Abstract

The protein kinase p38α mediates cellular responses to environmental and endogenous cues that direct tissue homeostasis and immune responses. Studies of mice lacking p38α in several different cell types have demonstrated that p38α signaling is essential to maintaining the proliferation-differentiation balance in developing and steady-state tissues. The mechanisms underlying these roles involve cell-autonomous control of signaling and gene expression by p38α. Here we show that p38α regulates gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT) formation in a non-cell-autonomous manner. From an investigation of mice with intestinal epithelial cell-specific deletion of the p38α gene, we find that p38α serves to limit NF-κB signaling and thereby attenuate GALT-promoting chemokine expression in the intestinal epithelium. Loss of this regulation results in GALT hyperplasia and, in some animals, mucosa-associated B cell lymphoma. These anomalies occur independently of luminal microbial stimuli and are likely driven by direct epithelial-lymphoid interactions. Our study illustrates a novel p38α-dependent mechanism preventing excessive generation of epithelial-derived signals that drive lymphoid tissue overgrowth and malignancy.

Introduction

The kinase p38 serves signaling functions that are conserved in a wide range of eukaryotic species—from single-celled fungi to mammals (1). In all organisms possessing its homologues, p38 is activated by various forms of environmental stress, and signals to deploy appropriate cellular coping mechanisms. Besides its role in the cell-autonomous stress response, p38 functions downstream of receptors for cell-extrinsic signals that direct coordinated cell activities in multicellular organisms. Conversely, p38 also functions upstream of such receptors by modulating the production of their ligands. Receptor-mediated cell-to-cell communication that entails p38 signaling as an intracellular module is a theme prominent in the context of the immune response as well as tissue development and homeostasis. Among the four mammalian p38 isoforms, p38α is the most widely expressed in tissues and has established connections with diverse signaling receptors for microbial products, cytokines, growth factors, and hormones (2). By examining the effects of p38α gene ablation in mice, several studies including ours have revealed a role for p38α in tissue homeostasis, inflammation, and tumorigenesis (3). In parenchymal cells of various tissues, p38α signaling limits proliferation while promoting differentiation and survival (4-9). Hence, loss of p38α signaling in hepatocytes, keratinocytes, and intestinal epithelial cells (IECs) leaves them prone to damage and neoplastic transformation upon exposure to chemical irritants or carcinogens. It remains unclear, however, whether p38α signaling in parenchymal cells also performs non-cell-autonomous functions, influencing the formation and maintenance of the stromal and hematopoietic-derived compartments of the tissue.

The intestinal mucosa provides vital physiological functions such as permeability barrier, nutrient transport, and neuroendocrine control. This versatility is mainly attributable to the functional capabilities and genetic program intrinsic to the mucosal epithelial compartment. IECs are also pivotal to orchestrating immune defense against pathogens and establishing tolerance to innocuous commensal microbes and dietary proteins. Lymphocytes and other hematopoietic-derived cells, highly abundant in intestinal tissues, also contribute to immunity and tolerance by furnishing effector and regulatory mechanisms that complement those conferred by IECs. While T cells and plasma cells are found diffusely in the lamina propria, the vast majority of intestinal B cells are located within follicular structures. Several distinct types of lymphoid structures—collectively termed gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT)—are present in mammalian intestines (10, 11). Some of these structures develop prenatally under genetically programmed guidance, as exemplified by Peyer's patches in the ileum and the mesenteric lymph nodes. RORγt-expressing lymphoid tissue inducer (LTi) cells are essential to this developmental process. Other forms of GALT, such as isolated lymphoid follicles (ILFs), develop postnatally. ILFs are discrete B cell aggregates scattered across the small intestine and the colon, and contain T cells and other hematopoietic-derived cell types as minor constituents. ILF development is not only genetically programmed but also conditioned by environmental inputs such as luminal microbial stimulation, and proceeds in two phases: the formation of RORγt+ LTi-like cell clusters known as cryptopatches, and subsequent recruitment of B cells to cryptopatches for follicle growth. The GALT thus formed participates in local immune defense as well as shaping the systemic B cell repertoire. GALT-mediated immunity is phylogenetically more recent relative to epithelial-intrinsic defense mechanisms, and likely evolved concomitantly with epithelial-derived signals that direct GALT development.

In this study, we discover a novel mechanism that mediates epithelial-lymphoid interactions in the intestinal mucosa: p38α functions to attenuate NF-κB target gene expression in IECs and thereby limits epithelial-derived signals driving GALT formation and malignancy. Our findings illustrate a critical role for the intestinal epithelium in GALT homeostasis, and point to p38α signaling as a key regulatory module in this process.

Materials and Methods

Animals

The mouse lines p38αΔIEC (Mapk14fl/fl-VilCre) and IEC-IKKβEE (transgenic Vil-IKKβEE) were previously described (8, 12). RAG1-knockout mice (Rag1tm1Mom) were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory. All mice were on a C57BL/6 background and maintained in a specific-pathogen-free condition. To suppress establishment of the intestinal microbiota, mice were administered a mixture of the following antibiotics in drinking water: ampicillin (1g/L), neomycin sulfate (1 g/L), vancomycin (0.5 g/L), and metronidazole (1g/L; all from Sigma). Treatment with antibiotics began in utero by providing antibiotics to the mothers as soon as the mating cages were set up, and continued postnatally until the mice were sacrificed for analysis. To induce colitis, mice were administered 2.5% or 3.5% dextran sulfate sodium (DSS) in drinking water for seven days; afterwards, drinking water without DSS was provided. Survival was monitored daily over a period of fourteen days. All animal experiments were conducted under Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee-approved protocols.

Cell lines and cell culture

MODE-K mouse intestinal epithelial cells (13) were cultured in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium with high glucose (Gibco) supplemented with fetal bovine serum (10%), penicillin (50 unit/ml), and streptomycin (50 μg/ml). To enrich cells expressing the puromycin resistance gene, puromycin (2 μg/ml; EMD Millipore) was added to culture medium 36 h after plasmid DNA transfection. Cells were analyzed after 48 h of puromycin selection.

Reagents

Cultured cells were treated with mouse recombinant tumor necrosis factor (TNF; a gift from C. Libert, Ghent University), and the TAK1 inhibitor (5Z)-7-oxozeaenol (Sigma). The RNAi Consortium plasmids expressing p38α-specific shRNA (Dharmacon; Supplemental Table 1) were in the pLKO.1 vector. RelA- and p38α-specific siRNA was from the Stealth RNAi collection (Life Technologies; Supplemental Table 1). Cell transfection with plasmid DNA and siRNA was performed using FuGENE HD (Roche) and Lipofectamine RNAiMAX (Life Technologies) transfection reagents, respectively. Flow cytometry was performed using fluorescent dye-conjugated antibodies against the following markers: B220 (RA3-6B2) and CD3e (145-2C11; both from eBioscience). Immunostaining of tissue sections and bone marrow smears was performed with antibodies against the following markers: B220 (RA3-6B2), CD4 (RM4-5), CD11c (HL3; all from BD Biosciences); CD3e (SP7; Abcam); RORγt (B2D; eBioscience); and RelA (sc-372; Santa Cruz Biotechnology). For detection of germinal centers, tissue sections were stained with biotin-conjugated peanut agglutinin (PNA; Sigma). Immunoblotting was performed using antibodies against the following proteins: RelA (sc-372), p38α (sc-535), AKT1/2/3 (sc-8312), BRG1 (sc-10768; all from Santa Cruz Biotechnology); p38β (33-8700; Life Technologies); p38γ and p38δ (gifts from Simon Arthur, University of Dundee).

Lymphocyte isolation and flow cytometry

Lymphocytes were isolated from mouse colons and Payer's patches as described (14). Single-cell suspensions thus prepared were incubated with Fc receptor-blocking anti-CD16/CD32, stained with fluorescent-conjugated antibodies, and analyzed by flow cytometry using FACSCanto (BD Biosciences) and FlowJo software (Tree Star).

Histology and immunofluorescence

Mouse ileum and colon samples were frozen in OCT medium or formalin-fixed and embedded in paraffin. Sections of 5-7 μm in thickness on slides were stained with hematoxylin and eosin or incubated with marker-specific primary antibodies. Bone marrow smears on slides were air-dried, fixed in methanol, and stained with Wright-Giemsa dyes (Sigma) or incubated with marker-specific antibodies. For fluorescence labeling, the tissue sections and smears were incubated with secondary antibodies conjugated with Alexa Fluor 488 or Alexa Fluor 594 or with streptavidin conjugated with Alexa Fluor 594 (Molecular Probes) and counterstained with Hoechst 33342 (Molecular Probes). Immunostained samples were analyzed by fluorescence microscopy.

Analysis of fecal bacteria

Fecal pellets were collected from mice, disintegrated and serially diluted in phosphate-buffered saline, and plated on Luria-Bertani agar plates. Colonies were counted after 16 h of incubation at 37°C.

Analysis of immunoglubulin gene rearrangement

DNA from lymphomas and splenic B cells was analyzed by PCR using degenerate primers specific to different products of VH-DJH rearrangement (15).

Protein and RNA analysis

Whole-cell lysates and extracts of cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions were prepared and analyzed by immunoblotting as described (16, 17). Real-time quantitative PCR was performed using gene-specific primers (Supplemental Table 2).

Results

IEC-specific ablation of p38α expression results in colonic lymphoid hyperplasia

We previously generated and characterized mice with IEC-restricted p38α deficiency (designated p38αΔIEC). Their intestinal epithelium exhibited an imbalance in steady-state proliferation and differentiation: a dramatic increase in the former at the expense of the latter, which lead to elongated epithelial lining of the villus and the crypt (8). It had remained unexplored, however, whether p38α signaling in IECs also serves non-cell-autonomous functions, for example, related to the organization and maintenance of the non-epithelial compartments of the intestinal mucosa. Intriguingly, we found large increases in the absolute number of B cells and T cells in p38αΔIEC relative to WT colons (Fig. 1A). We performed histological analysis of colon tissue sections to determine whether these changes reflected increased numbers of diffuse lamina propria lymphocytes or increased cellularity in the follicular aggregates. Abnormal enlargement of ILFs was evident in p38αΔIEC colons at 12 weeks of age (Fig. 1, B and C). It is notable that although the number of ILFs in the colon (i.e. colonic ILF density) increased in some p38αΔIEC mice, the overall difference between the WT and p38αΔIEC groups did not reach significance (Fig. 1D). The difference in ILF size, however, remained significant throughout life, with nearly all of p38αΔIEC mice exhibiting oversized ILFs (greater than 300 μm in diameter) independently of their ILF numbers (Fig. 1D). Colonic ILF hyperplasia of this magnitude rarely developed among WT mice. Therefore, p38α signaling in IECs appeared to regulate the growth of committed ILFs but not as critically the commitment of their formation per se. PNA staining showed that many but not all of overgrown ILFs in p38αΔIEC colons (four out of eight examined) had germinal centers, whereas there were few ILFs with germinal centers in WT colons (Fig. 1E).

Figure 1. Mice lacking p38α in intestinal epithelial cells develop colonic lymphoid hyperplasia.

Colon tissues were obtained from WT and p38αΔIEC mice at 12 to 16 weeks of age.

(A) The number of colonic B220+ and CD3+ cells was determined by flow cytometry, and is shown as mean±SEM (n=3).

(B, C) Colon tissue sections were analyzed by H&E staining (B), and immunostaining for B220 together with counter-staining of DNA (C). Red arrowheads indicate ILFs. Scale bar, 500 μm (B; and C).

(D) The number of colonic ILFs (upper panel) and the proportions of their subsets grouped according to size (lower panel) were determined. **p<0.005.

(E-G) Colon tissue sections were analyzed by PNA staining and immunostaining for B220 (E), and immunostaining for RORγt and B220 (F), and CD11c (G) together with counter-staining of DNA. White arrowheads indicate germinal centers (GC) and the crypt base (CB). Scale bar, 100 μm.

In p38αΔIEC mice, RORγt+ LTi/LTi-like cells and CD11c+ dendritic cells were mainly distributed in areas overlaying the lymphoid follicle and proximal to the follicle-associated epithelium (Fig. 1, F and G). This localization was normal, and suggested that the hyperplastic ILFs developing in p38αΔIEC colons retained the typical architecture of murine ILFs reported in earlier studies (18, 19).

We observed mild hyperplasia of Payer's patches in some p38αΔIEC mice (Supplemental Fig. 1, A-C), yet these cases were episodic in nature and involved only minor changes in extent relative to the marked ILF hyperplasia seen in p38αΔIEC colons. Moreover, ILF hyperplasia was not detected in p38αΔIEC small intestines (Supplemental Fig. 1D). We therefore focused on colonic epithelial-lymphoid interactions for the remaining analysis of this study.

Colonic lymphoid hyperplasia resulting from IEC-specific p38α deficiency occurs independently of microbial stimuli

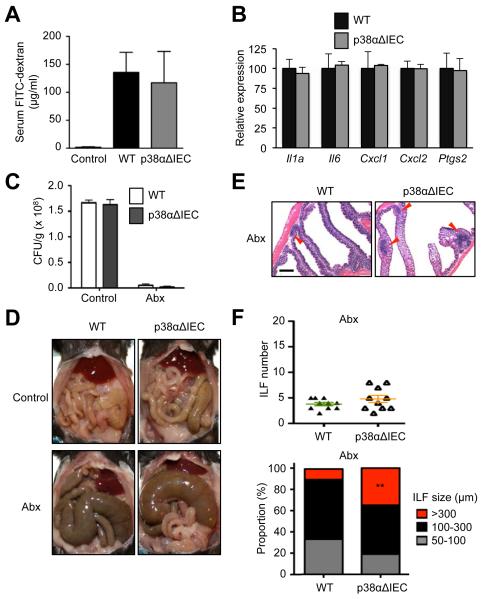

Loss of p38α in the intestinal epithelium might disrupt its barrier function and permit translocation of luminal bacteria and their products across the epithelial layer, a condition that could lead to immune activation and GALT hyperplasia. We investigated whether p38αΔIEC mice manifested evidence supporting this possibility, and first sought to assess their intestinal epithelial permeability. To this end, we traced fluorescently labeled dextran detected in the blood after its oral administration to WT and p38αΔIEC mice. The amounts of circulating dextran in the two groups were comparable (Fig. 2A), suggesting no difference in their barrier integrity. In addition, steady-state colons of p38αΔIEC mice did not exhibit elevated expression of tissue inflammation markers such as Il1a, Il6, Cxcl1, Cxcl2, and Ptgs2 (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2. Epithelial p38α deficiency leads to colonic lymphoid hyperplasia independently of the influence of gut microbiota.

(A) The concentration of FITC-dextran in serum of WT and p38αΔIEC mice was determined after its oral administration, and is shown as mean±SEM (n=3-4).

(B) The expression of the indicated genes in the intestinal epithelium of WT and p38αΔIEC mice was analyzed by qPCR. Data are shown as mean±SEM.

(C-F) WT and p38αΔIEC mice were subjected to long-term antibiotic treatment (Abx) and analyzed together with antibiotic-naïve counterparts (Control). Fecal bacterial counts were determined (C). The abdominal viscera were photographed (D). Colon tissue sections were analyzed by H&E staining (E). Red arrowheads indicate ILFs. Scale bar, 500 μm. The number of colonic ILFs (F, upper panel) and the proportions of their subsets grouped according to size (F, lower panel) were determined. **p<0.005.

We next examined whether the occurrence of ILF hyperplasia in p38αΔIEC mice could be prevented or mitigated by depletion of the intestinal microbiota, which was indeed the case in some but not all gene knockout mouse lines developing similar GALT hyperplasia (20-22). Long-term treatment with broad-spectrum antibiotics effectively depleted intestinal bacteria in WT and p38αΔIEC mice, as indicated by the fecal bacterial counts (Fig. 2C). The animals also displayed cecal enlargement (Fig. 2D), which is characteristic of germ-free and antibiotic-treated animals (23). Microbiota-depleted p38αΔIEC mice developed enlarged ILFs as did antibiotic-naïve p38αΔIEC mice (Fig. 2E). Although antibiotic treatment resulted in crypt hypotrophy in both WT and p38αΔIEC mice, the difference in ILF size persisted between the two groups of microbiota-depleted mice (Fig. 2, E and F). These findings suggested that the development of colonic lymphoid hyperplasia in p38αΔIEC mice was independent of microbial stimuli and driven by more direct epithelial-lymphoid interactions. An IEC-derived signal might, for instance, promote the recruitment or proliferation of lymphocytes comprising the ILF; such a signal might be excessively generated in p38α-deficient IECs.

IEC-specific ablation of p38α expression enhances colitis-associated lymphoid hyperplasia

Apart from steady-state GALT development, lymphoid neogenesis can occur in inflamed intestinal mucosa. Mild colitis induced by oral administration of low-dose (2.5%) DSS led to the growth of ILF-like structures in WT colons but to a greater extent in p38αΔIEC colons (Fig. 3A). We reported that p38αΔIEC mice suffered severe IEC damage after, and eventually succumbed to, high-dose (3.5%) DSS administration (8). GALT hyperplasia in some mutant mouse lines has been associated with an increased severity of experimentally induced colitis (24, 25). The expanded lymphoid compartment in p38αΔIEC mice, however, seemed to contribute little to their susceptibility to DSS-induced colitis; p38αΔIEC mice in a RAG1-deficient background, hence devoid of GALT, showed mortality comparable to those of RAG1-sufficient counterparts upon high-dose DSS treatment (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3. Colitis-associated lymphoid hyperplasia occurs to a greater extent in mice lacking p38α in intestinal epithelial cells.

The indicated mice were administered DSS in drinking water at the indicated concentrations for seven days.

(A) Colon tissues were prepared on d 7 and analyzed by H&E staining. Red arrowheads indicate ILFs. Scale bar, 500 μm.

(B) Survival was monitored daily (n=10).

IEC-specific ablation of p38α expression results in GALT malignancy

In an attempt to identify the long-term sequelae of deregulated GALT development in p38αΔIEC mice, we established groups of mice aged to 48 to 72 weeks. Macroscopically discernible nodules of overgrown ILFs and Peyer's patches emerged in these p38αΔIEC mice (Supplemental Fig. 2A). Furthermore, several aged p38αΔIEC mice had mesenteric lymph node hypertrophy and ectopic lymphoid neogenesis in periportal areas of the liver (Supplemental Fig. 2, A-C), possibly indicating a propagation of GALT hyperplasia and aberrant homing of GALT-derived lymphocytes via the lymphatic and portal venous routes (26). GALT hypertrophy and hepatic lymphoid neogenesis were not observed in similarly aged WT mice.

Remarkably, lymphoid hyperplasia at intestinal and hepatic sites progressed to B cell lymphoma in some p38αΔIEC mice (Supplemental Fig. 2, C and D). Malignant B cells disseminated to the bone marrow in these animals (Supplemental Fig. 2E). Analysis of the immunoglobulin heavy chain gene rearrangement revealed monoclonality of lymphoma from each host, indicating that malignancies in p38αΔIEC mice arose from clonal expansion of transformed B cells (Supplemental Fig. 2F). Taken together, our findings with p38αΔIEC mice suggested that the intestinal epithelium provided critical signals for GALT development and homeostasis, dysregulation of which could lead to lymphoid hyperplasia and malignancy in the intestines and the liver. The generation of such signals seemed to be controlled by epithelial p38α signaling. We sought to identify this p38α-dependent regulatory mechanism operating in IECs.

NF-κB activation in IECs is restrained by p38α

We previously showed that genetic ablation or pharmacological inhibition of p38α resulted in enhanced phosphorylation and activation of TAK1 in various cell types (8). Given that TAK1 is required for NF-κB activation in a multitude of signaling contexts (27, 28), it seemed plausible that loss of p38α could augment NF-κB signaling in IECs. To explore this idea, we first examined the effect of shRNA-mediated p38α gene knockdown (KD) on NF-κB activation, which is associated with the nuclear translocation of NF-κB RelA, in the immortalized mouse IEC line MODE-K. Of the six tested shRNA constructs with different target sequences, two (#2 and #3) were effective at ablating p38α gene expression (Fig. 4A). MODE-K cells expressing shRNA from these constructs showed prolonged nuclear persistence of RelA upon TNF stimulation (Fig. 4B), an effect not observed with control constructs that either lacked an shRNA-encoding sequence (V) or expressed minimally effective shRNA (#5).

Figure 4. Intestinal epithelial cells lacking p38α exhibit NF-κB hyperactivation.

(A) Whole cell lysates were prepared from MODE-K cells expressing shRNA specific to p38α mRNA and control shRNA (V), and analyzed by immunoblotting. Numbers (#1-#6) denote shRNA clones with different target sequences.

(B) Cytoplasmic (Cyto) and nuclear (Nuc) extracts were prepared from control (V and #5) and p38α-KD (#2 and #3) MODE-K cells at the indicated time points after treatment with TNF (50 ng/ml), and analyzed by immunoblotting.

(C, D) Whole cell lysates were prepared from control (V) and p38α-KD (#2) MODE-K cells at the indicated time points after treatment with TNF (50 ng/ml), and analyzed by immunoblotting (C). The amount of phosphorylated (p-) TAK1 relative to that of total TAK1 was determined by densitometry (D).

(E) Cytoplasmic and nuclear extracts were prepared and analyzed as in B. Where indicated, the cells were preincubated with the TAK1 inhibitor 5Z-7-Oz (2 μM) for 1 h before TNF exposure.

(F) Colon tissues were prepared from WT and p38αΔIEC mice orally administered low-dose DSS (2.5%) as in Supplemental Fig. 2 and analyzed by immunostaining for RelA with counter-staining of DNA. Scale bar, 100 μm. Arrowheads indicate nuclei with strong RelA signals.

Consistent with the reported role of p38α in TAK1 regulation, KD of p38α led to increases in basal as well as TNF-induced TAK1 phosphorylation in MODE-K cells (Fig. 4, C and D). NF-κB induction in both control- and p38α-KD cells was sensitive to the TAK1 inhibitor (5Z)-7-oxozeaenol (Fig. 4E). Of note, the rise of basal TAK1 activity in p38α-KD cells prior to TNF stimulation was not sufficient to activate NF-κB, suggesting that TAK1 hyperactivity in p38α-deficient cells is a prerequisite for enhanced NF-κB activation, yet should be accompanied by additional signaling events to effect it.

We next examined by immunofluoresence analysis the subcellular distribution of RelA in the colon tissue of WT and p38αΔIEC mice subjected to low-dose DSS (2.5%) administration (Fig. 4F). RelA signals were diffuse and mainly cytoplasmic throughout WT epithelium. By contrast, clusters of epithelial cells with intense signals of RelA concentrated in the nucleus were detected in p38αΔIEC colons. Therefore, our observations indicated that p38α served to restrain NF-κB activation in both cultured IECs and mouse colonic epithelium.

Enhanced NF-κB signaling in IECs results in GALT hyperplasia

Epithelial NF-κB signaling has been shown to play a key role in intestinal immune homeostasis and defense (29). In particular, NF-κB target gene expression in IECs has been found crucial for hematopoietic-derived cell recruitment to the lamina propria (12, 30). We therefore suspected that enhanced epithelial NF-κB signaling might be causally associated with increased GALT cellularity in p38αΔIEC mice. To address this possibility, we investigated mice expressing a constitutively active form of IKKβ (IKKβEE) in IECs and hence having IEC-restricted NF-κB hyperactivity (12). These mice (designated IEC-IKKβEE) displayed GALT hyperplasia similarly to p38αΔIEC mice (Fig. 5, A and B). ILF numbers in IEC-IKKβEE colons increased moderately but not significantly compared with those in WT colon (Fig. 5C). IEC-IKKβEE mice, however, developed oversized colonic ILFs at a greatly increased rate as well as exhibiting an upward shift in the overall distribution of ILF sizes (Fig. 5C). GALT hyperplasia seen in p38αΔIEC mice and recapitulated in IEC-IKKβEE mice is therefore most likely attributable to enhanced NF-κB signaling in IECs. Unprovoked IEC-IKKβEE mice did not manifest an increased inflammatory tone in the intestinal mucosa; the expression of Il1a, Il6, Cxcl1, Cxcl2, and Ptgs2 was comparable in steady-state intestines of WT and IEC-IKKβEE mice (Fig. 5D). Hence, the overgrowth of ILFs in IEC-IKKβEE mice did not seem secondary to inflammatory responses.

Figure 5. Mice with constitutive NF-κB activation in intestinal epithelial cells develop colonic lymphoid hyperplasia.

Colon tissues were obtained from WT and IEC-IKKβEE mice at 35 to 45 weeks of age.

(A, B) Colon tissue sections were analyzed by H&E staining (A), and immunostaining for B220 together with counter-staining of DNA (B). Red arrowheads indicate ILFs. Scale bar, 500 μm (A) and 100 μm (B).

(C) The number of colonic ILFs (upper panel) and the proportions of their subsets grouped according to size (lower panel) were determined. **p<0.005.

(D) The expression of the indicated genes in the intestinal epithelium of WT and IEC-IKKβEE mice was analyzed by qPCR. Data are shown as mean±SEM.

NF-κB-driven expression of GALT-related chemokines is regulated by p38α

A genome-wide expression analysis of the intestinal epithelium of IEC-IKKβEE mice identified numerous genes whose expression was elevated in IECs with constitutive NF-κB activation (12). Among these genes were Ltb, encoding the TNF family member lymphotoxin-β, and the chemokine genes Ccl20 and Cxcl16 (Fig. 6A). The contribution of lymphotoxin-β signaling to peripheral lymphoid tissue development is well established (10, 11). CCL20 and CXCL16, both expressed in the intestinal epithelium, have also been implicated in GALT formation in mice (31-34). By restraining NF-κB activation, p38α signaling might regulate the expression of these GALT-related NF-κB target genes in IECs. In keeping with this premise, Ccl20 and Cxcl16 expression was increased in the colonic epithelium of p38αΔIEC mice (Fig. 6B). On the other hand, the expression of Ltb and other genes encoding GALT-related or IEC-derived cytokines (Tnfsf13b, Il7, Tslp, Il25, and Il33) and chemokines (Cxcl13) was comparable in WT and p38αΔIEC colons (Fig. 6B).

Figure 6. Loss of p38α augments NF-κB-driven chemokine gene expression in intestinal epithelial cells.

(A) Intestinal epithelial cells from WT and IEC-IKKβEE mice (two animals for each genotype, #1 and #2) were subjected to DNA microarray analysis. Relative RNA amounts for differentially expressed genes are presented in color-coded arbitrary units. Select genes showing higher expression in cells from IEC-IKKβEE mice relative to WT counterparts are indicated on the right along with the ratios (fold change; FC) of their RNA amounts.

(B) The expression of the indicated genes in the colonic epithelium of WT and p38αΔIEC mice was analyzed by qPCR. Data for the colon are shown as mean±SEM.

(C-E) MODE-K cells were transfected with control and RelA- or p38α-specific siRNA (C, D), or with plasmids expressing control (V) and p38α-specific (#2) shRNA (E). Whole cell lysates were prepared and analyzed by immunoblotting (C). The expression of the indicated genes in TNF-treated cells was analyzed by qPCR (D, E).

To investigate in greater detail how the IKKβ-NF-κB axis and p38α signaling interact to shape gene expression in IECs, we examined the effects of siRNA- and shRNA-mediated RelA and p38α gene KD (Fig. 6C and Fig. 4A, respectively) on the expression of TNF-inducible genes in MODE-K cells. The expression of a majority of TNF-inducible genes was abolished by RelA gene KD (Fig. 6D). TNF induction of a subset of the genes whose expression depended on RelA, including Ccl20 and Cxcl16, was substantially enhanced by p38α gene KD (Fig. 6, D and E). These results suggested that the regulatory function of p38α was directed towards specific NF-κB target genes in IECs. In summary, the changes in intracellular signaling and gene expression that we identified from p38α-deficient IECs were consistent with ILF hyperplasia in p38αΔIEC mice, and suggested CCL20 and CXCL16 as two possible mediators that link epithelial protein kinase signaling to GALT formation.

Discussion

We have identified a novel, non-cell-autonomous role for p38α signaling in regulating GALT formation and maintenance. From an investigation of p38αΔIEC mice, we showed that genetic ablation of p38α signaling in IECs resulted in GALT hyperplasia, which became more prominent as the animals aged and predisposed to B cell malignancy. Mechanistically, p38α attenuated TAK1-NF-κB signaling in IECs and thereby regulated epithelial expression of GALT-promoting chemokines. These findings illustrate that epithelial genetic alterations can cause or predispose to lymphoid hyperplasia and malignancy in mucosal tissues.

IEC-restricted loss of p38α signaling led to a striking increase in postnatal colonic ILF growth but exerted lesser effects, if any, on prenatally developing GALT such as Peyer's patches. Both ILFs and Peyer's patches develop in a manner dependent on lymphotoxin-β receptor signaling and RORγt-driven gene expression (18, 19, 35-37), yet the genetic requirements for their formation are not identical (38, 39). Epithelial p38α signaling presumably regulates a mechanism specifically linked to ILF development. This regulation does not likely involve the GALT-promoting effect of the intestinal microbiota, given that colonic ILF hyperplasia persisted in antibiotic-treated p38αΔIEC mice. It is noteworthy that, although luminal bacteria in general promote postnatal GALT development, several studies reported that colonic ILF development was not impeded in germ-free and antibiotic-treated mice (33, 40-42). These findings indicate that the effects of intestinal microbiota are context-dependent, and do not intervene in the p38α-mediated IEC-GALT interaction in the colon.

GALT hyperplasia in humans has been reported in association with pathological conditions of diverse etiologies (43, 44). Little information is available regarding the molecular mechanisms underlying the clinically observed GALT anomalies. Intriguingly, recent studies uncovered a link of some genetic alterations with specific cases. In particular, human subjects with germline mutations that result in phosphoinositide 3-kinase hyperactivation (e.g. PTEN loss-of-function, PIK3CD gain-of-function) have been found to develop nodular lymphoid hyperplasia in the small intestine and colon (45, 46). In addition, studies of mice with a targeted gene deletion or mutation have shown that GALT hyperplasia can arise from impaired immunoglobulin diversification or deregulated non-canonical NF-κB signaling (20, 47). The genetic alterations investigated in these human and mouse studies led to an expansion of the B cell compartment in the GALT via cell-autonomous mechanisms, augmenting B cell proliferation, survival, or immune function. By contrast, our findings highlight the contribution of the epithelium as a niche to determining the size of B cell pools and other constituents of the GALT.

Loss of p38α signaling in IECs, while enhancing NF-κB activation, affected the expression of only a subset of NF-κB target genes, Ccl20 and Cxcl16 among others. Conceivably, additional signaling changes that paralleled NF-κB hyperactivation in p38α-deficient IECs (e.g. the loss of signaling downstream of p38α or the dysregulation of JNK or ERK signaling) might have an offsetting or overriding effect on NF-κB-driven gene expression; under such a circumstance, augmented NF-κB signaling in cells lacking p38α would not necessarily translate to an increase in global NF-κB target gene expression. We postulate that CCL20 and CXCL16 contribute to promoting GALT hyperplasia and malignancy in p38αΔIEC mice, yet do not exclude possible involvement of other gene products. CCR6 and CXCR6, the receptors for CCL20 and CXCL16, respectively, are expressed in ILF B cells (32) and LTi cells (48-51). Of note, it has been reported that CCR6 and CXCR6 are also highly expressed in clinical specimens of mucosa-associated B cell lymphoma, and that the epithelium neighboring the lymphoma expresses CCL20 (52, 53). The precise roles of the two chemokines in GALT and B cell homeostasis remain to be scrutinized. Further investigation of epithelial-lymphoid interactions in p38αΔIEC and IEC-IKKβEE mice may reveal novel IEC-derived molecular signals that produce various lymphoid tissue abnormalities in the intestinal mucosa.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Ila Joshi and Katia Georgopoulos for technical advice on the analysis of immunoglobulin gene rearrangement and germinal centers.

This study was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants AI074957 (to J.M.P.) and AI043477 (to M.K.).

Abbreviations used in this article

- DSS

dextran sulfate sodium

- GALT

gut-associated lymphoid tissue

- IEC

intestinal epithelial cell

- ILF

isolated lymphoid follicle

- KD

knockdown

- LTi

lymphoid tissue inducer

- PNA

peanut agglutinin

- TNF

tumor necrosis factor

References

- 1.Brewster JL, Gustin MC. Hog1: 20 years of discovery and impact. Sci. Signal. 2014;7:re7. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2005458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Trempolec N, Dave-Coll N, Nebreda AR. SnapShot: p38 MAPK signaling. Cell. 2013;152:656–656.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gupta J, Nebreda AR. Roles of p38α mitogen-activated protein kinase in mouse models of inflammatory diseases and cancer. FEBS J. 2015;282:1841–1857. doi: 10.1111/febs.13250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hui L, Bakiri L, Mairhorfer A, Schweifer N, Haslinger C, Kenner L, Komnenovic V, Scheuch H, Beug H, Wagner EF. p38α suppresses normal and cancer cell proliferation by antagonizing the JNK-c-Jun pathway. Nat. Genet. 2007;39:741–749. doi: 10.1038/ng2033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ventura JJ, Tenbaum S, Perdiguero E, Huth M, Guerra C, Barbacid M, Pasparakis M, Nebreda AR. p38α MAP kinase is essential in lung stem and progenitor cell proliferation and differentiation. Nat. Genet. 2007;39:750–758. doi: 10.1038/ng2037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sakurai T, He G, Matsuzawa A, Yu GY, Maeda S, Hardiman G, Karin M. Hepatocyte necrosis induced by oxidative stress and IL-1α release mediate carcinogen-induced compensatory proliferation and liver tumorigenesis. Cancer Cell. 2008;14:156–165. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Otsuka M, Kang YJ, Ren J, Jiang H, Wang Y, Omata M, Han J. Distinct effects of p38α deletion in myeloid lineage and gut epithelia in mouse models of inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:1255–1265. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Caballero-Franco C, Choo MK, Sano Y, Ritprajak P, Sakurai H, Otsu K, Mizoguchi A, Park JM. Tuning of protein kinase circuitry by p38α is vital for epithelial tissue homeostasis. J. Biol. Chem. 2013;288:23788–23797. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.452029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gupta J, del Barco Barrantes I, Igea A, Sakellariou S, Pateras IS, Gorgoulis VG, Nebreda AR. Dual function of p38α MAPK in colon cancer: suppression of colitis-associated tumor initiation but requirement for cancer cell survival. Cancer Cell. 2014;25:484–500. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pearson C, Uhlig HH, Powrie F. Lymphoid microenvironments and innate lymphoid cells in the gut. Trends Immunol. 2012;33:289–296. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2012.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Randall TD, Mebius RE. The development and function of mucosal lymphoid tissues: a balancing act with micro-organisms. Mucosal Immunol. 2014;7:455–466. doi: 10.1038/mi.2014.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guma M, Stepniak D, Shaked H, Spehlmann ME, Shenouda S, Cheroutre H, Vicente-Suarez I, Eckmann L, Kagnoff MF, Karin M. Constitutive intestinal NF-κB does not trigger destructive inflammation unless accompanied by MAPK activation. J. Exp. Med. 2011;208:1889–1900. doi: 10.1084/jem.20110242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vidal K, Grosjean I, Evillard JP, Gespach C, Kaiserlian D. Immortalization of mouse intestinal epithelial cells by the SV40-large T gene. Phenotypic and immune characterization of the MODE-K cell line. J. Immunol. Methods. 1993;166:63–73. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(93)90329-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shimomura Y, Ogawa A, Kawada M, Sugimoto K, Mizoguchi E, Shi HN, Pillai S, Bhan AK, Mizoguchi A. A unique B2 B cell subset in the intestine. J. Exp. Med. 2008;205:1343–1355. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fuxa M, Skok J, Souabni A, Salvagiotto G, Roldan E, Busslinger M. Pax5 induces V-to-DJ rearrangements and locus contraction of the immunoglobulin heavy-chain gene. Genes Dev. 2004;18:411–422. doi: 10.1101/gad.291504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Park JM, Ng VH, Maeda S, Rest RF, Karin M. Anthrolysin O and other gram-positive cytolysins are toll-like receptor 4 agonists. J. Exp. Med. 2004;200:1647–1655. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Enzler T, Sano Y, Choo MK, Cottam HB, Karin M, Tsao H, Park JM. Cell-selective inhibition of NF-κB signaling improves therapeutic index in a melanoma chemotherapy model. Cancer Discov. 2011;1:496–507. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-11-0143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hamada H, Hiroi T, Nishiyama Y, Takahashi H, Masunaga Y, Hachimura S, Kaminogawa S, Takahashi-Iwanaga H, Iwanaga T, Kiyono H, Yamamoto H, Ishikawa H. Identification of multiple isolated lymphoid follicles on the antimesenteric wall of the mouse small intestine. J. Immunol. 2002;168:57–64. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.1.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tsuji M, Suzuki K, Kitamura H, Maruya M, Kinoshita K, Ivanov II, Itoh K, Littman DR, Fagarasan S. Requirement for lymphoid tissue-inducer cells in isolated follicle formation and T cell-independent immunoglobulin A generation in the gut. Immunity. 2008;29:261–271. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fagarasan S, Muramatsu M, Suzuki K, Nagaoka H, Hiai H, Honjo T. Critical roles of activation-induced cytidine deaminase in the homeostasis of gut flora. Science. 2002;298:1424–1427. doi: 10.1126/science.1077336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pabst O, Herbrand H, Friedrichsen M, Velaga S, Dorsch M, Berhardt G, Worbs T, Macpherson AJ, Förster R. Adaptation of solitary intestinal lymphoid tissue in response to microbiota and chemokine receptor CCR7 signaling. J. Immunol. 2006;177:6824–6832. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.10.6824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lochner M, Ohnmacht C, Presley L, Bruhns P, Si-Tahar M, Sawa S, Eberl G. Microbiota-induced tertiary lymphoid tissues aggravate inflammatory disease in the absence of RORγt and LTi cells. J. Exp. Med. 2011;208:125–134. doi: 10.1084/jem.20100052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Savage DC, Dubos R. Alterations in the mouse cecum and its flora produced by antibacterial drugs. J. Exp. Med. 1968;128:97–110. doi: 10.1084/jem.128.1.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Olson TS, Bamias G, Naganuma M, Rivera-Nieves J, Burcin TL, Ross W, Morris MA, Pizarro TT, Ernst PB, Cominelli F, Ley K. Expanded B cell population blocks regulatory T cells and exacerbates ileitis in a murine model of Crohn disease. J. Clin. Invest. 2004;114:389–398. doi: 10.1172/JCI20855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kawamura T, Kanai T, Dohi T, Uraushihara K, Totsuka T, Iiyama R, Taneda C, Yamazaki M, Nakamura T, Higuchi T, Aiba Y, Tsubata T, Watanabe M. Ectopic CD40 ligand expression on B cells triggers intestinal inflammation. J. Immunol. 2004;172:6388–6397. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.10.6388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Adams DH, Eksteen B. Aberrant homing of mucosal T cells and extra-intestinal manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2006;6:244–251. doi: 10.1038/nri1784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang C, Deng L, Hong M, Akkaraju GR, Inoue J, Chen ZJ. TAK1 is a ubiquitin-dependent kinase of MKK and IKK. Nature. 2001;412:346–351. doi: 10.1038/35085597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shim JH, Xiao C, Paschal AE, Bailey ST, Rao P, Hayden MS, Lee KY, Bussey C, Steckel M, Tanaka N, Yamada G, Akira S, Matsumoto K, Ghosh S. TAK1, but not TAB1 or TAB2, plays an essential role in multiple signaling pathways in vivo. Genes Dev. 2005;19:2668–2681. doi: 10.1101/gad.1360605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pasparakis M. Role of NF-κB in epithelial biology. Immunol. Rev. 2012;246:346–358. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2012.01109.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vlantis K, Wullaert A, Sasaki Y, Schmidt-Supprian M, Rajewsky K, Roskams T, Pasparakis M. Constitutive IKK2 activation in intestinal epithelial cells induces intestinal tumors in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 2011;121:2781–2793. doi: 10.1172/JCI45349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hase K, Murakami T, Takatsu H, Shimaoka T, Iimura M, Hamura K, Kawano K, Ohshima S, Chihara R, Itoh K, Yonehara S, Ohno H. The membrane-bound chemokine CXCL16 expressed on follicle-associated epithelium and M cells mediates lympho-epithelial interaction in GALT. J. Immunol. 2006;176:43–51. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McDonald KG, McDonough JS, Wang C, Kucharzik T, Williams IR, Newberry RD. CC chemokine receptor 6 expression by B lymphocytes is essential for the development of isolated lymphoid follicles. Am. J. Pathol. 2007;170:1229–1240. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.060817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bouskra D, Brézillon C, Bérard M, Werts C, Varona R, Boneca IG, Eberl G. Lymphoid tissue genesis induced by commensals through NOD1 regulates intestinal homeostasis. Nature. 2008;456:507–510. doi: 10.1038/nature07450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Obata Y, Kimura S, Nakato G, Iizuka K, Miyagawa Y, Nakamura Y, Furusawa Y, Sugiyama M, Suzuki K, Ebisawa M, Fujimura Y, Yoshida H, Iwanaga T, Hase K, Ohno H. Epithelial-stromal interaction via Notch signaling is essential for the full maturation of gut-associated lymphoid tissues. EMBO Rep. 2014;15:1297–1304. doi: 10.15252/embr.201438942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.De Togni P, Goellner J, Ruddle NH, Streeter PR, Fick A, Mariathasan S, Smith SC, Carlson R, Shornick LP, Strauss-Schoenberger J, Russell JH, Karr R, Chaplin DD. Abnormal development of peripheral lymphoid organs in mice deficient in lymphotoxin. Science. 1994;264:703–707. doi: 10.1126/science.8171322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lorenz RG, Chaplin DD, McDonald KG, McDonough JS, Newberry RD. Isolated lymphoid follicle formation is inducible and dependent upon lymphotoxin-sufficient B lymphocytes, lymphotoxin β receptor, and TNF receptor I function. J. Immunol. 2003;170:5475–5482. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.11.5475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Eberl G, Marmon S, Sunshine MJ, Rennert PD, Choi Y, Littman DR. An essential function for the nuclear receptor RORγt in the generation of fetal lymphoid tissue inducer cells. Nat. Immunol. 2004;5:64–73. doi: 10.1038/ni1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Knoop KA, Butler BR, Kumar N, Newberry RD, Williams IR. Distinct developmental requirements for isolated lymphoid follicle formation in the small and large intestine: RANKL is essential only in the small intestine. Am. J. Pathol. 2011;179:1861–1871. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee JS, Cella M, McDonald KG, Garlanda C, Kennedy GD, Nukaya M, Mantovani A, Kopan R, Bradfield CA, Newberry RD, Colonna M. AHR drives the development of gut ILC22 cells and postnatal lymphoid tissues via pathways dependent on and independent of Notch. Nat. Immunol. 2011;13:144–151. doi: 10.1038/ni.2187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kweon MN, Yamamoto M, Rennert PD, Park EJ, Lee AY, Chang SY, Hiroi T, Nanno M, Kiyono H. Prenatal blockage of lymphotoxin beta receptor and TNF receptor p55 signaling cascade resulted in the acceleration of tissue genesis for isolated lymphoid follicles in the large intestine. J. Immunol. 2005;174:4365–4372. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.7.4365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Baptista AP, Olivier BJ, Goverse G, Greuter M, Knippenberg M, Kusser K, Domingues RG, Veiga-Fernandes H, Luster AD, Lugering A, Randall TD, Cupedo T, Mebius RE. Colonic patch and colonic SILT development are independent and differentially regulated events. Mucosal Immunol. 2013;6:511–521. doi: 10.1038/mi.2012.90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Donaldson DS, Bradford BM, Artis D, Mabbott NA. Reciprocal regulation of lymphoid tissue development in the large intestine by IL-25 and IL-23. Mucosal Immunol. 2015;8:582–595. doi: 10.1038/mi.2014.90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mansueto P, Iacono G, Seidita A, D'Alcamo A, Sprini D, Carroccio A. Intestinal lymphoid nodular hyperplasia in children--the relationship to food hypersensitivity. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2012;35:1000–1009. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2012.05062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Albuquerque A. Nodular lymphoid hyperplasia in the gastrointestinal tract in adult patients: A review. World J. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2014;6:534–540. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v6.i11.534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Heindl M, Händel N, Ngeow J, Kionke J, Wittekind C, Kamprad M, Rensing-Ehl A, Ehl S, Reifenberger J, Loddenkemper C, Maul J, Hoffmeister A, Aretz S, Kiess W, Eng C, Uhlig HH. Autoimmunity, intestinal lymphoid hyperplasia, and defects in mucosal B-cell homeostasis in patients with PTEN hamartoma tumor syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:1093–1096. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lucas CL, Kuehn HS, Zhao F, Niemela JE, Deenick EK, Palendira U, Avery DT, Moens L, Cannons JL, Biancalana M, Stoddard J, Ouyang W, Frucht DM, Rao VK, Atkinson TP, Agharahimi A, Hussey AA, Folio LR, Olivier KN, Fleisher TA, Pittaluga S, Holland SM, Cohen JI, Oliveira JB, Tangye SG, Schwartzberg PL, Lenardo MJ, Uzel G. Dominant-activating germline mutations in the gene encoding the PI(3)K catalytic subunit p110δ result in T cell senescence and human immunodeficiency. Nat. Immunol. 2014;15:88–97. doi: 10.1038/ni.2771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Conze DB, Zhao Y, Ashwell JD. Non-canonical NF-κB activation and abnormal B cell accumulation in mice expressing ubiquitin protein ligase-inactive c-IAP2. PLoS Biol. 2010;8:e1000518. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lügering A, Ross M, Sieker M, Heidemann J, Williams IR, Domschke W, Kucharzik T. CCR6 identifies lymphoid tissue inducer cells within cryptopatches. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2010;160:440–449. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2010.04103.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sawa S, Cherrier M, Lochner M, Satoh-Takayama N, Fehling HJ, Langa F, Di Santo JP, Eberl G. Lineage relationship analysis of RORgammat+ innate lymphoid cells. Science. 2010;330:665–669. doi: 10.1126/science.1194597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Possot C, Schmutz S, Chea S, Boucontet L, Louise A, Cumano A, Golub R. Notch signaling is necessary for adult, but not fetal, development of RORγt+ innate lymphoid cells. Nat. Immunol. 2011;12:949–958. doi: 10.1038/ni.2105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Satoh-Takayama N, Serafini N, Verrier T, Rekiki A, Renauld JC, Frankel G, Di Santo JP. The chemokine receptor CXCR6 controls the functional topography of interleukin-22 producing intestinal innate lymphoid cells. Immunity. 2014;41:776–788. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rodig SJ, Jones D, Shahsafaei A, Dorfman DM. CCR6 is a functional chemokine receptor that serves to identify select B-cell non-Hodgkin's lymphomas. Hum. Pathol. 2002;33:1227–1233. doi: 10.1053/hupa.2002.129417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Deutsch AJ, Steinbauer E, Hofmann NA, Strunk D, Gerlza T, Beham-Schmid C, Schaider H, Neumeister P. Chemokine receptors in gastric MALT lymphoma: loss of CXCR4 and upregulation of CXCR7 is associated with progression to diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Mod. Pathol. 2013;26:182–194. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2012.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.