Abstract

Background

Increasingly, the NHS is embracing the use of digital communication technology for communication between clinicians and patients. Policymakers deem digital clinical communication as presenting a solution to the capacity issues currently faced by general practice. There is some concern that these technologies may exacerbate existing inequalities in accessing health care. It is not known what impact they may have on groups who are already marginalised in their ability to access general practice.

Aim

To assess the potential impact of the availability of digital clinician–patient communication on marginalised groups’ access to general practice in the UK.

Design and setting

Realist review in general practice.

Method

A four-step realist review process was used: to define the scope of the review; to search for and scrutinise evidence; to extract and synthesise evidence; and to develop a narrative, including hypotheses.

Results

Digital communication has the potential to overcome the following barriers for marginalised groups: practical access issues, previous negative experiences with healthcare service/staff, and stigmatising reactions from staff and other patients. It may reduce patient-related barriers by offering anonymity and offers advantages to patients who require an interpreter. It does not impact on inability to communicate with healthcare professionals or on a lack of candidacy. It is likely to work best in the context of a pre-existing clinician–patient relationship.

Conclusion

Digital communication technology offers increased opportunities for marginalised groups to access health care. However, it cannot remove all barriers to care for these groups. It is likely that they will remain disadvantaged relative to other population groups after their introduction.

Keywords: access to health care, communication, doctor-patient relations, general practice

INTRODUCTION

The use of digital communications technology is common, for example, 90% of the UK population have a mobile phone.1 Increasingly, the NHS is embracing the use of digital communication technology for communication between clinicians and patients, presently rolling out e-mail (NHSmail2) designed for this purpose.2 Policymakers deem the introduction of such technologies as presenting a solution to the capacity issues currently faced by general practice, and have pushed for their widespread use.3

At present evidence for the impact of these technologies is inconclusive. There is some evidence of clinical effectiveness from the use of digital communication in primary care;4,5 for instance, observational studies have indicated that access to e-mail messaging services leads to improved outcomes,6,7 but systematic reviews of trials have found the evidence base is inconclusive and of poor quality.8–10

GPs are largely not keen on using digital communication for consultation, and several barriers to use have been identified. These include concerns about workload and patient safety, and that introduction of these technologies may exacerbate existing inequalities in accessing health care.11–13 GPs are concerned about restricting access to certain groups because, although most of the population do engage with technology, some do not.14 Older people, those with no educational qualifications, people whose first language is not English, and people with literacy problems or learning disabilities are least likely to engage with digital communication,14–18 and have been shown to be less likely to use digital clinical communication methods for healthcare purposes.19 If there is a move towards digital clinician–patient communication replacing a proportion of current face-to-face consultation, provision in general practice groups who are currently well served with regard to access, such as older people,20,21 may find themselves disadvantaged.

Beyond these groups, there are certain individuals who already face difficulty in accessing general practice and it is unclear what impact digital clinical communication would have on access. Population groups who may have difficulty include those who are physically disabled, those with mental illness, carers, itinerant populations such as refugees, homeless people, and Travellers, and people who do not have occupational flexibility such as casual workers. For some groups the ability to access general practice without having to travel to and go into a building are apparent, for example, the physically disabled and those who do not have occupational flexibility. Therefore this study aimed to investigate the marginalised groups for whom the potential benefits of digital communication are not readily apparent: people with mental illness, refugees, asylum seekers, homeless people, Travellers, and carers.

A realist review was undertaken22–24 to assess the potential impact of the availability of digital clinician–patient communication on marginalised groups’ access to general practice in the UK.

How this fits in

Existing evidence indicates that digital clinical communication may lead to inequalities in access to general practice for certain groups, such as older people. There has been no exploration of the impact on groups that are already marginalised in their ability to access general practice: people with mental illness, refugees, asylum seekers, homeless people, Travellers, and carers. The nature of digital clinical communication means it has the potential to address several barriers faced by these groups including practical access issues, stigma, and access to interpreters. Although there is some benefit from digital communication for marginalised groups, these groups are likely to remain disadvantaged relative to other population groups.

METHOD

A realist review was conducted using a four-step process:24

define the scope of the review;

search for and scrutinise evidence;

extract and synthesise evidence; and

develop a narrative, including hypotheses.

This review method was selected because it allows investigation of what works, for whom, in what circumstances, in what respect, and why; it draws on material from across disciplines and is not restricted by literature type. The review sought to understand how the intervention (digital clinical communication) works in specific contexts (groups marginalised from general practice access) with what outcome (access to clinical care in general practice).

Define the scope of the review

In order to define the scope of the review the literature was searched for opinion pieces and empirical evidence of health professionals’ views on the benefits of digital communication.11,25–27 The authors consulted with 32 GPs and 20 physiotherapists via brief surveys and discussions at professional development events. Over 200 primary care patients of all ages were consulted on their views using the following methods: electronic surveys to GP patient panels, discussions at patient consultation meetings, and surveys undertaken by school-aged children among their peers. Consultations continued until no new opinions were found.

Drawbacks and benefits were identified relating to access, particularly for marginalised groups who find access difficult. It was decided to focus the review on access and the following research questions:

What are the barriers to accessing general practice for marginalised groups?

What impact would the use of digital communication between clinician and patient have on the ability of marginalised groups to access general practice?

The following technologies were included: video technology, e-mail and internet forums, and short text media (SMS). The following marginalised groups were investigated: people with mental illness, refugees, asylum seekers, homeless people, Travellers, and carers.

Search for and scrutinise evidence

Review 1. What are the barriers to accessing general practice for marginalised groups?

A systematic search was conducted for relevant literature (Box 1). Included were English-language papers of empirical research or systematic review conducted in any country. Titles and abstracts were screened initially, and reference lists were screened to identify any further relevant papers. The quality of included studies was assessed to aid in contextualising the findings of the review, rather than to exclude poor-quality studies. Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) qualitative, cohort, and review appraisal tools were used,28 scoring 1 (for ‘yes’), 0.5 (for ‘unclear’), or 0 (for ‘no’) for each item on the checklist.

Box 1. Search terms used for systematic literature searches.

| Review question | Databases searched (1 January 2013 to 7 February 2014) | Search terms (all terms were MeSH terms, except for those marked †) |

|---|---|---|

| Review 1. What are the barriers to accessing general practice for marginalised groups? | Medline, CINAHL, EMBASE, PsycInfo, ASSIA, and Web of Knowledge | “General practice” and “access”† were combined with the following within each database: “mental health” or “mental illness”, or “carer”*, or “refugee”* or “asylum seeker”† or “homeless”† or “gypsy”† or “traveller”† |

| Review 2. What impact would the use of digital communication between clinician and patient have on the ability of marginalised groups to access general practice?a | Medline, CINAHL, EMBASE, PsycInfo, ASSIA, and Web of Knowledge | “email” or “electronic mail” or “text messaging” or “SMS”† or “voice over internet protocol”† or “skype”† and “primary healthcare” or “primary care” and “access to healthcare”† or “health services accessibility” |

The iterative searches for Review 2 are not included here.

Review 2: What impact would the use of digital communication between clinician and patient have on the ability of marginalised groups to access general practice?

Two complementary approaches to finding relevant evidence and theory were used. First, a systematic search for relevant literature was conducted (Box 1), looking for studies set in either primary or secondary care. Titles and abstracts were screened to identify empirical studies specific to the access issues identified in Review 1.

The second approach involved an iterative process of discussion, literature search and review, further discussion, and further literature search and review. Each access barrier for each marginalised group was discussed (from Review 1) and how digital communication could operate to improve access or not was identified. Multiple disciplines were purposively searched (using multidisciplinary search engines, such as Web of Knowledge and Google Scholar) for relevant empirical and review papers, and for well-established theory. These provided evidence to support or refute the authors’ ideas as to whether or not digital communication would improve access, and for alternative mechanisms of action of digital communication for each marginalised group. Search, review, and discussion continued until no new information was found.

Extract and synthesise evidence

From relevant papers found through both searches, the evidence and theory relating to each access barrier faced by a marginalised group was summarised. Then the impact that digital communication between clinician and patient would be likely to have (improved access to clinical care in general practice or not) was identified. Relevant research results were extracted and thematically coded.

Develop a narrative including hypotheses

The barriers to access and the groups known to experience each barrier along with the evidence for the barriers were described. Evidence was then juxtaposed for the impact of digital clinical communication on the barrier. From this, hypotheses were developed of the impact of digital clinical communication on the barrier in question.

RESULTS

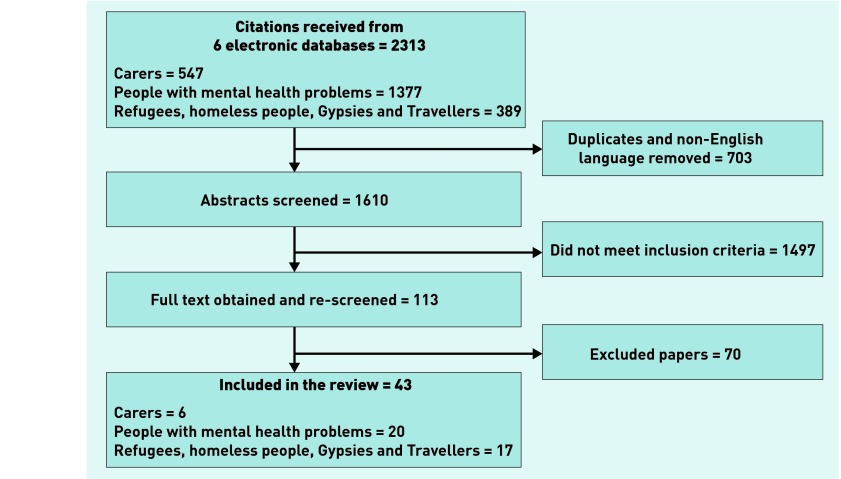

During Review 1, 43 relevant studies were identified (Figure 1) and, during Review 2, 17 relevant studies were identified. An additional 10 studies were identified during the purposive search element of the review (additional details are available from the authors on request). Papers for Review 1 were predominantly qualitative and cross-sectional studies, many with methodological weaknesses. Review 2 included theory, experimental and qualitative research, and systematic reviews. Evidence for both reviews was from high-income countries.

Figure 1.

Literature search flow chart.

Synthesis of findings

Six barriers to access and evidence for how digital communication may impact on these barriers were identified: practical access issues; lack of candidacy; lack of ability to communicate with healthcare professionals; patient-related barriers; negative experiences with healthcare service and staff; and stigmatising and negative reactions to patients.

Practical access issues

These were experienced by carers and people with mental health problems. The barriers identified were lack of respite care for care recipients,29 inflexible appointments,30 unknown waiting times,30 service availability,1 transport difficulties,31–33 difficulties negotiating appointments and receptionists,34 and the stress and discomfort of waiting in the waiting room.34

Digital clinical communication improved access to general practice as practical barriers were overcome. E-mail offered efficiency, speed, and flexibility, for example, patients and carers could use e-mail to communicate with their clinician while at work.13,35 Asynchronous technology can be used to communicate whenever is convenient for the patient or carer, reducing the need to negotiate receptionists or appointment systems, travel to the surgery, and use waiting rooms.35–38

Lack of candidacy

This was experienced by carers. The barrier identified was that health professionals focus on the needs of the care recipient, with the needs of the carer considered only in terms of what is needed to provide care.30,39–42 Increasing the range of channels through which carers can access general practice will not impact on perceived candidacy because identifying oneself as a candidate for health care is necessary before starting the help-seeking process.43

Lack of ability to communicate with healthcare professionals

This was experienced by refugees and asylum seekers, and people with mental health problems. The barriers identified were language barriers affecting the appointment booking and consultation,44–56 problematic access to professional interpreters,44,48–50,52,57–59 confidentiality fears with both professional and informal interpreters,44,49,58 and lack of discourse to describe mental health concerns.60,61

Digital clinical communication will not change the ability of these disadvantaged groups in communicating with health professionals, with the exception being language translation. There is an increased feeling of privacy when an interpreter is not physically present, which increases willingness to discuss sensitive issues.62 However, people whose first language is not English are not heavy users of digital communication in English-speaking countries,16,63 so this advantage may not be realised.

Patient-related barriers

These were experienced by refugees and asylum seekers, homeless people, and Gypsies and Travellers. The barriers identified were mobility of populations and lack of continuity,51,58,64 unwillingness to divulge address (for personal safety, such as women living in domestic violence shelters, or fear of legal repercussions, such as failed asylum seekers),65 and patients’ lack of knowledge about health service structure and how to access services.47,50

Digital clinical communication improves continuity of care for mobile populations and those unwilling to divulge their address,13,66,67 and the relative anonymity provided could encourage populations who wish to remain hidden to seek help.66,68 However, this type of communication alone will not improve knowledge about health service structure and how to access services. The authors were unable to find any evidence on these factors.

Negative experiences with healthcare service and staff

This was experienced by people with mental health problems, refugees and asylum seekers, homeless people, and Gypsies and Travellers. The barriers identified were staff not being seen as sensitive,44,55,69–71 difficult relationships with GPs,51,71–73 negative perceptions of GPs’ knowledge, skills, and empathy for mental health problems,34,60,61,74,75 distrust in GPs and their abilities,51 communication difficulties due to mental health problems,60 and service-wide lack of awareness of patients’ rights and acceptance of official documentation.52,58

Digital clinical communication will improve continuity of care from a trusted clinician, but where there is no existing patient–clinician relationship it will reduce the quality of communication between patient and clinician. Social presence theory76 states that interpersonal processes are negatively affected by interaction that takes place via media that reduces the feeling of ‘being there’ with each other. In order to build the therapeutic relationship, clinicians and patients need to have face-to-face contact for the richness of stimuli available, including auditory, visual, tactile, and olfactory.37 Patients try to see trusted GPs for mental health issues rather than the most available GP,77,78 prioritising relationship continuity over convenience. Text-based communication in well-established relationships is likely to be more successful than that between strangers because of the room for misinterpretation.37,79

Additionally, digital clinical communication would reduce the need for patients to engage with receptionists and other health centre staff,35–37 ameliorating apprehension about negative experiences with these staff.

No evidence was found that digital communication will in itself improve patients’ trust in general practice clinicians, or increase health services’ awareness of patients’ rights.

Stigmatising and negative reactions to patients

This was experienced by people with mental health problems, refugees and asylum seekers, homeless people, and Gypsies and Travellers. The barriers identified were stigma and hostile attitudes (from healthcare staff and other patients),50,56,60,73–75,81–84 embarrassment,74,85,86 fear,74 social (dis)approval,31,73 and perceived discrimination.32,73,86

Digital clinical communication may reduce patients’ inhibition and sense of intimidation, and promote patient disclosure and asking of questions. Patients consulting for physical problems feel less intimidated via video link and able to ask more questions.90 Kang and colleagues91 found that teenage girls willingly emailed a health professional in a magazine column to discuss problems/queries that they would not necessarily talk about face to face. Online disinhibition theory92 suggests that people express themselves more openly, disclose more, and say things in cyberspace that they would not face to face. The removal of the patient ‘being seen’ seeking help potentially removes the embarrassment, social disapproval, and stigma that some patients may experience at healthcare centres.68,93 Although one review suggested that face-to-face consultations were essential for communication about emotional states,87 other evidence suggests that patients do communicate their emotional states with GPs via e-mail,88 and are able to discuss embarrassing or sensitive questions.89

Table 1 summarises the barriers to general practice access, groups known to experience each barrier, evidence for the impact of digital clinical communication on each barrier, and emerging hypotheses of the impact of digital clinical communication on the barrier in question.

Table 1.

Barriers to general practice access, groups known to experience each barrier, evidence for the impact of digital clinical communication on each barrier, and emerging hypotheses of the impact of digital clinical communication on the barrier in question

| Barriers | Groups | Evidence for barriers | Evidence for impact of digital clinical communication on barrier | Hypotheses developed from evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Practical access issues | Carers; people with mental health problems | E-mail used to contact GP because of its efficiency, speed, and flexibility (for example, patients could use e-mail to communicate with a GP while at work)13,35 Carers’ use of digital communication technologies occurs outside of office hours; provide convenient, flexible, and quick ways of accessing information and help80 Asynchronous technology can be used to communicate whenever is convenient for the patient, reducing the need to negotiate receptionists or appointment systems, travel to the surgery, and use waiting rooms35–37 |

Improved access to general practice via digital communication as practical barriers overcome | |

| Lack of candicacy | Carers | Identifying oneself as a candidate for health care is necessary before starting the help-seeking process43 | Increasing the range of channels through which carers can access general practice will not impact on perceived candidacy | |

| Lack of ability to communicate with health professionals | Refugees and asylum seekers; people with mental health problems | Feeling of privacy increased when interpreter is not physically present, increasing patient willingness to discuss sensitive issues; loss of visual information can reduce interpretation quality62 People whose first language is not English are not heavy users of digital communication in English-speaking countries16,63 |

Communication technology will not change ability of these disadvantaged groups in communicating with health professionals, with the exception being language translation | |

| Patient-related barriers | Refugees and asylum seekers; homeless people; Gypsies and Travellers | Communication technology facilitates continuity of care13,66,67 Anonymity provided by digital communication could encourage populations who wish to remain hidden to seek help66,68 No evidence found on the impact on patient knowledge about health services related to the availability of digital communication for clinician–patient communication |

Communication technology improves continuity of care for mobile populations and those unwilling to divulge their address Communication technology alone will not improve knowledge about health service structure and how to access services |

|

| Negative experiences with healthcare service and staff | People with mental health problems; refugees and asylum seekers; homeless people; Gypsies and Travellers | Patients try to see trusted GPs for mental health issues rather than the most available GP,77,78 prioritising relationship continuity over convenience Text-based communication leaves much room for interpretation, therefore communication between patients and clinicians with well-established relationships is likely to be more successful than that between strangers37,79 To build the therapeutic relationship, clinicians and patients need to have face-to-face contact for the richness of stimuli available, for example, auditory, visual, tactile and olfactory37 Social presence theory76 states that interpersonal processes are negatively affected by interaction that takes place via media that reduces the feeling of ‘being there’ with each other Digital clinical communication would reduce the need for patients to engage with receptionists and other health centre staff,35–37 ameliorating apprehension about negative experiences with these staff No evidence found that digital communication will in itself improve patients’ trust in the GP, or increase health services’ awareness of patients’ rights |

Communication technology will improve continuity of care from a trusted clinician Where there is no existing patient–clinician relationship the use of communication technology will reduce the quality of communication between patient and clinician |

|

| Stigmatising and negative reactions to patients | People with mental health problems; refugees and asylum seekers; homeless people; Gypsies and Travellers | One review suggested that face-to-face consultations were essential for communication about emotional states.87 Other evidence suggests that patients do communicate their emotional states with GPs via email,88 and are able to discuss embarrassing or sensitive questions89 Patients consulting for physical problems can feel less intimidated via video link and able to ask more questions90 One review found that teenage girls willingly emailed a health professional in a magazine column to discuss problems/queries that they would not necessarily talk about face to face91 Online disinhibition theory suggests people express themselves more openly, disclose more, and say things in cyberspace that they would not face to face88 The removal of the patient ‘being seen’ seeking help potentially removes the embarrassment, social disapproval, and stigma that some patients may experience at healthcare centres68,93 |

Digital clinical communication will reduce patients’ inhibition and sense of intimidation and promote patient disclosure and asking of questions |

DISCUSSION

Summary

This study assessed the potential impact of the availability of digital clinician–patient communication on marginalised groups’ access to general practice in the UK. It has demonstrated that digital communication between clinician and patient has the potential to overcome the following barriers for these groups: practical access issues, negative experiences with healthcare service and staff, and stigmatising and negative reactions from staff and other patients. It may reduce patient-related barriers by providing a level of anonymity and offers advantages to patients who require an interpreter to consult. It otherwise does not impact on a lack of ability to communicate with healthcare professionals, nor on a lack of candidacy and knowledge about health services. It is likely to work best in the context of a pre-existing clinician–patient relationship.

Strengths and limitations

By using a realist approach for the evidence review, evidence was drawn from many disciplines to answer a research question for general practice, at a time when little good-quality evidence exists, and before the UK NHS has systems in place to support digital communication between clinician and patient. This is important for establishing realistic expectations of the benefit of digital communication between clinician and patient.

The review drew on evidence from multiple disciplines and types of healthcare provision. So, although focused on general practice, the review results are likely to be relevant for other healthcare settings where the clinician–patient consultation is a key element.

The review does not include all marginalised groups. It did not include people with physical disabilities because the benefits of not needing to physically access a building are apparent. It did not include people for whom the use of digital communication is dependent on adaptation of the user interface, such as those with a sensory or learning disability. The marginalised groups included are likely to share characteristics with marginalised groups that were not included, such as sex workers.94 However, it was not possible to identify research evidence on the relative advantages and disadvantages of digital communication with visual cues such as videoconference, compared with text-based cues such as e-mail. As the review considered UK general practice, where health care is free at the point of access, it did not consider whether the use of clinician–patient digital communication would improve access through reducing the cost for the patient.

Comparison with existing literature

Clinician–patient interactions are changing, becoming more patient centred,95,96 and increasingly health professionals are promoting flexible approaches to consultations.97 The review concurs with previous research findings that digital communication between clinician and patient increases patient flexibility, choice, and convenience.37,98 However, use of the technology could create access problems if availability of traditional consultations were considerably reduced because the quality of the consultation is better if there is a pre-existing clinician–patient relationship.

It seems that provision of digital clinician–patient communication could improve access for some marginalised groups. However, such provision will be inconsequential for many people unless widespread access to the internet improves, websites and text-based communication conform to accessibility and plain-English standards, and assistive technologies are used.15 Although this review suggests that the use of communication technology could improve access for homeless people, these people are often physically excluded from public internet access points.99 Furthermore, people with more chaotic lives use such technology sporadically and not dependably.99

Implications for research and practice

The World Health Organization has established the goal for all people to have access to timely, acceptable, and affordable health care of appropriate quality.100 There is widespread expectation that the use of digital communication between clinician and patient will improve access to health care for marginalised groups. This review suggests there are likely to be some benefits. However, many barriers will remain and not all marginalised groups will be able to gain benefit due to their limited access to digital communication technology. As the benefits of increased access for marginalised groups also apply to non-marginalised groups, the provision of digital clinician–patient communication could potentially be monopolised by those who are already well able to access services and have good access to digital technology. This is something that is yet to be investigated. The cost to both health service providers and patients will also have implications for patterns of access. There is therefore a need to evaluate the impact of the introduction of digital clinician–patient communication on population patterns of access to health care. Further research is needed to understand how digital communication impacts on the acceptability and quality of health care. This includes the impact on clinician–patient communication and the relative advantages and disadvantages of communication with and without visual cues.

In conclusion, digital communication technology offers increased opportunities for marginalised groups to access health care, and general practice can make the most of these. These technologies cannot, however, remove all barriers to care for marginalised groups and it is likely that these groups will remain disadvantaged relative to other population groups, even after their introduction.

Funding

Arden Cluster Research Capability Fund. Helen Atherton is funded by an NIHR SPCR fellowship.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Provenance

Freely submitted; externally peer reviewed.

Competing interests

The authors have declared no competing interests.

Discuss this article

Contribute and read comments about this article: bjgp.org/letters

REFERENCES

- 1.OFCOM Media: facts & figures. http://media.ofcom.org.uk/facts/ (accessed 27 Oct 2015).

- 2.Health and Social Care Information Centre Health and Social Care Information Centre. NHSmail2. http://systems.hscic.gov.uk/nhsmail/future (accessed 27 Oct 2015).

- 3.Department of Health The power of information: Putting all of us in control of the health and care information we need. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/giving-people-control-of-the-health-and-care-information-they-need (accessed 27 Oct 2015).

- 4.McLean S, Chandler D, Nurmatov U, et al. Telehealthcare for asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(10):CD007717. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007717.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McLean S, Nurmatov U, Liu JL, et al. Telehealthcare for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(7):CD007718. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007718.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhou YY, Kanter MH, Wang JJ, Garrido T. Improved quality at Kaiser Permanente through e-mail between physicians and patients. Health Aff. 2010;29(7):1370–1375. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Palen TE, Ross C, Powers JD, Xu S. Association of online patient access to clinicians and medical records with use of clinical services. JAMA. 2012;308(19):2012–2019. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.14126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Atherton H, Sawmynaden P, Sheikh A, et al. Email for clinical communication between patients/caregivers and healthcare professionals. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(11):CD007978. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007978.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Currell R, Urquhart C, Wainwright P, Lewis R. Telemedicine versus face to face patient care: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000;(2):CD002098. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Jongh T, Gurol-Urganci I, Vodopivec-Jamsek V, et al. Mobile phone messaging for facilitating self-management of long-term illnesses. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(12):CD007459. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007459.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hanna L, May C, Fairhurst K. The place of information and communication technology-mediated consultations in primary care: GPs’ perspectives. Fam Pract. 2012;29(3):361–366. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmr087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Neville RG, Marsden W, McCowan C, et al. A survey of GP attitudes to and experiences of email consultations. Inform Prim Care. 2004;12(4):201–206. doi: 10.14236/jhi.v12i4.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Atherton H, Pappas Y, Heneghan C, Murray E. Experiences of using email for general practice consultations: a qualitative study. Br J Gen Pract. 2013 doi: 10.3399/bjgp13X674440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dutton WH, Blank G. Cultures of the internet: the internet in Britain. Oxford: Oxford Internet Institute; 2013. http://oxis.oii.ox.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/43/2014/11/OxIS-2013.pdf (accessed 2 Oct 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boeltzig-Brown H, Pilling D. Bridging the digital divide for hard-to-reach groups. Washington, DC: The IBM Centre for the Business of Government; 2007. http://businessofgovernment.org/report/bridging-digital-divide-hard-reach-groups (accessed 2 Oct 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zickuhr K, Smith A. Digital differences. 2012 http://www.pewinternet.org/2012/04/13/digital-differences/ (accessed 2 Oct 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hill JH, Burge S, Haring A, et al. Communication technology access, use, and preferences among primary care patients: from the Residency Research Network of Texas (RRNeT) J Am Board Fam Med. 2012;25(5):625–634. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2012.05.120043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nijland N, van Gemert-Pijnen JE, Boer H, et al. Increasing the use of e-consultation in primary care: results of an online survey among non-users of e-consultation. Int J Med Inform. 2009;78(10):688–703. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2009.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Newhouse N, Lupiáñez-Villanueva F, Codagnone C, Atherton H. Patient use of email for health care communication purposes across 14 European countries: an analysis of users according to demographic and health-related factors. J Med Internet Res. 2015;17(3):e58. doi: 10.2196/jmir.3700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hippisley-Cox J, Vinogradova Y. Trends in consultation rates in general practice 1995/1996 to 2008/2009: analysis of the QResearch ® database. Leeds: Health and Social Care Information Centre; 2009. http://www.hscic.gov.uk/catalogue/PUB01077/tren-cons-rate-gene-prac-95-09-95-09-rep.pdf (accessed 2 Oct 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 21.van der Meer JB, Mackenbach JP. Low education, high GP consultation rates: the effect of psychosocial factors. J Psychosom Res. 1998;44(5):587–597. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(97)00217-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pawson R, Greenhalgh T, Harvey G, Walshe K. Realist review: a new method of systematic review designed for complex policy interventions. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2005;10(Suppl 1):21–34. doi: 10.1258/1355819054308530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wong G, Greenhalgh T, Westhorp G, et al. RAMESES publication standards: realist syntheses. BMC Med. 2013;11:21. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-11-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rycroft-Malone J, McCormack B, Hutchinson AM, et al. Realist synthesis: illustrating the method for implementation research. Implement Sci. 2012;7:33. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-7-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jadad AR, Delamothe T. What next for electronic communication and health care? BMJ. 2004;328(7449):1143–1144. doi: 10.1136/bmj.328.7449.1143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wong G. Increasing email consultations may marginalise more people. BMJ. 2001;323:1189. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7322.1189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Neville RG, Marsden W, McCowan C, et al. A survey of GP attitudes to and experiences of email consultations. Inform Prim Care. 2004;12(4):201–206. doi: 10.14236/jhi.v12i4.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.CASP UK Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. 2013. http://www.casp-uk.net/#!casp-tools-checklists/c18f8 (accessed 27 Oct 2015).

- 29.Simon C, Kumar S, Kendrick T. Who cares for the carers? The district nurse perspective. Fam Pract. 2002;19(1):29–35. doi: 10.1093/fampra/19.1.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Arksey H, Hirst M. Unpaid carers’ access to and use of primary care services. Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2005;6(2):101–116. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dupree LW, Herrera JR, Tyson DM, et al. Age group differences in mental health care preferences and barriers among Latinos. Best Pract Ment Health. 2010;6(1):47–59. [Google Scholar]

- 32.McCann TV, Clark E. A grounded theory study of the role that nurses play in increasing clients’ willingness to access community mental health services. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2003;12(4):279–287. doi: 10.1046/j.1447-0349.2003.t01-6-.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zeber JE, Copeland LA, McCarthy JF, et al. Perceived access to general medical and psychiatric care among veterans with bipolar disorder. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(4):720–727. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.131318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lester H, Tritter JQ, Sorohan H. Patients’ and health professionals’ views on primary care for people with serious mental illness: focus group study. BMJ. 2005;330(7500):1122. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38440.418426.8F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bergmo TS, Kummervold PE, Gammon D, Dahl LB. Electronic patient-provider communication: will it offset office visits and telephone consultations in primary care? Int J Med Inform. 2005;74(9):705–710. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2005.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ye J, Rust G, Fry-Johnson Y, Strothers H. E-mail in patient-provider communication: a systematic review. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;80(2):266–273. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.09.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moyer CA, Katz SJ. Online patient-provider communication: how will it fit? Electronic Journal of Communication. 2007;17:3–4. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Read M, Byrne P, Walsh A. Dial a clinic: a new approach to reducing the number of defaulters. Br J Healthcare Management. 1997;3:307–310. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Greenwood N, Mackenzie A, Habibi R, et al. General practitioners and carers: a questionnaire survey of attitudes, awareness of issues, barriers and enablers to provision of services. BMC Fam Pract. 2010;11:100. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-11-100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Greenwood N, Mackenzie A, Harris R, et al. Perceptions of the role of general practice and practical support measures for carers of stroke survivors: a qualitative study. BMC Fam Pract. 2011;12:57. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-12-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Katbamna S, Bhakta P, Ahmad W, et al. Supporting South Asian carers and those they care for: the role of the primary health care team. Br J Gen Pract. 2002;52(477):300–305. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Merrell J, Kinsella F, Murphy F, et al. Accessibility and equity of health and social care services: exploring the views and experiences of Bangladeshi carers in South Wales, UK. Health Soc Care Community. 2006;14(3):197–205. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2006.00610.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dixon-Woods M, Cavers D, Agarwal S, et al. Conducting a critical interpretive synthesis of the literature on access to healthcare by vulnerable groups. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2006;6:35. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-6-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bhatia R, Wallace P. Experiences of refugees and asylum seekers in general practice: a qualitative study. BMC Fam Pract. 2007;8:48. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-8-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Duncan G, Harding C, Gilmour A, Seal A. GP and registrar involvement in refugee health: a needs assessment. Aust Fam Physician. 2013;42(6):405–408. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Guerin PB, Guerin B, Abdi A. Experiences with the medical and health systems for Somali refugees living in Hamilton. NZ J Psychol. 2003;32(1):27–32. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Johnson DR, Ziersch AM, Burgess T. I don’t think general practice should be the front line: experiences of general practitioners working with refugees in South Australia. Aust New Zealand Health Policy. 2008;5:20. doi: 10.1186/1743-8462-5-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.MacFarlane A, Dzebisova Z, Karapish D, et al. Arranging and negotiating the use of informal interpreters in general practice consultations: experiences of refugees and asylum seekers in the west of Ireland. Soc Sci Med. 2009;69(2):210–214. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.MacFarlane A, Glynn LG, Mosinkie PI, Murphy AW. Responses to language barriers in consultations with refugees and asylum seekers: a telephone survey of Irish general practitioners. BMC Fam Pract. 2008;9:68. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-9-68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.O’Donnell CA, Higgins M, Chauhan R, Mullen K. ‘They think we’re OK and we know we’re not’. A qualitative study of asylum seekers’ access, knowledge and views to health care in the UK. BMC Health Serv Res. 2007;7:75. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-7-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.O’Donnell CA, Higgins M, Chauhan R, Mullen K. Asylum seekers’ expectations of and trust in general practice: a qualitative study. Br J Gen Pract. 2008 doi: 10.3399/bjgp08X376104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sinha S, Uppal S, Pryce A. ‘I had to cry’: exploring sexual health with young separated asylum seekers in East London. Diversity in Health and Social Care. 2008;5(2):101–111. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Green G, Bradby H, Chan A, et al. Is the English National Health Service meeting the needs of mentally distressed Chinese women? J Health Serv Res Policy. 2002;7(4):216–221. doi: 10.1258/135581902320432741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jensen NK, Norredam M, Priebe S, Krasnik A. How do general practitioners experience providing care to refugees with mental health problems? A qualitative study from Denmark. BMC Fam Pract. 2013;14:17. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-14-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Li PL, Logan S, Yee L, Ng S. Barriers to meeting the mental health needs of the Chinese community. J Public Health Med. 1999;21(1):74–80. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/21.1.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tabassum R, Macaskill A, Ahmad I. Attitudes towards mental health in an urban Pakistani community in the United Kingdom. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2000;46(3):170–181. doi: 10.1177/002076400004600303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Buizza C, Schulze B, Bertocchi E, et al. The stigma of schizophrenia from patients’ and relatives’ view: a pilot study in an Italian rehabilitation residential care unit. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health. 2007;3:23. doi: 10.1186/1745-0179-3-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nyiri P, Eling J. A specialist clinic for destitute asylum seekers and refugees in London. Br J Gen Pract. 2012;62(604):599–600. doi: 10.3399/bjgp12X658386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rosenberg E, Richard C, Lussier MT, Shuldiner T. The content of talk about health conditions and medications during appointments involving interpreters. Fam Pract. 2011;28(3):317–322. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmq094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kravitz RL, Paterniti DA, Epstein RM, et al. Relational barriers to depression help-seeking in primary care. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;82(2):207–213. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2010.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Van Den Tillaart S, Kurtz D, Cash P. Powerlessness, marginalized identity, and silencing of health concerns: voiced realities of women living with a mental health diagnosis. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2009;18(3):153–163. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0349.2009.00599.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Masland MC, Lou C, Snowden L. Use of communication technologies to cost-effectively increase the availability of interpretation services in healthcare settings. Telemed J E Health. 2010;16(6):739–745. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2009.0186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kabbar EF, Crump BJ. The factors that influence adoption of ICTs by recent refugee immigrants to New Zealand. Informing Sci J. 2006;9:111–121. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Varnam R, Varnam M. Integrating the single homeless into mainstream general practice. Health Trends. 1993;25(3):112–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Webb E, Shankleman J, Evans MR, Brooks R. The health of children in refuges for women victims of domestic violence: cross sectional descriptive survey. BMJ. 2001;323(7306):210–213. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7306.210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Berg JW. Ethics and e-medicine. St Louis Univ Law J. 2002;46(1):61–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Miller EA. Telemedicine and doctor-patient communication: a theoretical framework for evaluation. J Telemed Telecare. 2002;8(6):311–318. doi: 10.1258/135763302320939185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Miller EA. The technical and interpersonal aspects of telemedicine: effects on doctor-patient communication. J Telemed Telecare. 2003;9(1):1–7. doi: 10.1258/135763303321159611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Feder G. Traveller gypsies and primary care. J R Coll Gen Pract. 1989;39(327):425–429. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Feldmann CT, Bensing JM, de Ruijter A, Boeije HR. Afghan refugees and their general practitioners in the Netherlands: to trust or not to trust? Sociol Health Illn. 2007;29(4):515–535. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2007.01005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bailey D. What is the way forward for a user-led approach to the delivery of mental health services in primary care? J Ment Health. 1997;6(1):101–106. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Khandor E, Mason K, Chambers C, et al. Access to primary health care among homeless adults in Toronto, Canada: results from the Street Health survey. Open Med. 2011;5(2):e94–e103. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Pfeil M, Howe A. Ensuring primary care reaches the ‘hard to reach’. Qual Prim Care. 2004;12(3):185–190. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Davidson J. Caring and daring to complain: an examination of UK National Phobics Society members’ perception of primary care. Soc Sci Med. 2007;65(3):560–571. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Howerton A, Byng R, Campbell J, et al. Understanding help seeking behaviour among male offenders: qualitative interview study. BMJ. 2007;334(7588):303. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39059.594444.AE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Short J, Williams E, Christie B. The social psychology of telecommunications. London: John-Wiley & Sons; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Guthrie B, Wyke S. Personal continuity and access in UK general practice: a qualitative study of general practitioners’ and patients’ perceptions of when and how they matter. BMC Fam Pract. 2006;7:11. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-7-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kearley KE, Freeman GK, Heath A. An exploration of the value of the personal doctor–patient relationship in general practice. Br J Gen Pract. 2001;51(470):712–718. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Martin S, Sutcliffe P, Griffiths F, et al. Effectiveness and impact of networked communication interventions in young people with mental health conditions: a systematic review. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;85(2):e108–e119. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2010.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Read J, Blackburn C. Carers’ perspectives on the internet: implications for social and health care service provision. Br J Soc Work. 2005;35(7):1175–1192. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kim MM, Swanson JW, Swartz MS, et al. Healthcare barriers among severely mentally ill homeless adults: evidence from the five-site health and risk study. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2007;34(4):363–375. doi: 10.1007/s10488-007-0115-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Farrand P, Duncan F, Byng R. Impact of graduate mental health workers upon primary care mental health: a qualitative study. Health Soc Care Community. 2007;15(5):486–493. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2007.00707.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Robinson WD, Springer PR, Bischoff R, et al. Rural experiences with mental illness: through the eyes of patients and their families. Fam Syst Health. 2012;30(4):308–321. doi: 10.1037/a0030171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Thornicroft G, Rose D, Kassam A. Discrimination in health care against people with mental illness. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2007;19(2):113–122. doi: 10.1080/09540260701278937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Tedstone Doherty D, Kartalova-O’Doherty Y. Gender and self-reported mental health problems: predictors of help seeking from a general practitioner. Br J Health Psychol. 2010;15(1):213–228. doi: 10.1348/135910709X457423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ward EC, Clark le O, Heidrich S. African American Women’s beliefs, coping behaviors, and barriers to seeking mental health services. Qual Health Res. 2009;19(11):1589–1601. doi: 10.1177/1049732309350686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ong LM, de Haes JC, Hoos AM, Lammes FB. Doctor-patient communication: a review of the literature. Soc Sci Med. 1995;40(7):903–918. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)00155-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Roter DL, Larson S, Sands DZ, et al. Can e-mail messages between patients and physicians be patient-centered? Health Commun. 2008;23(1):80–86. doi: 10.1080/10410230701807295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Wallwiener M, Wallwiener CW, Kansy JK, et al. Impact of electronic messaging on the patient-physician interaction. J Telemed Telecare. 2009;15(5):243–250. doi: 10.1258/jtt.2009.090111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Tachakra S, Rajani R. Social presence in telemedicine. J Telemed Telecare. 2002;8(4):226–230. doi: 10.1258/135763302320272202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kang M, Cannon B, Remond L, Quine S. ‘Is it normal to feel these questions ...?’: a content analysis of the health concerns of adolescent girls writing to a magazine. Fam Pract. 2009;26(3):196–203. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmp019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Suler J. The online disinhibition effect. Cyberpsychol Behav. 2004;7(3):321–326. doi: 10.1089/1094931041291295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Taylor B. HIV, stigma and health: integration of theoretical concepts and the lived experiences of individuals. J Adv Nurs. 2001;35(5):792–798. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2001.01912.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Jeal N, Salisbury C. A health needs assessment of street-based prostitutes: cross-sectional survey. J Public Health. 2004;26(2):147–151. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdh124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Stewart MB, Brown JB, Weston WW, et al. Patient-centered medicine: transforming the clinical method. 2nd edn. Abingdon: Radcliffe Medical Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Kurtz SM, Silverman JD. The Calgary-Cambridge Referenced Observation Guides: an aid to defining the curriculum and organizing the teaching in communication training programmes. Med Educ. 1996;30(2):83–89. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.1996.tb00724.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Griffiths F, Cave J, Boardman F, et al. Social networks: the future for health care delivery. Soc Sci Med. 2012;75(12):2233–2241. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Whitten PS, Mair FS, Haycox A, et al. Systematic review of cost effectiveness studies of telemedicine interventions. BMJ. 2002;324(7351):1434–1437. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7351.1434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Bure C. Digital inclusion without social inclusion: the consumption of information and communication technologies (ICTs) within homeless subculture in Scotland. Journal of Community Informatics. 2005;1(2):116–133. [Google Scholar]

- 100.World Health Organization . The right to health Fact sheet number 323. Geneva: WHO; 2013. [Google Scholar]