Abstract

Objectives

The goals of this study were: (1) to evaluate patients’ knowledge regarding advance directives and completion rates of advance directives among gynecologic oncology patients and (2) to examine the association between death anxiety, disease symptom burden, and patient initiation of advance directives.

Methods

110 gynecologic cancer patients were surveyed regarding their knowledge and completion of advance directives. Patients also completed the MD Anderson Symptom Inventory (MDASI) scale and Templer’s Death Anxiety Scale (DAS). Descriptive statistics were utilized to examine characteristics of the sample. Fisher’s exact tests and 2-sample t-tests were utilized to examine associations between key variables.

Results

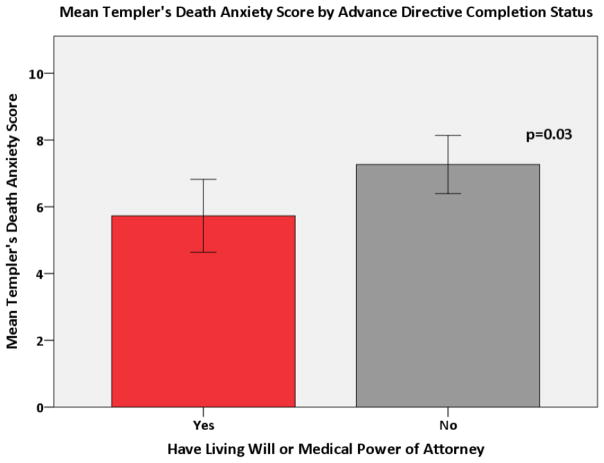

Most patients were white (76.4%) and had ovarian (46.4%) or uterine cancer (34.6%). Nearly half (47.0%) had recurrent disease. The majority of patients had heard about advance directives (75%). Only 49% had completed a living will or medical power of attorney. Older patients and those with a higher level of education were more likely to have completed an advance directive (p<0.01). Higher MDASI Interference Score (higher symptom burden) was associated with patients being less likely to have a living will or medical power of attorney (p=0.003). Higher DAS score (increased death anxiety) was associated with patients being less likely to have completed a living will or medical power of attorney (p=0.03).

Conclusion

Most patients were familiar with advance directives, but less than half had created these documents. Young age, lower level of education, disease-related interference with daily activities, and a higher level of death anxiety were associated with decreased rates of advance directive completion, indicating these may be barriers to advance care planning documentation. Young patients, less educated patients, patients with increased disease symptom burden, and patients with increased death anxiety should be targeted for advance care planning discussions as they may be less likely to engage in advance care planning.

Introduction

Advance care planning encompasses a wide spectrum of end-of-life care planning activities ranging from the creation of advance directive documents to patient discussion regarding end-of-life care goals with their family and medical providers. Advance directives include documents such as a living will, medical power of attorney, and a Do-Not-Resuscitate (DNR) order. These documents may be created without the assistance of a lawyer and most hospitals have templates that can assist patients with the creation of these documents. Advance care planning documents allow the patient to communicate desires related to treatment and care received at the end of life. This documentation represents a critical step in advance care planning. Creation of these documents allows the patient to clearly communicate their end-of-life wishes in the event that they are unable. Advance care planning encourages patients, their care-givers, and their providers to have an open dialogue regarding end-of-life care goals. In doing so, patients and providers may improve the likelihood that the patient receives end-of-life care that is consistent with the patient’s preferences (1).

In addition to being linked with patients’ wishes being more likely to be known and followed by their care-givers and their providers, engagement in advance care planning has been shown to be associated with patients being more likely to die in their place of preference (85% preferring their home) and having lower rates of death in the ICU (2, 3). Additionally, completion of advance directives and engagement in advance care planning has also been shown to be associated with fewer critical hospital interventions at the end of life (4). Finally, advance care planning has been shown to result in decreased hospital resource utilization (hospital admissions, procedures and ICU care) and increased hospice utilization at the end of life, thus resulting in improved healthcare resource allocation (5, 6).

Given the importance of advance care planning and its impact on receiving quality and value-consistent care at the end of life, current recommendations from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) and the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) recommend that providers encourage early advance care planning with their patients (7, 8). Despite the importance of advance care planning documentation, many terminally ill cancer patients are still not completing advance directives. One study found that only 27% of terminally ill cancer patients completed advance directives (9). The reason for low completion rates and communication regarding advance directives among cancer patients is unclear. Potential reasons for low completion rates may include limited provider initiation of these conversations or patient factors such as anxiety or difficulty discussing end-of-life care topics (10, 11).

Unfortunately, inadequate communication between patients and their providers regarding advance care planning may result in patients not receiving the type of care that they desire at the end of life (1). One study demonstrated this by showing that only 68% of terminally ill patients received end-of-life care consistent with their wishes, with 18% of patients who at baseline did not desire life-extending treatment at the end of life, ultimately receiving such treatment (1). Because life-extending treatment is associated with decreased quality of life, increased distress, and increased cost expenditure at the end of life, it is important that the patient’s desires regarding the level of care they receive are established via an advance directive or other communication prior to the patient being unable to make their own medical decisions (1, 5, 6, 12).

Little is known about gynecologic oncology patients’ knowledge, completion, and communication about advance care planning documents. It is important to understand this patient population because gynecologic oncology patients often have the same provider managing their surgical and chemotherapy care. Perhaps most importantly, this provider is often responsible for assisting the patient in transitioning to the end of life. The present study sought to examine gynecologic cancer patients’ knowledge of advance directives, their completion of advance directives, and the potential associations between death anxiety and symptom burden with patient initiation of advance directives.

Methods

One hundred and ten patients were surveyed regarding their knowledge and completion of advance care planning documents. Patients were eligible to participate in the IRB approved study if they: 1) had a gynecologic malignancy, 2) were currently receiving treatment or in active surveillance at our institution, 3) had an ECOG score of 2 or less, 4) were able to speak, read, and understand English, 5) were able to provide written informed consent. Patients meeting the eligibility criteria were recruited from the University of Texas MD Anderson Gynecologic Oncology Clinic in Houston, TX at their follow-up appointment. This study was nested in a prospective study to create and validate an instrument for assessing patient willingness to discuss end-of-life issues. The prospective study was powered for the creation and validation of the scale, with the focus being on having enough patients to complete an exploratory factor analysis and a confirmatory factor analysis for the instrument validation. Patients were purposively recruited to evenly represent women receiving treatment and those not. Participation was voluntary and without compensation. Patients completed a background questionnaire assessing age, race/ethnicity, marital status, education, religion, and occupation. Details regarding the patient’s cancer, current treatment, and presence of advance directives (living wills, and medical power of attorney documents) were obtained from patients’ medical records. Patients additionally completed the MD Anderson Symptom Inventory (MDASI) scale and Templer’s Death Anxiety Scale (DAS) (described below).

Questionnaires

MD Anderson Symptom Inventory (MDASI)

This validated 19-item, self-administered questionnaire, which assesses patient reported symptoms of their disease and treatment side-effects, was used to evaluate disease symptom burden. The MDASI evaluates how severe a patient’s symptoms have been within the last 24 hours prior to questionnaire administration. The MDASI has two subscales: Symptom Severity and Symptom Interference. The symptom severity subscale is composed of 13 items (or questions) that evaluate the severity of the following symptoms: pain, fatigue, nausea, disturbed sleep, emotional distress, shortness of breath, lack of appetite, drowsiness, dry mouth, sadness, vomiting, difficulty remembering, and numbness or tingling. The symptom interference subscale includes 6 items that evaluate general activity, mood, walking ability, normal work, relations with other people, and enjoyment of life. The interference score is used as a measure of overall symptom distress and evaluates how the patient’s symptoms are impacting their daily activities, mood, and relationships with others. The MDASI uses a numeric rating scale ranging from 0–10 with 0 meaning symptom is “not present” and 10 meaning symptom is “as bad as you can imagine.” An overall MDASI score can be calculated by using the average of the 19 items. A higher score indicates higher symptom burden. This scale has good internal consistency and reliability (Cronbach’s alphas= 0.85–0.91) (13, 14).

Templer’s Death Anxiety Scale (DAS)

This validated scale, which is composed of 15 true/false questions that assess an individual’s level of anxiety surrounding death, was used to assess patients’ death anxiety (15, 16). This scale has good test-retest reliability (0.83) and internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.76) (15, 16). A higher score indicates increased death anxiety.

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics were utilized to examine characteristics of the sample. Fisher’s exact tests and 2-sample t-tests were utilized to examine associations between having advance directives with symptom severity, symptom interference, symptom burden and death anxiety. General linear regression models were then created to adjust for potential covariates when examining the relationship between scale scores and advance directives. Additional multivariate logistic regression models were created to examine potential characteristics associated with (1) having heard of an advance directive and (2) having an advance directive. The covariates included in the initial models were age, race (white vs. non-white), partnership status, education (associate degree or higher vs. high school degree or lower), identification with a religion, cancer stage (Stage III or IV vs. Stage I or II), and treatment status (active vs. surveillance). Backward selection was used to keep those covariates in the model with p < 0.1. Advance directive measures were forced into model regardless of p-value. All tests were two-sided with statistical significance determined using p < 0.05.

Results

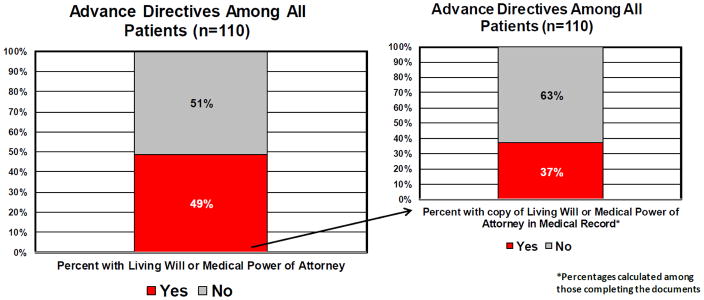

One hundred and ten patients were surveyed. The participation rate was 74%. The median age of the patients in the study was 61 years old. Most were white (76%), had ovarian (46%) or uterine (35%) cancer, and had advanced stage disease (53%). Table 1 shows the demographics and clinical characteristics of patients. Among all patient included in the study (n=110), most had heard about advance directives (75%, n=83). Of those who had heard about advance directives, 63% (n=52) were able to correctly define the term “advance directive.” Only 49% of those surveyed (n=54) had completed these documents. Of those 54 patients who said they had previously created a living will or medical power of attorney document, only 20 (37%) had a copy of the document in their chart (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Demographics

| N (%) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Age | N | 110 |

| Mean (SD) | 58.82 (12.06) | |

| Median | 61 | |

| Min - Max | 24–82 | |

|

| ||

| Race | White | 84 (76.36%) |

| African American | 4 (3.64%) | |

| Hispanic | 18 (16.36%) | |

| Asian | 3 (2.73%) | |

| Other | 1 (0.91%) | |

|

| ||

| Associate Degree or Higher | Elementary, HS, GED | 31 (28.18%) |

| Associate, Undergraduate, Graduate | 79 (71.82%) | |

|

| ||

| Cancer Site | Ovarian | 51 (46.36%) |

| Uterine | 38 (34.55%) | |

| Cervical | 17 (15.45%) | |

| Vulvar/Vaginal | 4 (3.64%) | |

|

| ||

| Stage | Not Staged | 12 (11.01%) |

| Stage I | 31 (28.44%) | |

| Stage II | 9 (8.26%) | |

| Stage III | 43 (39.45%) | |

| Stage IV | 14 (12.84%) | |

| Unknown/Missing | 1 | |

|

| ||

| Cancer Status | Surveillance | 55 (50.00%) |

| Primary Disease | 3 (2.73%) | |

| Recurrent Disease | 52 (47.00%) | |

|

| ||

| Current Treatment | Current Treatment | 55 (50.00%) |

| No Treatment or Hormonal Maintenance Therapy | 55 (50.00%) | |

|

| ||

| Heard about Advance Directives | Yes | 83 (75.45%) |

| No | 27 (24.77%) | |

|

| ||

| Heard about Hospice | Yes | 110 (100.00%) |

| No | 0 (0.00%) | |

|

| ||

| Able to correctly define the term “Advance Directive”* | Yes | 52 (62.65%) |

| No | 31 (37.35%) | |

Among those who had heard of advance directives

Figure 1.

Percentages of all patients completing advance directives and percent of advance directives in chart

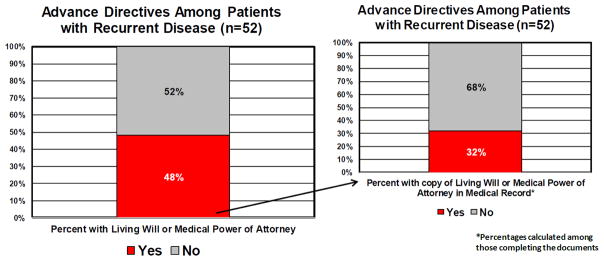

Of the 52 patients with recurrent disease who were undergoing active treatment for their recurrence, 38 patients (73.1%) knew about advance directives. However, only 25 patients (48.1%) with recurrent disease stated they had created a living will or a medical power of attorney document. Among those 25 patients with recurrent cancer who said they had previously created a living will or medical power of attorney, only 8 patients (32.0%) had a copy of the documents in their medical record (Figure 2). Treatment status was not significantly related to knowing about or having advance directives.

Figure 2.

Percentages of patients with recurrent disease completing advance directives and percent of advance directives in chart

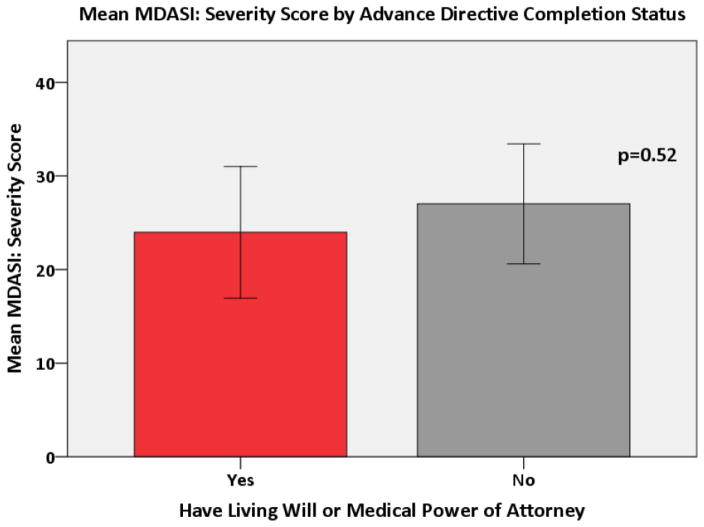

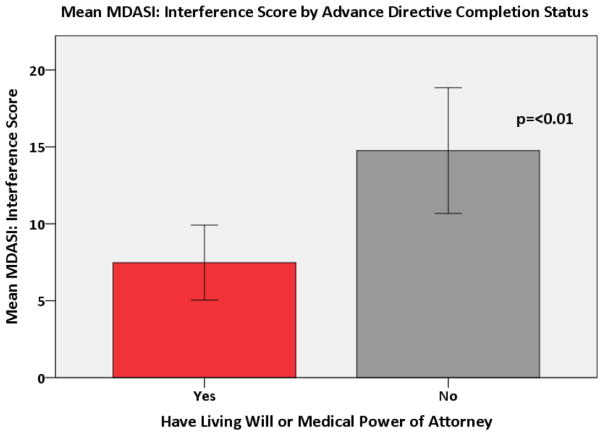

A multivariate logistic regression demonstrated that the odds of having heard about advance directives were 6.15 times higher in subjects with a higher education when compared to those with a high school degree or less (p<0.001). Both age and education were associated with having an advance directive. The odds of having an advance directive increased 11% for each one year increase in age (p<0.0001). The odds of having an advance directive were 4.08 times higher in subjects with more than a high school education when compared to those with a high school education or less (p<0.01). These associations remained even when testing for confounding. There was no association between the MDASI: Severity score and advance directive completion status (Figure 3). A higher MDASI: Interference Score was significantly associated with patients being less likely to have a living will or medical power of attorney (p=0.003) (Figure 4). This relationship held after adjusting for covariates in the multivariate model (p = 0.002). Finally, a higher DAS score was significantly associated with patients being less likely to have completed a living will or medical power of attorney (p=0.03) (Figure 5), even after adjusting for covariates (p = 0.03).

Figure 3.

Mean MDASI: Severity Score by Advance Directive Completion Status

Figure 4.

Mean MDASI: Interference Score by Advance Directive Completion status

Figure 5.

Mean Templer’s Death Anxiety Score by Advance Directive Completion Status

Discussion

Most patients in our cohort were familiar with advance directives, but less than half had created these documents. This is consistent with prior findings which indicate that approximately 27–50% of cancer patients complete advance directives (9, 17). Among patients with recurrent disease, who may be more in need of engaging in advance care planning, approximately half (48%) had an advance directive in place. Potential patient-level factors and barriers that might influence patients’ engagement in completion of advance directives included younger age, lower education level, disease-related interference with daily activities (MDASI) and a higher level of death anxiety (DAS). Increased patient experience of these factors was associated with lower odds of advance directive completion in our population. These findings indicate that there is room to improve patient engagement in advance care planning. Specifically, young patient age, lower patient education level, disease-related interference with daily activities, and increased death anxiety may be barriers to completion of advance care planning documentation and could be potential areas for intervention.

Barriers to advance care documentation extend beyond the actual creation of the documents themselves. Our study found that the majority of patients who had created an advance directive did not have a copy of the document within their medical record. Lack of advance care documentation in the medical record has been shown in other populations as well, indicating that this is a common problem (17). Inadequate documentation within the medical record is concerning because it may result in many patients undergoing aggressive care that is futile to prolonging their survival and associated with worse quality of life and is often not consistent with their values (6, 18–25). This issue of not receiving value-consistent care is common at the end of life, with prior studies demonstrating that only 55% of patients received care consistent with their desires (1). Advance care document completion and recording of that documentation within the medical record is imperative because discussion and documentation of desired care is associated with increased likelihood of receiving that care (1, 5). Providers must take steps to ensure timely entry of advance care planning documentation into the medical record.

Additionally, inadequate advance care planning documentations may place the responsibility of end-of-life care decisions on the patient’s family. Prior studies have shown that 29% of end-of-life care discussions among patients with gynecologic cancer had to be initiated with the patient’s family because the patient was unable to communicate with her medical team (26). These decisions place undue emotional distress on the family (2). Given the burden of leaving end-of-life care decision-making to family members, every effort must be made to accurately document the patient’s desires before she is unable to communicate with her family and medical team.

Our study also demonstrated that those patients with increased disease symptom burden and with increased death anxiety were less likely to complete advance directives. Prior research indicates that patients’ two largest self-reported barriers to lack of engagement in advance care planning includes perceiving advance care planning as irrelevant (84%; e.g., “I prefer to leave my health to fate”) and personal barriers (54%; e.g., “It makes me nervous or sad” and “I don’t want to think about death.”) (27). Both of these barriers point to the role that death anxiety and death avoidance might play in reducing patients’ odds of completing advance directives. This is consistent with results from our study, indicating that death anxiety (e.g., not wanting to think about one’s own death) is associated with lower odds of completing advance directives.

Little research has been conducted examining the association between symptom burden and completion of advance directives, but the results of this study present an alarming finding. Namely, that higher overall symptom distress as measured by the MDASI: Symptom Interference score (which represents patients for whom engagement in advance care planning may be more critical) was actually associated with lower odds of completing advance directives. Future research should examine the role that anxiety, specifically death anxiety, and symptom burden play as barriers to completion of advance directives.

Other patient factors such as age and education level impacted patient awareness and completion of advance directives. Within our study, more educated patients were more likely to have heard of advance directives. Additionally, older patients and those with a higher education level were more likely to have completed these documents. This finding corresponds with prior studies that suggest that older patients and more educated patients are more likely to have completed advance directives (28, 29). It is important to take into account the way that patient characteristics impact a patient’s likelihood of creating advance care documents so that providers can target populations with lower rates of document completion.

Our study represents one of the first to evaluate gynecologic oncology patients’ knowledge and completion of advance care planning documents. While our study does provide more insight into advance care planning documentation among gynecologic oncology patients, our study population was composed of highly educated patients with 72% of those surveyed stating that they had an associates, bachelors, or graduate degree. This may limit the generalizability of our findings regarding advance care documentation among gynecology oncology patients as those with higher education are more likely to have heard about and complete advance care documents (29).

Advance care planning documentation prior to the end of life has the potential to reduce the cost of care at the end of life and to improve patient quality of life at the end of life (1, 5). Findings from the present study indicate that there is room to improve advance care planning documentation among gynecologic oncology patients. Interventions such as advance care planning education programs have been shown to improve patient creation of advance care documents and should continue to be explored (30, 31). For these interventions to be most effective however, providers must identify and address barriers to advance care planning documentation in order to assist patients with achieving their end-of-life care goals. The present study highlights potential areas to target in future interventions. For instance, patients with recurrent cancer, young patients, less educated patients and those with increased disease symptom burden and death anxiety should be targeted for advance care planning discussions as they may be less likely to engage in advance care planning.

Highlights.

Most patients were familiar with advance directives

Less than half of those surveyed had created advance directives

Advance directive creation rates were impacted by patient characteristics

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health through MD Anderson Cancer Center’s Support Grant P30 CA016672 and T32 CA101642. Dr. Shen’s work on this project was supported by a cancer prevention fellowship from the National Cancer Institute (T32-CA009461).

Footnotes

The authors have no disclosures.

Conflicts of interest:

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Mack JW, Weeks JC, Wright AA, Block SD, Prigerson HG. End-of-life discussions, goal attainment, and distress at the end of life: predictors and outcomes of receipt of care consistent with preferences. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(7):1203–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.4672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Detering KM, Hancock AD, Reade MC, Silvester W. The impact of advance care planning on end of life care in elderly patients: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2010;340:c1345. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c1345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ratner E, Norlander L, McSteen K. Death at Home Following a Targeted Advance-Care Planning Process at Home: The Kitchen Table Discussion. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2001;49(6):778–81. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49155.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Richardson DK, Zive D, Daya M, Newgard CD. The impact of early do not resuscitate (DNR) orders on patient care and outcomes following resuscitation from out of hospital cardiac arrest. Resuscitation. 2013;84(4):483–7. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2012.08.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mack JW, Cronin A, Keating NL, Taback N, Huskamp HA, Malin JL, et al. Associations between end-of-life discussion characteristics and care received near death: a prospective cohort study. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(35):4387–95. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.43.6055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wright AA, Zhang B, Ray A, Mack JW, Trice E, Balboni T, et al. Associations between end-of-life discussions, patient mental health, medical care near death, and caregiver bereavement adjustment. JAMA. 2008;300(14):1665–73. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.14.1665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Available from: http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/f_guidelines.asp#supportive.

- 8.Smith TJ, Temin S, Alesi ER, Abernethy AP, Balboni TA, Basch EM, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology provisional clinical opinion: the integration of palliative care into standard oncology care. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(8):880–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.5161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kish SK, Martin CG, Price KJ. Advance directives in critically ill cancer patients. Critical Care Nursing Clinics of North America. 2000;12(3):373–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cherlin E, Fried T, Prigerson HG, Schulman-Green D, Johnson-Hurzeler R, Bradley EH. Communication between physicians and family caregivers about care at the end of life: when do discussions occur and what is said? J Palliat Med. 2005;8(6):1176–85. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2005.8.1176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dow LA, Matsuyama RK, Ramakrishnan V, Kuhn L, Lamont EB, Lyckholm L, et al. Paradoxes in advance care planning: the complex relationship of oncology patients, their physicians, and advance medical directives. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(2):299–304. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.6397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lopez-Acevedo M, Havrilesky LJ, Broadwater G, Kamal AH, Abernethy AP, Berchuck A, et al. Timing of end-of-life care discussion with performance on end-of-life quality indicators in ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2013.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cleeland CS, Mendoza TR, Wang XS, Chou C, Harle MT, Morrissey M, et al. Assessing symptom distress in cancer patients: the M.D. Anderson Symptom Inventory. Cancer. 2000;89(7):1634–46. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20001001)89:7<1634::aid-cncr29>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cleeland C. MD Anderson Symptom Inventory User’s Guide. 2010 Available from: http://www.mdanderson.org/education-and-research/departments-programs-and-labs/departments-and-divisions/symptom-research/symptom-assessment-tools/MDASI_userguide.pdf.

- 15.Robinson P, Wood K. In: Fear of death and physical illness: a personal construct approach. Epting F, Neimeyer R, editors. WA Hemisphere Publishing Company; 1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Templer DI. The construction and validation of a Death Anxiety Scale. J Gen Psychol. 1970;82(2d Half):165–77. doi: 10.1080/00221309.1970.9920634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Clark MA, Ott M, Rogers ML, Politi MC, Miller SC, Moynihan L, et al. Advance care planning as a shared endeavor: completion of ACP documents in a multidisciplinary cancer program. Psychooncology. 2015 doi: 10.1002/pon.4010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang B, Nilsson ME, Prigerson HG. Factors important to patients’ quality of life at the end of life. Archives of internal medicine. 2012;172(15):1133–42. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.2364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang B, Wright AA, Huskamp HA, Nilsson ME, Maciejewski ML, Earle CC, et al. Health care costs in the last week of life: associations with end-of-life conversations. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(5):480–8. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2008.587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mack JW, Weeks JC, Wright AA, Block SD, Prigerson HG. End-of-life discussions, goal attainment, and distress at the end of life: Predictors and outcomes of receipt of care consistent with preferences. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2010;28(7):1203–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.4672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Volandes AE, Ariza M, Abbo ED, Paasche-Orlow M. Overcoming educational barriers for advance care planning in Latinos with video images. Journal of palliative medicine. 2008;11(5):700–6. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2007.0172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blackhall LJ, Frank G, Murphy ST, Michel V, Palmer JM, Azen SP. Ethnicity and attitudes towards life sustaining technology. Social science & medicine. 1999;48(12):1779–89. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00077-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Davis A. Ethics and ethnicity: end-of-life decisions in four ethnic groups of cancer patients. Medicine and law. 1995;15(3):429–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Duffy SA, Jackson FC, Schim SM, Ronis DL, Fowler KE. Racial/Ethnic Preferences, Sex Preferences, and Perceived Discrimination Related to End-of-Life Care. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2006;54(1):150–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.00526.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gutheil IA, Heyman JC. “They Don’t Want to Hear Us” Hispanic Elders and Adult Children Speak About End-of-Life Planning. Journal of social work in end-of-life & palliative care. 2006;2(1):55–70. doi: 10.1300/J457v02n01_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zakhour M, LaBrant L, Rimel BJ, Walsh CS, Li AJ, Karlan BY, et al. Too much, too late: Aggressive measures and the timing of end of life care discussions in women with gynecologic malignancies. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;138(2):383–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2015.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schickedanz AD, Schillinger D, Landefeld CS, Knight SJ, Williams BA, Sudore RL. A clinical framework for improving the Advance Care Planning process: Start with patients’ self-identified barriers. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2009;57(1):31–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.02093.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hirschman KB, Abbott KM, Hanlon AL, Prvu Bettger J, Naylor MD. What factors are associated with having an advance directive among older adults who are new to long term care services? J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2012;13(1):82.e7–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2010.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ho GW, Skaggs L, Yenokyan G, Kellogg A, Johnson JA, Lee MC, et al. Patient and caregiver characteristics related to completion of advance directives in terminally ill patients. Palliat Support Care. 2016:1–8. doi: 10.1017/S147895151600016X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bravo G, Trottier L, Arcand M, Boire-Lavigne AM, Blanchette D, Dubois MF, et al. Promoting advance care planning among community-based older adults: A randomized controlled trial. Patient Educ Couns. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2016.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Volandes AE, Paasche-Orlow MK, Davis AD, Eubanks R, El-Jawahri A, Seitz R. Use of Video Decision Aids to Promote Advance Care Planning in Hilo, Hawai’i. J Gen Intern Med. 2016 doi: 10.1007/s11606-016-3730-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]