Abstract

Flightin is a myosin binding phosphoprotein that originated in the ancestor to Pancrustacea ~500 MYA. In Drosophila melanogaster, flightin is essential for length determination and flexural rigidity of thick filaments. Here, we show that among 12 Drosophila species, the N-terminal region is characterized by low sequence conservation, low pI, a cluster of phosphorylation sites, and a high propensity to intrinsic disorder (ID) that is augmented by phosphorylation. Using mass spectrometry, we identified eight phosphorylation sites within a 29 amino acid segment in the N-terminal region of D. melanogaster flightin. We show that phosphorylation of D. melanogaster flightin is modulated during flight and, through a comparative analysis to orthologs from other Drosophila species, we found phosphorylation sites that remain invariant, sites that retain the charge character, and sites that are clade-specific. While the number of predicted phosphorylation sites differs across species, we uncovered a conserved pattern that relates the number of phosphorylation sites to pI and ID. Extending the analysis to orthologs of other insects, we found additional conserved features in flightin despite the near absence of sequence identity. Collectively, our results demonstrate that structural constraints demarcate the evolution of the highly variable N-terminal region.

INTRODUCTION

Insects have an ~390 million year history and account for more than half of all known species of living organisms [1, 2]. The Insecta is the most diverse class on Earth and widely considered the most successful terrestrial metazoans. Success of insects and particularly winged insects, is measured not only in terms of sheer number of species but also in terms of distribution, colonization of diverse habitats, and population sizes. Flight, which originated in insects, was a pivotal event in the history of life as the transition to air increased opportunities for colonization of new habitats, niche exploitation, and adaptive radiation [3]. More specifically, the advantages conferred to flying insects include predator avoidance, location of new food sources, and travel to and exploration of new habitats. Approximately 70% of extant insect species can fly, an indication that flight remains a critical attribute for insect survival [1].

Insect flight is made possible by muscles that power the wings categorized as asynchronous and synchronous. The asynchronous indirect flight muscle (IFM), widely considered among the most powerful muscle types, is derived from the ancestral, synchronous muscle type. Evolutionary reconstruction of IFM and asynchrony suggest as many as 10 independent origins for this complex character [4–6]. IFM is found only in Paraneoptera and Holometabola and is a fixture of species comprising three of the four most speciose orders of insects (Diptera, Hymenoptera, and Coleoptera). This evidence supports the classification of muscle asynchrony as a key innovation that has allowed rapid radiation and diversification of insects [7]. Elucidation of the molecular adaptations that have contributed to the rise of IFM remains an important problem in evolutionary biology.

Flightin is a 20,000 Da thick filament protein that in Drosophila melanogaster is expressed exclusively in the IFM [8]. Flies deficient for flightin (fln0) are flightless and display a characteristic time-dependent fiber hypercontraction, a manifestation of a structurally compromised myofilament lattice [9]. The timing of hypercontraction in fln0 flies coincides with a period of rapid increase in phosphorylation of flightin (and other contractile proteins) in wild-type flies that precede the acquisition of flight competency [10]. The hypercontraction phenotype is suppressed by mutations in the myosin motor domain [11], an indication that the myofilament lattice is stable insofar as it is not subject to stress or strain.

Characterization of flightin mutants in Drosophila melanogaster has revealed how flightin function manifests across levels of biological hierarchy by contributing to length determination and flexural rigidity of thick filaments, sarcomere organization, myofibril integrity, fiber contractile mechanics, and flight behavior [9, 12–18]. Phylogenetic and protein sequence analyses revealed that flightin is endemic to Pancrustacea (Hexapoda + Crustacea) and led to the identification of WYR, a novel ~52 amino acid protein domain characterized by strictly conserved tryptophan (W) and arginine (R) sites and a high content of tyrosines (Y) [19]. In contrast to WYR, the sequences flanking this core domain are poorly conserved with the N-terminal region showing the greatest sequence variation. Here, we present evidence that the N-terminal region of flightin is evolving at a faster rate than the rest of the protein. Amid the variation in amino acid sequence, we find conserved features indicative of functional constraints that dictate the evolution of flightin.

MATERIALS & METHODS

Flight assays

Drosophila melanogaster (Oregon R) were maintained at 25°C in a 12:12 light:dark cycle and aged to 3–5 days post-eclosion for testing. Female flies were rendered immobile using CO2 and a 3–5 mm long, 2.5 lb fishing line was attached to the fly head using Krazy Glue. Tethered flies were set in a food vial to recover for approximately 24 hours before testing. The flies were held from the tether with fine forceps and stimulated to fly by lack of tarsal contact, sometimes aided by gently blowing on them. After the indicated time of tethered flight (from 0.5 to 5.0 minutes) flies were dipped into a beaker of liquid nitrogen for one minute and then transferred to cold acetone and stored at −20°C overnight. The next morning the acetone was removed and the flies dried by centrifugation in a speedvac for one hour. The head, abdomen and legs were cut off and the desiccated thoraxes were stored in close containers with Drierite at −20°C until use.

Two-dimensional western blot analysis

Desiccated whole thoraces from D. melanogaster females were homogenized in 215 microliters of 8 M Urea, 2% CHAPS, 5% IPG buffer (BioRad), 0.2% dithiothreitol, and 1X protease inhibitors cocktail (CalBiochem), centrifuged at 8,000 RPM for 5 minutes at 25°C and the supernatant applied to 11 cm Ready Strip IPG gels (pH 4–7 linear gradient, BioRad). First and second dimension electrophoresis were carried out as described previously [13]. After second dimension, gels were blotted onto PVDF membrane and probed with anti-flightin polyclonal antibody (1:3000) followed by anti-rabbit Alexaflor 698 fluorescent antibody, as described [13]. Blots were scanned on an Odyssey fluorescent scanner (LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE) and analyzed with Phoretix 2D software (Nonlinear Dynamics, Durham, NC) as follows: Background subtraction was performed using the Mode of Non-spot method. Normalization was performed using the Total Spot Volume method that divides the volume of each spot by the total volume of all the spots for the gel and multiplies the result by 100 to give a percentage value (Spot percentage volume). Spots P1 and P2 do not always resolve as distinct spots and were treated as one spot for the purpose of this analysis. The numbers of blots analyzed for each time point were as followed: 0 sec, six; 30 sec, four; 90 sec, five; 180 sec, four; 300 sec, four. Only blots for which signal intensity was below a threshold saturation level, as determined from a serial dilution strip, were used for analysis.

Mass spectrometry

D. melanogaster IFM proteins were separated by 2-DE and stained with coomassie blue. Spots corresponding to flightin, identified from their molecular weight and pI, were cut out of the gel with a virgin razor blade and processed for linear ion trap MS/MS as follows: each gel spot was diced into 1 mm cubes, washed with water, destained with 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate/50% ACN, dehydrated with 100% ACN and subjected to in-gel digestion with sequencing grade modified trypsin (Promega, 6 ng/μL) in 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate overnight at 37 °C. Peptides were extracted with 50% ACN and 2.5% formic acid (FA) and then dried. Peptides were then resuspended in 2.5% ACN and 2.5% FA and loaded using a Micro AS autosampler (Thermo Electron, Waltham, MA) onto a microcapillary column packed with 12 cm of reversed-phase MagicC18 material (5 μm, 200 Å, Michrom Bioresources, Inc.). Elution was performed with a 5 35% ACN (0.1% FA) gradient over 60 min, after a 15 min isocratic loading at 2.5% ACN and 0.5% FA. The gradient was controlled by a Survey PumpPlus HPLC (Thermo Electron). Mass spectra were acquired in an LTQ-XL linear ion trap mass spectrometer (Thermo Electron) over the entire 75 min using 10 MS/MS scans following each survey scan. Raw data were searched with the Drosophila melanogaster flightin sequence using SEQUEST software with no enzyme requirement. The precursor mass tolerance was 2 Da. Differential modification of 16 Da (oxidation) on methionine residues and 71 Da (acrylamidation) on cysteine residues were permitted. Spectra for resulting tryptic phosphopeptides were manually validated and subjected to Ambiguity score (Ascore) analysis [20] to assess the strength of the identification and to assess phosphorylation site localization. Manual validation involved finding plausible solutions for all peaks not explained by b- and y-type ions, particularly by neutral losses of phosphoric acid, neutral losses of water or doubly-charged fragment ions.

Analysis of protein sequences

Flightin sequences were obtained from NCBI, UniProt, and Ensembl, as described previously [19]. Sequences from the following species were aligned using ClustalW: D. melanogaster (CG7445), D. simulans (GD12234), D. sechellia (GM14859), D. yakuba (GE22446), D. erecta (GG13353), D. ananassae (GF10833), D. pseudoobscura (GA22938), D. persimilis (GL25050), D. willistoni (GK18981), D. virilis (GJ11502), D. mojavensis (GI13378), D. grimshawi (GH14726).

The Selecton server (http://selecton.tau.ac.il/) was used to identify putative amino acid sites under positive selection using codon sequences of all 12 Drosophila species. A combined mechanistic and empirical codon (MEC) evolutionary model and M8a null model [21] was used.

Phosphorylation site predictions

Potential phosphorylation sites in flightin sequences were identified using NetPhos version 2.0 [22]. Sequences were also examined using Scansite (scansite.mit.edu) and Disorder enhanced phosphorylation predictor (DEPP; www.pondr.com).

Structural predictions

Predictions of intrinsic disorder were performed using several different predictors, including IUPred [23], PredictProtein [24], MobiDB [25], and the Predictor of natural disordered regions (PONDR-VXLT) [26].

Statistical Analysis

Our statistical analyses included two way ANOVA to evaluate D. melanogaster flightin phosphorylation in response to tethered flight. Subsequent analyses tested each flightin 2-DE spot identified in D. melanogaster across all time points using a two way ANOVA post hoc Bonferroni test. We also used student’s t-test to evaluate differences in the probability for intrinsic disorder of the flightin N-terminal region among twelve Drosophila species as well as the phosphorylated vs non-phosphorylated 2-DE spot intensity within D. melanogaster, independent of tethered flight.

RESULTS

Flightin phosphorylation in D. melanogaster is modulated during flight

To gain insight into the role of phosphorylation in flight muscle function, we measured the relative abundance of flightin isovariants (protein species) in non-flying and flying D. melanogaster by quantitative 2-DE western blotting. Tethered female flies were frozen in liquid nitrogen before flight initiation, and at four time points after flight initiation ranging from 30 seconds to 300 seconds. Figure 1 shows representative western blots of 2-DE for each time point. As described in a previous study, up to eleven protein species of flightin are present in the adult muscle [10]. For consistency, we followed the nomenclature for flightin spots proposed previously [10] in which the main spot that did not incorporate 32P in vivo during late pupal stages is labeled as N1, those that incorporated 32P are labeled P1 through P9.

Figure 1.

Western blots of 2-DE. Each panel is a representative western blot showing flightin protein species present during the indicated flight time, in seconds (top right corner). Spot assignation based on Vigoreaux & Perry [10]. For all blots, pH gradient is 7 to 4, left to right.

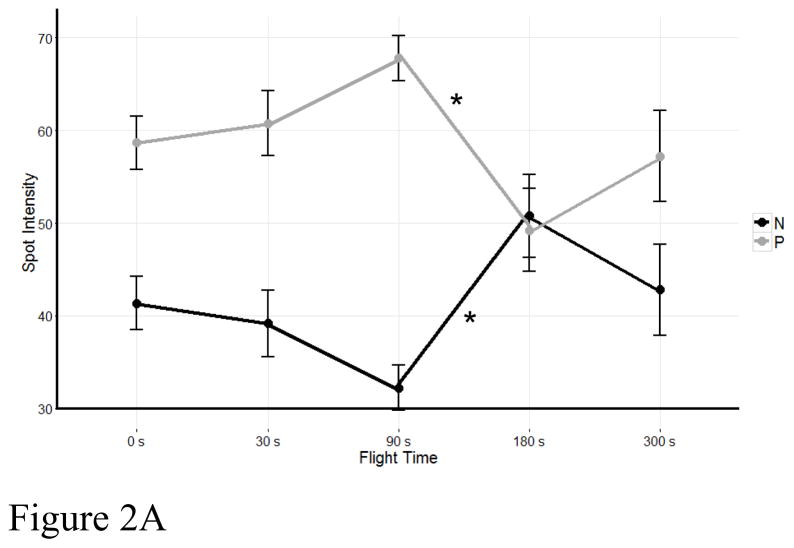

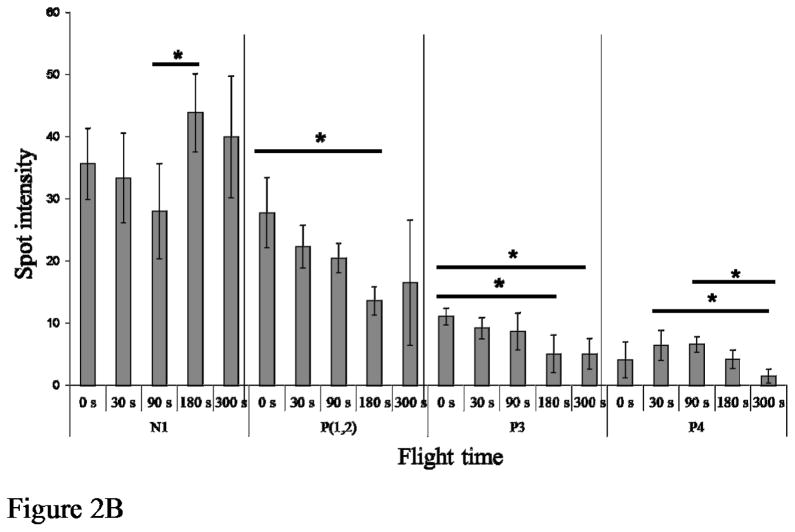

Our results revealed a significant decrease in P1-P9 spots between 90 and 180 seconds of flight (p<0.05) and a concomitant increase in the intensity of spot N1 (p<0.05) (Figure 2A). Bonferroni post hoc test showed a significant difference between time points 90 seconds and 180 seconds (p=0.020, α=0.05), but no difference between any other time points. There is no difference in the number of protein species detected in non-volant flies and flying flies irrespective of the flight time. Comparison of spot intensities across all time points revealed significant changes in N1 (p=0.043), P1/2 (p=0.008), P3 (p=0.003) and P4 (p= 0.015). Figure 2B shows dephosphorylation of spots P1/P2 and P3 begins with flight initiation and reaches a maximum at 3 minutes, precisely when the intensity of spot N1 is at a maximum. Additionally, dephosphorylation of spot P4 begins 30 seconds after flight initiation and reaches a maximum at 5 minutes. No significant changes were detected in the abundance of spots P5, P6, P7, P8 and P9.

Figure 2.

Quantitation of D. melanogaster flightin protein species expression during flight. (A) Sum of N and P protein species for each flight time where the X-axis represents time in seconds and the Y-axis represents the mean spot intensity value (in pixels) ± SE. Asterisks indicate a significant drop in P protein species intensity between 90 and 180 seconds of flight and a corresponding increase in intensity of N protein species. (B) Quantitation of individual flightin protein species across flight times. Only protein species whose intensity changed significantly during flight are shown. P1 and P2 are treated as one species as they do not always resolve into distinct spots. Asterisks indicate significant differences in spot intensity between time points within each bin as follows: N1, between 90 seconds and 180 seconds (p=0.046, α=0.05); P1/P2, between 0 seconds and 180 seconds (p=0.008, α=0.05); P3, between 0 seconds and 180 seconds (p=0.010, α=0.05), and between 0 seconds and 300 seconds (p=0.010, α=0.05); P4, between 30 seconds and 300 seconds (p=0.031, α=0.05), and between 90 seconds and 300 seconds (p=0.016, α=0.05).

Clustered phosphorylations in D. melanogaster flightin N-terminal region

To identify the phosphorylation sites that are modulated during flight in D. melanogaster, we conducted mass spectrometry of spots N1 through P9. Specifically, we were interested in identifying the phosphorylation sites that are modulated during flight that may account for the changes in intensity of protein species N1 and P1-P4. Each spot was analyzed individually by MS-MS and some phosphorylation sites were also confirmed by combining spots before the analysis. Sequence coverage ranged from 37% (spot P8) to 77% (spot P1/P2) (Supplementary Figure 1). Supplementary Figures 2–4 show representative spectra used to identify eight phosphorylation sites clustered within a 29 amino acid stretch in the N-terminal one third of the protein. These sites are serine 21, threonine 22, threonine 26, serine 31, serine 35, serine 38, serine 44, and threonine 49. Our analysis also confirmed two C-terminal sites previously identified, serine 139 and serine 141 (Supplementary Table SI and [14]). Because the C-terminal sites were confirmed in spots P5 and higher, they will not be considered further here.

Figure 3 is a summary of the phosphorylation sites that were identified in each gel spot. The most common phosphopeptides contained phospho-threonine 26 and phospho-threonine 49, the former detected in all spots except P9 and the latter detected in all spots except P4 and P8. The peptide region encompassing threonine 26 was not covered in spot P9 while the region encompassing threonine 49 was covered in spot P4 but not in spot P8 (Supplementary Figure 1 and Figure S4A). Surprisingly, both threonine 26 and threonine 49 are phosphorylated in N1, which had been shown previously not to incorporate 32P in vivo [10]. The third most abundant phosphopeptide contained phosphorylated serine 21. It was identified in all gel spots except N1, P1/2, P4, and P9. The non-phosphorylated peptide containing serine 21 was identified in N1, P1/P2 and P4, but not in P9 (Supplementary Figure 1 and Figure S2A). Two other sites were identified in single peptides. Phospho-threonine 22 was detected in spot P8 and phospho-serine 31 was detected in spot P3, despite coverage of this peptide in all spots except P9. Phosphorylation at three additional sites (serines 35, 38, and 44) were identified in multiple spots (Supplementary Figure S1 and S3B,C). Most spots contain mixtures of peptides with phosphorylated serine 44 and threonine 49 and phosphorylated threonine 49 alone. We did not detect peptides with phosphorylated serine 44 only. Additionally, the analysis revealed that each 2-DE spot consists of multiple protein species, as evidenced by the identification of unmodified peptides and their corresponding phosphopeptides (Supplementary Table S1).

Figure 3.

Summary of phosphorylation site identification in flightin protein species. The top diagram depicts the organization of flightin. The N-terminal region is denoted in gray, followed by a spacer region (green bar), the conserved WYR domain [19], and a C-terminal domain (black rectangle, [18]). Below it is the amino acid sequence from Lys 18 to Ala 51 (D. melanogaster numbering). Numbers in the table indicate how many peptides including each phosphorylated site were identified in the protein species listed on the left column.

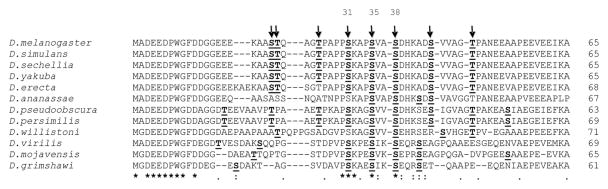

Conserved phosphorylation sites in fast evolving N-terminal region

To gain additional insight into the functional significance of clustered N-terminal phosphorylation of flightin, we compared the D. melanogaster flightin amino acid sequence to that of eleven other Drosophila species. Our previous analysis had shown the N-terminal region encompassing amino acids 1 through 65 is the least conserved region of the protein, with ~22% identity compared to > 76% for the rest of the protein (amino acids 66–182) [27]. The average amino acid identity of the eleven Drosophila orthologs to D. melanogaster flightin is 68% for amino acids 1–65 compared to 93% for amino acids 66–182 (Supplementary Table S2). Furthermore, analysis of synonymous and non-synonymous substitutions in flightin identified six putative positively selected sites, all within the N-terminal region (Supplementary Figure S5). These results indicate the flightin N-terminal region is evolving independently of the rest of the protein. Within the N-terminal region, fourteen amino acid positions are strictly conserved across twelve Drosophila species. Importantly, three of these amino acids are phosphorylated in D. melanogaster (serine 31, serine 35, and serine 38; Figure 4). Two other conserved sites, proline 30 and lysine 32 are adjacent to a phosphorylated amino acid in D. melanogaster and may be involved in protein kinase recognition. The observed pattern suggest that phosphorylation of the N-terminal region is a conserved feature despite the lack of overall amino acid sequence conservation. We investigated this supposition by NetPhos analysis of the sequences from the 11 non-melanogaster species. This program correctly predicted all 8 phosphorylation sites identified by mass spectrometry in D. melanogaster flightin. Several important results emanate from this analysis. First, all species are predicted to have multiple phosphorylation sites in the N-terminal region, ranging from 4 (D. annanassae) to 9 (D. pseudoobscura and D. persimilis). Second, threonine 49 is conserved in 9 of the 12 species (including D. melanogaster) and predicted to be phosphorylated in 8 of the species, the only exception being D. annanassae (Figure 4). In the three species where threonine 49 is not conserved (D. virilis, D. mojavensis, and D. grimshawi) it is replaced by an acidic amino acid. Thus, the negative charge is conserved at this site. Third, serine 35 and serine 38, two of the nine strictly conserved positions, are predicted to be phosphorylated in all species. Serine 31, also strictly conserved, is predicted to be phosphorylated in 10 of the 12 species, the exceptions being D. annanassae and D. willistoni. Fourth, serine 44 is predicted to be phosphorylated in all 8 species in which it is present. Four species which do not have serine at position 44 (D. willistoni, D. virilis, D. mojavensis, and D. grimshawi) have serines at adjacent positions that are predicted to be phosphorylated. Following D. melanogaster numbering, these serines correspond to positions 45 (D. willistoni) and 42 (D. virilis, D. mojavensis, and D. grimshawi). The three other phosphorylation sites, serine 21, threonine 22, and threonine 26 have less evident patterns of conservation. Serine 21 is predicted to be phosphorylated in all species in which it is conserved and in two species (D. pseudoobscura and D. persimilis) in which it is replaced by a threonine. Threonine 22 is predicted to be phosphorylated in all species in which it is conserved except D. mojavensis. Threonine 26 is conserved in 9 of the 12 species but predicted as a phosphorylation site in only six of the species (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Amino acid sequence alignment for the N-terminal region of flightin from 12 Drosophila species. Arrows indicate phosphorylation sites in D. melanogaster identified in this study. Numbers above arrows indicate positions of the three conserved serines (D. melanogaster numbering). Amino acids in bold and underlined are predicted to be phosphorylated (NetPhos 2.0). Note the correspondence between predictions and mapped sites in D. melanogaster is 100%. Symbols in the bottom row indicate strict identity (*) or conserved changes (:, .).

To test the predictions of NetPhos, we analyzed the flightin sequences using Scansite and Disorder Enhanced Phosphorylation Predictor (DEPP). Scansite did not predict any sites in D. melanogaster flightin when the search was executed at high stringency, and only one site (serine 31) when stringency was dialed down to medium. In contrast, DEPP predicted all serine and threonine residues within the N-terminal region of all 12 species as potential phosphorylation sites. Furthermore, all sites had a robust DEPP score ranging from 0.65 to 0.96 (residues with scores >0.5 are considered to be phosphorylated), with the exception of serine 20 in D. ananassae (0.57), serine 34 in D. pseudoobscura (0.57), serine 34 in D. persimilis (0.57), and threonine 20 in D. mojavensis (0.57) (Supplementary Table S3). The average and median for all sites was 0.79. Because DEPP relies on disorder propensity to predict phosphorylation sites, we next investigated the disorder potential for N-terminal flightin sequences.

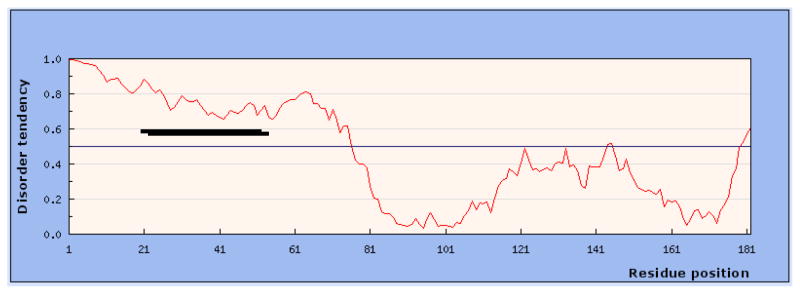

Prediction of Flightin N-terminal disorder

Together with the high DEPP scores, the low amino acid sequence conservation of the N-terminal region, and the lack of homology to any known protein motif raise the intriguing possibility that this region may lack an ordered structure. To investigate this possibility, we queried the MobiDB database of protein disorder [25] for flightin resulting in 20 hits (see below). For D. melanogaster flightin, the consensus prediction from 10 predictors (including DisEMBL, ESpritz, GlobPlot, IUPRED, JRONN, VSL2b) is a disordered N-terminal region (amino acids 1–77) and two short disordered segments (amino acids 141–145 and 179–182) in the C-terminal region. Seven of the ten algorithms predicted a continuous intrinsically disordered region (IDR) extending from amino acid 1 to 60 (the other three predicted short helical segments interrupting a largely disordered region). To reduce the potential for type 1 errors, we extended the analysis to programs that utilize different algorithms. These included the Meta-Disorder predictor (www.predictprotein.org; [24]) and predictors based on the chemical and physical properties of amino acids, including charge-hydropathy plot [28] and GlobPlot [29]. All programs were consistent in predicting a disordered N-terminal region (data not shown).

To investigate the N-terminal region in more detail, we analyzed the flightin sequence using the IUPred web server (http://iupred.enzim.hu/) which utilizes an algorithm that estimates inter-residue interaction energy [23]. As shown in Figure 5 for D. melanogaster, the N-terminal region of flightin has a high probability of disorder, consistent with predictions from all other algorithms. The long disorder tendency score for the N-terminal region (amino acids 1–65) is 0.842 compared to 0.367 for the region extending from amino acids 66 to 182. When these regions are evaluated separately, the values increase for the N-terminal (0.948) and decrease for the rest of the protein (0.303). Analysis of the flightin sequence for the other 11 Drosophila species returned similar predictions that were confirmed with the Predictor of natural disordered regions (PONDR) (Table I).

Figure 5.

Analysis of D. melanogaster flightin with IUPred prediction method. Residues with scores greater than 0.5 (horizontal line) are predicted to be disordered. By this criteria, the entire N-terminal region has a high probability of intrinsic disorder. A similar result was obtained for orthologs from eleven other Drosophila species. Bold horizontal line indicates region of clustered phosphorylations.

Table I.

Disorder Prediction Scores for Flightin N-terminal Region

| Species | PONDR-VLXT | IUPRED |

|---|---|---|

| D. melanogaster | 0.921 | 0.948 |

| D. simulans | 0.921 | 0.948 |

| D. sechellia | 0.921 | 0.948 |

| D. yakuba | 0.916 | 0.937 |

| D. erecta | 0.901 | 0.936 |

| D. ananassae | 0.944 | 0.966 |

| D. pseudoobscura | 0.811 | 0.827 |

| D. persimilis | 0.811 | 0.827 |

| D. willistoni | 0.925 | 0.951 |

| D. virilis | 0.904 | 0.971 |

| D. mojavensis | 0.931 | 0.984 |

| D. grimshawi | 0.886 | 0.933 |

Numbers represent average scores for region 1–65 (D. melanogaster numbering).

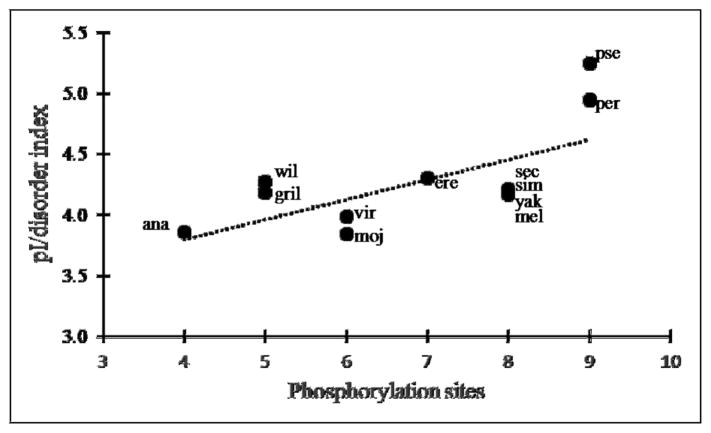

In addition to high phosphorylation potential, disordered regions are characterized by a high density of charged amino acids [30]. The flightin N-terminal region in all Drosophila species is polyanionic. The pI for this region ranges from 3.73 (D. ananassae) to 4.34 (D. pseudoobscura), with an average of 3.97 ± 0.15 and a net charge of −12.8 ± 1.4 for the 12 species. A comparison of the number of predicted phosphorylation sites to the pI of the disordered region revealed a linear relationship: fewer potential phosphorylation sites are found in orthologs with lower intrinsic pI than in orthologs with higher intrinsic pI. This pattern raises the possibility that phosphorylation acts to increase disorder by imparting additional negative charges. A corollary of this prediction is that a direct correlation exists between the number of phosphorylation sites and the disorder tendency. As seen in Figure 6, the ratio of pI to disorder tendency correlates linearly with phosphorylation potential. Thus, phosphorylation acts as an equalizer of disorder by contributing negative charges in orthologs with higher intrinsic pI.

Figure 6.

Relation between number of predicted phosphorylation sites and the ratio of pI to disorder index, calculated by IUPRED. Each dot represents a Drosophila species, as follows: ana (D. ananassae), wil (D. willistoni), gri (D. grimshawi), vir (D. virilis), moj (D. mojavensis), ere (D. erecta), sec (D. sechellia), sim (D. simulans), mel (D. melanogaster), yak (D. yakuba), pse (D. pseudoobscura), per (D. persimilis). The dotted line represents the linear best fit (R2=0.44).

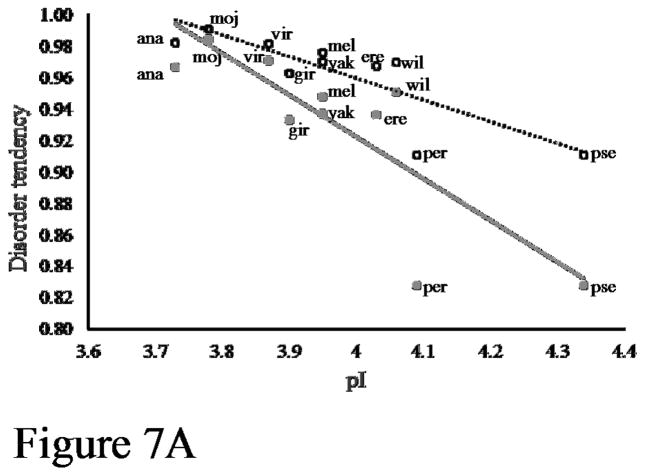

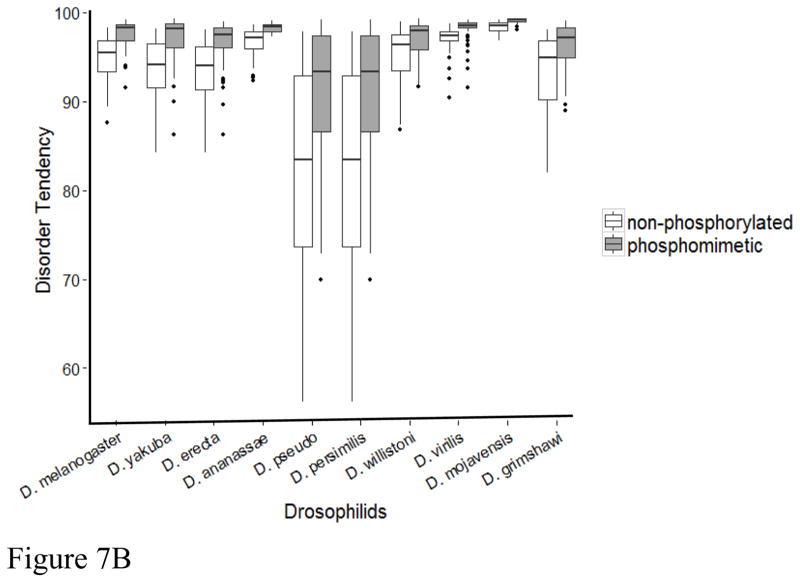

To test the hypothesis that phosphorylation acts to increase predicted disorder, we next determined the disorder tendency of phosphomimetics for each of the flightin orthologs by replacing mapped and predicted phosphorylation sites with glutamic acid. Three consistent trends emerged from this analysis. First, all phosphomimetics had a higher predicted disorder tendency than their non-phosphorylated counterparts (Figure 7A). When these substitutions are made disorder tendency increases significantly, on average, by 4% (Figure 7B). Second, the increase in mimetic phosphorylation-promoted disorder is proportionally greater in orthologs with higher intrinsic pI than in orthologs with lower intrinsic pI (Figure 7A). Third, the increase in phosphorylation-promoted disorder is proportionally greater in orthologs with lower intrinsic disorder and higher number of phosphorylation sites (Supplementary Figure S6). For example, the largest increase in phosphorylation-promoted disorder (10%) occurred in D. persimilis and D. pseudoobscura, the two orthologs with the highest number of phosphorylation sites (9) and the lowest intrinsic disorder (0.827). Altogether, these results suggest that phosphorylation-promoted increase in disorder tendency is an evolutionary conserved mechanism in Drosophila flightin.

Figure 7.

Phosphorylation increases disorder tendency. (A) Each pair of vertically aligned symbols represent the non-phosphorylated (filled symbol) and phosphomimetic (open symbol) N-terminal region from the indicated species (see Figure 6 legend for abbreviations. D. simulans and D. sechellia are superimposed on D. melanogaster). Broken lines represent best fit for non-phosphorylated (blue, R2 = 0.677) and phosphorylated (red, = 0.680) orthologs. (B) Box plots showing significant difference in disorder index between non-posphorylated and phosphomimetic pairs for all Drosophila species. Disorder index calculated by IUPRED.

Conserved Flightin N-terminal region features in other insect species

In addition to Drosophila, flightin has been identified in more than 70 other species of hexapods and crustaceans based on the conservation of the WYR domain [19], predicted to have a globular structure that is largely alpha-helical. The N-terminal region is highly variable in sequence and length, ranging from 8 to 77 amino acids. Nevertheless, all sequences examined shared common features, namely a high content of acidic amino acids and an alanine-proline rich region [19]. We queried the MobiDB database for flightin to determine if a tendency for disorder is common among flightin orthologs outside Drosophila. The query returned flightin sequences from 20 species, all with a predicted disordered N-terminal region. In all but two cases, the prediction for disorder was 100% for the entire region. The exceptions were Lethocerus (waterbug) at 98%, i.e., one amino acid in the sequence with a low disorder prediction score, and Danaus (monarch butterfly) in which the disordered N-terminal region is interrupted by a short ordered stretch of amino acids. For all sequences in the database, the N-terminal region was either the only or the longest predicted disordered region in the protein.

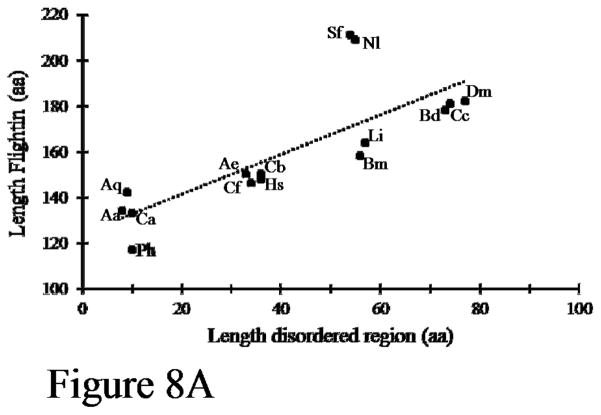

Two other features of flightin show patterns of evolutionary conservation. First, the length of the disordered region is directly proportional to the length of the total protein (Figure 8A). Intriguingly, the length of the disordered regions cluster as multiples of 9. Mosquitoes, midges, and the human louse have an average length of 9 amino acids, ants have an average length of 35 amino acids, true bugs (hemipterans) and silkmoth have an average length of 56 amino acids, and flies have an average length of 75 amino acids. Second, all orthologs contain a “spacer” sequence between the end of the disordered region and the beginning of the conserved WYR domain. The length of the spacer is inversely proportional to the length of the disordered region (Figure 8B). However, the total length of disordered region plus spacer is neither constant nor proportionally related to the length of the protein.

Figure 8.

Properties of the flightin N-terminal region. (A) The length (number of amino acids) of the N-terminal disordered region is proportional to the length of the protein. Each dot represents one species ortholog, as follows: Dm, Drosophila melanogaster; Cc, Ceratitis capitate; Bd, Bactrocera dorsalis; Li, Lethocerus indicus; Bm, Bombyx mandarina & mori; Nl, Nilaparvata lugens; Sf, Sogatella furcifera; Cb, Cerapachys biroi; Hs, Harpegnathos saltator; Cf, Camponotus floridanus; Ae, Acromyrmex echinatior; Ph, Pediculus humanus; Ca, Corethrella appendiculata; Aq, Anopheles aquasalis; Aa, Aedes albopictus. Dotted line represents linear best fit (R2 = 0.613). Note that the length of the disordered region clusters in multiples of 9. (B) Length of the linker region increases as the length of the disordered region decreases.

DISCUSSION

In this study we provided evidence that flightin is sequentially phosphorylated in the N-terminal region and that phosphorylation changes dynamically during flight in Drosophila melanogaster. Comparison of flightin phosphorylation sites across twelve Drosophila species revealed three patterns of selection: (i) sites that are constrained evolutionarily and remain invariant (serine 31, serine 35, and serine 38); (ii) a non-identical site with a conserved charge character (threonine 49); and, (iii) sites that are constrained within specific clades (serine 21, threonine 22, threonine 26, and serine 44). Sequence analyses of the flightin N-terminal region consistently predicted this region to be intrinsically disordered. Further increases in intrinsic disorder propensity of flightin the N-terminal region occur with phosphorylation through negative charge augmentation.

Phosphorylation and protein species

Previously, we had shown that phosphorylation of flightin in D. melanogaster increases dramatically and sequentially in eclosing pupa and pharate adults, reaching a near steady state about the time the fly acquires flight competency [10]. We extend these observations by demonstrating that flightin phosphorylation changes dynamically during flight with the largest change occurring midway through the flight sequence between 90 and 180 seconds. We speculate changes in flightin phosphorylation reflect adjustment in flight behavior, e.g., a switch to steady flight, given that Drosophila is known to modulate wing stroke kinematics (amplitude and frequency) to alter the speed and direction of flight [31]. Existing data on wing kinematics demonstrate these processes are likely regulated by activation of control (direct flight) muscles [32]. Our results provide evidence supporting an alternative mechanism whereby wing beat frequency is modulated dynamically through changes in IFM stiffness.

Flightin increases the flexural rigidity of thick filaments and contributes to fiber elastic modulus [15, 17]. We hypothesize that phosphorylation-dephosphorylation of flightin influences thick filament stiffness and IFM viscoelasticity and provides for a rapid, in-flight-time mechanism for adapting wing beat frequency within the constraints of the resonant frequency under which the flight system operates. Additionally, reversible phosphorylation allows for within species individual variability in wing beat frequency, which can differ by as much as 15–20% (e.g., 185–225 Hz in “wild-type” tethered D. melanogaster). As wing beat frequency scales inversely with body mass [6], the within-species range in wing beat frequency may reflect differences in body size and load, as has been documented in bumblebees [33]. Test of this hypothesis awaits further investigation, such as functional studies that can simultaneously track wing kinematics, flight aerodynamics, and protein phosphorylation on a millisecond timescale.

The identification of phosphopeptides in the N1 protein species was unexpected given that our previous in vivo analysis did not identify phosphorylation of N1 during the pupal-to-adult transition [10]. A possible explanation is that threonine 26 and threonine 49 are phosphorylated constitutively earlier in flight muscle development, perhaps by the same proline-directed kinase (e.g., p38MAPK) that recognizes the motif AGTPA surrounding the two sites. Consistent with this hypothesis is the result that peptides containing phospho-threonine 26 and phospho-threonine 49 were the most commonly identified phosphopeptides among all 2-DE spots. The conservation of threonine 49 in all species of the subgenus Sophophora (9 of 12 Drosophila species studied here) and its substitution with aspartic or glutamic acid in three other Drosophila species (virilis, mojavensis, and grimshawi) lends validity to the argument that a permanent negative charge at this site is an essential determinant of the conformational state of the N-terminal region. The only species within the subgenus Sophophora for which threonine 49 is not predicted to be phosphorylated (D. ananassae) also lacks the motif AGTPA. A similar, albeit less evident pattern, is observed for threonine 26. In four of the six species in which threonine 26 is either absent or not predicted to be phosphorylated (willistoni, virilis, mojavensis, and grimshawi), it is adjacent to an aspartic acid not present in the species with predicted phospho-threonine. Two other species, D. erecta and D. ananassae, have threonine at positions 26 and 27, respectively, that are not predicted to be phosphorylated. These two species also lack the conserved AGTPA motif.

The results showing that each 2-DE spot consists of multiple protein species, together with the lower abundance of spots with the most acidic pI (i.e., higher spot number) makes it difficult to pinpoint the precise order of phosphorylation. Additionally, we cannot discount the possibility that some phosphopeptides are contaminants (“bleed-through”) from adjacent proteins species, notwithstanding the great care taken in isolating clearly well resolved spots. Despite these caveats, there is strong evidence of a trend towards increased phosphorylation as the spots’ pI decrease, consistent with the sequential order in which the spots appear during in vivo muscle development.

Our results make it possible to partially deduce the order in which some of the sites are phosphorylated in vivo in D. melanogaster. We propose that serine 44 is the next site to be phosphorylated after threonine 26 and threonine 49 based on its presence in spots P1/P2 and the absence of peptides in which phosphorylation of serine 44 is detected in the absence of phospho-threonine 49. Spot P3 contains phospho-serine at sites 21, 31, 35, and 38. Two of these sites, serine 21 and serine 35, have a similar basophilic kinase recognition sequence (KAxS) as serine 44 and represent good candidates for being next in the sequence. It is not possible to discern the phosphorylation event sequence between serine 35 and serine 38 since the two sites are only unambiguously identified in spot P7, but one or the other is first phosphorylated in spot P3. The detection of phospho-serine 31 in a single peptide suggests this is a transient/high turnover phosphorylation event. Finally, phosphorylation at threonine 22, a possible substrate for an ATM-like kinase, is detected only in spot P8 indicating this is a late event in the phosphorylation sequence. Taken together, we propose that dephosphorylation of serine 31 and serine 44 are primarily responsible for the decrease in protein species P1-P4 and concomitant increase in protein species N1 that occurs during flight.

Conserved features of the N-terminal region

The analysis of the N-terminal sequence using multiple bioinformatics approaches consistently predicted, with very high probability, the intrinsically disordered structure of this region. Robust predictive scores were obtained with several different machine learned algorithms (e.g., PONDR, DISOPRED, DisEMBL), non-machine based methods that rely on statistical calculation of amino acids contacts (e.g., HCA, IUPRED), and predictors based on amino acid propensities (e.g, Globplot, charge-hydropathy plots). Based on the consensus from all in silico approaches, we conclude that the N-terminal region of flightin is an IDR. The finding that the N-terminal region harbors a cluster of phosphorylation sites is consistent with its designation as an IDR, as these regions are known to be frequent targets for protein phosphorylation and other post-translational modifications [30, 34]. Additionally, IDR generally evolve at a faster rate than ordered regions within the same protein families [35], analogous to what is observed in flightin when comparing the N-terminal region to the adjoining WYR domain. The combined properties of conserved intrinsic disorder and low amino acid sequence identity places flightin in the category of “flexible disorder” proteins [36], a group that includes entropic chains. Entropic chains have been characterized in several cytoskeletal and muscle proteins where they exhibit properties of mechanical elements such as springs and spacers [37, 38].

What does an intrinsically disordered N-terminal region with multiple phosphorylation sites tells us about the function of flightin? Flightin binds the myosin coiled-coil, the “rod” domain responsible for polymerization of myosin [16]. The interaction of flightin with the myosin rod contributes as much as 45% of the total thick filament bending stiffness [15]. Indeed, in the absence of flightin thick filaments are not only more susceptible to proteolytic degradation [9, 39], an indication that flightin is essential for thick filament stability, but also are too compliant to sustain stretch activation and produce power for flight [17]. Due to the polyanionic nature of the N-terminal region and of the myosin rod domain, it is more likely that the former protrudes out of the latter, rather than lay along its side. In this manner, the flightin N-terminal region acts as an entropic linker between coiled-coils forming the backbone of the thick filament. Disorder affords the ability to bind with high specificity and low affinity [40] and phosphorylation allows for structural changes without protein complex dissociation [41], properties that are advantageous, from an energy cost perpsective, for a highly dynamic system such as a muscle undergoing repeated contractions every few milliseconds. Different states of phosphorylation dictate differences in extensibility, compressibility or “springiness” of the coiled-coil connectors. As such, the local effect of phosphorylation of the N-terminal region influence the bending stiffness of the thick filament, the viscoelastic properties of the muscle fiber, the power output of the muscle, and ultimately the flight behavior of the animal.

Recent findings highlight the important role of the IFM in non-flight behaviors that involve wing movement, such as courtship in Drosophila. Mutations of the myosin regulatory light chain (DMLC2) were shown to affect courtship song properties in ways that suggest DMLC2 fulfills different roles in song production than in flight [42]. While the role of flightin in courtship song production awaits further investigation, it is tempting to speculate that phosphorylation of the N-terminal region contributes to species-specific differences in song properties, such as the frequency of the pulse song and sine song. A prominent role in defining courtship song uniqueness among Drosophila species could explain the poor amino acid sequence conservation (i.e., faster rate of evolution) and the presence of putative positive selected sites in the N-terminal region, attributes that characterize genes under sexual selection such as those that define courtship song components [43, 44].

CONCLUSION

The N-terminal region of flightin is an intrinsically disordered region characterized by low amino acid sequence conservation and a high density of phosphorylation sites whose absolute number is dictated by the intrinsic charge of the region. The length of the N-terminal region is variable and proportional to the full length of the protein and to the linker region. These patterns of interdependency are indicative of strong evolutionary selection for structural and functional attributes that are not strictly constrained by a precise sequence of amino acids.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Table S1. Flightin phosphopeptides identified from 2-DE gel spots by LC MS/MS.

Supplementary Table S2. Flightin ortholog amino acid identity to D. melanogaster flightin.

Supplementary Table S3. DEPP phosphorylation site prediction for 12 Drosophila flightin orthologs.

Figure S1. Sequence coverage for each flightin spot. Identified peptides are highlighted in yellow. Coverage ranged from 37% (spot P8) to 77% (spot P1/P2). Yellow highlight indicates confident coverage by tryptic peptides. Red indicates confidently identified phosphorylation sites. Blue indicates confident phosphorylation but ambiguity in the site assignment. Thus, for spot P3 one of the sites may not be correct, but at least two of the three are correct. Similarly for spot P5, only one of the two sites is correct.

Figure S2. Low-energy CID MS/MS spectrum acquired as described in Materials & Methods depicting unphosphorylated and phosphorylated peptides containing sites S21, T22, T26, S31. Predicted masses are colored blue (b-type ions) or red (y-type ions) if identified in the spectrum.

Figure S3. Low-energy CID MS/MS spectrum acquired as described in Materials & Methods depicting unphosphorylated and phosphorylated peptides containing sites S21, T22, T26, S31, S35, S38. Predicted masses are colored blue (b-type ions) or red (y-type ions) if identified in the spectrum.

Figure S4. Low-energy CID MS/MS spectrum acquired as described in Materials & Methods depicting unphosphorylated and phosphorylated peptides containing sites S44, T49. Predicted masses are colored blue (b-type ions) or red (y-type ions) if identified in the spectrum.

Figure S5. Selection regimes acting on flightin. Putative sites under positive selection (dN/dS>1) are highlighted in yellow. Shown here is the flightin sequence from D. melanogaster. Results were obtained with the Selecton server (http://selecton.tau.ac.il/) using as input the flightin sequence from 12 Drosophila species. The N-terminal region (aa 1–65, boxed) has an average evolutionary rate of 0.4 compared to 0.08 for region aa 66–182.

Figure S6. Phosphorylation increases disorder tendency. For each species, number in parenthesis indicate phosphorylation sites predicted by NetPhos. Blue bars, non-phosphorylated N-terminal region; red bars, phosphomimetic N-terminal region. Note than phosphorylation compensation is greater in sequences with lower disorder tendency, as shown by the percent increase in disorder. Disorder index calculated by IUPRED.

SIGNIFICANCE.

Flying insects constitute a majority among Arthropoda, the most diverse and species rich phylum. Understanding the underlying reasons for this success requires elucidation of the molecular mechanisms that drive the evolution of the flight muscle. The results presented here provide insight into the structural constraints that dictate the evolution of flightin, an essential protein of the insect flight muscle machinery.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NSF grants MCB 1050834 and IOB 0718417 to J.O.V. Mass spectrometry was conducted at the Vermont Genetics Network Proteomics Facility, supported by an Institutional Development Award (IDeA) from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under grant number P20GM103449. DL was supported in part by USDE Ronald E. McNair Post-Baccalaureate Achievement Program grant # P217A030288. We thank members of the Vigoreaux lab for many helpful discussions, especially Felipe Soto and Samya Chakravorty. The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of NSF, NIGMS or NIH.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Grimaldi D, Engel MS. Evolution of the insects. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilson EO. The diversity of life. New York: W. W. Norton & Company; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brodsky AK. The evolution of insect flight. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cullen MJ. The distribution of asynchronous muscle in insects with special reference to the Hemiptera: an electron microscope study. J Ent. 1974;49A:17–41. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith DS. The structure of insect muscles. In: King RC, Akai H, editors. Insect ultrastructure. New York: Academic Press; 1984. pp. 111–50. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dudley R. The biomechanics of insect flight. Princeton: Princeton University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hunter JP. Key innovations and the ecology of macroevolution. Trends in ecology & evolution. 1998;13:31–6. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5347(97)01273-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vigoreaux JO, Saide JD, Valgeirsdottir K, Pardue ML. Flightin, a novel myofibrillar protein of Drosophila stretch-activated muscles. J Cell Biol. 1993;121:587–98. doi: 10.1083/jcb.121.3.587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reedy MC, Bullard B, Vigoreaux JO. Flightin is essential for thick filament assembly and sarcomere stability in Drosophila flight muscles. J Cell Biol. 2000;151:1483–99. doi: 10.1083/jcb.151.7.1483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vigoreaux JO, Perry LM. Multiple isoelectric variants of flightin in Drosophila stretch-activated muscles are generated by temporally regulated phosphorylations. J Muscle Res Cell Motil. 1994;15:607–16. doi: 10.1007/BF00121068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nongthomba U, Cummins M, Clark S, Vigoreaux JO, Sparrow JC. Suppression of muscle hypercontraction by mutations in the myosin heavy chain gene of Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 2003;164:209–22. doi: 10.1093/genetics/164.1.209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vigoreaux JO, Hernandez C, Moore J, Ayer G, Maughan D. A genetic deficiency that spans the flightin gene of Drosophila melanogaster affects the ultrastructure and function of the flight muscles. J Exp Biol. 1998;201:2033–44. doi: 10.1242/jeb.201.13.2033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barton B, Ayer G, Heymann N, Maughan DW, Lehmann FO, Vigoreaux JO. Flight muscle properties and aerodynamic performance of Drosophila expressing a flightin transgene. The Journal of experimental biology. 2005;208:549–60. doi: 10.1242/jeb.01425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barton B, Ayer G, Maughan DW, Vigoreaux JO. Site directed mutagenesis of Drosophila flightin disrupts phosphorylation and impairs flight muscle structure and mechanics. J Muscle Res Cell Motil. 2007;28:219–30. doi: 10.1007/s10974-007-9120-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Contompasis JL, Nyland LR, Maughan DW, Vigoreaux JO. Flightin is necessary for length determination, structural integrity, and large bending stiffness of insect flight muscle thick filaments. Journal of molecular biology. 2010;395:340–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ayer G, Vigoreaux JO. Flightin is a myosin rod binding protein. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2003;38:41–54. doi: 10.1385/CBB:38:1:41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Henkin JA, Maughan DW, Vigoreaux JO. Mutations that affect flightin expression in Drosophila alter the viscoelastic properties of flight muscle fibers. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2004;286:C65–C72. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00257.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tanner BC, Miller MS, Miller BM, Lekkas P, Irving TC, Maughan DW, et al. COOH-terminal truncation of flightin decreases myofilament lattice organization, cross-bridge binding, and power output in Drosophila indirect flight muscle. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2011;301:C383–91. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00016.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Soto-Adames FN, Alvarez-Ortiz P, Vigoreaux JO. An evolutionary analysis of flightin reveals a conserved motif unique and widespread in Pancrustacea. J Mol Evol. 2014;78:24–37. doi: 10.1007/s00239-013-9597-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beausoleil SA, Villen J, Gerber SA, Rush J, Gygi SP. A probability-based approach for high-throughput protein phosphorylation analysis and site localization. Nature biotechnology. 2006;24:1285–92. doi: 10.1038/nbt1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stern A, Doron-Faigenboim A, Erez E, Martz E, Bacharach E, Pupko T. Selecton 2007: advanced models for detecting positive and purifying selection using a Bayesian inference approach. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:W506–11. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blom N, Gammeltoft S, Brunak S. Sequence and structure-based prediction of eukaryotic protein phosphorylation sites. Journal of molecular biology. 1999;294:1351–62. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dosztanyi Z, Csizmok V, Tompa P, Simon I. IUPred: web server for the prediction of intrinsically unstructured regions of proteins based on estimated energy content. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:3433–4. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yachdav G, Kloppmann E, Kajan L, Hecht M, Goldberg T, Hamp T, et al. PredictProtein--an open resource for online prediction of protein structural and functional features. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:W337–43. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Potenza E, Di Domenico T, Walsh I, Tosatto SC. MobiDB 2.0: an improved database of intrinsically disordered and mobile proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:D315–20. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Romero P, Obradovic Z, Li X, Garner EC, Brown CJ, Dunker AK. Sequence complexity of disordered protein. Proteins. 2001;42:38–48. doi: 10.1002/1097-0134(20010101)42:1<38::aid-prot50>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tanner BC, Miller MS, Miller BM, Lekkas P, Irving TC, Maughan DW, et al. C-terminal truncation of flightin decreases myofilament lattice organization, cross-bridge binding, and power output in Drosophila indirect flight muscle. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2011 doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00016.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Uversky VN, Gillespie JR, Fink AL. Why are “natively unfolded” proteins unstructured under physiologic conditions? Proteins. 2000;41:415–27. doi: 10.1002/1097-0134(20001115)41:3<415::aid-prot130>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Linding R, Russell RB, Neduva V, Gibson TJ. GlobPlot: Exploring protein sequences for globularity and disorder. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:3701–8. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Habchi J, Tompa P, Longhi S, Uversky VN. Introducing protein intrinsic disorder. Chem Rev. 2014;114:6561–88. doi: 10.1021/cr400514h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lehmann FO, Dickinson MH. The control of wing kinematics and flight forces in fruit flies (Drosophila spp.) The Journal of experimental biology. 1998;201:385–401. doi: 10.1242/jeb.201.3.385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lehmann FO, Gotz KG. Activation phase ensures kinematic efficacy in flight-steering muscles of Drosophila melanogaster. J Comp Physiol A. 1996;179:311–22. doi: 10.1007/BF00194985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ellington CP. The novel aerodynamics of insect flight: applications to micro-air vehicles. The Journal of experimental biology. 1999;202(Pt 23):3439–48. doi: 10.1242/jeb.202.23.3439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Iakoucheva LM, Radivojac P, Brown CJ, O’Connor TR, Sikes JG, Obradovic Z, et al. The importance of intrinsic disorder for protein phosphorylation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:1037–49. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brown CJ, Takayama S, Campen AM, Vise P, Marshall TW, Oldfield CJ, et al. Evolutionary rate heterogeneity in proteins with long disordered regions. J Mol Evol. 2002;55:104–10. doi: 10.1007/s00239-001-2309-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bellay J, Han S, Michaut M, Kim T, Costanzo M, Andrews BJ, et al. Bringing order to protein disorder through comparative genomics and genetic interactions. Genome Biol. 2011;12:R14. doi: 10.1186/gb-2011-12-2-r14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tompa P. The interplay between structure and function in intrinsically unstructured proteins. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:3346–54. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.03.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee EH, Hsin J, von Castelmur E, Mayans O, Schulten K. Tertiary and secondary structure elasticity of a six-Ig titin chain. Biophysical journal. 2010;98:1085–95. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.12.4192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kronert WA, O’Donnell PT, Fieck A, Lawn A, Vigoreaux JO, Sparrow JC, et al. Defects in the Drosophila myosin rod permit sarcomere assembly but cause flight muscle degeneration. Journal of molecular biology. 1995;249:111–25. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Uversky VN. Intrinsic disorder-based protein interactions and their modulators. Current pharmaceutical design. 2013;19:4191–213. doi: 10.2174/1381612811319230005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Colson BA, Gruber SJ, Thomas DD. Structural dynamics of muscle protein phosphorylation. J Muscle Res Cell Motil. 2012;33:419–29. doi: 10.1007/s10974-012-9317-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chakravorty S, Vu H, Foelber V, Vigoreaux JO. Mutations of the Drosophila myosin regulatory light chain affect courtship song and reduce reproductive success. PloS one. 2014;9:e90077. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0090077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vanaphan N, Dauwalder B, Zufall RA. Diversification of takeout, a male-biased gene family in Drosophila. Gene. 2012;491:142–8. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2011.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Markow TA, O’Grady PM. Evolutionary genetics of reproductive behavior in Drosophila: connecting the dots. Annu Rev Genet. 2005;39:263–91. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.39.073003.112454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Table S1. Flightin phosphopeptides identified from 2-DE gel spots by LC MS/MS.

Supplementary Table S2. Flightin ortholog amino acid identity to D. melanogaster flightin.

Supplementary Table S3. DEPP phosphorylation site prediction for 12 Drosophila flightin orthologs.

Figure S1. Sequence coverage for each flightin spot. Identified peptides are highlighted in yellow. Coverage ranged from 37% (spot P8) to 77% (spot P1/P2). Yellow highlight indicates confident coverage by tryptic peptides. Red indicates confidently identified phosphorylation sites. Blue indicates confident phosphorylation but ambiguity in the site assignment. Thus, for spot P3 one of the sites may not be correct, but at least two of the three are correct. Similarly for spot P5, only one of the two sites is correct.

Figure S2. Low-energy CID MS/MS spectrum acquired as described in Materials & Methods depicting unphosphorylated and phosphorylated peptides containing sites S21, T22, T26, S31. Predicted masses are colored blue (b-type ions) or red (y-type ions) if identified in the spectrum.

Figure S3. Low-energy CID MS/MS spectrum acquired as described in Materials & Methods depicting unphosphorylated and phosphorylated peptides containing sites S21, T22, T26, S31, S35, S38. Predicted masses are colored blue (b-type ions) or red (y-type ions) if identified in the spectrum.

Figure S4. Low-energy CID MS/MS spectrum acquired as described in Materials & Methods depicting unphosphorylated and phosphorylated peptides containing sites S44, T49. Predicted masses are colored blue (b-type ions) or red (y-type ions) if identified in the spectrum.

Figure S5. Selection regimes acting on flightin. Putative sites under positive selection (dN/dS>1) are highlighted in yellow. Shown here is the flightin sequence from D. melanogaster. Results were obtained with the Selecton server (http://selecton.tau.ac.il/) using as input the flightin sequence from 12 Drosophila species. The N-terminal region (aa 1–65, boxed) has an average evolutionary rate of 0.4 compared to 0.08 for region aa 66–182.

Figure S6. Phosphorylation increases disorder tendency. For each species, number in parenthesis indicate phosphorylation sites predicted by NetPhos. Blue bars, non-phosphorylated N-terminal region; red bars, phosphomimetic N-terminal region. Note than phosphorylation compensation is greater in sequences with lower disorder tendency, as shown by the percent increase in disorder. Disorder index calculated by IUPRED.