Abstract

An intramesosigmoid hernia is 1 of the 3 rare types of sigmoid-related hernias that could be complicated by intestinal obstruction. Our patient presented with a clinical picture of intestinal obstruction. CT scan showed features of strangulated small-bowel obstruction secondary to a sigmoid-related hernia. This was confirmed intraoperatively to be an intramesosigmoid hernia. We share the radiological findings with intraoperative surgical correlation and discuss the imaging features described in the literature.

Background

Small-bowel obstruction in a virgin abdomen is a surgical emergency and often radiological investigations are requested preoperatively. Internal hernias only account for 6% of intestinal obstruction cases1 and 6% of internal hernias are due to sigmoid-related hernias.2 As such, an awareness of the radiological features of this rare condition, including its complications will allow an accurate diagnosis to be made thereby assisting surgical planning. In addition, patients with findings of an internal hernia causing intestinal obstruction after a CT scan are much more likely to be operated on.3

Case presentation

A 75-year-old male patient presented to the emergency department with a 3-day history of generalised colicky abdominal pain, constipation and vomiting. He had no history of abdominal surgery.

On arrival, he was tachycardic with a pulse rate of 120 bpm. He was febrile and his blood pressure was 111/60 mm Hg. On physical examination, his abdomen was non-tender but slightly distended. A digital rectal examination showed impacted stools without any blood.

Investigations

Laboratory studies revealed that serum lactate was elevated at 4.6 mmol/L and the total white cell count was normal at 6.8×109/L.

The plain abdominal radiograph showed dilation of the continuous loops of small intestines with a distal transition point (figure 1) and multiple air–fluid levels in the small intestine due to small intestinal obstruction. An emergency abdominal and pelvic CT scan with rectal contrast was arranged. No intravenous contrast was administered due to acute renal failure. The CT scan showed a C-shaped small bowel loop in an abnormal location posterior and lateral to the sigmoid colon, and anterior to the left psoas muscle (figures 2–4). It displaced the sigmoid colon medially and anteriorly. The C-shaped small intestine had a tight narrowing at the mesosigmoid (figures 3–5). These features were suspicious for internal herniation of the small bowel loop possibly because of a defect in the sigmoid mesentery. This was associated with fat stranding adjacent to the herniated loops raising the possibility of strangulation (figure 2) although further assessment of bowel wall viability was difficult in the absence of intravenous contrast. No intramural or portal venous gas was however detected. Proximal to the hernia the small bowel loops were dilated due to mechanical obstruction.

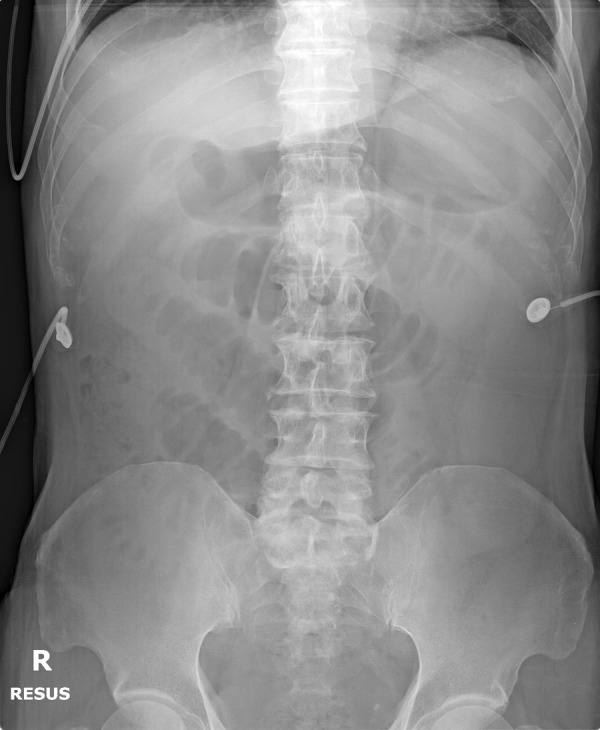

Figure 1.

The supine abdominal radiograph of the patient showing several dilated small intestinal loops, suspicious for small-bowel obstruction with a distal transition zone. There is no evidence of overt pneumoperitoneum.

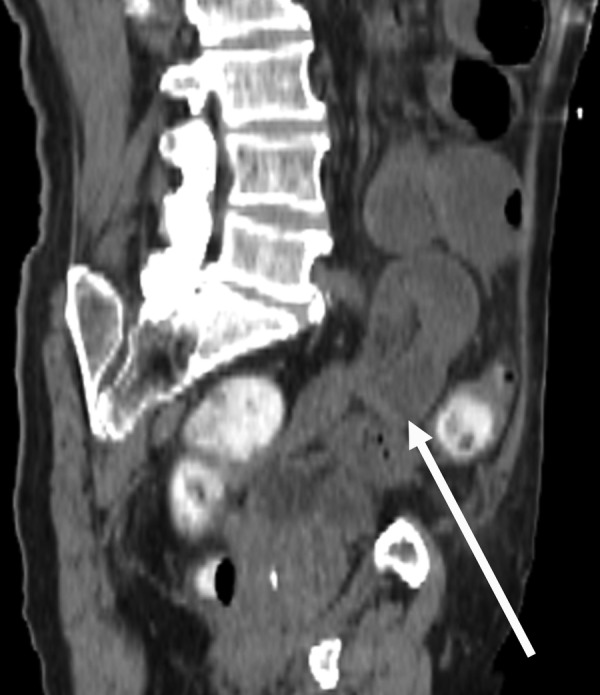

Figure 2.

The unenhanced coronal CT image showing a C-shaped appearance of the dilated small bowel (white arrow) with mesenteric engorgement and fat stranding suggestive of strangulation.

Figure 3.

The oblique reformatted CT image better demonstrating the herniated loop of small bowel (white arrow) with a transition zone.

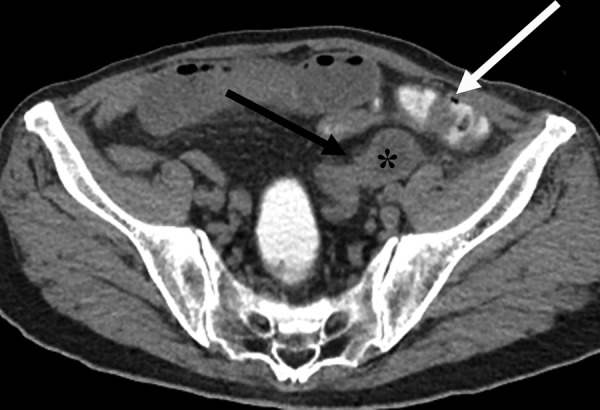

Figure 4.

The axial CT image showing the dilated small bowel (*) in an abnormal position, posterolateral to the sigmoid colon that contains intraluminal contrast (white arrow). Its transition zone points medially (black arrow) with a beak-like appearance.

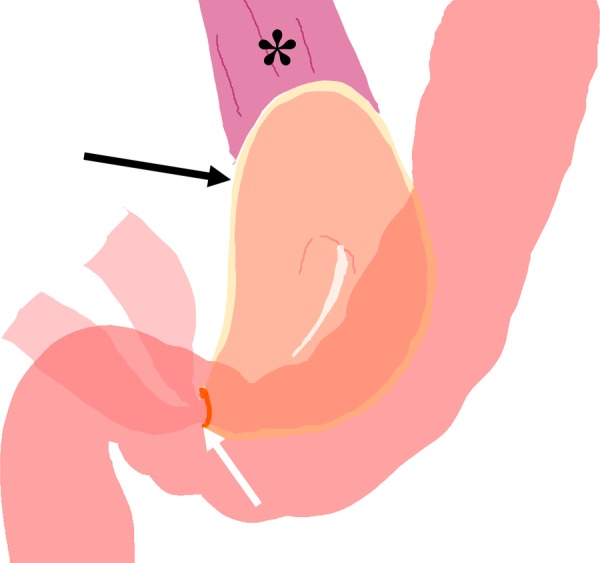

Figure 5.

A diagrammatic illustration showing the anatomical relationship of the bowel loops in an intramesosigmoid hernia. The bowel herniates through a defect in the medial leaf of the mesocolon (white arrow) into a sac formed by the lateral leaf of the mesocolon (black arrow). The herniated bowel is found anterior to the left psoas muscle (*) and posterior to the sigmoid.

Treatment

The patient was resuscitated and stabilised. A decision was then made for emergency surgical intervention based on a working diagnosis of strangulated small bowel sigmoid-related hernia (CT scan findings) with possible bowel ischaemia/gangrene (raised serum lactate). The options of exploratory laparotomy versus laparoscopic surgery were considered. In view of the possible need for bowel resection and to avoid inadvertent injury to the normal but dilated bowel loops (during entry into the abdomen and bowel manipulation), an exploratory laparotomy was performed.

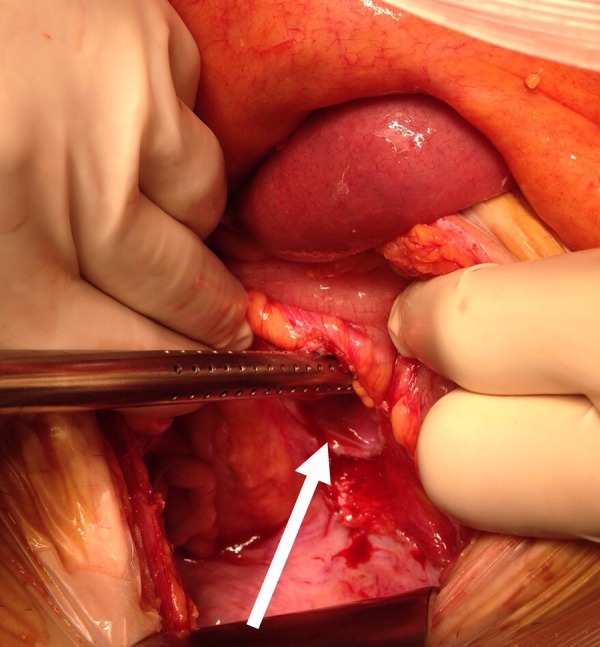

Intraoperatively, a 10 cm long segment of ischaemic small bowel was found to have been herniated through a 3 cm defect in the medial leaf of the mesosigmoid (figure 6) and was bound by the lateral leaf of the mesosigmoid that formed the lateral hernial wall (figure 5). The ischaemic small bowel was located 1 m from the ileocaecal valve.

Figure 6.

An intraoperative photograph showing the defect in the medial leaf of the mesocolon (white arrow), through which the discoloured ischaemic small bowel had herniated through.

The ischaemic small bowel was resected, followed by functional end-to-end anastomosis and repair of the sigmoid mesenteric defect.

Outcome and follow-up

The patient made an uneventful recovery. After discharge, he was able to maintain his instrumental activities of daily living.

Discussion

Internal and sigmoid hernias

An internal hernia is a visceral protrusion through the peritoneum or mesentery into the peritoneal cavity.1 2 Its orifice may be congenital or acquired. The overall incidence of internal hernias resulting in intestinal obstruction can be up to 6%1 and it can be further divided according to their topographical distribution.2

Sigmoid hernias account for ∼6% of internal hernias2 and they are the second rarest form of internal hernias.4 The sigmoid colon is attached to the pelvic wall by the sigmoid mesocolon, which is a peritoneal fold. The apex of the fold is divided near the left common iliac artery, serving as a potential herniation site.2

Majority of the sigmoid-related hernias occur in adults while only a few are reported in children.5 Y Nihon-Yanag reported that intersigmoid and intramesosigmoid hernias were more commonly seen in men, probably due to the anatomical differences in the pelvis. No gender preponderance is noted in transmesosigmoid hernias.

Types of sigmoid-related hernias

There are three generally accepted subtypes of sigmoid-related hernias: (1) intersigmoid hernia has bowel protruding into a congenital intersigmoid fossa. This fossa is formed between two adjacent sigmoid segments, of which their lateral surfaces are fused with the parietal peritoneum of the abdominal wall. It is the commonest type of sigmoid-related hernia in the West and is reportedly found in 65% of autopsies.1 It is often easily reducible;6 (2) transmesosigmoid hernia has the bowel herniating through both layers of the mesocolon to lie posterolateral to the sigmoid and the orifice is bound by branches of the inferior mesenteric artery.1 Hence, no hernial sac is formed; and (3) intramesosigmoid hernia is the rarest type in the Western literature but the commonest type in the Japanese literature.5 The viscus herniates through an incomplete defect found on only one layer of the mesosigmoid. Thus, the hernial sac lies within the sigmoid mesocolon1 as seen in our case.

Anatomical features

The literature may reveal a pattern relating the length of a herniated bowel with the type of sigmoid-related hernia. Intersigmoid and intramesosigmoid hernias have similar average lengths of 8.4 and 10.2 cm respectively,5 which is similar to our intramesosigmoid hernia case. Both types of hernia can present with a herniated bowel length up to 50 cm.

An exception is an intramesosigmoid hernia case reported by Liao et al, where the herniated small bowel measured 280 cm in length. However, it had an atypical presentation of anterior herniation, whereas the classic intramesosigmoid hernia shows posterolateral herniation.

Unlike the intersigmoid and intramesosigmoid hernias, the average length of the transmesosigmoid hernia is much longer at 111.7 cm,5 which may make the finding of a long segment of herniated small bowel a useful tool in distinguishing it from the other two types of hernias, namely the intersigmoid and intramesosigmoid hernias.

The sigmoid-related hernias have orifice sizes ranging from 1.8 to 5.7 cm.5 7–10 However, the hernial orifice size is not a useful distinguishing feature of the subtypes.5

Further radiological features

In patients presenting with bowel obstruction, identifying the cause accurately allows for appropriate management and potentially shortens the surgical time. Additionally, sigmoid-related hernias can cause strangulation of the herniated intestine and bowel necrosis.

A CT scan is the preferred modality to assess the cause of bowel obstruction and to diagnose an obstructed sigmoid-related hernia. However, it may be difficult to identify it preoperatively, and much less categorise the sigmoid hernia further into the three subtypes. Surgical exploration is still required4 and should not be delayed.

The level of bowel obstruction is often at the level of the mid to distal ileum in the left iliac fossa.5 8 10 A normal sigmoid colon should not have small bowel loops posterior and lateral to it (figure 4), hence if this is observed, a suspicion is raised.

In obstructed hernias, a Y-shaped and X-shaped dilated small bowel can be detected between the sigmoid colon and the left psoas muscle in sigmoid-related hernias or between the sigmoid colon in the intersigmoid type.1 A bird's beak transition point of the herniated bowel pointing medially was also thought to be highly suggestive of the sigmoid-related hernias.10

There are atypical appearances as reported previously for an intramesosigmoid hernia, where the herniated bowel loops displaced the sigmoid colon posteriorly and superiorly instead.6 In this case, the CT angiogram showed supporting findings of redirection of the vessels that accompany the herniated small bowel with splaying of the sigmoid arteries.

Barium studies may be useful in demonstrating uncomplicated sigmoid-related hernias. Small bowel barium studies can demonstrate a stricture in the small intestine5 or the distended small bowel loop trapped between the sigmoid colon.4 The postevacuation barium enema study may show sacculated ileal loops in the left lower abdomen associated with elevation and right lateral displacement of the sigmoid colon.9 Barium studies are however contraindicated in acute bowel obstruction.

Management

Prompt surgical intervention is the treatment of choice in a patient with bowel obstruction secondary to internal hernia due to the risk of strangulation and necrosis.10 Regardless of whether a more traditional laparotomy6 10 11 or increasingly popular laparoscopic approach is performed, the herniated bowel is reduced or resected if non-viable and the mesocolon is usually closed.

There are recent reports of successful laparoscopic approach, particularly for diagnostic purposes for sigmoid-related hernias that are complicated by obstruction and are non-gangrenous.7–11 Laparoscopic repair of hernias is notably more difficult to perform,12 13 particularly when the small working space is further limited by dilated bowel loops and there is a lack of tactile feedback. In the event of bowel gangrene, conversion to laparotomy is still required10 and hence if there is high preoperative suspicion of gangrene, a laparotomy approach in an emergency setting will still be prudent.

Learning points.

Sigmoid-related hernia is a rare type of internal hernia that can cause intestinal obstruction and its associated complications.

CT is the imaging modality of choice to determine the cause of intestinal obstruction.

Although sigmoid-related hernias may be identifiable on a CT scan, the three subtypes may be indistinguishable.

Suggestive features on cross-sectional imaging are the presence of dilated bowel in an abnormal location between the sigmoid colon and the left psoas muscle with a bird's beak appearance of the transition zone pointing medially.

Operative management involves reduction of the herniated bowel and closure of the defect in the sigmoid mesocolon either via open or laparoscopic approach.

Footnotes

Contributors: SRSR and SWK identified the case and were involved in reporting the patient's CT scan. JW-ML was involved in the patient's surgery and management. SMHM, is a body imaging specialist, who helped in drafting and revising the study. All four authors meet the ICMJE recommendations, namely: have substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work or the acquisition or interpretation of data. Drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content. Final approval of the version published. Agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Martin LC, Merkle EM, Thompson WM. Review of internal hernias: radiographic and clinical findings. Am J Roentgenol 2006;186:703–17. 10.2214/AJR.05.0644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Takeyama N, Gokan T, Ohgiya Y et al. CT of internal hernias. Radiographics 2005;25:997–1015. 10.1148/rg.254045035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frasure SE, Hildreth A, Takhar S et al. Emergency department patients with small bowel obstruction: what is the anticipated clinical course? World J Emerg Med 2016;7:35–9. 10.5847/wjem.j.1920-8642.2016.01.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mathieu D, Luciani A. Internal abdominal herniations. Am J Roentgenol 2004;183:397–404. 10.2214/ajr.183.2.1830397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nihon-Yanagi Y, Ooshiro M, Osamura A et al. Intersigmoid hernia: report of a case. Surg Today 2010;40:171–5. 10.1007/s00595-009-4010-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liao YH, Lin CH, Hsieh WJ et al. Intramesosigmoid hernia: preoperative diagnostic MDCT findings. Abdom Imaging 2012;37:561–5. 10.1007/s00261-011-9806-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Agarwal A, Ray U, Hossain MZ et al. Congenital intra-mesosigmoid hernia—a case report of a rare sigmoid mesocolon hernia. Indian J Surg 2011;73:450–2. 10.1007/s12262-011-0275-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang C, Kim D. Small bowel obstruction caused by sigmoid mesocolic hernia. J Surg Case Rep 2014;2014:rju036. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/jscr/rju036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yu CY, Lin CC, Yu JC et al. Strangulated transmesosigmoid hernia: CT diagnosis. Abdom Imaging 2004;29:158–60. 10.1007/s00261-003-0095-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jimmy J, Wani SV, Shetty VV et al. Laparoscopic management of small bowel obstruction caused by a Sigmoid Mesocolic hernia. J Minim Access Surg 2011;7:236 10.4103/0972-9941.85647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kan H, Suzuki H, Takasaki H et al. A case of intramesosigmoid hernia. J Nippon Med Sch 2009;76;13–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meyer A, Blanc P, Kassir R et al. Laparoscopic hernia: umbilical-pubis length versus technical difficulty. JSLS 2014;18: e2014.00078 10.4293/JSLS.2014.00078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Assenza M, Rossi D, Rossi G et al. Laparoscopic management of left paraduodenal hernia. Case report and review of literature. G Chir 2014;35:185–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]