Abstract

Central vein disease is defined as at least 50% narrowing up to total occlusion of central veins of the thorax including superior vena cava, brachiocephalic, subclavian, and internal jugular vein. Thrombosis due to intravascular leads occurs in approximately 30% to 45% of patients early or late after implantation of a pacemaker by transvenous access.

In this case, we report a male patient, 65-years old, hypertensive, type 2 diabetic, with atherosclerotic disease, coronary artery disease, underwent coronary artery bypass surgery in the past 10 years, having already experienced an acute myocardial infarction, bearer automatic implantable cardioverter defibrillator for 8 years after an episode of aborted sudden death due to ischemic cardiomyopathy, presenting left superior vena cava syndrome. The use of clopidogrel and rivaroxaban for over a year had no benefit on symptoms improvement.

After atrial and ventricular leads extraction, a new shock lead was positioned in the right ventricle using active fixation and a new atrial lead was positioned in the right atrium, passing inside of the stents. Two days after the procedure the patient was asymptomatic and was discharged.

Central vein disease is defined as at least 50% narrowing up to total occlusion of central veins of the thorax including superior vena cava, brachiocephalic, subclavian, and internal jugular vein.1 Obstruction can be caused by invasion or external compression of the superior vena cava by adjacent pathologic processes involving the lung, lymph nodes, and other mediastinal structures or by thrombosis within the superior vena cava.2 In the past, infectious lesions were common causes; however, nowadays malignancy and the use of intravascular devices and cardiac pacemakers have become the main causes.2,3 Thrombosis due to intravascular leads occurs in approximately 30% to 45% of patients early or late after implantation of a pacemaker by a transvenous access.4 Several patients may be asymptomatic because they develop efficient collateral circulation. The incidence of pacemaker-induced superior vena cava syndrome has been reported to be less than 0.1%.5 In the meantime, the superior vena cava syndrome associated with internal leads may be a benign condition, or a debilitating and sometimes intractable complication. Furthermore, there is no consensus on a standard care management.6

Angioplasty and stent placement have been established as a less invasive but equally effective alternative to open surgical treatment.7 Meanwhile, angioplasty is potentially associated with lead damage and dysfunction. The trapping and crushing of leads by a stent would be an insolvable situation if the device gets infected. A percutaneous approach consisting of lead removal, stent implantation, and reimplantation of leads has been described with good results over the short and medium term follow-up.8 Long-term efficacy of this approach is still unknown. A recent study reported that percutaneous stent implantation after lead removal followed by reimplantation of leads is a feasible alternative therapy for pacemaker-induced superior vena cava syndrome, although some cases may require repeat intervention.9

In this case, we report a male patient, 65-years old, hypertensive, type 2 diabetic, with atherosclerotic disease, coronary artery disease, underwent coronary artery bypass surgery in the past 10 years, having already experienced an acute myocardial infarction, bearer automatic implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) (Fig. 1) for 8 years after an episode of aborted sudden death due to ischemic cardiomyopathy, presenting left superior vena cava syndrome with the following symptoms: arms, neck, and face edema, besides development of swollen collateral veins on the chest wall, shortness of breath, and cough (the ethics committee composed by Paola Baars Gomes Moises, Luis Marcelo Rodrigues Paz, Humberto Cesar Tinoco e Jonny Shogo Takahashi, approved the execution of the case). Informed consent was signed by the patient.

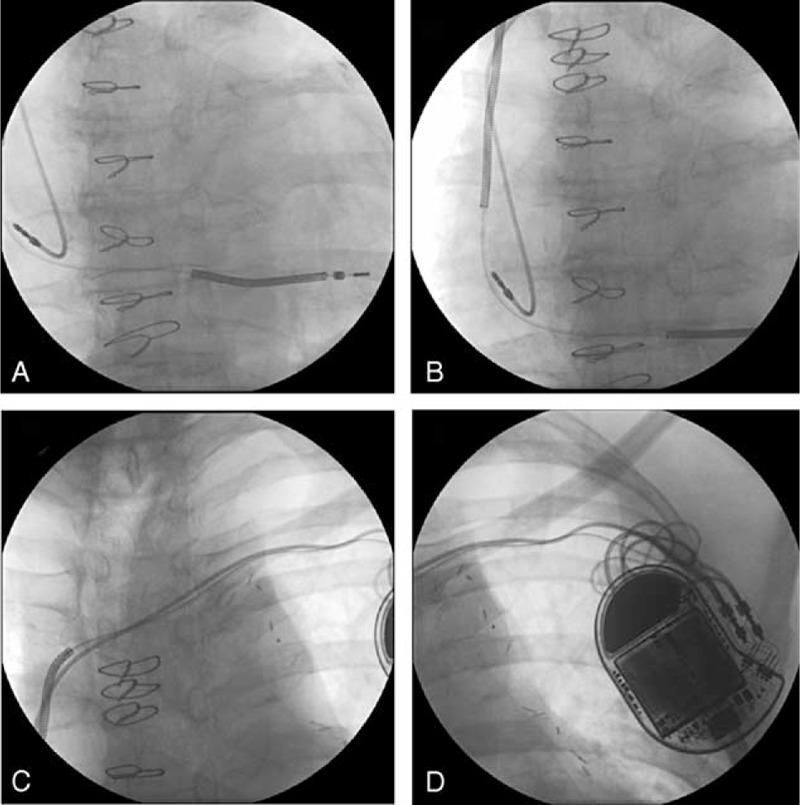

FIGURE 1.

Previous automatic implantable cardioverter defibrillator (A), (B), (C), and (D).

The use of clopidogrel and rivaroxaban for over a year had no benefit on symptoms improvement. The computed tomography angiography of the thoracic venous system showed a noted marked diameter reduction with irregular opacification in the brachiocephalic veins and distal half of the superior vena cava. This structure had normal caliber and was well opacified from the confluence with the azygos vein continuing along the jugular and subclavian veins. Exuberant collateral circulation was noted through the superficial veins in the chest wall, intercostal veins, paraspinal, and mediastinal. The strategy adopted was the extraction of the “double coil” shock lead positioned in the ventricle and the explant of the atrial lead, as well as the generator, to perform the patency of the route and the consequent improvement of symptoms. The leads were extracted after the introduction of the guides on both electrodes, dilation of the initial and middle portions of the left subclavian vein, clockwise and counterclockwise rotation of the leads, besides manual traction. The leads were extracted without any complications and the brachiocephalic vein where they were placed was partially obstructed, confirmed after infusion of non-iodinated contrast (Fig. 2). We opted first of lead extraction because the implantation of stents in this vein could fracture the electrodes.

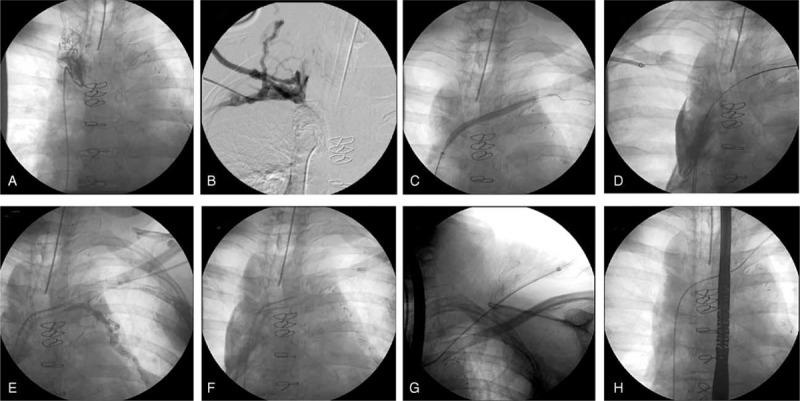

FIGURE 2.

Leads extraction without (A), (B), (C) and the left subclavian and brachiocephalic veins where they were placed has been partially unobstructed, confirmed after infusion of non-iodinated contrast (D).

The puncture of the right subclavian vein and the right femoral vein were performed, with an introduction of a short sheath 6F in each vein. Thereupon, hydrophilic wire guide (Aqualiner, Nipro Corporation, Japan) was introduced, as well as, an “over the wire” pig tail catheter. Venography with non-iodinated contrast through both accesses was performed. The superior vena cava had an unbridgeable thrombus (Fig. 3A and B) just above the right atrium, with only a tortuous and very narrow path between the superior vena cava and the brachiocephalic vein. The guidewire Aqualiner was replaced by another wire (road runner, Cook Medical, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil) due to this increased support and the femoral short sheath was replaced by 6F long sheath with 90 cm. A hydrophilic tip catheter (Slip-Cath Beacon Tip Hydrophilic Catheter, Cook Medical) was inserted to overcome the occlusion with success at this stage of the procedure (Fig. 3C–E). After several tries, this catheter was captured by a lassoer catheter (Multi-Snare, B. Braun Interventional Systems Inc., Rio de Janeiro, Brazil) inserted into the brachiocephalic vein through the left subclavian vein puncture (Fig. 3F). The guide wire was replaced by a fixed core wire guide (Fig. 3G and H) (Amplatz, Cook Medical) and angioplasty was performed with noncompliant balloon catheter, thus requiring the implantation of 2 self-expanding stents 28 mm × 60 mm (sinus-XL Stent, Optimed, Medizinische Instrumente GmbH, Ettlingen, Germany) in the left subclavian vein, brachiocephalic trunk, and the superior vena cava followed by dilation with balloon catheter of 26 mm × 4 cm (Zelos PTA – Balloon Catheter, Optimed, Medizinische Instrumente GmbH, Ettlingen, Germany). A venography ensured the access to ICD implantation (Fig. 4A–F).

FIGURE 3.

Angiography of the venous system showing the superior vena cava with an unbridgeable thrombus just above the right atrium (A) and (B). A tip hydrophilic catheter was inserted to overcome the occlusion, with success at this stage of the procedure (C), (D), and (E). The tip hydrophilic catheter was captured by a lassoer catheter inserted into the brachiocephalic vein through the left subclavian vein puncture (F). The guide wire was replaced by a fixed core wire guide (G) and (H).

FIGURE 4.

Angioplasty with noncompliant balloon catheter (A) and (B). Implantation of 2 self-expanding stents (C), in the left subclavian vein, brachiocephalic trunk, and the superior vena cava, followed by dilation with balloon catheter (D), and venography (E) and (F), ensuring the access to ICD implantation. A new “mono coil” shock lead was positioned in the apex of the right ventricle (G) and a new atrial lead was positioned in the right atrium (H), passing inside of the stents.

A new “mono coil” shock lead was positioned in the apex of the right ventricle using active fixation and a new atrial lead was positioned in the right atrium, passing inside of the stents. Both were fixed in the pectoral muscles and connected to the ICD generator (Fortify ICD DR, St. Jude Medical, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil) (Fig. 4G and H). In the day after the procedure, the symptoms were no longer present and the patient was discharged on the second day after the procedure. Until the present time of follow-up (3 months) the patient remained asymptomatic. The patient was discharged using aspirin, clopidogrel, and rivaroxaban.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Mr. Sérgio Oliveira for their technical support.

Footnotes

The authors have no funding and conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Modabber M, Kundu S. Central venous disease in hemodialysis patients: an update. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2013; 36:898–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilson LD, Detterbeck FC, Yahalom J. Superior vena cava syndrome with malignant causes. N Engl J Med 2007; 356:1862–1869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rice TW, Rodriguez RM, Light RW. The superior vena cava syndrome: clinical characteristics and evolving etiology. Medicine 2006; 85:37–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spittell PC, Hayes DL. Venous complications after insertion of atransvenous pacemaker. Mayo Clin Proc 1992; 67:258–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mazzetti H, Dussaut A, Tentori C, et al. Superiorvena cava occlusion and/or syndrome related to pacemaker leads. Am Heart J 1993; 125:831–837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Riley RF, Petersen SE, Ferguson JD, et al. Managing superiorvena cava syndrome as a complication of pacemaker implantation: a pooled analysis of clinical practice. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2010; 33:420–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rizvi AZ, Kalra M, Bjarnason H, et al. Benign superior vena cava syndrome: stenting is now the first lineof treatment. J Vasc Surg 2008; 47:372–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chan AW, Bhatt DL, Wilkoff BL, et al. Percutaneous treatment for pacemaker-associatedsuperior vena cava syndrome. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2002; 25:1628–1633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fu HX, Huang XM, Zhong L, et al. Outcome and management of pacemaker-induced superior vena cava syndrome. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2014; 37:1470–1476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]