Abstract

Background

Endovenous ablation techniques and ultrasound‐guided foam sclerotherapy (UGFS) have largely replaced open surgery for treatment of great saphenous varicose veins. This was a randomized trial to compare the effect of surgery, endovenous laser ablation (EVLA) (with phlebectomies) and UGFS on quality of life and the occlusion rate of the great saphenous vein (GSV) 12 months after surgery.

Methods

Patients with symptomatic, uncomplicated varicose veins (CEAP class C2–C4) were examined at baseline, 1 month and 1 year. Before discharge and at 1 week, patients reported a pain score on a visual analogue scale. Preoperative and 1‐year assessments included duplex ultrasound imaging and the Aberdeen Varicose Vein Severity Score (AVVSS).

Results

The study included 214 patients: 65 had surgery, 73 had EVLA and 76 had UGFS. At 1 year, the GSV was occluded or absent in 59 (97 per cent) of 61 patients after surgery, 71 (97 per cent) of 73 after EVLA and 37 (51 per cent) of 72 after UGFS (P < 0·001). The AVVSS improved significantly in comparison with preoperative values in all groups, with no significant differences between them. Perioperative pain was significantly reduced and sick leave shorter after UGFS (mean 1 day) than after EVLA (8 days) and surgery (12 days).

Conclusion

In comparison with open surgery and EVLA, UGFS resulted in equivalent improvement in quality of life but significantly higher residual GSV reflux at 12‐month follow‐up.

Short abstract

Foam less effective

Introduction

Invasive treatment of superficial varicose veins and venous reflux improves quality of life compared with conservative treatment with compression stockings1. Conventional treatment of the incompetent great saphenous vein (GSV) has been surgical high ligation and stripping, combined with local phlebectomies. During the past decade, minimally invasive techniques, including ultrasound‐guided foam sclerotherapy (UGFS) and endovenous laser ablation (EVLA) have gained popularity in the treatment of varicose veins, and have largely replaced surgery. These new techniques are less invasive than the conventional surgery, and are associated with shorter postoperative recovery, owing to less pain, as well as fewer complications such as haematoma, groin infection and nerve damage2, 3, 4, 5. In recent studies comparing open surgery with UGFS and EVLA5, 6, 7, residual reflux was significantly more common after foam sclerotherapy compared with the other two treatments after 1 year. A recently published Cochrane systematic review8 comparing endovenous ablation (radiofrequency or laser) and UGFS versus open surgery suggested that EVLA and UGFS are at least as effective as surgery for great saphenous varicose veins in terms of patient satisfaction, but not in terms of anatomical success. Owing to variation in both the quality of the studies and reporting of the results, the quality of the evidence was graded only moderate.

The aim of the present randomized trial was to compare the efficacy of surgery, EVLA and UGFS in patients with primary symptomatic, uncomplicated great saphenous varicose veins (Clinical Etiologic Anatomic Pathophysiologic (CEAP) clinical grade C2–C4).

Methods

Consecutive patients with varicose veins were screened at two participating university hospitals in Finland between November 2007 and May 2010. Patients who fulfilled the inclusion criteria and were willing to participate were enrolled in a prospective randomized trial. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Helsinki University Central Hospital and Tampere University Hospital. All patients provided written informed consent before participating in the study, according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

The inclusion criteria were: unilateral symptomatic, uncomplicated varicose veins (CEAP clinical classification C2–C4), duplex ultrasound‐verified reflux in the GSV, mean diameter of the GSV in the thigh 5–10 mm, and age 20–70 years. Duplex ultrasound imaging was done in standing position, and reflux was measured after pneumatic compression of the calf. Incompetence was defined as a reflux of more than 0·5 s.

Exclusion criteria were: peripheral arterial disease, lymphoedema, BMI exceeding 40 kg/m2, pregnancy, allergy to the sclerosant or lidocaine, severe general illness, malignancy, previous deep vein thrombosis and coagulation disorder.

Randomization

The patients were randomized in outpatients to receive surgery, EVLA or UGFS. This was done using block randomization with sealed envelopes.

Procedures

Both the surgical and EVLA procedures were performed in the day surgery unit.

In the surgical procedure, the saphenofemoral junction (SFJ) was exposed in the groin and side branches were ligated back to the femoral vein. Retrograde invagination stripping of the GSV was done, usually down to below the knee. Tumescent solution (450 ml Ringer's solution with 50 ml 1 per cent lidocaine with adrenaline (epinephrine)) was injected into the tunnel of the stripped GSV. After stripping, hook phlebectomies were done through tiny incisions, using tumescent solution to minimize haematoma formation. The wound in the groin was closed with subcuticular sutures. Phlebectomy wounds were closed with surgical tape. Most patients had general anaesthesia. After the procedure, the leg was wrapped in bandages and covered with a class 2 graduated compression stocking. After 48 h, patients removed their bandages and then used the stocking alone during the day for up to 2 weeks. A prescription for paracetamol with, or without codeine, or ibuprofen was given on discharge with the instruction that the medication be used when necessary.

EVLA procedures were done under tumescent local anaesthesia (same solution as above) injected around the GSV under ultrasound guidance. A light sedative was administered before (diazepam) and during (alfentanil, propofol) the procedure. The laser ablation was carried out under duplex guidance. At the beginning of the study, a 980‐nm diode laser (Ceralas® D 980; Biolitec, Bonn, Germany) was used, but during the study this was replaced with a 1470‐nm radial laser (ELVes®; Biolitec). A pulsed mode, with a 1·5‐s impulse and 12 W of energy, was used routinely, with the aim of applying 70 J/cm GSV. The EVLA catheter tip was positioned 1·5–2 cm below the SFJ using ultrasound guidance. After the laser procedure, phlebectomies were done, as in the surgical procedure. No skin sutures were used. Thereafter, the protocol was the same as that after the surgical procedure.

UGFS was undertaken in outpatients by a vascular surgeon with an assisting nurse. Patients were examined by duplex ultrasound imaging before the treatment with the patient standing, and the cause of reflux was confirmed. During the treatment the patient remained supine. The GSV was cannulated under ultrasound guidance, usually at proximal thigh level and immediately below the knee. The sclerosant foam was prepared with a double‐syringe technique with a sclerosant to air ratio of 1 : 2. The sclerosants used were polidocanol 1 per cent (Aetoxysclerol®; Kreussler, Wiesbaden, Germany) and sodium tetradecyl sulphate (STS) 1 per cent and 3 per cent (Fibrovein™; STD Pharmaceutical Products, Hereford, UK). The injection of foam was monitored by ultrasound imaging. After treatment, a compression stocking was applied with the instruction to wear it continuously for 3 days, followed by daytime use for 11 days. At 1‐month follow‐up, a duplex ultrasound examination was done and, if any reflux was observed, a second treatment with foam was carried out. These patients were seen again 4 weeks after the second treatment, and the need for a possible third treatment was checked by duplex imaging.

Assessments

The primary outcome measures were: 1‐year occlusion (or absence) rate of GSV on routine duplex imaging, and changes in disease‐specific quality of life according to the Aberdeen Varicose Vein Severity Score (AVVSS)9. The diameter of the GSV 20 cm below the groin was also measured and compared with preoperative values. Secondary outcome measures were: perioperative pain measured using a visual analogue scale (VAS) from 0 (no pain) to 10 (worst possible, unbearable, excruciating pain) at the time of discharge and at 1 week after the procedure; duration of sick leave; and rate of complications such as haematoma, pigmentation, thrombophlebitis and paraesthesia.

Statistical analysis

Sample size calculations indicated that to detect a 20 per cent difference in occluded or absent GSV between the groups, with α = 0·05 and β = 0·8, 70 patients would be needed in each group.

Data were analysed according to intention to treat. The primary endpoint, occlusion or absence of GSV, was analysed in the overall study group and in three subgroups according to the size of the GSV in the mid‐thigh.

Continuous variables are reported as mean(s.d.) (range). Baseline and follow‐up variables were compared using the paired‐samples t test and repeated‐measures test. Statistical analysis was done using statistical software for Windows® (SPSS® version 19.0; IBM, Armonk, New York, USA).

Results

A total of 598 consecutive patients were screened between November 2007 and May 2010. Of these, 233 patients (233 legs) fulfilled the inclusion criteria and were willing to participate; they were randomized in the trial (Fig. 1). Nineteen randomized patients were excluded from the study before treatment. The most common reason was that the patient met an exclusion criterion that was not recognized at the time of randomization. Thus, the final study population comprised 214 patients: 65 in the surgery group, 73 in the EVLA group and 76 in the UGFS group. Owing to the operating surgeon's preference, five patients originally randomized to EVLA were treated with surgery but, because the analysis was made according to intention to treat, these patients were analysed in EVLA group. All 214 patients attended the 1‐month follow‐up, and 206 (96·3 per cent) the 1‐year follow‐up: 61 of 65 after surgery, all 73 patients who had EVLA and 72 of 76 who had UGFS.

Figure 1.

CONSORT diagram for the trial. EVLA, endovenous laser ablation; UGFS, ultrasound‐guided foam sclerotherapy

There were no significant differences in the basic demographics, CEAP clinical classification, AVVSS or GSV dimensions at baseline between the study groups (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographics and preoperative measurements

| Surgery (n = 65) | EVLA (n = 73) | UGFS (n = 76) | Total (n = 214) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years)* | 47·3(11·3) (27–75) | 47·0(13·4) (20–73) | 48·3(12·7) (23–74) | 47·6(12·4) (20–75) |

| Sex ratio (F : M) | 55 : 10 | 55 : 18 | 58 : 18 | 168 : 46 |

| BMI (kg/m2)* | 25·1(3·7) (19–37) | 25·2(3·6) (19–35) | 25·8(4·6) (20–42) | 25·4(4·0) (19–42) |

| Diameter of GSV (mm) | ||||

| At SFJ | 8·7(2·0) (5–14) | 8·5(2·2) (5–15) | 8·4(1·7) (5–13) | 8·5(2·0) (5–15) |

| Below groin | 6·6(1·3) (4–11) | 6·8(1·2) (4–10) | 6·7(1·2) (4–10) | 6·7(1·2) (4–11) |

| Mean | 6·2(1·1) (4–9) | 6·3(1·1) (4–8) | 6·7(1·1) (4–9) | 6·2(1·1) (4–9) |

| Baseline CEAP class | ||||

| C2 | 33 | 27 | 26 | 86 |

| C3 | 26 | 36 | 37 | 99 |

| C4 | 6 | 10 | 13 | 29 |

| Baseline AVVSS* | 30·2(6·3) (16–45) | 32·4(6·7) (18–51) | 31·7(7·6) (13–52) | 31·5(6·9) (13–52) |

Values are mean(s.d.) range. EVLA, endovenous laser ablation; UGFS, ultrasound‐guided foam sclerotherapy; GSV, great saphenous vein; SFJ, saphenofemoral junction; CEAP, Clinical Etiologic Anatomic Pathophysiologic; AVVSS, Aberdeen Varicose Vein Severity Score.

Perioperative results

The mean(s.d.) duration of treatment was 95(19) (range 62–155) min in the surgery group and 83(17) (range 50–139) min in the EVLA group (P < 0·001). Twenty‐six patients (34 per cent) in the UGFS group received two treatments; no patient required a third treatment. The sclerosants employed for the first treatment were: STS 3 per cent (64 patients), STS 1 per cent (6), polidocanol 3 per cent (4) and polidocanol 1 per cent (2). The mean volume of foam used in the GSV was 4·7(1·6) (range 2·0–9·0) ml. Some 33 per cent also had foam injected into varicose tributaries: mean volume 4·6 (range 2·0–12·0) ml. In the second treatment session, the mean volume of foam used in the GSV was 3·8 (2·0–10·0) ml.

Primary outcome measures

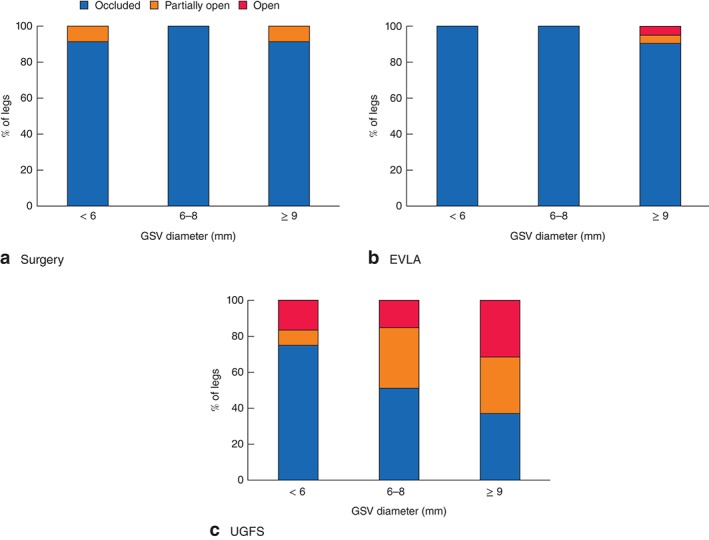

At 1 year, the GSV was completely occluded or absent in 59 (97 per cent) of 61 patients after surgery, 71 (97 per cent) of 73 after EVLA and 37 (51 per cent) of 72 after UGFS. The GSV was partially occluded in two patients (3 per cent), none (0 per cent) and 21 patients (29 per cent) in the respective groups. The difference between UGFS and the two other treatments was significant (P < 0·001). No patient in the surgery group and only two (3 per cent) in the EVLA group had a patent GSV after 1 year, compared with 14 (19 per cent) in the UGFS group. Of the two patients with a patent GSV in the EVLA group at 1 year, one had a tiny but patent GSV with no reflux and the other had asymptomatic reflux in a very narrow GSV. On duplex imaging at 1 year, reflux was seen in the below‐knee GSV in 13, 16 and 33 per cent of patients in the surgery, EVLA and UGFS groups respectively (P = 0·008 for UGFS versus other two procedures). Reflux in another unnamed thigh vein was present in 8, 10 and 12 per cent respectively (P = 0·471 between groups). When GSV patency rates were analysed according to size of the GSV before treatment, there was a clear correlation between larger diameter and GSV patency, but only in the UGFS group (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Patency of the great saphenous vein (GSV) at various diameters on duplex ultrasound imaging 1 year after a surgery, b endovenous laser ablation (EVLA) or c ultrasound‐guided foam sclerotherapy (UGFS)

At baseline, there were no significant differences in median AVVSS between the groups. At 1 year, median AVVSS was significantly improved in all groups and there were no significant differences between the groups (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Disease‐specific quality of life, measured by Aberdeen Varicose Vein Severity Score (AVVSS) at baseline and 1 year after surgery, endovenous laser ablation (EVLA) or ultrasound‐guided foam sclerotherapy (UGFS). Values are means with 95 per cent confidence intervals

After the 1‐year follow‐up visit, 16 patients had additional treatment: four patients (7 per cent) in the surgery group (UGFS for a thigh vein in 3 patients and ligation of a perforating vein in 1); one patient (1 per cent) after EVLA (foam sclerotherapy to a tributary at the ankle); and 11 patients (15 per cent) after UGFS (2 stripping of GSV, 5 EVLA of GSV and 4 repeat UGFS) (P = 0·009).

Secondary outcome measures

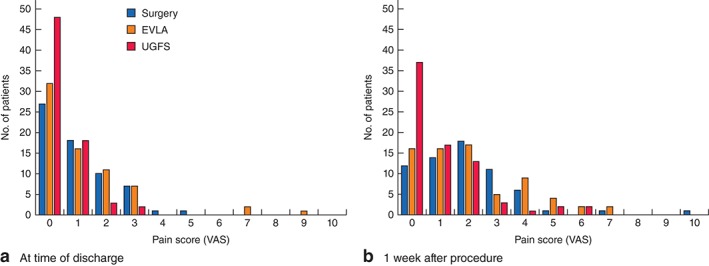

Pain after treatment was significantly reduced (lower VAS score) after UGFS in comparison with the surgery and EVLA groups, both at the time of discharge, and after 1 week (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Pain measured on a visual analogue scale (VAS; 1, none; 10, worst possible) a at the time of hospital discharge and b 1 week after surgery, endovenous laser ablation (EVLA) or ultrasound‐guided foam sclerotherapy (UGFS)

The mean duration of sick leave was 12(6) (range 0–33) days after surgery, 8(5) (range 0–29) days after EVLA and 1(3) (range 0–21) days after UGFS (P < 0·001 between UGFS and the 2 other groups).

There were no major complications related to the procedures. Three patients (4 per cent) in the EVLA group and three (5 per cent) in the surgery group had a superficial wound infection. All resolved with oral antibiotics; none of the patients needed treatment in hospital.

At the 1‐month follow‐up, 62 per cent of patients in the surgery group had a haematoma (defined as visible localized aggregate of extravasated blood) in the operated leg, compared with 42 per cent in the EVLA group and 20 per cent in the UGFS group (P = 0·001 between groups). Skin pigmentation was more common after UGFS (67 per cent) than after surgery and EVLA (5 and 4 per cent respectively; P < 0·001 for UGFS versus other 2 groups). Paraesthesia was rare in all groups (2, 3 and 1 per cent respectively). Palpable lumps in the veins under the skin were present at 1 month in 54 per cent of patients after surgery, 47 per cent after EVLA and 91 per cent after UGFS (P < 0·001 for UGFS versus other two groups).

Discussion

The present prospective randomized trial compared three interventions for unilateral primary great saphenous varicose veins. Reflux in the GSV was extremely rare at 1 year after surgical stripping or EVLA; however, after UGFS, reflux was seen in half of the patients, and the GSV was patent and refluxing in one of five. Despite these differences, disease‐specific quality of life was significantly better in all groups at 1 year compared with preoperative values, with no significant differences between the interventions.

Although recurrent/residual GSV reflux was seen in every other patient treated with UGFS, quality of life remained better than before surgery. One‐year follow‐up may be too early to show the consequences of recurrent reflux. The findings were similar in a multicentre study7 from the Netherlands that included 400 patients.

The largest trial comparing surgery, EVLA and UGFS in the treatment of GSV reflux included 798 patients, of whom 84 per cent completed 6 months of follow‐up9. In this series the complete success rate after 6 months was 78, 82 and 43 per cent respectively in the surgery, EVLA and UGFS groups. Similar to the present study, disease‐specific quality of life was significantly better in all three groups after 6 months than before intervention, but worse after UGFS. The same trend was seen in other studies5, 6, 7, 10.

The present study also examined the effect of GSV diameter on outcome. The occlusion rate after UGFS was clearly associated with GSV diameter: less than 40 per cent in GSVs of 9 mm or larger in mid‐thigh diameter, compared with 75 per cent in GSVs of less than 6 mm. This suggests that UGFS should not be recommended for veins larger than 6 mm in diameter.

There are some short‐term advantages from UGFS. In all three groups, patients reported increased pain after 1 week compared with immediately after treatment; the proportion of patients with no or minimal pain decreased during the first week. The majority of patients who had UGFS had no or minimal pain at 1 week. These findings contrast with those of Rasmussen and colleagues6, who reported that patients who had surgery or EVLA had the worst pain immediately after the procedure, which improved steadily over the first week. Some of the variation may be explained by the differences in the timing of the first measurement. In the present study, patients reported the VAS score immediately before discharge, when they may have had some remaining effects of perioperative analgesia. In the Danish study, the first measurement was completed on the first postoperative day.

Similarly, recovery from the intervention was fastest in patients who underwent UGFS. Recovery to daily work was longest after surgery; duration of sick leave was also greatest in the surgery group. These results accord with other studies2, 3, which reported sick leave of 1 week after EVLA and 2 weeks after surgery. Rasmussen and colleagues6 reported shorter sick leave of 7·6 days after surgery, possibly owing to the use of tumescent anaesthesia in surgical procedures.

The strength of the present study is that it was randomized, with excellent follow‐up, 96·3 per cent at 1 year. The main weakness is the relatively short follow‐up so far. The long‐term consequence of the high reflux rate after UGFS remains unclear. Another issue is that the foam used was more concentrated (air to sclerosant ratio 2 : 1) than in other studies. The impact of this is unknown as there are no randomized trials regarding the optimal foam recipe.

Patients with great saphenous varicose veins should understand that, although UGFS has some short‐term advantages in recovery, and equivalent quality of life after 1 year, longer follow‐up of the present patients may reveal that the higher rate of recurrent/residual GSV reflux at 1 year increases the long‐term risk of recurrent varicose veins.

Collaborators

Finnish Venous Study Collaborators: V. P. Suominen (Tampere University Hospital), P. Vikatmaa, P. Aho, M. Lepäntalo, K. Halmesmäki, S. Laukontaus, E. M. Weselius, S. Vuorisalo (Helsinki University Hospital).

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Presented in part to the Annual Meeting of the European Society for Vascular Surgery, Budapest, Hungary, September 2013

The copyright line for this article was changed on 9 September 2016 after original online publication.

References

- 1. Sell H, Vikatmaa P, Albäck A, Lepäntalo M, Malmivaara A, Mahmoud O et al Compression therapy versus surgery in the treatment of patients with varicose veins: a RCT. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2014; 47: 670–677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rautio T, Ohinmaa A, Perälä J, Ohtonen P, Heikinnen T, Wiik H. Endovenous obliteration versus conventional stripping operation in the treatment of primary varicose veins: a randomized controlled trial with comparison of the costs. J Vasc Surg 2002; 35: 958–965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lurie F, Creton D, Eklof B, Kabnick LS, Kistner RL, Pichot O et al Prospective randomized study of endovenous radiofrequency obliteration (closure procedure) versus ligation and stripping in selected patient population (EVOLVeS Study). J Vasc Surg 2003; 38: 207–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rasmussen LH, Bjoern L, Lawaetz M, Blemings A, Lawaetz B, Eklof B. Randomized trial comparing endovenous laser ablation of the great saphenous vein with high ligation and stripping in patients with varicose veins: short‐term results. J Vasc Surg 2007; 46: 308–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Biemans AA, Kockaert M, Akkersdijk GP, van den Bos RR, de Maeseneer MG, Cuypers P et al Comparing endovenous laser ablation, foam sclerotherapy, and conventional surgery for great saphenous varicose veins. J Vasc Surg 2013; 58: 727–734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rasmussen LH, Lawaetz M, Bjoern L, Vennits B, Blemings A, Eklof B. Randomized clinical trial comparing endovenous laser ablation, radiofrequency ablation, foam sclerotherapy and surgical stripping for great saphenous varicose veins. Br J Surg 2011; 98: 1079–1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. van der Velden SK, Biemans AA, De Maeseneer MG, Kockaert MA, Cuypers PW, Hollestein LM et al Five‐year results of a randomized clinical trial of conventional surgery, endovenous laser ablation and ultrasound‐guided foam sclerotherapy in patients with great saphenous varicose veins. Br J Surg 2015; 102: 1184–1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Nesbitt C, Bedenis R, Bhattacharya V, Stansby G. Endovenous ablation (radiofrequency and laser) and foam sclerotherapy versus open surgery for great saphenous vein varices. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014; (7)CD005624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Brittenden J, Cotton SC, Elders A, Ramsay CR, Norrie J, Burr J et al A randomized trial comparing treatments for varicose veins. N Engl J Med 2014; 371: 1218–1227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Shadid N, Ceulen R, Nelemans P, Dirksen C, Veraart J, Schurink GW et al Randomized clinical trial of ultrasound‐guided foam sclerotherapy versus surgery for the incompetent great saphenous vein. Br J Surg 2012; 99: 1062–1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]