Abstract

Heavy menstrual bleeding (HMB) has significant adverse effects on the quality of life of many women, placing an economic burden on both health services and society at large. Thus, it is essential that all women with HMB have easy access to the proper diagnostic and therapeutic work-up in an outpatient fashion, avoiding the more time-consuming inpatient management. This new outpatient approach for HMB is one of the latest development of gynecological practice and can offer both diagnostic and therapeutic procedures. This manuscript aims to show the current possibilities of the modern management of HMB, which can be safely and effectively accomplished in the outpatient setting: global and directed endometrial biopsy, levonorgestrel intrauterine system insertion as well as minimally invasive surgical procedures (encompassing a variety of operative hysteroscopic procedures and second-generation endometrial ablation) are described below.

Keywords: ambulatory setting, endometrial biopsy, heavy menstrual bleeding, levonorgestrel intrauterine system, office operative hysteroscopy, second-generation endometrial ablation

Heavy menstrual bleeding (HMB) is common, accounting for up to a third of gynaecological hospital outpatient visits [1]. The condition is generally not life threatening but is important for several reasons; HMB has an adverse effect on quality of life in many women and excessive menstrual blood loss can be associated with anemia [1]. Furthermore, psychological impairment has been reported with increased irritability, moodiness and low energy, leading to social embarrassment, sexual compromise and alteration in lifestyle. HMB affects women of working age and it has been reported that absenteeism and a reduction in work capacity occurs in up to 20% of women. Thus, HMB places an economic burden on both health services and society at large [2–4].

HMB has several underlying causes and the PALM COEIN classification [5] has recently been proposed to facilitate standardized and generalizable reporting of interventions and outcomes. Both dysfunctional uterine bleeding and HMB, thought to be due to intrauterine pathologies including fibroids, polyps and endometrial hyperplasia, are amenable to safe, convenient, effective and cost-effective diagnosis and treatment in an ambulatory setting [2–4]. In light of the burden HMB places on women, their families, health services and wider society, the availability of ambulatory interventions avoiding the need for hospital admission and prolonged recovery times is an important recent development associated with significant potential health benefits for women [2–4,6].

This article is aimed at showing the current interventional diagnostic and therapeutic procedures which can be safely and effectively accomplished in the ambulatory setting, increasing patients' satisfaction and reducing healthcare costs.

The ambulatory setting & HMB

Traditionally, the management for HMB has been accomplished in the in-patient setting, that is, in hospital operating theaters under general anesthesia, for both diagnostic (i.e., dilatation of the cervix and curettage of the endometrium) and therapeutic purposes (hysteroscopic, laparoscopic or laparotomic surgery) [7,8]. However, advances in pharmacology, health technologies and equipment have resulted in a trend toward minimally invasive techniques for diagnosing and treating HMB in an ambulatory fashion that is, in an ‘outpatient’ or ‘office’ setting without the need for hospital admission, general anesthesia or prolonged recovery [1]. The ambulatory management of HMB includes interventional procedures for diagnosis for example, global and directed endometrial biopsy and medical treatment, for example, levonorgestrel intrauterine system (LNG-IUS; Mirena, Bayer HealthCare, PA, USA) insertion and surgical treatment encompassing a variety of operative hysteroscopic procedures and second-generation endometrial ablation. These interventions are described below.

Diagnostic procedures

Blind endometrial sampling

Blind endometrial biopsy is generally performed with a Pipelle® type instrument, that is, a narrow, hollow plastic cannula within which negative pressure can be applied, which facilitates both abrasion and suction of endometrial tissue. The biopsy is associated with few complications, is performed quickly and generally is well tolerated by the patient. The biopsy instrument samples only 10–25% of the endometrial surface such that there are concerns that pathologies may be missed, especially small, focal or relatively inaccessible lesions, for example within the cornual regions, may be missed with blind sampling [9,10]. Despite these potential limitations, blind endometrial biopsy has a high sensitivity for detecting endometrial hyperplasia and cancer, although recent data indicate that preoperative endometrial biopsy may underestimate the final grade of endometrial cancer. Endometrial biopsy does, however, have a low sensitivity for detecting intracavity focal lesions, including polyps and submucosal fibroids [9,10].

Hysteroscopically targeted biopsies

Hysteroscopically targeted biopsies are more likely to uncover focal pathology than blind endometrial sampling; in one retrospective cohort study of 639 women evaluated by diagnostic office hysteroscopy and endometrial biopsy, more than 50% of intrauterine lesions were missed when a blind endometrial sampling was performed [9,10]. Hysteroscopically directed biopsy of the endometrium requires specially designed, finely engineered forceps, 3–7 Fr in diameter such that they can be passed down the ancillary working channel of a miniature operative continuous flow hysteroscope. Among 5 Fr instruments, the grasping forceps with teeth (‘crocodile’ forceps) are preferred to spoon biopsy ones as they can collect a larger amount of tissue thanks to the double length of the two jaws and the presence of small teeth on both sides of the jaws to keep hold of the material obtained. A variety of such modifications designed to aid tissue retrieval to the tip of the hysteroscopic grasping forceps are available.

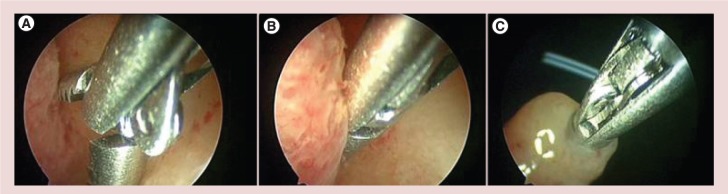

The standard technique of directed biopsy has been a ‘punch’ biopsy, where the hysteroscopic biopsy forceps bite into the endometrium, and are then closed [11]. The mucosa remains inside the jaws and partially around them. The instrument is then extracted through the operative channel while the hysteroscope remains inside the uterine cavity. However, during the process of extracting the instrument, due to the small diameter of the operative channel, the surrounding material is shaved away from around the tip. Thus the final amount of tissue to be sent to the pathologist is strictly related to the internal volume of the two jaws of the forceps, which very often results in an inadequate amount of tissue for histological diagnosis. In order to routinely collect enough endometrium for a correct histological examination, Bettocchi proposed a modified technique; the so-called ‘grasp biopsy’ [11]. Here, the biopsy forceps are positioned with the jaws open, against the endometrium to be biopsied and then pushed into the tissue and along it for around 0.5–1 cm. Once a large portion of mucosa has been removed, the two jaws are closed and the hysteroscope is retired from the uterine cavity, without pulling the tip of the instrument back into the channel (Figure 1). So, not only the sample inside the forceps jaws but also the exceeding tissue protruding outside the jaws can be taken, thus providing the pathologist with a larger amount of tissue.

Figure 1.

Technique of ‘grasp biopsy’. (A) The biopsy forceps are placed against theendometrium to be biopsed with the jaws open and then pushed into the tissue and along it for around 0.5–1 cm. (B) Once a large portion of mucosa has been detached, the two jaws are closed. (C) The whole hysteroscope is removed from the uterine cavity, without pulling the tip of the instrument back into the channel.

When the endometrium is atrophic bipolar electrodes may be used to biopsy an atypical area seen at diagnostic hysteroscopy. The technique consists of drawing with the electrode a sort of square surrounding the target area; the submyometrial tissue is then identified and partially cut, allowing grasping forceps with teeth to remove the atypical area. The relatively recent introduction of hysteroscopic morcellators [12–14] has also facilitated directed biopsy with the potential advantage over traditional grasping forceps of retrieving a greater tissue sample under vision without the need for repeated instrumentation.

Medical intervention

Levonorgestrel IUS insertion

The LNG-IUS is a T shaped intrauterine device releasing a steady amount of levonorgestrel (20 μg/24 h) from a steroid reservoir around the vertical stem of the device. The device releases a high concentration of levonorgestrel locally to the endometrial tissue, which results in an atrophic endometrium owing to decidualization and suppression of the endometrial glands. In addition to its potent local effects, the LNG-IUS promotes low systemic levels of levonorgestrel and does not cause progestin-related adverse effects [15,16]. The LNG-IUS is widely used for treating dysfunctional HMB and has been shown to be widely effective and has led to a reduction in the rate of hysterectomy for this indication. Moreover, the indications for the LNG-IUS are increasing, encompassing both dysfunctional, organic (intramural/subserous fibroid-associated) and adenomyosis-associated HMB [15,16].

The LNG-IUS can be inserted in a routine outpatient clinic, but the ambulatory setting aids easy, less painful placement and is particularly useful where there are potential adverse fitting factors such as obesity, nulliparity, previous cervical surgery, previous Caesarean section and fibroids. A preliminary outpatient hysteroscopy is often useful to exclude focal intrauterine pathologies, assess the dimensions, contour and suitability of the uterine cavity and to aid placement of the LNG-IUS in the ambulatory environment [15,16].

Surgical intervention

Ambulatory operative hysteroscopy

With ongoing developments in the field of hysteroscopy during the last 15 years, hysteroscopic surgery is becoming safer and less invasive for the patient [17,18]. Improved technology has enabled us to perform many operative procedures in an ambulatory or ‘outpatient/office’ setting (Figure 2) without significant patient discomfort and with potentially significant cost savings [17]. The development of smaller diameter hysteroscopes with continuous flow system features and working channels through which operative instruments can be introduced has made it possible to treat some uterine and cervical diseases without the traditional need for cervical dilation or general anesthesia [17,18].

Figure 2.

Surgical ambulatory unit for hysteroscopy at the University ‘Federico II’ of Naples.

Outpatient operative hysteroscopy reduces the distinction between a diagnostic and an operative procedure, shifting the focus in healthcare away from inpatient diagnosis and treatment. Use of specially designed hysteroscopic mechanical instruments (e.g., scissors, biopsy cup, graspers and corkscrews) has long been the only way to perform operative procedures in an outpatient setting. However, although grasping forceps and scissors are excellent for treating adhesions, cervical polyps and endometrial polyps smaller than or the same size as the internal uterine ostium, larger endometrial polyps or thick lesions (e.g., submucous fibroids) were difficult to be treated successfully using such miniature, fragile instruments and without the need for cervical dilation.

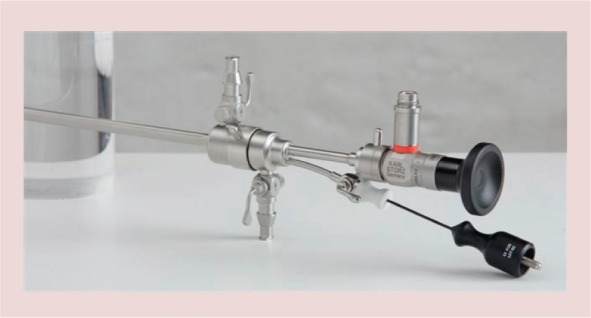

An important technologic advance occurred in 1997 with the introduction of a versatile bipolar electrosurgery system dedicated to hysteroscopy, the Gynecare VersaPoint® (Ethicon, Inc., NJ, USA) (Figure 3), which represents a key point in the history of office operative hysteroscopy [15]. With use of 5 Fr bipolar electrodes, (Figure 4) the number of pathologic conditions treated using office operative hysteroscopy has increased tremendously, reducing the use of the resectoscope and the operating room to a smaller number of cases [17]. More recently a new generation of electrical generators, allowing the use of bipolar energy on miniaturized electrodes, has been presented (Autocon 400 II, Karl Storz Endoscopy, Germany) (Figure 5). The main advantage of these instruments is to be reusable and therefore to reduce the costs of office operative procedures. The application of this electrode and the technique used to perform the procedures is the same of those described for the Versapoint® system [17].

Figure 3.

Versapoint electrosurgical system (Gynecare, Ethicon Inc., NJ, USA). (A) Versapoint I (introduced in 1997); (B) Versapoint II (introduced in 2011).

Figure 4.

The VersaPoint system (Gynecare; Ethicon Inc., NJ, USA) also include three disposable co-axial bipolar electrodes designed to cut, desiccate (coagulate) and vaporize tissue: the Twizzle (on the top), specifically for precise and controlled vaporization (resembling cutting), the Spring (in the middle), used for diffuse tissue vaporization and the Ball, to coagulate tissues. The Twizzle electrode is preferred to the others because it is a more precise ‘cutting’ instrument and it can work closer to the myometrium with a lower power setting and consequently with less patient discomfort.

Figure 5.

Reusable 5 Fr bipolar electrode (Karl Storz, Tuttlingen, Germany) inserted into the operative channel of the Office-Continuous – Flow – Operative Hysteroscopes, “size 5” (Karl Storz, Tuttlingen, Germany).

The feasibility of outpatient uterine surgery is not just dependent upon recent technological advances in instrumentation such as miniaturization of equipment, but also the favorable anatomical characteristics of the uterus itself. The sensitive innervations of the uterus originate in the myometrium and extend to the outer serosal surface whereas the endometrium and any fibrotic tissue within the cavity are not sensitive. Thus, procedures can be carried out without use of analgesia or anesthesia. However, careful operative technique is of paramount importance, in particular avoiding inadvertent deep penetration of the superficial myometrium when resecting lesions such as polyps, maintaining the lowest possible distension pressures and expediting procedures through efficient surgical technique [17].

The feasibility of outpatient operative hysteroscopy has been demonstrated in many, usually uncontrolled, single center observational case series. Initial series reported the feasibility and acceptable pain scores with the use of miniature mechanical instruments to remove cervical and endometrial polyps along with adhesiolysis. One such series reported 4863 mechanical outpatient hysteroscopic procedures. An innovative vaginoscopic approach was adopted, avoiding the use of vaginal or cervical instrumentation, and procedures were performed using a 5.0 mm diameter operative hysteroscope and mechanical 5 Fr instruments [11]. Mechanical procedures have largely been superseded by the use of bipolar electrodes such as the Versapoint® system and more recently hysteroscopic morcellators, with similarly successful reports of feasibility and acceptability for a range of uterine pathologies. The economic benefits of office operative hysteroscopy was first suggested in 2000 from a case series in Canada where cost-savings per case of at least 50% when compared with the inpatient hospital equivalent were estimated. Since then more sophisticated economic models have been used to evaluate cost efficiency [18].

In contrast to feasibility, the clinical effectiveness of outpatient uterine surgery to treat abnormal bleeding including HMB has been less well evaluated. A large, multicenter randomized controlled trial from the UK (the OPT trial) has evaluated clinical outcomes in terms of symptom alleviation in addition to feasibility, acceptability and economic outcomes [19]. The findings from this study will hopefully be able to guide practice especially in the management of HMB and uterine polyps.

Polypectomy

Small endometrial and cervical polyps (<0.5 cm) are generally easy and quick to remove using reusable miniaturized mechanical instruments such as sharp scissors and/or grasping forceps, which should be used in preference to more expensive technologies [11]. The outpatient operative technique for endometrial polyps consists of grasping the polyp base with open jaws, to close them and to gently push toward the uterine fundus. Cervical polyps, however, should be treated with sharp scissors because of their fibrotic base, which precludes the use of grasping forceps, which could leave some well-vascularized tissue at the base of the polyp that can result in regrowth of the polyp [11]. Larger cervical polyps >0.5 cm usually require the Versapoint twizzle or spring electrode to cut their fibrotic base [17].

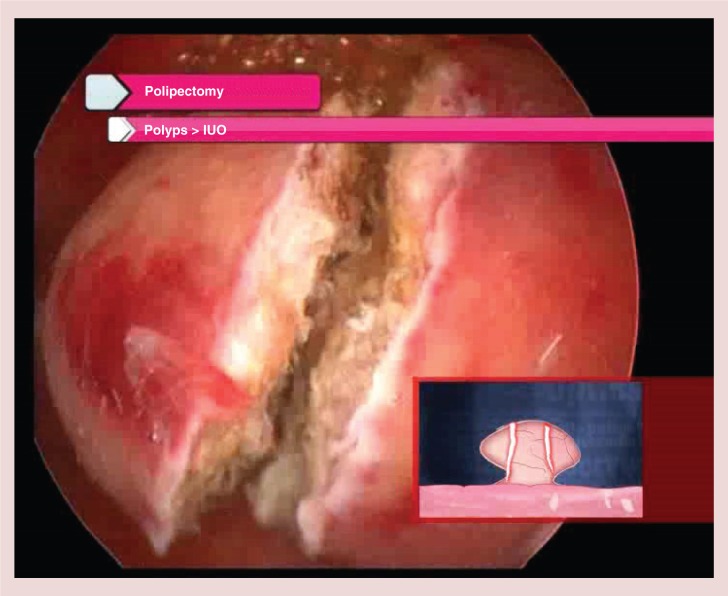

Larger endometrial polyps require different techniques, according to the relation between polyp and internal uterine ostium sizes and the nature of the polyp; fibrous or glandular. If the internal uterine ostium is judged to be wide enough to extract the polyp intact then the base of the polyp might be cut with scissors or better by using a Versapoint twizzle or spring electrode [17]. An alternative approach is to adopt the same mechanical technique used for smaller polyps, repeating it several times up to the detachment of the polyp from its base in the myometrium. Softer, collapsible glandular polyps are generally easier to extract en bloc compared with more fibrous lesions. When the endometrial polyp has a larger size than the internal uterine ostium, then the lesions is unlikely to be removable intact using purely hysteroscopic methods [17]. Blind dilatation of the cervix and instrumentation with larger mechanical instruments may become necessary but this can result in an arduous and lengthy process with low patient's satisfaction and potential for complications. A preferable technique is to slice the polyps with the Versapoint electrode from the free edge to the base into two to three fragments, large enough to be pulled out through the uterine cavity using 5 Fr crocodile forceps (Figure 6) [17].

Figure 6.

Slicing technique for endometrial polyps larger than internal uterine ostium.

IUO: Internal uterine ostium.

In some cases, the Versapoint twizzle electrode can be bent by 25–30°, enough to obtain a ‘hook’ electrode to facilitate removal of the entire base of a endometrial polyp without going too deep in the myometrium, especially fundally located lesions [17]. The bending of the electrode may be obtained by pushing it against the cervix or by the operator's finger and then introducing the hysteroscope in the uterine cavity with the electrode's tip just outside the operating channel. However, such modifications are not recommended by the manufacturer's.

Myomectomy

The outpatient technique is similar to polypectomy and is applied on submucous fibroids <1.5 cm with the difference that, due to their higher tissue density, the lesions are first divided into two half-spheres and then each of these is sliced as described for polyps. Particular attention has to be paid in case of partially intramural fibroids [17]. To avoid any myometrial stimulation or damage of the surrounding healthy myometrium, the fibroid is first gently separated from the pseudocapsule using mechanical instruments such as grasping forceps or scissors or using a nonactivated bipolar electrode. Once the intramural section becomes intracavitary, the fibroid is then sliced with the bipolar electrode [17].

Grade 1 and 2 submucous fibroids with prevalent intramural portion are generally not treatable in the outpatient based setting because removal would necessitate painful incision into the deeper myometrium. Furthermore, the use of miniature equipment is unlikely to allow adequate distension and visualization especially if there is bleeding from the fibroid bed so that judging the depth of myometrial penetration will be imprecise. However, we have developed a technique to prepare such fibroids in the outpatient setting for subsequent resectoscopic procedure under general anesthesia. The Office Preparation of Partially Intramural Myomas (OPPIUM) technique involves incising the endometrial mucosa which covers the fibroid by means of scissors or 5 Fr bipolar electrodes [20]. The incision is made along the reflection line on the uterine wall, up to the precise identification of the cleavage surface between the fibroid and pseudocapsula, thus facilitating the protrusion of the intramural portion of fibroid into the cavity during subsequent menstrual cycles (Figure 7). This action may in turn facilitate the subsequent total removal of the lesion via resectoscopy, as the surgeon will deal with a lesion which is predominantly intracavity that is, a grade 0 or 1 submucous fibroid [20].

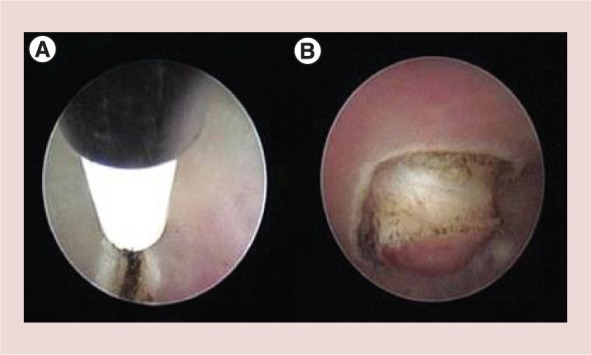

Figure 7.

OPPIuM technique. (A) Incision of endometrial mucosa, which covers the fibroid by means of 5 Fr bipolar electrode. (B) Identification of the cleavage surface between the fibroid and pseudo capsule.

Repositioning of misplaced LNG-IUS

Routinely, the insertion of the LNG-IUS does not require hysteroscopy. However, in some cases in which this treatment has apparently failed, it may useful to perform an outpatient hysteroscopy to check the positioning of the device. On occasion the device may be found misplaced in the isthmic area as a result of incorrect positioning or partial expulsion. In such instances, the same LNG-IUS can be repositioned by grasping it with forceps or simply by pushing the device's distal extremity with the tip of the hysteroscope.

Treatment of vaginal lesions

Some vaginal pathologies traditionally approached in the operating room under general anesthesia may be treated in the outpatient-based setting. Vaginal polyps can be easily diagnosed through the vaginoscopic approach and removed in the same setting by means of miniaturized bipolar electrodes. Closing vulvar labia may help to maintain an adequate intravaginal distension [21].

Second-generation endometrial ablation

During the past decade, the diffusion of endometrial ablation technology has modified the treatment of dysfunctional HMB. Such new treatment options have fewer risks than traditional resectoscopic procedures, are quicker and require shorter recovery times [22–24]. As technology has advanced, with proper patient selection, equipment and anesthesia techniques, endometrial ablation can be performed safely and effectively also in the outpatient setting. However, whilst the ablative procedures are generally short and easily performed in the vast majority of women, the procedure can be associated with significant pain. Thus, patient preferences should be taken into account along with medical co-morbidities [22–24].

Protocols vary but generally involve the use of pre and postoperative analgesia and intraoperative local anesthesia [22]. Conscious sedation is employed in some centers although evidence to support such practices is lacking at present. Moreover, by using sedation the complexity of the procedure is enhanced which can have repercussions on resources and capabilities in the outpatient setting. For example, in the USA, more than 20 states differentiate procedures as level I surgery and level II surgery depending largely on the types of anesthesia used [22]. There are specific requirements for both equipment and procedure room and for staff certification when a procedure is classified as level II as opposed to level I. Level I surgery is defined as minor procedures in which preoperative medication and/or local anesthesia is used, with no drug-induced alteration of consciousness other than minimal anxiolysis of the patient [23,25]. Level II office surgery includes procedures that require the administration of minimal or moderate intravenous, intramuscular or rectal sedation/analgesia, thus making postoperative monitoring necessary.

There are currently five second-generation global endometrial ablation devices available in USA, all of which lead to a high degree of patient satisfaction. The results of most studies, including the original US FDA pivotal trials, show the clinical outcomes for all of the devices to be similar, with diary score success rates ranging from 73.3 to 87% and patient satisfaction rates of 86 to 99% [26–33]. The Gynecare Thermachouce® and the Hologic's NovaSure® System are the ablative systems currently in most widespread use [23,25,34–35].

Conclusion

The ‘ambulatory’ or ‘outpatient’ setting is increasingly being used to both diagnose and treat HMB. Pelvic ultrasound, hysteroscopy, blind and directed endometrial biopsy facilitate diagnosis and in many cases immediate treatment, such as the fitting of the LNG-IUS or polypectomy can be undertaken; the so called ‘see & treat’ approach. In addition to hysteroscopic intervention for removing polyps and fibroids that may be associated with HMB, global endometrial ablation can be successfully and safely performed. Future research is required to evaluate new technologies and treatments for HMB in the ambulatory setting, comparing these approaches with the conventional inpatient, general anesthetic setting where necessary, in terms of feasibility, acceptability, effectiveness and cost–effectiveness. Local protocols should be developed and best practice shared through the formulation of evidence-based guidelines.

Future perspective

What about the future? From a speculative view point in the future we could use endoscopes providing 3D view or another possibility is to realize video endoscopes for hysteroscopy thanks to ‘chip on tip’ technology. Furthermore, technical and technological development may further increase the number of uterine, cervical and vaginal conditions suitable to an office-based treatment. All these innovative technologies would support the ‘see and treat’ approach to be proposed as the gold standard for the investigation and treatment of HMB.

Executive summary

Thanks to the advancements of technology and technique, the diagnosis and treatment of heavy menstrual bleeding is increasingly being performed in the ‘ambulatory’ or ‘outpatient’ setting, through the so called ‘see and treat’ approach.

Particularly, hysteroscopy allows diagnosis and in many cases immediate treatment of most of intrauterine pathologies.

In addition to hysteroscopic intervention, the fitting of the levonorgestrel intrauterinesystem, or global endometrial ablation can be successfully and safely performed.

Financial & competing interests disclosure

The authors have no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Jones GL, Kennedy SH, Jenkinson C. Health-related quality of life measurement in women with common benign gynecologic conditions: a systematic review. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 187, 501–511 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Menorrhagia (heavy menstrual bleeding); CNN.com. www.cdc.gov

- 3.Menorrhagia (heavy menstrual bleeding). MayoClinic Health Library. www.riversideonline.com

- 4.PreventDisease. Menstruation: heavy bleeding (menorrhagia). http://preventdisease.com/diseases/diseases.shtml

- 5.Munro MG, Critchley HO, Broder MS, Fraser IS; FIGO Working Group on Menstrual Disorder. FIGO classification system (PALM-COEIN) for causes of abnormal uterine bleeding in nongravid women of reproductive age. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 113(1), 3–13 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Women with inherited bleeding disorders: surgical options for menorrhagia. Canadian Hemophilia Society; www.hemophilia.ca/en [Google Scholar]

- 7.Apgar BS, Kaufman AH, George-Nwogu U, Kittendorf A. Treatment of menorrhagia. Am. Fam. Phys. 75, 1813–1819 (2007). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fast Facts for Your Health: Menorrhagia. National Women's Health Resource Center (NWHRC), Washington, DC, USA: www.healthywomen.org. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bettocchi S, Ceci O, Vicino M, et al. Diagnostic approach of dilation and curettage. Fertil. Steril. 75, 803–805 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Svirsky R, Smorgick N, Rozowski U, et al. Can we rely on blind endometrial biopsy for detection of focal intrauterine pathology? Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 199(2), 115.e1–3 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bettocchi S, Ceci O, Nappi L, et al. Operative office hysteroscopy without anesthesia: analysis of 4863 cases performed with mechanical instruments. J. Am. Assoc. Gynecol. Laparosc. 11(1), 59–61 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clinical trials database: NCT01509313. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01509313

- 13.Franchini M, Zolfanelli F, Gallorini M, et al. Hysteroscopic polypectomy in an office setting: specimen quality assessment for histopathological evaluation. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 189, 64–67 (2015) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garbin O, Schwartz L. New in hysteroscopy: hysteroscopic morcellators. Gynecol. Obstet. Fertil. 42(12), 872–876 (2014) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hurskainen R, Teperi J, Rissanen P, et al. Quality of life and cost-effectiveness of levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system versus hysterectomy, for treatment of menorrhagia: a randomized trial. Lancet 357, 273–277 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hurskainen R, Teperi J, Rissanen P, et al. Clinical outcomes and costs with the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system or hysterectomy for treatment of menorrhagia: randomized trial 5-year follow-up. JAMA 291, 1456–1463 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bettocchi S, Ceci O, Di Venere R, et al. Advanced operative office hysteroscopy without anaesthesia: analysis of 501 cases treated with a 5 Fr bipolar electrode. Hum. Reprod. 17, 2435–2438 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saridogan E, Tilden D, Sykes D, Davis N, Subramanian D. Cost-analysis comparison of outpatient see-and-treat hysteroscopy service with other hysteroscopy service models. JMIG 17, 518–525 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Middleton L, Diwakar L, Smith P, et al. Outpatient versus inpatient uterine polyp treatment for abnormal uterine bleeding: randomised controlled non-inferiority study. BMJ 350, h1398 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bettocchi S, Di Spiezio Sardo A, et al. A new hysteroscopic technique for the preparation of partially intramural myomas in office setting (OPPIuM technique): a pilot study. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 16(6), 748–54 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Di Spiezio Sardo A, Bettocchi S, Spinelli M, et al. Review of new office-based hysteroscopic procedures 2003–2009. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 17(4), 436–48 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baskett TF, Clough H, Scott TA. NovaSure bipolar radiofrequency endometrial ablation: report of 200 cases. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Can. 27, 473–476 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cooper J, Gimpelson R, Laberge P, et al. A randomized, multicenter trial of safety and efficacy of the NovaSure system in the treatment of menorrhagia. J. Am. Assoc. Gynecol. Laparosc. 9, 418–428 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fertility Answers. Heavy Bleeding and Endometrial Ablation. www.fertilityanswers.com

- 25.Gallinat A. An impedance-controlled system for endometrial ablation: five-year follow-up of 107 patients. J. Reprod. Med. 52, 467–472 (2007). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kleijn JH, Engels R, Bourdrez P, Mol BW, Bongers MY. Five-year follow up of a randomised controlled trial comparing NovaSure and ThermaChoice endometrial ablation. BJOG 115, 193–198 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Laberge PY, Sabbah R, Fortin C, Gallinat A. Assessment and comparison of intraoperative and postoperative pain associated with NovaSure and ThermaChoice endometrial ablation systems. J. Am. Assoc. Gynecol. Laparosc. 10, 223–232 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lethaby A, Penninx J, Hickey M, Garry R, Marjoribanks J. Endometrial resection/ablation techniques for heavy menstrual bleeding. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. (8), CD001501 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Loffer FD, Grainger D. Five-year follow-up of patients participating in a randomized trial of uterine balloon therapy versus rollerball ablation for treatment of menorrhagia. J. Am. Assoc. Gynecol. Laparosc. 9, 429–435 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marsh F, Thewley J, Duffy S. Randomized controlled trial comparing ThermaChoice III in the outpatient versus daycase setting. Fertil Steril. 87, 642–650 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.NovaSure Endometrial Ablation in Your Office. Marketing brochure 87178–001 Rev A. Cytyc Corp., Marlborough, MA, USA: (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sabbah R, Desaulniers G. Use of the NovaSure impedance controlled endometrial ablation system in patients with intracavitary disease: 12-month follow-up results of a prospective, single-arm clinical study. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 13, 467–471(2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Samuel N, Malick S, Middleton L, Daniels J, Gupta J, Clark J. The COAT Trial: a randomised controlled trial comparing outpatient endometrial ablation techniques (Novasure™ vs Thermachoice™): menstrual bleeding and quality of life outcome. Gynaecol. Surgery 5(Suppl. 1), FC-97 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Deb S, Flora K, Atiomo W. A survey of preferences and practices of endometrial ablation/resection for menorrhagia in the United Kingdom. Fertil. Steril. 90, 1812–1817 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.El-Nashar SA, Hopkins MR, Creedon DJ, et al. Prediction of treatment outcomes after global endometrial ablation. Obstet. Gynecol. 113, 97–106 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]