Abstract

Aldosterone, which plays a key role in maintaining water and electrolyte balance, is produced by zona glomerulosa cells of the adrenal cortex. Autonomous overproduction of aldosterone from zona glomerulosa cells causes Primary hyperaldosteronism. Recent clinical studies have highlighted the pathologic role of the KCNJ5 potassium channel in Primary hyperaldosteronism. Our objective was to determine whether Small-conductance Ca2+-activated potassium channels may also regulate aldosterone secretion in human adrenocortical cells. We found that apamin, the prototypic inhibitor of Small-conductance Ca2+-activated potassium channels, decreased membrane voltage, raised intracellular Ca2+ and dose-dependently increased aldosterone secretion from human adrenocortical H295R cells. By contrast, 1-EBIO, an agonist of small-conductance calcium-activated potassium channels, antagonized apamin's action and decreased aldosterone secretion. Commensurate with an increase in aldosterone production, apamin increased mRNA expression of steroidogenic acute regulatory protein and aldosterone synthase, that control the early and late rate-limiting steps in aldosterone biosynthesis respectively. In addition, apamin increased angiotensin II-stimulated aldosterone secretion, whereas 1-EBIO suppressed both angiotensin II- and high K+-stimulated production of aldosterone in H295R cells. These findings were supported by apamin-modulation of basal and angiotensin II-stimulated aldosterone secretion from acutely prepared slices of human adrenals. We conclude that small-conductance calcium-activated potassium channel activity negatively regulates aldosterone secretion in human adrenocortical cells. Genetic association studies are necessary to determine if mutations in Small-conductance Ca2+-activated potassium channel subtype 2 genes may also drive aldosterone excess in Primary hyperaldosteronism.

Keywords: SK channels, aldosterone secretion, adrenocortical cells, apamin, Primary hyperaldosteronism

Introduction

Aldosterone, plays a key role in the regulation of blood pressure, and is produced by zona glomerulosa (ZG) cells of the adrenal gland. The two primary physiologic aldosterone secretagogues, angiotensin II (Ang II) and potassium, increase aldosterone production in a Ca2+ dependent manner; extracellular Ca2+ entry into ZG cells is necessary to maintain stimulated secretion1-5. The contribution of plasma membrane voltage-gated Ca2+ channels to this obligate rise in intracellular Ca2+ is enabled by membrane depolarization, an action that is evoked by both Ang II and high potassium6.

Primary hyperaldosteronism (PA), caused by autonomous overproduction of aldosterone, is the most common form of endocrine hypertension with an incidence of approximately 10% among hypertensives7. Aldosterone producing adenoma (APA) and bilateral idiopathic primary hyperaldosteronism (IHA), the two most common subtypes of PA, account for ∼95% of clinically diagnosed cases8, 9. Patients with PA have increased cardiovascular risks than those with equivalent essential hypertension9-12. Notably, recent clinical studies have highlighted the pathologic role of KCNJ5 potassium channels in PA. Choi et al. first reported that two somatic mutations, G151R and L168R, in the inward rectifying potassium channel KCNJ5 were found in 8 of 22 aldosterone producing adenomas, and that an inherited T158A mutation was identified in patients with familial hyperaldosteronism (FH) type III13. Subsequent studies by other research groups have found additional mutations in KCNJ5 including G151E14, insT14915 and I157del16 that are associated with PA. Most of the identified mutations are located in the selectivity filter of the KCNJ5 channel protein, producing loss of channel selectivity for K+ with commensurate Na+ influx, that results in cell membrane depolarization, elevation of intracellular Ca2+ level, and the overproduction of aldosterone13, 14, 17.

Small-conductance Ca2+-activated potassium (SK) channels consist of three subtypes: SK1, SK2 and SK3, and are gated solely by intracellular Ca2+ elevation18. SK channels are widely expressed in the brain, contribute to the mAHP of neurons, and the regulation of various brain activities such as sleep, learning and memory (for review, see reference19). Choi's study suggested that human ZG cells may express SK channels13, but their function in ZG cells remains undefined. Activation of SK channels by an intracellular Ca2+ rise causes membrane hyperpolarization, an event that would oppose both Ang II and high K+ induced aldosterone secretion. Therefore, SK channels may play an important role in regulating aldosterone production.

In this study we assessed the contribution of SK channels to the control of basal and stimulated aldosterone production in Human adrenocortical H295R cells and in ZG cells within adrenal slices. To test the functional importance of SK channels to the regulation of aldosterone production, we manipulated channel activity pharmacologically using apamin, a prototypical inhibitor, and/or 1-EBIO, an agonist of SK channels, or genetically using lentiviral vector delivery of shRNA.

Methods

Cell culture and Chemicals

Human adrenocortical cell line H295R ( American Type Culture Collection) was cultured in DMEM / F12 medium (GIBCO) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, GIBCO), 1% antibiotic antimycotic solution and 0.1% ITS+ premix (BD Biosciences). 12h before the experiment, cells were serum deprived in DMEM/F12 containing 0.1% FBS. Reagents were purchased from TOCRIS (Apamin and 1-EBIO), Sigma Aldrich (Angiotensin II and nifedipine) and Alomone labs ( TTAP2 ).

RNA extraction and quantitative real-time PCR

Total RNA was extracted (RNeasy mini kit, QIAGEN) and reverse transcribed (2 μg RNA). RT-PCR was performed in 20 μl reactions containing: 2 μl of template, 0.4 μmol/L of each paired primer and SYBR Green PCR master mix. The thermocycling conditions were: 94 °C, 10min; 38 cycles of 94 °C, 30 s; 55 °C, 30 s; 72 °C, 30 s; 72 °C, 8 min. Results were normalized by β–actin mRNA, or in lentiviral infection, HPRT (hypoxanthine phosphoribosyltransferase ) mRNA. Data were calculated by 2-ΔΔCt method and reported as fold change over control. The primers used for real-time PCR are listed in Supplemental Table S1.

Electrophysiology

H295R whole-cell currents were recorded using an Axonpatch 200B or 700B amplifier (Axon Instruments). The bath solution contained (in mmol/L): 116 NaCl, 2 KCl, 10 HEPES, 2 MgCl2, 2 CaCl2, 10 Glucose, 20 TEACl and 5 4-aminopyridine, pH 7.4 (adjusted with NaOH). The internal solution contained (in mmol/L) 135 K Gluconate, 10 KCl, 10 HEPES, 10 EGTA, 1 CaCl2, 1 MgCL2, 2 Mg-ATP, pH adjusted to 7.3 using KOH. In some studies (Supplemental Figure S1) we used solutions that augmented the recorded SK currents (see online supplement). For calcium current recording, the bath solution contained (in mmol/L): 143 TEACl, 10 CaCl2, 2 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, 10 glucose, pH 7.4 (adjusted with TEAOH). The internal solution contained (in mmol/L): 125 CsCl, 10 HEPES, and 10 EGTA, 1 MgCl2, 1 CaCl2, 5 Mg-ATP, 0.3 Tris-GTP (pH adjusted to 7.2 using CsOH). For current clamp recording, the bath solution contained (in mmol/L):140 NaCl, 3 KCl, 10 HEPES, 2 MgCl2, 2 CaCl2, and 10 glucose (pH 7.3). The internal solution contained (in mmol/L):135 KMeSO3, 4 NaCl, 10 HEPES, 1 MgCl2, 0.5 EGTA, 3 Mg-ATP, and 0.3 Tris-GTP (pH 7.2). Recording pipettes (capillary tubing, BRAND) had resistances of 3-7MΩ under solution conditions. All recordings were performed at RT. Currents were sampled at 10 kHz and filtered at 2 kHz. Modulators were applied by gravity perfusion.

Steroid assay

Cell culture supernatants collected after treatment were stored at -80°C. Medium aldosterone concentrations were analyzed using an Aldosterone ELISA Kit (ENZO Life Science) following the manufacturer's recommendations. Results were normalized by total protein (BCA Protein Kit , GeneRay).

Measurement of intracellular Ca2+ levels

Intracellular Ca2+ was detected using fura-2 AM as previous reported20. Briefly, after serum starvation for 12h, cells were incubated in fresh 0.1% serum DMEM/F12 with/without 1 nmol/L apamin , washed twice with balanced salt solution (BSS). (BSS) buffer (in mmol/L): NaCl 145, KCl 2.5, HEPES 10, MgCl2 1, glucose 10, CaCl2 2. Subsequently, cells were incubated in BSS containing 10 μmol/L fura-2 AM (37°C, 45 min), washed three times with BSS, and fluorescence captured at 505 nm following excitation at 340 nm and 380 nm. Basal Ca2+ signal was acquired for 30s before the application of Angiotensin II (10 nmol/L, with 0.05% BSA) or high K+ (22 mmol/L) by pressure delivery (ALA). Fluorescence intensity was quantified using Metafluor software (Universal Imaging Corporation).

Plasmids and Lentiviral production

The shRNA hairpin sequences were inserted into MluI-ClaI sites of pLVTHM targeting vector as previous reported 21. Oligonucleotides specifying the shRNA are 5′-GAA GCT AGA ACT TAC CAA A-3′ and scramble, 5′-AAG GAT ACA CCG ATA ACA T-3′. Lentivirus was produced in the 293T cells using a packaging vector psPAX2 and an envelope plasmid pMD2.G. The viral supernatant was harvested after 48-72 h, and centrifuged at low speed to remove cellular debris. The virus was collected by ultra-centrifugation at 4°C and resuspended with PBS containing 0.1% BSA for storage at -80 °C.

Lentivirus infection was performed 24h after seeding H295R cells with 5 μg / μl Polybrene (added during infection) to complete medium. 72h after infection, cells were serum deprived for 12h using low-serum (0.1%) DMEM/F12, and then the medium replaced with or without apamin. After incubation (24h), supernatants were collected for measurement of aldosterone, and cells for measurement of mRNA.

Immunofluorescence and aldosterone secretion of human adrenal gland

Adrenal gland samples were obtained from 11 patients (5 male, 6 female, age 31-67) undergoing radical nephrectomy to remove kidney cancer and adjacent ipsilateral adrenal. The protocol for obtaining and using human adrenal tissues in this work was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Fudan University Shanghai Cancer Center, Fudan University. Written informed consent from all patients was obtained.

Human adrenal samples were transported in cold PBS. Fat tissue was removed, and adrenals were kept in ice-cold bicarbonate-buffered saline (BBS) containing (in mmol/L): 140 NaCl, 2 KCl, 0.1 CaCl2, 5 MgCl2, 26 NaHCO3 and 10 Glucose, bubbled with 95% O2 and 5% CO2. Tissue was embedded in low–melting temperature agar (2.5% in BBS, 10mm × 10mm), and sectioned (200μm, DSK microslicer, DOSAKA). The slices were placed on Millicell-CM membranes (pore size 0.4um; Millipore), and incubated in MEM Hanks (GIBCO) supplemented with (in mmol/L) 1 L-Glutamine, 1 CaCl2, 2 MgCl2, 30 HEPES, 12.8 Glucose, 5.24 NaHCO3, 12mg/L bovine insulin, 0.12% Ascorbic acid and 20% Horse serum (GIBCO), at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 2h before 6h treatment with the indicated agents.

For immunofluorescence, adrenal glands were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (12h-16h at 4°C), and transferred sequentially to: 10%, 20% and 30% sucrose/PBS at 4°C. After OCT embedding, tissues were sectioned (20μm, Leica CM1950 cryostat) and dried at room temperature (RT). Slices were fixed in 4% PFA for 15min at RT, washed (cold PBS), and incubated in 0.5% PBST for 10min. Slices were blocked (10% horse serum, 0.3% Triton X-100 in PBS, 2h, RT), and then incubated with primary antibody: rabbit anti-KCNN2 (1:200, Alomone Labs), 1% horse serum, 0.3% Triton X-100 in PBS, 1 day, 4°C. After washing with PBS, slices were incubated in the secondary antibody (Cy3-labled goat anti-rabbit IgG, 1:500, Beyotime, China) overnight, 4°C, washed with PBS, and DAPI treated before coverslipping. Confocal images were obtained using a Leica SP2 confocal microscope. For blocking studies, the KCNN2 peptide antigen was added (1:1) to the primary antibody solution.

All protocols were in accordance with institutional guidelines.

Statistics

Data analysis was performed with Clampfit 10.2 (Axon Instruments) and Origin 8.0 software (OriginLab). Statistical analysis consisted of unpaired or paired Student's t tests. Data are given as means ± S.E.M, n indicates the number of tested cells or independent tests. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Multiple comparisons were analyzed using a one-way ANOVA followed by post-hoc Tukey testing.

Results

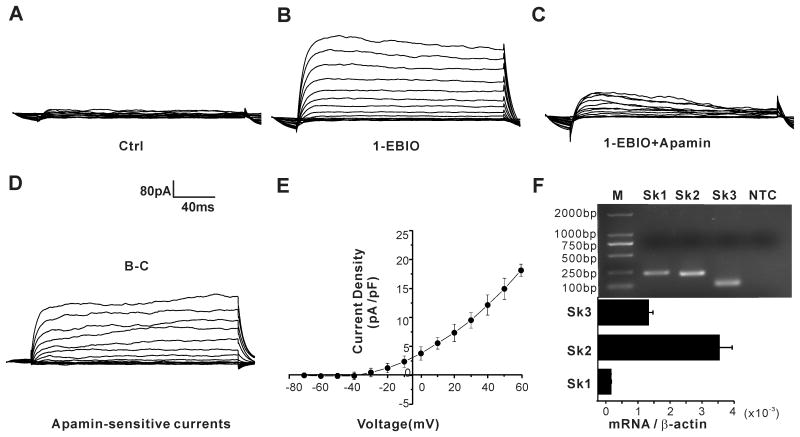

H295R cells express SK channels

A previous study suggested that the human adrenal cortex may express SK channels13. Therefore, we tested for SK channel mRNA expression in the human adrenocortical cell line H295R. As shown in Fig. 1F, mRNA for SK1, SK2 and SK3 was detected in H295R cells. All bands corresponded to the predicted product sizes generated from genes KCNN1-3, and their SK channel identity was confirmed by sequencing.

Figure 1. H295R cells express functional SK channels.

(A-C) representative K+ current traces in the absence and presence of SK channel activator 1-EBIO, or inhibitor apamin. (D) Apamin-sensitive SK channel currents obtained by subtracting C from B. (E) Current-voltage relationship (I–V curves) generated from peak current density at each test voltage. Data are presented as means ± S.E.M. from 10 cells. (F) SK1, SK2 and SK3 channel mRNA expression were detected in H295R cells by RT-PCR. NTC: no template control.

To determine if functional SK channels are expressed in H295R cells, we recorded K+ currents (Fig. 1A-E), and used pharmacological manipulation with apamin, the prototypical SK channel inhibitor, or 1-EBIO, an SK channel agonist, to identify SK channel currents . K+ currents elicited by 10-mV depolarizing steps from a holding potential of −95 mV elicited outward currents of small magnitude (Fig. 1A). Although small, the elicited whole-cell currents were amplified robustly by 1-EBIO (100 μmol/L), a modulation that could be antagonized by apamin (100 nmol/L). A determination of the apamin-sensitive component of 1-EBIO induced currents (AS-1EBIO) pharmacologically isolated the SK-component of current. We note that because our standard recording solutions contained high TEA in the bath and EGTA in the internal, the measured SK-component of current was modestly diminished in agreement with the 17% increase observed (Supplemental Figure S1) when TEA and EGTA were removed.

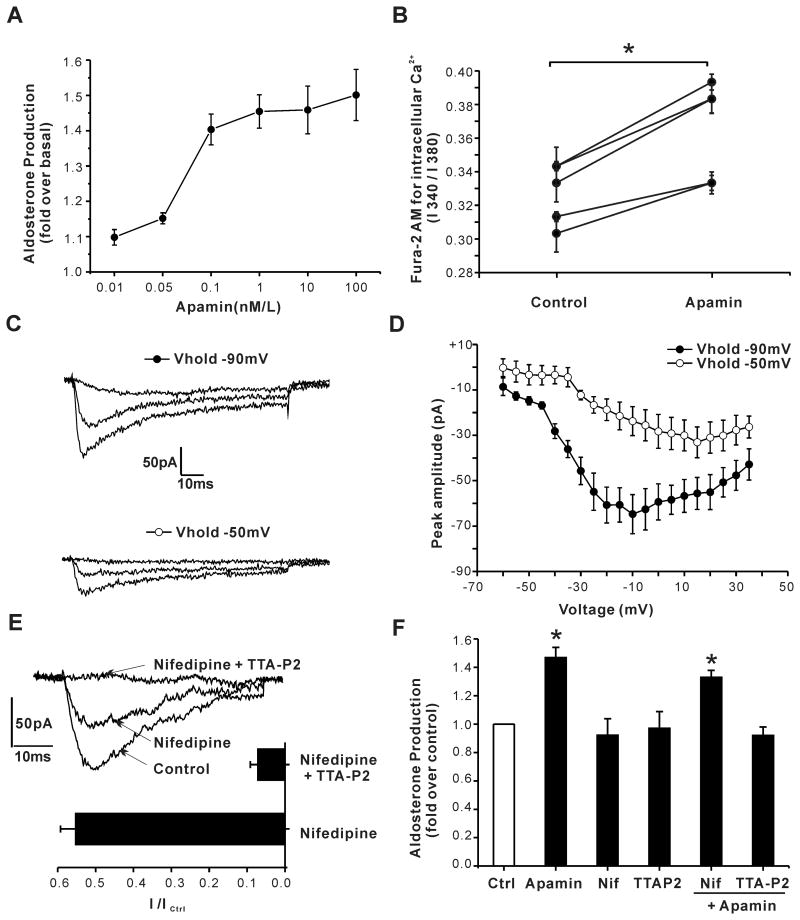

Apamin increases aldosterone secretion and depends on Ca2+ entry through T-type Ca2+ channels

To test for a role for SK channels in the regulation of basal aldosterone secretion, we used apamin to block SK currents. As shown in Fig. 2A, apamin increased aldosterone secretion from H295R cells in a dose-dependent manner (n=3-15, P < 0.05 compared with control by ANOVA). Production was stimulated to a maximal level of 50% with an EC50 of ∼0.08 n mol/L. Because aldosterone production critically depends on Ca2+, we tested whether block of SK channels by apamin was sufficient to increase intracellular Ca2+ levels in H295R cells. As shown in Fig. 2B, the basal level of intracellular Ca2+ was significantly and consistently increased following pretreatment with apamin (1 nmol/L, 24 hours).

Figure 2. Apamin increases aldosterone secretion mediating Ca2+ entry through T-type Ca2+ channels in H295R cells.

(A) Apamin increased aldosterone secretion dose-dependently. 12 h serum starved H295R cells were incubated in 0.1% FBS DMEM / F12 for 24 h with/without apamin at various concentrations. Data were expressed as fold- increase over control. P < 0.05 compared to control using a one-way ANOVA test. (n = 3∼12). (B) 24 h treatment with 1nmol/L apamin increased basal intracellular calcium concentration. Results are presented as mean ± S.E.M. of fluorescence excitation ratios. *, P < 0.05 compared to control using Students' t-test. (C, D) Ca2+ currents were evoked by 80-ms steps ( –60 to +35 mV in 5-mV increments) applied every 6 s from a VH of –90 or –50 mV. Shown are representative currents evoked by steps to –40, –10, or +10 mV from a VH of –90, or VH of –50 mV to reduce Cav3.x channel availability. Current-voltage relationship was constructed from peak currents (n = 7). (E) Effects of L-type Ca2+ channel inhibitor nifedipine (3 μmol/L) and T-type Ca2+ channel inhibitor TTA-P2(2 μmol/L) on Ca2+ currents. (F) TTA-P2 but not nifedipine precluded apamin-induced aldosterone production (n = 4, *, P < 0.05 compared to control by ANOVA).

Native ZG cells isolated from human, rodent or bovine adrenal glands express both low-voltage activated, T-type, and high voltage activated, L-type, Ca2+ channels in variable proportions6. To assess the relative contribution of T-type versus L-type Ca2+ currents in H295R cells used in these studies, we used patch clamp electrophysiology to characterize Ca2+ currents. We elicited test depolarizations in 5 mV-increments from -60 to +35 mV from a holding potential of -90 mV, to measure the combined activities of T-type and L-type Ca2+ channels, or from a holding potential of -50 mV (6 sec) to inactivate T-type Ca2+ channels and determine the activity of L-type Ca2+ channels in relative isolation. Notably, holding at – 50 mV, reduced maximal peak current by 49% and induced a rightward shift in the potential at which maximal peak current is recorded (from -10 mV to +15 mV) in agreement with the removal of a major component of low-voltage activated (T-type) channel current from the recorded current (Fig. 2C and 2D). We used nifedipine, a dihydropryidine L-type Ca2+ channel blocker22, or TTA-P2, a selective T-type Ca2+ channel blocker23 to assess the relative importance of each channel subtype to the apamin-induced stimulation of basal aldosterone production. From a holding potential of -90 mV, 50 ms step depolarizations to -20mV elicited a peak Ca2+ current that was inhibited maximally by 45.7% ± 4.0% when nifedpine (3μM/L) was applied alone. The addition of TTA-P2 (2μM/L) increased current inhibition to 94% ± 2.0% indicating nearly equal contributions of T and L current to the total elicited current (Fig. 2E). At these functionally effective concentrations neither nifedipine nor TTA-P2 inhibited basal aldosterone output. By contrast, TTA-P2, but not nifedipine, prevented the apamin-induced increase in aldosterone production in agreement with the privileged role previously reported for T-type Ca2+ channel currents in the control of aldosterone output from isolated ZG cells24 (Fig. 2F).

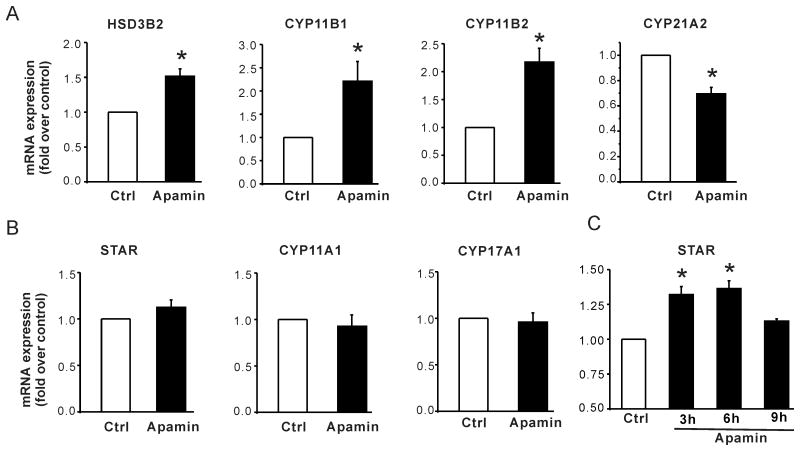

Effect of apamin on mRNA expression of steroid biosynthetic enzymes in H295R cells

To further investigate the mechanism by which apamin stimulates basal aldosterone production in H295R cells, we examined levels of mRNA for key steroidogenic enzymes and proteins that participate in aldosterone synthesis. After 24h treatment with 1 nmol/L apamin, mRNA expression of 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase-2 (HSD3B2), cytochrome P450, family 11,subfamily B, polypeptide 1 (CYP11B1) and aldosterone synthase (CYP11B2) were significantly increased 1.5-, 2.2- and 2.2- fold compared with untreated cells (Fig. 3A) whereas cytochrome P450, family 21, subfamily A, polypeptide 2 (CYP21A2) gene expression decreased by 0.7- fold (Fig. 3A). By contrast, apamin did not alter the mRNA for cytochrome P450, family 11, subfamily A, polypeptide 1 (CYP11A1), cytochrome P450, family 17, subfamily A, polypeptide 1 (CYP17A1) and steroidogenic acute regulatory protein (STAR) after 24h treatment (Fig.3B). Nevertheless, apamin did stimulate STAR mRNA expression in a time-dependent manner, with a maximal transient rise attained after approx. 6 h of incubation (Fig. 3C). A transient rise in STAR expression has been observed in H295R cells stimulated with very low density lipoprotein or angiotensin II25.

Figure 3. Effect of apamin on mRNA expression of the key proteins that control steroid biosynthesis: STAR, CYP11A1, HSD3B2, CYP21A2, CYP17A1, CYP11B1 and CYP11B2.

(A) Apamin increased HSD3B2, CYP11B1 and CYP11B2 but decreased CYP21A2 mRNA expression. 12 h serum starved H295R cells were incubated in DMEM/F12 with 0.1% FBS for 24 h with / without 1nmol/L apamin. Data are expressed as fold- change over control. *, P < 0.05 compared with control (n = 4∼7); (B) Apamin upregulated the expression of STAR at early time points. *, P < 0.05 compared with control (n = 3).

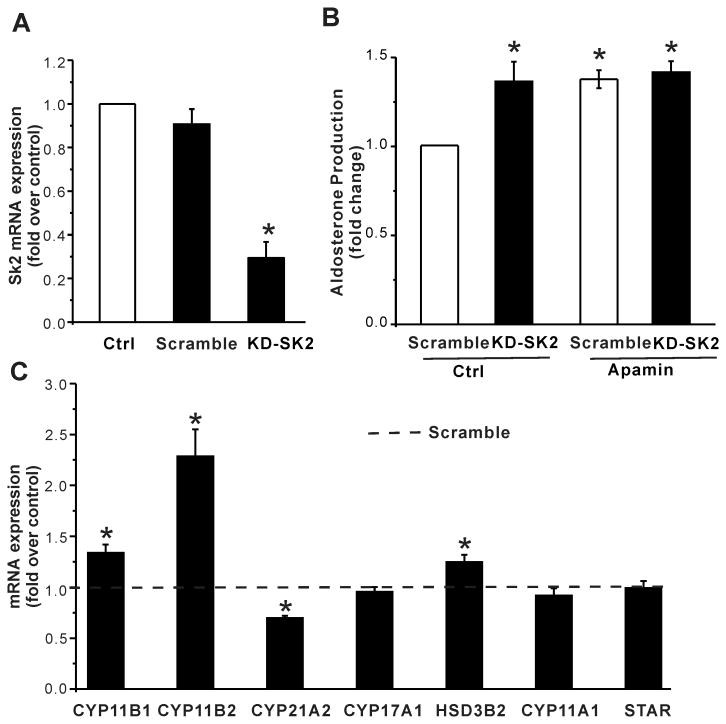

Effect of SK2 channel suppression on aldosterone production in H295R cells

Among SK channels, SK2 channels are the most sensitive to apamin (EC50: SK1 0.7–12.2 nM; SK2 27–140 pM; SK3 0.6–4 nM )26-31. Because stimulation of aldosterone production by apamin was near maximal at 0.1nmol/L (Fig.1A), we predicted that regulation by apamin was the result of inhibition of SK2 channel activity. Therefore, to independently evaluate the contribution of SK2 channels to the regulation of aldosterone production, we used lentivirus vectors to deliver shRNA targeted to effect post-translational silencing of the SK2 gene in H295R cells. 72 h after infection, H295R cells were serum deprived (0.1% serum, 12h) and fresh medium with or without apamin substituted (24h). As shown in Figure 4, shRNA-targeting SK2 channels, but not the scrambled control, reduced SK2 channel expression by 70% (Fig. 4A). This reduction was sufficient to increase basal aldosterone production by 35% (Fig. 4B) and importantly abrogated the apamin-induced increase in basal aldosterone output. The knockdown of SK2 channels also mimicked apamin-induced changes in mRNA expression, increasing that of CYP11B1, CYP11B2 and HSD3B2 (fold increase: CYP11B1, 1.3 ± 0.1, n = 5; CYP11B2, 2.3 ± 0.3, n = 4; HSD3B2, 1.24 ± 0.07, n = 4; P < 0.05 compared with scramble control), decreasing that of CYP21A2 while sparing that of CYP17A1, CYP11A1 or STAR (Fig. 4C). Taken together these data indicate that SK2 channel activity underlies the regulation of aldosterone production by apamin.

Figure 4. Effect of knockdown of SK2 channels on aldosterone secretion in H295R cells.

(A) The mRNA expression of SK2 channels was reduced by 70% in H295R cells transduced with shRNA-SK2 lentiviruses. (B) knockdown of SK2 channels increased basal aldosterone secretion, and abrogated apamin-induced increase. *, P < 0.05 compared with scramble control (n = 6). (C) knockdown of SK2 channels increased mRNA expression of CYP11B1 , CYP11B2 and HSD3B2, but decreased that of CYP21A2. *, P < 0.05 compared with scramble control (n = 4∼5).

Effect of apamin / 1-EBIO on Ang II- and K+ - induced aldosterone secretion

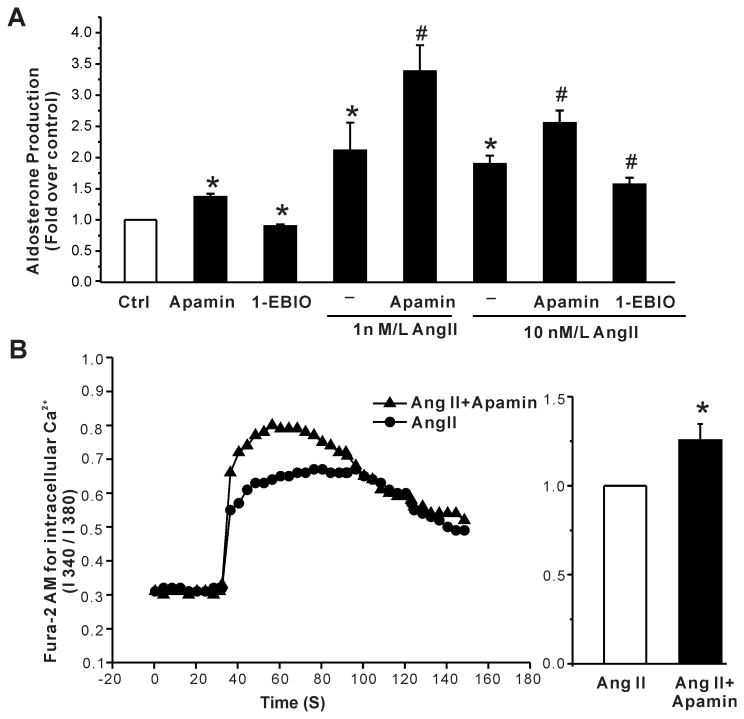

To assess the overall role of SK channels in aldosterone production, we tested for the apamin or 1-EBIO evoked modulation of AngII- and K+- induced aldosterone secretion. We used 1-EBIO, an activator of SK channels, to hyperpolarize and apamin to depolarize H295R cells and verified these predicted changes measuring membrane voltage in current clamp (voltage change: 1-EBIO, -9 ± 2 mV, n =8; apamin, +6 ± 1mV, n = 12). As observed for basal aldosterone output, 1 nmol/L apamin increased aldosterone production stimulated by low and high concentrations of Ang II (1 and 10 nmol/L; 1.6- fold and 1.34- fold respectively, Fig. 5A), whereas 100 μmol/L 1-EBIO suppressed Ang II-induced aldosterone secretion, in agreement with their opposing effects on membrane voltage. Commensurate with an increase in output, 24h treatment with apamin augmented the Ang II induced rise in intracellular Ca2+ (Fig. 5B) consistent with depolarization and the opening of voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels.

Figure 5. Effects of apamin and 1-EBIO on Ang II-stimulated aldosterone secretion in H295R cells.

(A) Apamin increased both basal and Ang II-stimulated aldosterone secretion, whereas 1-EBIO, an activator of SK channels, suppressed secretion. Data are presented as fold- change over control. *, P < 0.05 compared with control (n = 3). #, P < 0.05 compared with Ang II alone (n = 3). (B) 24h incubation with apamin increased Ang II-induced elevation of intracellular calcium (left). Baseline Ca2+ fluorescent signal was recorded for 30 sec; the Ang II -induced signal for 120 sec. Statistical analysis of Ang II-induced Ca2+ increase measured in control cells or apamin treated cells (right). Data expressed as fold increase over control cells. *, P < 0.05 compared with control (n = 4).

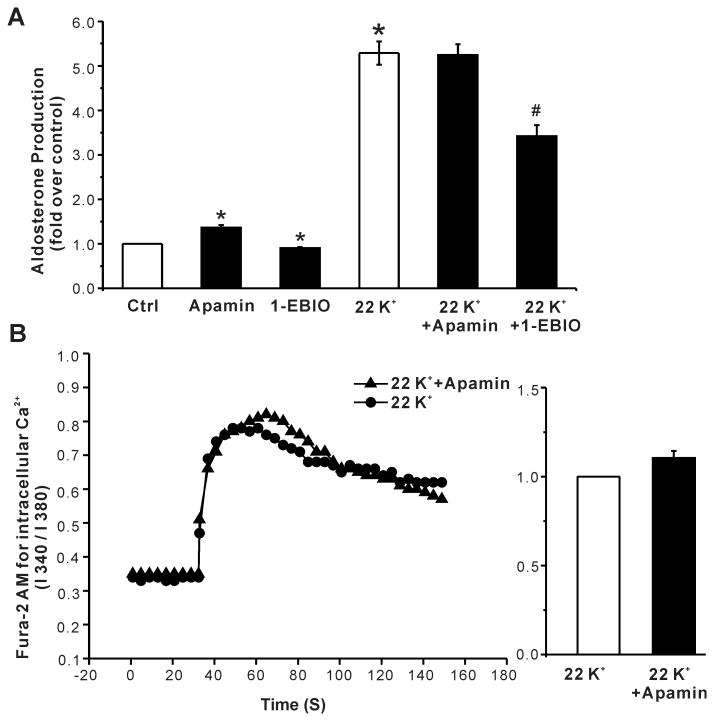

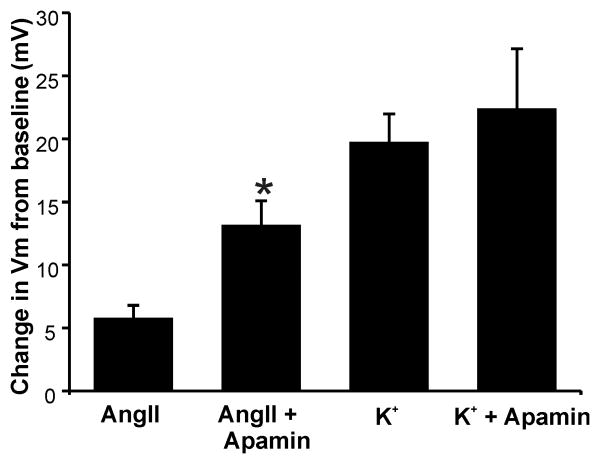

In vivo, aldosterone production is also modulated by extracellular K+ within the physiological range (2-5 mmol/L). Although H295R cells are responsive to extracellular K+, supra-physiologic concentrations are required to stimulate production. Raising extracellular K+ to 22 mmol/L increased aldosterone production 5.3-fold (Fig. 6A). However, unlike the more modest but maximal stimulation of production elicited by 10 nmol/L Ang II, aldosterone production evoked by 22 mmol/L K+ was not increased further by apamin but was reduced by 100 μmol/L 1-EBIO (fold increase: 22 mmol/L K+, 5.3 ± 0.3; K+ + 1-EBIO, 3.4 ± 0.2, P < 0.05 compared with 22 mmol/L K+ alone, n = 6, Fig. 6A). Consistent with a lack of effect of apamin on K+-induced aldosterone production, 1 nmol/L apamin failed to increase intracellular Ca2+ evoked by 22 mmol/L K+ (Fig. 6B). Notably, the failure to raise Ca2+ and stimulate aldosterone production in cells stimulated by 22 mmol/L K+ could be explained by the inability of apamin to further reduce membrane voltage in H295R cells that were already ∼20 mV depolarized by 22 mmol/L K+(Fig. 7).

Figure 6. Effects of apamin and 1-EBIO on high K+-stimulated aldosterone secretion in H295R cells.

(A) Apamin did not alter K+ -stimulated aldosterone secretion, whereas 1-EBIO suppressed it. *, P < 0.05 compared with control. #, P < 0.05 compared with high K+ alone. (B) 24h incubation with apamin did not alter high K+ -induced elevation of intracellular calcium (left). Baseline Ca2+ fluorescent signal was recorded for 30 s, the high K+-induced signal for 120 s. Statistical analysis of high K+ -induced intracellular Ca2+ level in control or apamin treated cells (right). Data expressed as fold- increase over control cells. P > 0.05 compared with control cells (n = 4).

Figure 7. Changes in membrane voltage (Vm) of H295R cells elicited by Ang II or K+ with/without Apamin.

Membrane voltage was determined in current-clamp. Plotted values are differences in Vm induced by 1 nmol/L apamin. Depolarization by apamin was additive to that of 10 nmol/L Ang II, but was subsumed by the voltage change induced by 22 mmol/L K+ (n = 5-7). *, P < 0.05 compared with Ang II alone.

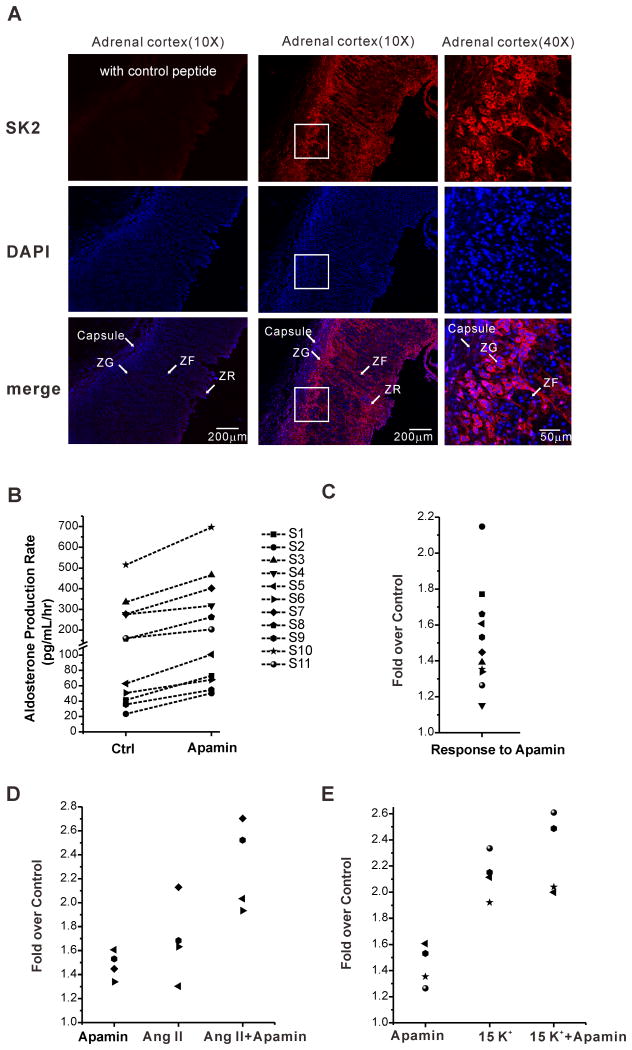

Effect of apamin on aldosterone production in ZG cells retained within a human adrenal slice

Finally, to assess the role of SK2 channels in the regulation of aldosterone production in native human glands, we tested first for their expression in human adrenal slices. As shown in Figure 8A, SK2 channels are highly expressed in the zona glomerulosa (ZG layer) of the human adrenal. Target antigen fluorescence was strong in the ZG layer, weak in the ZF and completely competed with antigenic peptide. Importantly, expressed SK2 channels were also functional as 1nm/L apamin significantly and consistently increased aldosterone secretion from adrenal tissue slices prepared from 11 individual patients (n=11, P < 0.05 compared with control Fig. 8B). Similar to modulation evoked by 1 nmol/L apamin in H295R cells, apamin further increased aldosterone production from human adrenal slices stimulated by 10nM/L Ang II (Ang II and Ang II + apamin; 1.7- fold and 2.3- fold respectively, P < 0.05, Fig. 8D), but failed to augment aldosterone production evoked by 15mmol/L K+ (P > 0.05, Fig. 8E).

Figure 8. SK2 channel expression in the zona glomerulosa of human adrenals and SK channel regulation of aldosterone.

(A) Representative examples of immunofluorescence images showing high expression of SK2 channels in zona glomerulosa of the human adrenal cortex. (B-E) 1 nmol/L apamin increased basal and 10 nmol/L Ang II induced aldosterone production, but failed to increase 15 mmol/L K+-stimulated aldosterone secretion from human adrenal slices. (S1-11 =samples from 11 individual patients)

Discussion

To date, SK channels are the only known target for apamin19, therefore inhibition of SK channel activity should account for the apamin-induced effects reported here. Accordingly, in this study we found that apamin increased aldosterone secretion from H295R cells, and that the genetic knockdown of SK2 channel expression by shRNA evoked a similar degree of steroid stimulation that was resistant to apamin modulation. Moreover both apamin block and silencing SK2 channel gene expression, evoked equivalent changes in the expression of steroidogenic enzymes and regulatory proteins, notably, increasing the mRNA expression of STAR and CYP11B2, that control the early and late rate-limiting step of aldosterone biosynthesis respectively. Together, these data argue that in human H295R cells, SK channels have a significant conductance in the basal state that negatively regulates or restrains the production of aldosterone.

SK channels are activated by submicromolar concentrations of internal Ca2+, and among SK channel subtypes, SK2 channels have the highest Ca2+ sensitivity. Such high Ca2+ sensitivity can allow for their activation by distal Ca2+ sources, such as intracellular Ca2+ stores 19. However, our data indicate that Ca2+ entry through voltage-gated plasma membrane Ca2+ channels of the T-subtype, provided the source of Ca2+ that activated SK channels, as apamin-evoked aldosterone production was block selectively by TTA-P2, the selective CaV3 Ca2+ channel blocker. Therefore, it is formally possible that SK channels are co-localized with CaV3.2 Ca2+ channels, the most abundant Cav3.0 subtype in ZG cells that accounts for ∼50% of Ca2+ current recorded in H295R cells in this study. SK channels are also functionally coupled to T-type Ca2+ channels in dopaminergic midbrain and cholinergic nucleus basalis neurons32, 33. Whether SK channels indeed form Ca2+ nano-domains with CaV3.2 channels in ZG cells, remains to be determined.

Because isolated ZG cells remain electrically quiescent, operating within a narrow voltage range of -85 to -40 mV, Cav3.2 channels have been found to be the primary Ca2+ entry pathway mediating Ang II / K+- stimulated aldosterone secretion in vitro34-38. However, as we have previously reported, ZG cells retained within an acutely prepared adrenal slice are electrically excitable, generating autonomous Vm oscillations. By providing the opportunity for recurrent channel activation, Vm oscillations allow an otherwise transiently activating Ca2+ channel (T-type) to transduce a substantial steady-state Ca2+ current that can support increased steroidogenesis for minutes to hours39. However, electrical excitability also provides the opportunity for high-voltage activated conductances to participate in the regulation of aldosterone production. Previous studies have shown that genetic deletion of either the pore-forming, KCNQ1, or regulatory, KCNE1, subunit of the large conductance, Ca2+- and voltage-activated potassium (BK) channel produces hyperaldosteronism in mice40, 41. BK channel mRNA expression is detected in both human adrenal samples and NCI-H295 cell line42, and the expression of SK channels in human adrenal cortex was detected by the Human Gene 1.0 ST Array13. The relative importance of SK versus BK channel types in the regulation of aldosterone production from the human adrenal cortex in vivo is as yet unexplored, but precedence for coordinated regulation of catecholamine secretion by these channel types is found in electrically excitable cells of adrenal medulla 43.

Ang II and K+ are the two most important physiological aldosterone secretagogues, and intracellular Ca2+ elevation and membrane depolarization are key features of their mechanisms of action. In this study, we found that SK channel activity regulated Ang II- but not K+-stimulated aldosterone secretion in H295R cells, as apamin augmented Ang II-stimulated aldosterone production, but failed to modulate aldosterone production evoked by high K+. Apamin also failed to augment the rise in intracellular Ca2+ evoked by high K+ suggesting a loss of capacity to alter membrane voltage during high K+-stimulation. Indeed, here we show that apamin functionally depolarized Ang II-stimulated H295R cells but was not able to alter membrane voltage in cells whose potential was clamped by 22 mmol/L K+. Nevertheless, these results do not rule out the possibility that SK channels contribute to the regulation of aldosterone production in vivo by physiological levels of K (2 to 5 mmol/L) that mosdestly shift the equilibrium potential for K+ and thus could allow the activity of SK2 channels to change ZG cell membrane voltage.

Previous studies suggested that the human adrenal cortex may express SK2 channels13,44. Here, we showed that SK2 channels are predominantly expressed in the ZG layer of the human adrenal cortex compared to that of the zona fasciculata, an expression pattern that is similar to that observed in rat adrenal45,46. Although apamin did not significantly increase K+-evoked aldosterone secretion from human adrenal slices stimulated by supra-physiologic levels of K+ (15 mmol/L), SK channels may still contribute to the regulation of production evoked by physiological levels of K+ in vivo. In this regard, it is noteworthy that the K+ concentration of the MEM Hanks used in our human adrenal steroidogenesis studies is ∼5.7 mmol/L. Therefore, the stimulation of basal rates of aldosterone production by apamin reported here predicts and supports the modulation of K+-elicited production of aldosterone by SK2 channels in vivo.

Perspective

Here, we show for the first time that SK channels negatively regulate aldosterone secretion in H295R cells and ZG cells within human adrenal slices. Blockage of SK channels increases mRNA expression of STAR and CYP11B2, that control respectively the early and late rate-limiting steps for aldosterone biosynthesis. By regulating membrane voltage, and evoked Ca2+ currents carried by T-type Ca2+ channels, SK channels modulate both basal and Ang II- stimulated aldosterone secretion in human adrenal glomerulosa cells. Together, our data support the possibility that SK channels contribute to the regulation of aldosterone secretion from native human adrenals. Whether genetic variation in the KCNN2 gene, like that of the KCNJ5 gene, also drives hyperaldosteronism in PA warrants further investigation.

Supplementary Material

Novelty and Significance.

What Is New?

This study demonstrates that SK channel activity negatively regulates both basal and Ang II-evoked aldosterone secretion from human adrenal cortical cells by alterations in membrane voltage and intracellular Ca2+ concentration. This regulation is orchestrated predominantly by SK2 channels activated selectively by Ca2+ entry through CaV3.x channels.

What Is Relevant?

Autonomous overproduction of aldosterone from ZG cells causes Primary hyperaldosteronism (PA). Recent clinical studies have highlighted the pathologic role of KCNJ5 potassium channel in PA. Identification of additional potassium channels responsible for the regulation of aldosterone secretion provides potentially new targets for diagnosis and treatment of PA.

Summary

Blockade of Small-conductance Ca2+-activated potassium channels by apamin or knockdown of Small-conductance Ca2+-activated potassium channel subtype 2 gene expression by shRNA increased basal aldosterone production from human adrenal cortical cells. By regulating membrane voltage, and evoked Ca2+ currents carried by T-type Ca2+ channels, Small-conductance Ca2+-activated potassium channels regulate both basal and angiotensin II - stimulated secretion of aldosterone.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding: This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC 31271240); the Specialized Research Fund for the Doctoral Program of Higher Education of China (20100071120022) and the Shanghai Leading Academic Discipline Project [B111] awarded to C.H, and the National Institutes of Health grants HL089717 and HL036977 awarded to P.Q.B.

Footnotes

Disclosures: None.

References

- 1.Aguilera G, Catt KJ. Participation of voltage-dependent calcium channels in the regulation of adrenal glomerulosa function by angiotensin ii and potassium. Endocrinology. 1986;118:112–118. doi: 10.1210/endo-118-1-112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Capponi AM, Lew PD, Jornot L, Vallotton MB. Correlation between cytosolic free ca2+ and aldosterone production in bovine adrenal glomerulosa cells. Evidence for a difference in the mode of action of angiotensin ii and potassium. J Biol Chem. 1984;259:8863–8869. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fakunding JL, Catt KJ. Dependence of aldosterone stimulation in adrenal glomerulosa cells on calcium uptake: Effects of lanthanum nd verapamil. Endocrinology. 1980;107:1345–1353. doi: 10.1210/endo-107-5-1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hausdorff WP, Aguilera G, Catt KJ. Selective enhancement of angiotensin ii- and potassium-stimulated aldosterone secretion by the calcium channel agonist bay k 8644. Endocrinology. 1986;118:869–874. doi: 10.1210/endo-118-2-869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kojima K, Kojima I, Rasmussen H. Dihydropyridine calcium agonist and antagonist effects on aldosterone secretion. Am J Physiol. 1984;247:E645–650. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1984.247.5.E645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spat A, Hunyady L. Control of aldosterone secretion: A model for convergence in cellular signaling pathways. Physiol Rev. 2004;84:489–539. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00030.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rossi GP. A comprehensive review of the clinical aspects of primary aldosteronism. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2011;7:485–495. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2011.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Young WF. Primary aldosteronism: Renaissance of a syndrome. Clin Endocrinol. 2007;66:607–618. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2007.02775.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Funder JW, Carey RM, Fardella C, Gomez-Sanchez CE, Mantero F, Stowasser M, Young WF, Jr, Montori VM, Endocrine S. Case detection, diagnosis, and treatment of patients with primary aldosteronism: An endocrine society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:3266–3281. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-0104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Milliez P, Girerd X, Plouin PF, Blacher J, Safar ME, Mourad JJ. Evidence for an increased rate of cardiovascular events in patients with primary aldosteronism. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45:1243–1248. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reincke M, Fischer E, Gerum S, et al. Observational study mortality in treated primary aldosteronism: The german conn's registry. Hypertension. 2012;60:618–624. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.112.197111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Savard S, Amar L, Plouin PF, Steichen O. Cardiovascular complications associated with primary aldosteronism: A controlled cross-sectional study. Hypertension. 2013;62:331–336. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.113.01060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Choi M, Scholl UI, Yue P, et al. K+ channel mutations in adrenal aldosterone-producing adenomas and hereditary hypertension. Science. 2011;331:768–772. doi: 10.1126/science.1198785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mulatero P, Tauber P, Zennaro MC, et al. Kcnj5 mutations in european families with nonglucocorticoid remediable familial hyperaldosteronism. Hypertension. 2012;59:235–240. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.183996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kuppusamy M, Caroccia B, Stindl J, Bandulik S, Lenzini L, Gioco F, Fishman V, Zanotti G, Gomez-Sanchez C, Bader M, Warth R, Rossi GP. A novel kcnj5-inst149 somatic mutation close to, but outside, the selectivity filter causes resistant hypertension by loss of selectivity for potassium. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99:E1765–1773. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-1927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Azizan EA, Lam BY, Newhouse SJ, Zhou J, Kuc RE, Clarke J, Happerfield L, Marker A, Hoffman GJ, Brown MJ. Microarray, qpcr, and kcnj5 sequencing of aldosterone-producing adenomas reveal differences in genotype and phenotype between zona glomerulosa- and zona fasciculata-like tumors. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:E819–829. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-2965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oki K, Plonczynski MW, Luis Lam M, Gomez-Sanchez EP, Gomez-Sanchez CE. Potassium channel mutant kcnj5 t158a expression in hac-15 cells increases aldosterone synthesis. Endocrinology. 2012;153:1774–1782. doi: 10.1210/en.2011-1733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wei AD, Gutman GA, Aldrich R, Chandy KG, Grissmer S, Wulff H. International union of pharmacology. Lii. Nomenclature and molecular relationships of calcium-activated potassium channels. Pharmacol Rev. 2005;57:463–472. doi: 10.1124/pr.57.4.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Adelman JP, Maylie J, Sah P. Small-conductance ca2+-activated k+ channels: Form and function. Annu Rev Physiol. 2012;74:245–269. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-020911-153336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu DD, Ren Z, Yang G, Zhao QR, Mei YA. Melatonin protects rat cerebellar granule cells against electromagnetic field-induced increases in na(+) currents through intracellular ca(2+) release. J Cell Mol Med. 2014;18:1060–1070. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.12250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wiznerowicz M, Trono D. Conditional suppression of cellular genes: Lentivirus vector-mediated drug-inducible rna interference. J Virol. 2003;77:8957–8961. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.16.8957-8961.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shen JB, Jiang B, Pappano AJ. Comparison of l-type calcium channel blockade by nifedipine and/or cadmium in guinea pig ventricular myocytes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2000;294:562–570. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Choe W, Messinger RB, Leach E, Eckle VS, Obradovic A, Salajegheh R, Jevtovic-Todorovic V, Todorovic SM. Tta-p2 is a potent and selective blocker of t-type calcium channels in rat sensory neurons and a novel antinociceptive agent. Mol Pharmacol. 2011;80:900–910. doi: 10.1124/mol.111.073205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rossier MF. T channels and steroid biosynthesis: In search of a link with mitochondria. Cell Calcium. 2006;40:155–164. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2006.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xing Y, Rainey WE, Apolzan JW, Francone OL, Harris RB, Bollag WB. Adrenal cell aldosterone production is stimulated by very-low-density lipoprotein (vldl) Endocrinology. 2012;153:721–731. doi: 10.1210/en.2011-1752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grunnet M, Jensen BS, Olesen SP, Klaerke DA. Apamin interacts with all subtypes of cloned small-conductance ca2+-activated k+ channels. Pflug Arch Eur J Phy. 2001;441:544–550. doi: 10.1007/s004240000447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grunnet M, Jespersen T, Angelo K, Frokjaer-Jensen C, Klaerke DA, Olesen SP, Jensen BS. Pharmacological modulation of sk3 channels. Neuropharmacology. 2001;40:879–887. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(01)00028-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Castle NA, London DO, Creech C, Fajloun Z, Stocker JW, Sabatier JM. Maurotoxin: A potent inhibitor of intermediate conductance ca2+-activated potassium channels. Mol Pharmacol. 2003;63:409–418. doi: 10.1124/mol.63.2.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Strobaek D, Jorgensen TD, Christophersen P, Ahring PK, Olesen SP. Pharmacological characterization of small-conductance ca(2+)-activated k(+) channels stably expressed in hek 293 cells. Br J Pharmacol. 2000;129:991–999. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shah M, Haylett DG. The pharmacology of hsk1 ca2+-activated k+ channels expressed in mammalian cell lines. Br J Pharmacol. 2000;129:627–630. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dale TJ, Cryan JE, Chen MX, Trezise DJ. Partial apamin sensitivity of human small conductance ca2+-activated k+ channels stably expressed in chinese hamster ovary cells. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2002;366:470–477. doi: 10.1007/s00210-002-0622-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wolfart J, Roeper J. Selective coupling of t-type calcium channels to sk potassium channels prevents intrinsic bursting in dopaminergic midbrain neurons. J Neurosci. 2002;22:3404–3413. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-09-03404.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Williams S, Serafin M, Muhlethaler M, Bernheim L. Distinct contributions of high- and low-voltage-activated calcium currents to afterhyperpolarizations in cholinergic nucleus basalis neurons of the guinea pig. J Neurosci. 1997;17:7307–7315. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-19-07307.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barrett PQ, Ertel EA, Smith MM, Nee JJ, Cohen CJ. Voltage-gated calcium currents have two opposing effects on the secretion of aldosterone. Am J Physiol. 1995;268:C985–992. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1995.268.4.C985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rossier MF, Burnay MM, Vallotton MB, Capponi AM. Distinct functions of t- and l-type calcium channels during activation of bovine adrenal glomerulosa cells. Endocrinology. 1996;137:4817–4826. doi: 10.1210/endo.137.11.8895352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rossier MF, Ertel EA, Vallotton MB, Capponi AM. Inhibitory action of mibefradil on calcium signaling and aldosterone synthesis in bovine adrenal glomerulosa cells. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1998;287:824–831. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lotshaw DP. Role of membrane depolarization and t-type ca2+ channels in angiotensin ii and k+ stimulated aldosterone secretion. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2001;175:157–171. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(01)00384-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Guagliardo NA, Yao J, Hu C, Barrett PQ. Minireview: Aldosterone biosynthesis: Electrically gated for our protection. Endocrinology. 2012;153:3579–3586. doi: 10.1210/en.2012-1339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hu C, Rusin CG, Tan Z, Guagliardo NA, Barrett PQ. Zona glomerulosa cells of the mouse adrenal cortex are intrinsic electrical oscillators. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:2046–2053. doi: 10.1172/JCI61996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Arrighi I, Bloch-Faure M, Grahammer F, Bleich M, Warth R, Mengual R, Drici MD, Barhanin J, Meneton P. Altered potassium balance and aldosterone secretion in a mouse model of human congenital long QT syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:8792–8797. doi: 10.1073/pnas.141233398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sausbier M, Arntz C, Bucurenciu I, et al. Elevated blood pressure linked to primary hyperaldosteronism and impaired vasodilation in bk channel-deficient mice. Circulation. 2005;112:60–68. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000156448.74296.FE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sarzani R, Pietrucci F, Francioni M, Salvi F, Letizia C, D'Erasmo E, Dessi Fulgheri P, Rappelli A. Expression of potassium channel isoforms mrna in normal human adrenals and aldosterone-secreting adenomas. J Endocrinol Invest. 2006;29:147–153. doi: 10.1007/BF03344088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vandael DH, Marcantoni A, Carbone E. Cav1.3 channels as key regulators of neuron-like firings and catecholamine release in chromaffin cells. Curr Mol Pharmacol. 2015;8:149–161. doi: 10.2174/1874467208666150507105443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chen MX, Gorman SA, Benson B, Singh K, Hieble JP, Michel MC, Tate SN, Trezise DJ. Small and intermediate conductance Ca(2+)-activated K+ channels confer distinctive patterns of distribution in human tissues and differential cellular localisation in the colon and corpus cavernosum. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2004;369:602–615. doi: 10.1007/s00210-004-0934-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Martinez-Arguelles DB, Campioli E, Lienhart C, Fan J, Culty M, Zirkin BR, Papadopoulos V. In utero exposure to the endocrine disruptor di-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate induces long-term changes in gene expression in the adult male adrenal gland. Endocrinology. 2014;155:1667–1678. doi: 10.1210/en.2013-1921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nishimoto K, Rigsby CS, Wang T, Mukai K, Gomez-Sanchez CE, Rainey WE, Seki T. Transcriptome analysis reveals differentially expressed transcripts in rat adrenal zona glomerulosa and zona fasciculata. Endocrinology. 2012;153:1755–1763. doi: 10.1210/en.2011-1915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.