Abstract

Objective

The purpose of this study was to identify trends of tobacco use, among all students and current tobacco users, in a nationally representative sample of high school students from 1999 to 2013.

Methods

Trends in individual and concurrent use of cigarettes, cigars, and smokeless tobacco (SLT) products were tested using 8 repeated cross-sections of the YRBS between 1999 and 2013. Tests for effect modification of race/ethnicity and sex were conducted for each trend.

Results

Among all students, there were significant non-linear changes detected for the concurrent use of all 3 products, and the dual use of cigarettes and cigars. Girls significantly increased their use of SLT. Among users, significant changes were detected for each individual product and all combinations. Female users significantly increased their concurrent use of cigarettes and cigars and concurrent use of cigarettes and SLT. Male users significantly decreased their use of cigarettes and cigars.

Conclusion

While the decrease in the youth prevalence of cigarette use is a public health success, there is concern about the increase in non-cigarette products, among tobacco users. These changes further drive increases in the concurrent use of tobacco products, adding to the potential health burden.

Keywords: multiple product use, adolescents

Introduction

Tobacco use is the number one cause of premature death worldwide. Tobacco use primarily begins in adolescence and young adulthood; almost 90% of adult daily smokers report trying their first cigarette prior to age 18, and 99% by age 26.1 Tobacco use in adolescence has been linked to several immediate health consequences, including early risk factors for heart disease, decreased lung function, and increased depressive symptoms; however, there is little information about how the use of more than one tobacco product may exacerbate the risk of these health consequences.1-4 This paper explores the use of multiple tobacco products among youth, and why such use may be of importance in future preventive efforts.

Cigarettes, cigars, and smokeless tobacco use are the 3 tobacco products, among youth, with long-term nationally representative data available. According to the national Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS) the prevalence of self-reported current (i.e., past 30 day) cigarette smoking among high school students peaked in 1999 at 35%, and has decreased to 15.7% in 2013.5 In 2013, the national YRBS estimated 12.6% of high school students smoked cigars, cigarillos, or little cigars, down from 17.7% in 1999.5 Lastly, 8.8% of high school students used smokeless tobacco in 2013, which included chew, snuff, and dip, down from 11.4% in 1999.5 Prevalence on other tobacco products are not available in the YRBS.

There are sex and racial/ethnic differences in the use of these 3 products. Boys are significantly more likely than girls to use cigars and smokeless tobacco products, but not cigarettes.5 Non-Hispanic White students are more likely to use cigarettes than non-Hispanic Blacks and Hispanic students. Non-Hispanic White students are significantly more likely to use smokeless tobacco products than either non-Hispanic Black or Hispanic students. Hispanic students are more likely to report using smokeless tobacco than non-Hispanic Black students.5 Among cigar users, there are no significant differences between the 3 racial/ethnic groups, according to the latest survey data.5

Overall, the prevalence of use of each of these tobacco products has decreased since the late 1990s. Little information is available on prevalence and trends of multiple-tobacco product use over time, however, especially among youth who are using at least one product (i.e., tobacco users).6,7 The 2012 Surgeon General's Report on tobacco and health showed that among male high school tobacco users, 55% reported using more than one tobacco product, according to the 2009 YRBS data.1 Other than this report, there are a handful of studies that have examined multiple-use of tobacco products.6-13 Most of these studies did not include more than 2 tobacco products,6-10 and even fewer examined trends in multiple product use over time.6,7,10 None have examined trends over an extended time period, from 1999-2013. Additionally, these studies have all used National Youth Tobacco Survey (NYTS) data, which were not collected consistently in the early 2000s. Further, the products surveyed in the NYTS have changed. The YRBS survey data have consistently been collected on 3 tobacco products since 1997.

The use of multiple tobacco products does not decrease and may increase the health risks associated with single tobacco product use; serum levels of cotinine, for example, are similar for dual users of smokeless tobacco and cigarettes as people who smoke daily.13 Use of smokeless tobacco products is marketed as a way to obtain needed nicotine in smoke-free environments.14,15 Importantly, with the increasing diversity of tobacco products offered by the tobacco industry, including e-cigarettes, snus, dissolvables and hookah, the use of more than one tobacco product may pose increasing risks for young people.

It is important to study multiple tobacco product use among people who are already using at least one tobacco product. These students are a particularly vulnerable population and are at higher risk for other risky behaviors, including the use of other tobacco products.1,9,16 Further, there may be underlying genetic factors which put these students at risk.17 Students who use one tobacco product are potentially diversifying their tobacco product use to maintain levels of nicotine. This is concerning, given the current diversification of tobacco products, and recent data that indicate that ever use of e-cigarettes by high school students has more than tripled between 2011 and 2014.18 New data from the Monitoring the Future study and the 2014 NYTS show that more adolescents have used e-cigarettes in the past 30 days than conventional cigarettes.18-20 Thus, the study of multiple tobacco product use is timely, given the increased options available to young people, the potential for addiction from any of these products, and the potential long-term consequences that might come from the use of multiple tobacco products.

The purposes of this paper are to determine the trends of multiple and individual tobacco product use over time, among all students and current tobacco users, and to examine socio-demographic differences in these trends. This is the first paper to look at trends of multiple tobacco product use, among tobacco users, in a nationally representative sample between 1999 and 2013.

Methods

Study Design

Trends in tobacco use were analyzed using nationally representative data from the national Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS). The YRBS is a biennial survey conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), which is administered to high school students, grades 9-12, in public and private schools. The purpose of analyzing these repeated cross-sectional surveys was to learn more about the prevalence of multiple tobacco use behaviors that lead to the primary causes of premature morbidity and mortality later in life, and problem behaviors among teenagers.21 The first national YRBS was conducted in 1991, and it has been revised over the years, yet the tobacco-related questions have remained the same over time. Questions regarding cigarette use were first asked in 1991, smokeless tobacco in 1995, and cigar use was added in 1997. Each survey is anonymous and administered by staff in the school. The data are all self-reported.

Methodology of the YRBS has been described previously.21 In order to obtain a nationally representative sample, the national YRBS uses a 3-stage cluster design.21 The first stage includes categorizing the primary sampling units (PSU) generated by the Quality Education Data. PSUs are categorized by the metropolitan status, percent of Black and Hispanic students, urbanization, and other demographic factors. The second stage selects schools with any of the grades 9-12 from the PSUs, identified in stage 1. Finally, the last stage picks one to 2 classrooms from each grade in each of the selected schools. Both Black and Hispanic students are oversampled, and the data are weighted to be nationally representative.21 The questions in the national YRBS have been analyzed in terms of reliability. All of the questions used in this study have at least moderate test-retest reliability (kappa value > .41), with most having substantial reliability (kappa value > .61).22

Repeated, cross-sectional data from 8 national YRBS surveys conducted between 1999 and 2013 were used for the current study. While all 3 tobacco products were surveyed in 1997, the analyses for the current study begin in 1999 since this is the first survey after the Master Settlement Agreement, as well as the first survey after the peak prevalence of youth tobacco use. Thus, using 1999 as the first time point allowed us to examine the use of tobacco products after the implementation of major changes in tobacco marketing to young people.1 Between 1999 and 2013, the overall response rate varied between 67% and 71%; the number of participating schools varied between 144 and 159; and the number of usable questionnaires ranged from 13,601 to 16,460.23

Measures

The primary tobacco variables related to self-reported use of cigarettes (smoked cigarettes ≥1 day during the past 30 days); cigars, little cigars, and cigarillos (smoked cigars ≥ 1 day during the past 30 days); and smokeless tobacco (used smokeless tobacco ≥1 day during the past 30 days). Socio-demographic variables of interest include race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic White; Hispanic; and non-Hispanic Black) and sex (boy; girl).

Analyses

The research questions addressed by these analyses were: 1. Was there a change in the reported use of individual or multiple tobacco products over time, from 1999 to 2013, among all students and among tobacco users?; and 2. Did any of these trends vary by sex or race/ethnicity? To determine whether there has been a change in use of individual or multiple products over time, the percent of adolescents who reported using each product and specific combinations of tobacco products were plotted over time so that trends could be identified. These analyses were also stratified by sex and race/ethnicity to compare trends, after testing for effect modification. Four possible combinations of multiple tobacco product use were examined: all 3 tobacco products (cigarettes, cigars, and smokeless), cigars and cigarettes, cigarettes and smokeless tobacco, and cigars and smokeless tobacco. Analyses were first conducted on all students; then, all analyses were conducted on a subset of students who responded that they currently used at least one tobacco product in order to examine trends in concurrent tobacco use in this high-risk population.

All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.3 (Cary, N.C.). Current use of each tobacco product was defined as reported use of the product at least one day in the past 30 days, as is standard in the youth tobacco literature.1 Racial/ethnic data were analyzed for non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, and Hispanic students, as there were sufficient numbers of these subgroups in the sample to provide reliable estimates. All data were weighted in the current analyses using available survey weights to ensure the estimates are nationally representative.

Trend analyses were conducted for individual tobacco products and all 4 combinations of multiple-tobacco product use (cigarettes, cigars, and smokeless tobacco; cigarettes and cigars; cigarettes and smokeless tobacco; and cigars and smokeless tobacco). Trends were tested using logistic regression analyses. These analyses assessed linear, quadratic, and cubic trends for each individual product and each combination of product, among tobacco users. Quadratic and cubic trends would suggest significant non-linear changes over time, while linear trends test for significant linear increases or decreases over time.

Differences by sex and race/ethnicity were examined by testing for effect modification. Interaction terms of time and sex or race/ethnicity were added to the regression analysis. If effect modification was determined to be present, then stratified analyses were conducted to test for trends within subsets.

Results

Multiple Tobacco Product Use, Among All Students

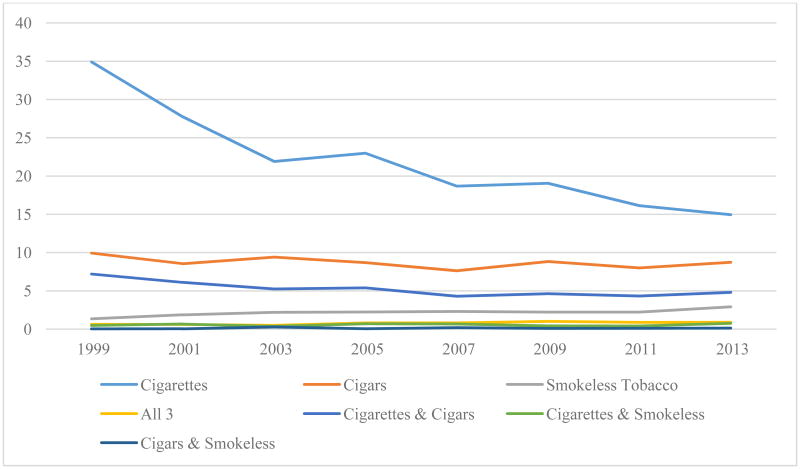

A summary of the trends and effect modification outcomes for each combination of multiple tobacco products, among all students, is shown in Table 1. The prevalence of each individual tobacco product and combination of products, by sex, are shown in Figures 1 and 2. A significant cubic trend occurred between 1999 and 2013 for the prevalence of all 3 tobacco products (p = .01). Between 1999 and 2003 the prevalence decreased from 3.2% to 2.2%, increased to 3.3% by 2009, and then decreased to 2.5% in 2013. The concurrent use of cigarettes and cigars was represented by a quadratic trend (p<.01); between 1999 and 2009 the prevalence decreased from 9.0% to 4.6%, there was a slight increase to 4.8% in 2011, and the prevalence in 2013 was 4.1%. The prevalence of cigarettes and smokeless tobacco did not significantly change between 1999 and 2013 (p = .30). The concurrent use of cigars and smokeless tobacco did not significantly change between 1999 and 2013 (p = .17). However, race/ethnicity was an effect modifier for the use of cigars and smokeless tobacco. There was a significant increase among non-Hispanic White students between 1999 and 2013 (p = .02), but no significant changes among non-Hispanic Black students (p = .12) and Hispanic students (p = .12). For all other trends, neither sex nor race/ethnicity were effect modifiers.

Table 1. Summary of Trend Analyses and Effect Modification, Multiple Tobacco Product Use.

| All Students | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Product(s) | Trend | Estimate | Standard Error | Wald Chi-Square | Pr > ChiSq |

| All 3 Tobacco products | Cubic | -0.01 | 0.00 | 5.98 | .01 |

| Cigarettes and Cigars | Quadratic | 0.02 | 0.01 | 8.85 | <.001 |

| Cigarettes and Smokeless Tobacco | Linear | -0.04 | 0.04 | 1.08 | .30 |

| Cigars and Smokeless Tobacco | Linear | 0.04 | 0.03 | 1.91 | .17 |

| Non-Hispanic White | Linear | 0.08 | 0.03 | 5.07 | .02 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | Linear | 0.17 | 0.11 | 2.40 | .12 |

| Hispanic | Linear | -0.18 | 0.12 | 2.44 | .12 |

| Current Tobacco Users | |||||

| Product(s) | Trend | Estimate | Standard Error | Wald Chi-Square | Pr>ChiSq |

| All 3 | Cubic | -0.01 | 0.00 | 3.86 | .05 |

| Cigarettes & Cigars | Linear | -0.02 | 0.01 | 2.22 | .14 |

| Males | Linear | -0.06 | 0.02 | 16.57 | <.001 |

| Females | Linear | 0.05 | 0.02 | 8.33 | <.001 |

| Cigarettes & Smokeless Tobacco | Linear | 0.05 | 0.03 | 1.71 | .19 |

| Males | Linear | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.25 | .62 |

| Females | Linear | 0.12 | 0.05 | 5.55 | .02 |

| Cigars & Smokeless Tobacco | Linear | 0.13 | 0.03 | 17.50 | <.001 |

Figure 1. Female Tobacco Product Use, All Students, 1999-2013.

Figure 2. Male Tobacco Product Use, All Students, 1999-2013.

Multiple Tobacco Product, Among Current Tobacco Users

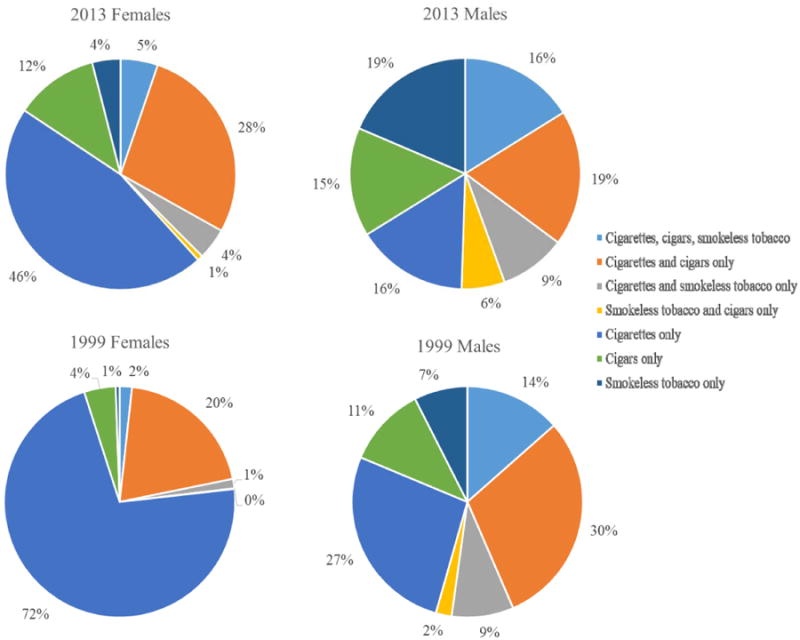

A summary of the trend analyses and effect modification tests, among current tobacco users, is shown in Table 1. There was a significant cubic trend between 1999 and 2013 for the prevalence of the use of all 3 tobacco products (p = .05). Between 1999 and 2009 the prevalence increased from 7.9% to 13.4%, then decreased to 11.8% in 2013. The prevalence of the concurrent use of cigars and smokeless tobacco significantly increased between 1999 and 2013 from 1.2% to 3.9% (p < .001). For these 2 trends, neither sex nor race/ethnicity were effect modifiers.

However, sex was identified as an effect modifier, but not race/ethnicity, for the concurrent use of cigarettes and cigars and the concurrent use of cigarettes and smokeless tobacco. Among male student users, concurrent use of cigarettes and cigars significantly decreased between 1999 and 2013 (p < .001) from 29.5% to 19.0%; however, the prevalence of cigarette and cigar use significantly increased among female high school student users (p < .001) from 19.9% in 1999 to 27.9% in 2013. There was no change in the prevalence of the dual use of cigarette and smokeless tobacco among male student users between 1999 and 2013 (p = .62), yet female student users'concurrent use of cigarettes and smokeless tobacco increased between 1999 and 2013 (p = .02) from 1.3% in 1999 to 4.4% in 2013.

Between 1999 and 2013 female tobacco users diversified their usage of tobacco products and combination of tobacco products when compared to male tobacco users, as shown in Figure 3. In 1999, more than three-quarters of female students, who currently used tobacco, used only one tobacco product (cigarettes, cigars, or smokeless tobacco), but in 2013 this decreased to less than two-thirds. Specifically, 72% of tobacco use was only cigarettes in 1999, among female tobacco users, but by 2013 only 46% of tobacco use was solely cigarettes. In 1999, 27% of male tobacco users used cigarettes only; this reduced further to 16% by 2013. In addition, in 2013, 38% of female tobacco users were using more than one tobacco product. This was true for 50% of the male tobacco users. Chi-square tests indicate there are significant changes between 1999 and 2013 for both male and female tobacco users (p < .001) in their use of more than one tobacco product.

Figure 3. Male and Female Multiple Tobacco Product Use, Among Tobacco Users 1999 v. 2013, p < 0.001.

Use of Individual Tobacco Products 1999-2013, All Students

In order to explain the trends in multiple tobacco product use, trends of individual tobacco products were examined; a summary of these trends is shown in Table 2. There has been a significant cubic trend in the prevalence of cigarette use between 1999 and 2013 (p = .01), but neither sex nor race/ethnicity were an effect modifier. Cigar use has significantly decreased from 15.92% in 1999 to 11.37% in 2013 (p < .001). Sex was identified as an effect modifier; boys significantly decreased the prevalence of cigar use (p < .001), but the prevalence of cigar use among girls did not significantly change between 1999 and 2013 (p = .14). Sex and race/ethnicity were identified as effect modifiers for smokeless tobacco use. Smokeless tobacco use did not significantly change among boys (p = .76), but there was a significant increase in smokeless tobacco use among girls (p = .01). There was no significant changes in the prevalence of smokeless tobacco use among non-Hispanic Whites (p = .32) and Hispanic students (p = .67), yet there was significant increase among non-Hispanic Black students (p = .01).

Table 2. Summary of Trend Analyses and Effect Modification, Individual Tobacco Products.

| All Students | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Product(s) | Trend | Estimate | Standard Error | Wald Chi-Square | Pr>ChiSq |

| Cigarettes | Cubic | -0.01 | 0.00 | 6.94 | .01 |

| Cigars | Linear | -0.05 | 0.01 | 26.85 | <.001 |

| Males | Linear | -0.07 | 0.01 | 42.61 | <.001 |

| Females | Linear | -0.02 | 0.01 | 2.18 | .14 |

| Smokeless Tobacco | Linear | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.85 | .36 |

| Males | Linear | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.09 | .76 |

| Females | Linear | 0.07 | 0.03 | 7.32 | .01 |

| Non-Hispanic White | Linear | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.99 | .32 |

| Non-Hispanic Blacks | Linear | 0.09 | 0.04 | 6.34 | .01 |

| Hispanic | Linear | -0.02 | 0.04 | 0.19 | .67 |

| Current Tobacco Users | |||||

| Product(s) | Trend | Estimate | Standard Error | Wald Chi-Square | Pr>ChiSq |

| Cigarettes | Linear | -0.13 | 0.01 | 98.89 | <.001 |

| Males | Linear | -0.11 | 0.01 | 61.58 | <.001 |

| Females | Linear | -0.18 | 0.03 | 44.61 | <.001 |

| Cigars | Linear | 0.05 | 0.01 | 14.88 | <.001 |

| Males | Linear | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.02 | .89 |

| Females | Linear | 0.10 | 0.02 | 31.90 | <.001 |

| Smokeless Tobacco | Linear | 0.11 | 0.02 | 35.01 | <.001 |

| Males | Linear | 0.10 | 0.02 | 18.74 | <.001 |

| Females | Linear | 0.17 | 0.02 | 50.27 | <.001 |

Use of Individual Tobacco Products 1999-2013, Current Tobacco Users

Among high school students who currently used tobacco products, the trends are not consistent with the entire population (all students) discussed above (see Table 2), although cigarette use did decrease from 86% in 1999 to 70% in 2013 (p < .001). However, the prevalence of cigar use (p < .001), and smokeless tobacco use (p < .001) increased significantly in this time period. For overall cigar use, the prevalence increased from 44% in 1999 to 52% in 2013. For smokeless tobacco use, the prevalence increased from 19% in 1999 to 36% in 2013. Tests for effect modification indicated that sex was an effect modifier for each individual product, but race/ethnicity was not. Among high school student tobacco users, the prevalence of cigarette use decreased for both boys (p < .001) and girls (p < .001); however, the rate at which cigarette use decreased among female tobacco users was nearly twice of that of male tobacco users. Between 1999 and 2013 girl cigar use increased (p < .001), yet there was no change in the prevalence of cigar use among high school male tobacco users (p = .89). Smokeless tobacco use increased in both male (p < .001) and female (p < .001) tobacco users; however, the increased rate at which girls reported smokeless tobacco use was greater than that of boys.

Discussion

Many studies have focused on the decline in individual tobacco product use.1,24-26 The analyses in this study show that among all students there have been declines in cigarette use and cigar use, but that among girls smokeless tobacco use has increased since 1999. Additionally, when looking at the entire population of students, there has been an increase in the concurrent use of cigarettes and cigars, and among non-Hispanic White students there has been an increase in the concurrent use of cigars and smokeless tobacco. Thus, while overall tobacco use has decreased, there are some tobacco products among some sub-groups that have shown an increase at the population level.

No other studies have examined the trends of multiple tobacco products as well as the use of individual products, among current tobacco users. Students who use at least one tobacco product are at risk for other health-compromising behaviors, which may include the use of other tobacco products.16,27,28 Additionally, students who use more than one tobacco product may have underlying genetic factors, which may put them at greater risk for addiction.17 The subset of analyses in this study, which were limited to current tobacco users, found significant increases in individual use of both cigars and smokeless tobacco. Further, there were significant increases in the concurrent use of cigarettes and cigars as well as the dual use of cigarettes and smokeless tobacco among current female tobacco users. This is the first study to show these important changes over time, among tobacco users, and particularly among female users.

Few studies have been published on multiple tobacco product use.6-13 All of these studies were cross-sectional, and 5 use nationally representative data.6,7,9,10,13 Four of these studies sought to determine the association or examine the relationship between cigarette smoking and use of other tobacco products.8-10,13 Five of the studies included more than 2 tobacco products and one study examined trends over time of these products.6-10 The 2012 Surgeon General's Report on tobacco and health and others have noted that the use of more than one tobacco product is common among users of any tobacco product.6-13 More than 50% of high school boys who used tobacco used more than one tobacco product.1 The most common combination was cigarettes and cigars, as in this study.1

Two studies have examined trends in multiple tobacco product use, with similar results to this study.6,7 Arrazola and colleagues used National Youth Tobacco Survey (NYTS) data from 2000 to 2012 to assess trends of tobacco use, including using more than one tobacco product.6 Arrazola et al. found significant linear downward trends for the combination of cigarettes and cigars and significant non-linear trends for cigarette use.6 Additionally, significant linear downward trends were detected among the current use of any tobacco product; use of one tobacco product; use of more than one tobacco product; use of 2 tobacco products; and cigarettes, cigars, and at least one other tobacco product.6 One large difference between the Arrazola et al. study and this study is that the current study included a subset analysis, which limited analyses to persons reporting using at least one tobacco product, but the Arrazola et al. study only included all students in their analyses. Arrazola et al. used NYTS data, while this study uses data from the YRBS. The current study shows very convincing data on the increase in smokeless tobacco and cigar use among high school tobacco users, and extends the data to 2013, highlighting the important increases in use among female users. These findings, of course, were not captured in Arrazola's study, given their design.

Nasim and colleagues also examined the trends of multiple tobacco product use (smokeless tobacco, cigars, bidis, and clove cigarettes) from 1999-2009 among light, moderate, and heavy smokers using National Youth Tobacco Survey (NYTS) data.7 Nasim et al. found that across all groups of smokers, the prevalence of smokeless tobacco increased in relation to smoking.7 However, Nasim et al. only looked at cigarette use with one other product; they did not look at the combinations of cigars and smokeless tobacco, and cigarettes, cigars, smokeless tobacco.7

Thus the current study adds to these prior studies by examining a longer time frame (1999-2013) and carefully analyzing the changes in use of multiple tobacco products among all students and among high school tobacco users. This is the first study to examine the changes in multiple tobacco product use among high school students who use at least one tobacco product. These findings are important given the increase in diversity of new and emerging tobacco products, such as e-cigarettes, snus, dissolvables, and hookah, which may be attractive to this age group, and may provide a pathway for increasingly diverse use of multiple tobacco/nicotine products, thus maintaining tobacco use and nicotine addiction. Also notable is the increase in smokeless tobacco and cigar use among girls, more than boys, where clearly more research is needed to address why these significant changes have occurred.

Results of this study indicate that there are key differences in trends over time between boys and girls. Because this study included additional analyses on students who are current tobacco users, prevention and cessation programs should be developed or implemented that are appropriate for girls and/or boys. Additionally, these programs should focus on multiple product use in order to prevent students from quitting one product and switching to another.

Strengths and Limitations

This is the first study to use the YRBS data to examine trends in multiple tobacco product use, among all students and among high school tobacco users. The data from the YRBS are nationally representative and are from a widely used surveillance system. Additionally, the measures of tobacco use behaviors are standard in the tobacco literature, with acceptable reliability. However, this study is not without limitations. The data are from repeated cross-sections, as opposed to a cohort, which limit casual implications and some analytic capabilities. Further, these data are from self-reported measures. There are no data, in the YRBS datasets, on emerging tobacco products (eg e-cigarettes, hookah, etc.), which may also be increasing among youth.19 The 2015 YRBS survey will ask questions on current and ever e-cigarette use, and should be incorporated into future analyses. Future studies should consider over-sampling tobacco users because this will provide more robust numbers for subset analyses where there was a lower overall prevalence of use.

Implications for Tobacco Regulatory Science

Given the diversity in tobacco products currently available to high school students, and with new and emerging products, there are important implications from this study regarding policy and practice. Currently, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has regulatory authority over cigarettes, roll-your-own cigarettes, and smokeless tobacco; regulation does not extend to cigars and other tobacco products. Since the Master Settlement Agreement in 1998, there have been declines in cigarette use, and new smoking policies are working to reduce overall adolescent tobacco use. Results of this study show that despite overall reductions in use, concurrent use of tobacco products has increased over time, most notably among female tobacco users. This study indicates that more needs to be done, especially given the increases found in both individual tobacco product use and the combination of tobacco product use, among tobacco users.

The tobacco industry has flooded the market with a diverse portfolio of tobacco products, including new and emerging products, such as e-cigarettes. In 2009 the FDA passed the Family Smoking Prevention Tobacco Control Act. This act provides the FDA the capability to extend regulatory authority to other tobacco products, including cigars. Results of this study indicate that the rates of smokeless tobacco use and cigar use are increasing among users, as well as the combination of these 2 products. While smokeless tobacco is currently regulated by FDA, cigars are not. Cigars include small cigars and cigarillos, and these may be flavored, making them more attractive products to young people. Additional policies are likely needed to focus on non-cigarette tobacco products, and the data in this study, particularly those that point to the increased cigar use overall especially among girls, will add to the FDA's case to include cigars under their regulatory control.

Overall, this is the first study to examine trends in multiple tobacco products and individual products, among tobacco users, using YRBS data, and from 1999 to 2013. The study shows there have been significant changes in both the use of individual and combinations of products, and these changes vary by sex, with young female users increasing their use of cigars and smokeless tobacco. Clearly, given the plethora of products available to young people, these trends of increased multiple tobacco product use deserves continued attention.

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by grant number [1 P50 CA180906-01] from the National Cancer Institute and the FDA Center for Tobacco Products (CTP). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH or the Food and Drug Administration.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Human Subjects Statement: The analyses in this study were exempt from IRB approval, as the data are publically available.

Contributor Information

MeLisa R. Creamer, University of Texas School of Public Health, Austin Regional Campus, Department of Health Promotion and Behavioral Sciences, Austin, TX.

Cheryl L. Perry, University of Texas School of Public Health, Austin Regional Campus, Department of Health Promotion and Behavioral Sciences, Austin, TX.

Melissa B. Harrell, University of Texas School of Public Health, Austin Regional Campus, Department of Epidemiology, Human Genetics, and Environmental Sciences, Austin, TX.

Pamela M. Diamond, University of Texas School of Public Health, Department of Health Promotion and Behavioral Sciences, Houston, TX.

References

- 1.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Preventing Tobacco Use Among Youth and Young Adults: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mathers M, Toumbourou J, Catalano R, et al. Consequences of youth tobacco use: a review of prospective behavioural studies. Addiction. 2006;101(7):948–958. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01438.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tercyak KP, Audrain J. Psychosocial correlates of alternate tobacco product use during early adolescence. Prev Med. 2002;35(2):193–198. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2002.1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Smoking--50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) 1991-2011 high school youth risk behavior survey data (on-line) [Accessed February 6, 2013]; Available at http://apps.nccd.cdc.gov/youthonline.

- 6.Arrazola RA, Kuiper NM, Dube SR. Patterns of current use of tobacco products among us high school students for 2000–2012—findings from the national youth tobacco survey. J Adolesc Health. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nasim A, Khader Y, Blank MD, et al. Trends in alternative tobacco use among light, moderate, and heavy smokers in adolescence, 1999–2009. Addict Behav. 2012;37(7):866–70. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brooks A, Gaier Larkin EM, Kishore S, Frank S. Cigars, cigarettes, and adolescents. Am J Health Behav. 2008;32(6):640–649. doi: 10.5555/ajhb.2008.32.6.640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Everett SA, Malarcher AM, Sharp DJ, et al. Relationship between cigarette, smokeless tobacco, and cigar use, and other health risk behaviors among us high school students. J Sch Health. 2000;70(6):234–240. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2000.tb07424.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saunders C, Geletko K. Adolescent cigarette smokers' and non-cigarette smokers' use of alternative tobacco products. Nicotine Tob Res. 2011;14(8):977–985. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schuster RM, Hertel AW, Mermelstein R. Cigar, cigarillo, and little cigar use among current cigarette-smoking adolescents. Nicotine Tob Res. 2013;15(5):925–31. doi: 10.1093/ntr/nts222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Soldz S, Huyser DJ, Dorsey E. Characteristics of users of cigars, bidis, and kreteks and the relationship to cigarette use. Prev Med. 2003;37(3):250–258. doi: 10.1016/s0091-7435(03)00121-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tomar SL, Alpert HR, Connolly GN. Patterns of dual use of cigarettes and smokeless tobacco among us males: findings from national surveys. Tob Control. 2010;19(2):104–109. doi: 10.1136/tc.2009.031070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mejia AB, Ling PM. Tobacco industry consumer research on smokeless tobacco users and product development. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(1):78. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.152603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carpenter CM, Connolly GN, Ayo-Yusuf OA, Wayne GF. Developing smokeless tobacco products for smokers: an examination of tobacco industry documents. Tob Control. 2009;18(1):54–59. doi: 10.1136/tc.2008.026583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burke V, Milligan R, Beilin L, et al. Clustering of health-related behaviors among 18-year-old australians. Prev Med. 1997;26(5):724–733. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1997.0198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vanyukov MM, Tarter RE, Kirillova GP, et al. Common liability to addiction and “gateway hypothesis”: theoretical, empirical and evolutionary perspective. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;123:S3–S17. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Tobacco use among middle and high school students—united states, 2011–2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64(14):381–385. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Tobacco product use among middle and high school students-united states, 2011 and 2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62(45):893. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miech RA, Johnston LD, O'Malley PM, et al. E-cigarettes surpass tobacco cigarettes among teens. [Accessed February 22, 2015]; http://www.monitoringthefuture.org.

- 21.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Methodology of the youth risk behavior surveillance system--2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62(1):1–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brener ND, Kann L, McManus T, et al. Reliability of the 1999 youth risk behavior survey questionnaire. J Adolesc Health. 2002;31(4):336–342. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(02)00339-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Data files & methods. [Accessed January 15, 2014]; http://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/yrbs/data/index.htm.

- 24.Nelson DE, Mowery P, Asman K, et al. Long-term trends in adolescent and young adult smoking in the united states: metapatterns and implications. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(5) doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.115931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nelson DE, Mowery P, Tomar S, et al. Trends in smokeless tobacco use among adults and adolescents in the united states. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(5):897. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.061580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Current tobacco use among middle and high school students —united states, 2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61:581–585. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kulbok PA, Cox CL. Dimensions of adolescent health behavior. J Adolesc Health. 2002;31(5):394–400. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(02)00422-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van Nieuwenhuijzen M, Junger M, Velderman MK, et al. Clustering of health-compromising behavior and delinquency in adolescents and adults in the dutch population. Prev Med. 2009;48(6):572–578. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2009.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]