Abstract

Approximately 30% of Americans suffer from chronic pain disorders, such as fibromyalgia (FM), which can cause debilitating pain. Many pain-killing drugs prescribed for chronic pain disorders are highly addictive, have limited clinical efficacy, and do not treat the cognitive symptoms reported by many patients. The neurobiological substrates of chronic pain are largely unknown, but evidence points to altered dopaminergic transmission in aberrant pain perception. We sought to characterize the dopamine (DA) system in individuals with FM. Positron emission tomography (PET) with [18F]fallypride (FAL) was used to assess changes in DA during a working memory challenge relative to a baseline task, and to test for associations between baseline D2/D3 availability and experimental pain measures. Twelve female subjects with FM and eleven female controls completed study procedures. Subjects received one FAL PET scan while performing a “2-back” task, and one while performing a “0-back” (attentional control, “baseline”) task. FM subjects had lower baseline FAL binding potential (BP) in several cortical regions relative to controls, including anterior cingulate cortex. In FM subjects, self-reported spontaneous pain negatively correlated with FAL BP in the left orbitofrontal cortex and parahippocampal gyrus. Baseline BP was significantly negatively correlated with experimental pain sensitivity and tolerance in both FM and CON subjects, although spatial patterns of these associations differed between groups. The data suggest that abnormal DA function may be associated with differential processing of pain perception in FM. Further studies are needed to explore the functional significance of DA in nociception and cognitive processing in chronic pain.

Keywords: dopamine, positron emission tomography, pain, fallypride, fibromyalgia, imaging, chronic pain

INTRODUCTION

Nociception is a normal process that is crucial for an organism’s survival. However, in conditions such as fibromyalgia (FM), there is likely a dysfunction in perceptual processing which results in constant (or chronic) pain. An estimated 30.7% of Americans suffer from various chronic pain disorders (Johannes et al. 2010), which can negatively affect multiple facets of everyday life, often to the point of debilitation. Depression, anxiety, and cognitive complaints are highly comorbid with chronic pain disorders (Asmundson and Katz 2009; Berryman et al. 2013; Gureje 2007). Unfortunately, many of the pain-killing medications prescribed to individuals with chronic pain are highly addictive, have limited clinical efficacy, and do not treat the cognitive symptoms reported by patients (Ballantyne and Shin 2008; Kuijpers et al. 2011). Therefore, there is a critical need to elucidate the neural substrates of pain perception in order to inform development of more effective therapeutic strategies.

Recent evidence from human imaging studies in healthy controls implicates a regulatory role for dopamine (DA) in nociception during experimentally evoked pain (Hagelberg et al. 2002; Wood et al. 2007; Martikainen et al. 2005; Pertovaara et al. 2004; Scott et al. 2006). Given this evidence, it is possible that aberrant DA signaling may be linked to the perception of moderate to severe chronic pain. Indeed, alterations of DA function have been documented in several chronic pain disorders, including FM (Wood et al. 2009; Wood et al. 2007), restless legs syndrome (Cervenka et al. 2006), burning mouth syndrome (Hagelberg et al. 2003b), and atypical facial pain (Hagelberg et al. 2003a). Whereas these studies focused on striatal DA function, very little is known about the role of cortical DA function in chronic pain.

In addition to a putative role in nociception, DA is essential for cognitive function (for a comprehensive review, see Nieoullon 2002). Therefore, it is possible that DA may mediate the cognitive complaints often reported by chronic pain patients (McCracken and Iverson 2001; Williams et al. 2011). Consistent with this hypothesis, recent BOLD fMRI data suggest that individuals with FM have a significantly lower level of working memory-induced brain activation compared to controls (Seo et al. 2012), which is supportive of the concept that cortical cognitive processing may be altered in FM. However, the neurochemical basis for these observations is unclear.

In order to help elucidate the dopaminergic (DAergic) contributions to the pain experience and potential cognitive compromise in chronic pain disorders, we conducted a pilot study in individuals with FM using positron emission tomography (PET) and [18F]fallypride (FAL). The primary objective of the current study was to ascertain how striatal and extrastriatal DA signaling might differ in individuals with chronic pain. Although many pain disorders may share common neurological substrates, the literature suggests that neurochemical differences exist among various pain populations (Apkarian et al. 2009). Thus, in order to reduce variance within our sample, we chose to study individuals that fit diagnostic criteria for FM syndrome.

We hypothesized that: (1) FM and CON groups would have different central DA tone (reflected by differences in baseline DA D2/D3 receptor binding); (2) relative to controls, FM subjects would exhibit different patterns of DA release in response to a working memory (WM) task; and (3) baseline DA D2/D3 availability would be associated with spontaneous self-reported pain levels in FM subjects, and with experimental pain measures in both FM and CON subjects.

METHODS

All study procedures were approved by the Indiana University Institutional Review Board and performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the Belmont Report. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients prior to participation in the study. Subjects were recruited by local advertising in the greater Indianapolis area. Twelve female subjects with fibromyalgia (FM) and twelve control female subjects (CON) completed all study procedures. Subjects underwent a screening interview that included the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV disorders (SCID) I and II, the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI; Beck et al. 1961), the State-Trait Anxiety Scale (STAI; Spielberger 1983), the Positive and Negative Affect Scale (PANAS; Watson et al. 1988), the Edinburgh Handedness Inventory (Oldfield 1971), the Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence (Pomerleau et al. 1994), and the Time Line Follow Back calendar for recent drinking (TLFB; Sobell et al. 1986). Two FM subjects endorsed current major depressive episode and were taking prescription antidepressants. The control group included two subjects matched for diagnosis of current major depressive episode and medication status. Exclusion criteria were: age less than 18 or greater than 45, history of Axis I disorders (excluding mood and anxiety disorders), history of seizures, intake of >14 alcoholic drinks per week, current use of illicit drugs (sporadic marijuana use excepted), current use of medications with known dopaminergic interactions (including selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors and daily use of prescription opiates), contraindication for MRI, and a positive urine toxicology screen (Q-10, Proxam) on screening and/or PET imaging days. Two FM subjects reported sporadic, as-needed use of prescription opiate painkillers, and another reported as-needed use of benzodiazepines. However, no subjects tested positive for either drug class on either scan day. FM-specific exclusion criteria were: failure to meet diagnostic criteria for FM (Wolfe et al. 1990) as determined by a pain specialist (co-author P.M.), and presentation of any comorbid pain disorder(s). Subjects received two [18F]fallypride (FAL) PET scans, conducted on separate days. Scan order was counterbalanced across subjects. The baseline FAL scan was acquired while subjects performed a control attention task (BL; 0-back task). The challenge FAL scan was acquired while subjects performed a working memory task (WM; 2-back task).

Subjective Pain Ratings

Questionnaires

Multiple self-reported pain assessments were conducted. At the beginning of each scan day, subjects completed the short-form McGill Pain Questionnaire (MPQ; Melzack 1987), Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire (FIQ; Burckhardt et al. 1991), and the Brief Pain inventory (BPI; Cleeland and Ryan 1994). Additionally, to characterize self-reported pain intensity during scanning, subjects periodically rated their current pain on a computerized visual analog scale (VAS), anchored by 0 (no pain at all) and 100 (worst pain possible). Subjects were prompted to respond to the VAS query every ten minutes throughout scanning, for a total of 15 responses. For each subject and each scan, the average VAS score over the entire scan session was calculated.

Pressure Sensitivity Testing

Six of the 18 FM “tender points” were selected for determination of each subject’s mechanical pain sensitivity and tolerance: bilateral second rib, bilateral trapezius muscle, and the bilateral medial fat pads of the knee (Wolfe et al. 1990). A JTech Commander Algometer (JTech Medical, Salt Lake City, UT) with a rubber disc of 1cm2 was applied at 90° to each of these points. Pressure was initially applied at an approximate rate of 3 Newtons/cm2/s to determine subjects’ sensitivity (that is, the level of pressure at which the subject initially perceives the sensation of pain). To assess pain tolerance, pressure was gradually increased until the pain was almost unbearable. Pressure was withdrawn immediately after subjects indicated their tolerance point. Both sensitivity and tolerance were recorded in N/cm2. Mechanical sensitivity and tolerance were assessed the morning of each scan day. Measurements of sensitivity and tolerance, respectively, were averaged across all six tender points for each day.

Cognitive Testing

N-back Task

“0-back” (BL) and “2-back” (WM) tasks were modified versions used by McDonald et al. (2012), and programmed in E-prime 2.0 software (Psychology Software Tools Inc., Sharpsburg, PA).

For each run of the “0-back” task, subjects were given a target letter prior to initiation of the task, and instructed to respond each time a stimulus letter matched the target letter.

For each run of the “2-back” task, subjects were instructed to respond when a stimulus letter matched a stimulus presented two back in the letter sequence.

During both tasks, subjects were presented with stimulus letters (all consonants, excluding L, W, and Y) for 2s with a blank screen inter-stimulus interval of 1.5s. Each task run consisted of 90 stimulus presentations, with 23 potential correct responses. Tasks were presented to subjects on a computer monitor situated outside the gantry, in full view of the subject. Initiation of tasks began five minutes prior to FAL injection. Individual task runs were presented four times, with a ~5 minute break between runs. Prior to tracer injection, study personnel ensured that the subject was able to easily see, read, and perform the task without significant head movement. Short practice sessions were conducted prior to scanning to ensure the subject understood task requirements. Task responses were made via a wireless mouse located on a table next to the scanner bed. Responses were given by clicking the left mouse button.

The number of correct responses, false positive responses, omitted responses, and respective reaction times were automatically recorded. Percent correct (adjusted for guessing) and average reaction time were calculated as outcome variables.

Additional Cognitive Tests

Three additional cognitive tests were administered prior to scanning on the baseline (“0-back”) scan day. The Paced Auditory Serial Addition Task (Gronwall 1977), and age-scaled scores from the Arithmetic and Digit Span subtests of the WAIS-III (Wechsler 1997) were administered to assess attention and working memory performance.

Image Acquisition

A magnetized prepared rapid gradient echo (MP-RAGE) magnetic resonance image (MRI) was acquired using a Siemens 3T Trio-Tim for anatomic coregistration and processing of PET data. Acquisition of [18F]fallypride (FAL) data was similar to that described previously (Albrecht et al. 2014). Briefly, FAL was synthesized in the Department of Radiology and Imaging Sciences radiochemistry facilities (Gao et al. 2010). FAL PET scans were acquired on a Siemens ECAT HR+ (3D mode; septa retracted). FAL PET scans were initiated with an IV FAL infusion into the antecubital vein over the course of 1.5 minutes. The dynamic PET acquisition was split into two segments for subject comfort (Christian et al. 2006). The first half of dynamic acquisition was 70 min (6 × 30s, 7 × 60s, 10 × 120s, 10 × 300s). Following this segment, the subject was removed from the scanner for a ~20 min break period to stretch and use the restroom if needed. The second half of dynamic acquisition lasted 80 min (16 × 300s). A schematic of the scan day timeline is shown in Online Resource 1.

Image Processing

Processing of FAL data has been described previously (Albrecht et al. 2014). Dynamic FAL PET data were reconstructed with Siemens ECAT software, v7.2.2. Three-dimensional data were rebinned into 2D sinograms with Fourier rebinning. Data were corrected for attenuation, randoms, and scatter. PET images were generated via filtered back-projection of sinograms, using a 5mm Hanning filter. MRI and dynamic PET images were converted to Neuroimaging Informatics Technology Initiative (NIfTI) format (http://nifti.nimh.nih.gov/) and processed with SPM8. A mean PET image that contained a mixture of blood flow and specific binding (i.e. showed good gray to white matter contrast in both cortical and sub-cortical regions) was created using the realignment algorithm. This mean PET image was coregistered to the subject’s anatomic MRI using the mutual information algorithm in SPM8. Motion correction was implemented with frame-by-frame coregistration, using the MRI-coregistered mean PET as the target image. Each subject’s MRI was spatially normalized to Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) space and the transformation matrix obtained from the spatial normalization step was then applied to the motion-corrected PET data from each subject.

Voxel-wise Analysis

Dopamine (DA) D2/D3 receptor binding was indexed with binding potential relative to nondisplaceable binding (BPND; for notational simplicity, we will use the term BP), which is operationally defined as fND*Bavail/KD (Innis et al. 2007). FAL BP can be influenced by both the amount of DA D2/D3 receptors available for binding (Bavail) and endogenous DA concentration (which affects both Bavail and KD, the dissociation constant for FAL). fND is a term that represents unbound radioligand in tissue (please see Innis et al., 2007, for explicit tracer kinetic modeling definitions). Cerebellar gray matter (vermis excluded) was used as the reference region (tissue that contains few to no D2/D3 receptors). Individual cerebellar regions of interest (ROIs) were created for each subject in order to extract cerebellar time activity curves. BP was estimated at each brain voxel with Logan reference graphical analysis (Logan et al. 1996) using the cerebellar time activity curve as the input function. t* was set at 25 data points in “stretched” time. The resulting parametric BP images were smoothed with an 8mm Gaussian kernel (Costes et al. 2005; Picard et al. 2006; Ziolko et al. 2006). Voxels in the parametric BP images that had values < 0.1 were excluded from further analysis to ensure that only reliably estimated BP values from both scans were considered.

Statistical Analysis

To assess group differences in demographic, affective, pain, and cognitive variables, independent t-tests were conducted for continuous and ordinal data; frequency was assessed with chi-squared tests. Tracer parameters were analyzed with a one-way ANOVA with group, scan, and group*scan as factors. Analyses were conducted with SPSS 21, with a two-tailed significance threshold of p < 0.05.

To analyze FAL BP data, parameteric images were entered into a 2-scan (BL, WM) × Group (CON, FM) full factorial model in SPM8. Model contrasts tested for baseline differences in FAL BP between groups, and for main effects of the working memory task. Voxel-wise regression models were used to test for relationships between baseline BP and pain metrics (in-scan VAS ratings, experimental pain tolerance, experimental pain sensitivity). In all analyses, an average gray matter map across all subjects was used to create an inclusive mask. Given the exploratory nature of the study, statistical threshold was set at p < 0.005, uncorrected, with cluster extent threshold k = 10. BLBP refers to BP during the baseline (“0-back”) condition, and WMBP refers to BP during the working memory (“2-back”) condition. Any putative differences in BP between BL and WM scan conditions would be attributed to changes in endogenous DA concentration (i.e., decreases in task BP relative to baseline indicate increases in DA; conversely, increases in BP indicate decreases in DA). Significant clusters from the voxel-wise analyses were defined as regions of interest (ROI). To describe the effect sizes, average ROI BP values for the clusters were extracted from parametric images using the MarsBaR toolbox (http://marsbar.sourceforge.net/).

Baseline image data for one control subject were unusable. This subject was subsequently excluded from all analyses reported herein.

RESULTS

Subject Characteristics

Subject demographics and affective characteristics are shown in Table 1. Groups were balanced for age, race, education, tobacco-smoking status, Axis I disorders, and medication status. FM subjects reported significantly higher depressive symptoms than CON subjects (p < 0.05). There were no group differences in the other affective scales.

Table 1.

Subject Demographics and Affective Measures

| Variable | FM (n = 12) | CON (n = 11) |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 28.3 ± 6.2 | 28.4 ± 7.3 |

| Race | 10C; 2AA | 10C; 1AA |

| Handedness | 11R; 1L | 10R; 1L |

| Education | 14.8 ± 2.4 | 15.7 ± 2.1 |

| Tobacco smokers | 3 | 2 |

| Presence of Axis I disorder | 2 | 2 |

| Medications | ||

| Antidepressantsa | 2 | 2 |

| Pregabalin | 2 | 0 |

| Benzodiazepines (as needed) | 1 | 0 |

| Opiates (as needed) | 2 | 0 |

| Affective inventories | ||

| BDI | 7.40 ± 4.6* | 2.40 ± 3.2 |

| STAI – state | 28.9 ± 9.1 | 26.7 ± 7.0 |

| STAI – trait | 32.4 ± 10 | 28.5 ± 6.7 |

| PANAS – positive | 34.6 ± 7.4 | 36.8 ± 8.5 |

| PANAS – negative | 17.4 ± 8.3 | 14.1 ± 5.8 |

All variables are presented as average ± s.d. unless otherwise specified. FM: fibromyalgia; CON: control; BDI: Beck Depression Inventory; STAI: State-Trait Anxiety Inventory; PANAS: Positive and Negative Affect Scale; C: Caucasian; AA: African American; R: right-handed; L: left-handed

indicates significant group differences at p < 0.05

Selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors were not permitted on this study

FAL Tracer Characteristics

There were no effects of group, scan, or group*scan on either injected radioactivity (FM BL: 193.4 ± 14.8 MBq; FM WM: 192.8 ± 13.7 MBq; CON BL: 188.6 ± 14.4 MBq; CON WM: 187.6 ± 23.9 MBq) or injected mass (FM BL: 0.058 ± 0.04 nmol/kg; FM WM: 0.056 ± 0.04 nmol/kg; CON BL: 0.053 ± 0.03 nmol/kg; CON WM: 0.064 ± 0.03 nmol/kg).

Pain Metrics

Pain metrics for FM and CON subjects are displayed in Table 2. Compared to CON, FM subjects reported significantly higher pain on every pain questionnaire, had higher VAS pain ratings during scanning, and had lower mechanical pain sensitivity and tolerance. Group differences were significant on both baseline and working memory scan days. Within-group paired-t tests revealed no significant effects of scan day (BL, WM) on any pain metric for either FM or CON groups (p > 0.05).

Table 2.

Subjective Pain Metrics

| Variable | FM (n = 12) | CON (n = 11) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BL | WM | BL | WM | |

| MPQ | ||||

| Sensory (0 – 33) | 12.3 ± 5.5* | 12.5 ± 6.8** | 0.18 ± 0.4 | 0.18 ± 0.4 |

| Affective (0 – 12) | 4.25 ± 2.7* | 3.75 ± 2.7** | 0.09 ± 0.3 | 0.09 ± 0.3 |

| Present pain (0 – 100) | 44.3 ± 25* | 43.4 ± 27** | 0.18 ± 0.6 | 0.09 ± 0.3 |

| FIQ (0 – 100) | 51.8 ± 14* | 49.7 ± 16** | 5.23 ± 12 | 4.80 ± 12 |

| BPI | ||||

| Worst pain (0 – 10) | 6.83 ± 1.1* | 6.54 ± 1.9** | 0.36 ± 0.7 | 0.45 ± 0.8 |

| Least pain (0 – 10) | 2.83 ± 1.6* | 3.33 ± 2.3** | 0.09 ± 0.3 | 0.18 ± 0.6 |

| Average pain (0 – 10) | 5.21 ± 1.6* | 5.25 ± 1.9** | 0.36 ± 0.9 | 0.0 |

| Pain interference (0 – 10) | 4.68 ± 2.5* | 4.94 ± 2.4** | 0.35 ± 1.1 | 0.34 ± 1.0 |

| Algometry (N/cm2) | ||||

| Average sensitivity | 9.28 ± 5.3* | 9.05 ± 5.5** | 22.2 ± 6.5 | 22.5 ± 9.0 |

| Average tolerance | 17.3 ± 5.8* | 16.5 ± 4.4** | 39.9 ± 9.4 | 41.7 ± 11 |

| Average VAS pain (0 – 100) | 43.6 ± 24* | 42.8 ± 25** | 0.88 ± 1.4 | 0.93 ± 2.0 |

All variables are presented as average ± s.d. The anchor scores for each pain index are displayed to the right of the variable, if available. FM: fibromyalgia; CON: control; BL: baseline day; WM: working memory day; MPQ: McGill Pain Questionnaire; FIQ: Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire; BPI: Brief Pain Inventory. Note that VAS measures are taken during the PET scans

indicates significant difference from control subjects during the baseline scan day (p < 0.05)

indicates significant difference from control subjects during the working memory scan day (p < 0.05)

Cognitive Performance

Cognitive task results are presented in Online Resource 2. Relative to controls, FM subjects responded significantly more quickly during the 0-back task. However, there were no significant groups differences in %correct for either the 0-back or the 2-back task. FM subjects had significantly lower scores on the WAIS Digit Span subtest than controls (p < 0.05). There was a trend for FM subjects to have lower scores on the Arithmetic subtest (p = 0.06). All scores were within the normal range of cognitive function.

Group Differences in Baseline FAL BP

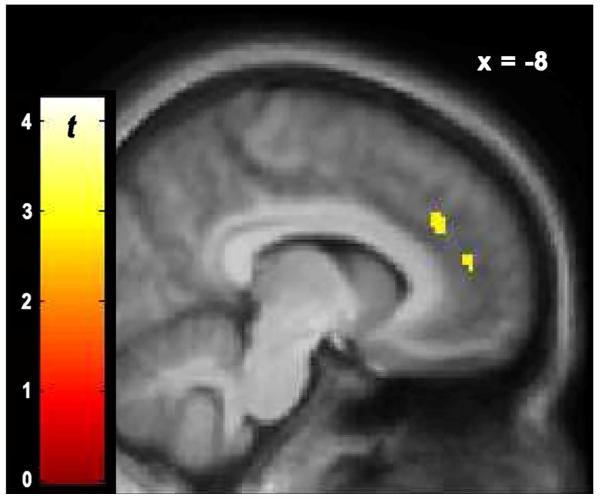

Voxel-wise analyses revealed several cortical regions in which FM FAL BLBP was significantly lower than CON FAL BLBP (Figure 1; Online Resource 3), including the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) and fusiform gyrus. On average, FM BLBP was 29.6% lower than CON BLBP in these regions. There were no regions where FM BLBP was significantly higher than CON BLBP.

Figure 1.

Voxel-wise results from the CON BLBP > FM BLBP full factorial model contrast. Display threshold is p < 0.005, k > 10.

Effects of Working Memory Task on FAL BP

The working memory task did not induce any detectable changes in DA transmission as measured by FAL PET imaging. Across all subjects, there were no main effects of working memory task on FAL BPND (p > 0.005, uncorrected; k > 10).

Baseline FAL BP is Negatively Associated with Current Subjective Pain in FM

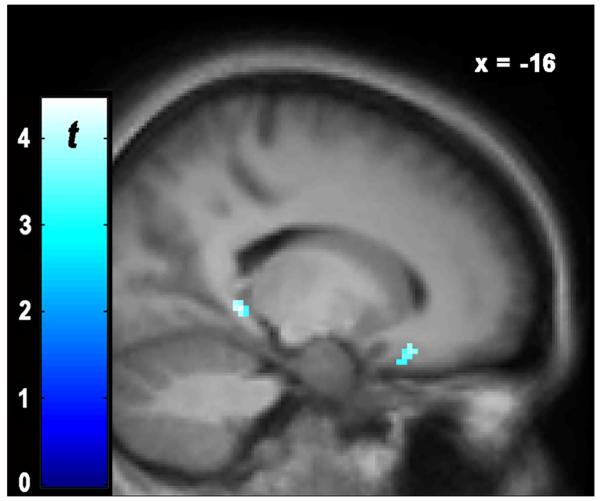

Results from the voxel-wise multiple linear regression indicated that, in FM subjects, FAL BLBP was significantly negatively associated with average BL VAS pain ratings (Figure 2, Online Resource 4). FAL BLBP in the left orbitofrontal cortex and parahippocampal gyrus was significantly negatively correlated with VAS pain during BL scanning.

Figure 2.

Voxel-wise results from the linear regression between baseline VAS pain and baseline FAL BP. Display threshold is p < 0.005, k > 10.

Baseline FAL BP is Negatively Associated with Experimental Pain – FM and CON

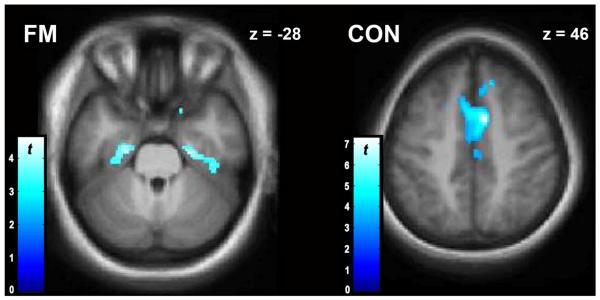

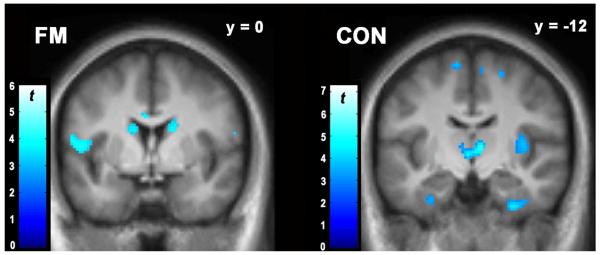

Sensitivity and tolerance to experimentally-induced pressure pain was significantly negatively correlated with FAL BLBP in several brain regions for both FM and CON subjects. In FM, the largest anatomic extent of the correlation between FAL BLBP and average sensitivity (onset of pain perception) was in bilateral parahippocampal gyrus, whereas in CON, the largest clusters were found in the cingulate gyrus and amygdala (Figure 3; see Online Resource 5 for a complete listing of regions with significant correlations). Pain tolerance in FM subjects was negatively related to FAL BLBP in hippocampus, ACC, bilateral striatum, and inferior frontal gyrus (IFG; Figure 4; see Online Resource 6 for a list of significant regions; see Online Resource 7 for a graphical representation in a selected region). Similarly, CON subjects also had negative correlations between tolerance and BLBP in the ACC and IFG, as well as in the thalamus and insula (Figure 4; Online Resources 6 and 7).

Figure 3.

Voxel-wise results from the linear regression between FAL BLBP and average algometry sensitivity in FM (left) and CON (right) subjects. Display threshold is p < 0.005, k < 10. For each group, slice selection was chosen to illustrate results from the largest cluster extent (see Online Resource 5).

Figure 4.

Voxel-wise results from the linear regression between FAL BLBP and average algometry tolerance in FM (left) and CON (right) subjects. Display threshold is p < 0.005, k < 10. For each group, slice selection was chosen to illustrate results from the largest cluster extent (see Online Resources 6 and 7).

DISCUSSION

The principle finding from this pilot dataset is that extrastriatal dopamine (DA) transmission may be altered in fibromyalgia (FM). We found that FM subjects have lower cortical dopamine (DA) D2/D3 receptor binding availability relative to healthy controls. We also provide novel evidence that subjective rating of spontaneous pain in FM is negatively correlated with FAL BP in several brain regions. Finally, we show that sensitivity and tolerance to experimentally evoked pain is associated with baseline D2/D3 receptor availability. To our knowledge, this is the first demonstration that individuals with FM may have aberrant cortical DA function.

Our finding that FM subjects have lower baseline cortical DA receptor binding builds on existing evidence of differing striatal DA receptor binding in chronic pain populations (Cervenka et al. 2006; Hagelberg et al. 2003a; Hagelberg et al. 2003b; Wood et al. 2009; Wood et al. 2007). The present study revealed several cortical regions in which D2/D3 BP is lower in individuals with FM relative to healthy controls (Figure 1, Online Resource 3). Importantly, we detected effects in the ACC. This area is thought to be involved in the processing and regulation of emotional and affective components of pain (Lamm et al. 2011; Etkin et al. 2011). This has implications for chronic pain syndromes like FM, which have high comorbity of affective dysregulation. The presence of affective disorders in FM could influence both how individuals experience pain (Clauw 2009; van Middendorp et al. 2010) and how they self-report pain intensity (Johnson et al. 2010). Our data are consistent with the possibility that aberrant DA transmission within the ACC could potentially be associated with emotional disturbances and enhanced pain perception in FM. Somewhat less expectedly, we observed group differences in FAL BLBP in fusiform gyrus. Although the fusiform gyrus is predominantly known for its role in face recognition (Kanwisher et al. 1997), more recent evidence indicates involvement in emotional regulation (Fonville et al. 2014; Harry et al. 2013). More germane to pain, empathy for pain (rather than being in pain oneself) has been shown to activate the fusiform gyrus in healthy controls (Gu et al. 2013; Singer et al. 2004). Taken together, the data suggest that the fusiform gyrus may be an area of interest of future research in FM and other chronic pain disorders.

The relatively lower cortical DA receptor binding in FM subjects reported here could also be relevant for cognitive processing in FM. Complaints of cognitive deficits are common in FM (Glass 2008), although not all reports have detected consistent differences in cognitive performance (Grace et al. 1999; Landro et al. 1997; Suhr 2003). Anterior cingulate regions are known to be involved with brain networks relevant for memory and perceptual function, including the default mode, executive, and cortical salience networks (Greicius et al. 2003; Seeley et al. 2007). Additionally, proper function of the ACC during cognition involves DA transmission (Aalto et al. 2005; Kodama et al. 2014). Taken together, it is perhaps not surprising that we detected differences in D2/D3 receptor binding in the ACC between FM subjects and controls. Subsequent work is necessary to further understand how cingulate DA transmission contributes to cognitive complaints in chronic pain syndromes.

We also observed that, in FM subjects, there were negative correlations between subjective spontaneous pain ratings during baseline scanning and FAL BLBP in OFC and parahippocampal gyrus (Figure 2; Online Resource 4). To the best of our knowledge, the current report represents the first evidence of a relationship between DA receptor availability and spontaneously-occurring pain in a chronic pain population. It may not be intuitively obvious that a relationship was observed between FAL BLBP and spontaneous pain in the OFC (known more for its role in stimulus valuation (Seymour and McClure 2008)) instead of established central pain nodes such as insula or S1. However, results from a recent fMRI study indicate that OFC activation during pain perception may encode relative pain valuation rather than pain intensity (Winston et al. 2014). Thus, it is possible that DAergic activity in FM is more related to assigning contextual value of pain rather than to the actual interoceptive signaling, raising the possibility that a dysregulation of pain valuation may underlie FM symptoms. Similarly, the parahippocampal gyrus is not typically included in discussions of traditional pain pathways (Apkarian et al. 2005). However, it is thought to be involved in the emotional regulation of pain and pain-related unpleasant stimuli (Fallon 2013; Forkmann et al. 2013; Gosselin et al. 2006; Ploghaus et al. 2001; Stancak et al. 2013). Taken together, the data suggest that dopaminergic activity in the OFC and parahippocampal gyrus may be linked with the experience of spontaneous pain in individuals with FM.

Our final observations were correlations between experimentally administered pressure pain and FAL BLBP in both FM and CON groups (Figures 3 and 4, Online Resources 5, 6, and 7). In FM subjects, we observed a significantly negative association between pain tolerance and dorsal caudate FAL BLBP (Figure 4), which replicates previous findings in both healthy controls and chronic pain patients (Martikainen et al. 2005; Scott et al. 2006; Martikainen et al. 2015). However, we did not find a similar correlation in the caudate of our healthy control sample, which may be due to differences in group characteristics (see below). Of note, Martikainen et al. (2015) also reported a significant negative correlation in chronic pain subjects but not healthy controls.

Of additional interest are the distinct anatomic patterns of the correlations between FAL BLBP and pain sensitivity and tolerance between groups. In CON subjects, FAL BLBP was mainly associated with pain sensitivity and tolerance in regions whose function is thought to be primarily nociceptive, e.g. cingulate, thalamus, insula, and precentral gyrus (Figures 3 and 4; Online Resources 5, 6, and 7; Apkarian et al. 2005; Tracey 2008). However, in FM subjects, FAL BLBP was associated with pain sensitivity and tolerance in regions more involved in emotional and stress regulation, e.g. parahippocampal gyrus, temporal pole, and hippocampus (Forkmann et al. 2013; Mutso et al. 2012; Olson et al. 2007; Ploghaus et al. 2001). This spatial discrepancy is consistent with previous studies that have shown that individuals with FM exhibit markedly different patterns of brain activation and connectivity in response to pain than healthy controls (Gracely et al. 2002; Kim et al. 2015; Loggia et al. 2014; Jensen et al. 2012). Taken together, the evidence suggests that differential DA function in FM patients may contirbute to the perception of chronic pain in this disorder.

We did not detect significant changes in DA transmission during performance of a working memory task, whereas a previous study reported DA release in healthy controls during 2-back performance (Aalto et al. 2005). It is possible that differences in task presentation, duration of task, and response requirements could account for the apparent discrepant results between the respective samples.

There are several limitations to the current study. The sample size is relatively small (although not uncommon for neuroligand PET studies), which introduces the risk of both Type I and II errors. We acknowledge that this is a preliminary analysis, and replication in a larger cohort will be necessary to substantiate our results. However, our findings are generally consistent with previous work, lending credence to our interpretation. Specifically, group differences in baseline FAL BP in the ACC are in line with evidence that these regions are associated with chronic pain pathologies (Baliki et al. 2006; Luerding et al. 2008). Additionally, as mentioned above, significant negative correlations between striatal FAL BLBP and experimental pain tolerance was observed both here and in previously published work (Martikainen et al. 2005; Martikainen et al. 2015; Scott et al. 2006).

Another potential concern in the current study is that we did not replicate the group differences in striatal D2/D3 receptor binding in previous studies of FM (Wood et al. 2007) and related chronic pain disorders (Cervenka et al. 2006; Hagelberg et al. 2003a; Hagelberg et al. 2003b; Martikainen et al. 2005; Pertovaara et al. 2004; Martikainen et al. 2015). One potential explanation for this apparent discrepancy is that the population samples across these studies had different pain disorders. As indicated previously, the various pain syndromes may not have equivalent neurochemical profiles. Additionally, the previous studies excluded for psychiatric disorders, which, while reducing variance within the sample, may select for individuals whose pathology is different from the clinical average (Clauw 2009). In our study, we did not exclude FM subjects with past or present affective disorders (e.g. depression, generalized anxiety disorder). Therefore, our results may be a function of a sample that is more phenotypically representative of this chronic pain population. We also acknowledge that the use of different D2/D3 radioligands across studies could lead to discrepant results.

There are two additional limitations that warrant mention. First, some of our FM subjects were taking medication specifically indicated for FM (e.g., pregabalin). Although there are no known associations between these medications and FAL BLBP, we were unable to match the control sample for these medications, which could be a potential confound. Second, we elected to use an “attentional baseline” scan, which does not allow comparison of the FAL WMBP from our N-back challenge with a “true” resting baseline (wherein the subject does not perform a task). Instead, we elected to control for motor activation and attentional processing with the 0-back task. Although obtaining a third, resting scan would have been the ideal study design, the cost of a third FAL scan was prohibitive for this pilot study.

In conclusion, the present work is the first to investigate extrastriatal D2/D3 receptor availability in individuals with FM. We provide evidence of: 1) differences in baseline FAL BP between FM and CON groups, 2) negative associations between D2/D3 availability and spontaneous pain FM subjects, and 3) negative correlations between D2/D3 availability and pain sensitivity and tolerance, with anatomical differences in these relationships between FM and CON. The results herein demonstrate the utility of [18F]fallypride PET for characterization of putative dysfunction in the DA circuitry of fibromyalgia subjects and othe chronic pain disorders.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by the R03DA024774 (KKY). The authors thank Christine Herring, Lauren Federici, and James Walters for assistance with data collection; Kevin Perry for acquisition of PET data; Michele Beal and Courtney Robbins for assistance with MR scanning; and Dr. Bruce Mock, Dr. Clive Brown-Proctor, Dr. Qi-Huang Zheng, Barbara Glick-Wilson, and Brandon Steele for [18F]fallypride synthesis. Dr. Brenna McDonald provided consultation for scoring and interpretation of the neuropsychological assessments and working memory task.

Funding: This study was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse R03DA024774 (KKY).

Footnotes

COMPLIANCE WITH ETHICAL STANDARDS

Conflict of Interest: D.S. Albrecht, P.J. MacKie, D.A. Kareken, G.D. Hutchins, E.J. Chumin, B.T. Christian, and K.K. Yoder declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Informed Consent: All study procedures were approved by the Indiana University Institutional Review Board, and as such, were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Belmont Report (1974; National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research). Written informed consent was obtained from all patients prior to participation in the study.

REFERENCES

- Aalto S, Bruck A, Laine M, Nagren K, Rinne JO. Frontal and temporal dopamine release during working memory and attention tasks in healthy humans: a positron emission tomography study using the high-affinity dopamine D2 receptor ligand [11C]FLB 457. J Neurosci. 2005;25(10):2471–2477. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2097-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albrecht DS, Kareken DA, Christian BT, Dzemidzic M, Yoder KK. Cortical dopamine release during a behavioral response inhibition task. Synapse. 2014;68(6):266–274. doi: 10.1002/syn.21736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apkarian AV, Baliki MN, Geha PY. Towards a theory of chronic pain. Prog Neurobiol. 2009;87(2):81–97. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2008.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apkarian AV, Bushnell MC, Treede RD, Zubieta JK. Human brain mechanisms of pain perception and regulation in health and disease. Eur J Pain. 2005;9(4):463–484. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asmundson GJ, Katz J. Understanding the co-occurrence of anxiety disorders and chronic pain: state-of-the-art. Depress Anxiety. 2009;26(10):888–901. doi: 10.1002/da.20600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baliki MN, Chialvo DR, Geha PY, Levy RM, Harden RN, Parrish TB, et al. Chronic pain and the emotional brain: specific brain activity associated with spontaneous fluctuations of intensity of chronic back pain. J Neurosci. 2006;26(47):12165–12173. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3576-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballantyne JC, Shin NS. Efficacy of opioids for chronic pain: a review of the evidence. Clin J Pain. 2008;24(6):469–478. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e31816b2f26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961;4:561–571. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berryman C, Stanton TR, Jane Bowering K, Tabor A, McFarlane A, Lorimer Moseley G. Evidence for working memory deficits in chronic pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pain. 2013;154(8):1181–1196. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2013.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burckhardt CS, Clark SR, Bennett RM. The fibromyalgia impact questionnaire: development and validation. J Rheumatol. 1991;18(5):728–733. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cervenka S, Palhagen SE, Comley RA, Panagiotidis G, Cselenyi Z, Matthews JC, et al. Support for dopaminergic hypoactivity in restless legs syndrome: a PET study on D2-receptor binding. Brain. 2006;129(Pt 8):2017–2028. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christian BT, Lehrer DS, Shi B, Narayanan TK, Strohmeyer PS, Buchsbaum MS, et al. Measuring dopamine neuromodulation in the thalamus: using [F-18]fallypride PET to study dopamine release during a spatial attention task. Neuroimage. 2006;31(1):139–152. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.11.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clauw DJ. Fibromyalgia: an overview. Am J Med. 2009;122(12 Suppl):S3–S13. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleeland CS, Ryan KM. Pain assessment: global use of the Brief Pain Inventory. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 1994;23(2):129–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costes N, Merlet I, Ostrowsky K, Faillenot I, Lavenne F, Zimmer L, et al. A 18F-MPPF PET normative database of 5-HT1A receptor binding in men and women over aging. J Nucl Med. 2005;46(12):1980–1989. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etkin A, Egner T, Kalisch R. Emotional processing in anterior cingulate and medial prefrontal cortex. Trends Cogn Sci. 2011;15(2):85–93. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2010.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fallon N. Structural and functional brain alterations in fibromyalgia syndrome patients. University of Liverpool; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Fonville L, Giampietro V, Surguladze S, Williams S, Tchanturia K. Increased BOLD signal in the fusiform gyrus during implicit emotion processing in anorexia nervosa. Neuroimage Clin. 2014;4:266–273. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2013.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forkmann K, Wiech K, Ritter C, Sommer T, Rose M, Bingel U. Pain-specific modulation of hippocampal activity and functional connectivity during visual encoding. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2013;33(6):2571–2581. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2994-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao M, Wang M, Mock BH, Glick-Wilson BE, Yoder KK, Hutchins GD, et al. An improved synthesis of dopamine D2/D3 receptor radioligands [11C]fallypride and [18F]fallypride. Appl Radiat Isot. 2010;68(6):1079–1086. doi: 10.1016/j.apradiso.2009.09.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass JM. Fibromyalgia and cognition. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(Suppl 2):20–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gosselin N, Samson S, Adolphs R, Noulhiane M, Roy M, Hasboun D, et al. Emotional responses to unpleasant music correlates with damage to the parahippocampal cortex. Brain. 2006;129(Pt 10):2585–2592. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grace GM, Nielson WR, Hopkins M, Berg MA. Concentration and memory deficits in patients with fibromyalgia syndrome. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 1999;21(4):477–487. doi: 10.1076/jcen.21.4.477.876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gracely RH, Petzke F, Wolf JM, Clauw DJ. Functional magnetic resonance imaging evidence of augmented pain processing in fibromyalgia. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46(5):1333–1343. doi: 10.1002/art.10225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greicius MD, Krasnow B, Reiss AL, Menon V. Functional connectivity in the resting brain: a network analysis of the default mode hypothesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(1):253–258. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0135058100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gronwall D. Paced auditory serial-addition task: a measure of recovery from concussion. Perceptual and motor skills. 1977;44(2):367–373. doi: 10.2466/pms.1977.44.2.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu X, Hof PR, Friston KJ, Fan J. Anterior insular cortex and emotional awareness. J Comp Neurol. 2013;521(15):3371–3388. doi: 10.1002/cne.23368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gureje O. Psychiatric aspects of pain. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2007;20(1):42–46. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e328010ddf4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagelberg N, Forssell H, Aalto S, Rinne JO, Scheinin H, Taiminen T, et al. Altered dopamine D2 receptor binding in atypical facial pain. Pain. 2003a;106(1-2):43–48. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(03)00275-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagelberg N, Forssell H, Rinne JO, Scheinin H, Taiminen T, Aalto S, et al. Striatal dopamine D1 and D2 receptors in burning mouth syndrome. Pain. 2003b;101(1-2):149–154. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(02)00323-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagelberg N, Martikainen IK, Mansikka H, Hinkka S, Nagren K, Hietala J, et al. Dopamine D2 receptor binding in the human brain is associated with the response to painful stimulation and pain modulatory capacity. Pain. 2002;99(1-2):273–279. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(02)00121-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harry B, Williams MA, Davis C, Kim J. Emotional expressions evoke a differential response in the fusiform face area. Front Hum Neurosci. 2013;7:692. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2013.00692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Innis RB, Cunningham VJ, Delforge J, Fujita M, Gjedde A, Gunn RN, et al. Consensus nomenclature for in vivo imaging of reversibly binding radioligands. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2007;27(9):1533–1539. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen KB, Loitoile R, Kosek E, Petzke F, Carville S, Fransson P, et al. Patients with fibromyalgia display less functional connectivity in the brain's pain inhibitory network. Mol Pain. 2012;8:32. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-8-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johannes CB, Le TK, Zhou X, Johnston JA, Dworkin RH. The prevalence of chronic pain in United States adults: results of an Internet-based survey. J Pain. 2010;11(11):1230–1239. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2010.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson AL, Storzbach D, Binder LM, Barkhuizen A, Kent Anger W, Salinsky MC, et al. MMPI-2 profiles: fibromyalgia patients compared to epileptic and non-epileptic seizure patients. Clin Neuropsychol. 2010;24(2):220–234. doi: 10.1080/13854040903266902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanwisher N, McDermott J, Chun MM. The fusiform face area: a module in human extrastriate cortex specialized for face perception. J Neurosci. 1997;17(11):4302–4311. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-11-04302.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Loggia ML, Cahalan CM, Harris RE, Beissner F, Garcia RG, et al. The somatosensory link in fibromyalgia: functional connectivity of the primary somatosensory cortex is altered by sustained pain and is associated with clinical/autonomic dysfunction. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015;67(5):1395–1405. doi: 10.1002/art.39043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kodama T, Hikosaka K, Honda Y, Kojima T, Watanabe M. Higher dopamine release induced by less rather than more preferred reward during a working memory task in the primate prefrontal cortex. Behav Brain Res. 2014;266:104–107. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2014.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuijpers T, van Middelkoop M, Rubinstein S, Ostelo R, Verhagen A, Koes B, et al. A systematic review on the effectiveness of pharmacological interventions for chronic non-specific low-back pain. European Spine Journal. 2011;20(1):40–50. doi: 10.1007/s00586-010-1541-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamm C, Decety J, Singer T. Meta-analytic evidence for common and distinct neural networks associated with directly experienced pain and empathy for pain. Neuroimage. 2011;54(3):2492–2502. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landro NI, Stiles TC, Sletvold H. Memory functioning in patients with primary fibromyalgia and major depression and healthy controls. J Psychosom Res. 1997;42(3):297–306. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(96)00301-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logan J, Fowler JS, Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Ding YS, Alexoff DL. Distribution volume ratios without blood sampling from graphical analysis of PET data. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1996;16(5):834–840. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199609000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loggia ML, Berna C, Kim J, Cahalan CM, Gollub RL, Wasan AD, et al. Disrupted brain circuitry for pain-related reward/punishment in fibromyalgia. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66(1):203–212. doi: 10.1002/art.38191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luerding R, Weigand T, Bogdahn U, Schmidt-Wilcke T. Working memory performance is correlated with local brain morphology in the medial frontal and anterior cingulate cortex in fibromyalgia patients: structural correlates of pain-cognition interaction. Brain. 2008;131(Pt 12):3222–3231. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martikainen IK, Hagelberg N, Mansikka H, Hietala J, Nagren K, Scheinin H, et al. Association of striatal dopamine D2/D3 receptor binding potential with pain but not tactile sensitivity or placebo analgesia. Neurosci Lett. 2005;376(3):149–153. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2004.11.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martikainen IK, Nuechterlein EB, Pecina M, Love TM, Cummiford CM, Green CR, et al. Chronic Back Pain Is Associated with Alterations in Dopamine Neurotransmission in the Ventral Striatum. J Neurosci. 2015;35(27):9957–9965. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4605-14.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCracken LM, Iverson GL. Predicting complaints of impaired cognitive functioning in patients with chronic pain. Journal of pain and symptom management. 2001;21(5):392–396. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(01)00267-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald BC, Conroy SK, Ahles TA, West JD, Saykin AJ. Alterations in brain activation during working memory processing associated with breast cancer and treatment: a prospective functional magnetic resonance imaging study. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(20):2500–2508. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.5674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melzack R. The short-form McGill Pain Questionnaire. Pain. 1987;30(2):191–197. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(87)91074-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mutso AA, Radzicki D, Baliki MN, Huang L, Banisadr G, Centeno MV, et al. Abnormalities in hippocampal functioning with persistent pain. J Neurosci. 2012;32(17):5747–5756. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0587-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieoullon A. Dopamine and the regulation of cognition and attention. Prog Neurobiol. 2002;67(1):53–83. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(02)00011-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldfield RC. The assessment and analysis of handedness: the Edinburgh inventory. Neuropsychologia. 1971;9(1):97–113. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(71)90067-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson IR, Plotzker A, Ezzyat Y. The Enigmatic temporal pole: a review of findings on social and emotional processing. Brain. 2007;130(Pt 7):1718–1731. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pertovaara A, Martikainen IK, Hagelberg N, Mansikka H, Nagren K, Hietala J, et al. Striatal dopamine D2/D3 receptor availability correlates with individual response characteristics to pain. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;20(6):1587–1592. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03622.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picard F, Bruel D, Servent D, Saba W, Fruchart-Gaillard C, Schollhorn-Peyronneau MA, et al. Alteration of the in vivo nicotinic receptor density in ADNFLE patients: a PET study. Brain. 2006;129(Pt 8):2047–2060. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ploghaus A, Narain C, Beckmann CF, Clare S, Bantick S, Wise R, et al. Exacerbation of pain by anxiety is associated with activity in a hippocampal network. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2001;21(24):9896–9903. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-24-09896.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pomerleau CS, Carton SM, Lutzke ML, Flessland KA, Pomerleau OF. Reliability of the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire and the Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence. Addict Behav. 1994;19(1):33–39. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(94)90049-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott DJ, Heitzeg MM, Koeppe RA, Stohler CS, Zubieta JK. Variations in the human pain stress experience mediated by ventral and dorsal basal ganglia dopamine activity. J Neurosci. 2006;26(42):10789–10795. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2577-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeley WW, Menon V, Schatzberg AF, Keller J, Glover GH, Kenna H, et al. Dissociable intrinsic connectivity networks for salience processing and executive control. J Neurosci. 2007;27(9):2349–2356. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5587-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo J, Kim SH, Kim YT, Song HJ, Lee JJ, Han SW, et al. Working memory impairment in fibromyalgia patients associated with altered frontoparietal memory network. PLoS One. 2012;7(6):e37808. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seymour B, McClure SM. Anchors, scales and the relative coding of value in the brain. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2008;18(2):173–178. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2008.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer T, Seymour B, O'Doherty J, Kaube H, Dolan RJ, Frith CD. Empathy for pain involves the affective but not sensory components of pain. Science. 2004;303(5661):1157–1162. doi: 10.1126/science.1093535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell MB, Sobell LC, Klajner F, Pavan D, Basian E. The reliability of a timeline method for assessing normal drinker college students' recent drinking history: utility for alcohol research. Addict Behav. 1986;11(2):149–161. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(86)90040-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger CD. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) Consulting Psychologists Press; Palo Alta, CA: 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Stancak A, Ward H, Fallon N. Modulation of pain by emotional sounds: A laser - evoked potential study. European Journal of Pain. 2013;17(3):324–335. doi: 10.1002/j.1532-2149.2012.00206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suhr JA. Neuropsychological impairment in fibromyalgia: relation to depression, fatigue, and pain. J Psychosom Res. 2003;55(4):321–329. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00628-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tracey I. Imaging pain. Br J Anaesth. 2008;101(1):32–39. doi: 10.1093/bja/aen102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Middendorp H, Lumley MA, Moerbeek M, Jacobs JW, Bijlsma JW, Geenen R. Effects of anger and anger regulation styles on pain in daily life of women with fibromyalgia: a diary study. Eur J Pain. 2010;14(2):176–182. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2009.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: the PANAS scales. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1988;54(6):1063–1070. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.54.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale. 3rd ed The Pscyhological Corporation; San Antonio, TX: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Williams DA, Clauw DJ, Glass JM. Perceived cognitive dysfunction in fibromyalgia syndrome. Journal of Musculoskeletal Pain. 2011;19(2):66–75. [Google Scholar]

- Winston JS, Vlaev I, Seymour B, Chater N, Dolan RJ. Relative valuation of pain in human orbitofrontal cortex. J Neurosci. 2014;34(44):14526–14535. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1706-14.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe F, Smythe HA, Yunus MB, Bennett RM, Bombardier C, Goldenberg DL, et al. The American College of Rheumatology 1990 criteria for the classification of fibromyalgia. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 1990;33(2):160–172. doi: 10.1002/art.1780330203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood PB, Glabus MF, Simpson R, Patterson JC., 2nd Changes in gray matter density in fibromyalgia: correlation with dopamine metabolism. J Pain. 2009;10(6):609–618. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2008.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood PB, Schweinhardt P, Jaeger E, Dagher A, Hakyemez H, Rabiner EA, et al. Fibromyalgia patients show an abnormal dopamine response to pain. Eur J Neurosci. 2007;25(12):3576–3582. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05623.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziolko SK, Weissfeld LA, Klunk WE, Mathis CA, Hoge JA, Lopresti BJ, et al. Evaluation of voxel-based methods for the statistical analysis of PIB PET amyloid imaging studies in Alzheimer's disease. Neuroimage. 2006;33(1):94–102. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.05.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.