Abstract

DNA and histone lysine methylation are dynamic chemical modifications that play a crucial role in the establishment of gene expression patterns during development. Both types of genomic methylation patterns are enzymatically regulated by the opposing activities of enzymes that introduce and remove these marks, known as methylation “writers” and “erasers”, respectively. The appropriate localization and activity of these enzymes on chromatin is, in part, regulated by chromatin “readers”, protein modules that recognize histone and DNA modifications. Such reading modules are either encoded within the same polypeptide as the catalytic domains of writers and erasers, or present in protein partners that associate with them. Here, we review recent structural, biochemical and biological studies that demonstrate that there are multiple mechanisms by which reader domains can regulate the writers and erasers of histone and DNA methylation.

Introduction

Post-translational modifications (PTMs) on histone proteins play essential roles in the establishment of transcriptional states and consequently control cellular states [1,2]. In a cell, the histone modification patterns are regulated by proteins that write, erase and read these chemical marks. A large number of PTMs have been identified on histone proteins [3]. Among them, lysine methylation is considered one of the most versatile chemical modifications. This is because (i) lysine residues can be mono-, di-, or tri-methylated and (ii) methylation of different histone residues can be associated with either gene activation or silencing [4].

Lysine methylation is tightly regulated by histone lysine methyltransferases and demethylases. Remarkably, both classes of enzymes are often associated with, and at times regulated by, one or more chromatin binding domains that recognize distinct histone methylation marks. Reader domains can either be independent polypeptides or a part of the same polypeptide that also contains the catalytic domain [5–9]. Reader domains and catalytic domains can combinatorially recognize PTMs within a single histone tail, within two tails on the same nucleosome, or within two histone tails on different nucleosomes [10]. Additionally, histone methylation can also be regulated by recognition of DNA methylation, and vice versa, enabling tight coordination of nucleosomal methylation patterns.

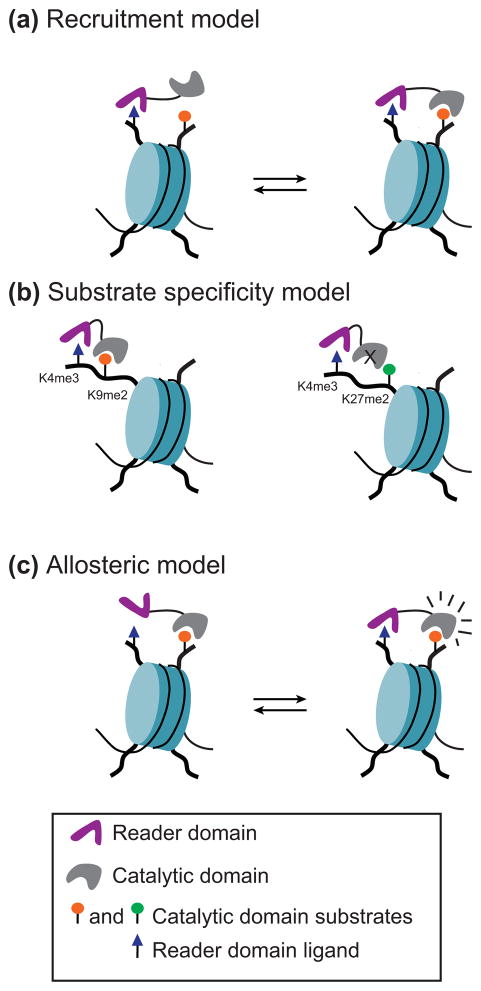

Functional coupling between domains that read and domains that write or erase methylation marks serves as a mean to (i) recruit or stabilize a catalytic activity to a specific chromatin location, (ii) regulate substrate specificity and, (iii) allosterically regulate activity (Figure 1). This review summarizes recent advances in understanding the mechanisms underlying the complex regulation of nucleosome methylation by chromatin writers, eraser and reader domains.

Figure 1.

Functional coupling between domains that read and domains that write or erase methylation marks serves as a mean to (a) recruit or stabilize a catalytic activity to a specific chromatin location, (b) regulate substrate specificity as in the case of PHF8 and KIAA1718 [reviewed in 6, 39] and, (c) allosterically regulate activity. Reader domains can either stimulate or inhibit the catalytic activity of writers and erasers. Crosstalk between a reader and a catalytic domain can occur when both are encoded in the same polypeptide or are part of two distinct polypeptides within the same protein complex. Multivalent engagement of histone modifications can occur when on the same histone (cis), on adjacent histones within the same nucleosome (intranucleosomal) or on adjacent nucleosomes (internucleosomal).

Regulation of histone lysine methyltransferases by histone reader domains within the same polypeptide

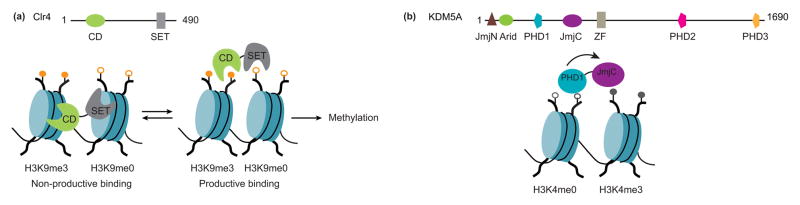

The H3K9 methyltransferase Clr4 is the Schizosaccharomyces pombe homolog of the human Suv39. Clr4 contains an N-terminal chromodomain (CD) in addition to a catalytic SET domain [11]. Early in vivo studies demonstrated that the CD recognizes tri-methylated lysine 9 on histone H3 (H3K9me3), the catalytic product of Clr4 and such binding is essential for efficient spreading of the H3K9me3 mark on chromatin [12,13]. Investigation of the activity of Clr4 on reconstituted nucleosome substrates uncovered that the CD-H3K9me3 interaction increases the methyltransferase activity of Clr4 only in the context of two adjacent nucleosomes, but not on a single nucleosome or a histone tail peptide (Figure 2a) [14]. These results suggested a model in which the role of the CD-H3K9me3 is to position Clr4 catalytic domain such that it is optimally oriented to bind to an unmethylated H3 tail on an adjacent nucleosome.

Figure 2.

Regulation of histone methylation by reader domains within the same polypeptides. (a) The H3K9 methyltransferase Clr4 contains a chromodomain (CD) reader domain (green) that recognizes H3K9me3 (orange circle), the enzymatic product of the catalytic SET domain (gray). Recognition of H3K9me3 by the CD domain stimulates H3K9 (open orange circle) methyltransferase activity by orienting the SET domain to an adjacent nucleosome. (b) The H3K4me3 histone demethylase KDM5A contains a PHD1 domain (aqua) that recognizes H3K4me0 (open gray circles). Occupancy of the PHD1 domain allosterically stimulates H3K4me3 demethylation (gray circles) by the catalytic JmjC domain (purple).

The H3K9me1,2 methyltransferases, G9a and GLP, share a similar mechanism of regulation to that observed in Clr4. In addition to the catalytic SET domain, G9a and GLP contain an ankyrin repeat reader domain that binds to H3K9me1 and H3K9me2, products of their enzymatic activities [15]. Liu et al. showed that the catalytic activities of GLP and G9a are strongly stimulated on nucleosomal substrates flanked by neighboring nucleosomes carrying H3K9 methylation [16]. However, unlike Clr4, in vivo experiments suggest that the role of the ankyrin repeat reader domain in G9a and GLP is to increase the local concentration of both enzymes on H3K9me2/1 rich regions rather than to help determine the directionality and facilitate spreading of the methyltransferase on chromatin [12–14].

Regulation of histone lysine demethylases by reader domains within the same polypeptide

KDM4A and KDM4C are JmjC-domain containing histone demethylases capable of removing tri- and di-methylation from H3K9 (H3K9me3,2) [17]. KDM4A/C contain a N-terminal catalytic domain and a C-terminal cluster of reader domains consisting of two plant homeodomain (PHD) and a double tudor domain [17]. Structural and biochemical studies demonstrate that the double tudor domain of KDM4A recognizes H3K4me3 and H4K20me3 [18,19]. In contrast, the double tudor domain of KDM4C recognizes only H3K4me3, as determined by pulldown experiments [20]. Consistent with this observation, in vivo chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by high-throughput sequencing (ChIP-seq) showed that KDM4C localizes to transcription start sites containing H3K4me3 and that such localization is dependent on the functionality of the double tudor domain [20,21]. These results suggest that trimethylated K4 and K9 on histone H3 act in a cooperative manner to recruit KDM4A and KDM4C on chromatin.

To better understand the role of H3K4me3 toward demethylation of H3K9me3, the catalytic activity of full-length KDM4A/C was further investigated biochemically. KDM4A activity toward H3K9me3 peptides increases by ~16-folds when the same peptide is also trimethylated at lysine 4 (H3K4me3/K9me3)[22]. In contrast to KDM4A, a modest (~ 2-fold) enhancement in catalysis was observed with full length KDM4C when comparing demethylation of H3K9me3 and H3K4me3/K9me3 peptides [22]. Future studies of KDM4C activity on nucleosomal substrates will help shed light on the discrepancies between the role of the double tudor domain in recruitment and activity.

Recently, a novel mode of regulation by its reader domain has been described in the histone demethylase KDM5A [23]. The KDM5 subfamily of Jumonji histone demethylases catalyzes the removal of tri-, di- and mono- methyl marks from lysine 4 of histone H3 (H3K4me3/2/1). In addition to its JmjC catalytic domain KDM5A also contains three PHD reader domains. The PHD1 preferentially recognizes unmethylated H3K4 while the PHD3 recognizes tri-methylated H3K4, the product and substrate of KDM5A catalytic domain, respectively [23,24]. Our laboratory has recently observed that binding of unmethylated H3K4 peptide by the PHD1 domain allosterically stimulates the catalytic activity of KDM5A on nucleosome substrates by 30-fold, suggesting a strong functional coupling between the PHD1 domain and the catalytic domain (Figure 2b) [23]. Given the high sequence homology of the PHD1 reader domains among members of the KDM5 family, we hypothesize that the regulation of the catalytic activity by a PHD1 domain-chromatin interaction is conserved across KDM5 enzymes. Consistent with this hypothesis, it was recently shown that abrogation of H3 tail recognition by point mutations in the PHD1 domain of KDM5B decreases H3K4 demethylation in cells [25,26]

While not yet directly tested, the PHD1 and PHD3 domains in KDM5 demethylases may synergize to regulate H3K4me3 removal on chromatin. Substrate recognition by PHD3 could serve to target KDM5 enzymes to H3K4me3 rich genomic sites thus increasing the local concentration of the enzymes. Following demethylation, the product could bind to the PHD1 domain, and this binding could then enhance the catalytic activity of the enzyme. In addition, product binding to the PHD1 domain may also increase the dwell time of the demethylase on its substrate, further contributing to the enhancement in catalysis and potentially altering the processivity of the H3K4me3 demethylation. Together, the cumulative effect of the two PHD reader domains may serve to propagate demethylation on chromatin similarly to the previously described role of the CD domain in Clr4 and EED domain in the context of PRC2 complex [12,13,27].

Coupled activities of reader and catalytic domains within protein complexes

Numerous methyltransferases and demethylases associate with large protein complexes that contain chromatin-binding proteins that may regulate the catalytic activities of writers and erasers. The Polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2), which catalyzes di- and tri-methylation of lysine 27 of histone H3 and plays an essential role in the maintenance of repressive chromatin states, represents such an example [28]. The core components of the PRC2 complex are the H3K27 methyltransferase EZH2, SUZ12, EED and RBAP46/48. Other accessory proteins of PRC2 include PHF1, JARID2 and AEBP2. By using the PRC2 as an example, we highlight the types of mechanisms of functional crosstalk between histone methyltransferases and their associated reader domains. Similar mechanisms also apply to histone demethylases, as exemplified by LSD1 and in the Drosophila KDM4A [29,30].

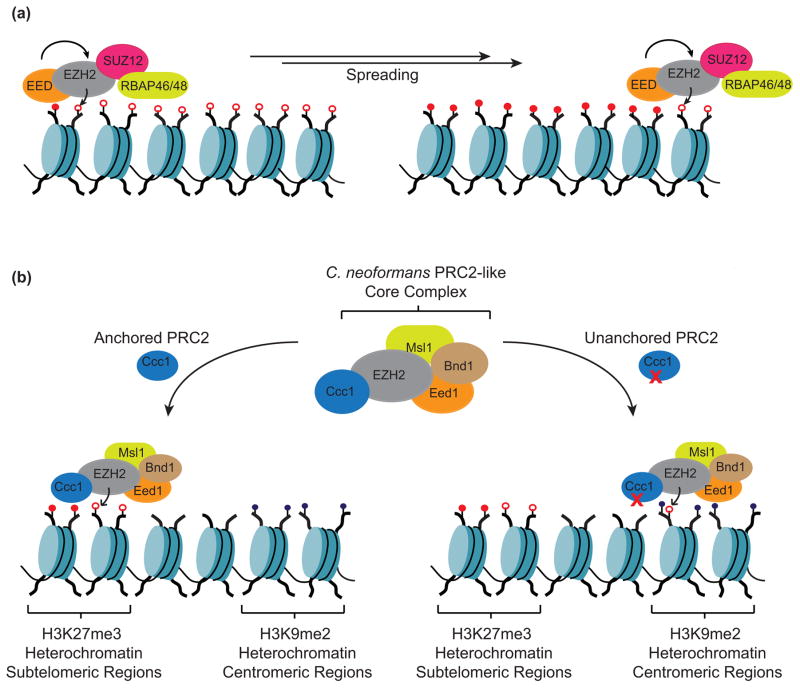

a. Product recognition by the EED stimulates PRC2 activity

The EED subunit of the PRC2 complex contains a WD40 domain that preferentially recognizes H3K27me3 [27]. In vitro biochemical studies have shown that an H3K27me3 peptide stimulates nucleosomal PRC2 activity by ~7-fold [27] (Figure 3a). Similarly, a mutation in EED that impairs its binding to H3K27me3, abrogates the activation of PRC2 catalytic activity in vitro. Consistent with these biochemical studies, the recruitment and propagation of the Drosophila PRC2 complex containing a non-functional EED subunit along the Ubx gene was affected [27].

Figure 3.

Regulation of PRC2-methyltransferase activity. (a) Representation of the mammalian PRC2 core complex. Recognition of H3K27me3 by the EED subunit allosterically stimulates H3K27 methyltransferase activity. (b) The C. neoformans PRC2-like complex subunit Ccc1 is a chromodomain-containing protein that recognizes H3K27me3. Impairment of the Ccc1-H3K27me3 complex causes a redistribution of the PRC2 complex to H3K9me2 heterochromatin suggesting a model by which Ccc1 suppresses the promiscuity of the PRC2 complex.

b. Regulation of PRC2 activity by readout of the H3K36me3 mark

PHF1 is an accessory protein that often interacts with the PRC2 complex. This protein contains a N-terminal Tudor domain that binds to H3K36me3, a mark associated with active transcription, and two C-terminal PHD domains [31]. Early biochemical studied showed that association of the tudor domain with H3K36me3 inhibits the activity of the PRC2 complex in vitro and in vivo [31,32], thus preventing deposition of H3K27 methylation at transcriptionally active genes. In contrast, a recent study showed that the tudor domain of PHF1 promotes association of PRC2 with chromatin and its spreading to H3K36me3 marked loci [33,34]. This H3K36me3-dependent deposition of the repressive H3K27me3 may enable modulation of the chromatin structure of genes undergoing dynamic changes in expression, usually going from active to a poised or repressed state. Further mechanistic studies are necessary to fully dissect the role of PHF1 in modulating the activity of PRC2 on chromatin.

c. Product recognition regulates the genomic distribution of the PRC2 complex

A PRC2-like complex has recently been identified and characterized in the budding yeast, Cryptococcus neoformans, where PRC2 seems to be responsible for the repression of subtelomeric regions [35]. The Cryptococcus neoformans PRC2 complex contains most of the mammalian ortholog members (EZH2, Eed1/EED, Msl1/RBAP46/48, but lacksSUZ12) and in addition contains two fungal-specific proteins, Ccc1 and Bnd1. Ccc1 is a chromodomain-containing protein that specifically recognizes H3K27me3, the product of PRC2 [35]. While deletion of EZH2 or EED orthologs in the C. neoformans PRC2 results in abrogation of its activity, a mutation that impairs Ccc1 binding to H3K27me3 results in a genome-wide redistribution of the complex from subtelomeric regions to centromeric regions, which are enriched in H3K9me2 (Figure 3b) [35]. Based on these data, the authors proposed that a role of product recognition by Ccc1 is to ensure PRC2 target specificity by tethering it to sites of previous action.

Cross-talk between DNA and histone methylation

DNA methylation has long been studied for its key role as a repressive mark. DNA methylation is associated with numerous biological processes, such as silencing of transposable elements, regulation of gene expression, genomic imprinting, and X-chromosome inactivation [36,37]. It was recently demonstrated that DNA and histone methylation can work synergistically to regulate chromatin structure and function [38–40]. In particular, genome-wide DNA methylation profiles indicate that DNA methylation strongly correlates with the presence of H3K9me3 and H3K4me0 [41]. Remarkably, the co-localization of DNA and histone marks is tightly regulated by the coordinated action of writers and readers. Below, we discuss a few examples of such functional coupling.

Regulation of DNA methylation by histone reader domains

In mammals, DNA methylation occurs mainly at the C5 position of cytosine (5mC) at CG sites. In humans, 5mC marks are established by the de novo methyltransferases DNMT3A/B in complex with DNMT3L, a non-catalytic regulatory protein. DNMT3A, DNMT3B and DNMT3L share an ADD (ATRX-DNMT3-DNMT3L) domain that recognizes the N-terminal tail of histone H3. DNA methylation activity of DNMT3A is linked to the recognition of unmethylated H3K4 by the ADD domain (Figure 4a) [42,43]. Interestingly, the ADD-H3 tail interaction is disrupted when H3K4 is methylated [41,44,45]. Consistent with these observations, the unmethylated H3 tail allosterically stimulates DNA methylation activity of DNMT3A in vitro, and the extent of this stimulation decreases with increased degree of H3K4 methylation [46].

Figure 4.

Cross-talk between histone and DNA methylation. (a) Domain architecture of DNMT3A. (b) A working model for the regulation of DNMT3A DNA methyltransferase activity by the recognition of histone H3. In the absence of H3, DNMT3A adopts an autoinhibitory closed conformation. Upon binding of the H3 tail to the ADD reader domain, DNMT3A switches to an active conformation that allows binding of DNA to the catalytic domain [adapted from 47]. (c) Superimposition of the autoinibitory (PDB accession number: 4U7P) and the H3-bound active conformations of DNMT3A (PDB accession number: 4U7T) [47]. ADD domain is in green, catalytic domain is gray and the histone H3 is in pink.

Using a combination of structural and biochemical studies, it was recently shown that DNMT3A exists in an autoinhibited conformation (Figure 4b,c). In this conformation, the interaction between the catalytic domain and the ADD domain inhibits binding of DNA to the catalytic site. Binding of unmodified H3, but not the H3K4me3 histone tail, to the ADD domain induces a large conformational change in the DNMT3A, releasing the autoinhibition and allowing for the binding and methylation of DNA [47] (Figure 4b,c). These observations provide a mechanistic rationale for the colocalization of DNA methylation and H3K4me0.

In plants, DNA methylation occurs in three sequence contexts: CG, CHG (where H is either A, T, or C) and CHH. Chromomethylase 3 (CMT3) is a plant-specific DNA methyltransferase responsible for CHG methylation [48]. In addition to the DNA methyltransferase domain, CMT3 contains a chromo and a bromo adjacent homology (BAH) reader domain, both of which, independently, recognize the H3K9me2 mark [49]. Structural and functional studies of CMT3 have shown that chromatin association and activity of this enzyme in vivo require the dual recognition of H3K9me2 by the BAH and the CD [49]. Further structural and biochemical studies will be required to fully elucidate the molecular details of how the dual histone tail recognition by the BAH and the CD domains are coupled to DNA methylation in CMT3.

Regulation of histone methylation by readout of DNA methylation

Kryptonite (KYP), a plant specific H3K9 methyltransferase, provides an additional example of functional coupling between catalytic and non-catalytic domains required for the maintenance of DNA methylation [50]. In addition to the C-terminal catalytic domains, KYP contains an N-terminal SRA (SET and RING-associated) domain that preferentially binds to methylated DNA [51]. A structural model of KYP with the nucleosome suggests simultaneous binding of nucleosomal DNA and the H3 tail within the same nucleosome [52].

The coordinated function of CMT3 and KYP in plants is one of the most compelling example of a functional crosstalk between histone and DNA methylation: KYP-dependent histone methylation provides a binding site for CMT3-dependent methylation of CHG DNA, which in turn promotes further recruitment and activity of KYP on chromatin, thus re-enforcing heterochromatin silencing.

Conclusions

Over the years, it became evident that at the basis of a biological process lies in a complex and multivalent engagement of chemical marks deposited by a network of proteins that write, erase and read these marks [10]. This review aimed to summarize recent findings on histone and DNA methyltransferases and demethylases. These are multi-domain proteins, often part of large protein complexes, acting on a multisubunit nucleoprotein substrate, the nucleosome. More importantly, the work presented here demonstrates how the activity of this class of chromatin modifying enzymes appears to be tightly regulated by non-catalytic domains that read modifications on DNA and histone proteins.

As we continue to mechanistically dissect the activity of both histone and DNA methyltransferases and demethylases, it will be fundamentally important to expand our investigations from studies on isolated domains to interrogations of how these domains work together. Furthermore, expanding these studies from histone tail peptides to nucleosome substrates will further define the mechanistic underpinnings of chromatin-mediated regulation. While current approaches are still technically challenging, we foresee that continuous improvements in biochemical and biophysical approaches will stimulate these types of studies [53].

Additionally, we anticipate that functional coupling between catalytic and non-catalytic activities can be exploited to manipulate cells. Indeed, specific small molecule modulators that target cross-talk between domains can help further elucidate how chromatin modifying enzymes function in vivo, thereby informing our understanding of their roles in physiology and disease.

Highlights.

The activity of writers and erasers of chromatin marks is coupled to the function of reader modules.

Reader domains regulate recruitment, substrate specificity and catalysis of chromatin modifying enzymes.

Histone and DNA methylation patterns are tightly coordinated.

Acknowledgments

We thank Lindsey Pack, Daniele Canzio and Hiten Madhani for comments on this review, and Searle Scholars Program, UCSF Program for Breakthrough Biomedical Research and Nina Ireland Program for Lung Health for research support.

Glossary

- Histone demethylases (erasers)

-

KDM4A- human H3K9 histone demethylase

KDM4C- human H3K9 histone demethylase

KDM5A- human H3K4 histone demethylase

KDM5B- human H3K4 histone demethylase

- Histone methyltranferases (writers)

-

Clr4- S. pombe H3K9 methyltransferase

G9a- human H3K9 methyltransferase,

GLP- human H3K9 methyltransferase,

Kryptonite (KYP)- plant H3K9 methyltransferase

EZH2- H3K27 methyltransferase in the PRC2 complex

- Histone reader domains (readers)

-

Chromodomain(CD)

Ankyrin repeat

Plant homeodomain (PHD)

Double tudor domain

Bromo adjacent homology (BAH)

ADD (ATRX-DNMT3-DNMT3L)

WD40 domain

- DNA methyltranferase (writers)

-

Chromomethylase 3 (CMT3)- CHG methylation in plants

DNMT3A- human de novo DNA methyltransferases at CG sites

DNMT3B- human de novo DNA methyltransferases at CG sites

- DNA reader domain (readers)

SRA (SET and RING-associated) recognize methylated DNA

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Strahl BD, Allis CD. The language of covalent histone modifications. Nature. 2000;403:41–45. doi: 10.1038/47412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jenuwein T, Allis CD. Translating the histone code. Science. 2001;293:1074–1080. doi: 10.1126/science.1063127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3*.Rothbart SB, Strahl BD. Interpreting the language of histone and DNA modifications. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2014;1839:627–643. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2014.03.001. A recent overview of know histone and DNA modifications. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martin C, Zhang Y. The diverse functions of histone lysine methylation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:838–849. doi: 10.1038/nrm1761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Musselman CA, Khorasanizadeh S, Kutateladze TG. Towards understanding methyllysine readout. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2014;1839:686–693. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2014.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Upadhyay AK, Horton JR, Zhang X, Cheng X. Coordinated methyl-lysine erasure: structural and functional linkage of a Jumonji demethylase domain and a reader domain. Current Opinion in Structural Biology. 2011;21:750–760. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2011.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Verrier L, Vandromme M, Trouche D. Histone demethylases in chromatin cross-talks. Biology of the Cell. 2012;103:381–401. doi: 10.1042/BC20110028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Musselman CA, Kutateladze TG. Handpicking epigenetic marks with PHD fingers. Nucleic Acids Research. 2011;39:9061–9071. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lalonde ME, Cheng X, Cote J. Histone target selection within chromatin: an exemplary case of teamwork. Genes & Development. 2014;28:1029–1041. doi: 10.1101/gad.236331.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ruthenburg AJ, Li H, Patel DJ, David Allis C. Multivalent engagement of chromatin modifications by linked binding modules. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:983–994. doi: 10.1038/nrm2298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ivanova AV, Bonaduce MJ, Ivanov SV, Klar AJ. The chromo and SET domains of the Clr4 protein are essential for silencing in fission yeast. Nat Genet. 1998;19:192–195. doi: 10.1038/566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang K, Mosch K, Fischle W, Grewal SIS. Roles of the Clr4 methyltransferase complex in nucleation, spreading and maintenance of heterochromatin. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2008;15:381–388. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nakayama JI. Role of histone H3 lysine 9 methylation in epigenetic control of heterochromatin assembly. Science. 2001;292:110–113. doi: 10.1126/science.1060118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Al-Sady B, Madhani HD, Narlikar GJ. Division of labor between the chromodomains of HP1 and Suv39 methylase enables coordination of heterochromatin spread. Molecular Cell. 2013;51:80–91. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Collins RE, Northrop JP, Horton JR, Lee DY, Zhang X, Stallcup MR, Cheng X. The ankyrin repeats of G9a and GLP histone methyltransferases are mono- and dimethyllysine binding modules. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2008;15:245–250. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu N, Zhang Z, Wu H, Jiang Y, Meng L, Xiong J, Zhao Z, Zhou X, Li J, Li H, et al. Recognition of H3K9 methylation by GLP is required for efficient establishment of H3K9 methylation, rapid target gene repression, and mouse viability. Genes & Development. 2015;29:379–393. doi: 10.1101/gad.254425.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klose RJ, Kallin EM, Zhang Y. JmjC-domain-containing proteins and histone demethylation. Nat Rev Genet. 2006;7:715–727. doi: 10.1038/nrg1945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee J, Thompson JR, Botuyan MV, Mer G. Distinct binding modes specify the recognition of methylated histones H3K4 and H4K20 by JMJD2A-tudor. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2007;15:109–111. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang Y, Fang J, Bedford MT, Zhang Y, Xu R-M. Recognition of histone H3 lysine-4 methylation by the double tudor domain of JMJD2A. Science. 2006;312:748–751. doi: 10.1126/science.1125162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pedersen MT, Agger K, Laugesen A, Johansen JV, Cloos PAC, Christensen J, Helin K. The demethylase JMJD2C localizes to H3K4me3-positive transcription start sites and is dispensable for embryonic development. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 2014;34:1031–1045. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00864-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Das PP, Shao Z, Beyaz S, Apostolou E, Pinello L, De Los Angeles A, O’Brien K, Atsma JM, Fujiwara Y, Nguyen M, et al. Distinct and Combinatorial Functions of Jmjd2b/Kdm4b and Jmjd2c/Kdm4c in Mouse Embryonic Stem Cell Identity. Molecular Cell. 2014;53:32–48. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lohse B, Helgstrand C, Kristensen JBL, Leurs U, Cloos PAC, Kristensen JL, Clausen RP. Posttranslational modifications of the histone 3 tail and their impact on the activity of histone lysine demethylases in vitro. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e67653. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0067653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23**.Torres IO, Kuchenbecker KM, Nnadi CI, Fletterick RJ, Kelly MJS, Fujimori DG. Histone demethylase KDM5A is regulated by its reader domain through a positive-feedback mechanism. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6204. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7204. This manuscript describe an allosteric regulatory mechanism in demethylase KDM5A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang GG, Song J, Wang Z, Dormann HL, Casadio F, Li H, Luo J-L, Patel DJ, Allis CD. Haematopoietic malignancies caused by dysregulation of a chromatin-binding PHD finger. Nature. 2009;459:847–851. doi: 10.1038/nature08036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Klein BJ, Piao L, Xi Y, Rincon-Arano H, Rothbart SB, Peng D, Wen H, Larson C, Zhang X, Zheng X, et al. The histone-H3K4-specific demethylase KDM5B binds to its substrate and product through distinct PHD fingers. Cell Reports. 2014;6:325–335. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.12.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang Y, Yang H, Guo X, Rong N, Song Y, Xu Y, Lan W, Zhang X, Liu M, Xu Y, et al. The PHD1 finger of KDM5B recognizes unmodified H3K4 during the demethylation of histone H3K4me2/3 by KDM5B. Protein Cell. 2014;5:837–850. doi: 10.1007/s13238-014-0078-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Margueron R, Justin N, Ohno K, Sharpe ML, Son J, DruryIII WJ, Voigt P, Martin SR, Taylor WR, De Marco V, et al. Role of the polycomb protein EED in the propagation of repressive histone marks. Nature. 2009;461:762–767. doi: 10.1038/nature08398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Margueron R, Reinberg D. The Polycomb complex PRC2 and its mark in life. Nature. 2011;469:343–349. doi: 10.1038/nature09784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lan F, Collins RE, De Cegli R, Alpatov R, Horton JR, Shi X, Gozani O, Cheng X, Shi Y. Recognition of unmethylated histone H3 lysine 4 links BHC80 to LSD1-mediated gene repression. Nature. 2007;448:718–722. doi: 10.1038/nature06034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lin C-H, Li B, Swanson S, Zhang Y, Florens L, Washburn MP, Abmayr SM, Workman JL. Heterochromatin protein 1a stimulates histone H3 lysine 36 demethylation by the drosophila KDM4A demethylase. Molecular Cell. 2008;32:696–706. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Musselman CA, Avvakumov N, Watanabe R, Abraham CG, Lalonde M-E, Hong Z, Allen C, Roy S, Nuñez JK, Nickoloff J, et al. Molecular basis for H3K36me3 recognition by the Tudor domain of PHF1. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2012;19:1266–1272. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yuan W, Xu M, Huang C, Liu N, Chen S, Zhu B. H3K36 methylation antagonizes PRC2-mediated H3K27 methylation. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2011;286:7983–7989. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.194027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cai L, Rothbart SB, Lu R, Xu B, Chen W-Y, Tripathy A, Rockowitz S, Zheng D, Patel DJ, Allis CD, et al. An H3K36 methylation-engaging tudor motif of polycomb-like proteins mediates PRC2 complex targeting. Molecular Cell. 2013;49:571–582. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.11.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sarma K, Margueron R, Ivanov A, Pirrotta V, Reinberg D. Ezh2 requires PHF1 to efficiently catalyze H3 lysine 27 trimethylation in vivo. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 2008;28:2718–2731. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02017-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35*.Dumesic PA, Homer CM, Moresco JJ, Pack LR, Shanle EK, Coyle SM, Strahl BD, Fujimori DG, Yates JR, III, Madhani HD. Product binding enforces the genomic specificity of a yeast polycomb repressive complex. Cell. 2015;160:204–218. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.11.039. Characterization of PRC2-like complex in C. neoformans. Product recognition suppresses latent promiscuity of PRC2 complex. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36*.Li E, Zhang Y. DNA methylation in mammals. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology. 2014;6:a019133–a019133. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a019133. Exhaustive review on current knowledge about DNA methylation. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schübeler D. Function and information content of DNA methylation. Nature. 2015;517:321–326. doi: 10.1038/nature14192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cedar H, Bergman Y. Linking DNA methylation and histone modification: patterns and paradigms. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10:295–304. doi: 10.1038/nrg2540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39*.Cheng X. Structural and functional coordination of DNA and histone methylation. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology. 2014;6:a018747–a018747. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a018747. This review summarizes the structural aspects of enzymes that catalyze methylation and demethylation of chromatin and highlight functional link between histone and DNA methylation. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Du J, Patel DJ. Structural biology-based insights into combinatorial readout and crosstalk among epigenetic marks. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1839:719–727. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2014.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Meissner A, Mikkelsen TS, Gu H, Wernig M, Hanna J, Sivachenko A, Zhang X, Bernstein BE, Nusbaum C, Jaffe DB, et al. Genome-scale DNA methylation maps of pluripotent and differentiated cells. Nature. 2008;454:766–770. doi: 10.1038/nature07107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ooi SKT, Qiu C, Bernstein E, Li K, Jia D, Yang Z, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Lin S-P, Allis CD, et al. DNMT3L connects unmethylated lysine 4 of histone H3 to de novo methylation of DNA. Nature. 2007;448:714–717. doi: 10.1038/nature05987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Otani J, Nankumo T, Arita K, Inamoto S, Ariyoshi M, Shirakawa M. Structural basis for recognition of H3K4 methylation status by the DNA methyltransferase 3A ATRX–DNMT3–DNMT3L domain. EMBO Rep. 2009;10:1235–1241. doi: 10.1038/embor.2009.218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang Y, Jurkowska R, Soeroes S, Rajavelu A, Dhayalan A, Bock I, Rathert P, Brandt O, Reinhardt R, Fischle W, et al. Chromatin methylation activity of Dnmt3a and Dnmt3a/3L is guided by interaction of the ADD domain with the histone H3 tail. Nucleic Acids Research. 2010;38:4246–4253. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hu J-L, Zhou BO, Zhang R-R, Zhang K-L, Zhou J-Q, Xu G-L. The N-terminus of histone H3 is required for de novo DNA methylation in chromatin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:22187–22192. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905767106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li B-Z, Huang Z, Cui Q-Y, Song X-H, Du L, Jeltsch A, Chen P, Li G, Li E, Xu G-L. Histone tails regulate DNA methylation by allosterically activating de novo methyltransferase. Cell Research. 2011;21:1172–1181. doi: 10.1038/cr.2011.92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47**.Guo X, Wang L, Li J, Ding Z, Xiao J, Yin X, He S, Shi P, Dong L, Li G, et al. Structural insight into autoinhibition and histone H3-induced activation of DNMT3A. Nature. 2015;517:640–644. doi: 10.1038/nature13899. This manuscripts provides structural insight into the allosteric stimulation of DNMT3A by histone H3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Law JA, Jacobsen SE. Establishing, maintaining and modifying DNA methylation patterns in plants and animals. Nat Rev Genet. 2010;11:204–220. doi: 10.1038/nrg2719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Du J, Zhong X, Bernatavichute YV, Stroud H, Feng S, Caro E, Vashisht AA, Terragni J, Chin HG, Tu A, et al. Dual binding of chromomethylase domains to H3K9me2-containing nucleosomes directs DNA methylation in plants. Cell. 2012;151:167–180. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.07.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jackson JP, Lindroth AM, Cao X, Jacobsen SE. Control of CpNpG DNA methylation by the KRYPTONITE histone H3 methyltransferase. Nature. 2002;416:556–560. doi: 10.1038/nature731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Johnson LM, Bostick M, Zhang X, Kraft E, Henderson I, Callis J, Jacobsen SE. The SRA methyl-cytosine-binding domain links DNA and histone methylation. Current Biology. 2007;17:379–384. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52*.Du J, Johnson LM, Groth M, Feng S, Hale CJ, Li S, Vashisht AA, Gallego-Bartolome J, Wohlschlegel JA, Patel DJ, Jacobsen SE. Mechanism of DNA methylation-directed histone methylation by KRYPTONITE. Molecular Cell. 2014;55:495–504. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.06.009. This manuscript describes the structure of KYP in complex with H3 peptide substrate and DNA. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chatterjee C, Muir TW. Chemical approaches for studying histone modifications. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2010;285:11045–11050. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R109.080291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]