Abstract

BACKGROUND

Persons with bipolar disorders represent a high risk group for obesity, but little is known about the time course by which weight gain occurs in bipolar disorder.

METHODS

We prospectively studied changes in fat distribution using dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry in relationship to medication exposure and mood symptom burden in thirty-six participants with bipolar disorders. We assessed the relationship between prior medication exposure and course of illness with adiposity measures at baseline in the full sample and at 6-month follow-up in 22 individuals.

RESULTS

At baseline, greater adiposity was associated with only advanced age and female sex, not retrospectively assessed symptom course or medication exposure (past two years). Over six months of prospective follow-up, participants developed greater adiposity (fat mass index +0.82 kg/m2, p=0.007; visceral fat area +8.6 cm2, p=0.02; total percent fat +1.6%, p=0.02). Manic symptomatology, not antipsychotic exposure, was related to the increased adiposity.

CONCLUSIONS

Acute exacerbations of mood disorders appear to represent high risk periods for adipose deposition. Obesity prevention efforts may be necessary during acute exacerbations.

Keywords: Bipolar disorder, adiposity, absorptiometry, DXA, prospective cohort study

INTRODUCTION

Individuals with bipolar disorder are at greater risk of obesity, likely due to illness-influenced behaviors, mood-induced physiological changes, and pharmacotherapy (1–3). Antipsychotics, in particular, produce considerable weight gain, which may worsen cardiometabolic risk factors, especially if weight gain is rapid (4,5). Beyond treatment, course of illness may impact risk as those with more prior mood episodes demonstrate greater changes in weight (6).

The morbidity and mortality related to weight is largely a function of fat mass (7). Fat mass index (FMI) is the total fat mass divided by the height squared (kg/m2), a height-adjusted measure of overall adiposity akin to body mass index (BMI). Because FMI excludes lean mass, it more accurately measures adiposity than total body weight or BMI and is thus a more relevant indicator of human health (7). Thus, we conducted a prospective study to examine changes in adiposity following the onset of antipsychotic treatment in patients with bipolar disorder. We hypothesized that both antipsychotic exposure and the persistence of mood symptoms would be associated with increased adiposity.

METHODS

Sample

We recruited 36 individuals between the ages of 18 and 50 with bipolar or a related mood disorder (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-IV-defined bipolar I; bipolar II; bipolar not otherwise specified; schizoaffective disorder; major depressive disorder with psychotic features) (8) between 9/2007 and 4/2013. Recruitment was conducted through clinician referral, advertisement (posters and brochures), targeted mailings, electronic mail, and identification of potentially eligible participants through the electronic medical record. We excluded participants with neoplasm, untreated thyroid disease, pregnancy or planned pregnancy, or active substance abuse. We also excluded those who started antipsychotics, valproic acid derivatives, or lipid-lowering agents in the preceding three months. Incident users of antipsychotics were selectively recruited and baseline assessments performed within 96 hours of first antipsychotic dose. We also recruited individuals with a similar likelihood of starting antipsychotics, by using a locally-derived propensity score, based predominantly on illness severity (age, mania, psychosis, married status, lithium use) (9), and these participants could be later started on antipsychotics. All participants provided written informed consent under the auspices of the University of Iowa Institutional Review Board.

Exposure Assessment

A psychiatrist (JGF) confirmed the psychiatric diagnosis by clinical interview. Clinical characteristics, including age of onset, duration of illness, number of hospitalizations related to the illness, and the burden of depression and mania over the past decade were ascertained by direct questioning using previously-reported methods (10). Age of onset could not be estimated for two participants and retrospective symptom burden measures were not obtained for nine. Medication histories were obtained for the previous two years and medication exposure was tracked over follow-up. Medications were grouped in broad medication classes using prior methods: first generation antipsychotics, second generation antipsychotics, valproic acid derivatives, lithium, carbamazepine, tricyclic antidepressants, monoamine oxidase inhibitors, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, other antidepressants, and benzodiazepines (11–13). Exposure to tobacco (pack-years) was also ascertained by direct interview.

Of the 36 participants, 22 (61%) completed the six month follow-up. Fifteen were incident users of an antipsychotic medication at intake and 7 were non-antipsychotic users with similar illness severity. Depressive and manic symptomatology were assessed using the clinician-administered Montgomery Asberg Depression Rating Scale (14) and the Young Mania Rating Scale (15). The baseline, three-, and six-month scores were averaged to estimate depressive and manic symptom burden over follow-up. Medication use and self-reported adherence were assessed at each follow-up visit with exposure categorized by the total number of weeks taking each of the aforementioned medication groupings.

Absorptiometry

Body fat distribution was assessed using dual energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) at baseline and six months using a Hologic Discovery A unit (Hologic Inc., Bedford, MA). The software package APEX 4.0.1/13.4.1 generated advanced body composition reports for our a priori primary outcome measure of interest, FMI (kg/m2) and for our secondary outcomes, visceral fat area and total percent fat. Visceral fat area estimated by APEX 4.0.1/13.4.1 represents the cross-sectional area (cm2) of fat inside the abdominal cavity and has been validated against computed tomography (16). BMI was examined for comparison to other studies.

Statistical Analyses

SAS 9.4 was used for analyses (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). DXA outcomes were modeled as dependent variables in multivariate linear regression analysis with baseline values compared to duration of illness or retrospectively estimated 10-year symptom burden (or since illness onset) and two year medication exposure. All models controlled for age and gender. Changes in adiposity indices over six months were made via paired t-tests. Contrasts were made between incident users of antipsychotics and comparison subjects of similar propensity-score. Because antipsychotic and other medication use varied across recruitment groups, cumulative exposure to medications, rather than group, and mood symptom burden over the six months were assessed in relation to adiposity outcomes using analogous linear regression models.

RESULTS

Sample characteristics are shown in Table 1. Clinical indices were consistent with severe illness with the vast majority (89%) previously or currently hospitalized for a psychiatric disorder, and nearly one-third (31%) with a prior suicide attempt.

Table 1.

Baseline Sociodemographic and clinical Characteristics of Sample (N=36).

| N (%) | |

|---|---|

| Male Gender | 27 (75%) |

| Marital Status | |

| Single | 22 (61%) |

| Married | 8 (22%) |

| Divorced/Separated | 5 (14%) |

| Widowed | 1 (3%) |

| Race | |

| White | 29 (81%) |

| Black | 3 (8%) |

| Native American | 4 (11%) |

| Unemployed | 10 (28%) |

| Smokers | |

| Current | 23 (64%) |

| Former | 3 (8%) |

| Never | 10 (28%) |

| Primary Diagnosis | |

| Bipolar I | 18 (50%) |

| Bipolar II | 6 (17%) |

| Schizoaffective disorder | 6 (17%) |

| Other | 6 (17%) |

| History of alcohol abuse/dependence | 17 (47%) |

| History of drug abuse/dependence | 14 (39%) |

| History of Psychiatric Hospitalization | 32 (89%) |

| History of Suicide Attempt | 11 (31%) |

| Medications, past year | |

| Antihypertensive | 2 (6%) |

| Diabetes treatment | 0 |

| Lipid lowering medication | 1 (3%) |

| Inhaled steroid | 3 (9%) |

| Psychotropic Medications, any use past 2 years | |

| Antipsychotic | 11 (31%) |

| First-generation | 1 (3%) |

| Second-generation | 10 (28%) |

| Antidepressant | 23 (64%) |

| Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor | 13 (36%) |

| Tricyclic | 1 (3%) |

| Other Antidepressant | 9 (25%) |

| Anticonvulsant / Mood stabilizer | 16 (44%) |

| Lithium | 12 (33%) |

| Lamotrigine | 6 (17%) |

| Valproic acid derivative | 1 (3%) |

| Carbamazepine | 1 (3%) |

| Benzodiazepine | 5 (14%) |

| Mean (SD) | |

| Age, years | 30.2 (9.7) |

| Education, years | 13.8 (2.3) |

| Duration of Mood Disorder, years (N=34) | 9.5 (7.4) |

| Smoking pack*years (N=26) | 10.3 (12.1) |

| Montgomery Asberg Depression Rating Scale | 19.1 (12.9) |

| Young Mania Rating Scale | 11.2 (13.0) |

| Body Mass Index (kg/m2) | 26.2 (4.7) |

| Fat Mass Index (kg/m2) | 7.8 (3.0) |

| Total Percent Fat (%) | 28.7 (7.9) |

| Visceral Fat Area (cm2) | 90.4 (45.2) |

In models controlling for age and gender, there was no relationship between estimated duration of the mood disorder and adiposity measures at baseline (FMI (p=0.97), total percent fat (p=0.36), visceral fat area (p=0.78)); although, as expected, increasing age (p=0.03, p=0.005, p=0.001 respectively) and female sex (p=0.12, p=0.001, p=0.01 respectively) were assocated with greater adiposity across measures. BMI was similarly not significantly related to duration of illness (p=0.40). In analogous models, the number of weeks exposed to antipsychotics, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, and lithium were not related to the adiposity measures.

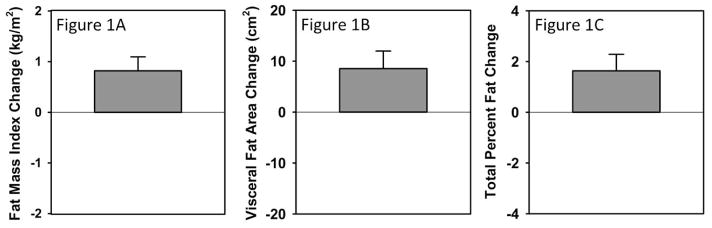

Over the six month follow-up, substantial increases were seen in adiposity measures (FMI increased by 0.82 kg/m2, 95% C.I. 0.25–1.39, t=2.97, df=21, p=0.007; visceral fat area by 8.6 cm2, 95% C.I. 1.4–15.7, t=2.49, df=21, p=0.02; and total percent fat by 1.6%, 95% C.I. 0.3–3.0, t=−2.51, df=21, p=0.02) as shown in Figure 1. In comparision, BMI increased by 0.97 kg/m2 (95% C.I. 0.06–2.04, t=2.22, df=21, p=0.04). Adiposity measures did not significantly differ by incident use of antipychotic at intake although percent fat change was marginally greater amongst incident users of antipsychotics relative to controls (2.2% vs. 0.5%, Wilcoxon Z=1.76, p=0.08). Medication use changed frequently over follow-up and cumulative antipsychotic exposure over the six months of follow-up was not related to FMI (p=0.59), total percent fat (p=0.79), or visceral fat area (p=0.17). Similarly, lithium exposure was unrelated (p=0.52–64). Depressive symptom burden also did not predict change in adiposity measures. In contrast, after adjusting for age and sex, manic symptom burden was significantly associated with FMI (t=2.30, partial R2=0.23, p=0.03) and total percent fat (t=2.21, partial R2= 0.21, p=0.04) but not visceral fat area (t=0.43, partial R2= 0.01, p=0.67). This appeared independent of antipscyhotic and lithium exposure (weeks).

Figure 1. Change in adiposity after six month follow-up (N=22).

After recruitment in acute mood episodes, participants exhibited statistically significant increases in adiposity measures. On average, fat mass index increased by 0.82 kg/m2 (Figure 1A), visceral fat area by 8.6 cm2 (Figure 1B), and total percent fat by 1.6% (Figure 1C).

DISCUSSION

Significant increases in adiposity measures were observed in just six months in individuals symptomatic with bipolar disorder, identifying a high risk group for targeted obesity prevention efforts. This rapid and substantial weight gain was striking although rapid weight change has previously been reported with antipsychotic use (17). In this small sample, however, we could not detect any associations between antipsychotic use and our adiposity measures. We did, however, find an association between the persistence of manic symptomatology and increases in adiposity.

Persistent manic symptomatology may increase adiposity though a variety of mechanisms (18). This adiposity may contribute to the previously reported association between manic symptom burden and endothelial dysfunction (12), arterial stiffness (10), and cardiovascular mortality (13). Adiposity may represent one of several factors contributing to the premature mortality observed in those with a history of mania (19,20) and represents a potentially modifiable risk factor. The magnitude of change in adiposity measures in only six months is striking. Others have reported large increases in weight among those treated with antipsychotic medications (21), and our younger adult sample may have been at greater risk (22). The lack of association with medication in this sample may be due to limited power due to small sample size and with antipsychotic and other medication exposure common across participant groupings. Participants were excluded if they received any antipsychotics in the prior three months, limiting the ability of retrospective analysis to identify antipsychotic-related effects. Retrospective studies of persons with bipolar I have reported weight gain with depression and not during maintenance treatment or mania (23).

Key limitations of this study include the small sample size and observational design. While participants could have been randomized to medications, clinical trials of individuals with acute illness demonstrate that non-adherence and attrition are significant over extended periods in those recruited for acute antipsychotic treatment (24,25), and randomization to symptom burden is impossible. Strengths of the study include the prospective design, use of DXA to assess adiposity and tissue composition, and the use of clinician-administered mood rating scales. Long-term study of larger cohorts may be useful to better characterize and elucidate mechanisms underlying the relationship between mood symptoms and increased adiposity.

CONCLUSIONS

The degree of fat deposition over a six month follow-up is concerning and suggests that similar samples represent a high risk group for targeted obesity prevention efforts. Clinicians would be wise to not defer obesity prevention strategies until periods of greater stability. Early efforts to mitigate risk are warranted, and both behavioral and pharmacological strategies may be efficacious (26,27). Despite limited evidence for specificity to the effects of antipsychotics on weight, pharmacological trials have generally focused on antipsychotic-related weight gain with the most evidence for metformin and topiramate (26).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (K23MH083695, P01HL014388, K23MH085005).

Footnotes

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding agencies.

References

- 1.Shah A, Shen N, El-Mallakh RS. Weight gain occurs after onset of bipolar illness in overweight bipolar patients. Annals of clinical psychiatry : official journal of the American Academy of Clinical Psychiatrists. 2006 Oct-Dec;18(4):239–241. doi: 10.1080/10401230600948423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fiedorowicz JG, Palagummi NM, Forman-Hoffman VL, Miller DD, Haynes WG. Elevated prevalence of obesity, metabolic syndrome, and cardiovascular risk factors in bipolar disorder. Annals of clinical psychiatry : official journal of the American Academy of Clinical Psychiatrists. 2008 Jul-Sep;20(3):131–137. doi: 10.1080/10401230802177722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu CS, Carvalho AF, Mansur RB, McIntyre RS. Obesity and bipolar disorder: synergistic neurotoxic effects? Advances in therapy. 2013 Nov;30(11):987–1006. doi: 10.1007/s12325-013-0067-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gilles M, Hentschel F, Paslakis G, Glahn V, Lederbogen F, Deuschle M. Visceral and subcutaneous fat in patients treated with olanzapine: a case series. Clinical neuropharmacology. 2010 Sep-Oct;33(5):248–249. doi: 10.1097/WNF.0b013e3181f0ec33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Calarge CA, Xie D, Fiedorowicz JG, Burns TL, Haynes WG. Rate of weight gain and cardiometabolic abnormalities in children and adolescents. The Journal of pediatrics. 2012 Dec;161(6):1010–1015. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2012.05.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reininghaus EZ, Lackner N, Fellendorf FT, et al. Weight cycling in bipolar disorder. Journal of affective disorders. 2015 Jan;171:33–38. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heitmann BL, Erikson H, Ellsinger BM, Mikkelsen KL, Larsson B. Mortality associated with body fat, fat-free mass and body mass index among 60-year-old swedish men-a 22-year follow-up. The study of men born in 1913. International journal of obesity and related metabolic disorders : journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity. 2000 Jan;24(1):33–37. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. Text Revision ed. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prabhakar M, Haynes WG, Coryell WH, et al. Factors associated with the prescribing of olanzapine, quetiapine, and risperidone in patients with bipolar and related affective disorders. Pharmacotherapy. 2011 Aug;31(8):806–812. doi: 10.1592/phco.31.8.806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sodhi SK, Linder J, Chenard CA, Miller del D, Haynes WG, Fiedorowicz JG. Evidence for accelerated vascular aging in bipolar disorder. Journal of psychosomatic research. 2012 Sep;73(3):175–179. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2012.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Linder JR, Sodhi SK, Haynes WG, Fiedorowicz JG. Effects of antipsychotic drugs on cardiovascular variability in participants with bipolar disorder. Human psychopharmacology. 2014 Mar;29(2):145–151. doi: 10.1002/hup.2380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fiedorowicz JG, Coryell WH, Rice JP, Warren LL, Haynes WG. Vasculopathy related to manic/hypomanic symptom burden and first-generation antipsychotics in a sub-sample from the collaborative depression study. Psychotherapy and psychosomatics. 2012;81(4):235–243. doi: 10.1159/000334779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fiedorowicz JG, Solomon DA, Endicott J, et al. Manic/hypomanic symptom burden and cardiovascular mortality in bipolar disorder. Psychosomatic medicine. 2009 Jul;71(6):598–606. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181acee26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Montgomery SA, Asberg M. A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. Br J Psychiatry. 1979 Apr;134:382–389. doi: 10.1192/bjp.134.4.382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Young RC, Biggs JT, Ziegler VE, Meyer DA. A rating scale for mania: reliability, validity and sensitivity. Br J Psychiatry. 1978 Nov;133:429–435. doi: 10.1192/bjp.133.5.429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Micklesfield LK, Goedecke JH, Punyanitya M, Wilson KE, Kelly TL. Dual-energy X-ray performs as well as clinical computed tomography for the measurement of visceral fat. Obesity. 2012 May;20(5):1109–1114. doi: 10.1038/oby.2011.367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alvarez-Jimenez M, Gonzalez-Blanch C, Crespo-Facorro B, et al. Antipsychotic-induced weight gain in chronic and first-episode psychotic disorders: a systematic critical reappraisal. CNS drugs. 2008;22(7):547–562. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200822070-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fiedorowicz JG, Linder J, Sodhi SK. The search for mediators of vascular mortality with mania. Revista brasileira de psiquiatria. 2014 Jan-Mar;36(1):98–99. doi: 10.1590/1516-4446-2013-3505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weiner M, Warren L, Fiedorowicz JG. Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in bipolar disorder. Annals of clinical psychiatry : official journal of the American Academy of Clinical Psychiatrists. 2011 Feb;23(1):40–47. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Murray DP, Weiner M, Prabhakar M, Fiedorowicz JG. Mania and mortality: why the excess cardiovascular risk in bipolar disorder? Current psychiatry reports. 2009 Dec;11(6):475–480. doi: 10.1007/s11920-009-0072-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ratzoni G, Gothelf D, Brand-Gothelf A, et al. Weight gain associated with olanzapine and risperidone in adolescent patients: a comparative prospective study. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2002 Mar;41(3):337–343. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200203000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.De Hert M, Detraux J, van Winkel R, Yu W, Correll CU. Metabolic and cardiovascular adverse effects associated with antipsychotic drugs. Nature reviews. Endocrinology. 2012 Feb;8(2):114–126. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2011.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fagiolini A, Frank E, Houck PR, et al. Prevalence of obesity and weight change during treatment in patients with bipolar I disorder. The Journal of clinical psychiatry. 2002 Jun;63(6):528–533. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v63n0611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lieberman JA, Stroup TS, McEvoy JP, et al. Effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs in patients with chronic schizophrenia. The New England journal of medicine. 2005 Sep 22;353(12):1209–1223. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lieberman JA, Tollefson GD, Charles C, et al. Antipsychotic drug effects on brain morphology in first-episode psychosis. Archives of general psychiatry. 2005 Apr;62(4):361–370. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.4.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fiedorowicz JG, Miller DD, Bishop JR, Calarge CA, Ellingrod VL, Haynes WG. Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Pharmacological Interventions for Weight Gain from Antipsychotics and Mood Stabilizers. Current psychiatry reviews. 2012 Feb 1;8(1):25–36. doi: 10.2174/157340012798994867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Green CA, Yarborough BJ, Leo MC, et al. The STRIDE Weight Loss and Lifestyle Intervention for Individuals Taking Antipsychotic Medications: A Randomized Trial. The American journal of psychiatry. 2014 Sep 15; doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.14020173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]