Abstract

The management of paediatric primary vesico-ureteric reflux (VUR) has undergone serial changes over the last decade. As this disorder is extremely heterogeneous, and high-quality prospective data are limited, the treatment strategies vary among centres. Current treatment options include observation only, continuous antibiotic prophylaxis, and surgery. Surgical intervention is indicated if a child has a breakthrough urinary tract infection (UTI) while on continuous antibiotic prophylaxis or if there are renal scars present. After excluding a secondary cause of VUR the physician should consider the risk factors affecting the severity of VUR and manage the child accordingly. Those factors include demographic factors (age at presentation, gender, ethnicity) and clinical factors (VUR grade, unilateral vs. bilateral, presence of renal scars, initial presentation, the number of UTIs, and presence of any voiding or bowel dysfunction). In this review we summarise the major controversial issues in current reports on VUR and highlight the importance of individualised patient management according to their risk stratification.

Abbreviations: BBD, bladder and bowel dysfunction; CAP, continuous antibiotic prophylaxis; US, ultrasonography; VCUG, voiding cysto-urethrography; RCT, randomised control trial

Keywords: Vesico-ureteric reflux, Urinary tract infection, Renal scars, Dimercaptosuccinic acid (DMSA), Continuous antibiotic prophylaxis, Bladder and bowel dysfunctions, Voiding cysto-urethrography

Introduction

VUR is defined as the back flow of urine from the bladder into the upper urinary tract. VUR is one of the most common paediatric urology entities and has a spectrum of severity that ranges from an asymptomatic self-limiting incidental finding to a condition which is associated with pyelonephritis, renal scarring and even deterioration of kidney function. This variability in the presentation and outcome of the disease raises tremendous controversy about the optimal diagnosis and management strategies.

The challenge with managing VUR is that there is much information that has been published on the topic, comprising 2280 articles in the past 10 years. Most of this information comes from retrospective studies that have not led to a proportionate amount of useful clinical knowledge. Ideally, relative risk for UTI and renal injury should be what drives the clinical management of these patients. The selection of patients, based on risk, who would benefit from early correction of VUR or from cessation of antibiotic prophylaxis remains unclear at best.

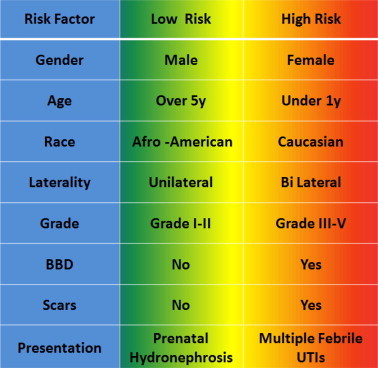

Many large-scale multivariate analyses show that the factors affecting the spontaneous resolution of VUR include demographic factors (age at presentation, gender, ethnicity) and clinical factors (VUR grade, unilateral vs. bilateral, presence of renal scars, initial presentation, the number of UTIs, and the presence of bladder and bowel dysfunction; Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Risk factors and risk groups for VUR.

In this review we summarise the major controversial issues raised by current reports on VUR, and highlight the importance of individualised patient management according to their risk stratification.

The diagnosis of VUR and renal scars

The diagnosis of VUR is made by voiding cysto-urethrography (VCUG), a relatively invasive procedure as it requires bladder catheterisation as well as radiation exposure to the infant pelvis and gonads. The awareness of these two major drawbacks has increased tremendously over the last decade, and many physicians and parents try to avoid this diagnostic study whenever possible.

The classic indications for VCUG include febrile UTI, high-grade or bilateral hydronephrosis and/or ureteric dilatation. These indications have been challenged by numerous publications questioning the yield of this diagnostic test in different patient populations. Hoberman et al. [1] showed, in a prospective trial involving 309 patients, that renal scarring 6 months after the infection is significantly more prevalent in infants with VUR (15% vs. 6%, P = 0.03). Because of this statistically significant finding, and if antimicrobial prophylaxis is effective in reducing re-infections and renal scarring, then VCUG might be a useful test. However, Tseng et al. [2] showed that children with a negative DMSA scan taken after the first UTI episode rarely have VUR and almost never have high-grade VUR. As the yield of continuous antibiotic prophylaxis (CAP) to prevent UTI in patients with low-grade VUR is low, VCUG might not be necessary in all young children having their first febrile UTI when the DMSA scan is negative.

Merguerian et al. [3] suggested that high-resolution ultrasonography (US) of the kidney can accurately detect diffuse renal scars and can be used as a screening tool to determine the need for a DMSA renal scan. In that study a DMSA renal scan resulted in a change in management strategy in only 13% of the patients. The authors recommended the use of a DMSA scan only for very young infants with high-grade VUR, recurrent breakthrough UTI, and/or severe bowel and bladder dysfunction (BBD).

Renal scars are associated with UTIs

Swerkersson et al. [4] reported on the relationship between VUR, UTI, and renal damage. In their study, 303 children aged <2 years were assessed by US, VCUG, and DMSA renal scan within 3 months of their first UTI. They also repeated the DMSA at 1–2 years afterwards. In that study the risk for new febrile UTI increased with the presence and severity of VUR, despite being on CAP, with the risk (95% CI) being: grade I, 1.20 (0.43–3.35); grade II, 2.17 (1.33–3.36); grade III, 2.50 (1.55–4.01), and grades IV–V, 4.61 (3.23–6.57). Interestingly, in boys the renal damage was often congenital, while in girls the scars were acquired and found to be related to severe inflammatory processes.

Management strategies

The physician managing a child with VUR must first exclude any cause of secondary VUR; the latter is defined as VUR caused by any anatomical or functional abnormality of the bladder, bladder outlet or ureter with a normal functioning vesico-ureteric junction. The most common secondary cause comes from bladder pathology that creates excessive storage and emptying pressures, which eventually overwhelm a normal antireflux intramural flap-valve mechanism (neurogenic bladder, bladder exstrophy, PUV, etc.). In this review we focus on the discussion on the patients with primary VUR.

BBDs are associated with UTIs

In 2010 the AUA published guidelines on the management of primary VUR in children [5]. This report used a structured formal meta-analytical technique with rigorous assessment of data-quality and selection. Despite the lack of robust prospective high-quality randomised control trials (RCTs) available, these guidelines succeeded in emphasising the main diagnostic and treatment clinical points, with a focus on the important role that BBD plays in the pathophysiology of VUR. In this meta-analysis, BBD was associated with a greater risk of breakthrough UTI while on CAP (44% vs. 13%, respectively), and a decrease in the rate of spontaneous resolution (31% vs. 61%, respectively). Abnormal bladder function was also associated with reduced success of the endoscopic correction therapy (57% vs. 90%, respectively); however, this association was not found after open ureteric reimplantation. The UTI rate after the procedure was also higher in patients with BBD.

Cap

The principle rationale for antibiotic use in the management of VUR is to prevent UTI and febrile pyelonephritis, which can lead to permanent renal scarring after the infection. Recently, questions about the effectiveness vs. the potential harm of this strategy have been raised, thus resulting in many controversial publications with confusing messages.

Roussey-Kesler et al. [9] randomised 225 children aged 1–3 years with VUR grade I–III into either continuous cotrimoxazole or no CAP. After a follow-up of 18 months there were no significant differences in the incidence of UTI (7% vs. 26% P = 0.2). Interestingly, CAP significantly reduced the incidence of UTI in boys with grade III VUR (P = 0.013). Another example is the study of Garin et al. [7], who completed a multicentre RCT of the role of CAP in patients aged <18 months and with a history of acute pyelonephritis with or without VUR. That study did not support any role for CAP in preventing the recurrence of UTI or in developing renal scars. Furthermore, they found that mild to moderate VUR did not increase the incidence of UTI, pyelonephritis or renal scars in this patient population.

Pennesi et al. [8] showed, in an open-labelled RCT, that CAP is ineffective in reducing the rate of recurrence of pyelonephritis and the induction of renal damage in children aged <30 months who had VUR grade II–IV. This study was criticised as being open-labelled and under-powered, with questionable compliance with CAP treatment. Also contributing to this scrutiny, neither BBD nor the circumcision status of the patient was accounted for in the study. Leslie et al. [9] showed that patients with ongoing VUR in whom CAP had been withdrawn had no greater incidence of UTI than age-matched VUR control patients who remained on prophylaxis.

A recent Swedish VUR trial [10] gave results that are in sharp contrast with other recent studies. The Swedish study was prospectively designed and randomised patients into three arms, i.e. CAP, surveillance only (no antibiotics), and endoscopic VUR correction. In all, 203 patients with grade III–IV VUR (128 girls and eight boys) aged 1–2 years, who mostly presented with a febrile UTI, were followed. Recurrent febrile UTIs were significantly more common in girls (P < 0.001) and were more common on the surveillance protocol than for CAP or endoscopic therapy (57% vs. 19% vs. 23%, respectively, P = 0.01). Interestingly and more importantly, the CAP group had a significantly lower incidence of new renal scars than those randomised to surveillance and endoscopic treatment; new scars were more prevalent after febrile UTIs (11/49, 22%) and the rate of new renal damage was low in boys (in two of 75 boys enrolled). These data support the use of CAP in girls aged <2 years and with grade III–V VUR.

The controversy between the results of the aforementioned study might be explained by the different patient population that was studied. In addition, it again must be highlighted that VUR is a spectrum of disease severity that should not be treated equally. While the studies of Roussey-Kesler et al. [6] and Garin et al. [7] included patients with and without VUR, low-grade VUR and minimal renal scars at entry, the Swedish study showed a significant benefit for CAP in the high-risk group of girls with VUR grade III or above.

The surgical correction of VUR

An absolute indication for correcting VUR includes any failure of other conservative measures, which includes breakthrough UTI while on CAP, noncompliance with CAP, new renal scars during CAP and no resolution after 4 years of follow-up.

The endoscopic correction of VUR is done by injection with a bulking agent beneath the intramural ureter and ureteric orifice. The minimal invasiveness, with the relatively high success rate (>71% in most series) [11] made this procedure very popular over the last decade [12].

As many parents and physicians are opposed to long-term CAP and follow-up with another VCUG, management trends have been changing over the last decade. Lendvay et al. [12] showed, when reviewing a paediatric health information system database, that during 2002–2004 the incidence of open reimplantation for the surgical correction of VUR decreased by 10%, endoscopic correction increased by 300%, and the overall procedure rate increased by 50%.

To maintain credibility, physicians must determine if this shift is truly justifiable and ask if any surgical correction is necessary, i.e. is the increased prevalence in surgical procedures really leading to lower rates of renal injury and failure? Does it reduce the incidence of kidney infection? Again, high-quality prospective data are lacking and the decision is based on retrospective and very selective data.

VUR risk stratification and predictive models

Predictive models are used in various medical disciplines to help individualise treatment strategies. One of the most famous prediction tools is the Framingham Risk Assessment Calculator [13] for estimating the 10-year risk of having a heart attack. More specifically, this is a risk calculator that is based on the prospectively collected data in the Framingham study. After entering basic risk factors such as gender, age, smoking status and serum lipid profile, the probability (as a percentage) of having a heart attack in the next 10 years is calculated.

In paediatric urology these techniques have been applied to VUR, specifically to predict the probability of the spontaneous resolution of VUR. The Children’s Hospital of Boston developed a calculator to predict the spontaneous resolution of VUR by using logistic regression analysis of their retrospectively collected data on 2462 patients [14]. Another example is the computational model from Iowa University, which used the neuronal network method to predict the same point [15]. All those predictive tools are used to predict the resolution of VUR. The next relevant scoring system to be generated is to compute the risk that the individual patient will undergo a complicated clinical course that will require intervention.

Conclusions

The management of paediatric primary VUR is under continuous development. Treatment varies among centres and VUR might be over-treated. Treatment options include observation only, CAP, and surgery. Management goals should be the prevention of breakthrough UTIs and new renal scars. After excluding a secondary cause of VUR, the physician should consider the risk factors affecting the severity of VUR and manage the child accordingly. Risk factors for severe VUR include demographics (age at presentation, gender, ethnicity) and clinical factors (VUR grade, unilateral vs. bilateral, presence of renal scars, initial presentation, the number of UTIs, and presence of BBD).

Conflict of interest

None.

Funding

None.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Arab Association of Urology.

References

- 1.Hoberman A., Charron M., Hickey R.W., Baskin M., Kearney D.H., Wald E.R. Imaging studies after a first febrile urinary tract infection in young children. N Engl J Med. 2003;16:195–202. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tseng M.H., Lin W.J., Lo W.T., Wang S.R., Chu M.L., Wang C.C. Does a normal DMSA obviate the performance of voiding cystourethrography in evaluation of young children after their first urinary tract infection? J Pediatr. 2007;150:96–99. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2006.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Merguerian P.A., Jamal M.A., Agarwal S.K., McLorie G.A., Bägli D.J., Shuckett B. Utility of SPECT DMSA renal scanning in the evaluation of children with primary vesicoureteral reflux. Urology. 1999;53:1024–1028. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(99)00049-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Swerkersson S., Jodal U., Sixt R., Stokland E., Hansson S. Relationship among VUR, UTI and renal damage in children. J Urol. 2007;178:647–651. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peters C.A., Skoog S.J., Arant B.S., Jr., Copp H.L., Elder J.S., Hudson R.G. Summary of the AUA guideline on management of primary vesicoureteral reflux in children. J Urol. 2010;184:1134–1144. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.05.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roussey-Kesler G., Gadjos V., Idres N., Horen B., Ichay L., Leclair M.D. Antibiotic prophylaxis for the prevention of recurrent urinary tract infection in children with low grade vesicoureteral reflux: results from a prospective randomized study. J Urol. 2008;179:674–679. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.09.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garin E.H., Olavarria F., Garcia Nieto V., Valenciano B., Campos A., Young L. Clinical significance of primary vesicoureteral reflux and urinary antibiotic prophylaxis after acute pyelonephritis: a multicenter, randomized, controlled study. Pediatrics. 2006;117:626–632. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pennesi M., Travan L., Peratoner L., Bordugo A., Cattaneo A., Ronfani L. Is antibiotic prophylaxis in children with vesicoureteral reflux effective in preventing pyelonephritis and renal scars? A randomized, controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2008;121:1489–1494. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leslie B., Moore K., Salle J.L., Khoury A.E., Cook A., Braga L.H. Outcome of antibiotic prophylaxis discontinuation in patients with persistent vesicoureteral reflux initially presenting with febrile urinary tract infection: time to event analysis. J Urol. 2010;184:1093–1099. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brandström P., Esbjörner E., Herthelius M., Swerkersson S., Jodal U., Hansson S. The Swedish reflux trial in children: III. Urinary tract infection pattern. J Urol. 2010;184:286–291. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.01.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Routh J.C., Inman B.A., Reinberg Y. Dextranomer/hyaluronic acid for pediatric vesicoureteral reflux: systematic review. Pediatrics. 2010;125:1010. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-2225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lendvay T.S., Sorensen M., Cowan C.A., Joyner B.D., Mitchell M.M., Grady R.W. The evolution of vesicoureteral reflux management in the era of dextranomer/hyaluronic acid copolymer: a pediatric health information system database. J Urol. 2006;176:1867. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.04.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.D’Agostino R.B., Sr., Grundy S., Sullivan L.M., Wilson P. CHD risk prediction group. Validation of the Framingham coronary heart disease prediction scores: results of a multiple ethnic groups investigation. JAMA. 2001;286:180–187. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.2.180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Estrada C.R., Jr., Passerotti C.C., Graham D.A., Peters C.A., Bauer S.B., Diamond D.A. Nomograms for predicting annual resolution rate of primary vesicoureteral reflux: results from 2,462 children. J Urol. 2009;182:1535–1541. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.06.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Knudson M.J., Austin J.C., Wald M., Makhlouf A.A., Niederberger C.S., Cooper C.S. Computational model for predicting the chance of early resolution in children with vesicoureteral reflux. J Urol. 2007;178:1824–1827. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.05.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]