 2009;34:511–516. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsn082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McGrath PJ, Walco GA, Turk DC, Dworkin RH, Brown MT, Davidson K, Eccleston C, Finley GA, Goldschneider K, Haverkos L, Hertz SH, Ljungman G, Palermo T, Rappaport BA, Rhodes T, Schechter N, Scott J, Sethna N, Svensson OK, Stinson J, von Baeyer CL, Walker L, Weisman S, White RE, Zajicek A, Zeltzer L; PedIMMPACT. Core outcome domains and measures for pediatric acute and chronic/recurrent pain clinical trials: PedIMMPACT recommendations. J Pain. 2008;9:771–783. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2008.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Palermo TM, Chambers CT. Parent and family factors in pediatric chronic pain and disability: an integrative approach. PAIN. 2005;119:1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Palermo TM, Jamison RN. Innovative delivery of pain management interventions: current trends and future progress. Clin J Pain. 2015;31:467–469. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0000000000000204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Palermo TM, Law E, Churchill SS, Walker A. Longitudinal course and impact of insomnia symptoms in adolescents with and without chronic pain. J Pain. 2012;13:1099–1106. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2012.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Palermo TM, Law EF, Zhou C, Holley AL, Logan D, Tai G. Trajectories of change during a randomized controlled trial of internet-delivered psychological treatment for adolescent chronic pain: how does change in pain and function relate? PAIN. 2015;156:626–634. doi: 10.1097/01.j.pain.0000460355.17246.6c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Palermo TM, Wilson AC, Lewandowski AS, Toliver-Sokol M, Murray CB. Behavioral and psychosocial factors associated with insomnia in adolescents with chronic pain. PAIN. 2011;152:89–94. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.09.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Palermo TM, Wilson AC, Peters M, Lewandowski A, Somhegyi H. Randomized controlled trial of an Internet-delivered family cognitive-behavioral therapy intervention for children and adolescents with chronic pain. PAIN. 2009;146:205–213. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2009.07.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Palermo TM, Witherspoon D, Valenzuela D, Drotar D. Development and validation of the Child Activity Limitations Interview: a measure of pain-related functional impairment in school-age children and adolescents. PAIN. 2004;109:461–470. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Peng P, Stinson JN, Choiniere M, Dion D, Intrater H, Lefort S, Lynch M, Ong M, Rashiq S, Tkachuk G, Veillette Y STOPPAIN Investigators Group. Dedicated multidisciplinary pain management centres for children in Canada: the current status. Can J Anaesth. 2007;54:985–991. doi: 10.1007/BF03016632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Perquin CW, Hunfeld JA, Hazebroek-Kampschreur AA, van Suijlekom-Smit LW, Passchier J, Koes BW, van der Wouden JC. Insights in the use of health care services in chronic benign pain in childhood and adolescence. PAIN. 2001;94:205–213. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(01)00355-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shek DT, Ma CM. Longitudinal data analyses using linear mixed models in SPSS: concepts, procedures and illustrations. Scientific World Journal. 2011;11:42–76. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2011.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Toliver-Sokol M, Murray CB, Wilson AC, Lewandowski A, Palermo TM. Patterns and predictors of health service utilization in adolescents with pain: comparison between a community and a clinical pain sample. J Pain. 2011;12:747–755. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2010.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tsao JC, Meldrum M, Bursch B, Jacob MC, Kim SC, Zeltzer LK. Treatment expectations for CAM interventions in pediatric chronic pain patients and their parents. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2005;2:521–527. doi: 10.1093/ecam/neh132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Van Slyke DA, Walker LS. Mothers’ responses to children’s pain. Clin J Pain. 2006;22:387–391. doi: 10.1097/01.ajp.0000205257.80044.01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.von Baeyer CL. Numerical rating scale for self-report of pain intensity in children and adolescents: recent progress and further questions. Eur J Pain. 2009;13:1005–1007. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2009.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Walker LS, Dengler-Crish CM, Rippel S, Bruehl S. Functional abdominal pain in childhood and adolescence increases risk for chronic pain in adulthood. PAIN. 2010;150:568–572. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Walker LS, Levy RL, Whitehead WE. Validation of a measure of protective parent responses to children’s pain. Clin J Pain. 2006;22:712–716. doi: 10.1097/01.ajp.0000210916.18536.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]